Significance

Reproduction in placental mammals relies on potent control of the mother’s immune system to not attack the developing fetus. As a bystander effect, pregnancy also potently suppresses the activity of the autoimmune disease multiple sclerosis (MS). Here, we report that T cells are able to directly sense progesterone via their glucocorticoid receptor (GR), resulting in an enrichment of regulatory T cells (Tregs). By using an MS animal model, we found that the presence of the GR in T cells is essential to increase Tregs and confer the protective effect of pregnancy, but not for maintaining the pregnancy itself. Better understanding of this tolerogenic pathway might yield more specific therapeutic means to steer the immunological balance in transplantation, cancer, and autoimmunity.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, autoimmunity, pregnancy, Treg, steroid hormones

Abstract

Pregnancy is one of the strongest inducers of immunological tolerance. Disease activity of many autoimmune diseases including multiple sclerosis (MS) is temporarily suppressed by pregnancy, but little is known about the underlying molecular mechanisms. Here, we investigated the endocrine regulation of conventional and regulatory T cells (Tregs) during reproduction. In vitro, we found the pregnancy hormone progesterone to robustly increase Treg frequencies via promiscuous binding to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in T cells. In vivo, T-cell–specific GR deletion in pregnant animals undergoing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the animal model of MS, resulted in a reduced Treg increase and a selective loss of pregnancy-induced protection, whereas reproductive success was unaffected. Our data imply that steroid hormones can shift the immunological balance in favor of Tregs via differential engagement of the GR in T cells. This newly defined mechanism confers protection from autoimmunity during pregnancy and represents a potential target for future therapy.

Reproduction is fundamental to the maintenance and evolution of species. To ensure successful pregnancy, mothers have to establish robust immunological tolerance toward the semiallogeneic conceptus providing a secure niche for fetal development. Multiple mechanisms have evolved to prevent fetus-directed immune responses and alloreactive infiltration of the fetomaternal interface (1). These include creating a privileged local microenvironment that hampers T-cell priming and infiltration (2–4) but also imply global modulation of the immune system by pregnancy hormones and the shedding of fetal antigen into the mothers circulation (5).

Intriguingly, pregnancy is also well known to suppress the inflammatory activity of a number of cell-mediated autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (6, 7), autoimmune hepatitis (8), and multiple sclerosis (MS) (9, 10). However, this beneficial effect is limited to the period of gestation and usually followed by a rebound of disease activity postpartum. In the case of MS, third trimester pregnancy leads to a remarkable reduction of the MS relapse rate (11), which exceeds the effects of most currently available disease-modifying drugs. Similarly, pregnancy as well as treatment with pregnancy hormones protect rodents from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a widely used animal model of MS (12) in both SJL/J and C57BL/6 mice (13–16), underpinning an interaction between pregnancy-related immune and endocrine adaptations and central nervous system (CNS) autoimmunity (17).

The sensitive balance between conventional effector T cells (Tcons) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) has transpired as a common theme that connects reproductive biology and autoimmunity on a mechanistic level (18–21). Tregs are characterized by the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) and effectively control effector responses mounted by Tcons in response to antigen-specific activation. In the context of pregnancy, Tregs were shown to expand to safeguard against fetal rejection by establishing antigen-directed immunological tolerance (18, 22). Depletion of Tregs results in fetal loss (23). Pregnancy-related hormonal signals, including estrogens and progesterone (1, 24, 25), appear to support Treg proportion and function, although their exact mode of action remains incompletely understood.

In the context of autoimmunity, Tregs are essential in suppressing autoreactive responses. Foxp3 deficiency results in generalized autoimmune inflammation evident in scurfy mice (2–4, 26) and in patients suffering from immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked syndrome (IPEX) (5, 27). Beyond that, quantitative or functional Treg impairment has been described in a number of autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (6, 7, 28, 29), rheumatoid arthritis (8, 30, 31), and type I diabetes (9, 10, 32). In MS, Tregs were reported to possess diminished suppressive potential (11, 33, 34) and decreased expression of Foxp3 and immunosuppressive cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) (12, 35–37).

However, it is still unknown which pregnancy-related changes account for the enhanced control of autoreactive responses. Here, we sought to unravel the molecular mechanisms that confer the beneficial effect of pregnancy on autoimmunity. By studying the impact of pregnancy and pregnancy hormones on T-cell subsets including Tregs, we provide evidence that differential sensitivity to glucocorticoid receptor (GR) activity is a hitherto unrecognized mechanism shaping the T-cell compartment. By targeted GR deletion in T cells, we show a selective disruption of pregnancy-induced protection from autoimmunity.

Results

Treg Dynamics During Pregnancy.

