Abstract

Growing recognition of disparities in early childhood language environments prompt examination of parent-child interactions which support vocabulary. Research links parental sensitivity and cognitive stimulation to child language, but has not explicitly contrasted their effects, nor examined how effects may change over time. We examined maternal sensitivity and stimulation throughout infancy using two observational methods – ratings of parents’ interaction qualities, and coding of discrete parenting behaviors - to assess the relative importance of these qualities to child vocabulary over time, and determine whether mothers make related changes in response to children’s development. Participants were 146 infants and mothers, assessed when infants were 14, 24, and 36 months. At 14 months, sensitivity had a stronger effect on vocabulary than did stimulation, but the effect of stimulation grew throughout toddlerhood. Mothers’ cognitive stimulation grew over time, whereas sensitivity remained stable. While discrete parenting behaviors changed with child age, there was no evidence of trade-offs between sensitive and stimulating behaviors, and no evidence that sensitivity moderated the effect of stimulation on child vocabulary. Findings demonstrate specificity of timing in the link between parenting qualities and child vocabulary which could inform early parent interventions, and supports a reconceptualization of the nature and measurement of parental sensitivity.

Keywords: specificity, parental sensitivity, cognitive stimulation, language development, parent-child interaction, measurement of parenting, quantitative observational methods

Parenting young children is a complex, multi-faceted endeavor; parents are tasked with providing the foundations of healthy development for children across multiple domains, and adjusting to almost constant change in child behaviors and needs. In addition to providing for basic physical needs, dimensions of parenting include the provision of love and affection, instilling discipline, and providing learning and cognitive stimulation opportunities for children (Bradley, 2006; Hindman & Morrison, 2012). Children’s development and well-being are dependent on both the stimulation and sensitivity they receive early in life (Bradley, Corwyn, Burchinal, McAdoo, & García Coll, 2001; Halle, Anderson, Blasberg, Chrisler, & Simkin, 2011; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). These dimensions of caregiving – cognitive stimulation and sensitivity – are often presented as conceptually distinct and measured on separate scales (Halle et al., 2011); parents may be more effective in one dimension than in another, and both contribute in unique ways to child development (Grusec & Davidov, 2010), including early vocabulary (e.g., Rodriguez & Tamis-LeMonda, 2011; Rollins, 2003; Tomasello & Farrar, 1986), an important predicator of later language and school readiness skills (Ramey & Ramey, 1999). However, parents who are sensitive tend to be more stimulating (Holden & Miller, 1999), and there is overlap in behaviors characterized as sensitive or stimulating.

Based on evidence that language stimulation – the quantities of complex language to which children are exposed – influence their early vocabulary development (e.g., Hart & Risley, 1992; Tamis-LeMonda, Baumwell, & Cristofaro, 2012), recent city- and state-level programs aim to enhance early language environments for young children in order to reduce income-based disparities in children’s vocabulary development. These programs focus on creating stimulating language environments with an emphasis on quantity of words and concepts to which children are exposed (e.g., Leffel & Suskind, 2013; Suskind, et al., 2013). However, such broad campaigns and intervention programs may inadvertently ignore the important role of the quality of parent-child interactions which create optimal language-learning environments, particularly the role of caregivers’ sensitivity to children’s interests, attention, and cues; for example, the suite of “Word Gap” campaigns under the coordinated effort “Too Small to Fail: Talking is Teaching,” places emphasis on caregivers’ speech quantity to stimulate child word learning, with a less obvious role for the qualities of interactions. What may be particularly important for children’s development, and contribute to the distinctiveness of stimulating versus sensitive interactions, is the degree of emphasis placed on one type of parental behavior over another, and how these emphases may shift over time in response to children’s developmental needs. It is the differences in emphases parents place on these interaction qualities over time, and their implications for children’s vocabulary development, that are addressed in this study.

Broadly speaking, sensitivity refers to the warm, contingent responses parents provide to children based on accurately reading and appropriately responding to their affective, vocal, and gestural cues (Love et al., 2005; Shin, Park, Ryu, & Seomun, 2008); whereas stimulation involves parents’ efforts toward promoting children’s cognitive development, and is inclusive of intentional teaching efforts which may be parent-directed rather than contingent upon children’s cues (Martin, Ryan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2007). In early childhood, both sensitivity and stimulation are typically measured through observation of parent-child interactions (e.g., Farah et al., 2008; Love et al., 2005), often focusing on communicative aspects of these interactions, including features of parents’ language (e.g., Page, Wilhelm, Gamble, & Card, 2010; Pan, Rowe, Singer, & Snow, 2005). Thus, while sensitivity and stimulation may emphasize distinct behaviors, both have been linked to child language, particularly vocabulary development (Halle et al., 2011).

Research on parental supports for child language development has identified specificity in parenting behaviors associated with more advanced language (e.g., Baumwell, Tamis-LeMonda, & Bornstein, 1997; Tamis-LeMonda, Bornstein, & Baumwell, 2001). Specificity refers to the idea that different parenting behaviors have distinct developmental consequences for children, rather than the notion that any high quality parenting behavior supports all aspects of child development. For example, certain parenting behaviors may affect specific skills but not others within a domain (e.g., Tamis-LeMonda, Bornstein, Baumwell, & Damast, 1996), or the effects of a particular parenting dimension may depend on the specific timing of parents’ behaviors relative to child age (Bornstein & Tamis-LeMonda, 1997; Farah et al., 2008); it is this latter type of specificity on which we focus the questions of the current study. During early childhood, qualities of parent-child interactions have a particularly strong and lasting impact on child language, for example predicting child language skills at school entry (e.g., Rodriguez & Tamis-LeMonda, 2011; Rowe & Goldin-Meadow, 2009). The current study examines the possibility of a shift in the relative importance of sensitivity and cognitive stimulation to child vocabulary throughout infancy, from 1 to 3 years of age, as the nature of children’s word-learning shifts with their growing social and cognitive skills (Hollich et al., 2000). Further, we explore whether parents shift their emphases on these dimensions in interactions with children across this period (e.g., Page et al., 2010). We use two different means of measuring parenting: (a) a rating system which rates, on separate but equivalent scales, the quality of parents’ interaction behaviors with children in the sensitive and stimulating dimensions of parenting, and (b) a coding system which categorizes and counts each discrete instance of parenting behaviors during interactions, including those considered sensitive, and those considered stimulating.

Developmental Shifts in Vocabulary Acquisition Requiring Specific Inputs

In contrast to the idea that earlier experiences always matter most for development, or that concurrent experiences are most predictive of child outcomes (e.g., Landry et al., 2001; Rodriguez & Tamis-LeMonda, 2011), one type of specificity is that relationships between parenting inputs and child outcomes vary by developmental stage. That is, the developmental tasks of each period of language development are best supported by certain parental inputs. According to Hollich and colleagues’ (2000) emergentist coalition model for word learning, children’s rapidly growing social and cognitive skills in the second year of life change the processes by which they acquire vocabulary. Around one year of age, the task of learning new words – accurately and permanently attaching a representational label to a category of object or concept (Golinkoff, Mervis, & Hirsh-Pasek, 1994) – is a laborious one that must be heavily scaffolded by caregivers’ contingent responses to children’s attention, interests, and cues so that parents’ labeling of an object or concept is in tune with the child’s attention. At one-year-old, infants are just beginning to develop the social skills to initiate joint attention with a communication partner, relying on the more advanced partner to initiate, maintain, and utilize joint attention to supply new words in a way that supports the child’s learning (e.g., Pruden, Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, & Hennon, 2006). Further, the cognitive skills to learn new words from contextual and linguistic cues begin to develop in the late second and third years of life (Golinkoff, Hirsh-Pasek, Bailey, & Wenger, 1992; Hollich et al., 2000). Thus, according to the emergentist coalition model, the processes of word learning progress from social, to cognitive, then linguistic, requiring differential types of supports from caregivers as children’s primary communication partners (Hollich et al., 2000). Though not central to their theory, Hollich and colleagues (2000) propose an even earlier role, within the first year of life, for affective processes resulting in the experience of inter-subjectivity between infants and caregivers which may prime infants’ learning of the basic premise of language: that one can make reference to something shared. This is in line with Greenbaum’s (2007) idea that early experiences of inter-subjectivity, built upon caregivers’ sensitivity to infant cues, prime the child’s neurologically-based interpersonal skills necessary for language learning, e.g., gaze-following and imitation.

Specificity in Developmental Timing of Parenting Behaviors to Support Child Vocabulary

Given that vocabulary acquisition is supported and constrained through developmental time by children’s skills in various domains – affective, social, cognitive, and linguistic – one may expect that specific parenting behaviors are more or less supportive as children progress through these word-learning phases. The literature on parenting sensitivity and stimulation provides general support for this idea, while leaving some questions unanswered.

