Abstract

Background

Pea fiber (PF) is a potential fibrous supplement in swine production. The influence of dietary PF on microbial community in the colon of pigs remains largely unexplored. Methanogens in the hindgut of monogastric animals play important roles in degradation of dietary fibers and efficient removal of microbial metabolic end product H2. Understanding the impact of dietary PF on the structure of colonic methanogens may help understand the mechanisms of microbe-mediated physiological functions of PF. This study investigated the influence of PF on the diversity and quantity and/or activity of colonic methanongens of piglets and finishing pigs. Four archaeal 16S rRNA clone libraries were constructed for piglets and finishers fed with control (Piglet-C and Finisher-C) or PF diet (Piglet-P and Finisher-P).

Results

There were 195, 190, 194 and 196 clones obtained from the library Piglet-C, Piglet-P, Finisher-C and Finisher-P, respectively, with corresponding 12, 11, 11 and 16 OTUs (operational taxonomic units). Significant differences of Shannon Index among the four libraries were found (P < 0.05). Libshuff analysis showed that the archaeal community structure among the four libraries were significantly different (P < 0.0001). The predominant methanogens shifted from Methanobrevibacter to Methanobrevibacter and Methanomassiliicoccus-like genus as a result of dietary PF. Supplementation of PF significantly increased the copy numbers of mcrA and dsrA genes (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Alteration of methanogenic community structure may lead to functional transition from utilization of H2/CO2 to employment of both H2/CO2 and methanol/CO2. Quantification of three functional genes (mcrA, dsrA and fhs) of methanogens, sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and acetogens revealed that dietary PF also increased the activity of methanogens and SRB,probably associated with increased proportion of Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis-species. Further study is required to examine the interaction between specific methanogens and SRB during fermentation of dietary PF.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12866-016-0919-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pea fiber, Methanogen, Diversity, Colon, Pig

Background

Dietary fibers (DF) have been demonstrated to reduce incidence of intestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, colon cancer and diarrhea [1, 2]. DF that escape digestion in the small intestine pass largely intact into the colon where they function to increase viscosity and bulking of the fecal matter [3] and can be eventually degraded by colonic microbiota [4] in monogastric animals. With huge populations, gut microbes play a key role in digestion and absorption of nutrients and promotion of the host immune system [5]. As one of the 3 domains of microorganisms in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, methanogens mostly colonize the colon of monogastric animals and use hydrogen to reduce carbon dioxide, formate or acetate to methane [6], thus helping keep the efficiency of microbial fermentation in the hindgut. Changes of dietary components can have direct and rapid impact on microbial community of the gut [7] as an adaptative mechanism. Of the dietary components, DF is proven to have a major impact on the composition of intestinal microbiota [3]. Although methanogens have been recognized as an important group of microorganisms in microbial fermentation, few studies were carried out to investigate the interaction of DF and methanogens in the GI tract of monogastric animals.

Recently, researchers from Thailand investigated the quantity of methanogens in the feces of children from two different geographic regions using quantitative PCR [8]. The children from northeastern Thailand had significantly higher consumption frequency of meat (chicken and beef), a wide variety of carbohydrate sources including noodle, fermented rice, sweet potato, vegetables and fruits. In central Thailand, there was significant preference for rice, breakfast cereal and cow milk. Although there was a large difference of food structures between children from the two regions, no significant alteration on the quantity of fecal methanogens was observed. Another study on humans [9] showed that the cellulose-degrading bacterial community differed in methane- and non-methane-excreting individuals, and the structure of the cellulolytic community varied with the presence of methanogens in the gut. Volunteers who ingested type III resistant starch (RS) and reduced carbohydrate weight loss (WL) diet harbored higher proportion of colonic methanogens than those who ingested maintained and non-starch polysaccharides (NSPs, 27.7 g/d) diets [10]. In healthy participants with detectable archaea (>106 copies per gram of feces), principal component analysis (PCOA) identified a distinct archaeal factor with positive loadings of age, breath methane, TDF, TDF/1000 kcal, and number of log archaea 16S rRNA gene copies [11]. In addition, some enteral condition such as pH can also influence the quantity and activity of methanogens. It is also reported that a high FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligo-, Di- and Mono-saccharides And Polyols) load led to greater production of short chain fatty acids and subsequent acidification of the lumen, which might then inhibit the activity of methanogens [12]. Some early studies suggest that differences in diet do not affect methane production, because it is largely dependent on substrates of endogenous origin [13, 14]. Other studies show that exogenous substrates like lactulose in various doses [15, 16] and dietary pentoses [17] can significantly increase methane production.

These limited studies on humans mostly focused on the interaction between dietary components/environment and the quantity/activity (methane production) of methanogens. Whether there are similar results in other monogastric animals, such as pigs, remains unknown. Moreover, there is a dispute on whether or how the dietary factors impact on gut methanogens.

Pea fiber (PF) has been shown to improve human health by regulating glucose response, lipid metabolism, and intestinal frequency [18]. Our previous study demonstrated that supplementation of a soluble dietary fiber, yeast derived β-glucan, significantly increased the diversity of methanogens in the swine colonic digesta in vitro and showed a beneficial effect on the growth of methanogens, which might improve microbial fermentation efficiency in the hindgut of pigs [19]. As PF is one of the widely utilized dietary fibers, we hypothesize that ingestion of PF probably increases the diversity, quantity and/or activity of colonic methanogens both in piglets and finishers. Therefore, we investigated the influence of PF on the diversity and community of colonic methanogens in piglets and finishing pigs (finishers in brief) using 16S rRNA gene clone library analysis. Because methanogens, sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and acetogens are regarded as main potential competitors of H2, abundance of their functional genes, methyl-coenzyme M reductase (mcrA), dissimilatory sulfite reductase (dsrA) and formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase (fhs) was also examined to investigate the activity of the three H2 utilizing microbes.

