Plants, like poikilothermic animals, face a requisite environmental challenge: they must maintain balanced cellular metabolism, and cell and organelle integrity, in the face of changes in temperature that may be both rapid and extreme. In particular, subfreezing temperatures, with the concomitant threats of ice formation and dehydration of the cell contents, present dangers that homothermic humans do not care to contemplate. Of course, Mother Nature provides freezing-tolerance mechanisms to those plants that are exposed to winter conditions. It is clear, however, that freezing tolerance is expensive, and, in this issue of PNAS, Cook et al. (1) take a step toward quantifying that expense. Cook et al. use metabolic profiling of three Arabidopsis lines under different conditions to provide a perspective on the many changes in metabolite pools that occur in plants shifted to low temperature and compare these changes with those occurring when freezing tolerance is induced genetically rather than by low temperature. The study discloses the extensive metabolic alterations associated with the induction of freezing tolerance.

Identification of Transcription Factors Regulating Cold Acclimation

One of the best-characterized temperature responses is the ability of plants to increase their freezing tolerance in response to a period of low, nonfreezing temperatures before the onset of winter-cold acclimation (CA). In nature, low, nonfreezing temperatures in late fall or early winter are the main triggers of CA (2). The observation that freezing tolerance is inducible rather than constitutive is the first clue that there is a substantial cost to providing freezing protection. Biologically, CA is complex, involving numerous changes in gene expression (2, 3). The extent of these changes suggests that almost every cellular process is altered during CA. However, it has been difficult to separate the processes that are critical to enhanced freezing tolerance from those that are merely responsive to low temperature. During freezing of plant tissues, ice first forms in the extracellular compartment, reducing the water potential and leading to loss of water from the cell by osmosis. Thus, dehydration is a large component of freezing stress. This explains the overlapping relationship between CA and dehydration (drought) responses both in terms of the biochemical changes and in transcriptional regulation (4, 5), and evidence indicates that multiple signaling pathways are involved in these responses (6, 7).

Many genes are transcriptionally up-regulated during CA (2, 3, 8). Most of these genes are expressed at 20–25°C and undergo 2- to 5-fold induction at low temperature (4°C). By contrast, one class of cold-regulated genes is extremely strongly induced by CA (typically 50- to 100-fold). These proteins are not enzymes, and their precise physiological functions remain a matter of debate although some probably act as cryoprotective proteins or dehydrins (2). We refer to these genes as COR (2). Gene fusion studies in Arabidopsis uncovered cis-acting elements in the promoter region of COR genes (2, 4). These elements are named drought-responsive elements (DREs) or low-temperature-responsive elements. Both contain a core sequence of CCGAC named C-repeat (CRT). The DRE/CRT elements have been used as bait to isolate two groups of DRE/CRT binding proteins by using the yeast one-hybrid system (9, 10). These proteins are called DREB (for DRE-binding factor) or CBF (for CRT-repeat binding factors). Five DRE/CRT-binding proteins have been isolated (10). Overexpression of either CBF1/DREB1A or CBF3/DREB1B in transgenic Arabidopsis induced the expression, at warm temperatures, of all COR genes that have the common DNA elements in their promoter region and provided plants with a constitutive increase in freezing tolerance (10). However, the transgenic lines with substantial levels of constitutive freezing tolerance are compromised in growth and development at higher temperatures (10, 11). This is also true of mutants that exhibit constitutive freezing tolerance (12, 13). It appears that the changes required to permit survival at freezing temperatures demand a price in terms of smooth and optional operation of normal cell processes.

