Significance

Hydroperoxides play central roles in cell signaling. Hydroperoxides of arachidonic acid are mediators of inflammatory processes in mammals, whereas hydroperoxides of linoleic acid play equivalent roles in plants. Peroxynitrite is also involved in host–pathogen interactions, and hydroperoxide levels must therefore be strictly controlled by host-derived thiol-dependent peroxidases. Organic hydroperoxide resistance (Ohr) enzymes, which are present in many bacteria, display unique biochemical properties, reducing fatty acid hydroperoxides and peroxynitrite with extraordinary efficiency. Furthermore, Ohr (but not other thiol-dependent peroxidases) is involved in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa response to fatty acid hydroperoxides and to peroxynitrite, although the latter is more complex, probably depending on other enzymes. Therefore, Ohr plays central roles in the bacterial response to two hydroperoxides that are at the host–pathogen interface.

Keywords: hydroperoxides, thiols, Cys-based peroxidase, pathogenic bacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Abstract

Organic hydroperoxide resistance (Ohr) enzymes are unique Cys-based, lipoyl-dependent peroxidases. Here, we investigated the involvement of Ohr in bacterial responses toward distinct hydroperoxides. In silico results indicated that fatty acid (but not cholesterol) hydroperoxides docked well into the active site of Ohr from Xylella fastidiosa and were efficiently reduced by the recombinant enzyme as assessed by a lipoamide-lipoamide dehydrogenase–coupled assay. Indeed, the rate constants between Ohr and several fatty acid hydroperoxides were in the 107–108 M−1⋅s−1 range as determined by a competition assay developed here. Reduction of peroxynitrite by Ohr was also determined to be in the order of 107 M−1⋅s−1 at pH 7.4 through two independent competition assays. A similar trend was observed when studying the sensitivities of a ∆ohr mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa toward different hydroperoxides. Fatty acid hydroperoxides, which are readily solubilized by bacterial surfactants, killed the ∆ohr strain most efficiently. In contrast, both wild-type and mutant strains deficient for peroxiredoxins and glutathione peroxidases were equally sensitive to fatty acid hydroperoxides. Ohr also appeared to play a central role in the peroxynitrite response, because the ∆ohr mutant was more sensitive than wild type to 3-morpholinosydnonimine hydrochloride (SIN-1 , a peroxynitrite generator). In the case of H2O2 insult, cells treated with 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (a catalase inhibitor) were the most sensitive. Furthermore, fatty acid hydroperoxide and SIN-1 both induced Ohr expression in the wild-type strain. In conclusion, Ohr plays a central role in modulating the levels of fatty acid hydroperoxides and peroxynitrite, both of which are involved in host–pathogen interactions.

Thiol peroxidases are receiving increasing attention as biological sensors and signal transducers of hydroperoxide-dependent pathways (1–3). Peroxiredoxin (Prx) and glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) are central players in hydroperoxide metabolism and sensing, which is consistent with their high overall abundance and reactivity (3).

The issue of substrate specificity in Cys-based peroxidases is intriguing. Prx enzymes are highly reactive to hydroperoxides but not to other oxidants or thiol reagents, such as chloroamines or iodoacetamide (4). The structural features responsible for this phenomenon are still emerging (5–7), including some more subtle aspects of their specificity. For instance, the three different Prxs from Mycobacterium tuberculosis display distinct hydroperoxide specificities with alkyl hydroperoxide reductase E (AhpE) being highly specialized toward long-chain fatty acid hydroperoxides (8). Furthermore, yeast Tsa1, yeast Tsa2, rat Prx6, and human Prx2 are more reactive toward H2O2 (9–11), whereas human Prx5 is more reactive toward organic hydroperoxides and peroxynitrite (12, 13).

Organic hydroperoxide resistance (Ohr) and osmotically inducible protein C (OsmC) form another group of Cys-based peroxidases that are biochemically and structurally distinct from Prx and Gpx. Ohr was first described in Xanthomonas campestris, through the characterization of a null mutant strain (∆ohr). The ∆ohr strain displays high sensitivity toward tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP), but not to H2O2. Moreover, transcription of the ohr gene is specifically induced by t-BHP (14). Later on, this enzyme was found in several bacteria (15). Subsequently, we and others were able to show that this “organic hydroperoxide resistance” phenotype is due to the Cys-based, thiol-dependent peroxidase activity of Ohr (16, 17). In contrast, OsmC proteins were initially implicated in the osmotic stress response (18), and only later were shown to share structural and biochemical similarities with Ohr (19, 20). Ohr/OsmC enzymes present an α/β-fold that is very distinct from the thioredoxin-fold characteristic of Prx and Gpx (17, 21, 22). Furthermore, Ohr/OsmC enzymes accept electrons from lipoyl groups of proteins (23, 24) in contrast to Prx and Gpx, which are most commonly reduced by thioredoxin or glutaredoxin/glutathione (GSH) (1, 2).

Despite all of these studies, the identification of the natural oxidizing substrates of Ohr is still a challenge. It is known that the Ohr from Xylella fastidiosa (XfOhr) is 10,000-fold more efficient in the removal of t-BHP compared with H2O2 (23). However, because t-BHP and cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) are artificial compounds, the identity of the biological oxidizing substrates for Ohr remains to be identified. We previously raised the hypothesis that elongated hydrophobic molecules, such as hydroperoxides derived from fatty acids, could be the natural substrates, because these compounds fitted very well into the electron density corresponding to a PEG molecule found bound to the active site of Ohr in the crystal structure (22). Other corroborating evidence came from the observation that the Ohr and its transcriptional repressor (OhrR) system are responsible for linoleic acid hydroperoxide (LAOOH) clearance in Xanthomonas spp. (25). Furthermore, LAOOHs induce ohr transcription, at higher levels than t-BHP in some cases (25–27).

Here, we systematically investigated the involvement of Ohr in the bacterial response toward distinct hydroperoxides. Initially, using different approaches, we showed that XfOhr preferentially reduced long-chain fatty acid hydroperoxides and also peroxynitrite. Furthermore, microbiological assays using Pseudomonas aeruginosa correlated well with the biochemical/kinetic assays. Taken together, our results indicated that Ohr protein is central to the response of the bacterium to fatty acid hydroperoxides and peroxynitrite, although the process appears to be more complex in the latter case, possibly involving the cooperation of other enzymes. In contrast, catalase is a central player in the response of P. aeruginosa to exogenously added H2O2. The experimental approach presented herein allows defining the relative sensing and detoxifying roles of various peroxidatic systems in bacteria challenged with different biologically relevant hydroperoxides.

Results

Fatty Acid Hydroperoxides Dock into the Ohr Active Site.

Previous data suggested that the active site cavity of XfOhr preferentially accommodates elongated molecules (22). Motivated by this observation, we performed an unbiased docking analysis to gain further insight into the affinity of Ohr protein for different organic hydroperoxides. The full structure of XfOhr [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1ZB8] was analyzed against all cis and trans isomers of hydroperoxides derived from mono- or polyunsaturated fatty acids (Fig. 1 A and C).

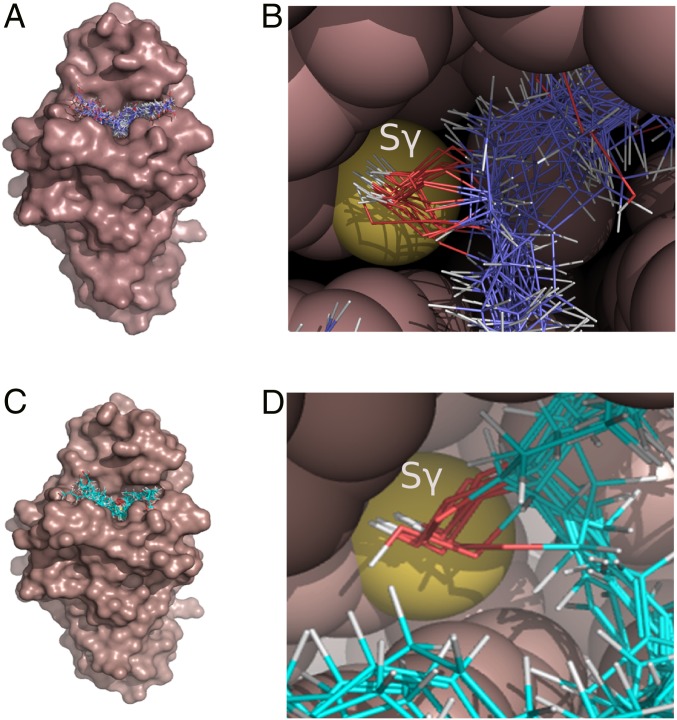

Fig. 1.

Molecular docking of long-chain hydroperoxides into the Ohr active site pocket. The molecular surface of XfOhr (PDB ID code 1ZB8) is represented in brown, whereas the hydroperoxides are shown as lines with the atoms colored as follows: carbon = purple (A and B) and cyan (C and D), oxygen = red, and hydrogen = white. (A and C) Results of docking simulations, showing the entire protein structure. Ligands used hydroperoxides derived from OAOOH, palmitoleic acid hydroperoxide, and LAOOH (A) and arachidonic acid hydroperoxide (C): 5-HpETE, 5(S)-HpETE, 8-HpETE, 9-HpETE, 12-HpETE, 15-HpETE, and 15(S)-HpETE. Oleic and linoleic acid molecules containing the hydroperoxide group in both the cis- and trans-configurations or in different combinations of the two (linoleic hydroperoxides) were considered in the analysis. (B and D) Details of the Ohr active site pocket, showing the hydroperoxide groups of the fatty acid hydroperoxides facing toward the Sγ of Cys61. The atoms of the enzyme are represented as space-filling spheres and colored brown, except for the sulfur atom of Cys61 (yellow). The docking procedures were performed using Gold software (70), and molecular graphics were generated using PyMOL (www.pymol.org/).

Long-chain fatty acid hydroperoxides docked well into the XfOhr active site, overlapping with the position occupied by a PEG molecule in the Ohr crystal structure. All of the elongated hydroperoxide molecules produced good fits with their O–O bond pointing toward the catalytic cysteine (Cys61, so-called peroxidatic Cys), although trans isomers gave higher scores (Fig. 1 B and D). However, it was not possible to observe any preferred orientation of the carboxyl group in relation to the surface of the enzyme, suggesting that hydrophobic interactions are major factors for the binding and orientation of the hydroperoxide within the active site (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1A). This finding is consistent with the fact that no systematic difference could be observed between S and R enantiomers. In the case of hydroperoxides containing more than one peroxidation, no preference for the peroxide group pointing toward Cys61 was detected. However, in stark contrast, neither the cis nor trans isomers of cholesterol hydroperoxide (ChOOH) docked well into the active site cavity (Fig. S1B). For example, the fitness scores for the docked ChOOHs, which varied between 30.1 and 47.1, were, on average, 38% lower than the fitness scores for hydroperoxides derived from arachidonic acid (54.8–67.3). This finding is all the more significant, given that the cholesterol derivatives contain more atoms; therefore, the ligand efficiency for these molecules would be even lower. For the cholesterol derivatives, the lower fitness values are probably due to the failure to orient the hydroperoxide moiety adequately toward the catalytic cysteine and/or to their rigidity, which prohibits optimizing hydrophobic interactions within the binding site cavity. These data support the hypothesis that elongated hydrophobic molecules are the preferred oxidizing substrates of Ohr proteins (22).