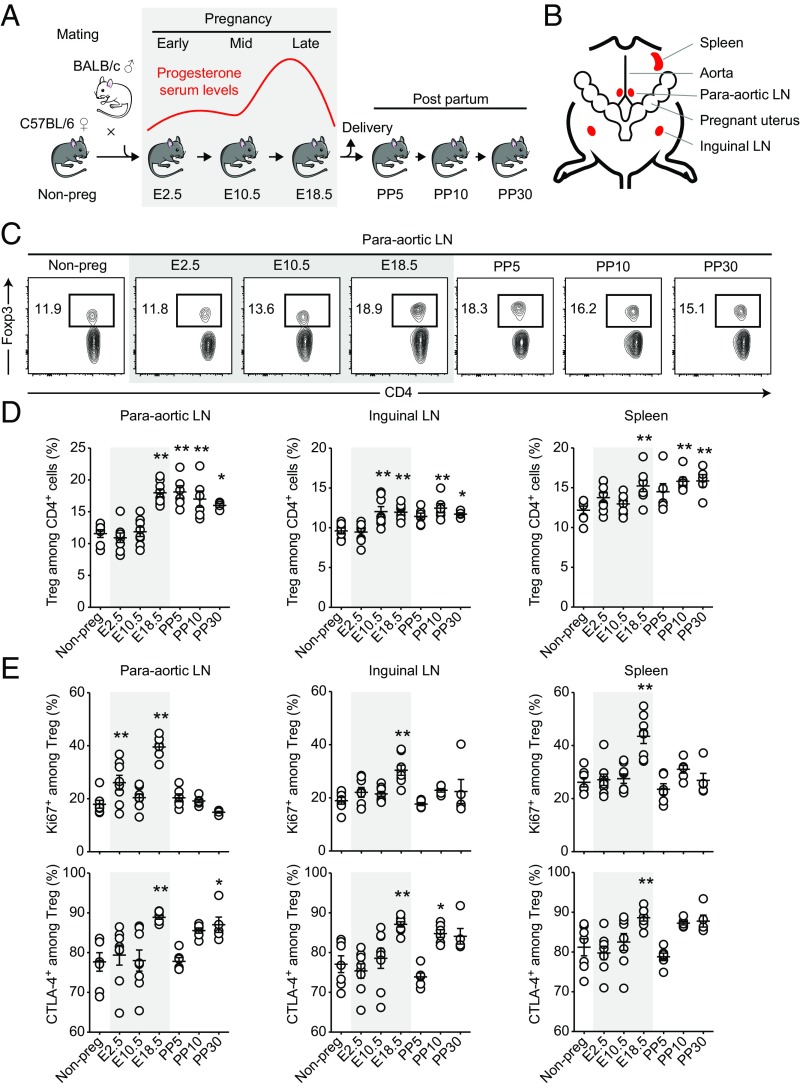

We first characterized the relative abundance and phenotype of Tcons and Tregs throughout pregnancy and postpartum time points (Fig. 1A). Because the presence of fetuses that genetically differ from the mother is a prerequisite of robust induction of immune tolerance (13–15, 18), we performed allogeneic matings of C57BL/6 females with BALB/c males. We analyzed cells from paraaortic lymph nodes (LNs), inguinal lymph nodes, and spleen to get insight into local, regional, and systemic changes, respectively (Fig. 1B). The acquired data indicated that Treg expansion was most pronounced in the paraaortic lymph nodes that drain the fetomaternal interface. Frequencies of CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs started to increase from middle to late pregnancy (embryonic days, E10.5–E18.5) and stayed at elevated levels as long as postpartum day 30 (PP30) (Fig. 1 C and D). We observed two proliferative bursts of Tregs in early (E2.5) and late (E18.5) pregnancy by Ki67 staining, coinciding with the first contact to paternal sperm antigen and the systemic challenge with fetal antigen following placental perfusion, respectively. In line with this observation, the first expansion was limited to the local paraaortic lymph nodes, whereas the second was also detectable in regional inguinal lymph nodes and systemically in the spleen (Fig. 1E). Additionally, late pregnancy Tregs consistently showed increased expression of the immunosuppressive molecule CTLA-4 in all assessed organs, rendering them potentially more effective in controlling effector responses (Fig. 1E). CD4+Foxp3− conventional T cells (Tcons) showed only one proliferative burst in early pregnancy (E2.5) that was accompanied by increased CTLA-4 expression, whereas their proliferative activity appeared to be tightly controlled at later time points (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Treg dynamics during pregnancy. Flow cytometry analysis of paraaortic LNs, inguinal LNs, and spleen at indicated pregnancy (E2.5–E18.5) and postpartum (PP5–PP30) time points. Gray shaded areas represent pregnancy. (A) Time course of allogeneic mating, sample collection, and progesterone serum levels. (B) Overview of harvested lymphoid tissue in relation to pregnant uterus. (C) Representative dot plots of Treg frequency in paraaortic LNs. (D) Quantification of Treg frequency in indicated tissues. Each dot represents the result from one individual mouse (n = 7, 8, 8, 8, 6, 6, and 4 per time point). (E) Phenotypic characterization of Tregs. Data are pooled from multiple experimental days. Statistical analyses in D and E were performed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test in comparison with nonpregnant control mice. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