Methods

Animal experiment and collection of samples

A total of 48 weaned pigs (Duroc × Landrace × Yorkshire, weaned at day 28) with an average initial body weight of 7.2 ± 0.5 kg were randomly allocated to 2 groups, PF-supplemented and control (without PF) groups as described in our previous study [18]. Pigs in the PF group were fed with diets containing 10% (30 d post-weaning), 20% (30–90 d post-weaning), or 30% (30–90 d post-weaning) of PF. The composition of diets and husbandry management has been described before [18].

At the end of the first (30 d post-weaning) and the third (160 d post-weaning) experimental period, twelve pigs in each group were sacrificed and the mid-colon tissues were removed immediately. Approximately 10 g digesta (divided into two sterilized 5-ml centrifuge tubes) from the mid-colon of each pig were immediately collected and stored at -80 °C for analysis of archaeal 16S rRNA clone library. Colonic digesta samples were classified according to their sources: Piglet-C and Finisher-C for samples from piglets and finishers in the control group, and Piglet-P and Finisher-P for samples from pigs in PF group.

DNA extraction, clone library construction and phylogenetic analysis

Nucleic acids for each sample were extracted from 0.5 g of wet colonic digesta using the bead-beating method described before [20]. The DNA samples were purified with a PCR Clean-Up system (Promega, Madison, USA) and stored at -20 °C for later analysis. PCR amplification for Archaeal 16S rRNA genes and construction of the clone libraries were carried out according to described methods [21]. A total of 200 transformed clones with correct sized inserts were selected and sequenced (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China).

For each clone library, chimeras of the sequences and assignment of 16S rRNA gene sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were analyzed with the software MOTHUR (ver 1.23.1) [22]. Coverage of each clone library was calculated according to the equation C = 1 - (n/N) [23]. GenBank’s Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) [24] and the phylogenetic software PHYLIP (ver 3.69) [24] was used to identify the nearest validly described neighbor of each sequence and construct the neighbor-joining tree, respectively.

Real-time PCR for abundance of methanogen, sulfate-reducing bacteria, acetogens, Methanobrevibacter genus, M. smithii and M. boviskoreani

Abundance of methanogen, SRB, acetogens, Methanobrevibacter, M. smithii and M. boviskoreani were quantified by real-time PCR on a BioRad CFX-96 real time system (BioRad, USA) using SYBR Green as the fluorescent dye. The copies of mcrA, dsrA and fhs genes (for methanogen, SRB and acetogens, respectively) were determined with primer sets qmcrA-F/qmcrA-R [25], Drs1 + -F/Dsr-R [26] and fhs1/FTHFS-r [27], respectively. Abundance of Methanobrevibacter [28], M. smithii [29] and M. boviskoreani [30] were determined with primer sets described previously. A total of 25 μl reaction mixture contained 12.5 μl of IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), 0.2 μM of primer sets and 5 μl of DNA template. The copies of each gene in each sample were determined in triplicate, and the mean values were calculated. Standard curve of each gene was generated by using the serial dilutions of purified PCR amplicon.

Statistical analysis

Copy numbers of mcrA, dsrA and fhs genes for group Piglet-C, Piglet-P, Finisher-C and Finisher-P were analyzed with One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) program using the statistical software SPSS 16.0. The numbers of Methanobrevibacter, M. smithii and M. boviskoreani between Piglet-C and Piglet-P, or Finisher-C and Finisher-P were compared with Paired Samples T-test. Results were expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences were considered as significant when P value is less than 0.05.

Results

The diversity of methanogens in the four clone libraries

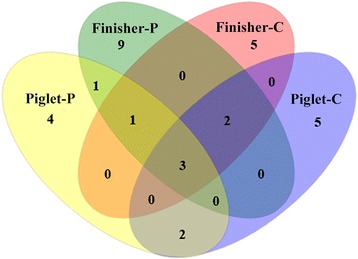

A total of 775 qualified sequences were obtained from the 800 cloned archaeal 16S rRNA amplicons and included 195, 190, 194 and 196 clones from libraries Piglet-C, Piglet-P, Finisher-C and Finisher-P, respectively. Sequence examination of these clones revealed a total of 32 OTUs (Table 1). The 195 sequences from group Piglet-C were classified into 44 different phylotypes (Additional file 1: Table S1) and 12 OTUs based on a 98% sequence identity criterion. The 190 sequences from Piglet-P library were assigned to 40 phylotypes and 11 OTUs (Additional file 1: Table S1). The 194 sequences from Finisher-C library were identified into 41 phylotypes and 11 OTUs. Those of the Finisher-P library were assigned to 43 phylotypes and 16 OTUs (Additional file 1: Table S1). There were five OTUs shared between libraries Piglet-C and Piglet-P, Piglet-C and Finisher-C, and Piglet-P and Finisher-P, respectively. Six OTUs were shared between libraries Finisher-C and Finisher-P (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Table 1.

Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of archaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences from colonic digesta of piglets and finishers

| OTU# | #Phylotype | #Sequence | Nearest Valid Taxona | % Sequence Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 28 | Methanobrevibacter smithii | 99.1 |

| 2 | 1 | 4 | Methanobrevibacter millerae | 98.7 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | Methanobrevibacter millerae | 98.1 |

| 4 | 2 | 7 | Methanobrevibacter millerae | 98.6 |

| 5 | 1 | 8 | Methanobrevibacter boviskoreani | 99.4 |

| 6 | 2 | 5 | Methanobrevibacter millerae | 98.2 |

| 7 | 1 | 27 | Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis | 86.6 |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter ruminantium | 96.9 |

| 9 | 1 | 2 | Methanobrevibacter boviskoreani | 99.7 |

| 10 | 2 | 11 | Methanobrevibacter millerae | 98.3 |

| 11 | 1 | 16 | Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis | 84.6 |

| 12 | 1 | 4 | Methanobrevibacter ruminantium | 96.4 |

| 13 | 1 | 3 | Methanobrevibacter ruminantium | 97.7 |

| 14 | 2 | 18 | Methanobrevibacter millerae/Methanobrevibacter smithii | 96.7 |

| 15 | 1 | 15 | Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis | 88.0 |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter millerae | 95.5 |

| 17 | 4 | 33 | Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis | 88.2 |

| 18 | 1 | 2 | Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis | 87.3 |

| 19 | 1 | 8 | Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis | 84.3 |

| 20 | 2 | 5 | Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis | 87.4 |

| 21 | 1 | 2 | Methanobrevibacter millerae | 96.1 |

| 22 | 1 | 5 | Methanobrevibacter gottschalkii | 97.9 |

| 23 | 1 | 4 | Methanobrevibacter gottschalkii | 97.5 |

| 24 | 1 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter gottschalkii | 97.6 |

| 25 | 5 | 33 | Methanobrevibacter millerae | 98.4 |

| 26 | 9 | 23 | Methanobrevibacter millerae | 97.8 |

| 27 | 4 | 14 | Methanobrevibacter gottschalkii | 98.3 |

| 28 | 10 | 59 | Methanobrevibacter ruminantium | 98.9 |

| 29 | 1 | 19 | Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis | 86.7 |

| 30 | 100 | 353 | Methanobrevibacter millerae/Methanobrevibacter gottschalkii | 98.6 |

| 31 | 6 | 52 | Methanobrevibacter olleyae/Methanobrevibacter millerae/Methanobrevibacter smithii | 96.1 |

| 32 | 1 | 9 | Methanobrevibacter gottschalkii | 98.3 |

| Totals | 168 | 775 |

aNearest valid taxon with the same name means the same strain

Fig. 1.

Venn diagram of the four clone libraries. Five OTUs were shared between group Piglet-C and Piglet-P, six between Finisher-C and Finisher-P, and five OTUs between Piglet-C and Finisher-C, or Piglet-P and Finisher-P

The coverage of the four libraries was from 98.95% to 99.49% (Table 2). The values of observed and estimated OTUs for each library were close to each other or with a variance less than 0.5 (Table 2). There were significant differences of the Shannon Index among the four libraries (P < 0.05). Libshuff analysis showed significant differences of methanogen community structure among the four libraries (P < 0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Coverage and Shannon Index calculated using MOTHUR1 for each methanogen 16S rRNA gene clone library

| Clone library | OTUs observed | CHAO1 OTU estimate | % OTU coverage2 | Shannon index ± 95% confidence limits | Libshuff analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piglet-C | 10 | 10 | 99.49 | 1.47 ± 0.15a | P < 0.0001 |

| Piglet-P | 11 | 11.5 | 98.95 | 1.53 ± 0.15b | P < 0.0001 |

| Finisher-C | 10 | 10 | 99.48 | 1.66 ± 0.13c | P < 0.0001 |

| Finisher-P | 15 | 15 | 99.49 | 2.08 ± 0.16d | P < 0.0001 |

1Schloss et al

2Good’s coverage (C) according to the equation C = 1 − (n/N), where n is the number of sequences represented by a single clone and N is the total

number of clones in the library

a,b,c,d There is significant difference between these values

The community structure of methanogens in the four clone libraries

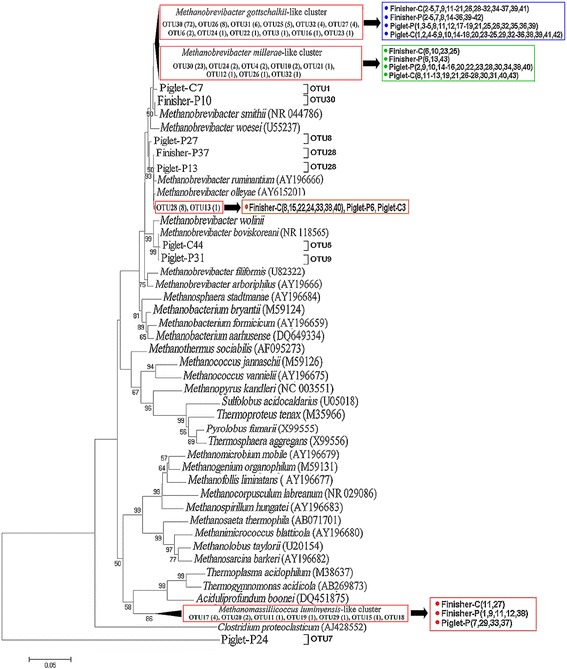

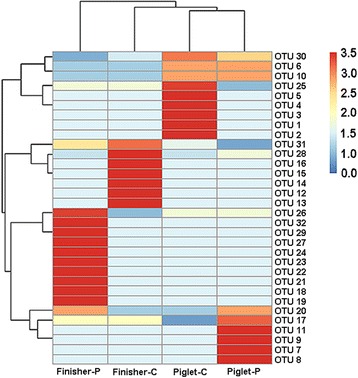

All sequences in the four libraries were identified to the phylum Euryarchaeota. Majority of the sequences (71%) in library Piglet-C were assigned to 8 different OTUs (OTU-2, OTU-3, OTU-4, OTU-6, OTU-10, OTU-25, OTU-26 and OTU-30) and closely related to species Methanobrevibacter millerae with sequence identities ranging from 97.2% to 98.7%. Twenty-eight sequences (14%) were assigned to OTU-1 and closely related to M. smithii (99.1%). OTU-25 with 18 sequences (9%) was closely related to M. gottschalkii with 98.4% identity, and OTU-5 with 8 sequences (4%), to M. boviskoreani with 99.4% identity. Only OTU-28 (2 sequences) was closely related to M. ruminantium (98.5%) (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Additional file 1: Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationship of archaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences retrieved from colonic samples of piglets and Finishers. Evolutionary distances were calculated using the Neighbor-Joining method. The tree was bootstrap resampled 1000 times

Fig. 3.

