Abstract

Objective

Childhood trauma is recognized as an important risk factor in suicidal ideation, however it is not fully understood how the different types of childhood maltreatment influence suicidal ideation nor what variables mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation. This study examined the path from childhood trauma to suicidal ideation, including potential mediators.

Methods

A sample of 211 healthy adults completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), Beck scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSI), Functional Social Support Questionnaire (FSSQ) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Path analysis was used to investigate the relationship among study variables.

Results

Of the several types of childhood maltreatment we considered, only childhood sexual abuse directly predicted suicidal ideation (β=0.215, p=0.001). Childhood physical abuse (β=0.049, 95% confidence interval: 0.011–0.109) and childhood emotional abuse (β=0.042, 95% confidence interval: 0.001–0.107) indirectly predicted suicidal ideation through their association with anxiety. Childhood neglect indirectly predicted suicidal ideation through association with perceived social support (β=0.085, 95% confidence interval: 0.041–0.154).

Conclusion

Our results confirmed that childhood sexual abuse is a strong predictor of suicidal ideation. Perceived social support mediated the relationship between suicidal ideation and neglect. Anxiety fully mediated the relationship between suicidal ideation and both physical abuse and emotional abuse. Interventions to reduce suicidal ideation among survivors of childhood trauma should focus on anxiety symptoms and attempt to increase their social support.

Keywords: Childhood traumatic experience, Sexual abuse, Suicidal ideation, Anxiety, Perceived social support

INTRODUCTION

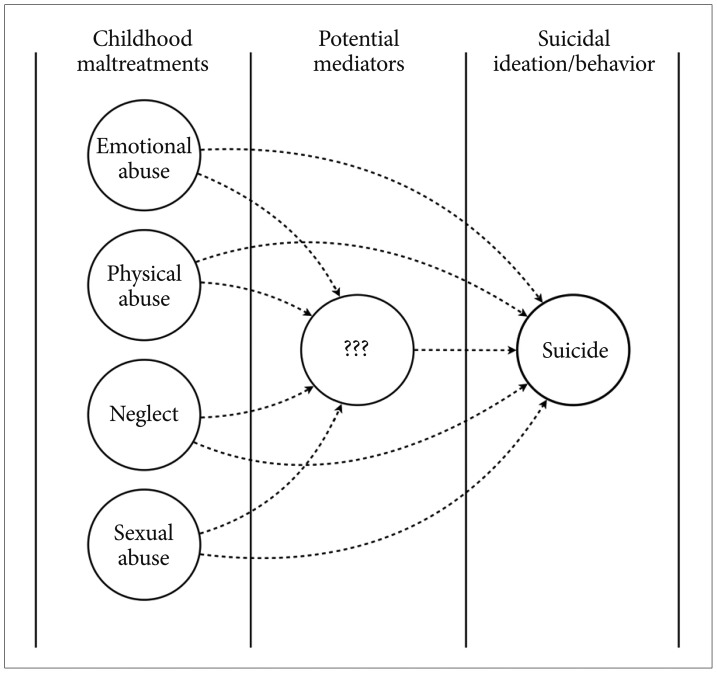

Suicide is a multifaceted phenomenon with multiple risk factors including psychosocial,1 neurobiological2 and psycho-pathological factors.3 It is recognized that childhood trauma can lead to suicidal ideation and behavior.4,5,6 Although childhood maltreatment predicts suicidal ideation and behavior across the lifespan, the precise role of particular types of childhood maltreatment and the mediators of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicide have not been fully investigated (Figure 1).5,7

Figure 1. Uninvestigated pathways from childhood maltreatment to suicide.

