Abstract

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is an often fatal disease with limited treatment options. Whereas current data support the notion that, in pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAECs), expression of transcription factor hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is increased, the role of HIF-1α in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) remains controversial. This study investigates the hypothesis that, in PASMCs from patients with PAH, decreases in HIF-1α expression and activity underlie augmented pulmonary vascular contractility. PASMCs and tissues were isolated from nonhypertensive control patients and patients with PAH. Compared with controls, HIF-1α and Kv1.5 protein expression were decreased in PAH smooth muscle cells (primary culture). Myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation and MLC kinase (MLCK) activity—major determinants of vascular tone—were increased in patients with PAH. Cofactors involved in prolyl hydroxylase domain activity were increased in PAH smooth muscle cells. Functionally, PASMC contractility was inversely correlated with HIF-1α activity. In PASMCs derived from patients with PAH, HIF-1α expression is decreased, and MLCK activity, MLC phosphorylation, and cell contraction are increased. We conclude that compromised PASMC HIF-1α expression may contribute to the increased tone that characterizes pulmonary hypertension.—Barnes, E. A., Chen, C.-H., Sedan, O., Cornfield, D. N. Loss of smooth muscle cell hypoxia inducible factor-1α underlies increased vascular contractility in pulmonary hypertension

Keywords: MLCK, pMLC, prolyl hydroxylase domain, PAH, vasoconstriction

Despite significant new knowledge surrounding the pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and focused therapies that are specifically designed to treat PAH, morbidity and mortality remains high. Over the past decade, even with the introduction of novel, expensive, and intensive treatments, survival of patients with PAH has increased only modestly, with a median survival of 7 yr (1). In the context of pulmonary hypertension (PH), pulmonary vasoconstriction is followed by remodeling of the vascular wall, which entails increased medial thickening, cell hypertrophy, proliferation, and migration (2). Over the long term, PH leads to right ventricular hypertrophy, right heart failure, and death. Whereas pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) play a central role in the pathobiology of PH, molecular and physiologic changes that unfold in PASMCs in the context of PH remain incompletely understood.

Hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), a transcription factor that facilitates cellular adaptation to low O2 tension states (3), likely plays a central role in the development of PH. In a murine model, haploinsufficiency of HIF-1α attenuates hypoxia-induced increases in pulmonary artery (PA) pressure, right ventricular hypertrophy, and pulmonary vascular remodeling—observations that support a role for HIF-1α in modulating pulmonary vascular remodeling (4).

Further insight has been gained in murine models with smooth muscle cell (SMC)–specific deletions of HIF-1α. In mice with a constitutive deletion of SMC HIF-1α (SM22α-HIF-1α−/−), PA pressure is higher compared with controls under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions in the absence of enhanced vascular remodeling (5), which argues for a role for PASMC HIF-1α in maintaining the normally low resistance of pulmonary circulation. In mice with a tamoxifen-inducible, smooth muscle–specific deletion of HIF-1α (HIF-1α-SMM-Cre), PA pressure and vascular remodeling are attenuated under conditions of chronic hypoxia (6). Thus, whereas data from murine models support the concept that HIF-1α expression in PASMCs plays a role in the development of PH, whether it increases or decreases pulmonary vascular tone and/or remodeling remains controversial.

Prior studies from human PA tissue from patients with PAH demonstrated increased HIF-1α expression (7–9); however, cell-specific HIF-1α expression and activity remain uncertain. To address this issue more definitively, we procured explanted human tissue, PASMCs, and PA endothelial cells (PAECs) from patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) who underwent lung transplantation as well as tissue, PASMCs, and PAECs from nonhypertensive donor lungs (control patients).

In the present report, we tested the hypothesis that in PASMCs from patients with severe PAH, the expression of HIF-1α is decreased and correlates inversely with myosin light chain phosphorylation (pMLC), an important determinant of vascular tone. From a functional perspective, we postulated that contractility would be greater in SMCs from patients with PAH compared with control cells. Furthermore, we addressed the notion that in PASMCs from patients with PAH, increased prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) protein activity underlies the decrease in HIF-1α expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

IPAH and control samples

PASMCs isolated from control patients (n = 6) and patients with IPAH (n = 6), PAECs isolated from control patients (n = 4) and patients with IPAH (n = 4), and corresponding formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded lung tissue sections were provided by the Pulmonary Hypertensive Breakthrough Initiative. Additional lung tissue samples isolated from control patients (n = 1) and patients with IPAH (n = 1) were provided by the National Disease Research Interchange (Philadelphia, PA, USA). Isolated PASMCs were cultured in SmBM (Lonza, Mapleton, IL, USA) that contained 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) with 0.1% insulin, 0.2% human fibroblastic growth factor-B (hFGF-B), 0.1% human epidermal growth factor, and 0.1% gentamicin/amphotericin (GA-1000). Isolated PAECs were cultured in EBM-2 (Lonza) that contained 5% FBS with 0.04% hydrocortisone, 0.4% hFGF-B, 0.1% VEGF, 0.1% R3-IGF-1, 0.1% ascorbic acid, 0.1% human epidermal growth factor, and 0.1% gentamicin/amphotericin (GA-1000). Isolated PASMCs and PAECs between passages 2–6 were used throughout this study. All cell lines were examined for expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), smooth muscle myosin heavy chain 11 (MHC11), SM22α, and calponin (markers of vascular SMCs) as well as CD31 and VE-cadherin (markers of vascular ECs).

Western immunoblotting

Isolated PASMCs and PAECs were lysed with 0.5% NP-40 buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 2.5 mM EDTA; 0.5% NP-40; 1 mM Na3VO4; 1 mM PMSF; 10 μg/ml aprotinin; 10 μg/ml leupeptin; and 5 μM HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA)]. Protein content was quantified by using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Ten to 20 μg of protein/sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. Immobilon-P (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) membranes were incubated with primary Abs to detect HIF-1α (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), HIF-2α (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), MLC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), pMLC (Abcam), PHD1 (Novus, Littleton, CO, USA), PHD2 (Novus), PHD3 (Novus), MLC kinase (MLCK; Abcam), Kv1.5 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary Abs, followed by detection with ECL reagents (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Results shown represent the quantification of HIF-1α, HIF-2α, Kv1.5, and pMLC expression by densitometry relative to β-actin or MLC expression, respectively (n = 6 for control; n = 6 for IPAH for PASMCs; n = 4 for control; n = 4 for IPAH for PAECs).