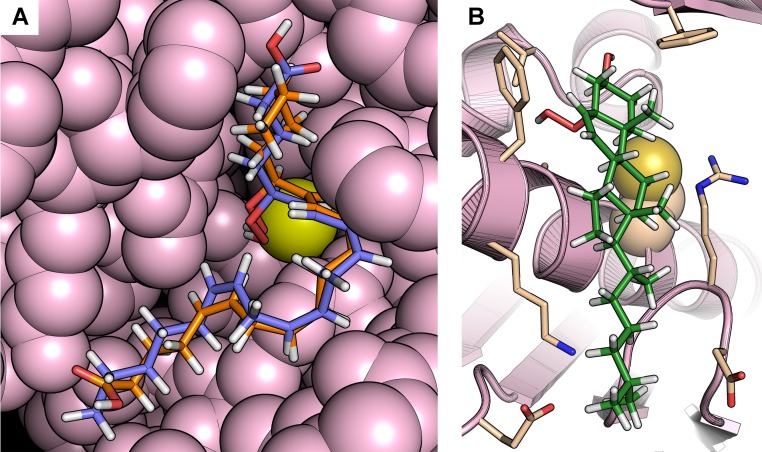

Fig. S1.

Representative docking poses. (A) Representative docking poses of 5(S)-HpETE and 15(S)-HpETE in the XfOhr active site showing great similarity in the overall conformation of the hydrocarbon chains of these arachidonic acid derivatives. In both cases, the hydroperoxide groups are positioned close to Cys61 (yellow), although their carboxyl groups are positioned on opposite sides of the active site. The atoms belonging to the enzyme are represented as spheres and colored in light pink. The 5(S)-HpETE is shown in blue, and the 15(S)-HpETE is shown in orange. (B) Docking of cholesterol-5α-hydroperoxide in the XfOhr active site. Note the hydroperoxide group faces away from Cys61 (yellow), whose side chain is represented as spheres. XfOhr is colored in light pink and represented as a cartoon. Residues within 4 Å of the cholesterol-5α-hydroperoxide molecule are colored in beige and represented as sticks, whereas cholesterol-5α-hydroperoxide itself is colored in green.

Biochemical Characterization of Peroxidase Specificity.

Next, we tested the ability of XfOhr to reduce various lipid-derived hydroperoxides to validate the docking analyses. Thiol peroxidase activity was assessed using the previously described lipoamide-lipoamide dehydrogenase–coupled assay (23). In contrast to other thiol-dependent peroxidases, lipoylated proteins (but not thioredoxin or glutathione) are the most probable physiological reductants of XfOhr and osmotically inducible protein C from Escherichia coli (EcOsmC) (23). However, alternative ways of Ohr reduction (e.g., redoxins) cannot be excluded and should be tested in the future.

Following the reduction of an artificial organic hydroperoxide (t-BHP) and applying a bisubstrate steady-state approach, it was previously determined that Ohr displays a ping-pong kinetic mechanism, and the true Km values for dihydrolipoamide and lipoylated proteins are in the 10–50 µM range (23).

A major challenge here was to establish conditions for solubilizing hydrophobic hydroperoxides without compromising the structure and activity of XfOhr. Initially, XfOhr activity was evaluated in the presence of a series of detergents and organic solvents (Fig. S2A), using a highly water-soluble organic hydroperoxide, t-BHP, as a substrate. XfOhr retained more than 80% of its original activity toward t-BHP when Tween-20 (0.25%) was used. At the same time, the activity toward LAOOH was maximal (Fig. S2B), indicating good solubilization of LAOOH (100 μM). Therefore, Tween-20 was chosen to solubilize hydrophobic hydroperoxides in the lipoamide-lipoamide dehydrogenase–coupled assays.

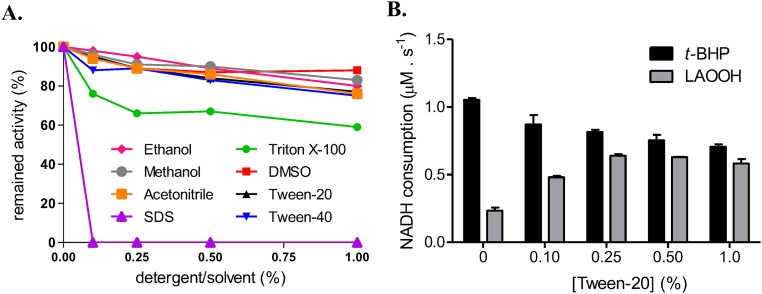

Fig. S2.

XfOhr activity in the presence of various solvents and detergents. (A) XfOhr activity was assessed by the NADH lipoamide-lipoamide dehydrogenase–coupled assay toward t-BHP, in the presence of various concentrations of solvents and detergents. One hundred percent of activity was considered the rate of NADH consumption at standard conditions (XfOhr = 0.05 μM, lipoamide dehydrogenase from X. fastidiosa (XfLpD) = 0.5 μM, dihydrolipoamide = 50 μM, t-BHP = 100 μM, and NADH = 200 μM). The results represent an arithmetic average of two independent experiments. (B) Effect of Tween-20 concentration on XfOhr activity. Reduction of t-BHP and LAOOH by XfOhr followed by the lipoamide-lipoamide dehydrogenase–coupled assay [XfOhr = 0.05 μM, XfLpD = 0.5 μM, dihydrolipoamide = 50 μM, and hydroperoxides (t-BHP and LAOOH) = 100 μM]. The assays were performed twice.

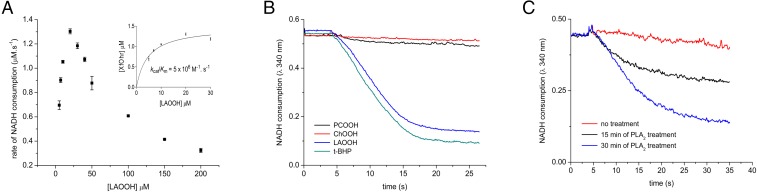

Reduction of LAOOH by XfOhr presented a complex steady-state kinetic behavior that was biphasic: At low concentrations, up to 20 μM, the rate of the reaction increased hyperbolically with increasing concentrations of LAOOH, as expected for a Michaelis–Menten model (Fig. 2A). However, above 20 μM, the rate dropped markedly as a function of LAOOH concentration (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Lipoamide-lipoamide dehydrogenase–coupled assay for the reduction of lipid hydroperoxides by XfOhr. Peroxidase activity was monitored by the consumption of NADH at 340 nm in the presence of XfOhr (0.05 μM), lipoamide dehydrogenase from X. fastidiosa (XfLpD, 0.5 μM), and lipoamide (50 μM) in sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) and DTPA (1 mM). (A) Dose-dependent reduction of LAOOH by XfOhr in the presence of Tween-20 (0.25%). (Inset) Plot of the rates of NADH oxidation, considering points up to 20-μM concentration of LAOOH. (B) Reduction of hydroperoxides (100 μM) in the presence of Triton X-100 (0.15%). PCOOH, phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxide. (C) Peroxidase activity of Ohr on PCOOH, measured after indicated time of treatment with PLA2.

Considering only the first phase (up to 20 μM), we estimated by nonlinear regression a kcat app of 36 s−1 and a Km app of 7.3 μM at 50 μM dihydrolipoamide (Fig. 2A, Inset), which indicated that XfOhr is highly efficient in the removal of LAOOH (kcat app/Km app = 5 × 106 M−1⋅s−1). However, one major limitation of this analysis was that saturation was not achieved; therefore, the kinetic parameters have probably been underestimated. Consistent with this result, we note that data for Ohr from Mycobacterium smegmatis also did not fit well to the Michaelis–Menten model at high LAOOH concentrations; however, in this case, kcat app/Km app was estimated to be in the range of 105 M−1⋅s−1 (24).

The catalytic efficiency for LAOOH was in the same range as the range previously determined for t-BHP, considering true kcat and Km values in the latter case (23). Unfortunately, the biphasic shape of the curves (Fig. 2A) does not allow us to obtain true enzymatic parameters for fatty acid hydroperoxides. Therefore, it was not possible to compare the reduction of fatty acid and artificial organic hydroperoxides on the same grounds.

We also evaluated the possibility that XfOhr could reduce hydroperoxides derived from unsaturated fatty acids attached to phosphatidylcholine, which could reflect the capacity of the enzyme to reduce hydroperoxides resident in membranes, similar to the activity described for phospholipid Gpx4 (28, 29). However, no such activity for XfOhr was detected, although it was capable of reducing both t-BHP and LAOOH in the same experiment (Fig. 2B). Moreover, when phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxide was incubated with phospholipase A2 (PLA2), releasing the corresponding free fatty acid hydroperoxide, NADH consumption was observed (Fig. 2C). Therefore, it appears that fatty acid hydroperoxides attached to phosphatidylcholine were not accessible to the XfOhr active site. Furthermore, under the same conditions, XfOhr did not reduce ChOOH (Fig. 2B), consistent with the docking analysis. In these experiments, Triton X-100 (0.15%) was used instead of Tween-20 (0.25%) to solubilize ChOOH, because this procedure results in good solubilization of this lipid (30). The products of oleic hydroperoxide (OAOOH) and LAOOH reduction by XfOhr were confirmed to be the corresponding alcohols by mass spectrometry (Fig. S3).

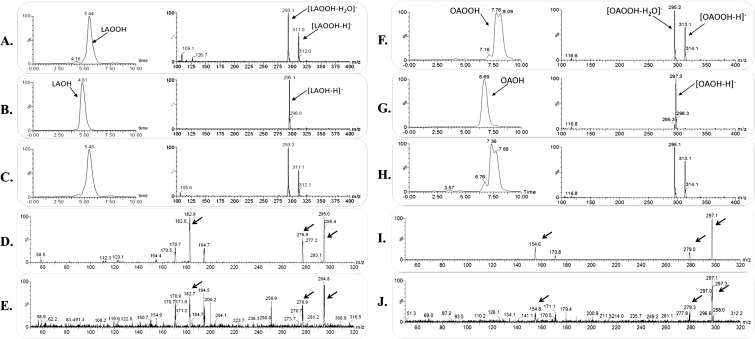

Fig. S3.

Mass spectrometry analysis of the products formed in the XfOhr reaction with LAOOH and OAOOH. (A–C) Chromatographic profile (Left) and mass spectrum (Right) of LAOOH. (A) Control, LAOOH in the absence of XfOhr. (B) Product of the reaction between XfOhr and LAOOH. (C) Product of the reaction between LAOOH and XfOhr previously alkylated with NEM. (D and E) Tandem mass spectometry (MS/MS) spectrum of the authentic linoleic acid hydroxide standard (fragment ions of m/z = 295) and for the ions formed in the Ohr reaction, respectively. (F–H) Chromatographic profile (Left) and mass spectrum (Right) of OAOOH. (F) Control reaction: OAOOH in the absence of XfOhr. (G) Product of the reaction between XfOhr and OAOOH. (H) Product of the reaction between OAOOH and XfOhr previously alkylated with NEM. (I and J) MS/MS spectrum of the authentic oleic acid hydroxide standard (fragment ions of m/z = 297) and for the ions formed in the XfOhr reaction, respectively. Arrows show similar peaks in both samples.

Regarding the non-Michaelis–Menten behavior of XfOhr at substrate concentrations higher than 20 μM (Fig. 2A), two nonexclusive hypotheses can be proposed: micelle formation of lipid hydroperoxide molecules and/or hyperoxidation of the peroxidatic cysteine of XfOhr (Cys61) to sulfinic acid (Cys-SO2H−) or sulfonic acid (Cys-SO3H−) (Fig. 3A).