Sensitivity

Conceptualization of maternal sensitivity, particularly in infancy, is rooted in attachment theory (Ainsworth, Bell, & Stayton, 1974), which underscores the importance of the early emotional relationship between infants and caregivers, and yields a working definition of sensitivity which describes a parent who is warm, accepting, and responds promptly and contingently to child cues (e.g., Ainsworth et al., 1974; Love et al., 2005; Shin et al., 2008). Because of consistent links between maternal sensitivity and children’s outcomes across domains, sensitivity may be seen as a general precursor to effective parenting to support any child skill – necessary, and perhaps sufficient. But research also shows that specific relations between sensitive behaviors and child language skills may shift over time.

Though there is evidence that toddlers can learn words in a variety of parent-child interactions, including those more and less sensitive to children’s interests, cues, and attention (e.g., Gampe, Liebal, & Tomasello, 2012; Scofield & Behrend, 2011), there is also robust evidence that early sensitivity to children’s affective and attentional states is crucial for producing the episodes of coordinated joint attention in which young children best learn vocabulary (e.g., Farrant & Zubrick, 2012; Rollins, 2003; Tomasello & Farrar, 1986; Tomasello & Todd, 1983). Important here is the role of sensitivity in parents’ parallel talk – use of language to narrate the child’s actions or experience – which requires attuning to the child’s specific states and behaviors and commenting contingently on them so that children can accurately link parents’ words to the internal and external stimuli they perceive. On first glance, there appears a contradiction in the literature regarding whether parents’ sensitivity to child cues, and even the context of joint attention, is necessary for word learning; however, closer examination reveals an age-related shift in the role of parents’ sensitivity and resultant joint attention in vocabulary development. Maternal attunement to and synchrony with children’s emotional and attentional states within the first year of life (3-12 months) produces bouts of coordinated joint attention which predict later symbolic competence, including vocabulary, in the second year of life (Farrant & Zubrick, 2012; Feldman & Greenbaum, 1997; Rollins & Greenwald, 2013). Between 12 and 18 months, length of infant-adult joint attention and adults’ sensitive use of object labeling – in response to child interests within the context joint attention – predict novel word learning and overall vocabulary toward the end of the second year (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2001; Tomasello & Farrar, 1986; Tomasello & Todd, 1983). However, after 18 months, as children’s own skills for social-referencing, imitation, and following others’ attention increase, children become more skilled at learning new words from a variety of contexts (e.g., Gill, Mehta, & Fredenburg, & Bartlett, 2011). Both 18- and 24-month-olds can learn some novel words by simply overhearing them (Gampe, Liebal, & Tomasello, 2012; Scofield & Behrand, 2011), though 24-month olds are more flexible in this ability than 18-month-olds (Callanan, Akhtar, & Sussman, 2014).

Nonetheless, there is still a role for sensitivity to children’s interests and attention in word learning in later toddlerhood and preschool. In a word-learning experiment, 2-year olds learned new words when socially contingent responses were provided, but not when the same cues were provided in a non-contingent way (Roseberry, Hirsh-Pasek, & Golinkoff, 2014). And in naturalistic settings, parents’ contingent imitation of their 24-month-olds’ utterances is beneficial in language development (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2001; Yoder, McCathren, Warren, & Watson, 2001; Girolametto, Weitzman, Wiigs, & Pearce, 1999). Further, even 3-year-old children learn novel words more readily when they are connected to children’s personal interests (Kucirkova, Messer, & Sheehy, 2014). Therefore, although there is always a role for parental sensitivity in children’s vocabulary acquisition (Landry et al., 2001), the social skills that grow markedly after 1 year enable children to learn new words more flexibly (e.g., Gill, Mehta, & Fredenburg, & Bartlett, 2011), possibly making sensitivity less necessary as a support for language learning. Thus, we expect that parental sensitivity will be supportive of children’s vocabulary throughout the first three years, but that its effect may diminish after one year.

Stimulation

In addition to responding sensitively to children’s states and cues, parenting also involves promoting children’s learning through cognitively stimulating interactions. Parents enrich their children’s cognitive and language development by explicitly teaching new words, concepts, and strategies, providing environments replete with stimulating toys, materials, and activities, and supporting exploration of these environments (Martin et al., 2007; Tucker-Drob & Harden, 2012). Like sensitivity, cognitive stimulation is important for children’s language development, as well as later academic skills such as literacy and math (Bradley et al., 2001; Hindman & Morrison, 2012; Hart & Risley, 1995; Melhuish et al., 2008; Crosnoe, Leventhal, Wirth, Pierce, & Pianta, 2010; Rodriguez & Tamis-LeMonda, 2011). In fact, stimulating home environments, characterized by rich language in activities such as shared book reading and scaffolded experiences with manipulative toys, are associated with motor, social, and language development from infancy through adolescence (Bradley et al., 2001; Farah et al., 2008). When parents use complex referential language – about what things are and how they go together – children develop conceptual knowledge, which underpins vocabulary (Weizman & Snow, 2001). Thus, when parents engage children in extended discourse throughout the day, in a variety of activities such as reading, pretend play, and mealtime, children develop larger vocabularies (Dickinson & Tabors, 2001).

Like sensitivity, effects of cognitive stimulation may change throughout development as children gain the cognitive and linguistic skills to learn from more complex language. In the second and third years, children develop the abilities to extend labels to new objects within a category, and understand that words new to them likely apply to a previously unnamed category of objects; they also have the social skills to perceive and apply conventions of speech to the word-learning task (Hollich et al., 2000). Thus, toddlers’ growing skills allow them to make use of caregivers’ complex speech, and take advantage of richer adult vocabulary for their own vocabulary acquisition. In the second year of life, vocabulary is supported by parents’ responsiveness to child’s vocalizations, while in the third year of life, parents’ use of more complex strategies, such as open-ended questions which elicit child language, are most beneficial (McNeil & Fowler, 1999; Dale, Crain-Thoreson, Notari-Syverson, & Cole, 1996).

Thus, both sensitivity and stimulation are dimensions that support child language in early childhood. Yet stimulation can take the form of more directive or controlling behavior, which may be seen as counter to sensitivity. However, the effect of these types of stimulation, and their relationship to sensitivity shift over developmental time (Landry et al., 2001). Thus, there may be a particular role for the intersection of sensitivity and stimulation in support child language.

Bringing Sensitivity and Simulation Together: The Zone of Proximal Development

Vygotsky’s (1978) Sociocultural Theory helps us understand how parental sensitivity and stimulation work together in supporting children’s skill development. Specifically, the zone of proximal development (ZPD) – defined as the space between the level of a child’s current developmental skills (behaviors they can control independently) and the level that he or she can reach with support from a caregiver (Vygtosky, 1978), and considered a driver of development – requires some degree of both sensitivity and stimulation. The ZPD is often framed around problem solving, with the adult supporting the child’s cognitive strategies just beyond the child’s developmental level; however, in order for the ZPD to become actualized, the adult must be sensitive to the child’s current skill level, and respond in an appropriate and stimulating way, tailored to the child’s current abilities and proximal potential (Chak, 2001). For example, parents often respond to infants’ vocalizations and gestures by elaborating on the meaning they think children are conveying, and this sensitively timed, cognitively complex speech predicts child vocabulary (Goldin-Meadow, Goodrich, Sauer, & Iverson, 2007). In this way, adult sensitivity is a necessary prerequisite to providing an optimal ZPD exchange. Although sensitive and stimulating parenting behaviors often occur together, one behavior does not necessitate the other. A parent can be sensitive and warm to their child, without extending their development cognitively; for example, caregivers may simply imitate their child’s vocalizations, babbling and smiling in response to a child’s babble, without verbally interpreting or elaborating on the child’s vocal cue. Conversely, a parent can be actively involved in promoting a child’s cognitive competencies, but do so in an insensitive way that neglects the child’s needs for warmth, as well as his or her cues or pacing needs; we see this in caregivers’ use of “drilling” or “quizzing” of young children, or the frequent presentation of new stimuli, rather than attempts to support the child’s sustained attention on objects of their own interest. Optimally, parents will combine sensitive and stimulating behaviors together in everyday parent-child interactions that support children’s development in a variety of ways. In fact, it may be that sensitivity is a necessary precursor to positive effects of stimulation. Thus, we question whether parental sensitivity moderates the effects of stimulation on children’s language development.