Childhood maltreatment is an umbrella terms encompassing childhood sexual, physical and emotional abuse and neglect.5 Childhood sexual abuse is typically defined as unwanted, inappropriate sexual activity with perpetrator (e.g., verbal sexual harassment, exhibitionism).8 Physical abuse is defined as any intentional act which have potential to or do cause injury or trauma by an older person.9 Emotional abuse, also referred to as psychological abuse is defined as behavior that causes psychological trauma or stress. It can include verbal assaults, any threatening, demeaning, terrorizing or humiliating remarks.10 Finally, neglect is defined as a deficit in meeting a child's basic physical needs (i.e., food, shelter, safety) or psychological needs (i.e., encouragement, belongingness, warmth, love and support).11 Childhood sexual12,13,14 and physical abuse7,15,16 have been known to be linked to suicidal ideation. It has been suggested that research into the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicide has focused disproportionately on sexual and physical abuse.7 There have been relatively few studies examining the relationship between suicide and childhood emotional abuse and neglect. A recent systematic review noted that only 8 studies have considered the relationship between suicide and emotional abuse and neglect, compared with 52 studies considering sexual abuse and 24 considering physical abuse.5

Recent research has suggested that the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal ideation may be mediated by other important variables,5 and that targeting such mediators is crucial to effective mental health interventions to reduce suicidal risk. There have, however, been only a few studies examining potential mediators such as psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial factors.7,17,18 Felzen17 found that interpersonal problems mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal behavior. Miller, Adams, Esposito-Smythers, Thompson Proctor18 reported that parental relationships, friendships and depression mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal ideation. High perceived social support has been reported to be protective against suicide.19 Several studies have indicated that childhood trauma is associated with depression and anxiety in adulthood.20,21,22 It has also been suggested that anxiety and depression mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and suicide.13

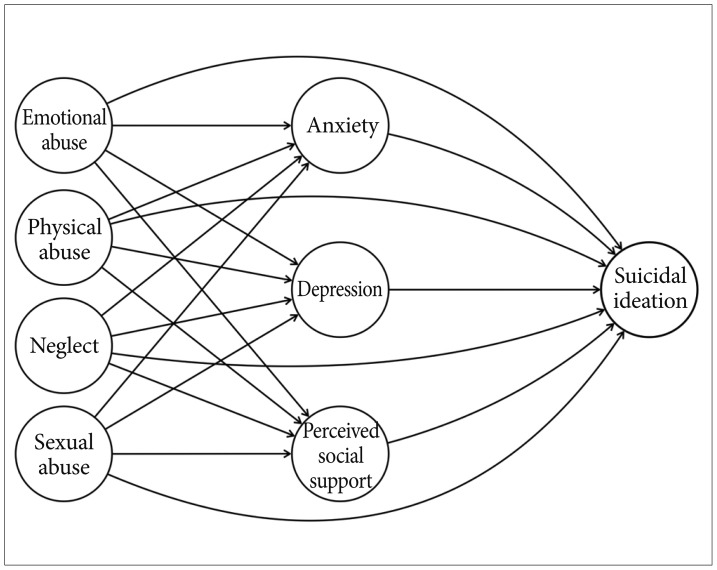

With these findings in mind, the aim of this study was to explore the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal ideation in a community sample. We hypothesized that 1) childhood sexual, physical and emotional abuse and childhood neglect would be directly or indirectly associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation in adulthood, 2) perceived social support, depression and anxiety would partially mediate the relationship between suicidal ideation and these forms of childhood maltreatment. We investigated whether the established relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal ideation could be explained by a model that posits perceived social support, depression and anxiety as mediators. The hypothesized model is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Hypothesized model.

METHODS

Participants

The sample consisted of 211 healthy adults aged 20 to 32 years old (47.39% women). Subjects were screened by the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition in order to exclude current and/or lifetime Axis I23 and II disorders.24 Subjects with organic brain disease, a hearing problem, or family history of a mental disorder were also excluded. All subjects were no smoking, and right handed. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital.