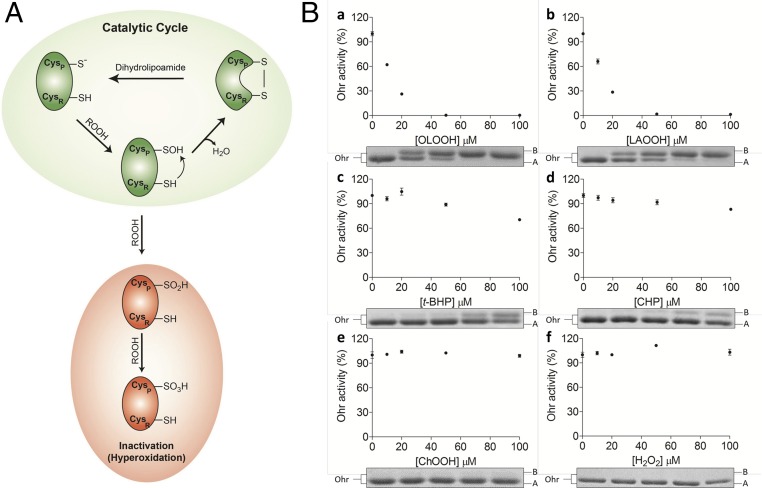

Fig. 3.

Inactivation/hyperoxidation of Ohr. (A) Schematic catalytic cycle of Ohr and its hyperoxidation: Reaction of reduced Ohr with hydroperoxides generates the peroxidatic Cys (Cysp)-SOH intermediate, which undergo condensation with resolution Cys (CysR = Cys125). This intramolecular disulfide runs faster than the reduced form in nonreducing SDS/PAGE (22). The intramolecular disulfide can be reduced back by dihydrolipoamide. In the presence of high amounts of organic hydroperoxides, Cysp-SOH can be further oxidized to Cysp-SO2H− (sulfinic acid) or Cysp-SO3H− (sulfonic acid), which comigrates with the reduced form of Ohr in SDS/PAGE. Cysp-SO2H− or Cysp-SO3H− cannot be reduced by dihydrolipoamide. (B) Oxidative inactivation/hyperoxidation of XfOhr by various hydroperoxides in the presence of 0.1% Triton X-100. Reduced XfOhr (10 μM) was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with distinct hydroperoxides at the indicated concentrations: OAOOH (a), LAOOH (b), t-BHP (c), CHP (d), ChOOH (e), and H2O2 (f). Main panels illustrate residual activity measured by the lipoamide-lipoamide dehydrogenase–coupled assay, using 200 μM t-BHP as a substrate, in the presence of 0.05 μM XfOhr, 0.5 μM lipoamide dehydrogenase from X. fastidiosa (XfLpD), and 50 μM dihydrolipoamide. Each point represents an average of triplicates, and the respective bars correspond to the SD. (Insets) Nonreducing SDS/PAGE, with each well corresponding to an aliquot of Ohr incubated with different concentrations of hydroperoxides (0, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM). In each well, 2 μg of total protein was applied.

Considering the first hypothesis, the critical micelle concentration (CMC) lies in the range of 6–60 µM for most unsaturated fatty acids, depending on pH and the counter-cation used (31–34), which is consistent with the inflection point of 20 μM (Fig. 2A). However, Tween-20 was present at a 0.25% concentration, which appears to solubilize LAOOH, at least up to a 100-μM concentration (Fig. S2B).

So, we investigated if hyperoxidation could be involved in the second phase decay (Fig. 2A). Among Cys-based peroxidases, it is well known that sulfenic acid (Cys-SOH) formed in the peroxidatic Cys can have two fates: (i) disulfide formation through a condensation reaction toward a second Cys residue or (ii) hyperoxidation to sulfinic acid and sulfonic acid due to a reaction with a second or third hydroperoxide molecule, respectively (Fig. 3A). Because sulfinic acid and sulfonic acid are not reducible by dihydrolipoamide, such reactions would result in XfOhr inactivation and could explain the rate drop at concentrations above 20 μM LAOOH (Fig. 2A).

We next evaluated the remaining activity of XfOhr after treatment with several hydroperoxides in the presence of Triton X-100 (Fig. 3B) or Tween-20 (Fig. S4). In the conditions used, t-BHP and CHP (Fig. 3B, c and d) inactivated XfOhr only slightly. In contrast, fatty acid hydroperoxides (OAOOH and LAOOH) inactivated XfOhr at very low concentrations (Fig. 3B, a and b), whereas H2O2 and ChOOH did not affect this peroxidase (Fig. 3B, e and f).

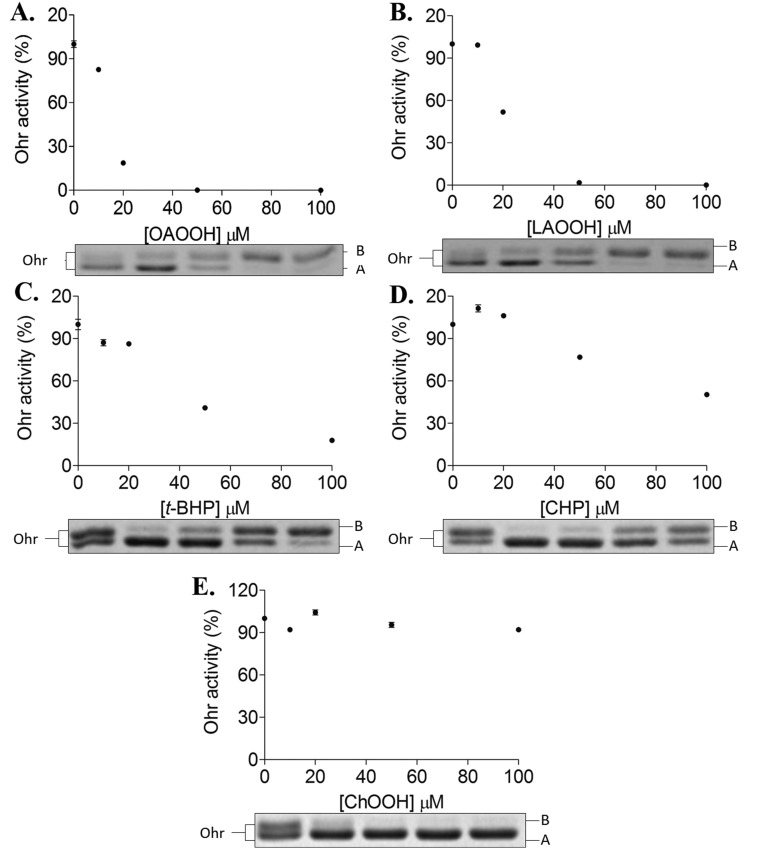

Fig. S4.

Oxidative inactivation of XfOhr by various hydroperoxides in the presence of 0.25% of Tween-20. Reduced XfOhr (10 μM) was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with distinct hydroperoxides at the indicated concentrations: OAOOH (A), LAOOH (B), t-BHP (C), CHP (D), and ChOOH (E). Main panels show residual activity measured by the lipoamide-lipoamide dehydrogenase–coupled assay, using 200 μM t-BHP as a substrate, in the presence of 0.05 μM XfOhr, 0.5 μM lipoamide dehydrogenase from X. fastidiosa (XfLpD), and 50 μM dihydrolipoamide. Each point represents an average of triplicates, and the respective bars correspond to the SD. (Insets) Nonreducing SDS/PAGE, with each well corresponding to an aliquot of Ohr incubated with different concentrations of hydroperoxides (0, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM). In each well, 2 μg of total protein was applied.

In parallel, the same samples were also analyzed by nonreducing SDS/PAGE and the pattern of XfOhr inactivation by various hydroperoxides correlated to its oxidation state (Fig. 3B, Lower and Fig. S4, Lower). Previously, we have characterized in detail by mass spectrometry the XfOhr oxidation states corresponding to each one of the bands (22). The intramolecular disulfide form of XfOhr has a lower hydrodynamic volume, and consequently runs faster (band A), than the reduced and overoxidized forms (band B) of the enzyme (Fig. 3B, Lower and Fig. S4, Lower). Hyperoxidation (assessed by appearance of band B) could only be observed in conditions where some inactivation was observed (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4).

Inadvertently, Triton X-100 (Fig. 3B, Lower) or Tween-20 (Fig. S4, Lower) provoked oxidation of XfOhr to the intramolecular disulfide form, even with no addition of hydroperoxide. This oxidation might be related to the partial structural loss of XfOhr due to the detergent treatment (Fig. 2A, Inset and Fig. S2). Another possible explanation is that traces of hydroperoxides present in detergents could have provoked the oxidation of XfOhr (35).

For ChOOH, no evidence of a reaction was obtained. These data agree well with the docking analysis (Fig. 1). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that ChOOH could not access the XfOhr active site, because this molecule can form micelles. Indeed, the parental compound (cholesterol) presents very a low CMC (25–40 nM) (36). On the other hand, because Triton X-100 and Tween-20 at least partly solubilize ChOOH (30), our results (Fig. 3B, Lower and Fig. S4, Lower) suggested that this hydroperoxide is not a good substrate for XfOhr. Also, H2O2 did not inactivate or hyperoxidize XfOhr in the analyzed conditions (Fig. 3B), consistent with the low reactivity previously described (22, 23).

For other Cys-based peroxidases, substrate specificity correlates well with hyperoxidation rates (8, 37–39), which is consistent with the fact that oxidation to Cys-SOH and hyperoxidation are both reactions dependent on hydroperoxide concentration (Fig. 3A). Noteworthy, E. coli Tpx also displays biphasic Michaelis–Menten curves with major hyperoxidation by fatty acid hydroperoxides at concentrations above 10 μM, and H2O2 is again a poor substrate (37).

Therefore, considering the amount of hydroperoxide that provokes 10% Ohr inactivation, we estimated that the reactivity of XfOhr to tested compounds increased in the following order: H2O2 <<<< CHP < t-BHP < LAOOH ∼ OAOOH (Table 1). These data are also consistent with the idea that fatty acid hydroperoxides are the preferred substrates for Ohr proteins.

Table 1.

Parameters related to hydroperoxide reduction by Ohr

| Hydroperoxide | kobs, M−1⋅s−1 | Oxidative inactivation, μM | MICwt/MIC∆ohr* |

| AhpE/Ohr competition | ∼IC10† | Extent of inhibition | |

| H2O2 | (3.0 ± 0.6) × 103 | >100 | 1 |

| LAOOH | (6.3 ± 1.7) × 107 | 1 | >10 |

| OAOOH | (4.5 ± 3.5) × 108 | 1 | >10 |

| 5(S)-HpETE | (2.6 ± 1.2) × 107 | ND | ND |

| 15(S)-HpETE | (6.0 ± 3.0) × 107 | ND | ND |

| ChOOH | — | >100 | 1 |

| t-BHP | 2.0 × 106‡ | 100 | 3 |

| ONOOH | (2 ± 0.3) × 107 | ND | — |

| CHP | ND | 100 | 3 |

kobs, observed rate constant; ND, not determined.

Ratio of MICwt (minimal concentration of hydroperoxide that inhibits growth of wild-type strain) to MIC∆ohr (minimal concentration of hydroperoxide that inhibits growth of ∆ohr strain).

Defined here as the amount of hydroperoxide that provokes 10% Ohr inactivation.

Because Ohr is several orders of magnitude more efficient than MtAhpE in the reduction of t-BHP, it was not possible to determine this rate constant through the competitive assay. Instead, data from the study by Cussiol et al. (23) were added here.

Competition and Fast Kinetics Assays on the Oxidation of Ohr.