PASMCs and PAECs isolated from control patients (n = 4) and patients with IPAH (n = 4) as well as human embryonic kidney 293 cells were lysed with 0.5% NP-40 buffer. Lung tissues isolated from control patients (n = 1) and patients with IPAH (n = 1) were homogenized with RIPA buffer [150 mM NaCl; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 1% Triton X-100; 0.1% SDS; 0.25% sodium deoxycholic acid; 2.5 mM EDTA; 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF; 10 μg/ml aprotinin; 10 μg/ml leupeptin; and 5 μM HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (Calbiochem)]. Four random sections per lung sample were homogenized separately for analysis. Protein content was quantified by using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Twenty micrograms whole-cell lysate/sample and 30 μg lung tissue homogenate/sample were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. Immobilon-P membranes were incubated with primary Abs to detect HIF-3α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary Abs, followed by detection with ECL reagents (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Results shown represent the quantification of HIF-3α expression by densitometry relative to β-actin expression.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from control and IPAH PASMCs by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and reverse transcribed by using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) per the manufacturer's instructions. Fifty nanograms of cDNA was used per PCR, with each sample analyzed in triplicate (n = 6 for control and n = 6 for IPAH). PCR was performed using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays Products (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PCR conditions were as follows: 3 min at 95°C for 1 cycle, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 s and 55°C for 30 s. Results were analyzed by using the comparative Ct method. Results shown represent the quantification of HIF-1α mRNA (HIF1A) and Kv1.5 mRNA (KCNA5) relative to 18S rRNA expression.

Immunocytochemistry

To visualize nuclear HIF-1α expression, control and IPAH PASMCs were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, blocked and permeabilized in VSVG blocking solution (0.1% Triton X-100, 15 mg/ml glycine, 2.5% FBS in PBS) for 1 h, then incubated with HIF-1α (1:400; GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA) Ab for 1 h in VSVG blocking solution, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 568 α-rabbit Ab (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h, then mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium with DAPI (magnification ×200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Results shown represent the percentage of nuclear HIF-1α–expressing cells—the number of nuclear HIF-1α–positive cells over the total number of HIF-1α–expressing cells—with a minimum of 100 cells counted per sample (n = 3 for control and n = 3 for IPAH).

To visualize pMLC, cells seeded on collagen-coated coverslips were fixed and permeabilized as described above, incubated with vinculin (1:400; Millipore) and pMLC (1:50; Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA) Abs for 1 h, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 568 α-rabbit and Alexa Fluor 488 α-mouse antibodies (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h, and then mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium with DAPI (magnification ×200).

To assess focal adhesions, cells seeded on collagen-coated coverslips were fixed and permeabilized as described above, incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (1:40; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and vinculin (1:200) Abs for 1 h, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 568 α-mouse antibody (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min, then mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium with DAPI (magnification ×200). Results shown represent the quantification of the number of focal adhesions formed per cell at each time point (1 and 18 h postseeding) as observed by vinculin staining with a minimum of 100 cells counted per sample (n = 3 for control and n = 3 for IPAH).

To assess for cell lineage, cells isolated from control patients and patients with IPAH were examined for α-SMA expression (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich), MHC11 (1:100; Abcam), SM22α (1:800; Abcam), and calponin (1:50; Abcam). In brief, cells were fixed and permeabilized as described above, then incubated with each specific Ab for 1 h, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 568 α-rabbit or Alexa Fluor 488 α-mouse Abs for 1 h, then mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium with DAPI (magnification ×200). Results shown represent the percentage of α-SMA, MHC11, SM22α, and calponin-expressing PASMCs—the number of antigen-positive cells over the total number of cells—with a minimum of 100 cells counted per sample (n = 3 for control and n = 3 for IPAH).

Immunohistochemistry

To visualize HIF-1α, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded lung sections from control patients and patients with IPAH were deparaffinized and rehydrated, incubated with Vector Antigen Unmasking Solution (Vector Laboratories) for 45 min at 95°C, incubated with 3% H2O2 for 5 min to quench endogenous peroxidase activity, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100/PBS solution for 20 min, and blocked with normal blocking serum (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min, followed by incubation with HIF-1α Ab (1:50; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. Sections were then incubated with reagents from the Vectastain Elite ABC Kit and ImmPact DAB Peroxidase Substrate (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sections were counterstained with Harris Hematoxylin (BBC Biochemical, Mt. Vernon, WA, USA), dehydrated, cleared, and then mounted with Permount (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

To visualize pMLC, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded lung sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, incubated with Universal Antigen Retrieval Reagent (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 30 min at 95°C, permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100/PBS solution for 30 min, incubated with 100 mM glycine solution (pH 7.5) for 20 min to quench autofluorescence, blocked with Sea Block Blocking Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 40 min, and blocked with Fc Receptor Blocker (Innovex Biosciences, Richmond, CA, USA) for 30 min, followed by incubation with pMLC Ab (1:50; Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. Sections were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 568 α-rabbit antibody (1:200) for 1 h, followed by incubation with 1 μg/ml Hoechst solution (Sigma-Aldrich) to visualize nuclei, then mounted with 70% glycerol solution.

To visualize HIF-3α, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded lung sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, incubated with Universal Antigen Retrieval Reagent for 30 min at 95°C, permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100/PBS solution for 30 min, incubated with 100 mM glycine solution (pH 7.5) for 20 min to quench autofluorescence, blocked with Sea Block Blocking Buffer for 40 min, and blocked with Fc Receptor Blocker for 30 min, followed by incubation with HIF-3α (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and α-SMA (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich) or vimentin (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) Abs overnight at 4°C. Sections were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 568 α-rabbit and Alexa Fluor 488 α-mouse or Alexa Fluor 488 α-goat antibodies (1:200) for 1 h, followed by incubation with 1 μg/ml Hoechst solution to visualize nuclei, then mounted with 70% glycerol solution. Results shown represent the quantification of pulmonary cells that coexpress HIF-3α and vimentin with a minimum of 15 fields examined per sample per high-powered field.

ATP and O2 assay

CellTiter-Glo luminescent assay (Promega, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used to measure intracellular ATP and O2 levels in control and IPAH PASMCs according to the manufacturer's protocol. In brief, 1 × 104 cells were seeded in triplicate (n = 4 for control and n = 4 for IPAH) in a 96-well plate. After 1 h, an equal volume of CellTiter-Glo reagent was added with luminescence recorded on a GloMax luminometer (Promega). Luminescent signal is proportional to the amount of intracellular ATP and O2 present. As a control for intracellular O2 content, cells were exposed to hypoxia (1% O2, 1 h) or hyperoxia (75% O2, 1 h). Results shown represent the relative light units ×103 per sample.

Fe assay

Iron assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to measure intracellular iron(II) (Fe2+) and iron(III) (Fe3+) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate (n = 3 for control and n = 3 for IPAH). Results shown represent the concentration of Fe2+ and Fe3+ in 40 μg of sample.

Ascorbate assay

Ascorbic acid assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to measure intracellular ascorbate (Asc) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate (n = 6 for control and n = 6 for IPAH). Results shown represent the concentration of ascorbic acid in 40 μg of sample.

MLCK activity assay

To directly assess MLCK activity in PASMCs from control patients and patients with IPAH, an MLCK activity assay (Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA) was performed with each sample analyzed in duplicate (n = 4 for control and n = 4 for IPAH). Results shown represent the amount (ng) of active MLCK in 40 μg of sample.

For MLCK assays with small interfering RNA (siRNA)–transfected human PASMCs (hPASMC; Lonza), cells were lysed 72 h after transfection and analyzed for MLCK activity in triplicate. Results shown represent the amount (ng) of active MLCK in 5 μg of sample.