Measures

Childhood emotional abuse and neglect

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)25 was used to measure childhood maltreatment. The CTQ (28 items) comprises four subscales: sexual abuse (5 items; e.g., was molested, was touched sexually), physical abuse (5 items; e.g., hit hard enough to leave bruises, hit badly enough to be noticed), emotional abuse (5 items; e.g., felt hated by family, family said hurtful things), and neglect (13 items; e.g., made to feel important, got taken to doctor). Items are rated using a 5-point Likert-type scale. In addition, It has been suggested that a cutoff score of 9 on the sexual abuse subscale and 12 on the physical abuse subscale in psychiatric samples.25 All the subscales have been shown to have good internal consistency and reliability (α=0.77–0.83 in Korean samples).26

Suicidal ideation

The Beck scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSI) Beck, Steer Ranieri27 was used to assess suicidal ideation. It has good internal consistency (α=0.74) and moderately high correlations with other measures of suicidal ideation and hopelessness in Korean samples.28

Perceived social support

The Functional Social Support Questionnaire (FSSQ)29 was used to assess perceived social support. It is a 13-item self-report questionnaire which has excellent internal consistency (α=0.89) in Korean samples.30

Anxiety and depression

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Zigmond Snaith31 was used to measure anxiety and depression. The HADS consists of 2 subscales: anxiety (7 items) and depression (7 items). Both subscales have been demonstrated to have excellent internal consistency (both α=0.89) in a Korean sample.32

Data analysis

We evaluated our model of suicidal ideation using path analysis conducted with Mplus. Path analysis is a statistical method for calculating the strength of relationships among constructs.33 Path analysis has two over correlation analyses: 1) the ability to assess several relationships simultaneously and 2) the ability to specify the directionality of relationships. In path analysis there are two levels of analysis, relating to the significance of individual paths between variables and the overall fit of the model to the data. Overall model fit is evaluated using several indices: 1) the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA; conventional criteria are good fit: ≤0.05, adequate fit: ≤0.08), 2) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; adequate fit: ≥0.95) and 3) the Tucker-Lewis Index(TLI; adequate fit: >0.95).34 The bootstrap procedure described by Preacher Hayes35 was used to estimate the size of the indirect effects (n=5000 resamples). Other statistical variables were calculated using SPSS.