Change within Parents over Time

Given that optimal support of children’s vocabulary development likely requires timely shifts in parenting behaviors – from a focus on the affective exchanges of early infancy, to sensitive responses to a variety of child cues, to more cognitively and linguistically complex inputs (Hollich et al., 2000) – we may expect parents to change in response to children, making timely trade-offs in their interactional emphases. There is evidence that parenting behaviors change over time, especially through early childhood (Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005; Holden & Miller, 1999; Rodriguez & Tamis-LeMonda, 2011). In a meta-analysis of 56 studies examining parental change, Holden and Miller (1999) determined that parents demonstrate relative stability but absolute differences in parenting behaviors; that is, parents stay stable in comparison to other parents, but change in comparison to themselves. Importantly, of all parenting behaviors examined, stimulation demonstrated the largest mean difference from infancy through middle childhood, with an effect size d =.52. Overall, parents were least stable when their children were infants, and most stable when children were school-age (Holden & Miller, 1999). Similarly, Dallaire and Weinraub (2005) found that, while parents who were sensitive and stimulating in infancy were likely to be so later in childhood, these behaviors were not continuous, as parents overall became more stimulating as their children aged (Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005). Importantly, parental sensitivity and stimulation are moderately correlated over time (Holden & Miller, 1999), but the methodologies used by most studies do not allow examination of whether there might be trade-offs in these dimensions.

The mean level changes in parenting behaviors, coupled with relative stability in rank order, support Darling and Sternberg’s (1993) suggestion that parenting style and parenting behavior are two distinct concepts. They posit that parenting style remains stable while specific parenting behaviors change in response to child development. This is consistent with the idea that parenting dimensions (as well as other human behaviors) operate at multiple levels, an absolute level of behavioral form (the “etic” level; Lindahl, 2001), and a functional level related to the meaning or purpose of the behavior (the “emic” level) which is only revealed in specific contexts (Bornstein, 1995). Thus, it may be that at the broad level of meaning, sensitive parents stay sensitive to their children’s growing needs by changing their specific behaviors. For example, the developmental needs of infants for attention and affection to form a secure attachment (Ainsworth et al., 1974) evoke parental responsivity and joint attention; the developmental needs of older infants and toddlers to explore the environment and develop independence demand from parents the encouragement to explore independently and support to regulate behavior for safety. The moderate, rather than strong, correlations in parents’ earlier and later ratings of sensitive and stimulating behaviors indicate a good deal of intra-individual change, for example, as parents become more stimulating as children grow (Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005). However, no studies have explicitly examined whether parents make trade-offs in their communicative interactions with children – at the level of discrete behaviors emphasizing form –between emphases on sensitivity versus stimulation. Importantly, the degree to which parents modify behaviors in response to children may vary by socio-economic status; Lawrence and Shipley (1996) found middle-, but not working-class, parents increased their language input as children grew. Thus, it may be useful to examine changes in parenting, and changing effects of parenting on children’s development, specifically in low-income samples.

This change in stimulation may be seen as a form of sensitivity to children’s growing needs and competencies, and the abilities of parents to make these shifts may be an important aspect of sensitivity itself. We wonder whether there is a trade-off parents must make, in their moment-to-moment interactions with children, between focusing on responding to children’s cues and interests, and providing stimulation to help the child move beyond the focus of his or her current interests or attention. This question demands an examination of parenting behaviors as mutually exclusive in order to detect whether they are in competition with each other.

Methodological Considerations: Rating versus Categorization of Parenting Behaviors

While sensitivity and stimulation are sometimes grouped together as part of “supportive parenting” (e.g., Rodriguez & Tamis-LeMonda, 2011), many studies examine these dimensions separately, often measuring just one or the other; on the other hand, most measures of caregiving quality in childcare settings, designed to assess the interactions which support children’s development, assess both sensitivity and stimulation as distinct dimensions (Halle et al., 2011). Further, most studies that measure these dimensions using observations of parent-child interactions use rating scales to assess the relative quality of these dimensions (e.g., Ayoub, Vallotton, & Mastergeorge, 2011; Else-Quest, Clark, & Owen, 2011). Measuring parenting dimensions on separate but equivalent scales is necessary to compare their specific effects on children’s development. In general, global ratings and aggregate scores – at the emic level of behavioral meaning – better capture similarities between individuals and consistency within individuals over time. On the other hand, coding of discrete or momentary behaviors – with an emphasis on the etic level of form – is more likely to capture differences between participants, as well as within participants over time, but may be less representative of stable qualities (Cairns & Green, 1979). Further, methods that examine sensitivity and stimulation as independent parenting dimensions, each rated on separate scales, may not distinguish the two dimensions sufficiently to elucidate the trade-offs that parents may make in their communicative interactions with children; that is, the definitions of low and high quality on rating scales may implicitly or explicitly be defined to include elements of both dimensions. Instead, coding discrete behaviors that align with these broader dimensions may be more effective to elucidate change over time in parents’ actual behaviors, as well detect trade-offs in emphases between these two dimensions.

Studies of parent and child communication and child language often examine the features of language microanalytically – on an utterance by utterance basis – categorizing each utterance as serving certain communicative purposes (e.g., Ninio, Snow, Pan, & Rollins, 1994; Rollins, 2003). By categorizing each communicative turn between parents and children into mutually exclusive categories – rather than rating an entire lengthy interaction as high or low on a particular quality – the trade-offs that parents make with children become more apparent, and may reveal child age-related changes in parents’ sensitive and stimulating behaviors. We wonder whether there is a trade-off parents make in their communicative interactions with young children between behaviors that are primarily sensitive responses and those that are cognitively stimulating, and whether these can be detected using a microanalytic coding system of parents’ and children’s communicative turns.

Current Study

Different ways of measuring maternal sensitivity and stimulation are necessary to address both change over time in behaviors and changes in their effects on child vocabulary. By examining maternal sensitivity and stimulation, using both a rating system and a categorical coding system, at multiple points during infancy and toddlerhood, we explore these two parenting behaviors over time to determine how each may uniquely contribute to children’s early vocabulary development. A focus on low-income, high-need families increases the relevance of findings for targeted interventions focusing on parental supports for early language development. We ask the following questions:

1) What is the relative importance of mothers’ sensitivity and cognitive stimulation throughout infancy and toddlerhood to children’s vocabulary development?

2) Does sensitivity moderate the effect of stimulation such that sensitivity is a necessary precursor to a positive effect of stimulation on child vocabulary?

2) Do mothers change their interactional emphases throughout infancy and toddlerhood?

Methods

Dataset and Sample

We use the New England sample (N=146) of the national Early Head Start Research and Evaluation (EHSRE) dataset, which includes all variables available in the national dataset, and richer data on children’s expressive language, including a measure of expressed vocabulary, and additional coding of mother-child interactions including discrete behaviors which can be categorized as sensitive or stimulating. The EHSRE is a prospective, longitudinal study in which half of families were randomly assigned to receive the Early Head Start (EHS) intervention, and half were assigned to a comparison group not offered EHS services. For eligibility, families must have (a) had an income near or below the federal poverty level; (b) had a child under 12 months old; and (c) not previously participated in an early intervention program similar to EHS. In the New England site, 77.4% of the children were Caucasian, 14.4% were African American, 4.8% Hispanic, and 3.4% other. Ninety seven percent (97%) of families spoke English as their primary language at home, and 1% spoke English well as a second language. The 2% of families (n = 3) who spoke limited English were excluded from the microanalytic coding of maternal behavior.

Procedures

Four waves of data are used in the current study. The baseline wave was collected when families entered the study between the time the mother was pregnant with the focal child and when the child was 12 months old. Waves 1 through 3 were collected when children were around 14, 24, and 36 months. Demographic information including mother education, age, employment status, household income, receipt of welfare, and family structure was collected via interview at baseline. Data collection at subsequent waves included child development assessments, interviews with mothers, and observations of mother-child interactions in the home (see Love et al., 2005 for methods and procedures).

During home visits, children and mothers participated in the 3-bag task, a 10-minute semi-structured play activity (Vandell, 1979). Mothers and children were given three bags, each containing an age-appropriate set of toys, and were told that they had 10 minutes to play with the toys. Play sessions were videotaped and later coded. In the New England site, investigators transcribed and coded these interactions for additional information on children’s and mothers’ language use, and mothers’ specific interaction behaviors.

Measures and Variables

Child productive vocabulary

All language in the mother-child interaction during the 3-bag task was transcribed using the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES; MacWhinney, 2000; see Pan, Rowe, Spier, & Tamis-LeMonda, 2004 for further description). All transcripts were checked for reliability, and corrected as needed, by a second transcriber or by the same transcriber two weeks after initial transcription. The Child Language Analysis (CLAN) software was used to summarize children’s expressed vocabulary during each observation, defined as the number of unique words the child spoke; e.g., “dog” and “cat” are two vocabulary words, but “dog” and “dogs” are considered one vocabulary word. Pan and colleagues (2004) found this observational measure of vocabulary highly correlated with mothers’ reports of child vocabulary via the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory.