Heatmap distribution of OTUs of methanogens for all colonic samples. OTUs are arranged in rows and clustered on the vertical axis (y-axis). Groups are arranged vertically and are on the horizontal axis (x-axis). Clustering was done for each using Phylotrac’s heatmap option with Pearson correlations and complete lineage algorithms. Different colors indicate relative abundance of the taxons

About half of the sequences (48%) in library Piglet-P were assigned to 4 OTUs (OTU-6, OTU-10, OTU-26 and OTU-30) and closely related to species M. millerae with similarities from 97.1% to 98.6%. Sixty-nine sequences (36%) were assigned to 4 OTUs (OTU-7, OTU-11, OTU-17 and OTU-20) with lower similarities (from 84.6% to 88.1%) and related to Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis. Nineteen sequences (10%) were assigned to 2 OTUs (OTU-8 and OTU-28) and related to M. ruminantium with similarities from 96.9% to 98.9%. Eight sequences belonging to OTU-30 showed 97.9% to 98.3% relatedness to M. gottschalkii. Only two sequences assigned to OTU-9 were closely related to M. boviskoreani (99.7%)(Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Additional file 1: Table S1).

In library Finisher-C, nearly half of the sequences (47%) were assigned to 5 OTUs (OTU-14, OTU-16, OTU-25, OTU-26 and OTU-30) and related to M. millerae with similarities ranged from 95.5% to 98.4%. One fifth of the sequences (20%) assigned to 3 OTUs (OTU-12, OTU-13 and OTU-28) were affiliated to species M. ruminantium with similarities from 96.4% to 98.8%. Thirty-seven sequences (19%) belonging to OTU-14 and OTU-31 showed relatedness to M. smithii with lower identities (96.0% to 96.7%). Eighteen sequences (9%) were assigned to OTU-15 and OTU-17 and related to Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis with lower similarities from 88.0% to 88.2%. In addition, nine sequences were assigned to OTU-31 and related to Methanobrevibacter olleyae with 96.1% identity (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Additional file 1: Table S1).

There were 29% sequences in library Finisher-P assigned to 5 OTUs (OTU-21, OTU-25, OTU-26, OTU-30 and OTU-31) and related to M. millerae with identities ranging from 96.1% to 98.4%. Forty sequences (20%) were assigned also to 5 OTUs (OTU-17, OTU-18, OTU-19, OTU-20 and OTU-29) and related to Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis with low identities from 84.3% to 88.2%. Thirty-four sequences (17%) were assigned to 6 OTUs (OTU-22, OTU-23, OTU-24, OTU-27, OTU-30 and OTU-32) and closely (from 97.5% to 98.3%) related to M. gottschalkii. Additionally, thirty-eight, twenty-one and seven sequences were assigned and corresponded to OTU-30, OTU-31 and OTU-28, and related to M. smithii (98.6%), M. olleyae (98.7%) and M. ruminantium (96.1%), respectively (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Additional file 1: Table S1).

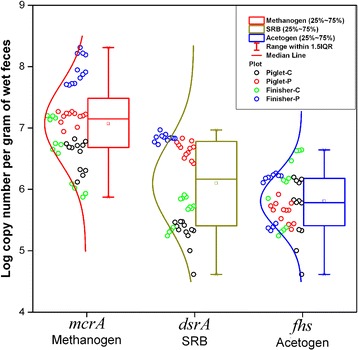

Abundance of total methanogens (mcrA), SRB (dsrA), acetogens (fhs) and specific methanogenic species in the colonic samples

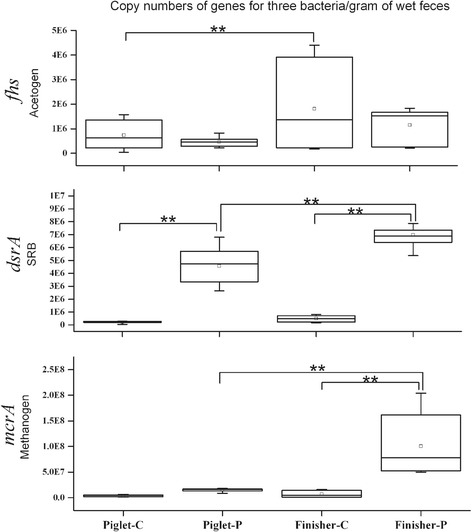

The inter quartile range (IQR) analysis showed that the qPCR data of mcrA, dsrA and fhs genes for samples from each group were relatively concentrated (Fig. 4). The copy number of the mcrA gene in samples from group Finisher-C and Piglet-P was significantly lower than Finisher-P (P < 0.01). Thst of the dsrA gene in samples from Piglet-C was significantly lower than Piglet-P (P < 0.01). Both Finisher-C and Piglet-P samples had lower copies of the dsrA gene than Finisher-P (P < 0.01). The copy number of the fhs gene in samples from group Piglet-C was significantly lower than Finisher-C (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

The interquartile range (IQR) diagram based on the qPCR data for the mcrA, dsrA and fhs genes

Fig. 5.