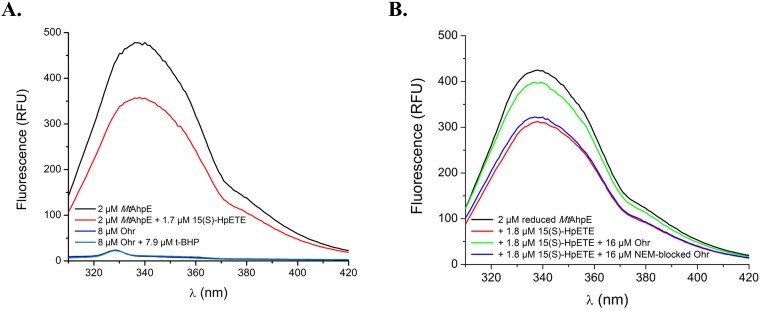

Next, we pursued the determination of the rate constants for the reactions between XfOhr and various hydroperoxides. This task is not simple because there are not many assays for organic hydroperoxides in comparison to the tools available for peroxynitrite and H2O2. Therefore, we developed a competitive assay between XfOhr and AhpE from M. tuberculosis (MtAhpE) for distinct hydroperoxides, monitoring the intrinsic fluorescence of MtAhpE (further details are provided in Materials and Methods) and taking advantage of the fact that XfOhr and Ohr from P. aeruginosa (PaOhr) lack Trp residues, and therefore present no such intrinsic fluorescence when excited at 295 nm (Fig. S5A).

Fig. S5.

Intrinsic fluorescence of MtAhpE. (A) Intrinsic fluorescence of MtAhpE and XfOhr in their reduced (represented in black and blue lines, respectively) and oxidized (red and green lines, respectively) states. (B) Emission spectra of MtAhpE (2 μM) in the reduced (black line) or oxidized (red line) state by 15(S)-HpETE (1.8 μM) or in the presence of native (green line) or NEM alkylated (blue line) XfOhr (16 μM). RFU, relative fluorescence units.

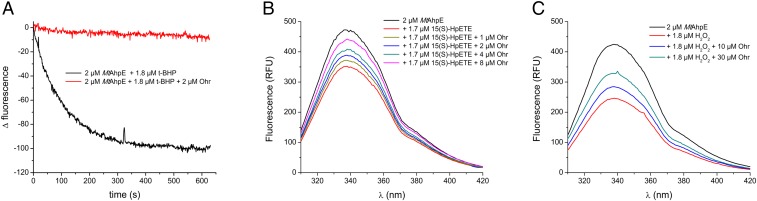

To validate this AhpE/Ohr competitive assay, we first investigated t-BHP, because the corresponding rate constants are already known for both Cys-based peroxidases. For instance, the rate constant for the reaction between t-BHP and MtAhpE is quite low, 8 × 103 M−1⋅s−1 (8), compared with the corresponding value for XfOhr and t-BHP, which is two to three orders of magnitude higher (23). As expected, XfOhr strongly inhibited the drop in MtAhpE fluorescence induced by t-BHP (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

AhpE/XfOhr competitive assay for distinct hydroperoxides. Reactions were carried out in potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM) and DTPA (50 μM), pH 7.4, at 25 °C. (A) MtAhpE (2 μM) and t-BHP (1.8 μM) in the presence (red line) or absence (black line) of XfOhr (2 μM). (B) Emission spectrum of MtAhpE (2 μM) in the reduced state (black) and after oxidation by 1.7 μM 15(S)-HpETE (red). To the reaction mixture represented by the red line, XfOhr was added at the following concentrations: 1.0 μM (brown), 2.0 μM (blue), 4.0 μM (green), and 8.0 μM (purple). (C) Emission spectrum of AhpE (2 μM) in the reduced state (black) and after oxidation by 1.8 μM hydrogen peroxide (red). To the reaction mixture represented by red line, XfOhr was added at the following concentrations: 10.0 μM (blue) and 30.0 μM (green). RFU, relative fluorescence units.

We went on to evaluate the competition between XfOhr and MtAhpE for several organic hydroperoxides. As an illustrative example, we show here the competition of the two Cys-based peroxidases for 15-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid [15(S)-HpETE], an arachidonic acid hydroperoxide. Reduced XfOhr inhibited the decrease of MtAhpE fluorescence caused by 15(S)-HpETE in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4B), and the second-order rate constant between XfOhr and 15(S)-HpETE was determined to be 6 ± 3 × 107 M−1⋅s−1. As anticipated, XfOhr previously alkylated with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) completely lost its ability to inhibit MtAhpE oxidation (Fig. S5B).

A second example is the competition between the two peroxidases for H2O2, considering that the rate constant of MtAhpE for H2O2 is 8.1 × 104 M−1⋅s−1 (8). We observed that only at very high concentrations (10–30 μM) was XfOhr able to inhibit MtAhpE (2 μM) oxidation (Fig. 4C). The rate constant of the reaction between XfOhr and H2O2 was estimated to be 3.0 ± 0.6 × 103 M−1⋅s−1. Once again, XfOhr blocked with NEM lost its capacity to compete with MtAhpE for H2O2. Previously, by a steady-state approach (the lipoamide-lipoamide dehydrogenase–coupled assay), we determined that the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of XfOhr for H2O2 was (2.3 ± 0.2) × 102 M−1⋅s−1 (23).

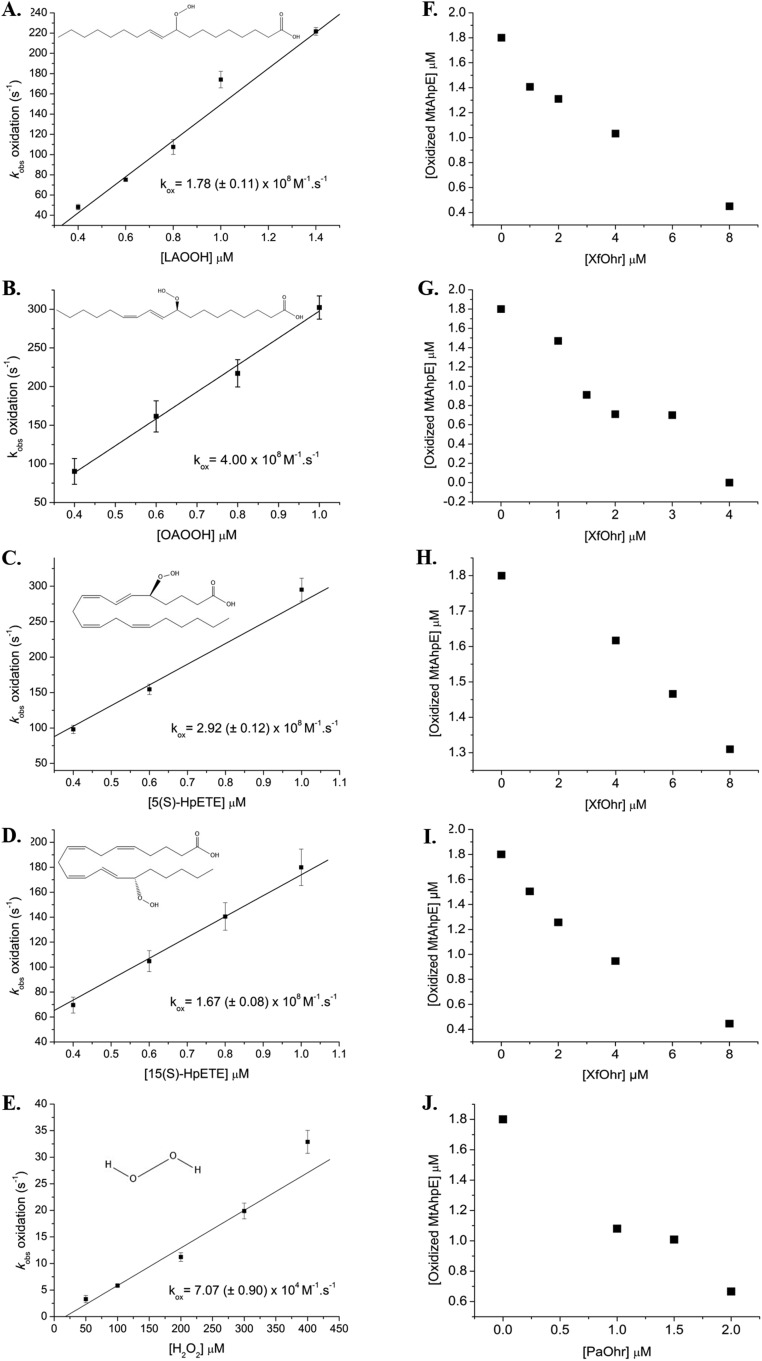

This Ohr/AhpE competition assay was performed for several hydroperoxides of distinct chemical structures (Fig. S6), and it was possible to establish the respective rate constants (Table 1). PaOhr was also assessed using this competitive assay, and essentially the same results were obtained as for the enzyme from X. fastidiosa. For instance, the second-order rate constant between OAOOH and PaOhr is also in the range of 108 M−1⋅s−1 (Fig. S6J).

Fig. S6.

AhpE/Ohr competition assay. Plots of kobs of MtAhpE oxidation by LAOOH (A), OAOOH (B), 5(S)-HpETE (C), 15(S)-HpETE (D), and H2O2 (E). kox, second-order rate constant for the oxidation of MtAhpE by various peroxides. Total fluorescence was measured at fluorescence intensity (λex) of 280 nm using 0.2 μM MtAhpE. Chemical structures of hydroperoxides were obtained from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. Effects of increasing concentration of XfOhr on MtAhpE oxidation by LAOOH (F), OAOOH (G), 5(S)-HpETE (H), and 15(S)-HpETE (I). (J) Effect of increasing concentration of PaOhr on MtAhpE oxidation by OAOOH.

Once again, the same trend was observed: Ohr proteins displayed higher reactivity toward hydroperoxides with an elongated shape and hydrophobic properties. However, it was not possible to determine the rate constant for the reaction between XfOhr and ChOOH because the intrinsic fluorescence of MtAhpE did not change upon treatment with this oxidant. One exception was peroxynitrite, which is described below.

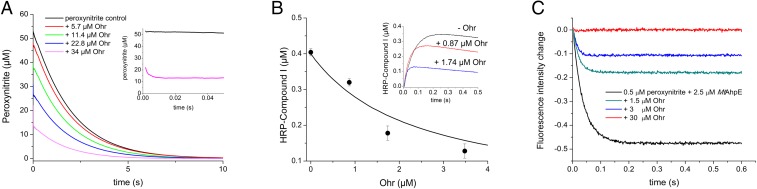

Reactivity of XfOhr Toward Peroxynitrite.

Pathogens can be exposed to peroxynitrite during host–pathogen interactions (40–42). Because the reactivity of Ohr proteins toward peroxynitrite has not been hitherto reported, this analysis was performed here. Reduced XfOhr caused peroxynitrite to decay faster, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). The reaction was so rapid that it precluded the determination of the rate constant by this direct approach. Rather, the rate constant was determined by two independent competitive assays against HRP (11) or against MtAhpE (as described above). XfOhr at concentrations considerably lower than HRP (10 μM) inhibited the formation of compound I by peroxynitrite (0.4 μM) (Fig. 5B). From the dose–response effect of XfOhr on peroxynitrite-mediated HRP compound I formation, an apparent rate constant of (1.2 ± 0.4) × 107 M−1⋅s−1 at pH 7.4 and 25 °C was determined (Fig. 5B, Inset).

Fig. 5.