Integration of Transcriptomics and Metabolomics

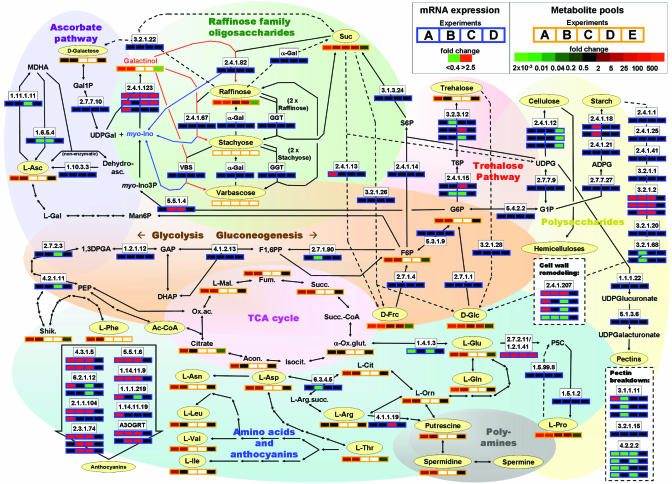

The availability of both transcriptome and metabolome data sets allows for the first time an integrative analysis of the expense associated with reconfiguring multiple metabolic pathways in plants shifted to low temperature (Fig. 1 and ref. 14). Based on recent results obtained with oligonucelotide microarrays, Fowler and Thomashow (3) reported cold-mediated up-regulation of 218 transcripts and down-regulation of 88 transcripts. Aside from transcripts known to be affected by cold treatment, the mRNA expression levels of genes involved in specific metabolic pathways were found to be affected [e.g., galactinol synthase of the raffinose family oligosaccharide pathway (RFO), 11 genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis, 7 genes involved in cell wall polysaccharide remodeling, and pyrroline 5-carboxylate synthase of the proline biosynthetic pathway]. In an independent study, Kreps et al. (15) compared the transcriptome changes of Arabidopsis in response to salt, osmotic, and cold stress and identified the same pathways as being affected by cold treatment (Fig. 1). Only 2% of the changes in transcript were found to be cold-specific, and the only known metabolic pathway genes among these are involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis, starch metabolism, and sterol biosynthesis (15). To investigate the relevance of the CBF cold response pathway in CA, Fowler and Thomashow (3) compared the transcript profiles of warm-grown transgenic Arabidopsis plants constitutively expressing CBF1, CBF2, or CBF3 with those of WT plants. Of the 41 transcripts up-regulated in all transgenic lines, 30 were identified as genuine members of the CBF regulon. Whereas anthocyanin accumulation appeared to be independent of CBF expression, the transcripts of galactinol synthase and pyrroline 5-carboxylate synthase were highly up-regulated in the constitutive CBF expression lines. Cook et al. (1) report increased levels of various monosaccharides and disaccharides, amino acids, polyamines, ascorbate, and intermediates of the tricarboxylic acid cycle in cold-treated Arabidopsis plants (Fig. 1). The enhanced proline levels correlate well with the previously reported increase in pyrroline 5-carboxylate synthase transcript levels (3, 15), thus confirming the previously reported correlation between proline levels and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis (16). The transcriptional up-regulation of the RFO pathway by cold treatment (3, 15) was also reflected in the increased accumulation of fructose, glucose, galactinol, sucrose, melibiose, and raffinose (1). Notably, the same sugars were found at elevated levels in crosses between the Col-0 and C24 accessions of Arabidopsis that showed an increased freezing tolerance compared with their parents (Fig. 1 and ref. 17). Because the expression levels of other genes involved in the RFO pathway remained unchanged in cold-treated plants (3, 15), the data from several independent experiments indicate that myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase and galactinol synthase might play key roles in regulating flux through the RFO pathway.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of low-temperature effects on the regulation of metabolic pathways in Arabidopsis using the biopathat tool (14). The dynamic rectangular boxes representing genes (blue frame) are positioned on top of the biochemical reaction arrow, whereas boxes indicating metabolite pools (orange frames) are below the compound name. Genes representing different isozymes are stacked. Colors are used to represent changes of expression from a mean or control value (red for up-regulation and green for down-regulation) and color intensity to represent the level of the change (only for metabolites). Transcript changes are shown for the following experiments (up- or down-regulation versus an appropriate control): A, cold-treated Arabidopsis Ws-1 plants (3); B, cold-treated leaves of Arabidopsis Col-0 plants (15); C, cold-treated roots of Arabidopsis Col-0 plants (15); D, warm-grown plants overexpressing CBF 1, CBF2, or CBF3. Metabolite changes are shown for the following experiments (up- or down-regulation versus an appropriate control): A, cold-treated Arabidopsis Ws-1 plants (1); B, warm-grown plants overexpressing CBF 1, CBF2, or CBF3 (1); C, ratio of metabolite pools in the F1 generation of a cross between Arabidopsis accessions Col-0 and C24 versus C24 parent (17); D, ratio of metabolite pools in the F1 generation of a cross between Arabidopsis accessions Col-0 and C24 versus Col-0 parent (17); E, ratio of metabolite pools in the freezing-sensitive Cvi-1 mutant versus WT (Ws-1) (1).