To measure MLCK activity in hPASMCs transfected with scrambled HIF-1α (siHIF-1α), cell lysates were incubated ± λ protein phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) during the kinase reaction, with each sample analyzed in triplicate. Results shown represent the amount (ng) of active MLCK in 5 μg of sample.

Rho kinase activity assay

To directly assess Rho kinase activity in PASMCs from control patients and patients with IPAH, a Rho kinase activity assay (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol, with each sample analyzed in duplicate (n = 4 for control and n = 4 for IPAH). Results shown represent the amount (ng) of active Rho kinase in 40 μg of sample.

MLCK inhibitor assay

To analyze pMLC expression, PASMCs from control patients and patients with IPAH at 50% confluence were treated with ML-7 hydrochloride [1-(5-iodonaphthalene-1-sulfonyl)-[1H]-hexahydro-1,4-diazepine hydrochloride; Santa Cruz Biotechnology], an MLCK-specific inhibitor, at 0, 1.25, 2.5, or 5.0 μM for 1 h. Samples were analyzed by Western immunoblot. Results are expressed as the ratio of pMLC to unphosphorylated MLC as measured by densitometry (n = 3 for control and n = 3 for IPAH).

Calcium imaging

To assess dynamic changes in [Ca2+]i in siRNA-transfected hPASMCs, calcium imaging was performed using the calcium-sensitive fluorophore, fura-2 AM (fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Subconfluent monolayer of PASMCs was loaded with 0.5 μM fura-2 AM for 20 min (5% CO2, 37°C) at 48 h post-transfection. After a stable baseline was measured (21% O2, 30 min), oxygen tension was decreased (approximately 20–25 Torr, 30 min) and [Ca2+]i was measured. Ratiometric imaging was performed with the excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 510 nm. For each experiment, approximately 5 cells per coverslip were visualized with ratiometric data that were acquired from individual cells (n = 21 cells, 4 coverslips). Apparent [Ca2+]i is presented as the ratio of fluorescence signals obtained (340/380 nm).

Collagen gel contraction assay

Collagen gel contraction assays were performed as reported previously (10). In brief, 150 μl of collagen (PureCol EZ Gel Bovine Collagen Solution Type I in DMEM-F12, 5mg/ml; Advanced BioMatrix, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was portioned in aliquots per well of a 48-well plate. After 1 h of polymerization, 4 × 104 cells were added per well in 300 μl of SmBM plus supplements. PASMCs from control patients and patients with IPAH were seeded in triplicate (n = 6 for control and n = 6 for IPAH). After 1 h of incubation, the sides of the collagen wells were gently detached from the walls of the wells by using sterile 200 μl pipette tips to initiate cell-mediated collagen contraction. After 18 h, collagen gels were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min. The degree of contraction was assessed by measuring the area of the gels with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). In brief, the cross-sectional diameter of each gel was measured (2 diameter measurements per gel sample). The following formula was used to determine the elliptical area: A = π(a/2)(b/2), where a and b represent separate diameter measurements. Results shown represent the collagen gel surface area as a percentage relative to the area of no cell control (no SMC).

For collagen gel assays, hPASMCs transfected with siRNA were trypsinized and counted 30 h after transfection. In brief, 4 × 104 of siRNA-transfected hPASMCs were added per well to polymerized collagen gels. Remaining cells were lysed and analyzed for HIF-1α and pMLC expression. After 18 h, collagen gels were fixed. Results shown represent the collagen gel surface area as a percentage of control [scrambled nontargeted control (siNTC)-transfected cells].

For collagen gel assays with plasmid-transfected hPASMCs, 26 h post-transfection, cells were trypsinized and counted. Transfected hPASMCs (4 × 104) were added to polymerized collagen gels as described. Remaining cells were lysed and analyzed for HIF-1α and pMLC. After 18 h, collagen gels were fixed. Results shown represent the collagen gel surface area as a percentage of control (vector-transfected cells).

siRNA transfection

hPASMCs at 60% confluence were transfected by using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer protocol. In brief, siRNA specific for human HIF-1α, siHIF-1α (On-TargetPlus SmartPool; Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA), or scrambled nontargeted control siRNA, siNTC (On-TargetPlus ControlPool; Dharmacon), at a final concentration of 50 nM, was transfected per 60-mm plate. At 20 h post-transfection, cells were refed with fresh medium.

Constitutively active HIF-1α transfection

The HIF-1α expression plasmid, a constitutively active form of HIF-1α that contains the double mutation P402A/P564A, was a kind gift from Dr. A. J. Giaccia (Stanford University). Empty vector, pcDNA3, served as transfection control. hPASMCs were transfected by using the lipofectamine LTX/Plus method (Thermo Fisher Scientific) per manufacturer instructions. In brief, cells at 90% confluence were transfected with 5 μg of DNA per 60-mm plate. At 20 h post-transfection, cells were refed with fresh medium.

Drug treatment

Collagen gel contraction assays were performed as previously described. IPAH PASMCs (4 × 104) were added to polymerized collagen gels in the presence of 1 mM DMOG (dimethyloxalylglycine; Calbiochem), 5 mM Asc (Sigma-Aldrich), or vehicle control. After 18 h, collagen gels were fixed. Results shown represent the collagen gel surface area as a percentage relative to the area of no cell control (no SMC). To analyze HIF-1α and pMLC expression, IPAH cells at 50% confluence were treated with 1 mM DMOG or 5 mM Asc for 4 h. Results shown represent the quantification of HIF-1α and pMLC expression by densitometry relative to β-actin or MLC expression, respectively (n = 3 for IPAH).

To analyze HIF-1α expression, control and IPAH PASMCs at 50% confluence were treated with 5 μM DMOG or DMSO for 4 h. Results shown represent the quantification of HIF-1α expression by densitometry relative to β-actin expression (n = 3 for control and n = 3 for IPAH).

To analyze Kv1.5 expression, hPASMCs at 50% confluence were treated with 5 mM Asc every 24 h for a period of 3 d. Results shown represent the quantification of Kv1.5 and HIF-1α expression by densitometry relative to β-actin expression.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± sem. Statistical significance was assessed with Student’s t test. A value of P ≤ 0.05 was taken as the threshold level for statistical significance. All experiments were repeated a minimum of 3 times.