The box plot based on the qPCR data for the mcrA, dsrA and fhs genes. Significant differences (P < 0.01) are shown on the plot as “**”

Compared to group Piglet-C, significant increase was seen in abundance of the genus Methanobrevibacter (P < 0.01) and M. boviskoreani (P < 0.05) in samples from group Piglet-P, while marked reduction was observed in the number of M. smithii and the ratio of Methanobrevibacter to total methanogens (P < 0.01). In addition, the number of genus Methanobrevibacter and M. smithii was significantly (P < 0.01) higher in samples from Finisher-P than those from Finisher-C with significantly decreased ratio of Methanobrevibacter to total methanogens (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

The copy numbers of Methanobrevibacter, M. smithii and M. boviskoreani in samples from pigs of the four groups

| Methanogen group | Piglet-C | Piglet-P | P-Value | Finisher-C | Finisher-P | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanobrevibacter | 4.00 × 106 ± 2.43 × 106 | 9.43 × 106 ± 1.81 × 106 | 0.00 | 6.90 × 106 ± 5.55 × 106 | 1.00 × 108 ± 6.17 × 106 | 0.00 |

| M. smithii | 4.82 × 105 ± 2.51 × 105 | 2.58 × 104 ± 4.72 × 104 | 0.00 | 1.29 × 106 ± 1.46 × 106 | 1.88 × 107 ± 1.09 × 107 | 0.00 |

| M. boviskoreani | 1.47 × 105 ± 2.51 × 105 | 2.39 × 105 ± 1.60 × 105 | 0.03 | 1.93 × 104 ± 5.79 × 104 | 4.35 × 104 ± 1.44 × 105 | 0.61 |

| Methanobrevibacter% | 0.97 ± 0.03 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.87 ± 0.08 | 0.78 ± 0.05 | 0.02 |

The real-time PCR data are shown as Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD)

Discussion

The influence of DF to the diversity and activity of colonic methanogens is poorly understood. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report that dietary PF had extensive influence on the community structure of methanogens in the colon of pigs. The rarefaction curve (Additional file 1: Figure S1) and high coverage of the clone libraries (≥98.95%) indicated that the libraries were well sampled and the results based on sequencing analysis were representative. We clearly show that dietary PF increased the diversity of colonic methanogens in pigs. Similar result was observed in our previous in vitro study that yeast β-glucan significantly increased the archaeal diversity in fermented colonic digesta of pigs [19].

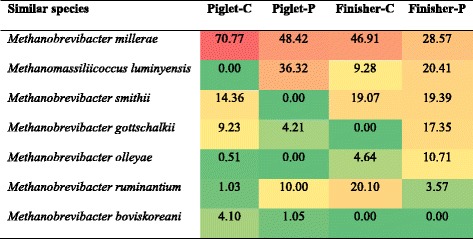

In the colon of piglets fed with basal diet, all archaeal sequences belonged to genus Methanobrevibacter. M. millerae and M. millerae-like species were the predominant methanogens (70.77% of the total sequences), followed by M. smithii, M. gottschalkii, M. boviskoreani, M. ruminantium and M. olleyae (Table 4). However, in the colonic digesta of piglets fed with PF diet, sequences belonging to M. millerae and M. gottschalkii were decreased with increased ratio of M. ruminantium associated sequences. Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis, which was not found in piglets receiving control diet, was the second predominant methanogen in the colon of piglets fed with PF diet. M. smithii and M. olleyae were not detected in PF-fed piglets (Table 4, Additional file 1: Figure S2). Interestingly, the change of methanogen species between control and PF-fed piglets was different to some degree from the finishers. M. millerae was the predominant species in the colon of finishers from both control and PF groups. Although Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis was found in finishers from both groups, its ratio in the colon of PF pigs was 11.13% higher than the control. M. gottschalkii was found only in PF-fed pigs, and M. boviskoreani was not detected from both groups (Table 4). Unlike piglets, both M. smithii and M. olleyae were increased in PF-fed finishers (Table 4, Additional file 1: Figure S2). A few studies reported that Methanobrevibacter was the main methaongen genus in the hindgut of humans and most monogastric animals [5, 31–33], in which Methanobrevibacter and M. smithii were predominant [31, 34]. Our study also revealed predominance of Methanobrevibacter, but not M. smithii, in the colon of pigs.

Table 4.

The proportion of most similar species in the four clone libraries (%)

The background color of each cell indicates relative abundance of each phylum with red and green indicating highest and lowest values

Methanogens belonging to the genus Methanobrevibacter, such as M. millerae, M. olleyae and M. boviskoreani, can utilize the end products of bacterial fermentation in the hindgut to produce methane from H2/CO2 or from formate plus CO2 [35]. While Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis, a newly isolated methanogen from human feces, produces methane by reducing methanol with hydrogen as the electron donor, it can not produce methane when hydrogen or methanol is the sole energy source [36]. Predominance of Methanobrevibacter in pigs from control group suggests that in the hindgut of these pigs, the methanogen species probably has preference to using H2 or formate and CO2 as substrates. The fact that dietary PF decreased the ratio of Methanobrevibacter to total methanogens (shown by qPCR) indicaties a relative increase of other methanogen genera. Predominance of Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis-like species in the PF-fed pigs suggests that the available substrates for methanogens in the colon of these pigs might become more diverse and shift from H2/CO2 and formate/CO2 to only menthanol/CO2. All these results indicate that PF supplementation in the diet can change the methanogen community structure in the colon of pig and render the methanogens more adaptable to different substrates for more efficient microbial fermentation, an indication on the response of methanogen community to dietary fiber in the hindgut of monogastric animal. The underlying mechanisms require further studies.