Peroxynitrite reduction by XfOhr. Reactions were carried out in potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM), DTPA (100 μM), pH 7.4, at 25 °C. (A) Peroxynitrite (50 μM) was rapidly mixed with reduced Ohr at increasing concentrations, and oxidant decay was followed by its intrinsic absorbance at 310 nm. (B) Peroxynitrite (0.4 μM) was mixed with HRP (10 μM) in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of reduced Ohr. HRP-compound I formation was monitored at the Soret band. The line represents the expected results simulated using the Gepasi program (76), and considering a simple competition between reduced XfOhr and HRP for peroxynitrite, a rate constant of HRP-mediated peroxynitrite reduction of 2.2 × 106 M−1⋅s−1 and a rate constant of XfOhr-mediated peroxynitrite reduction of 1.2 × 107 M−1⋅s−1, calculated according to Eq. 1. (Inset) Time course of compound I formation by the reaction of HRP (10 μM) with peroxynitrite (0.4 μM) in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of reduced Ohr. (C) Peroxynitrite (0.5 μM) was mixed with reduced MtAhpE (2.5 μM) in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of reduced XfOhr, and MtAhpE oxidation was followed by its total intrinsic fluorescence decrease (λ = 295 nm).

As an alternative, we also analyzed the competition between MtAhpE and XfOhr for peroxynitrite. Peroxynitrite (0.5 μM) caused a rapid decrease in total fluorescence intensity (λex = 295 nm) of reduced MtAhpE (2.5 μM). The exponential fitting of the experimental curve was consistent with a rate constant of peroxynitrite-mediated MtAhpE oxidation of 1.1 × 107 M−1⋅s−1 at pH 7.4 and 25 °C, in close agreement to the previously reported value (8). Reduced XfOhr dose-dependently inhibited the decrease in fluorescence of MtAhpE caused by peroxynitrite, consistent with a rate constant between peroxynitrite and XfOhr of (2.0 ± 0.3) ≥ 107 M−1⋅s−1 at pH 7.4 and 25 °C (Fig. 5C). Therefore, XfOhr reduces not only fatty acid hydroperoxides but also peroxynitrite, with extraordinarily high rates.

In Vivo Characterization of Ohr Sensitivities Toward Various Hydroperoxides.

We aimed to investigate if these results on substrate specificity correlate to bacterial responses toward distinct hydroperoxides. For this purpose, we used P. aeruginosa, which produces surfactants and secretes lipases, allowing it to solubilize and take up very hydrophobic compounds (43).

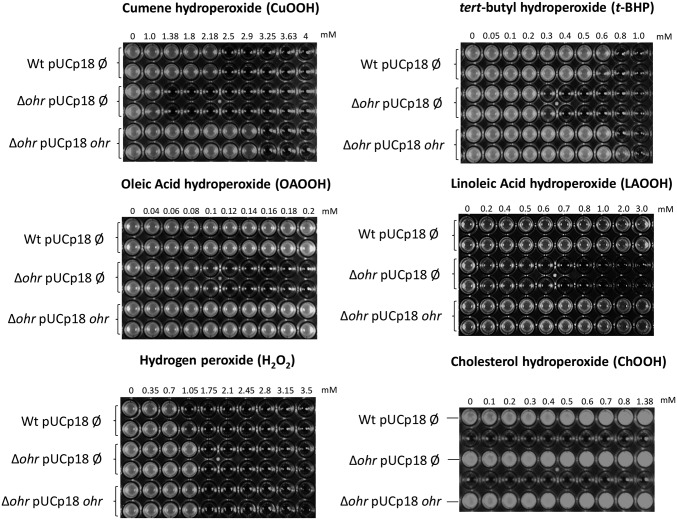

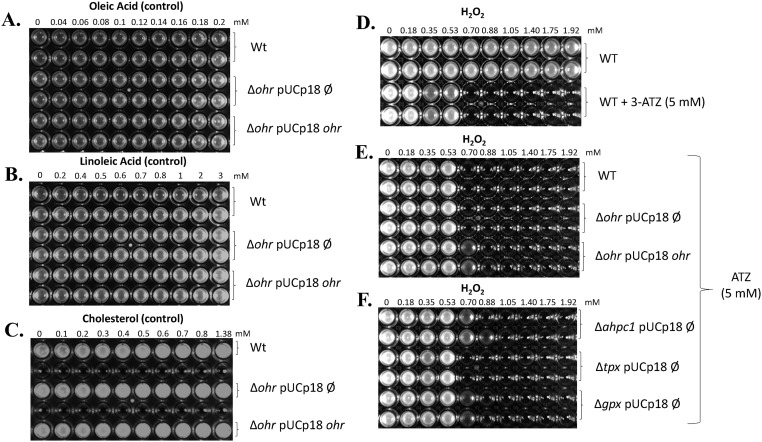

The sensitivities of Δohr and wild-type strains were comparatively analyzed by the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay against various hydroperoxides. Interestingly, none of the lipid hydroperoxides in the concentration range studied here (OAOOH, LAOOH, and ChOOH) inhibited the growth of the wild-type strain, whereas H2O2, t-BHP, and CHP did (Fig. 6). As expected, the Δohr strain presented a reduced capacity to grow in the presence of either artificial (CHP and t-BHP) or fatty acid hydroperoxides compared with the wild type (Fig. 6). It is noteworthy that the extent of inhibition (defined here as MICwild-type strain/MICΔohr strain) for OAOOH and LAOOH (more than 10-fold) was considerably greater than a similar parameter for artificial hydroperoxides (around threefold for t-BHP and CHP). For H2O2, the MIC was the same for the wild-type and Δohr strains (Table 1) and ChOOH did not inhibit the growth of either. These results indicated once again that fatty acid hydroperoxides are the best substrates for Ohr proteins, which correlates well with the original docking analysis (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1), the inactivation assay data (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4), and the second-order rate constant (k) values (Table 1). As important controls, the phenotypes of the Δohr strain were complemented in trans (pUCp18 plasmid) with the ohr gene from P. aeruginosa (LN04 strain) with the restoration of the wild-type resistance to hydroperoxides (Fig. 6). These controls unequivocally indicated that the observed sensitivities were due to the ohr gene deletion. Furthermore, nonoxidized lipids did not kill either wild-type or Δohr strains (Fig. S7 A–C), indicating that the hydroperoxide moiety in the carbon backbone was fundamental for inducing cell death.

Fig. 6.

Susceptibility of ∆ohr P. aeruginosa strain to various hydroperoxides. The MIC assay was performed to assess the sensitivities of P. aeruginosa strains to distinct hydroperoxides: pUCp18 Ø is an empty vector, and pUCp18 ohr is a vector for expression of ohr from P. aeruginosa. The concentrations of hydroperoxides used are described above each panel. Plates were incubated at 37 °C under agitation (200 rpm), and the results were observed after 16 h. MIC assays were done in biological triplicates, each one with two technical replicates. All hydroperoxides were dissolved in DMSO, with the exception of ChOOH, which was dissolved in isopropyl alcohol. As control experiments, the same assays were performed with 5% DMSO or 5% isopropyl alcohol only or with the respective fatty acid or cholesterol dissolved in DMSO and isopropyl alcohol, respectively, and no loss of viability were observed. Wt, wild type.

Fig. S7.

Response of ohr mutant of P. aeruginosa to oleic acid (A), linoleic acid (B), and cholesterol (C). Wt, wild type. These experiments are the controls for the MIC assay depicted in Fig. 6, using parental fatty acids. All lipids were dissolved in 5% DMSO, with exception of cholesterol, which was dissolved in 5% isopropyl alcohol. (D–F) Effect of 3-ATZ treatment on response of wild-type (WT) and single-mutant P. aeruginosa cells (Δohr, ΔahpC1, Δtpx, and Δgpx) toward H2O2 challenge. WT denotes the PA14 wild-type strain, pUCp18 Ø denotes the empty pUC18 plasmid, and pUCp18 ohr denotes the plasmid with the ohr gene. Plates were incubated at 37 °C under agitation (200 rpm), and the results were observed after 16 h. MIC assays were done in biological triplicates, each one with two technical replicates. The concentrations of H2O2 used are described above the panels.

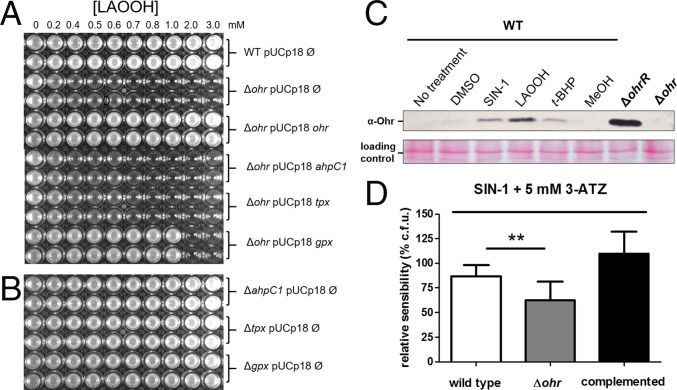

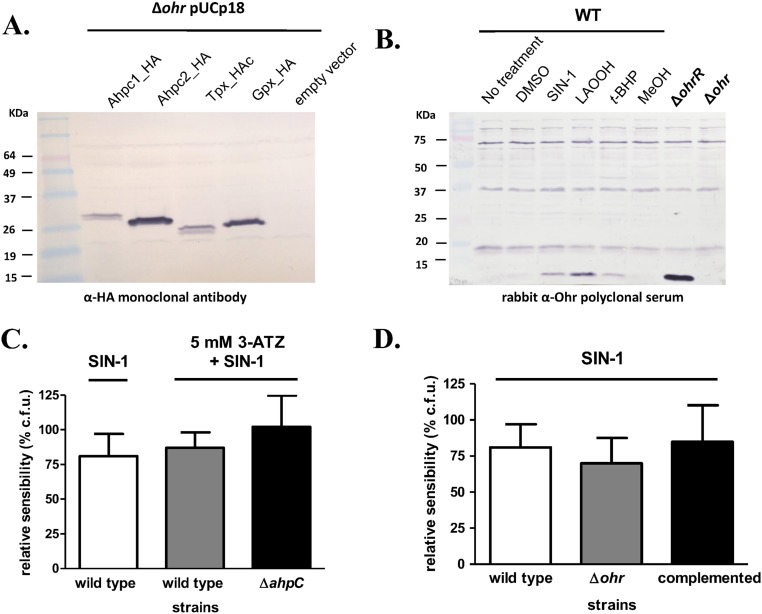

The response of P. aeruginosa to fatty acid hydroperoxides was further investigated by analyzing other mutants to thiol-dependent peroxidases. Remarkably, among all mutants, only ∆ohr displayed sensitivity to LAOOH (Fig. 7 A and B), indicating the PaOhr is essential to the protection of P. aeruginosa to this insult. Furthermore, the Δohr strain transformed with genes for other thiol-dependent peroxidases did not recover the wild-type phenotype. For example, Gpx expression in the Δohr background only partially restored the resistance to LAOOH treatment (Fig. 7A). Expression of thiol-dependent peroxidases in the Δohr background was ascertained by Western blot (Fig. S8A). Finally, as expected for a gene central to the bacterial response to fatty acid hydroperoxides, treatment with LAOOH led to higher levels of ohr induction than did t-BHP (Fig. 7C and Fig. S8B). For comparison purposes, we also show here that the expression of the ohr gene in the ΔohrR background was maximal, because the repression by the transcription factor OhrR was absent (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Response of P. aeruginosa to LAOOH and peroxynitrite. pUCp18 Ø is an empty vector, and pUCp18 ohr, ahpC1, tpx, and gpx from P. aeruginosa are vectors for ohr, ahpC1, tpx, and gpx expression, respectively. (A and B) MIC assay to assess the sensitivities of P. aeruginosa strains deficient for Cys-based peroxidases to LAOOH. (C, Upper) Western blot for Ohr expression in P. aeruginosa using an antibody against Ohr from X. fastidiosa. (C, Lower) Ponceau S was used as a loading control. Cells were exposed to SIN-1 (1 mM), DMSO (5%), LAOOH (50 μM), t-BHP (200 μM), and MeOH (5%) for 30 min at 37 °C. WT, wild type. (D) Colony count assay to assess the sensitivities of P. aeruginosa strains to SIN-1 (3 mM). In all cases, cells were treated with ATZ (5 mM), a catalase inhibitor, 10 min before cells were challenged with SIN-1 (3 mM) for 30 min at 37 °C. The bars represent the means of the colony formation unit (c.f.u.) percentage relative to the sensitivity of cells treated with DMSO (5%) + 3-ATZ (5 mM) plus SD. The Δohr mutant was statistically more sensitive than the wild-type strain (**P < 0.05, unpaired t test; n = 8). WT, wild type.