Parenting sensitivity and stimulation

We use two different ways of measuring each dimension of parenting during the same set of mother-child interactions described above. First, we use ratings of mothers’ sensitivity and stimulation applied to the play session as part of the national EHSRE study. Then, we use a coding system categorizing each communicative turn into one mutually exclusive category, capturing the communicative function of each turn.

Rating scales

To address our first research question, we needed to compare the effects of two different predictors – sensitivity and stimulation – to one another. To do this, we needed an observational measure in which the values would have comparable meanings; that is, measured in the same way and on the same scale, but independent of one another. Thus, we used the rating system from the national EHSRE dataset which rated mothers’ sensitivity and cognitive stimulation on separate but equivalent scales. Because the scales were independent, mothers could obtain the maximum or minimum score on both. The sensitivity scale measures the mothers’ sensitivity to child cues, which includes her ability to accurately read and adequately respond the child’s behaviors, needs, moods, and interests. The cognitive stimulation scale measures mothers’ intentional teaching efforts appropriate to the child’s age and developmental level. Each of these interaction qualities was rated on a 1 to 7 scale in which 1 indicates very few and poor quality instances of the dimension, and 7 indicates consistent and high quality instances. Before coding independently, raters obtained 85% agreement within one point on all scales; reliability checks were also completed on 15% of rated episodes, in which agreement was above 90% on average. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation for child and mother characteristics, child language, and ratings of mothers’ parenting at each wave.

| Variables | Wave 1 (n = 125) |

Wave 2 (n = 113) |

Wave 3 (n = 107) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Age in Months | 14.57 (1.22) |

24.57 (1.23) |

37.03 (1.77) |

| Child Communicative Tokens | 4.99 (9.26) |

87.81 (67.69) |

190.88 (97.09) |

| Child Expressed Vocabulary | 2.67 (4.14) |

37.63 (24.72) |

73.17 (27.15) |

| Maternal Sensitivity Rating | 5.15 (1.23) |

5.06 (1.10) |

4.95 (1.08) |

| Maternal Cognitive Stimulation Rating | 4.12 (1.24) |

4.42 (1.25) |

3.93 (1.21) |

Coding system

To examine whether parenting behavior itself changes over time, we needed a measure of behavior that carried the same absolute meaning from one wave to the next. Further, to determine if there is a trade-off in mothers’ use of two different dimensions – sensitivity which focuses on responding to infants’ own attention, states, and interests, and stimulation which can be more directive and focuses on expanding the child’s attention and interests – we needed an observational measure in which there was a forced choice between behaviors considered primarily sensitive and primarily stimulating. We applied a microanalytic coding system to the transcripts of mother-child interaction, integrating the codes into the transcripts using the Child Language Data Exchange System described above (CHILDES; MacWhinney, 2000), such that for every turn in the interaction – with or without language – mothers’ interaction behaviors were coded as one mutually exclusive, categorical behavior.

The coding system captured mothers’ interaction behaviors turn-by-turn using an adapted version of the Themes and Emotions Coding System (Ayoub, Raya, & Russell, 2000) which was created to examine discrete caregiver and child behaviors in each interactional turn, with or without language. The coding system contained both sensitive behaviors and cognitively stimulating behaviors; it also contained many other behaviors which fit into other commonly studied parenting dimensions including positive and negative regard, and intrusiveness. Sensitive behaviors included those such as attending to and acknowledging child activities, interpreting the child’s unspoken need or desire, and imitating the child’s behaviors or vocalizations. Cognitively stimulating behaviors included teaching behaviors such as defining, explaining, and testing the child’s knowledge. Table 2 provides descriptions of each sensitive or stimulating behavior, and descriptive statistics for their frequencies expressed as rate per 10-minutes. Reliability of the coding scheme was established using Cohen’s Kappa (Bakeman & Gottman, 1987), and was 0.88 on average. To make the most direct comparison between dimensions, we use the percent of behaviors within each conceptual category; for example, we added the frequencies of each code considered to stimulating for a total frequency of stimulating behaviors, then divided these by the total frequency of all codes, or maternal communicative turns. Because the codes were mutually exclusive, and thus not independent of one another, there could be a tendency for each set of codes (sensitivity codes, stimulation codes) to be negatively correlated; however, there were many other codes not included in either the sensitivity or stimulation set, reducing the potential colinearity of these two constructs. The full coding system with the codes not considered sensitive or stimulating is available from the authors.

Table 2.

Mothers’ sensitive and stimulating behaviors at each wave expressed as rate per 10 minutes.

| Mean Rate (SD), Min-Max | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Definition | 14 Months (n = 79) |

24 Months (n = 74) |

36 Months (n = 73) |

| Sensitive Behaviors | ||||

| Acknowledge | Nonverbal acknowledgement of child |

8.64 (6.15) 0.00 – 27.58 |

8.74 (5.30) 0.61 – 28.41 |

8.86 (5.10) 0.00 – 31.25 |

| Answer | Responds to child’s question | -- | -- | 3.89 (11.80) 0.00 – 100.00 |

| Choice | Indicate that child has a choice |

0.25 (1.08) 0.00 – 9.14 |

0.42 (0.87) 0.00 – 3.97 |

0.24 (0.65) 0.00 – 4.17 |

| Imitate | Imitates child’s behavior or vocalization |

0.97 (2.68) 0.00 – 22.68 |

2.30 (2.12) 0.00 – 11.30 |

2.56 (2.46) 0.00 – 11.35 |

| Interpretation | Verbalizes child’s unspoken needs or wants |

4.22 (3.25) 0.00 – 15.30 |

3.88 (3.13) 0.00 – 11.94 |

3.63 (2.96) 0.00 – 13.22 |

| Perform Requested Action |

Responds to child’s request to do something |

-- | -- | 0.42 (0.73) 0.00 – 4.13 |

| Positive Comment |

Positive comment about child’s behavior or performance |

1.35 (1.85) 0.00 – 8.00 |

1.54 (1.90) 0.00 – 7.69 |

2.05 (2.18) 0.00 – 9.32 |

| Praise | Positive comment on child’s characteristics |

0.42 (0.96) 0.00 – 5.02 |

0.64 (1.21) 0.00 – 4.92 |

0.06 (0.22) 0.00 – 1.16 |

| Share Engagement |

Includes self in child’s activity |

3.50 (3.34) 0.00 – 17.08 |

3.85 (2.33) 0.00 – 11.48 |

3.81 (3.17) 0.00 – 12.92 |

| Sooth | Verbal or non-verbal attempts to comfort or calm child |

0.45 (1.47) 0.00 – 11.93 |

0.29 (1.17) 0.00 – 8.73 |

0.01 (0.09) 0.00 – 0.54 |

| Cognitively Stimulating Behaviors | ||||

| Correct | Corrects child’s incorrect statement or behavior |

1.26 (2.82) 0.00 – 20.90 |

2.01 (2.18) 0.00 – 9.50 |

3.45 (2.85) 0.00 – 15.25 |

| Define | Labels or gives information about how an object is used |

10.23 (5.24) 0.00 – 23.31 |

12.06 (6.01) 1.77 – 25.90 |

12.13 (7.28) 0.83 – 39.60 |

| Attention | Direct child’s attention | 18.60 (10.41) 0.00 – 44.60 |

8.00 (5.41) 0.00 – 24.32 |

2.28 (2.73) 0.00 – 12.90 |

| Explain | Explains, models, or demonstrates a task or object use |

5.51 (5.65) 0.00 – 27.17 |

6.55 (4.84) 000 – 22.28 |

5.25 (3.70) 0.00 – 15.63 |

| Inform | Provides general information not related to task |

0.53 (0.65) 0.00 – 3.00 |

0.59 (0.96) 0.00 – 4.93 |

1.15 (1.38) 0.00 – 8.28 |

| Onomatopoeia | Makes sound effect for a toy | 1.09 (1.87) 0.00 – 7.30 |

0.74 (1.86) 0.00 – 11.49 |

0.29 (0.75) 0.00 – 4.48 |

| Question | Asks question other than request or knowledge check |

5.40 (5.97) 0.00 – 32.61 |

7.90 (5.68) 1.59 – 26.54 |

6.69 (4.53) 0.00 – 17.02 |

| Read Text | Reads from text, not including additional information |

0.80 (2.30) 0.00 – 32.61 |

3.83 (5.35) 0.00 – 21.92 |

8.50 (9.37) 0.00 – 31.71 |

| Request | Mother engages child through request |

4.72 (3.70) 0.00 – 16.06 |

5.84 (4.44) 0.00 – 20.00 |

5.16 (3.73) 0.00 – 19.11 |

| Self-Reference | Comments on own actions or states |

1.14 (1.22) 0.00 – 5.00 |

1.85 (1.96) 0.00 – 9.2 |

2.29 (2.02) 0.00 – 9.70 |

| Test Knowledge |

Checks child’s knowledge by asking question |

5.10 (4.00) 0.00 – 14.08 |

8.53 (6.36) 0.00 – 33.75 |

7.44 (5.57) 0.00 – 31.61 |

| Total Maternal Communicative Turns | 179.82 (69.63) 25.00 – 331.00 |

162.24 (45.29) 67.00 – 274.00 |

148.00 (38.72) 59.00 – 248.00 |

|

Child age

Child age was measured as the difference between child birth date and the date of data collection at each wave. For longitudinal analysis, we center age at 14 months.