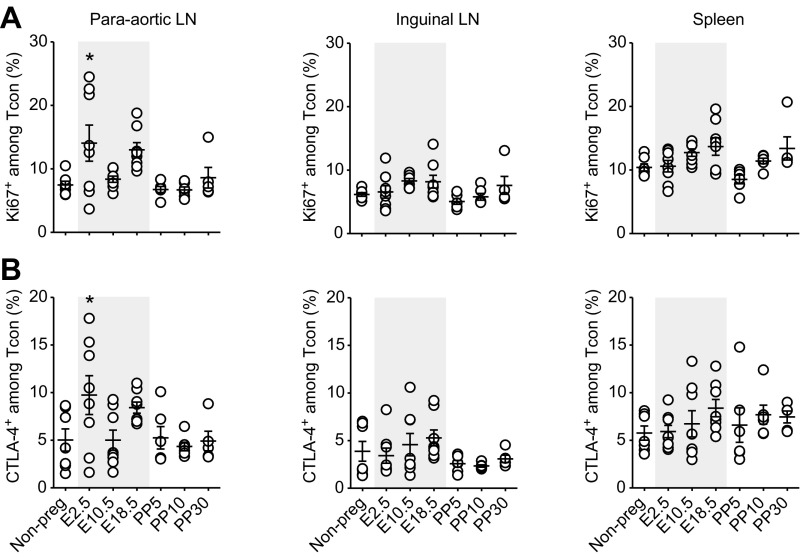

Fig. S1.

Tcon phenotype throughout pregnancy. Flow cytometry analysis of paraaortic LNs, inguinal LNs, and spleen at indicated pregnancy (E2.5–E18.5) and postpartum (PP5–PP30) time points (n = 4–8 animals per time point). Gray shaded areas represent pregnancy. Phenotypic characterization of Tcons by intracellular staining for Ki67 (A) and CTLA-4 (B). Data are pooled from multiple experimental days. Statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test in comparison with virgin control mice. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Together, the Treg response commenced in early gestation with a local proliferative burst and generalized toward systemic compartments in late gestation. Late gestational Tregs showed increased expression of CTLA-4, potentially supporting their suppressive function.

T-Cell Intrinsic Sensing of Progesterone Mediates Treg Enrichment in Vitro.