Fig. S8.

P. aeruginosa response to peroxides. (A) Control of expression of AhpC1, AhpC2, Tpx, and Gpx in Δohr background. All expressed proteins shown here were tagged with human influenza hemagglutinin (HA), which allowed us to check their expression. These strains were used in the assays shown in Fig. 7A. (B) Whole membrane from experiment depicted in Fig. 6C. Because Ohr proteins present high structural conservation, rabbit polyclonal serum raised against Ohr from X. fastidiosa was able to detect PaOhr in P. aeruginosa extracts. The nonspecific bands detected here are an inherent characteristic of polyclonal sera and were also detected in the Δohr background. (C) Catalase inhibitor (ATZ) did not affect the sensitivity of the wild-type strain to SIN-1 treatment (white and gray bars). In the same way, the ΔahpC mutant did not present sensibility to SIN-1 even in the presence of 3-ATZ (n = 7 for each tested strain). For catalase inhibition, 3-ATZ (5 mM) was added 10 min before cells were challenged with SIN-1 (3 mM) for 30 min at 37 °C. (D) The Δohr mutant was not statistically more sensitive than wild-type strain to the SIN-1 (3 mM) treatment (P < 0.05, unpaired t test; n = 7). Bars represent the means of colony formation unit (c.f.u.) percentages relative to the sensitivity of cells treated with DMSO (5%) plus SD.

In contrast to the LAOOH insult, the response of P. aeruginosa to exogenous H2O2 was highly dependent on catalase, because increased sensitivity toward the wild-type strain was only detected in cells treated with 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (ATZ), a catalase inhibitor (Fig. S7 D–F). This observation is in agreement with studies in E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and Francisella tularensis, where catalase enzymes are preponderant in the defense against exogenous H2O2 (44–47).

The response of P. aeruginosa to peroxynitrite is more difficult to investigate, in part, due to the intrinsic instability of this hydroperoxide. In this case, we had to use a distinct assay, different from MIC, by exposing the bacterium to 3-morpholinosydnonimine hydrochloride (SIN-1, a peroxynitrite generator) in buffer and then assessing the number of viable colonies. A tendency of an increased sensitivity for ∆ohr cells in relation to the wild-type strain was detected (Fig. S8D), which was statistically significant in cells, where catalase was inhibited by ATZ (Fig. 7D). In contrast, both ATZ-treated and untreated wild-type cells were equally sensitive to SIN-1, and deletion of ahpC gene did not affect the viability of bacterial cells (Fig. S8C). Furthermore, the expression of ohr was induced in cells exposed to SIN-1 (Fig. 7C), implicating PaOhr in the response of P. aeruginosa to peroxynitrite.

Discussion

Previous work has indicated that substrate hydrophobicity is a major physicochemical determinant of substrate specificity for Ohr (16, 19, 21, 22). Accordingly, docking analysis performed here with XfOhr indicated that nonpolar contacts appear to be major determinants in the binding of lipid hydroperoxides within the active site (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1A). The elongated shape of the substrate appears to be another feature to be considered presumably because the substrates, once docked, fill a Y-shaped cavity on the enzyme generating a large hydrophobic contact area, which would be anticipated to contribute significantly to the interaction energy. Indeed, cholesterol, which is highly hydrophobic but with a shape very distinct from PEG and fatty acids, did not dock well into the XfOhr active site (Fig. S1B). Other biochemical (Figs. 2 and 3) and microbiological (Fig. 6) assays also indicated that ChOOH is not an Ohr substrate. For example, in the case of the MIC assay (Fig. 6), in addition to the natural surfactants of P. aeruginosa, Brij-58 (1%) was supplemented during the experiments. Despite this fact, the ∆ohr strain was no more sensitive to ChOOH than the wild-type strain, indicating a lack of significant affinity between ChOOH and the enzyme.

The AhpE/Ohr competitive assay developed here was straightforward in comparison to other methods previously described, allowing us to obtain the second-order rate constants for the oxidation of peroxidatic Cys by distinct hydroperoxides. Importantly, we could use fatty acid hydroperoxides in the low micromolar range (1–2 μM), which is well below the CMC of long-chain fatty acid hydroperoxides (10–40 μM). With this approach (associated with the inactivation and the MIC assays), we could unambiguously establish that long-chain fatty acid hydroperoxides are more efficiently reduced by Ohr than artificial organic hydroperoxides and H2O2 (Table 1).

In addition to fatty acid hydroperoxides, peroxynitrite was reduced with very high efficiency by XfOhr (on the order of 107 M−1⋅s−1). This finding was somehow unexpected because peroxynitrite is not a hydrophobic molecule, although the reaction of peroxynitrite with thiols involves the protonated form of peroxynitrite (peroxynitrous acid) and thiolates (48). It should be noted here that reactions of peroxynitrite with thiolates are much faster than similar reactions of thiolates with organic hydroperoxides or H2O2 (48–50). Unfortunately, there is no report of the kinetics between fatty acid hydroperoxides with noncatalytic thiols, such as free Cys or the single reduced Cys residue in BSA. Nevertheless, using the reaction between t-BHP and ordinary thiolates as a reference (51), it is evident that the gain in reactivity afforded by Ohr is two to three orders of magnitude for H2O2 and peroxynitrite, but six orders of magnitude for t-BHP (Table S1).

Table S1.

Catalytic power of XfOhr toward distinct peroxides

| Peroxide | kBSA pH 7.4 | kBSA pH indep | kOHR pH 7.4 | kOHR pH indep | kOHR/kBSA pH indep |

| H2O2 | 1.14* | 5.7* | 3 × 103† | 3 × 103† | ∼5 × 102 |

| Peroxynitrite | 2.6 × 103* | 6.5 × 104* | 2 × 107† | 1 × 108† | ∼1.5 × 103 |

| t-BHP | 0.37‡ | 1.85‡ | 2 × 106§ | 2 × 106§ | ∼1.4 × 106 |

The pH independent (indep) rate constants were calculated considering that the thiolate reacts with protonated peroxide, and taking into account a pKa value of 6.8 for peroxynitrite (50), and higher than 10.0 for H2O2 and t-BHP, and also considering a pKa for the single thiol in BSA as 8.3 (51) and for the peroxidatic thiol in Ohr as 5.2 (77).

Temperature of 37 °C (49).

Temperature of 25 °C (this work).

Room temperature (51).

Temperature of 37 °C (23).

According to the Brønsted relationship, the pKa of the leaving group is a factor that is involved in the reactivity of thiolates with hydroperoxides (13). The pKa values for aliphatic alkoxyl groups, which are the leaving groups corresponding to t-BHP and fatty acid hydroperoxides, are expected to have similar values (13). Therefore, it is reasonable to think that the reactions of t-BHP and fatty acid hydroperoxides with ordinary thiols (e.g., the thiol of BSA) are within the same range and that the catalytic power of Ohr proteins for fatty acid hydroperoxides is therefore extraordinary (at least 106-fold increase). This high reactivity is probably related to its capacity to bind and orient the peroxyl group of fatty acid hydroperoxides toward the thiolate group of Cys61 (Fig. 1), decreasing the free energy of the transition state.

In the case of the reduction of peroxynitrite by Ohr, the corresponding rate constant is one of the highest determined so far (52). In fact, the rate constant of peroxynitrite reduction by Ohr is comparable to the rate constants reported for Prxs and thiol- or selenol-dependent Gpxs (10, 12, 13, 53–55). Therefore, it is feasible that Ohr plays a relevant role in vivo in the reduction of peroxynitrite. This role might be significant, especially considering that inducible nitric oxide synthase (and possibly peroxynitrite as a product of nitric oxide) displays a crucial role in the pulmonary response to P. aeruginosa infection (42, 56). Also for plant pathogens (e.g., X. fastidiosa), peroxynitrite and other nitric oxide-mediated processes are emerging as relevant players in defense responses (41). Accordingly, the levels of PaOhr are induced in cells exposed to the peroxynitrite generator (Fig. 7C), and the Δohr strain treated with ATZ is sensitive to this oxidant (Fig. 7D). However, at the moment, it is difficult to identify if the response of P. aeruginosa to SIN-1 is a direct effect of peroxynitrite or if it is due to some secondary derived oxidant. For instance, it is well known that lipids are targets for peroxynitrite oxidation and could release secondary products that might mount the adaptive response of P. aeruginosa (57). The involvement of catalase in the response of bacteria to peroxynitrite was shown previously in F. tularensis and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, two microorganisms devoid of Ohr (47, 58), although the latter does contain an osmC gene. Our data indicate that especially Ohr and possibly catalase cooperate in the protection of P. aeruginosa against this oxidant (Fig. 7).

In addition to peroxynitrite, fatty acid hydroperoxides are involved in host–pathogen interactions (59, 60). Fatty acid hydroperoxides could be generated by nonenzymatic lipid peroxidation of cis-vaccenic acid and other monounsaturated fatty acids that are present in bacterial membranes, because most bacteria synthesize little or no polyunsaturated fatty acids (61). For this reason, it is assumed that nonenzymatic lipid peroxidation is not a favorable process in bacteria. Alternatively, Ohr may reduce polyunsaturated fatty acid hydroperoxides enzymatically generated by plant or animal hosts. In mammals, pathogens, such as P. aeruginosa, can activate host cytosolic PLA2 (62), releasing arachidonic acid (20:4 ratio) for oxidative modification by enzymes, such as 5-lipoxygenase or 15-lipoxygenase (63). Products of lipoxygenases have profound and distinct effects on the outcome of inflammation (59, 64). Given that endogenous levels of fatty acid hydroperoxides, such as 5-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid [5(S)-HpETE] or 15(S)-HpETE, regulate acute inflammation (59), it is reasonable to hypothesize that Ohr might somehow impact the progression of the immune response. In plants, the immune response is also mediated by oxidized products of fatty acids, derived from linoleic (18:2 ratio) and linolenic (18:3 ratio) acids in this case (60). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that Ohr might subvert host immune pathways by some still unknown mechanisms (65). Remarkably, P. aeruginosa contains endogenous enzymatic systems capable of oxidizing unsaturated fatty acids (especially oleic acid) to hydroperoxide and hydroxide derivatives, whose biological function is still elusive (66, 67). Moreover, the experimental approach presented herein allowed dissecting the relevance of Ohr toward three different groups of biologically relevant hydroperoxides, underscoring the complementary role that different thiol- and heme-dependent peroxidases have on controlling cellular oxidative signaling and damage.

Materials and Methods

Reagents, Including Hydroperoxides.

All reagents purchased had the highest degree of purity. The t-BHP was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich Co. CHP and H2O2 were obtained Merck KGaA. XfOhr and PaOhr, as well as MtAhpE, were obtained and, in some experiments, reduced as previously described (8, 55). The 15(S)-HpETE and 5(S)-HpETE were purchased from Cayman Chemical.