RESULTS

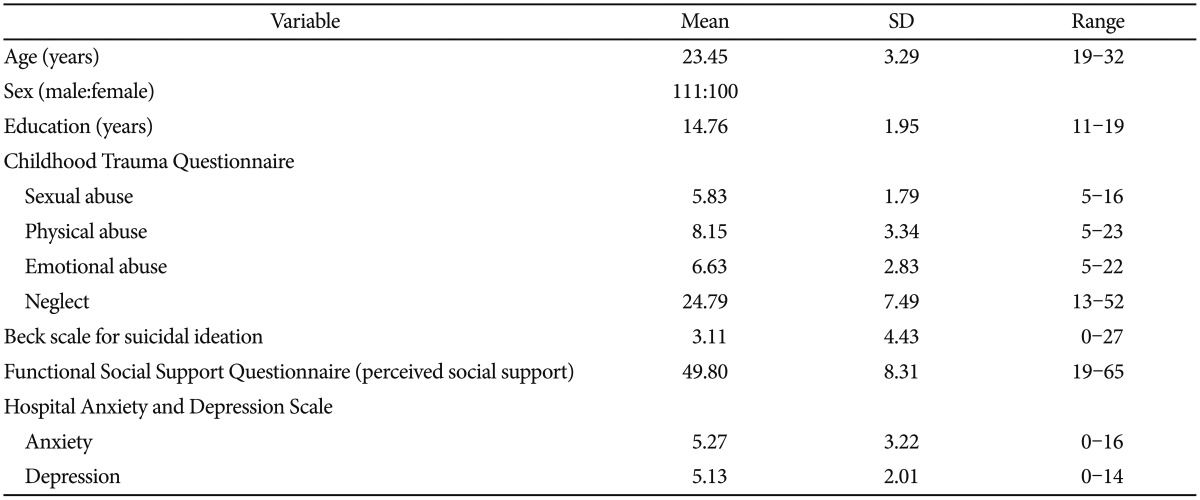

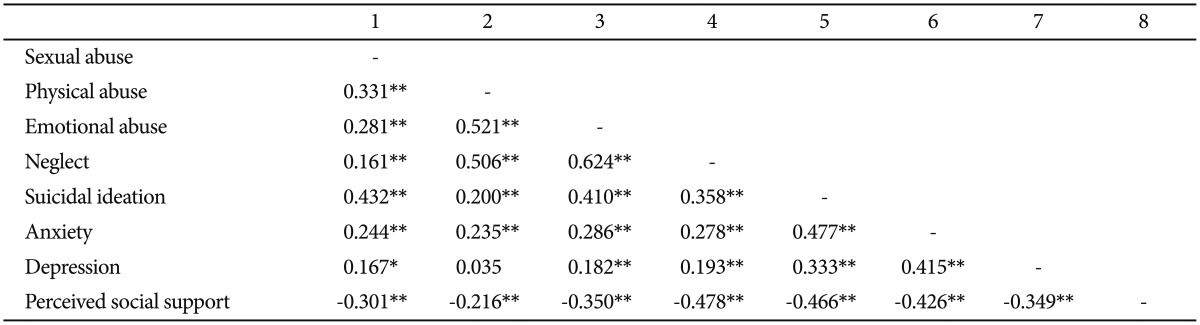

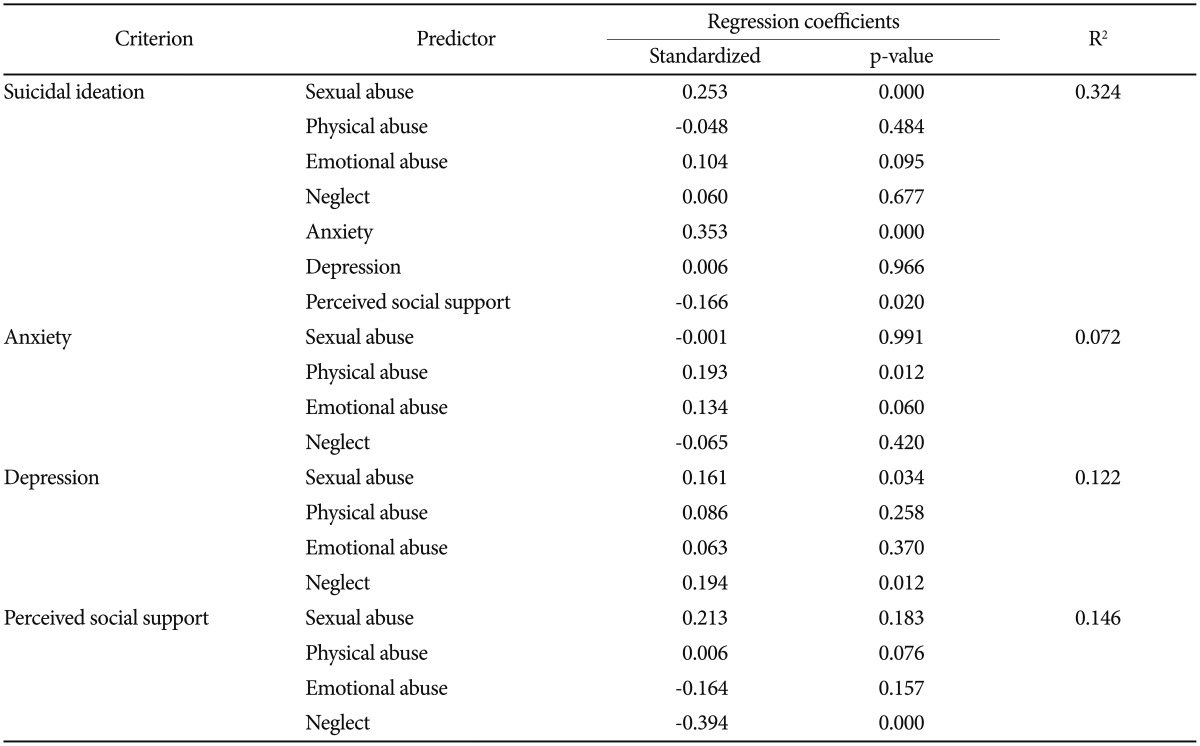

The demographic and clinical profile of the sample is presented in Table 1. Correlation analyses demonstrated that associations between variables were in the expected direction (Table 2). Path analysis showed that the hypothesized model (Figure 2) was a poor fit to the data (RMSEA=0.167; CFI=0.889; TLI= 0.749). The parameter estimates were evaluated, and the results are shown in Table 3.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical profile of the sample.