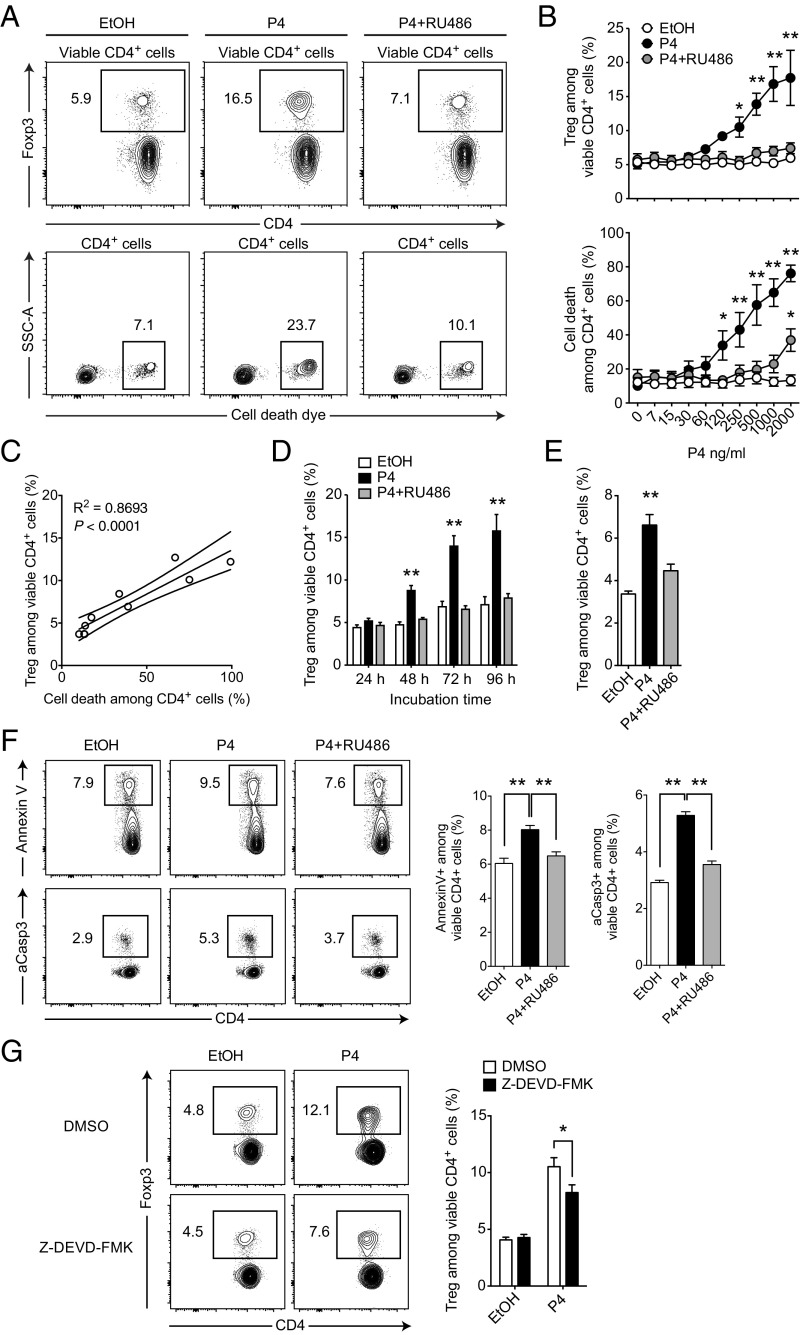

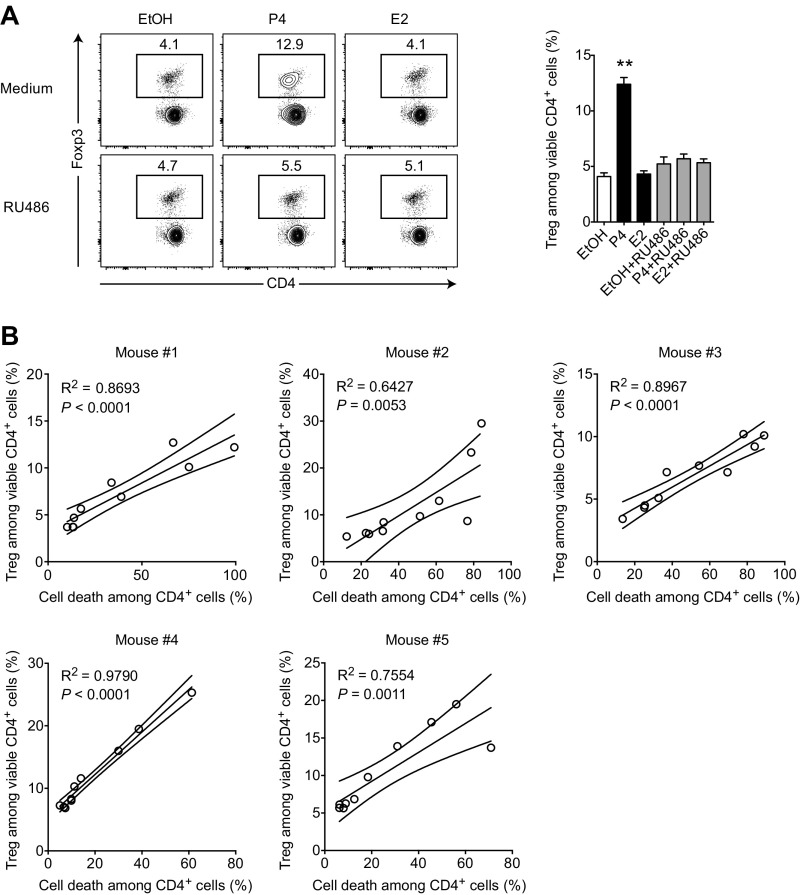

Progesterone is an essential steroid hormone for successful pregnancy outcome that peaks at late gestation (18–21, 38, 39), shortly before we observed a substantial Treg expansion (Fig. 1A). Additionally, progesterone has been shown to have beneficial effects in EAE (18, 22, 40) and to expand Treg frequencies upon in vivo treatment (24). Therefore, we tested the ability of progesterone to influence the ratio of Tregs and Tcons in splenocyte cultures. Indeed, treatment with progesterone at doses close to late gestational serum levels (∼90 ng⋅mL–1) readily increased the frequency of Foxp3+ Tregs among live CD4+ T cells from ∼5% in vehicle-treated cultures to ∼15% after 48 h (Fig. 2 A and B). We could inhibit this effect by the steroid hormone receptor antagonist mifepristone (RU486), suggesting a defined receptor-mediated rather than a pleiotropic effect. Importantly, RU486 alone as well as the pregnancy hormone estradiol had no effect on Treg frequencies (Fig. S2A). At the same time, we observed increased cell death in progesterone-treated cultures paralleling the enrichment of Tregs in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2 A–C and Fig. S2B). Prolonged cultivation amplified the effect (Fig. 2D), whereas 1 µg⋅ml–1 RU486 was under most conditions sufficient for a complete blockade (Fig. 2B). Because splenocyte cultures contain different immune cell types that could in principle be involved in sensing progesterone and mediating this finding, we sought to define the target cells of progesterone. To get a first impression, we repeated the assay with purified CD4+ T cells. Because the progesterone-induced enrichment of Treg cells was preserved in these experiments (P = 0.0003, Fig. 2E), we concluded a direct action of progesterone on CD4+ T cells.

Fig. 2.

T-cell–intrinsic sensing of progesterone mediates Treg enrichment in vitro. (A) Splenocytes were cultured for 48 h in the presence of 300 ng⋅mL–1 progesterone (P4), 1 µg⋅mL–1 mifepristone (RU486), vehicle control ethanol (EtOH), or indicated combinations. Cultures were analyzed for Treg frequency and cell death by flow cytometry. (B) Dose titration of splenocytes cultured and analyzed as described in A. (C) Correlation of Treg frequency and cell death among CD4+ cells from dose titration experiment in B. (D) Time course of splenocytes cultured and analyzed as described in A. (E) Purified CD4+ cells were cultured (0.2 × 106 cells per well) and analyzed as described in A. (F) Splenocytes were cultured as in A but analyzed after 6 h for apoptosis markers Annexin V and aCasp3. (G) Splenocytes were cultured in the presence of caspase 3 inhibitor Z-DEVD-FMK or vehicle control (DMSO) and analyzed as in A. Dot plots in A are representative of at least three independently analyzed animals. Data in B are pooled from five independent experiments with one mouse per experiment (total n = 5). Data in C show one representative animal out of five (all animals are shown Fig. S2B). Data in D show results of one experiment (n = 5). Data in E show one representative experiment out of two (each n = 4). Data in F are pooled from two independent experiments (total n = 8). Data in G are pooled from three independent experiments (total n = 10). Statistical analysis was performed by linear regression in A, two-way ANOVA in B, D, and G, and one-way ANOVA in E and F, all with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Fig. S2.