This study also considered the time effect of dietary PF to colonic methanogen community structure. In the colon of piglets at 30-d or finishers at 160-d old fed with control diet, Methanobrevibacter had absolute predominance. In PF-fed pigs, Methanobrevibacter was partially replaced by Methanomassiliicoccus-like genus at both age groups. Nevertheless, the proportion of Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis-like species was higher in piglets (36.32%) than in finishers (20.41%) fed with PF-containing diet (Table 4). These findings suggest that dietary PF probably favors the presence of Methanomassiliicoccus-like genus in piglets and finishers. This change in the methanogen community may be involved in the transition of their functions. Only one study found that the archaeal population shifted during weaning and M. boviskoreani replaced M. smithii, as shown by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) of mcrA gene [30]. However, we found a shift with decrease of M. boviskoreani and increase of M. smithii from piglets to finishers when fed on basal diet. In the PF group, M. boviskoreani was even not detected in finishers, while M. smithii increased from null to 19.39%. We had no explanation for this shift.

Archaeal sequences that are closely related to M. smithii, M. gottschalkii, M. millerae or M. thaurei are referred to as the smithii-gottschalkii-millerae-thaurei (SGMT) clade and those related to M. ruminantium and M. olleyae, as the ruminantium-olleyae (RO) clade. Distribution of SGMT and RO may vary with animal species and diets [37]. There were limited studies that focused mainly on the distribution of SGMT and RO in different ruminants [37, 38]. This study shows that SGMT is the predominant clade in the colon of all pigs. Compared with the control animals, the ratio of SGMT was markedly decreased (-41.73%) with increased RO clade in the colon of PF-fed piglets, while there was no apparent change of SGMT (-0.67%) and a decrease of RO in the colon of PF-fed finishers (Table 5, Additional file 1: Figure S3). During growth of the pigs in the control group, the SGMT clade was decrease relative to the change of RO. Supplementation of PF increased both SGMT and RO clades in the colon of finishers. Further study is needed to find out whether there is functional relationship between methanogens and their distribution of SGMT and RO clades.

Table 5.

The proportion of most closely related methanogenic clades in the four clone libraries (%)

The background color of each cell indicates relative abundance of each phylum with red and green indicating highest and lowest values

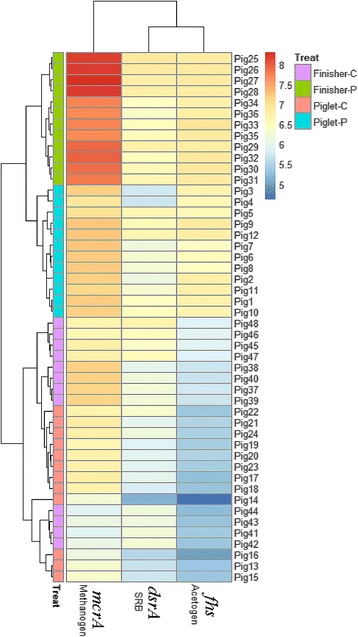

Accumulation of the end metabolic products, such as H2, CO2 and methanol, produced by colonic bacteria of monogastric animals can influence the fermentation efficiency of gut microbes [39]. Methanogens, SRB and acetogens are recognized as three important hydrogenotrophic microbes to assure fermentation efficiency through utilization of the end products [40–42]. There is competition among these hydrogenotrophic microbes [43]. Three unifying group specific genes, mcrA, dsrAB and fhs, are regarded as important functional genes which encode key enzymes involved in H2 consumption, namely, methyl-coenzyme M reductase, dissimilatory sulfite reductase, and formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase for methanogens, SRB and acetogens, respectively [44]. Thus, the quantity of these functional genes can reflect the activity of three hydrogenotrophic microbes. This study shows that dietary PF increased the activity of SRB in piglets and enhanced (Additional file 1: Table S2, Fig. 6) the activity of both methanogens and SRB in finishers. Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis-like species, the main methane producer using only methanol and H2, occupied a large proportion of methanogens in the colon of PF-fed pigs. Methanol is of particular interest as electron donor because it is readily available and cost effective [43, 45]. The fate of methanol in anaerobic reactors is determined by the outcome of direct competition between methanogens, SRB and homoacetogens [46]. SRB are the most efficient hydrogenotrophs when sulfate is used as the electron acceptor. Under pure culture conditions, the H2 threshold (lowest concentration of H2 that can be used) of SRB is significantly lower than the average threshold of acetogens and methanogens [47]. Therefore, our results further indicate that alteration of dietary components, such as PF supplementation, impacted the end products of colonic bacteria, which in turn leads to competition of methanogens and SRB. Surprisingly, the activity of acetogens increased from piglets to finishers in control group, indicating that the increased activities of methanogens and SRB are more important than acetogens for degradation of dietary PF.

Fig. 6.

Heatmap distribution of copy numbers of mcrA, dsrA and fhs genes for all colonic samples based on qPCR data. Samples (mcrA, dsrA and fhs genes) are arranged in rows and clustered on the vertical axis (y-axis). Gene copies are arranged vertically and are on the horizontal axis (x-axis). Clustering was done for each using Phylotrac’s heatmap option with Pearson correlations and complete lineage algorithms. Different colors indicate relative abundance of the taxons. Different colors showed on the left side of the diagram indicate the four groups (Piglet-C, Piglet-P, Finisher-C and Finisher-P)

Conclusions

Dietary PF increased the diversity of colonic methanogen community structure of pigs with a shift from Methanobrevibacter to Methanobrevibacter and Methanomassiliicoccus-like genus. This alteration may probably lead to functional transition, that is, utilization from H2/CO2 to both H2/CO2 and methanol/CO2. Moreover, dietary PF also increased the activity of methanogens and SRB, probably associated with increased proportion of Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis-species. Further study on the interaction between methanogenic and SRB species during fermentation of dietary PF is needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Weihuan Fang at Zhejiang University for his help on revision of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 31301987), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant number 2013 M542286 and 2015 T80986).