Photochemical Synthesis of Lipid Hydroperoxides.

Oleic acid, linoleic acid, cholesterol, and phosphatidylcholine were photooxidized to the corresponding hydroperoxides according to the method of Miyamoto et al. (68). This procedure is based on the oxidation of lipids by singlet molecular oxygen produced in an O2-saturated atmosphere using methylene blue as a photosensitizer. OAOOHs, LAOOHs, and ChOOHs were purified by flash-column chromatography and were quantified by iodometry (68). The hydroperoxide isomers were not separated among themselves, only from the parental lipids. Phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxide was purified by HPLC and was quantified by phosphorus assay and iodometry (69).

Docking Lipid Hydroperoxides in Ohr.

Using the X. fastidiosa Ohr structure (PDB ID code 1ZB8) as a template, docking analysis was carried out using Gold software, version 5.0 (70), utilizing organic hydroperoxides with distinct chemical structures.

Lipoamide-Lipoamide Dehydrogenase Peroxidase-Coupled Assay.

The lipoyl peroxidase activity of Ohr was determined as previously described (23). Reactions were followed by decay of A340 (ε = 6,290 M−1⋅cm−1) due to NADH oxidation. In some cases, several hydrophobic hydroperoxides were solubilized in Tween-20 or Triton X-100 as described throughout the main text and appropriate controls were performed.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of the Products Formed in the Ohr Reaction with LAOOH and OAOOH.

OAOOH or LAOOH (4 μM) was incubated in the presence of an equimolar concentration of reduced XfOhr for 1 min at 37 °C in sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM), pH 7.4, containing diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) (0.1 mM). As a control reaction, OAOOH and LAOOH were incubated with previously alkylated Ohr (0.2 mM NEM). Afterward, an organic extraction was performed, and the products were analyzed by HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed in a triple-quadrupole instrument (Quattro II; Micromass) essentially as described by Miyamoto et al. (68).

Analysis of Ohr Hyperoxidation and Inactivation.

Freshly purified recombinant XfOhr (300 μM) was reduced for 1 h using DTT (100 mM). Afterward, excessive DTT was removed by gel filtration (PD-10 desalting; GE Healthcare), and the amount of protein recovered was quantified by its A280 (ε = 3,960 M−1⋅cm−1; determined by the ProtParam tool ExPASy). Next, XfOhr (10 μM) was treated with increasing amounts of hydroperoxides (as depicted in Fig. 3B and Fig. S4) for 1 h at 37 °C in sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM), pH 7.4, containing DTPA (1 mM) and 0.15% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 or 0.25% (vol/vol) Tween-20.

After these pretreatments, XfOhr was again submitted to gel filtration to remove excessive hydroperoxides, and the recovered enzyme was again quantified by A280. Finally, the same sample of XfOhr was assayed by the lipoamide-lipoamide dehydrogenase–coupled assay (using t-BHP as a substrate) and by nonreducing SDS/PAGE, which allow the assessment of the XfOhr oxidative state (22).

Digestion of Phosphatidylcholine Hydroperoxide with PLA2.

This enzymatic digestion was performed as previously described (71). In a solution containing CaCl2 (10 mM), KCl (35 mM), and Tris (20 mM) at pH 8.0, phosphatidylcholine (catalog no. P3556; Sigma) from egg yolk was added at a final concentration equal to 100 μM. The solution was stirred for 1 min abruptly. Thereafter, PLA2 (P0861 Sigma–Aldrich Co.) was added (final amount of 10 units), and the solution was then incubated for 15 min or 30 min at 40 °C under gentle agitation. After this time, the components of the dihydrolipoamide system and Triton X-100 were added for testing the activity of XfOhr on phospholipids treated with PLA2.

Kinetics of Organic Hydroperoxide Reduction by Ohr.

A competition method was developed here, taking advantage of the fact that Ohr from X. fastidiosa and P. aeruginosa does not possess Trp residues, and consequently displays low intrinsic fluorescence. In contrast, MtAhpE has intrinsic fluorescence that decreases upon oxidation (8, 55). As expected, XfOhr practically lacks intrinsic fluorescence when excited at 295 nm, in contrast to MtAhpE (Fig. S5). Therefore, the assay developed here is based on the competition between Ohr and MtAhpE for distinct hydroperoxides, monitoring the intrinsic fluorescence of MtAhpE when exciting at 295 nm, either following the time course of the reaction (using an SX20 Applied Photophysics stopped-flow apparatus) or at final time points (using an Aminco Bowman Series 2 luminescence spectrophotometer or a Cary Eclipse Fluorimeter). Rate constants for MtAhpE oxidation were determined for those organic hydroperoxides that were not previously studied by Reyes et al. (8) and Hugo et al. (55).

Concentrations of MtAhpE, Ohr, and hydroperoxide used were typically 2 μM, 2–8 μM, and 1.8 μM, respectively. Because enzyme concentration decreased during the time course of the experiment, no pseudo–first-order conditions applied. Therefore, we used the following equation (Eq. 1) to find out the relationship between the rate constants for the reaction of a selected hydroperoxide with Ohr (kOHR) and with MtAhpE (kAhpE):

| [1] |

where kC. Prot is the rate constant for the reaction between a selected hydroperoxide with the protein competing with Ohr for it (in this case, reduced MtAhpE, whose reactivity with the hydroperoxide is either already known or determined herein, as described in Fig. S6); kOHR is the rate constant of the reaction between the hydroperoxide with reduced Ohr; [redC. Prot]0 is the initial concentration of the reduced competing protein; [oxC. Prot]∞ corresponds to the final concentration of the competing protein in the oxidized state; [redOhr]0 is the initial concentration of reduced Ohr; and [oxOhr]∞ is the final concentration of oxidized Ohr, determined as [oxC. Prot]∞ formed in the absence minus the presence of Ohr (50). The final concentration of MtAhpE in the oxidized state was determined assuming an equimolar reaction with hydroperoxide in the absence of the competing protein.

Kinetics of Peroxynitrite Reduction by Ohr.

The reduction of peroxynitrite by XfOhr was investigated using different methodologies. First, the initial rate of peroxynitrite decomposition was followed at 310 nm due to its intrinsic absorbance in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of reduced XfOhr in 100 mM (pH 7.4) sodium phosphate buffer containing DTPA (0.1 mM) at 25 °C, using an SX20 Applied Photophysics stopped-flow apparatus (50). In a second approach, the kinetics of peroxynitrite reduction were indirectly determined using a competition assay between reduced XfOhr and HRP for peroxynitrite (10, 11, 50). HRP compound I formation was measured at various concentrations of reduced XfOhr, and experimental curves were fitted to exponential curves before the slow decay of compounds I –II occurred. Because no pseudo–first-order conditions applied (reduced XfOhr concentration decreased during the time course of the experiment), we used Eq. 1 to find out the relationship between the kHRP (the C. Prot in this assay) and kOHR.

The final concentration of compound I was quantitated using the reported ε398 nm = 42,000 M−1⋅cm−1 and the final concentration of oxidized XfOhr, determined as compound I formed in the absence minus the presence of XfOhr (11). To perform these calculations, we previously determined the rate constant between HRP and peroxynitrite as 2.2 × 106 M−1⋅s−1 at pH 7.4 and 25 °C for the specific batch and experimental conditions used in the experiments described here. Indeed, the rate constant changed from batch to batch of HRP (72).

Finally, the competition approach between reduced Ohr and MtAhpE described above was also used for determining the kinetics of peroxynitrite-mediated MtAhpE oxidation.

Strains and Growth Conditions.

P. aeruginosa UCBPP-PA14 (73) wild-type and MAR2xT7 mutants (74) (see Table S2), and E. coli strains were grown in lysogenic broth (LB) medium at 37 °C supplemented, when necessary, with gentamicin (10 μg/mL), carbenicillin (300 μg/mL), or ampicillin (100 μg/mL).

Table S2.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strains/plasmids | Characteristics | Source |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PA14 | Clinical isolate UCBPP-PA14 | (73) |

| Δohr | PA14 MAR2xT7::PA14_27220 | (74) |

| ΔahpC1 | PA14 MAR2xT7::PA14_01710 | (74) |

| ΔahpC2 | PA14 MAR2xT7::PA14_18690 | (74) |

| Δtpx | PA14 MAR2xT7::PA14_31810 | (74) |

| Δgpx | PA14 MAR2xT7::PA14_27520 | (74) |

| LN01 | PA14 pUCp18_empty | This study |

| LN02 | Δohr pUCp18_empty | This study |

| LN03 | PA14 pUCp18_pohr | This study |

| LN04 | Δohr pUCp18_pohr | This study |

| LN05 | Δohr pUCp18_ ahpC1_HA | This study |

| LN06 | Δohr pUCp18_ ahpC2_HA | This study |

| LN07 | Δohr pUCp18_tpx_HA | This study |

| LN08 | Δohr pUCp18_gpx_HA | This study |

| LN09 | ΔahpC1 pUCp18_empty | This study |

| LN10 | Δtpx pUCp18_empty | This study |

| LN11 | Δgpx pUCp18_empty | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUCp18 | Stable expression vector used in Pseudomonas spp., Apr | (78) |

| pGEM T easy | TA cloning vector, Apr | Promega |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; HA, hemagglutinin.

Cloning for Complementation Assays in P. aeruginosa.

The coding region from ohr gene (PA14_27220) with its 150-bp upstream sequence and ahpC (PA14_01710), ahpC2 (PA14_18690), tpx (PA14_31810), and gpx (PA14_27520) genes (corresponding to fragments of 780 bp, 561 bp, 600 bp, 485 bp, and 490 bp, respectively) were amplified using oligonucleotides described in Table S3). With the exception of ohr, all genes were cloned without a stop codon and harboring a human influenza hemagglutinin (HA) tag inserted at 3′, allowing us to check their expression levels in P. aeruginosa cells by Western blotting.

Table S3.

Oligos used in this work

| Oligos | Sequence |

| Paohr_F_EcoRI | CGCGAATCCGGCGAAGGTCTGATTACCCGC |

| Paohr_R_BamHI | CGCGGATCCTCAGACCGACACGTTCAGGCG |

| PA14_01710_ahpC1_Pa_F | AGCTGAATTCATGTCCCTGATCAACACTCAAG |

| PA14_01710_ahpC1_Pa_R | AGCTAAGCTTAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAGATCTTGCCGACCAGGTCCA |

| PA14_18690_ahpC2_F | AGCTGGTACCATGAGCGTACTCGTAGGTAA |

| PA14_18690_ahpC2_R | AGCTAAGCTTAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTACAGCTTGCTGGCGTTCTC |

| PA14_31810_tpx_F | AGCTGAATTCATGGCTCAAGTGACTCTCAAGG |

| PA14_31810_tpx_R | AGCTAAGCTTAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAGAGAGCCGCCAGGGCCGCC |

| PA14_27520_gpx_F | AGCTGAATTCACAAGCCATGAGCGATTCTC |

| PA14_27520_gpx_R | AGCTAAGCTTAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTATTCAAGCAGCGCCTCGAT |

Underlined letters indicate a restriction site, and bold letters indicate HA tag sequence. F, forward; R, reverse.

The final products were cloned into EcoRI and BamHI sites of the broad-host range vector pUCp18 (GenBank accession no. U07164) previously digested with the same enzymes. The pUCp18 constructs were introduced into P. aeruginosa PA14 wild-type and MAR2xT7 transposon ohr mutant (∆ohr) cells by electroporation (75). As a control, the same strains were transformed with empty pUCp18 vector. All PCR reactions were carried out with Thermo Scientific High Fidelity Taq Polymerase using genomic DNA of PA14 as a template. Errors from PCR reactions were checked by sequencing the clones.