Estradiol and mifepristone fail to enrich Tregs in vitro. Treg enrichment correlates with cell death induction in CD4+ cells. (A) Splenocytes were cultured for 48 h in the presence of 300 ng⋅mL–1 progesterone (P4), 300 ng⋅mL–1 estradiol (E2), 1 µg⋅mL–1 mifepristone (RU486), vehicle control ethanol (EtOH), or indicated combinations. Cultures were analyzed for Treg frequency and cell death by flow cytometry. Progesterone serves as a positive control. Data are representative of one experiment (n = 3). (B) Correlation of Treg frequency and cell death among CD4+ cells from dose titration experiment shown in Fig. 2B. Progesterone doses are in the range of 0–2 µg⋅mL–1. Five individual mice are shown. Statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test in A and linear regression in B. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Because cell death was increased in progesterone-treated cultures, we further analyzed Annexin V and activated caspase 3 (aCasp3) to test whether CD4+ T cells were specifically driven into apoptosis. Indeed, both markers showed an increase in apoptosis after progesterone treatment, which was abolished in the presence of RU486 (Fig. 2F). More importantly, treatment with the caspase 3 inhibitor Z-DEVD-FMK reduced Treg frequencies in progesterone-treated cultures (Fig. 2G), indicating that apoptosis was directly driving Treg enrichment.

Thus, T-cell–intrinsic sensing of progesterone via a RU486-blockable receptor resulted in a shift of the immunological balance in favor of Tregs. This effect was driven by the induction of apoptosis and consecutive cell death in the CD4+ T-cell compartment.

Progesterone Acts via Promiscuous Binding to the Glucocorticoid Receptor.

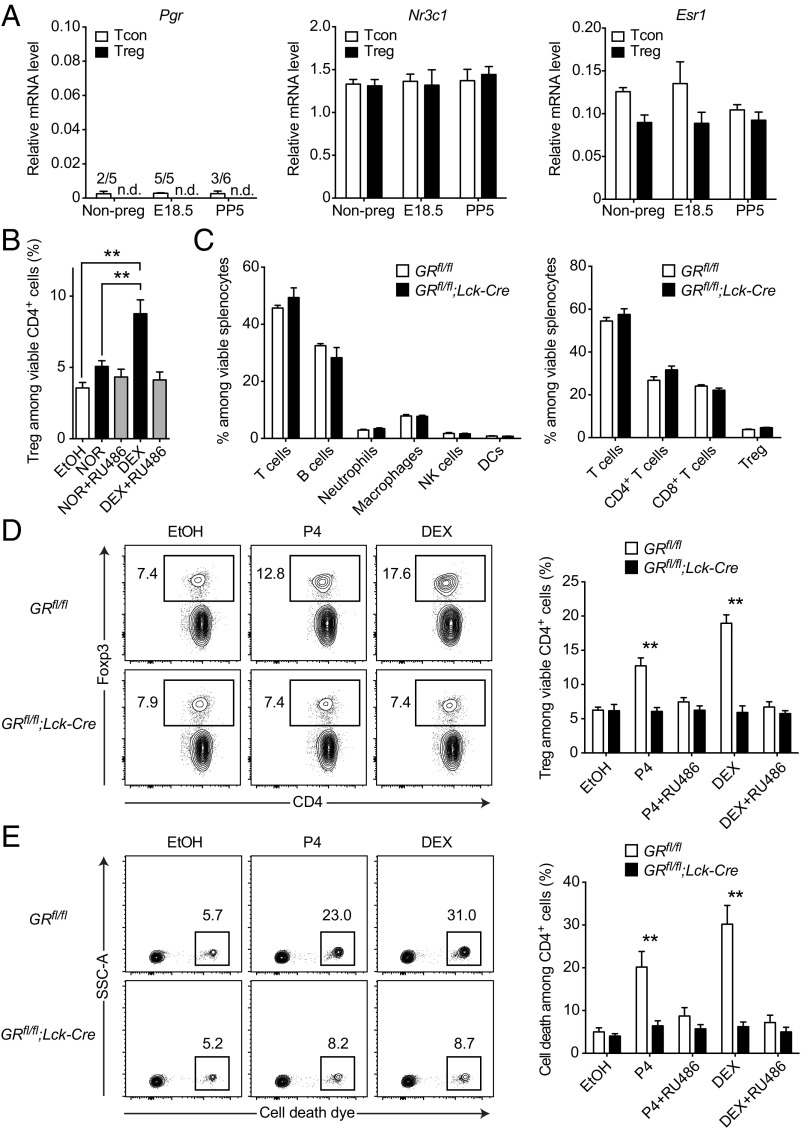

Our data suggested the existence of a RU486-blockable receptor in T cells that is engaged by progesterone and induces an enrichment of Tregs in vitro. To explore potential molecular targets of progesterone, we next performed gene expression analyses of different steroid receptors in isolated Tregs and Tcons throughout pregnancy, including the progesterone receptor (PR encoded by Nr3c3/Pgr), the glucocorticoid receptor (GR encoded by Nr3c1) and the estrogen receptor α (ER encoded by Nr3a1/Esr1). Notably, Pgr mRNA was practically absent in all conditions, whereas Nr3c1 and Esr1 mRNA could be reliably detected (Fig. 3A). Because steroid hormones are known to possess promiscuous binding activity to other steroid receptors (41), we reasoned that progesterone might signal via the GR as an alternative receptor. To test this hypothesis, we challenged splenocytes with either norgestrel (NOR) or dexamethasone (DEX), possessing high affinity to the PR or GR, respectively. Although applied at lower concentrations, DEX treatment showed a much stronger enrichment of Tregs than NOR treatment (P = 0.0009, Fig. 3A), supporting our hypothesis.