RESULTS

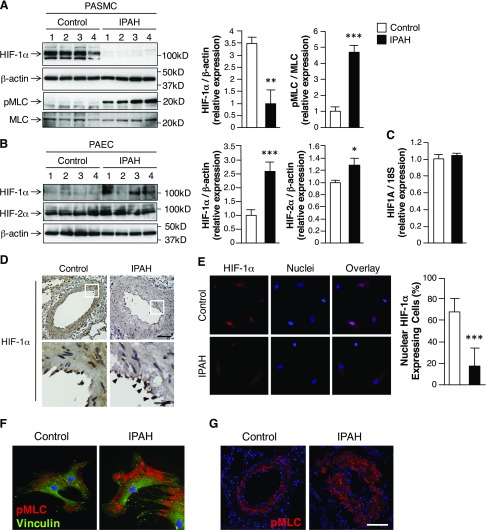

HIF-1α protein expression is decreased and pMLC is increased in PASMCs from patients with PAH

To determine whether HIF-1α is decreased in PASMCs from patients with PAH, we measured HIF-1α protein expression in PASMCs that were isolated from control patients and patients with PAH (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). To confirm that isolated cells were of SMC lineage, all cell lines were examined for expression of α-SMA, MHC11, SM22α, and calponin, which are markers of vascular SMC (Supplemental Fig. 1). Overall, HIF-1α protein expression was decreased and pMLC was increased in PASMCs from patients with PAH compared with control cells (Fig. 1A). In contrast, HIF-1α expression was increased in PAECs from patients with PAH compared with control cells (Fig. 1B). HIF-1α mRNA expression did not differ in PASMCs from controls compared with patients with PAH (Fig. 1C), which supported the notion that HIF-1α is differentially post-translationally regulated in the SMC from PAH compared with control patients. Consistent with recent reports that identified PAEC HIF-2α as a critical mediator of severe PAH in murine models, we found that HIF-2α expression increased in PAECs from patients with PAH (Fig. 1B) (11, 12). HIF-2α was minimally expressed in PASMCs and did not differ between controls and patients with PAH (data not shown).

Figure 1.

SMC loss of HIF-1α in PA of patients with PAH. A) Western immunoblots of HIF-1α and pMLC expression in PASMCs that were isolated from control patients and patients with IPAH. β-Actin expression serves as loading control. MLC expression represents unphosphorylated MLC. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 6 per group). B) Western immunoblots of HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression in PAECs that were isolated from control patients and patients with IPAH. β-Actin expression serves as loading control. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 4 per group). C) Real-time quantitative PCR to detect HIF-1α mRNA (HIF1A) in control and IPAH isolated PASMCs. 18S rRNA expression serves as internal control. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 6 per group). D) Representative images of HIF-1α expression in PA from control patients and patients with IPAH. Arrowheads denote HIF-1α expression in IPAH PAECs within the intimal layer (HIF-1α, brown; hematoxylin, purple). Magnification, ×200. Scale bar, 100 μm. Enlarged images: magnification, ×1000. Scale bar, 25 μm. E) Representative images of HIF-1α–expressing cells from control and IPAH isolated PASMCs (HIF-1α, red; nuclei, blue; overlay, magenta). Bars represent means ± sem (n = 3 per group). F) Representative images of pMLC expression in control and IPAH isolated PASMCs (pMLC, red; vinculin, green; nuclei, blue). G) Representative images of pMLC expression in PA from control patients and patients with IPAH (pMLC, red; nuclei, blue). Magnification, ×200. Scale bar, 50 μm. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

HIF-1α expression and localization was analyzed by immunohistochemistry. There was strong nuclear staining for HIF-1α in both SMCs and ECs in the PA of control samples (Fig. 1D). In contrast, HIF-1α expression was relatively diminished within the SMCs of the PA from patients with PAH. In several PAH patient samples, EC HIF-1α expression was preserved even in the absence of SMC HIF-1α expression (arrowheads). Consistent with prior reports, HIF-1α was localized in the nucleus in isolated control PASMCs under normoxic conditions (Fig. 1E) (13–15). Of cells that expressed HIF-1α, ∼70% of control PASMCs expressed nuclear HIF-1α. In contrast, ∼20% of PAH SMCs expressed nuclear HIF-1α (Fig. 1E, graph). Altogether, these results are consistent with prior reports that demonstrated nuclear HIF-1α expression in the intimal layer of remodeled PA and in ECs within plexiform lesions of patients with PAH (7–9).

Compared with control cells, PASMCs from patients with PAH expressed more pMLC at the cell periphery, which suggested that SMCs from patients with PAH maintain a more contractile phenotype (Fig. 1F). These findings correlate with pMLC expression and localization as analyzed by immunohistochemistry. There was strong cytosolic staining for pMLC in the SMCs in the remodeled PA of patients with PAH (Fig. 1G).

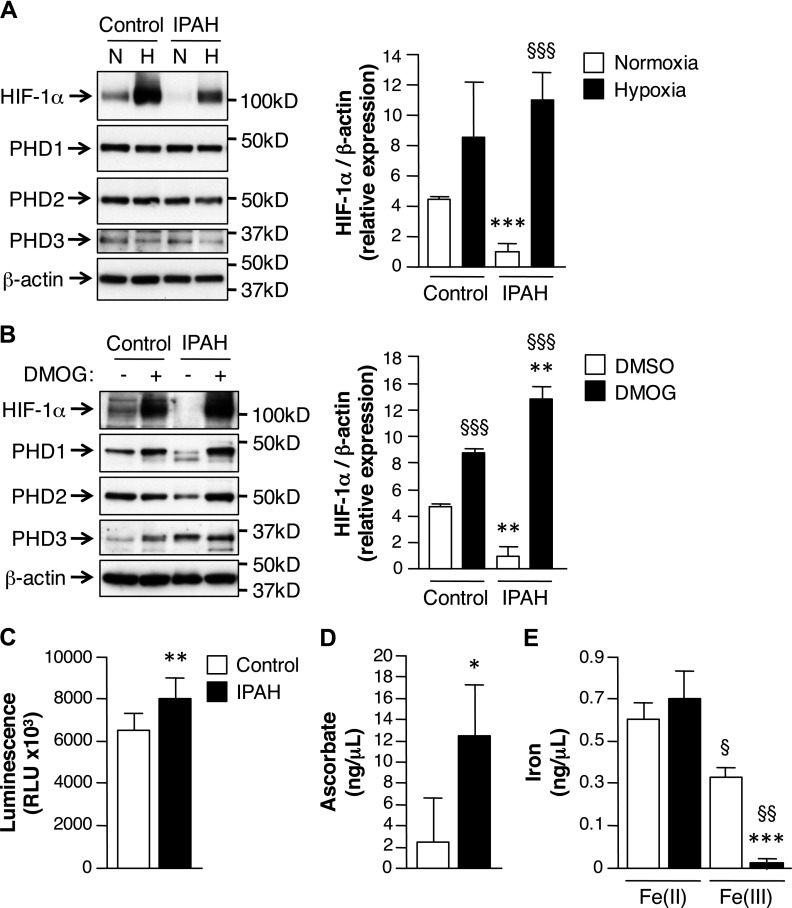

Prolyl hydroxylase activity is increased in PASMCs from patients with PAH

Under normoxic conditions, prolyl hydroxylase domain protein (PHD) family members hydroxylate HIF-1α, targeting it for degradation (16, 17). In normoxia, HIF-1α protein was present in PASMCs from controls, but was minimally expressed in cells from patients with PAH (Fig. 1A). Hypoxic exposure (1% O2, 1 h) increased HIF-1α protein expression in PASMCs from patients with PAH (Fig. 2A), which suggested that under normoxic conditions, PHD activity may be significantly greater in PASMCs from patients with PAH. To assess the contribution of PHD activity to HIF-1α stability, cells were treated with the PHD inhibitor, DMOG, which increased HIF-1α protein expression significantly more in DMOG-treated PAH compared with untreated PAH PASMCs (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