Table 2. Correlations among study variables (N=211).

*p<.,**p<.

Table 3. Results of path analysis (N=211).

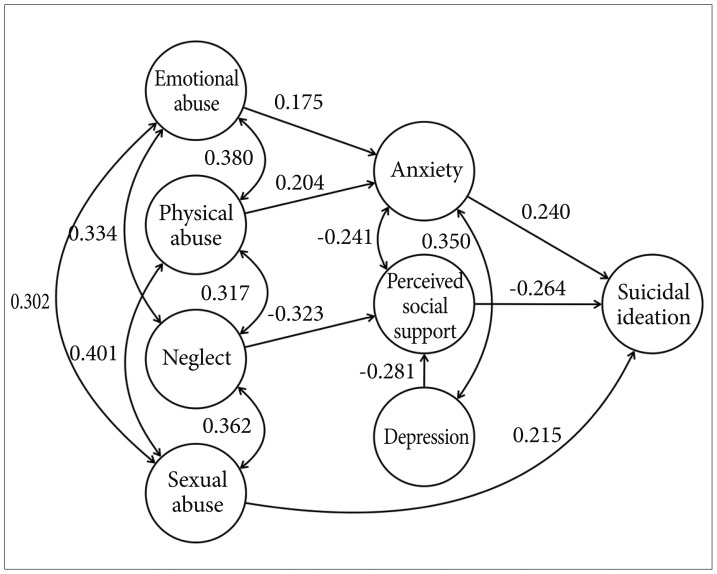

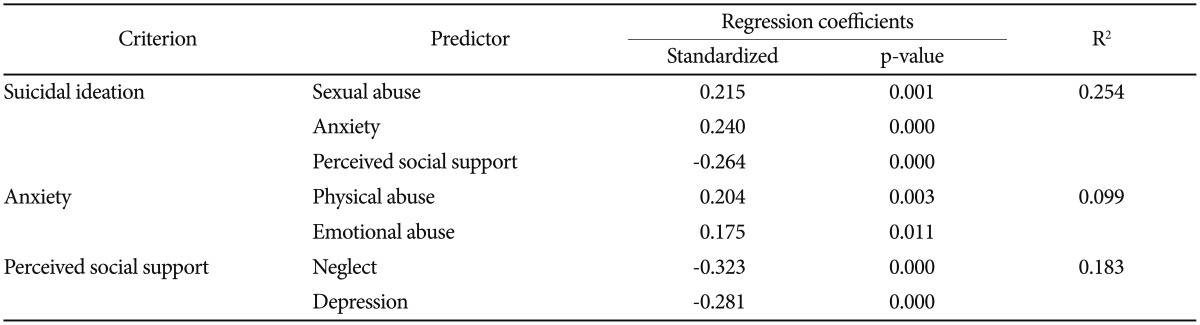

On the basis of these results we trimmed our hypothesized model. In accordance with the modification index we removed insignificant paths and added a path from depression to perceived social support (Figure 3). Path analysis indicated that the trimmed model was a good fit to the data (RMSEA=0.044; CFI=0.969; TLI=0.958). The results of path analysis of the trimmed model are presented in Table 4 and Figure 3. The path analysis revealed that sexual abuse and anxiety were positive predictors of suicidal ideation (β=0.215, p=0.001; β=0.240, p<0.000 respectively) whilst perceived social support was a negative predictor (β=-0.264, p<0.000). The results also showed that perceived social support fully mediated the relationship between suicidal ideation and neglect (β=0.085, 95% confidence interval: 0.041–0.154) and depression (β=0.074, 95% confidence interval: 0.030–0.143). Anxiety fully mediated the relationship between suicidal ideation and physical abuse (β=0.049, 95% confidence interval: 0.011–0.109) and emotional abuse (β=0.042, 95% confidence interval: 0.001–0.107).