Fig. 3.

Progesterone acts via promiscuous binding to the glucocorticoid receptor. (A) Relative mRNA levels of progesterone receptor (Pgr), glucocorticoid receptor (Nr3c1), and estrogen receptor α (Esr1) in Tcons and Tregs from nonpregnant (n = 5), pregnant (E18.5; n = 5), and postpartum (PP5; n = 6) mice. mRNA was quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to Tbp. (B) Splenocytes were cultured for 48 h in the presence of 300 ng⋅mL–1 NOR, 500 pg⋅mL–1 (∼10−9 M) DEX, 1 µg⋅mL–1 mifepristone (RU486), vehicle control ethanol (EtOH), or indicated combinations. Cultures were analyzed for Treg frequency by flow cytometry. (C) Immune cell composition of splenocytes from T-cell–specific glucocorticoid receptor knockout mice (GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre) and controls (GRfl/fl) was analyzed by flow cytometry. (D and E) Splenocytes of GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre and GRfl/fl mice were cultured for 48 h in the presence of 300 ng⋅mL–1 progesterone (P4), 500 pg⋅mL–1 (∼10−9 M) DEX, 1 µg⋅mL–1 mifepristone (RU486), vehicle control ethanol (EtOH), or indicated combinations. Cultures were analyzed for Treg frequency (D) and cell death (E). Data in A are pooled from multiple experimental days. Data in B show results for one experiment (n = 4). Data in C–E show one representative experiment out of two (n = 4 per group). Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA in A and C–E and one-way ANOVA in B, all with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n.d. = not detected; x/y = number of samples with signal.