PHD activity is increased in PASMCs from patients with PAH. A) PASMCs that were isolated from patients with IPAH were subjected to normoxic (N; 21% O2) or hypoxic (H; 1% O2) conditions for 1 h and were analyzed for protein expression by Western immunoblot. β-Actin expression serves as loading control. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 3 per group). ***P ≤ 0.001, IPAH vs. control; §§§P ≤ 0.001, hypoxia vs. normoxia. B) PASMCs from control patients and patients with IPAH were treated with or without 5 μM DMOG for 4 h. β-Actin expression serves as loading control. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 3 per group). **P ≤ 0.01, IPAH vs. control; §§§P ≤ 0.001, DMOG vs. DMSO. C) CellTiter-Glo luminescent assay was performed to measure intracellular O2 levels. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 4 per group). **P ≤ 0.01. D, E) Ascorbic acid (D) and iron assays (E) were used to measure intracellular Asc (n = 6 per group) and iron(II and III; n = 3 per group). Bars represent means ± sem. *P ≤ 0.05, ***P ≤ 0.001, IPAH vs. control; §P ≤ 0.05, §§P ≤ 0.01, Fe3+ vs. Fe2+ for each group.

To provide further mechanistic insight, the contribution of intracellular cofactors that modulate PHD activity were evaluated (17, 18). Intracellular O2 levels were measured in PASMCs from control patients and patients with PAH. Under normoxic conditions, O2 levels were significantly higher in PAH compared with control cells (Fig. 2C). Intracellular levels of PHD cofactors, Asc and iron, were also determined. Intracellular Asc levels were significantly higher in PAH compared with control PASMCs (Fig. 2D), which would reduce Fe3+ back to Fe2+ to maintain the PHD complex in an active state. Consistent with increased Asc in PASMCs from PAH, there was significantly less Fe3+ present in PAH compared with control PASMCs (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these results support the proposition that under normoxic conditions, PHD activity is enhanced in PAH SMCs, owing, in part, to increased intracellular O2 and Asc levels. The result of augmented PHD activity is decreased HIF-1α protein expression.

MLCK activity is increased in PASMCs from patients with PAH

Because we found a significant increase in expression of pMLC in PASMCs that were isolated from patients with PAH compared with controls (Fig. 1A), MLCK and Rho kinase activities were measured in both cell types. MLCK activity was higher in PASMCs from patients with PAH compared with controls (Fig. 3A), whereas Rho kinase activity did not differ (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that increased pMLC in PASMCs from patients with PAH is derived from an increase in MLCK activity. To further address this possibility, PASMCs were treated with the MLCK specific inhibitor, ML7 (ML-7 hydrochloride). In control PASMCs, inhibition of MLCK activity had no effect on pMLC, whereas in PASMCs from patients with PAH, ML7 caused a dose-dependent decrease in pMLC (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

PASMCs from patients with PAH have enhanced MLCK activity. A, B) MLCK (A) and Rho kinase (B) activity assays were performed to assess the activities of each respective kinase in PASMCs that were isolated from control patients and patients with IPAH. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 4 per group). *P ≤ 0.05. C) Western immunoblots of MLCK, HIF-1α, and pMLC expression in control and IPAH PASMCs treated with 0, 1.25, 2.5, or 5.0 μM ML7 (ML-7 hydrochloride) for 1 h. β-Actin expression serves as loading control. MLC expression represents unphosphorylated MLC. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 3 per group). *P ≤ 0.05, ***P ≤ 0.001, IPAH vs. respective control; §P ≤ 0.05, §§P ≤ 0.01, treated IPAH vs. untreated IPAH. D) MLCK activity was examined in PASMCs transfected with siRNA for siNTC or siHIF-1α. HIF-1α and MLCK expression was examined by Western immunoblot. β-Actin expression serves as loading control. Bars represent means ± sem. **P ≤ 0.01. E) MLCK activity was examined in PASMCs transfected with siHIF-1α incubated with λ protein phosphatase (lambda PP). Bars represent means ± sem. **P ≤ 0.01, lambda PP-treated vs. untreated.

To further address the relationship between MLCK activity and HIF-1α expression, MLCK activity was determined in siRNA-transfected hPASMCs. As shown in Fig. 3D, HIF-1α depletion increased MLCK activity by ∼5-fold compared with siNTC-transfected cells.

To further elucidate the mechanism by which the loss of HIF-1α expression promotes MLCK activity, MLCK activity was determined in siHIF-1α–transfected hPASMCs in the presence of λ protein phosphatase. Phosphorylation of MLCK reduces its kinase activity toward MLC (19). As shown in Fig. 3E, dephosphorylation of MLCK with λ protein phosphatase increased MLCK activity by ∼50%, which suggested that HIF-1α may modulate PASMC contractility by directly affecting MLCK phosphorylation.

Loss of HIF-1α potentiates hypoxia-induced increase in PASMC [Ca2+]i

Fluorescent microscopy was used to examine cytosolic calcium concentrations [Ca2+]i. Acute hypoxia increased hPASMC [Ca2+]i in both siNTC- and siHIF-1α–transfected cells (Fig. 4A); however, the hypoxia-induced increase was greater in PASMCs in which HIF-1α was depleted compared with siNTC-transfected cells.

Figure 4.

Kv1.5 expression is decreased in PASMCs from patients with PAH. A) Calcium imaging analysis was performed to assess [Ca2+]i levels in PASMCs transfected with siNTC or siHIF-1α. Fluorescence ratios (F340/F380) indicate apparent [Ca2+]i. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 21 cells examined per group). *P ≤ 0.05, hypoxia siHIF-1α vs. hypoxia siNTC. B) Western immunoblot of Kv1.5 expression in PASMCs that were isolated from control patients and patients with IPAH. β-Actin expression serves as loading control. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 4 per group). C) Real-time quantitative PCR to detect Kv1.5 (KCNA5) mRNA in PASMCs transfected with a plasmid encoding for vector alone (vector) or a constitutively active form of HIF-1α (HIF-1αCA). 18S rRNA expression serves as internal control. Bars represent means ± sem. D) Western immunoblots of HIF-1α and Kv1.5 expression in PASMCs transfected with vector or HIF-1αCA. β-Actin expression serves as loading control. E) Western immunoblots of HIF-1α and Kv1.5 expression in PASMCs treated with or without 5 mM Asc daily for 3 d. β-Actin expression serves as loading control. Bars represent means ± sem. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, Asc treated vs. respective untreated.

Kv1.5 expression is decreased in PASMCs from patients with PAH

The dysfunction of voltage-gated potassium (KV) channels—in particular the Kv1.5 channel—is an underlying feature of PAH (20–23). Consistent with previous reports, protein expression of Kv1.5 is significantly decreased in PAH compared with control PASMCs (Fig. 4B) (20, 23).

To further address the relationship between HIF-1α and Kv1.5 expression, hPASMCs were transfected with a constitutively active form of HIF-1α. Overexpression of HIF-1α increased Kv1.5 mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 4C, D). hPASMCs treated with Asc, a PHD cofactor (17, 18), decreased HIF-1α and Kv1.5 expression (Fig. 4E).