Child gender

Child gender is effect coded such that boy = 1 and girl = −1 (49%).

Maternal risk composite

Demographic risks were measured at baseline, and each was coded present or absent, including teen parenting (1 = mother < 20 years at child’s birth; 24%), low education (1 = < high school education; 28%), government assistance (1 = receiving TANF; 36%), unemployment (1 = mother not employed, not in school; 68%), and single parenting (1 = no adult male in household; 13%). A composite was created, indicating families who had 0 to 2 risks (51%), 3 risks (29%), or 4 to 5 risks (20%).

EHS assignment

Each family’s randomly determined assignment to the Early Head Start intervention was coded as a binary variable (1 = offered EHS intervention; 51%).

Analyses and Results

Analysis of Attrition and Approach to Missing Data

In the EHSRE study, there was attrition at each wave after baseline; in the New England sample, 73% of the sample was retained to Wave 3, meaning they provided at least some data at each wave. For the 3-bag task specifically, the majority of families participated at Wave 1, 73% (n = 106) participated at Wave 1, 63% at Wave 2 (n = 92), and 50% at Wave 3 (n = 73). To test for selective attrition in the New England sample, we compared demographics of families who participated in Waves 1 through 3 to the whole sample at baseline; no significant differences were identified. To detect potential differences between those who did and did not participate in the 3-bag task at each wave, we compared these two groups on each risk indicator, and the cumulative risk index, measured as baseline or Wave 1. The only difference between those who did and did not participate in the 3-bag task at Wave 1 was the number of moves the family had had prior to that wave; those who did not participate had 0.68 moves, while those who did participate had 1.17 moves on average (t = 2.814, df = 100, p < .01). The only difference at Wave 2 was family income, measured as percent of poverty line at the baseline measure; families who did not participate had a mean of 62%, while families who did participate had a mean of 82% (t = 2.782, df = 137, p < .01). There were no differences in baseline family demographics or risks between those who did and did not participate in the 3-bag task at Wave 3; importantly, for those who did not participate in the task at Wave 3, there were no differences in parenting qualities (sensitivity, stimulation) at Waves 1 or 2.

We use multi-level models (SPSS MIXED), with full information maximum likelihood estimation (FMLE). This allows all available data to be used in estimating models, even when participants have some missing data (Singer & Willett, 2003). This method has been shown to be equivalent to, or more accurate than, multiple imputation of missing data (Larsen, 2011).

Changing Effects of Sensitivity and Stimulation

To answer our question on the relative importance of maternal sensitivity and stimulation for child vocabulary throughout the second and third years of life, we fit a series of multi-level growth models predicting expressed vocabulary, nesting observations within children over time. We used Wave as the index of nested observations, child age as a predictor, and controlled for child gender, maternal risk, and EHS assignment; we allowed the intercept to vary across individuals (random effect), but constrained the effects of child age, using it as only as a fixed effect. We added the sensitivity and cognitive stimulation ratings, measured at each wave, as time-varying predictors (fixed effects). We tested whether stimulation and sensitivity simultaneously affected the level of children’s expressive vocabulary at each wave between 14 and 36 months (Table 3, Model A). Next we interacted child age with each parenting dimension to test whether effects of these dimensions on vocabulary changed over time (Model B). Then, we fit a parsimonious model, deleting non-significant interactions (Model C).

Table 3.

Results of fitted models for the effects of maternal sensitivity and cognitive stimulation on children’s language development from 14 to 36 months (n = 120 children).

| A | B | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Fixed Effects | Effects of Time- Varying Parenting Dimensions |

Change in Effects of Time-Varying Parenting Dimensions |

Parsimonious Effects of Time-Varying Parenting Dimensions |

Interaction Between Time-Varying Parenting Dimensions |

| Intercept (at age 14m) | 2.56 (1.98) |

2.32 (1.95) |

2.10 (1.95) |

2.29 (2.18) |

| Child Sex (Boy = 1, Girl = −1) | −3.66*

(1.47) |

−3.57*

(1.46) |

−3.64*

(1.47) |

−3.62*

(1.48) |

| Maternal Risk Composite (Centered) | 1.57 (1.97) |

1.76 (1.96) |

2.04 (1.96) |

2.04 (1.98) |

| EHS (Program = 1, Control = 0) | 1.46 (1.53) |

1.83 (1.52) |

1.67 (1.52) |

1.67 (1.53) |

| Growth (child age in months) | 3.22***

(0.12) |

3.29***

(0.12) |

3.30***

(0.12) |

3.28***

(0.14) |

| Time-Varying Sensitivity (z-score) | 4.63**

(1.68) |

2.81 (2.22) |

4.76**

(1.63) |

4.73**

(1.79) |

| Change in Effect of Sensitivity (sensitivity*child age) | 0.21 (0.16) |

|||

| Time-Varying Stimulation (z-score) | 3.50*

(1.58) |

0.32 (2.14) |

−0.80 (1.96) |

−0.81 (2.02) |

| Change in Effect of Stimulation (stimulation*child age) | 0.32*

(0.16) |

0.45***

(0.13) |

0.45**

(0.13) |

|

| Moderation of Stimulation by Sensitivity (sensitivity*stimulation) | 0.03 (0.12) |

|||

|

| ||||

| Variance | ||||

| Between Child Intercept | 91.03** | 95.01** | 97.37** | 98.37** |

| Within Child | 260.69*** | 241.76*** | 241.22*** | 243.21*** |

|

| ||||

| Model Fit | ||||

| -2LL | 1986.61 | 1976.79 | 1976.70 | 1976.69 |

~ p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

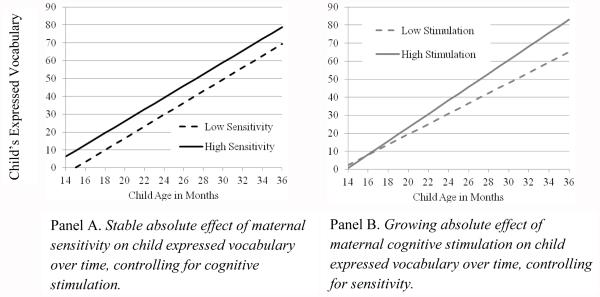

As seen in Model A of Table 3, both sensitivity and cognitive stimulation simultaneously affected children’s expressed vocabulary from infancy through toddlerhood, with sensitivity having a somewhat stronger effect than cognitive stimulation overall. However, the effect of cognitive stimulation increased over time, whereas the effect of sensitivity on the number of unique words children produced remained constant; in Model B, the interaction between time-varying sensitivity and child age was not significant, whereas there was an interaction between cognitive stimulation and child age. The fitted results of Model C are depicted in Figure 1. Maternal sensitivity (depicted in Panel A as one SD higher and lower than average) had a substantial and steady effect on the number of unique words children spoke during the observed interaction. On the other hand, as seen in Panel B, mothers’ cognitive stimulation had no impact on children’s expressed vocabulary in infancy, but its effect increased over time, eventually growing larger than that of sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Change in effects of maternal sensitivity and cognitive stimulation on level of children’s expressed vocabulary from 14 to 36 months.