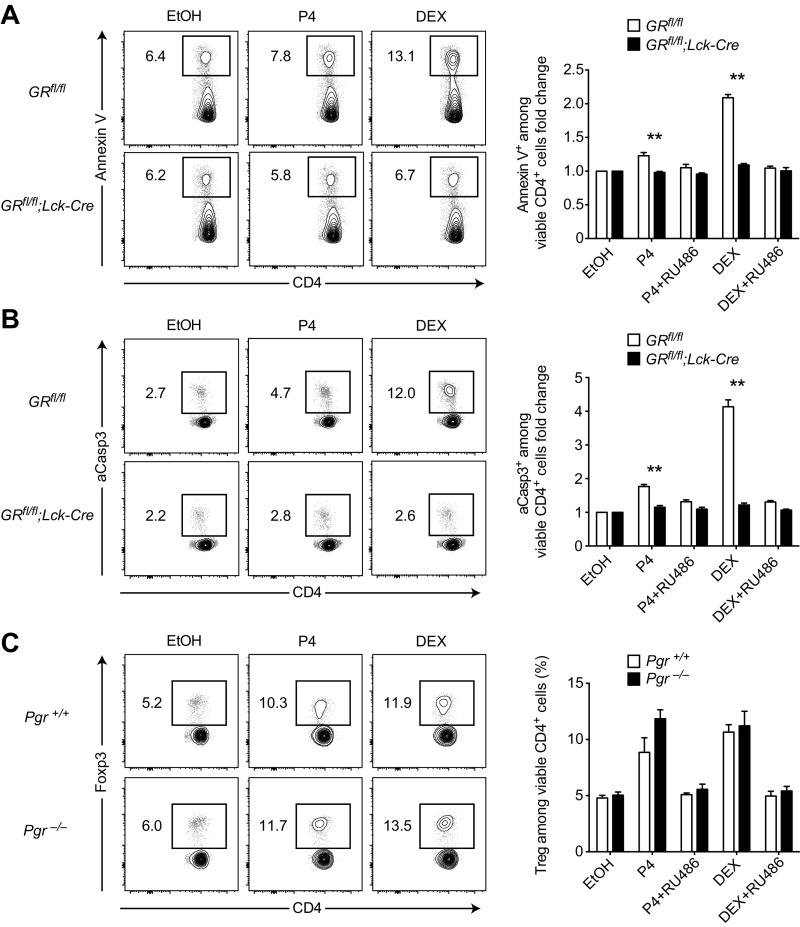

To definitely pinpoint a contribution of GR engagement to the observed Treg enrichment, we made use of a T-cell–specific GR knockout mouse. In these GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre mice the T-cell–restricted lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (Lck) promoter drives the expression of a Cre recombinase, which leads to the excision of the essential exon 3 from the GR locus, thereby disrupting GR function specifically in T cells (42–44). After ruling out a priori differences in their immune cell composition (Fig. 3C), we cultured splenocytes from GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre knockout and GRfl/fl control animals in the presence of either progesterone or DEX. Strikingly, Treg enrichment and cell death induction were completely abolished in the GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre knockout cultures, regardless of treatment with either progesterone or DEX (Fig. 3 D and E). This complete rescue in the GR knockout cultures also applied to the induction of apoptosis (Fig. S3 A and B), whereas Treg enrichment by both progesterone and DEX was still readily observed in progesterone receptor knockout cultures (Fig. S3C). In line with our previous experiments, these data support a direct action of progesterone on the GR in T cells to mediate Treg enrichment in vitro. To test the effect of GR engagement on T cells in vivo, we treated wild-type animals with a single i.p. injection of 100 µg DEX and analyzed lymph nodes and spleen 24 h later. Markedly, Treg frequencies were strongly increased by DEX in all assessed organs (Fig. S4A), whereas this effect was blocked in the GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre mice (Fig. S4B).

Fig. S3.

Targeted GR deficiency in T cells rescues steroid-driven apoptosis, whereas progesterone receptor is not required for Treg enrichment in vitro. (A) Splenocytes of GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre and GRfl/fl mice (n = 6 each) were cultured for 6 h in the presence of 300 ng⋅mL–1 progesterone (P4), 5 ng⋅mL–1 (∼10−8 M) DEX, 1 µg⋅mL–1 mifepristone (RU486), vehicle control ethanol (EtOH), or indicated combinations. Cultures were analyzed for Annexin V+ cells by flow cytometry. (B) Splenocytes of GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre and GRfl/fl mice (n = 5 each) were cultured as in A. Cultures were analyzed for aCasp3+ cells by flow cytometry. (C) Splenocytes of Pgr−/− and Pgr+/+ mice (n = 5 and n = 3, respectively) were cultured for 48 h in the presence of 300 ng⋅mL–1 progesterone (P4), 500 pg mL–1 (∼10−9 M) DEX, 1 µg⋅mL–1 mifepristone (RU486), vehicle control ethanol (EtOH), or indicated combinations. Cultures were analyzed for Treg frequency by flow cytometry. Data in A–C are pooled from two independent experiments each. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

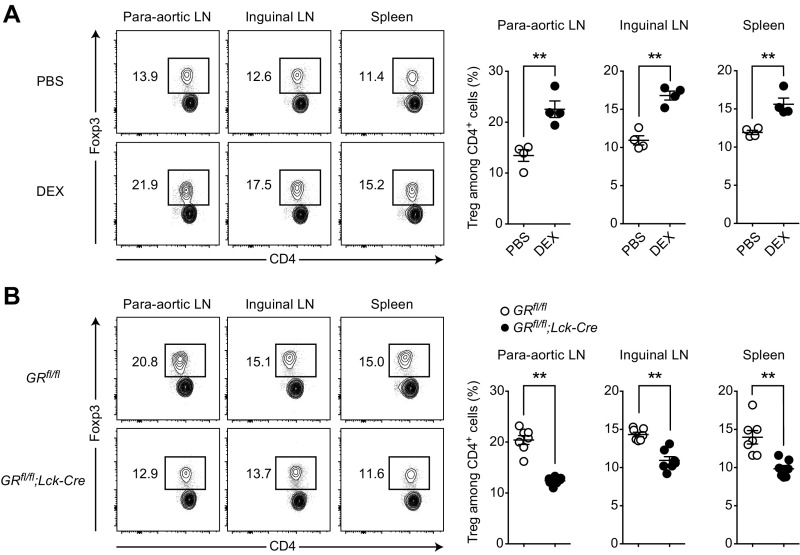

Fig. S4.

Dexamethasone increases Treg frequencies via GR in T cells in vivo. (A) Wild-type mice were treated with one i.p. injection of 100 µg DEX or vehicle control (PBS) and killed 24 h later. Paraaortic LNs, inguinal LNs, and spleen were harvested and Treg frequencies were analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre and GRfl/fl mice all treated with one i.p. injection of 100 µg DEX were analyzed as in A. Data are pooled from two independent experiments in A (total n = 4) and three independent experiments in B (total n = 7). Statistical analyses were performed by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

We conclude that Treg enrichment upon steroid challenge was mediated via the GR in T cells, whereas we found no indication for an involvement of the PR.

Tregs Are More Resistant to GR Challenge than Tcons.