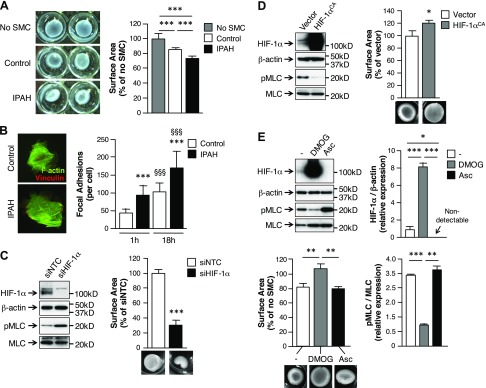

Contractility is increased in PASMCs from patients with PAH

To determine whether PASMCs from control patients and patients with PAH differ relative to contractility, collagen gel contraction assays were performed. PASMCs that were isolated from patients with PAH caused a ∼25% reduction in collagen gel surface area compared with control gels (Fig. 5A). Isolated PASMCs from control patients exhibited ∼15% reduction in collagen gel surface area. As a metric of force generation, we measured focal adhesion density. Within 1 h, PASMCs from patients with PAH demonstrated ∼2-fold higher number of focal adhesions than did control cells (Fig. 5B). After 18 h of incubation, PASMCs from patients with PAH still demonstrated a significantly higher number of focal adhesions (∼1.7-fold) compared with control cells.

Figure 5.

PASMCs from patients with PAH have enhanced contractility. A) Collagen gel contraction assays were performed to assess PASMC contraction. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 6 per group). B) Representative images of focal adhesions in control and IPAH-isolated PASMCs (vinculin, red; F-actin, green). Bars represent means ± sem of the number of focal adhesions formed per cell, as observed by vinculin staining (n = 3 per group). ***P ≤ 0.001, IPAH vs. control; §§§P ≤ 0.001, 18 h vs. 1 h for each group. C, D) Collagen gel contraction assays were performed to assess the contribution of HIF-1α expression on PASMC contraction. HIF-1α and pMLC expression was examined in PASMCs transfected with siNTC or siHIF-1α (C), or transfected with a plasmid encoding for vector alone (vector) or a constitutively active form of HIF-1α (HIF-1αCA) (D) by Western immunoblot. Bars represent means ± sem. *P ≤ 0.05, ***P ≤ 0.001, HIF-1α transfected vs. respective control. E) Collagen gel contraction assays were performed to assess the contribution of HIF-1α expression (±1 mM DMOG or 5 mM Asc) toward IPAH SMC contraction. HIF-1α and pMLC expression was examined by Western immunoblot. Bars represent means ± sem (n = 3). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

Relationship between HIF-1α expression and PASMC contractility

We previously demonstrated that loss of HIF-1α in either murine or hPASMCs increased pMLC under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions (5). To further address the physiological role that the loss of HIF-1α plays in SMC contraction, siHIF-1α–transfected hPASMCs were subjected to collagen gel contraction assays. As shown in Fig. 5C, depletion of HIF-1α increased pMLC and SMC contraction by ∼70% compared with collagen gels incubated with siNTC-transfected cells. In contrast, overexpression of constitutively active HIF-1α in hPASMCs decreased pMLC and blocked SMC contraction completely (Fig. 5D).

To further detail the relationship between HIF-1α, pMLC, and SMC contraction in the context of PAH, PASMCs from patients with PAH were also examined. As shown in Fig. 5E, untreated PASMCs from patients with PAH expressed relatively minimal amounts of HIF-1α protein and contracted by ∼20% compared with control gels (no SMC). In contrast, stabilization of HIF-1α protein by PHD inhibitor, DMOG, increased HIF-1α protein expression, decreased pMLC expression, and completely blocked SMC contraction. Cells were also treated with Asc, a cofactor for constitutive PHD activity (17, 18). Asc treatment decreased HIF-1α expression in PASMCs from patients with PAH, which provided evidence that by increasing PHD activity, HIF-1α protein expression can be decreased, with PASMC contractility and pMLC expression increased. Taken together, these results provide further evidence that supports a role for SMC HIF-1α activity in regulating pMLC expression and vascular tone.

DISCUSSION

The present data provide support for the evolving theory that HIF-1α plays a regulatory role in both hypoxic and normoxic conditions. Specifically, in the pulmonary circulation, HIF-1α plays a central role in determining the contractile state of PASMCs under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. In PASMCs that are derived from patients with PAH, expression and activity of HIF-1α are decreased, primarily as a result of an increase in PHD activity. The notion of a cell-specific role for HIF-1α in the pulmonary circulation is further buttressed by the observation—consistent with prior reports—that expression of HIF-1α is increased in PAECs from patients with PAH compared with control patients. Moreover, in PASMCs from patients with PAH, decreased HIF-1α activity is associated with physiologically significant increases in SMC contractility, owing to increased MLCK activity and pMLC expression. These findings support a cell-specific role for HIF-1α in the pulmonary circulation in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions. That these results are based entirely on tissue that was derived from humans with and without PAH further amplifies the significance of the present report.

Whereas evidence clearly identifies a role for HIF-1α in PH (24), the PASMC-specific role for HIF-1α in patients with PAH remains incompletely understood. Consistent with prior reports (13–15), SMC HIF-1α was found to be expressed and active in control cells under normoxic conditions. In PAECs, however, HIF-1α expression was limited in controls, but was significantly increased in patients with PAH. Although prior studies have examined HIF-1α expression in the lung in the context of PH, these studies were focused on whole lung tissue or ECs (7–9). Primary data that detail HIF-1α expression in hPASMCs remains limited. Prior reports from a haploinsufficent mouse (4) and an inducible murine model (6) suggest that HIF-1α expression in PASMCs normally potentiates the response of the pulmonary circulation to hypoxia by accentuating pulmonary vascular remodeling. In contrast, data from our laboratory indicate that the absence of HIF-1α in SMCs increases right ventricular systolic pressure in both normoxia and hypoxia (5), which suggests that HIF-1α expression in PASMCs mitigates the response to hypoxia and plays a role in maintaining the low resistance of the pulmonary circulation under normoxic conditions by constraining pMLC, thereby limiting pulmonary vascular tone. To address these divergent results, we chose to carefully evaluate HIF-1α expression and activity in PASMCs that were derived from patients with severe PAH in comparison with healthy controls.

Results from this experimental series demonstrate decreased HIF-1α expression and increased pMLC in PASMCs from patients with PAH, which links HIF-1α expression to the regulation of pulmonary vascular tone even under normoxic conditions. These data underscore the importance of post-translational HIF-1α regulation. Although gene expression levels are similar, under normoxic conditions there is significantly more HIF-1α protein in PASMCs from control patients compared with patients with PAH. Hypoxia stabilized HIF-1α in PAH-derived PASMCs. Of note, patients with PAH are generally not hypoxic, as pulmonary parenchymal function is generally well preserved even in severe PAH (25). Pharmacological inhibition of PHD activity significantly increased HIF-1α expression in PAH cells compared with control PASMCs, which suggested that augmented PHD activity is the primary mechanism for constrained HIF-1α protein expression in PAH SMCs. Moreover, PASMCs from patients with PAH demonstrate increased intracellular O2 and Asc levels, 2 cofactors that are essential for constitutive PHD activity. Asc decreased HIF-1α expression and increased PASMC contractility, which further underscored the importance of PHD activity in determining SMC contractility.