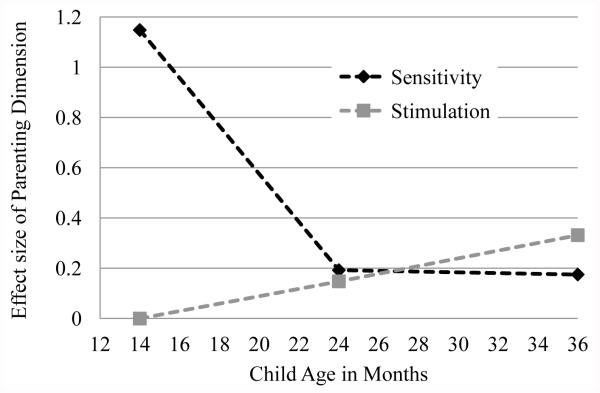

Our measure of child expressive vocabulary for this analysis was the absolute number of unique words the child spoke during the interaction, and the variation in this expressed vocabulary increased rapidly between the first and third waves (see the standard deviations for this variable at each wave in Table 2). Thus, the absolute effect of maternal sensitivity on child vocabulary remained the same over time (as seen in the Table Model C), resulting in about 5 more unique words spoken by the child at each observation. However, the effect of maternal sensitivity relative to the variation (i.e., standard deviation) in children’s expressive vocabulary diminished over time; thus, we estimated the effect sizes for maternal sensitivity and stimulation on children’s expressed vocabulary at each wave. As seen in Figure 2, the effects of one standard deviation in each parenting dimension on children’s expressive vocabulary changes substantially throughout toddlerhood. At 14 months, maternal sensitivity had a large estimated effect of 1.15 standard deviations in child vocabulary while cognitive stimulation had no effect. By 24 months, the estimated effects of sensitivity (0.19) and stimulation (0.15) were relatively small and similar in size. By 36 months, cognitive stimulation had a moderate effect (0.33), larger than the effect of sensitivity (0.15).

Figure 2.

Change in estimated effect sizes of maternal sensitivity and cognitive stimulation on children’s expressed vocabulary from 14 to 36 months.

Moderation of Stimulation by Sensitivity

To address our question on whether maternal sensitivity is a necessary condition in order for maternal stimulation to support children’s vocabulary, we fit a 4th growth model to test whether sensitivity moderated the effect of stimulation on child vocabulary. Using the parsimonious Model C from the last analyses as a baseline model (Table 3), we added an interaction between time-varying sensitivity and time-varying stimulation. We also tested the possibility that there was a change in moderation over time by testing a 3-way interaction between sensitivity, stimulation, and child age; further, we tested whether early sensitivity (at 14 months) might moderate the effect of time-varying stimulation. These models produced consistently null results, indicating that sensitivity does not moderate the effect of stimulation on young children’s vocabulary (see Model D).

Change in Parenting Behaviors Over Time

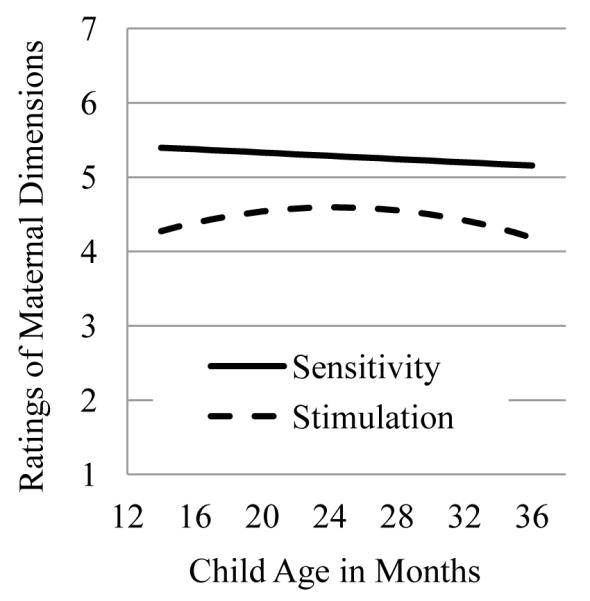

Findings from our first two questions indicate that maternal sensitivity and cognitive stimulation have different and independent effects on children’s vocabulary over time, and that cognitive stimulation becomes more important throughout toddlerhood. However, this does not indicate whether parenting behaviors themselves actually change over time to meet children’s needs. Our expectation was that, if there was evidence of change, we would see an increase specifically in mothers’ cognitive stimulation, consistent with the literature (e.g., Holden & Miller, 1999) and with the idea that children’s advancing skills would draw more stimulation from their mothers. We used two strategies to address this question. First, we tested whether the rating system used to measure mothers’ sensitivity and stimulation could reveal changes in the mean levels of these dimensions over time. Given that these ratings are global, encompassing many behaviors, and their definitions include an element of “developmental appropriateness” which implies shifts in more specific behaviors, we did not expect to see meaningful differences in these ratings of parenting dimensions over time. Still, we examined the possibility of change using multi-level growth models to examine change in maternal sensitivity and stimulation using child age as a primary predictor, with observations (Waves) nested within mothers over time; we allowed the intercept to vary across mothers, but constrained the effect of child age (fixed effect only). We controlled for Maternal Risk and EHS program assignment. As seen in the first model in Table 4, there was little indication of change in sensitivity over time; the linear change affected by child age was small and significant only at the p < .10 level. However, as seen in the second model, maternal cognitive stimulation did change over time, growing quadratically with child age such that mothers’ stimulation increased from 14 months through 24 months, then began to decline (see Figure 3).

Table 4.

Results of fitted multi-level models for change in mothers’ levels of sensitivity and stimulation from child age 14 to 36 months (n = 103 children).

| Fixed Effects | Sensitivity | Stimulation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercept (at child age 14m) | 5.689*** | (0.457) | 4.623*** | (0.729) |

| Maternal Risk Composite | −0.292** | (0.108) | −0.349** | (0.130) |

| EHS (Program = 1, Control = -1) | −0.217* | (0.084) | −0.127 | (0.100) |

| Linear Change (child age in months) | −0.011~ | (0.006) | 0.062* | (0.024) |

| Acceleration (child age*child age) | -- | -- | −0.003** | (0.001) |

|

| ||||

| Variance | ||||

| Between Mother Intercept | 0.164 | 0.466 | ||

| Within Mother | 0.737 | 0.845 | ||

| Covariance | 0.367 | 0.585 | ||

|

| ||||

| Model Fit | ||||

| −2LL | 705.003 | 751.472 | ||

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Figure 3.

Change in ratings of maternal sensitivity and cognitive stimulation from 14 to 36 months.

To follow these initial findings of significant changes in levels of the whole sample, we utilized the rating scales to assess mothers’ rank order stability over time, relative to others, and the possibility of competition between sensitivity and stimulation as seen in negative correlations between these variables within waves. As seen in Table 5, mothers were only somewhat stable from one wave to the next, with moderate correlations between ratings of each dimension in adjacent waves ranging from 0.43 to 0.60; there appears to be greater rank order stability in stimulation than in sensitivity, particularly between 24 and 36 months, when stimulation overall was declining. Instead of seeing evidence of competition between sensitivity and stimulation, there is evidence that these dimensions are strongly positively related, with correlations within waves ranging from 0.47 to 0.81; these are stronger correlations than the within-dimension, between-wave correlations.

Table 5.

Results of Pearson correlations (2-tailed) for the relationships between ratings of mothers’ sensitivity and cognitive stimulation across waves.

| Sensitivity 24m |

Sensitivity 36m |

Stimulation 14m |

Stimulation 24m |

Stimulation 36m |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity 14m |

.45***

n=82 |

.39**

n=64 |

.47***

n=100 |

.45***

n=82 |

.25*

n=64 |

| Sensitivity 24m |

.43***

n=63 |

.43***

n=82 |

.81***

n=92 |

.63***

n=63 |

|

| Sensitivity 36m |

.37**

n=64 |

.47***

n=63 |

.62***

n=73 |

||

| Stimulation 14m |

.43***

n=82 |

.43***

n=64 |

|||

| Stimulation 24m |

.60***

n=63 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Second, we used the microanalytic coding system which measured the frequency and percent of mothers’ specific behaviors considered sensitive or stimulating. These more specific parenting behaviors are defined in such a way that they have the same absolute meaning at each wave, thus we expected to see change over time, and perhaps a trade-off reducing the percent of behaviors defined as primarily sensitive in favor of those that are primarily stimulating. We fit a series of multi-level models for each maternal behavior, using the data collection wave to estimate the effects of child age. Further, we controlled for children’s communication tokens because we expected that the frequency of children’s communicative cues would affect the number of maternal behaviors that are in response to children’s cues, thus potentially systematically affecting our estimates of mothers’ sensitive, but not necessarily their stimulating, behaviors. Results of each model (Table 6) revealed many significant differences in maternal behaviors when children were 24 and 36 months compared to behaviors when children were 14 months. Given the number of separate outcomes (19), and related number of tests performed here, increasing the family-wise error, we interpret only those significant at the p < .01 level.

Table 6.