Using GC coupled to time-of-flight MS (18), Cook et al. (1) detected a total of 114 polar metabolites, the pool sizes of which increased substantially in response to low temperature. The identity of ≈30 of these metabolites was determined. However, the structure of most cold-induced metabolites remains elusive. These results highlight a serious shortcoming of metabolomics. The currently available high-throughput technologies provide massive amounts of data that can be used to generate hypotheses (e.g., metabolite X might be involved in tolerance to treatment Y), but as long as the metabolites of interest remain unidentified, the usefulness of these technologies is limited. Other high-throughput approaches to improve the identification of unknown metabolites have been proposed (19), but for certain metabolites, “classical” phytochemical approaches may have to be used to unravel their identity. Even if the remaining unknown metabolites detected by Cook et al. (1) could be identified, the use of a single extraction step coupled with a single detection method (GC-time of flight) leaves the vast majority of the metabolome untapped. Multiparallel approaches, which use integrated protocols for the extraction and analysis of various metabolite classes, will have to be used to elevate the coverage of metabolite analyses to a true metabolomic scale. Novel, innovative approaches are required to enhance our ability to identify metabolites in a high-throughput manner. The future of metabolomics as a discovery tool not only will depend on technological advances but also will require communitywide efforts to share well characterized reference materials. The recent establishment of an online forum to facilitate the interaction between laboratories (www.metabolomics.nl) marks an important first step in this direction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant IBN-0084329 and the Agricultural Research Center at Washington State University.

See companion article on page 15243.

References

- 1.Cook, D., Fowler, S., Fiehn, O. & Thomashow, M. F. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15243–15248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomashow, M. F. (1999) Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 571–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowler, S. & Thomashow, M. F. (2002) Plant Cell 14, 1675–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seki, M., Kamei, A., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. & Shinozaki, K. (2003) Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 14, 194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang, J. Z., Creelman, R. A. & Zhu, J. K. (2004) Plant Physiol. 135, 615–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shinozaki, K. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. (2000) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3, 217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiong, L., Ishitani, M. & Zhu, J. K. (1999) Plant Physiol. 19, 569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chinnusamy, V., Ohta, M., Kanrar, S., Lee, B. H., Hong, X., Agarwal, M. & Zhu, J. K. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 1043–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stockinger, E. J., Gilmour, S. J. & Thomashow, M. F. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 1035–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu, Q., Kasuga, M., Sakuma, Y., Abe, H., Miura, S., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. & Shinozaki, K. (1998) Plant Cell 10, 1391–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasuga, M., Liu, Q., Miura, S., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. & Shinozaki, K. (1999) Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xin, Z. & Browse, J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7799–7804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vlachonasios, K. E., Thomashow, M. F. & Triezenberg, S. J. (2003) Plant Cell 15, 626–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lange, B. M. & Ghassemian, M. (2004) Phytochemistry, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Kreps, J. A., Wu, Y., Chang, H. S., Zhu, T., Wang, X. & Harper J. F. (2002) Plant Physiol. 130, 2129–2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nanjo, T., Kobayashi, M., Yoshiba, Y., Kakubari, Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. & Shinozaki, K. (1999) FEBS Lett. 461, 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rohde, P., Hincha, D. k. & Heyer, A. G. (2004) Plant J. 38, 790–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weckwerth, W., Louriero, M. E., Wenzel, K. & Fiehn, O. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7809–7814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bino, R. J., Hall, R. D., Fiehn, O., Kopka, J., Saito, K., Draper, J., Nikolau, B. J., Mendes, P., Roessner-Tunali, U., Beale, M. H., et al. (2004) Trends Plant Sci. 9, 418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]