Availability of data and materials

The nucleotide sequences for the four clone libraries reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KU 362290 to KU362457.

Authors’ contributions

Yu-heng Luo conducted the research and wrote the paper, Hong Chen conducted the animal trial, Bing Yu, Jun He, Ping Zheng, Xiangbing Mao and Gang Tian helped conduct the animal trial and sample collection, Jie Yu, Zhiqing Huang, Junqiuluo and Dai-wen Chen designed the study. Daiwen Chen had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

All experimental procedures and animal care were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University, and all animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University under permit number DKY-B20131704.

Abbreviations

- DF

Dietary fibers

- dsrA

Dissimilatory sulfite reductase

- fhs

Formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase

- FODMAPs

Fermentable Oligo- Di- and Mono-saccharides And Polyols

- mcrA

methyl-coenzyme M reductase

- OTUs

Operational taxonomic units

- PF

Pea fiber

- SRB

Sulfate-reducing bacteria

Additional file

Supporting Data. (DOCX 159 kb)

Contributor Information

Yuheng Luo, Email: luoluo212@126.com.

Hong Chen, Email: calm945@yahoo.com.cn.

Bing Yu, Email: 617670847@qq.com.

Jun He, Email: 14003317@qq.com.

Ping Zheng, Email: zpind05@163.com.

Xiangbing Mao, Email: 284940931@qq.com.

Gang Tian, Email: tgang2008@126.com.

Jie Yu, Email: 49331300@qq.com.

Zhiqing Huang, Email: 33520558@qq.com.

Junqiu Luo, Email: 770353053@qq.com.