Results of fitted multi-level models for percents of mutually exclusive maternal behaviors during a 10-minute interaction, controlling for child communicative tokens (n = 99).

| Maternal Behavior |

Level at 14 months (Intercept) |

Difference between 14 and 24 months |

Difference between 14 and 36 months |

Child Vocal Communication (z-score) |

−2LL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive Maternal Behaviors | |||||

|

| |||||

| Acknowledge | 8.5507***

(0.6203) |

−1.0293 (0.9834) |

−2.8512*

(1.3416) |

1.6638**

(0.5790) |

1289.53 |

| Comment on Choice |

0.2530*

(0.1249) |

0.2148 (0.1750) |

−0.1814 (0.2282) |

0.0042 (0.0930) |

545.02 |

| Imitate | 1.3056***

(0.3362) |

0.8684~

(0.4598) |

0.8100 (0.6086) | 0.4221~

(0.2529) |

946.31 |

| Interpret | 4.4291***

(0.4246) |

−1.0343~

(0.5641) |

−1.0412 (0.7577) |

0.2297 (0.3209) |

1040.21 |

| Positive Comment | 1.3040***

(0.2800) |

0.2502 (0.3729) |

0.7969 (0.4986) |

−0.0598 (0.2119) |

877.53 |

| Praise | 0.3898**

(0.1263) |

0.2440 (0.1736) |

−0.2834 (0.2290) |

−0.0413 (0.0948) |

548.81 |

| Share Engagement |

4.1377***

(0.4158) |

−0.2582 (0.5337) |

−1.1149 (0.7270) |

0.7916*

(0.3132) |

1030.61 |

| Sooth | 0.4689**

(0.1610) |

−0.1177 (0.2232) |

−0.4831 (0.2931) |

0.0265 (0.1206) |

647.87 |

|

| |||||

| Stimulating Maternal Behaviors | |||||

|

| |||||

| Correct | 0.8828*

(0.3702) |

1.2161**

(0.4494) |

3.0457***

(0.6225) |

−0.4690~

(0.2735) |

981.27 |

| Define | 10.9686***

(0.8752) |

1.2573 (1.1508) |

0.1704 (1.5528) |

0.9319 (0.6613) |

1333.57 |

| Direct Attention | 18.3851***

(1.0083) |

−10.4684***

(1.3888) |

−15.8169***

(1.8306) |

−0.2731 (0.7568) |

1392.42 |

| Explain | 5.5385***

(0.6784) |

0.7509 (0.9066) |

−0.3789 (1.2144) |

0.0382 (0.5125) |

1230.62 |

| Inform | 0.5439***

(0.1421) |

0.0337 (0.1911) |

0.5886*

(0.2551) |

0.0143 (0.1072) |

566.02 |

| Onomatopoeia | 1.1413***

(0.1943) |

−0.5936*

(0.2583) |

−0.9113*

(0.3483) |

0.0673 (0.1470) |

719.22 |

| Question | 5.7080***

(0.7675) |

2.7482**

(1.0286) |

0.5898 (1.3759) |

0.3546 (0.5797) |

1280.82 |

| Read Text | −0.8129 (0.8820) |

4.6297***

(1.1777) |

11.5465***

(1.5781) |

−2.0891**

(0.6665) |

1337.17 |

| Request | 4.9026***

(0.5686) |

0.8205 (0.7693) |

0.0043 (1.0241) |

0.2158 (0.4289) |

1159.31 |

| Self Reference | 1.2055***

(0.2411) |

0.4927 (0.3124) |

0.9617*

(0.4240) |

0.1117 (0.1819) |

809.72 |

| Test Knowledge | 4.7261***

(0.7692) |

4.2127***

(1.0647) |

3.1525*

(1.39926) |

−0.4202 (0.5762) |

1282.70 |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

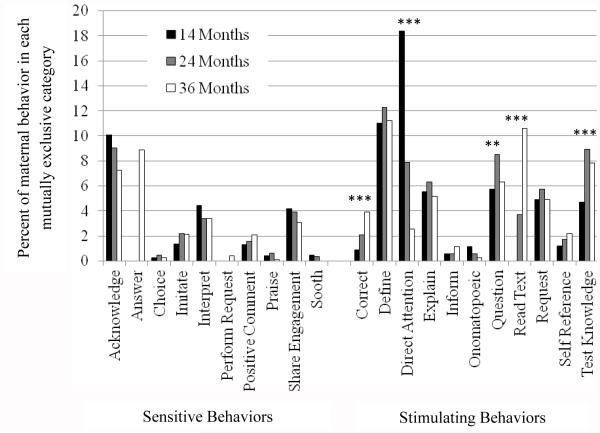

Figure 4 displays the estimated marginal means for the percent of each behavior at each wave, controlling for child tokens. There were few observed changes in maternal sensitive behaviors, and none at the p < .01 level. The sensitive behavior of answering the child only appeared at 36 months, thus it was a meaningful change, but could not be analyzed statistically. There were some cognitively stimulating behaviors that were also highest in infancy, including directing the child’s attention and onomatopoeias. There were also a number of cognitively stimulating behaviors that increased with child age including correcting, questioning, reading text, and testing the child’s knowledge. Questioning the child and testing the child’s knowledge were highest at 24 months, and reduced somewhat by three years.

Figure 4.

Estimated marginal means for the percents of mothers’ mutually exclusive sensitive and stimulating behaviors when children are 14, 24, and 36 months old. ** p < .01, *** p < .001

These results did not confirm our expectation of a trade-off between sensitive behaviors, which are focused on responding to children’s cues and needs, and stimulating behaviors, which are focused on expanding the child’s attention and interests. However, it did reveal a number of changes in specific maternal behaviors within each category indicating an adaptation to the child’s changing needs, notably a dramatic decrease in the stimulating behavior of directing the child’s attention, and an increase in the sensitive behavior of answering the child directly, along with increases in other stimulating behaviors including correcting, informing, questioning, reading text, self-reflective talk, and testing the child’s knowledge.

Discussion

This study tested specificity in the timing of two important parenting dimensions that each support early child vocabulary development – sensitivity and cognitive stimulation. We used observational data on expressed vocabulary, a measure that grows meaningfully over time, to test whether the absolute and relative effects of maternal sensitivity and stimulation on child vocabulary change with child age. We then tested whether mothers’ parenting behaviors themselves, measured on a rating scale or as mutually exclusive behaviors in separate categories, changed over time, possibly in response to children’s development.

Specific Effects of Sensitivity and Stimulation

Our results indicate that while both sensitivity and cognitive stimulation are critical to child vocabulary in the first three years, the relative effects of these dimensions shift throughout toddlerhood; sensitivity has a more substantial effect than stimulation in early development and this effect is relatively consistent over time, while cognitive stimulation gains importance over developmental time, as identified in previous research (Hubbs-Tait, Culp, Culp, & Miller, 2002). The sizeable effect of early sensitivity is consistent with literature on the importance of caregivers’ responsiveness to child cues in communicative interactions (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 1996; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2001; Tomasello & Farrar, 1986), rather than the amount of speech children hear. Further, our finding that the effect size of sensitivity on children’s vocabulary diminishes over developmental time, particularly between one and two years, provides evidence for the idea that the relative importance of sensitivity to vocabulary acquisition diminishes as children’s skills for vocabulary acquisition expand with their cognitive and linguistic skills, and become less dependent upon caregivers’ affective and social attunement (Hollich et al, 2000).

We found that the effect of mothers’ cognitive stimulation on children’s vocabulary increased throughout toddlerhood; by two years old, cognitive stimulation had become almost as important as sensitivity in its relation to child vocabulary, and by three years it had a greater relative effect. This is consistent with research showing that interventions aimed at helping parents to become “teachers” of their children can have positive effects on children’s vocabulary development, particularly for groups of families whose children are at greater risk (e.g., Ramey & Ramey, 1999; Wagner & Clayton, 1999).

Measured globally, we found no evidence that sensitivity and stimulation moderate each other, but rather they exert independent simultaneous influences on child development, which shift in importance over time. Though there is a moderate to strong correlation between these dimensions in the first three years of life, there is still sufficient variation to detect independent effects; thus, the lack of a significant interaction cannot be due simply to conflation in their measurement or conceptual inter-relatedness. However, future studies may yet find a dependent relationship between these dimensions using microanalytic techniques to more closely examine co-occurrence and sequences of behaviors within these dimensions.