Figure 3. Trimmed model.

Table 4. Results of path analysis of trimmed model (N=211).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the pathway from different types of childhood maltreatment to suicidal ideation and explored potential mediators of the relationship. Of several types of childhood maltreatment investigated, only childhood sexual abuse directly predicted suicidal ideation. Childhood physical and emotional abuse indirectly predicted suicidal ideation through their association with anxiety. Childhood neglect indirectly predicted suicidal ideation through its association with perceived social support.

Consistent with previous research,12,13,14 our findings showed that childhood sexual abuse is directly associated with suicidal ideation. Childhood sexual abuse was still associated with suicidal ideation after controlling for the effects of other forms of childhood maltreatment; this is not surprising because childhood sexual abuse is recognized as form of trauma which has serious, long-term psychological sequelae such as sexual disturbance, depression, anxiety, fear, anger and suicidal ideation in later adulthood.36,37 It has also been suggested that childhood sexual abuse is associated with medical problems such as chronic pelvic pain38 and even abnormalities of brain developments.39,40 These results corroborate previous research suggesting that childhood sexual abuse is a serious risk factor for suicide in adulthood.

Unlike previous studies7,15,16,41 we did not find that childhood physical or emotional abuse and childhood neglect were direct predictors of suicidal ideation. We did, however, find indirect positive associations between suicidal ideation and childhood physical or emotional abuse which were mediated by anxiety. We also found an indirect positive association between childhood neglect and suicidal ideation which was mediated by perceived lack of social support.

Anxiety has been identified as an important risk factor for suicide in adults. Several studies have suggested that anxiety disorders are associated with an increased risk of suicide.42,43,44 A large population-based longitudinal study showed that after adjusting for sociodemographic factors and the presence of all other mental disorders (except anxiety disorder), there were significant associations between suicidal ideation and presence of anxiety disorders. The same study found that comorbid anxiety disorder increased the risk of suicide attempts relative to the risk associated with mood disorder alone.44 A number of studies have reported that anxiety symptoms are associated with suicide.45,46 Some previous studies have reported that childhood physical and emotional abuse and childhood neglect are directly related to suicidal ideation, whereas some studies have reported that childhood physical and emotional abuse are associated with anxiety.47,48,49 Recently it was reported that among women with postpartum depression, having frequent thoughts about self-harm was associated with childhood physical abuse and anxiety symptom.50 In light of these findings our results suggest that anxiety plays an important role as a mediator of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal ideation.

It is not surprising that perceived social support fully mediated the relationship between childhood neglect and suicidal ideation because both perceived social support and neglect relate to lack of affection and support from others. High perceived social support has been recognized as strongly protective against suicide.51,52 In addition, the mediating role of perceived social support was repeatedly reported in the path analysis to predict the suicide.53,54 It has also been shown that perceived social support mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and various adverse outcomes.55,56 Interestingly, depression did not directly predict suicidal ideation. Instead, depression indirectly predicted suicidal ideation through perceived social support. There have been several studies that depression is related to suicidal ideation, however, recent study showed that depression did not predict suicidal ideation directly, predicted suicidal ideation through interpersonal variables such as belongingness.57 The results of our study suggest that anxiety and perceived social are important mediators of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal ideation and hence should be considered important targets for interventions to reduce suicide risk.

There are some limitations to this study. First, as it is based on a cross-sectional design we cannot confirm causal relationships between variables; further longitudinal research would be needed to do so. Second, our suggested model might be suitable for only suicide ideation because suicide attempt and ideation are different. It might be useful to test the model in a sample of individuals with a history of attempted suicide. Lastly, the participants in this study were healthy individuals without any history of psychiatric disorder; it is therefore important to replicate our findings in clinical samples. And also our data of childhood maltreatment, depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation score were positively skewed. However, we conducted square root transformation on theses variable to bring it closer to normal distribution, and analyzed the transformed and original data both. It was found that the pattern of results did not meaningfully differ.