From a functional perspective, the present data point toward vasoconstriction as an important determinant of elevated PA pressure that characterizes PAH. Contractility, as measured via collagen gel contraction assays, was greater in PASMCs from patients with PAH compared with controls. Consistent with this construct, a greater number of mature focal adhesions were present in PASMCs from patients with PAH compared with controls. Gain- and loss-of-expression studies confirmed that HIF-1α expression affects contraction, with depletion substantially increasing and overexpression mitigating contraction. Our data suggest that greater MLCK activity, but not Rho kinase activity, underlies the increase in PAH SMC contractility. Furthermore, we show that loss of HIF-1α modulates MLCK activity, likely as a result of both an increase in [Ca2+]i and MLCK phosphorylation. The increase in [Ca2+]i may likely represent a change in resting membrane potential that results from decreased Kv1.5 expression in PAH SMCs. Consistent with prior reports, PAH PASMCs demonstrated a decrease in Kv1.5 expression compared with control PASMCs. Gain- and loss-of-expression studies confirmed that HIF-1α expression positively correlates with Kv1.5 expression.

Although HIF-1α mRNA expression is similar in both control and PAH cells, protein expression differs substantially. The observation that pharmacological PHD inhibition dramatically increases HIF-1α protein expression in PASMCs from patients with PAH suggests that differences in PHD activity underlie the differential protein expression. Consistent with our overall hypothesis, PAH SMCs treated with DMOG to inhibit PHD activity demonstrate decreases in both pMLC expression and SMC contractility. Conversely, exposure to Asc, a cofactor that increases PHD activity, dramatically decreases HIF-1α expression and increases pMLC expression and SMC contractility. Taken together, these findings point to a central role for cell-specific and, perhaps, disease-specific changes in PHD activity that lead to diminished HIF-1α stabilization and increased SMC contractility.

Although undertaking this line of investigation in PASMCs that were obtained from patients with and without PAH is a strength, this approach possesses intrinsic limitations. PASMCs from 6 distinct individuals with PAH were studied. Each of the patients underwent lung transplantation, a therapy that is reserved for the most severely affected patients with PAH. Patients had long-standing disease. It is entirely possible that the findings would be different if PASMCs derived from patients with new onset or less severe PAH were studied. Furthermore, whereas PASMCs were studied at low passage numbers, dedifferentiation might have nonetheless occurred. Whereas PASMCs were rigorously characterized and maintained a phenotype that was consistent with SMCs, the potential that cell culture altered the cells cannot be entirely dismissed. That said, both control and PAH cells were handled similarly. Data included in the report are derived from 6 patients with PAH and 6 control patients. Within each group, results were qualitatively similar. Moreover, data from the whole lung tissue studies were entirely consistent with the findings in PASMCs. Finally, in vitro studies included gain- and loss-of-function strategies that supported the findings in PASMCs from patients with PAH. Given these limitations, the present report details a significant, cell-specific role for HIF-1α in PASMCs in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions.

Further investigation of the cell-specific role for HIF-1α led us to examine the cell-specific roles of HIF-2α and HIF-3α. Here, we found HIF-1α to be predominantly expressed in PASMCs, HIF-2α in PAECs, and HIF-3α in pulmonary fibroblasts (Supplemental Fig. 2). In the context of PAH, HIF-1α is decreased in PASMCs, HIF-2α is increased in PAECs, and HIF-3α is decreased in fibroblasts compared with control cells (Supplemental Table 3). HIF-2α expression was minimal and HIF-3α expression undetectable in PASMCs from both control patients and patients with PAH. Of interest, HIF-1α expression was present in PASMCs from control patients even under normoxic conditions. Altogether, these results indicate that an imbalance of HIF proteins can contribute to increased vascular tone that characterizes PAH. Evidence in support of a cell- and HIF isoform-specific role in the regulation of pulmonary vascular homeostasis includes recent observations wherein constitutive HIF-2α stabilization in PAECs leads to marked vascular remodeling in murine models (11, 12). In contrast, constitutive depletion of HIF-1α in PASMCs increases pulmonary vascular tone in a murine model (5). Further evidence for an isoform-specific role is derived from a report that demonstrated that HIF-3α can repress angiogenesis by inhibiting transcription of HIF-1α target genes (26, 27).

This report outlines a novel molecular mechanism whereby PASMC HIF-1α regulates pulmonary vascular tone. In PASMCs that were isolated from control patients, we found that HIF-1α is expressed and active under normoxic conditions. Constrained HIF-1α expression in PAH SMCs likely results from augmented PHD activity. Overall outcome is an increase in PASMC pMLC and elevated pulmonary vascular tone. Thus, under physiological conditions, PASMC-specific HIF-1α plays a central role in maintaining low pulmonary vascular tone, and in PAH, decreased PASMC HIF-1α activity contributes to an elevation in vascular tone. Cell-specific modulation of HIF-1α activity might therefore represent a viable strategy to treat PH.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. A. J. Giaccia (Stanford University) for providing the HIF-1αCA construct. This research was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL060784 and HL0706280 (to D.N.C.). Tissue sections were provided by the Pulmonary Hypertensive Breakthrough Initiative (PHBI). Funding for the PHBI is provided by the Cardiovascular Medical Research and Education Fund (University of Pennsylvania, PA, USA). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- Asc