Mothers’ Adaptations to Children’s Changing Needs

We found evidence through both the rating and coding systems that maternal behavior did indeed change. Using the rating system, we saw that mothers became more cognitively stimulating from infancy until mid-toddlerhood, but sensitivity did not change significantly, which is consistent with previous research (Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005; Holden & Miller, 1999; Landry et al., 2001). Given that it is sensitivity in infancy and cognitive stimulation in later toddlerhood that appear most important to children’s concurrent vocabulary development, our results indicate that mothers do, at least in part, shift their parenting behaviors in accordance with children’s developmental needs. This ability of mothers to adjust to their children’s needs is particularly important in this low-income sample because previous research has indicated that parents living in poverty or with less education are less likely to shift their behaviors as children grow (Lawrence & Shipley, 1996; Son & Morrison, 2010). This is all the more important because this sample of children, whose families are eligible for Early Head Start services, increasingly fell behind national norms for cognitive and language development over the first three years of life (Ayoub et al., 2009; Pan, Rowe, Singer, & Snow, 2005), but the Early Head Start Intervention, in part through its effects on parenting, helped to ameliorate the effects of family risks on children’s language (Ayoub, Vallotton, & Mastergeorge, 2011; Vallotton et al., 2012).

In addition to the increase in stimulation between one and two years old, we also identified a decrease in the ratings of mothers’ cognitive stimulation from two to three years. This may indicate that mothers were unable to keep up with the growing complexity of children’s developmental needs. An alternative explanation for the peak in cognitive stimulation around two years old is that it is in mid-toddlerhood when children are most demanding of their mothers’ attention and active engagement, and require mothers to recruit and redirect their attention to stay engaged in play interactions in meaningful ways. In contrast, in the third year of life, children develop more independence in regulating their own attention and play, thus mothers may respond with less cognitive stimulation given their children’s increase in self-regulated activities (e.g., Tamis-Lemonda, Bornstein, & Baumwell, 2001). It would be useful to further investigate the degree to which individual differences in these developmental shifts evoke related changes in parents’ behaviors, particularly if this were coupled with an examination of factors that make parents more or less sensitive to these cues.

Interestingly, our findings show that it is when children were three years that mothers’ cognitive stimulation had the biggest relative effect on their vocabulary, yet this is also when mothers’ stimulation had decreased. It may be that by three years old, children’s greater ability to determine and regulate their own play and lower demands for maternal engagement are interpreted by mothers to mean that children will not benefit from their intentional teaching behaviors. It may be that mothers’ sensitivity to changes in child behaviors leads them to withdraw more direct supports in order to make room for children’s independent play; this requires us to consider the concept of sensitivity at a higher level and over time as parents’ attention and response to children’s changing developmental needs. This collection of findings indicates specificity regarding timing of intervention (Landry, Smith, Swank, & Guttentag, 2008; Ramey & Ramey, 1999); mothers of older toddlers may benefit from interventions that provide information about when and how to provide meaningful stimulation that can continue to support their children’s language development.

Complementary Methodologies, Convergent Findings

Most studies take a single approach to measuring parenting, and assume stable, linear effects of parenting on children’s developmental outcomes. This study utilized two different approaches to measuring parenting in order to examine change in absolute frequencies of specific types of behaviors (coding system) as compared to overall perceived quality on the same dimensions (rating system). A recent study by Bornstein & Manian (2013) took a similar approach to examine whether there was a linear relationship between the mothers’ contingent responsiveness (i.e., percent of child behaviors responded to contingently) and sensitivity (rated emotional availability). Contingency and sensitivity were not linearly related; instead, a moderate level of contingency was seen as more sensitive than too little or too much. These findings and those of the current study indicate that we cannot conceptualize positive parenting behaviors and dimensions as linear in their relationship to parenting quality. Findings of the current study also reveal a changing relationship between parenting behaviors and children’s outcomes. Our study joins Bornstein and Manian (2013) in calling for nuanced examinations of dimensions of parenting qualities, and examination of points of convergence and divergence in different observational approaches to the measurement of parenting.

The relatively steady level of sensitivity over time, coupled with increasing cognitive stimulation – identified in both the rating and coding systems – draws into question the nature of sensitivity and how we, as a field, measure it. Perhaps sensitivity itself, if defined primarily as responsiveness, is indicated by an increase in cognitive stimulation in response to children’s developmental needs. This may mean shifts away from behaviors typically conceptualized as sensitive in order to provide a child with the stimulation he or she needs at the moment. That is, as the needs of children change over time, so do their demands on parents, and the true nature of sensitivity is that parents perceive and adjust to these changes to support optimal development. This view of sensitivity requires examination of contingent qualities of parenting over time. Though many studies and meta-analyses do identify sensitivity and cognitive stimulation as separate constructs (e.g., Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005; see review by Holden & Miller, 1999), it may be productive to re-consider the nature of sensitivity as a shift in stimulation in response to changes over time in child behaviors. However, this would require us to measure the construct on a different scale of time than is typical of the most studies that take a microanalytic approach. Another possible explanation for our findings on change in stimulation is that the cognitively stimulating behaviors – whether rated as a holistic construct or coded as discrete behaviors – reflect parents’ responses to their children’s immediate behaviors or interests in the moment; thus parents are seen as becoming more stimulating, when in fact it is toddlers who encourage their parents to act responsively and contingently in interactions. That is, as young children’s cognitive skills increase over time, parents are ‘signaled’ by their children in the moment to provide more frequent cognitive stimulation behaviors in recurring everyday contexts and activities (Bornstein et al, 2008; Feldman, 2003).

Understanding young children’s signals is critical to promote mutuality in the parent-child relationship. Given the importance of both stimulation and sensitivity for children at risk of delayed language, and that young children with greater communication skills receive both more stimulation (Girolametto & Weitzman, 2002) and sensitivity from their caregivers (Landry et al, 2008; Vallotton, 2009), current findings points to an important aspect of intervention - enhancing maternal responsiveness to infant cues and signals—in order to facilitate skills for infants at risk for delayed language. The timing of intervention is critical for facilitation of joint attention, which is supported by parents’ responsive interaction behaviors (Landry et al, 2008; Landry, Smith, & Swank, 2006).

Limitations and Future Directions

Though the use of two methods for assessing parenting behavior allowed us to address complementary questions at multiple levels, the observational methods used for both parenting and child language still pose limitations. First, both the dependent variable (child language) and independent variables (parent sensitivity and stimulation) came from the same observations, potentially inflating the strength of their relationships. However, the use of these observations to measure child vocabulary has been shown to be valid, as indicated by its relationship to a standardized measure (Pan et al., 2005). We chose not to use the standardized measure of child language available in the study sample because it was only completed at two times and could not be used to assess growth. However, future studies could use these measures to test whether there exist similar relationships between vocabulary at 1 and 2 years old, as measured by parental report, and parental sensitivity and stimulation at these same ages.

Second, the rating scales– specifically the definitions and examples of parenting qualities – may have set up a likely relationship between mothers’ stimulation and children’s vocabulary. The ratings of cognitive stimulation included the quality and quantity of the parents’ effortful teaching to enhance children’s cognitive and linguistic development by encouraging children to talk about materials, encouraging play in ways that teach concepts (e.g., colors, sizes), and using language to label child experiences or actions (e.g., ask questions about toys, present activities in sequences). Given the emphasis on parents’ teaching behaviors most readily observed in verbal acts, the strong relationship to child vocabulary is not surprising. Other measures of stimulation not emphasizing parents’ use of language might show weaker relationships to child language; alternatively, broader, more inclusive, measures of stimulation could reveal important relationships between parents’ non-verbal behaviors and child language. Another limitation of the rating scales is that they were not originally designed to be orthogonal; thus, as measured in this study, sensitivity and stimulation are less conceptually distinct than they could be, which may have reduced our ability to detect differences in their effects.

The sample in the current study was specifically a low-income sample, with varying levels of associated risks, but greater risks than a typical U.S. family. Further, the children in this sample were at greater risk of poor language and cognitive outcomes (Ayoub et al., 2009; Ayoub et al., 2011). Given that Baumwell and colleagues (1997) have shown that verbal sensitivity is more important for children with lower communication skills, the results of the current study, or at least the magnitude of the effects, may only be applicable to those with similar levels of risk. Another limitation is that, despite the high levels of risk prevalent in this sample, by and large, most mothers were at least moderately sensitive, truncating the possible variability. Thus, results of the current study may actually underestimate the importance of sensitivity.

It would be informative to examine the bidirectional and dynamic relationships between children’s growing cognitive, language, and social abilities and their parents’ sensitive and stimulating behaviors. It is always hard to disentangle the dynamic influences that take place within dyads, but incorporating additional caregivers (e.g., fathers, educators) and using more advanced analytic techniques (e.g., dyadic data analysis) could prove productive approaches.

Conclusion