Daiwen Chen, Phone: 00 86 0835 2882088, Email: dwchen@sicau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bosaeus I. Fibre effects on intestinal functions (diarrhoea, constipation and irritable bowel syndrome) Clin Nutr Suppl. 2004;1(2):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nofrarías M, Martínez-Puig D, Pujols J, Majó N, Pérez JF. Long-term intake of resistant starch improves colonic mucosal integrity and reduces gut apoptosis and blood immune cells. Nutrition. 2007;23(11):861–870. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lattimer JM, Haub MD. Effects of dietary fiber and its components on metabolic health. Nutrients. 2010;2(12):1266–1289. doi: 10.3390/nu2121266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Aidy S, Derrien M, Merrifield CA, Levenez F, Doré J, Boekschoten MV, Dekker J, Holmes E, Zoetendal EG, Van Baarlen P. Gut bacteria–host metabolic interplay during conventionalisation of the mouse germfree colon. ISME J. 2013;7(4):743–755. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bäckhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307(5717):1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samuel BS, Gordon JI. A humanized gnotobiotic mouse model of host–archaeal–bacterial mutualism. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(26):10011–10016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602187103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flint HJ, Scott KP, Duncan SH, Louis P, Forano E. Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microbes. 2012;3(4):289–306. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La-ongkham O, Nakphaichit M, Leelavatcharamas V, Keawsompong S, Nitisinprasert S. Distinct gut microbiota of healthy children from two different geographic regions of Thailand. Arch Microbiol. 2015;197(4):561–573. doi: 10.1007/s00203-015-1089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chassard C, Delmas E, Robert C, Bernalier-Donadille A. The cellulose-degrading microbial community of the human gut varies according to the presence or absence of methanogens. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2010;74(1):205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker AW, Ince J, Duncan SH, Webster LM, Holtrop G, Ze X, Brown D, Stares MD, Scott P, Bergerat A. Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. ISME J. 2011;5(2):220–230. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandes J, Wang A, Su W, Rozenbloom SR, Taibi A, Comelli EM, Wolever TM. Age, dietary fiber, breath methane, and fecal short chain fatty acids are interrelated in Archaea-positive humans. J Nutr. 2013;143(8):1269–1275. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.170894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ong DK, Mitchell SB, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Irving PM, Biesiekierski JR, Smith S, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroen Hepatol. 2010;25(8):1366–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bond JH, Engel RR, Levitt MD. Factors influencing pulmonary methane excretion in man an indirect method of studying the in situ metabolism of the methane-producing colonic bacteria. J Exp Med. 1971;133(3):572–588. doi: 10.1084/jem.133.3.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller TL, Wolin M. Methanogens in human and animal intestinal tracts. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1986;7(2):223–229. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(86)80010-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjørneklett A, Jenssen E. Relationships between hydrogen (H2) and methane (CH4) production in man. Scand J Gastroentero. 1982;17(8):985–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cloarec D, Bornet F, Gouilloud S, Barry JL, Salim B, Galmiche J. Breath hydrogen response to lactulose in healthy subjects: relationship to methane producing status. Gut. 1990;31(3):300–304. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.3.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKay L, Brydon W, Eastwood M, Smith J. The influence of pentose on breath methane. Clin Nutr. 1981;34(12):2728–2733. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.12.2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Che L, Chen H, Yu B, He J, Zheng P, Mao X, Yu J, Huang Z, Chen D. Long-Term Intake of Pea Fiber Affects Colonic Barrier Function, Bacterial and Transcriptional Profile in Pig Model. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66(3):388–399. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2014.884229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Y-h LUO, Hua L, LUO J-Q, ZHANG K-Y. Yeast-Derived β-1, 3-Glucan Substrate Significantly Increased the Diversity of Methanogens During in vitro Fermentation of Porcine Colonic Digesta. J Integr Agr. 2013;12(12):2229–2234. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(13)60381-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zoetendal EG, Akkermans AD, De Vos WM. Temperature gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of 16S rRNA from human fecal samples reveals stable and host-specific communities of active bacteria. Appl Environ Microb. 1998;64(10):3854–3859. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3854-3859.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo Y-h, Wright A-DG, Y-l L, Li H, Yang Q-h, Luo L-J, Yang M-X. Diversity of methanogens in the hindgut of captive white rhinoceroses, Ceratotherium simum. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright A-DG, Northwood KS, Obispo NE. Rumen-like methanogens identified from the crop of the folivorous South American bird, the hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin) ISME J. 2009;3(10):1120–1126. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Good IJ. The population frequencies of species and the estimation of population parameters. Biometrika. 1953;40(3-4):237–264. doi: 10.1093/biomet/40.3-4.237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denman SE, Tomkins NW, McSweeney CS. Quantitation and diversity analysis of ruminal methanogenic populations in response to the antimethanogenic compound bromochloromethane. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;62(3):313–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kondo R, Nedwell DB, Purdy KJ, Silva SQ. Detection and enumeration of sulphate-reducing bacteria in estuarine sediments by competitive PCR. Geomicrobiol J. 2004;21(3):145–157. doi: 10.1080/01490450490275307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu K, Liu H, Du G, Chen J. Real-time PCR assays targeting formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase gene to enumerate acetogens in natural and engineered environments. Anaerobe. 2009;15(5):204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skillman LC, Evans PN, Naylor GE, Morvan B, Jarvis GN, Joblin KN. 16S ribosomal DNA-directed PCR primers for ruminal methanogens and identification of methanogens colonising young lambs. Anaerobe. 2004;10(5):277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dridi B, Henry M, El Khechine A, Raoult D, Drancourt M. High prevalence of Methanobrevibacter smithii and Methanosphaera stadtmanae detected in the human gut using an improved DNA detection protocol. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e7063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Federici S, Miragoli F, Pisacane V, Rebecchi A, Morelli L, Callegari ML. Archaeal microbiota population in piglet feces shifts in response to weaning: Methanobrevibacter smithii is replaced with Methanobrevibacter boviskoreani. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2015;362(10):fnv064. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker A. Say hello to our little friends. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(8):572–573. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weaver G, Krause J, Miller T, Wolin M. Incidence of methanogenic bacteria in a sigmoidoscopy population: an association of methanogenic bacteria and diverticulosis. Gut. 1986;27(6):698–704. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.6.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo Y-h, Su Y, Wright A-DG, Zhang L-l, Smidt H, Zhu W-y: Lean breed Landrace pigs harbor fecal methanogens at higher diversity and density than obese breed Erhualian pigs. Archaea 2012, 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/605289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Nava GM, Carbonero F, Croix JA, Greenberg E, Gaskins HR. Abundance and diversity of mucosa-associated hydrogenotrophic microbes in the healthy human colon. ISME J. 2012;6(1):57–70. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rea S, Bowman JP, Popovski S, Pimm C, Wright A-DG. Methanobrevibacter millerae sp. nov. and Methanobrevibacter olleyae sp. nov., methanogens from the ovine and bovine rumen that can utilize formate for growth. Int J Syst Evol Micr. 2007;57(3):450–456. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dridi B, Fardeau M-L, Ollivier B, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a methanogenic archaeon isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Micr. 2012;62(8):1902–1907. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.033712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.St-Pierre B, Wright A-DG. Molecular analysis of methanogenic archaea in the forestomach of the alpaca (Vicugna pacos) BMC Microbiol. 2012;12(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King EE, Smith RP, St-Pierre B, Wright A-DG. Differences in the rumen methanogen populations of lactating Jersey and Holstein dairy cows under the same diet regimen. Appl Environ Microb. 2011;77(16):5682–5687. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05130-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura N, Lin HC, McSweeney CS, Mackie RI, Gaskins HR. Mechanisms of microbial hydrogen disposal in the human colon and implications for health and disease. Food Sci Tech. 2010;1:363–395. doi: 10.1146/annurev.food.102308.124101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christl S, Gibson G, Cummings J. Role of dietary sulphate in the regulation of methanogenesis in the human large intestine. Gut. 1992;33(9):1234–1238. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.9.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernalier A, Lelait M, Rochet V, Grivet J-P, Gibson GR, Durand M. Acetogenesis from H2 and CO2 by methane-and non-methane-producing human colonic bacterial communities. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;19(3):193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1996.tb00212.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strocchi A, Furne J, Ellis C, Levitt M. Methanogens outcompete sulphate reducing bacteria for H2 in the human colon. Gut. 1994;35(8):1098–1101. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.8.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weijma J, Chi TM, Pol LWH, Stams AJ, Lettinga G. The effect of sulphate on methanol conversion in mesophilic upflow anaerobic sludge bed reactors. Process Biochem. 2003;38(9):1259–1266. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(03)00002-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vianna M, Holtgraewe S, Seyfarth I, Conrads G, Horz H. Quantitative analysis of three hydrogenotrophic microbial groups, methanogenic archaea, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and acetogenic bacteria, within plaque biofilms associated with human periodontal disease. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(10):3779–3785. doi: 10.1128/JB.01861-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsukamoto T, Miller G. Methanol as a carbon source for microbiological treatment of acid mine drainage. Water Res. 1999;33(6):1365–1370. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(98)00342-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao J, Zhang G, Mao Z-S, Li Y, Fang Z, Yang C. Influence of electron donors on the growth and activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Int J Miner Process. 2012;106:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.minpro.2012.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rey FE, Gonzalez MD, Cheng J, Wu M, Ahern PP, Gordon JI. Metabolic niche of a prominent sulfate-reducing human gut bacterium. P Natl Acad Sci Usa. 2013;110(33):13582–13587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312524110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The nucleotide sequences for the four clone libraries reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KU 362290 to KU362457.