ascorbate

- DMOG

dimethyloxalylglycine

- EC

endothelial cell

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- hFGF-B

human fibroblastic growth factor-B

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducible factor-1α

- IPAH

idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension

- MHC11

smooth muscle myosin heavy chain 11

- MLC

myosin light chain

- MLCK

myosin light chain kinase

- PA

pulmonary artery

- PAEC

pulmonary artery endothelial cell

- PAH

pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PASMC

pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- PHD

prolyl hydroxylase domain

- pMLC

phosphorylated myosin light chain

- siHIF-1α

scrambled HIF-1α

- siNTC

scrambled nontargeted control

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- α-SMA

α-smooth muscle actin

- SMC

smooth muscle cell

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E. A. Barnes and D. N. Cornfield designed research; E. A. Barnes and D. N. Cornfield analyzed data; E. A. Barnes and O. Sedan performed research; E. A. Barnes and D. N. Cornfield wrote the paper; and C.-H. Chen assisted with research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benza R. L., Miller D. P., Gomberg-Maitland M., Frantz R. P., Foreman A. J., Coffey C. S., Frost A., Barst R. J., Badesch D. B., Elliott C. G., Liou T. G., McGoon M. D. (2010) Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation 122, 164–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stenmark K. R., Fagan K. A., Frid M. G. (2006) Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Circ. Res. 99, 675–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang G. L., Semenza G. L. (1995) Purification and characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1230–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu A. Y., Shimoda L. A., Iyer N. V., Huso D. L., Sun X., McWilliams R., Beaty T., Sham J. S., Wiener C. M., Sylvester J. T., Semenza G. L. (1999) Impaired physiological responses to chronic hypoxia in mice partially deficient for hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. J. Clin. Invest. 103, 691–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y. M., Barnes E. A., Alvira C. M., Ying L., Reddy S., Cornfield D. N. (2013) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells lowers vascular tone by decreasing myosin light chain phosphorylation. Circ. Res. 112, 1230–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball M. K., Waypa G. B., Mungai P. T., Nielsen J. M., Czech L., Dudley V. J., Beussink L., Dettman R. W., Berkelhamer S. K., Steinhorn R. H., Shah S. J., Schumacker P. T. (2014) Regulation of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension by vascular smooth muscle hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 189, 314–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuder R. M., Chacon M., Alger L., Wang J., Taraseviciene-Stewart L., Kasahara Y., Cool C. D., Bishop A. E., Geraci M., Semenza G. L., Yacoub M., Polak J. M., Voelkel N. F. (2001) Expression of angiogenesis-related molecules in plexiform lesions in severe pulmonary hypertension: evidence for a process of disordered angiogenesis. J. Pathol. 195, 367–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fijalkowska I., Xu W., Comhair S. A., Janocha A. J., Mavrakis L. A., Krishnamachary B., Zhen L., Mao T., Richter A., Erzurum S. C., Tuder R. M. (2010) Hypoxia inducible-factor1α regulates the metabolic shift of pulmonary hypertensive endothelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 1130–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marsboom G., Toth P. T., Ryan J. J., Hong Z., Wu X., Fang Y. H., Thenappan T., Piao L., Zhang H. J., Pogoriler J., Chen Y., Morrow E., Weir E. K., Rehman J., Archer S. L. (2012) Dynamin-related protein 1-mediated mitochondrial mitotic fission permits hyperproliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells and offers a novel therapeutic target in pulmonary hypertension. Circ. Res. 110, 1484–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ying L., Becard M., Lyell D., Han X., Shortliffe L., Husted C. I., Alvira C. M., Cornfield D. N. (2015) The transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channel modulates uterine tone during pregnancy. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 319ra204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai Z., Li M., Wharton J., Zhu M. M., Zhao Y.-Y. (2016) Prolyl-4 hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) deficiency in endothelial cells and hematopoietic cells induces obliterative vascular remodeling and severe pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice and humans through hypoxia-inducible factor-2α. Circulation 133, 2447-2458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapitsinou P. P., Rajendran G., Astleford L., Michael M., Schonfeld M. P., Fields T., Shay S., French J. L., West J., Haase V. H. (2016) The endothelial prolyl-4-hydroxylase domain 2/hypoxia-inducible factor 2 axis regulates pulmonary artery pressure in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 36, 1584–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stroka D. M., Burkhardt T., Desbaillets I., Wenger R. H., Neil D. A., Bauer C., Gassmann M., Candinas D. (2001) HIF-1 is expressed in normoxic tissue and displays an organ-specific regulation under systemic hypoxia. FASEB J. 15, 2445–2453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu A. Y., Frid M. G., Shimoda L. A., Wiener C. M., Stenmark K., Semenza G. L. (1998) Temporal, spatial, and oxygen-regulated expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in the lung. Am. J. Physiol. 275, L818–L826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad A., Ahmad S., Malcolm K. C., Miller S. M., Hendry-Hofer T., Schaack J. B., White C. W. (2013) Differential regulation of pulmonary vascular cell growth by hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-1α and hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-2α. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 49, 78–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein A. C., Gleadle J. M., McNeill L. A., Hewitson K. S., O’Rourke J., Mole D. R., Mukherji M., Metzen E., Wilson M. I., Dhanda A., Tian Y. M., Masson N., Hamilton D. L., Jaakkola P., Barstead R., Hodgkin J., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Schofield C. J., Ratcliffe P. J. (2001) C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell 107, 43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fong G. H., Takeda K. (2008) Role and regulation of prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Cell Death Differ. 15, 635–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan Y., Mansfield K. D., Bertozzi C. C., Rudenko V., Chan D. A., Giaccia A. J., Simon M. C. (2007) Multiple factors affecting cellular redox status and energy metabolism modulate hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase activity in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 912–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samizo K., Okagaki T., Kohama K. (1999) Inhibitory effect of phosphorylated myosin light chain kinase on the ATP-dependent actin-myosin interaction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 261, 95–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan X. J., Wang J., Juhaszova M., Gaine S. P., Rubin L. J. (1998) Attenuated K+ channel gene transcription in primary pulmonary hypertension. Lancet 351, 726–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pozeg Z. I., Michelakis E. D., McMurtry M. S., Thébaud B., Wu X. C., Dyck J. R., Hashimoto K., Wang S., Moudgil R., Harry G., Sultanian R., Koshal A., Archer S. L. (2003) In vivo gene transfer of the O2-sensitive potassium channel Kv1.5 reduces pulmonary hypertension and restores hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in chronically hypoxic rats. Circulation 107, 2037–2044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Remillard C. V., Tigno D. D., Platoshyn O., Burg E. D., Brevnova E. E., Conger D., Nicholson A., Rana B. K., Channick R. N., Rubin L. J., O’connor D. T., Yuan J. X. (2007) Function of Kv1.5 channels and genetic variations of KCNA5 in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C1837–C1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonnet S., Rochefort G., Sutendra G., Archer S. L., Haromy A., Webster L., Hashimoto K., Bonnet S. N., Michelakis E. D. (2007) The nuclear factor of activated T cells in pulmonary arterial hypertension can be therapeutically targeted. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 11418–11423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Formenti F., Beer P. A., Croft Q. P., Dorrington K. L., Gale D. P., Lappin T. R., Lucas G. S., Maher E. R., Maxwell P. H., McMullin M. F., O’Connor D. F., Percy M. J., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J., Smith T. G., Talbot N. P., Robbins P. A. (2011) Cardiopulmonary function in two human disorders of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway: von Hippel-Lindau disease and HIF-2alpha gain-of-function mutation. FASEB J. 25, 2001–2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humbert M., Morrell N. W., Archer S. L., Stenmark K. R., MacLean M. R., Lang I. M., Christman B. W., Weir E. K., Eickelberg O., Voelkel N. F., Rabinovitch M. (2004) Cellular and molecular pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43, 13S–24S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonnet S., Michelakis E. D., Porter C. J., Andrade-Navarro M. A., Thébaud B., Bonnet S., Haromy A., Harry G., Moudgil R., McMurtry M. S., Weir E. K., Archer S. L. (2006) An abnormal mitochondrial-hypoxia inducible factor-1α-Kv channel pathway disrupts oxygen sensing and triggers pulmonary arterial hypertension in fawn hooded rats: similarities to human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 113, 2630–2641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makino Y., Cao R., Svensson K., Bertilsson G., Asman M., Tanaka H., Cao Y., Berkenstam A., Poellinger L. (2001) Inhibitory PAS domain protein is a negative regulator of hypoxia-inducible gene expression. Nature 414, 550–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.