MIC Assay.

Cultures of P. aeruginosa (PA14 and ∆ohr) were grown on LB medium at 37 °C until OD600 = 1. After that time, cultures were diluted in fresh LB medium supplemented with an appropriate antibiotic to OD600 = 0.01; then, 150 μL was dispensed in 96-well plates previously loaded with different concentrations of tested hydroperoxides. Afterward, assay plates were incubated at 37 °C under agitation (200 rpm), and the results were recorded after 16 h. To increase the solubility of ChOOH, LB medium was supplemented with 1% Brij-58. Concentrations of hydroperoxides and conditions of solubilization are described in Figs. 6 and 7 and Fig. S7.

Colony Counting Assay to Assess SIN-1 Sensitivity.

Cultures of P. aeruginosa were grown on LB medium at 37 °C until OD600 = 1. After that point, cultures were washed twice in Dulbecco PBS (Life Technologies) and diluted to OD600 = 0.01 in the same buffer. A volume of 200 μL of the cell suspension was incubated with 5 mM catalase inhibitor ATZ for 10 min at room temperature without agitation. After that time, 6.2 μL of 96 mM SIN-1 solution (diluted in DMSO) was added at the bottom of the tube and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C at 200 rpm, and treated cultures were then serially diluted in 10 mM MgSO4 and plated on solid LB medium to count the number of viable cells by colony formation unit. As a control, the same treatment was carried out only with DMSO. The results were expressed by the relative percentage, compared with controls, of viable cells remaining after treatment. The statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test (P < 0.05).

Ohr Expression upon Oxidative Insults.

Cultures of P. aeruginosa (PA14, ∆ohr, and ∆ohrR) were grown on M9 medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose at 37 °C and 200 rpm until OD600 = 0.5. After that time, 500 μL of each culture was separated in different flasks to receive the treatments (200 µM t-BHP, 50 μM LAOOH, and 1 mM SIN-1). As a control, the same volumes of the solvents in which the previous compounds were diluted [water, 5% (vol/vol) methanol, and 5% (vol/vol) DMSO, respectively] were added. After 30 min of treatment (37 °C, 200 rpm), cells were pelleted and then resuspended in Laemmli buffer and processed for SDS/PAGE analysis. The gel was electroblotted onto a 0.45-μm nitrocellulose membrane in Tris⋅glycine buffer at 24 V/600 mA for 30 min. Blotted membranes were blocked for 3 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) and 5% (vol/wt) nonfat dry milk (Bio-Rad). The membrane was then incubated with a rabbit anti-XfOhr polyclonal serum (1:1,000 in TBS-T) overnight at 4 °C, followed by washing with TBS-T. The membrane was subsequently incubated with an anti-rabbit IgG-alkaline phosphatase antibody (KPL, Inc.; 1:1,000 in TBS-T) for 2 h. After washing, the proteins were detected following incubation with alkaline phosphatase substrates: 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (0.3 mg/mL)/nitro blue tetrazolium (0.1 mg/mL) on an appropriate buffer [10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 9.0), 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2].

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Regina Baldini [Instituto Quimica, Universidade de São Paulo (USP)] and Laurence G. Rahme (Harvard University) for providing PA14 and strains from a transposon library. We also thank Adriano de Britto Chaves-Filho (Instituto Quimica, USP) for his support in mass spectrometry analysis. This work was financially supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) Grant 13/07937-8 (Redox Processes in Biomedicine) (to M.A.d.O., S.M., P.D.M., O.A., and L.E.S.N.), NIH Grant 1R01AI095173 (to R.R.), a grant from the Universidad de la República (Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica, Uruguay; to R.R.), and a grant from Ridaline (Fundación Manuel Pérez) (to R.R.). M.H. was the recipient of a fellowship from the Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación (Uruguay), and T.G.P.A. (2008/07971-3) and D.A.M. (2012/21722-1) were recipients of fellowships from FAPESP.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1619659114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Flohé L. The impact of thiol peroxidases on redox regulation. Free Radic Res. 2016;50(2):126–142. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2015.1046858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhee SG, Woo HA, Kil IS, Bae SH. Peroxiredoxin functions as a peroxidase and a regulator and sensor of local peroxides. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(7):4403–4410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.283432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winterbourn CC, Hampton MB. Thiol chemistry and specificity in redox signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(5):549–561. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peskin AV, et al. The high reactivity of peroxiredoxin 2 with H2O2 is not reflected in its reaction with other oxidants and thiol reagents. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(16):11885–11892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall A, Parsonage D, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Structural evidence that peroxiredoxin catalytic power is based on transition-state stabilization. J Mol Biol. 2010;402(1):194–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portillo-Ledesma S, et al. Deconstructing the catalytic efficiency of peroxiredoxin-5 peroxidatic cysteine. Biochemistry. 2014;53(38):6113–6125. doi: 10.1021/bi500389m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeida A, et al. The extraordinary catalytic ability of peroxiredoxins: A combined experimental and QM/MM study on the fast thiol oxidation step. Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50(70):10070–10073. doi: 10.1039/c4cc02899f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reyes AM, et al. Oxidizing substrate specificity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis alkyl hydroperoxide reductase E: Kinetics and mechanisms of oxidation and overoxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51(2):464–473. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manta B, et al. The peroxidase and peroxynitrite reductase activity of human erythrocyte peroxiredoxin 2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;484(2):146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogusucu R, Rettori D, Munhoz DC, Netto LE, Augusto O. Reactions of yeast thioredoxin peroxidases I and II with hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite: Rate constants by competitive kinetics. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42(3):326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toledo JC, Jr, et al. Horseradish peroxidase compound I as a tool to investigate reactive protein-cysteine residues: From quantification to kinetics. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50(9):1032–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubuisson M, et al. Human peroxiredoxin 5 is a peroxynitrite reductase. FEBS Lett. 2004;571(1-3):161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trujillo M, et al. Pre-steady state kinetic characterization of human peroxiredoxin 5: Taking advantage of Trp84 fluorescence increase upon oxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;467(1):95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mongkolsuk S, Praituan W, Loprasert S, Fuangthong M, Chamnongpol S. Identification and characterization of a new organic hydroperoxide resistance (ohr) gene with a novel pattern of oxidative stress regulation from Xanthomonas campestris pv. phaseoli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(10):2636–2643. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.10.2636-2643.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atichartpongkul S, et al. Bacterial Ohr and OsmC paralogues define two protein families with distinct functions and patterns of expression. Microbiology. 2001;147(Pt 7):1775–1782. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-7-1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cussiol JR, Alves SV, de Oliveira MA, Netto LE. Organic hydroperoxide resistance gene encodes a thiol-dependent peroxidase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(13):11570–11578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lesniak J, Barton WA, Nikolov DB. Structural and functional characterization of the Pseudomonas hydroperoxide resistance protein Ohr. EMBO J. 2002;21(24):6649–6659. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez C, Barondess J, Manoil C, Beckwith J. The use of transposon TnphoA to detect genes for cell envelope proteins subject to a common regulatory stimulus. Analysis of osmotically regulated genes in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1987;195(2):289–297. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90650-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lesniak J, Barton WA, Nikolov DB. Structural and functional features of the Escherichia coli hydroperoxide resistance protein OsmC. Protein Sci. 2003;12(12):2838–2843. doi: 10.1110/ps.03375603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin DH, et al. Structure of OsmC from Escherichia coli: A salt-shock-induced protein. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 5):903–911. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904005013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meunier-Jamin C, Kapp U, Leonard GA, McSweeney S. The structure of the organic hydroperoxide resistance protein from Deinococcus radiodurans. Do conformational changes facilitate recycling of the redox disulfide? J Biol Chem. 2004;279(24):25830–25837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira MA, et al. Structural insights into enzyme-substrate interaction and characterization of enzymatic intermediates of organic hydroperoxide resistance protein from Xylella fastidiosa. J Mol Biol. 2006;359(2):433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cussiol JR, Alegria TG, Szweda LI, Netto LE. Ohr (organic hydroperoxide resistance protein) possesses a previously undescribed activity, lipoyl-dependent peroxidase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(29):21943–21950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.117283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ta P, Buchmeier N, Newton GL, Rawat M, Fahey RC. Organic hydroperoxide resistance protein and ergothioneine compensate for loss of mycothiol in Mycobacterium smegmatis mutants. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(8):1981–1990. doi: 10.1128/JB.01402-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klomsiri C, Panmanee W, Dharmsthiti S, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. Novel roles of ohrR-ohr in Xanthomonas sensing, metabolism, and physiological adaptive response to lipid hydroperoxide. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(9):3277–3281. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.3277-3281.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chuchue T, et al. ohrR and ohr are the primary sensor/regulator and protective genes against organic hydroperoxide stress in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(3):842–851. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.842-851.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh SY, Shin JH, Roe JH. Dual role of OhrR as a repressor and an activator in response to organic hydroperoxides in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(17):6284–6292. doi: 10.1128/JB.00632-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roveri A, Maiorino M, Nisii C, Ursini F. Purification and characterization of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase from rat testis mitochondrial membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1208(2):211–221. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas JP, Geiger PG, Maiorino M, Ursini F, Girotti AW. Enzymatic reduction of phospholipid and cholesterol hydroperoxides in artificial bilayers and lipoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1045(3):252–260. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90128-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pal S, Moulik SP. Cholesterol solubility in mixed micellar solutions of ionic and non-ionic surfactants. J Lipid Res. 1983;24(10):1281–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rand Doyen J, Yucer N, Lichtenberger LM, Kulmacz RJ. Phospholipid actions on PGHS-1 and -2 cyclooxygenase kinetics. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2008;85(3-4):134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richieri GV, Ogata RT, Kleinfeld AM. A fluorescently labeled intestinal fatty acid binding protein. Interactions with fatty acids and its use in monitoring free fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(33):23495–23501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sermon BA, Eccleston JF, Skinner RH, Lowe PN. Mechanism of inhibition by arachidonic acid of the catalytic activity of Ras GTPase-activating proteins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(3):1566–1572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serth J, Lautwein A, Frech M, Wittinghofer A, Pingoud A. The inhibition of the GTPase activating protein-Ha-ras interaction by acidic lipids is due to physical association of the C-terminal domain of the GTPase activating protein with micellar structures. EMBO J. 1991;10(6):1325–1330. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miki T, Orii Y. The reaction of horseradish peroxidase with hydroperoxides derived from Triton X-100. Anal Biochem. 1985;146(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haberland ME, Reynolds JA. Self-association of cholesterol in aqueous solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70(8):2313–2316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.8.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baker LM, Poole LB. Catalytic mechanism of thiol peroxidase from Escherichia coli. Sulfenic acid formation and overoxidation of essential CYS61. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(11):9203–9211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209888200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson KJ, Parsonage D, Karplus PA, Poole LB. Evaluating peroxiredoxin sensitivity toward inactivation by peroxide substrates. Methods Enzymol. 2013;527:21–40. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405882-8.00002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsonage D, Karplus PA, Poole LB. Substrate specificity and redox potential of AhpC, a bacterial peroxiredoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(24):8209–8214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708308105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alvarez MN, Peluffo G, Piacenza L, Radi R. Intraphagosomal peroxynitrite as a macrophage-derived cytotoxin against internalized Trypanosoma cruzi: consequences for oxidative killing and role of microbial peroxiredoxins in infectivity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(8):6627–6640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]