Despite these limitations this study has demonstrated the utility of a model of the paths between childhood maltreatment and suicidal ideation in adults. Our results suggest that sexual abuse is the form of childhood maltreatment most strongly associated with suicide risk, and that anxiety and social support are important mediators of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal ideation. We therefore recommend that clinicians should screen patients for anxiety and lack of social support in order to identify those at greater risk of suicidal ideation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF), funded by the Korean government (NRF-2015M3C7A1028252).

References

- 1.King RA, Schwab-Stone M, Flisher AJ, Greenwald S, Kramer RA, Goodman SH, et al. Psychosocial and risk behavior correlates of youth suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:837–846. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lester D. Why People Kill Themselves: A 1990s Summary of Research Findings on Suicidal Behavior. Springfield, IL, England: Charles C Thomas, Publisher; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S, Fisher P, Schwab-Stone M, Kramer R, et al. Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:915–923. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King CA, Merchant CR. Social and interpersonal factors relating to adolescent suicidality: a review of the literature. Arch Suicide Res. 2008;12:181–196. doi: 10.1080/13811110802101203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller AB, Esposito-Smythers C, Weismoore JT, Renshaw KD. The relation between child maltreatment and adolescent suicidal behavior: a systematic review and critical examination of the literature. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013;16:146–172. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0131-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harford TC, Yi HY, Grant BF. Associations between childhood abuse and interpersonal aggression and suicide attempt among US adults in a national study. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson R, Proctor LJ, English DJ, Dubowitz H, Narasimhan S, Everson MD. Suicidal ideation in adolescence: examining the role of recent adverse experiences. J Adolesc. 2012;35:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkelhor D. The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18:409–417. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malinosky-Rummell R, Hansen DJ. Long-term consequences of childhood physical abuse. Psychol Bull. 1993;114:68–79. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glaser D. Emotional abuse and neglect (psychological maltreatment): a conceptual framework. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:697–714. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crouch JL, Milner JS. Effects of child neglect on children. Crim Justice Behav. 1993;20:49–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Smailes EM. Childhood abuse and neglect: specificity of effects on adolescent and young adult depression and suicidality. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1490–1496. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson R, Briggs E, English DJ, Dubowitz H, Lee LC, Brody K, et al. Suicidal ideation among 8-year-olds who are maltreated and at risk: findings from the LONGSCAN studies. Child Maltreat. 2005;10:26–36. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenberg ME, Ackard DM, Resnick MD. Protective factors and suicide risk in adolescents with a history of sexual abuse. J Pediatr. 2007;151:482–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bensley LS, Van Eenwyk J, Spieker SJ, Schoder J. Self-reported abuse history and adolescent problem behaviorsand suicidal behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan SJ, Pelcovitz D, Salzinger S, Mandel F, Weiner M, Labruna V. Adolescent physical abuse and risk for suicidal behaviors. J Interpers Violence. 1999;14:976–988. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felzen JC. Child maltreatment 2002: recognition, reporting and risk. Pediatr Int. 2002;44:554–560. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2002.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller AB, Adams LM, Esposito-Smythers C, Thompson R, Proctor LJ. Parents and friendships: a longitudinal examination of interpersonal mediators of the relationship between child maltreatment and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220:998–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller AB, Esposito-Smythers C, Leichtweis RN. Role of social support in adolescent suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP. The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: a community study. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20:7–21. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Dill L, Schroeder AF, DeChant HK, et al. Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood abuse: unhealed wounds. JAMA. 1997;277:1362–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hovens JG, Wiersma JE, Giltay EJ, Van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, et al. Childhood life events and childhood trauma in adult patients with depressive, anxiety and comorbid disorders vs. controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122:66–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders SCID-I: Clinician Version. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Pub; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu J, Park J, Park D, Ryu S, Ha J. Validation of the Korean childhood trauma questionnaire: the practical use in counselling and therapeutic intervention. Korean J Health Psychol. 2009;14:563–578. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ranieri WF. Scale for suicide ideation: Psychometric properties of a self report version. J Clin Psychol. 1988;44:499–505. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198807)44:4<499::aid-jclp2270440404>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H, Kuwn J. Validation for the Beck scale for suicide ideation with Korean university students. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2009;28:1155–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broadhead W, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire: Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988;26:709–723. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suh S, Im Y, Lee SH, Park M, Yoo T. A study for the development of Korean version of the Duke-UNC functional social support questionnaire. Korean J Fam Med. 1997;18:250–260. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh SM, Min KJ, Park DB. A study on the standardization of the hospital anxiety and depressed scale for Koreans: a comparison of normal, depressed and anxious groups. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1999;38:289–296. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klem L. Path Analysis. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, daCosta GA, Akman D, Cassavia E. A review of the long-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16:101–118. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90011-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumann DA, Houskamp BM, Pollock VE, Briere J. The long-term sequelae of childhood sexual abuse in women: a meta-analytic review. Child Maltreat. 1996;1:6–16. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R, Hills R, Khan K. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332:749–755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38748.697465.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teicher MH, Andersen SL, Polcari A, Anderson CM, Navalta CP, Kim DM. The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andersen SL, Tomada A, Vincow ES, Valente E, Polcari A, Teicher MH. Preliminary evidence for sensitive periods in the effect of childhood sexual abuse on regional brain development. J Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2014;20:292–301. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20.3.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Locke TF, Newcomb MD. Psychosocial predictors and correlates of suicidality in teenage Latino males. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2005;27:319–336. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allgulander C, Lavori PW. Excess mortality among 3302 patients with ‘pure’ anxiety neurosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:599–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310017004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mannuzza S, Aronowitz B, Chapman T, Klein DF, Fyer AJ. Panic disorder and suicide attempts. J Anxiety Disord. 1992;6:261–274. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, Asmundson GJ, ten Have M, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1249–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fawcett J, Scheftner WA, Fogg L, Clark DC, Young MA, Hedeker D, et al. Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am J psychiatry. 1990;147:1189–1194. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.9.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohring R, Apter A, Ratzoni G, Weizman R, Tyano S, Plutchik R. State and trait anxiety in adolescent suicide attempters. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:154–157. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199602000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mancini C, Van Ameringen M, MacMillan H. Relationship of childhood sexual and physical abuse to anxiety disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:309–314. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferguson KS, Dacey CM. Anxiety, depression, and dissociation in women health care providers reporting a history of childhood psychological abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21:941–952. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spertus IL, Yehuda R, Wong CM, Halligan S, Seremetis SV. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect as predictors of psychological and physical symptoms in women presenting to a primary care practice. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1247–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sit D, Luther J, Buysse D, Dills JL, Eng H, Okun M, et al. Suicidal ideation in depressed postpartum women: associations with childhood trauma, sleep disturbance and anxiety. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;66-67:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D'Attilio JP, Campbell BM, Lubold P, Jacobson T, Richard JA. Social support and suicide potential: preliminary findings for adolescent populations. Psychol Rep. 1992;70:76–78. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1992.70.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rigby K, Slee P. Suicidal ideation among adolescent school children, involvement in bully-victim problems, and perceived social support. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1999;29:119–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson MP, Kaslow NJ, Short LM, Wyckoff S. The mediating roles of perceived social support and resources in the self-efficacy-suicide attempts relation among African American abused women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:942–949. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kotler M, Iancu I, Efroni R, Amir M. Anger, impulsivity, social support, and suicide risk in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:162–167. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tremblay C, Hébert M, Piché C. Coping strategies and social support as mediators of consequences in child sexual abuse victims. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23:929–945. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Runtz MG, Schallow JR. Social support and coping strategies as mediators of adult adjustment following childhood maltreatment. Child Abuse Neglect. 1997;21:211–226. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davidson CL, Wingate LR, Grant DM, Judah MR, Mills AC. Interpersonal suicide risk and ideation: the influence of depression and social anxiety. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30:842–855. [Google Scholar]