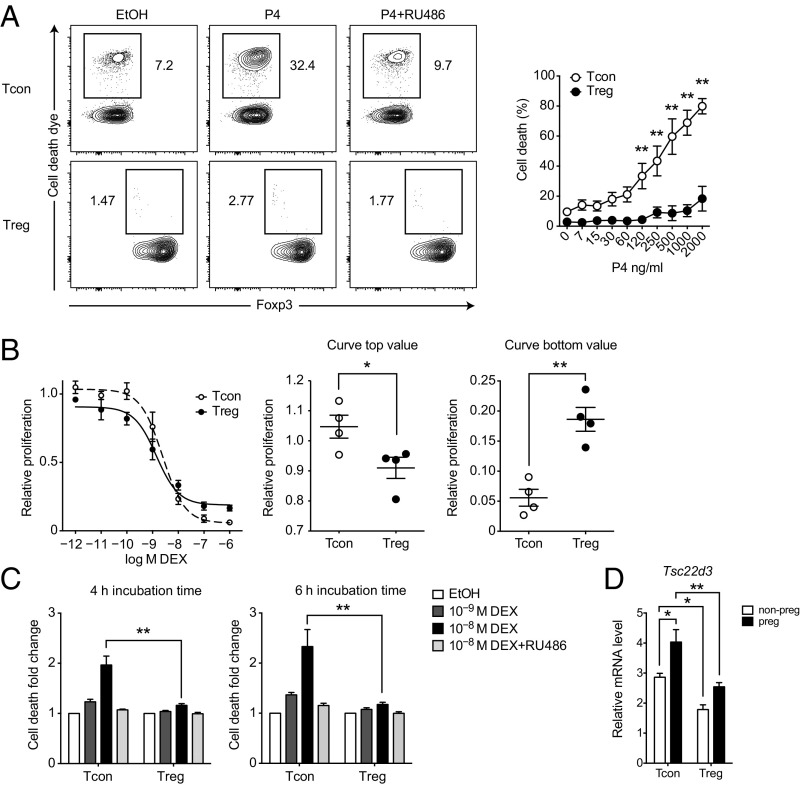

Because progesterone treatment was paralleled by increased cell death in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2 A and B), the increased Treg-to-Tcon ratio observed in vitro could be explained by an increased steroid sensitivity of Tcons in comparison with Tregs. For example, it is conceivable that Tcons are more sensitive to glucocorticoid-induced cell death, whereas Tregs are in comparison steroid resistant and hence accumulate. This notion was supported by our observation that cell death dye-positive cells were exclusively present in the Tcon but not in the Treg compartment (Fig. 4A). To further substantiate this hypothesis, we isolated Tregs and Tcons and cultured them separately in the presence of increasing doses of DEX as a potent GR stimulus. Whereas we observed more robust proliferative responses of Tcons at low concentrations of DEX (P = 0.0380), increasing GR stimulation resulted in a proliferative advantage for Tregs (P = 0.0017, Fig. 4B). Similarly, induction of cell death was more pronounced in Tcons than in Tregs when cultured under nonproliferating conditions (P < 0.0001, Fig. 4C). These findings support the idea that differential steroid sensitivity in the CD4+ T-cell compartment accounts for an enrichment of the more resistant Tregs in situations of increased GR activity.

Fig. 4.

Tregs are more resistant to GR challenge than Tcons. (A) Splenocytes were cultured for 48 h in the presence of 300 ng⋅mL–1 progesterone (P4), 1 µg⋅mL–1 mifepristone (RU486), vehicle control ethanol (EtOH), or indicated combinations. Cultures were analyzed for cell death dye positivity inside Tcon and Treg populations. (B) Proliferation response curves of Tregs and Tcons. Cells were isolated and cultured separately in the presence of irradiated feeder cells, 1 µg⋅mL–1 anti-CD3 antibody, 50 U⋅mL–1 recombinant murine IL-2, and indicated DEX concentrations. Proliferation was assessed by [3H]-thymidine incorporation and normalized to vehicle control (EtOH). Curve fit, curve top, and curve bottom values were computed. (C) Tregs and Tcons were isolated and cultured separately in the presence of DEX, 1 µg⋅mL–1 mifepristone (RU486), vehicle control ethanol (EtOH), or indicated combinations. Dead cells were identified by propidium iodide positivity and cell death was calculated as fold change relative to vehicle control (EtOH). (D) Relative mRNA levels of Gilz (encoded by Tsc22d3) in Tcons and Tregs from nonpregnant (n = 5) and pregnant (E18.5; n = 5) mice. mRNA was quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to Tbp. Data in A are reanalyzed from Fig. 2B (total n = 5). Data in B are pooled from three independent experiments (total n = 4). Data in C are pooled from three independent experiments (total n = 3). Data in D are pooled from multiple experimental days (n = 5 per group). Statistical analyses were performed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test in A, C, and D and Student’s t test in B. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

To check whether steroid levels during pregnancy are sufficient to induce transcriptional activity of the GR in CD4+ T cells in vivo, we isolated Tregs and Tcons from nonpregnant and E18.5 mice and analyzed gene expression of the glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (Gilz), encoded by Tsc22d3. We selected Gilz because its transcription is directly induced by binding of the GR to the Gilz promoter (45, 46), it mediates the antiproliferative activity of glucocorticoids (47), and can be used as a surrogate marker for GR activity. Gilz expression was significantly induced by late pregnancy in Tcons (P = 0.0207) but not in Tregs (P = 0.2496, Fig. 4D). Additionally, GR signaling was more active in Tcons irrespective of pregnancy, further supporting the notion that those cells might be a priori more susceptible to steroid challenge.

Taken together, Tregs showed a higher resistance to glucocorticoid challenges under both proliferative and nonproliferative conditions. This finding is consistent with a positive selection of Tregs as the underlying mechanism for increased Treg frequencies after GR stimulation. The GR pathway appeared to be engaged during pregnancy in vivo, because the GR target gene Gilz was induced in Tcons at E18.5.

Late Pregnancy Temporarily Protects from CNS Autoimmunity.

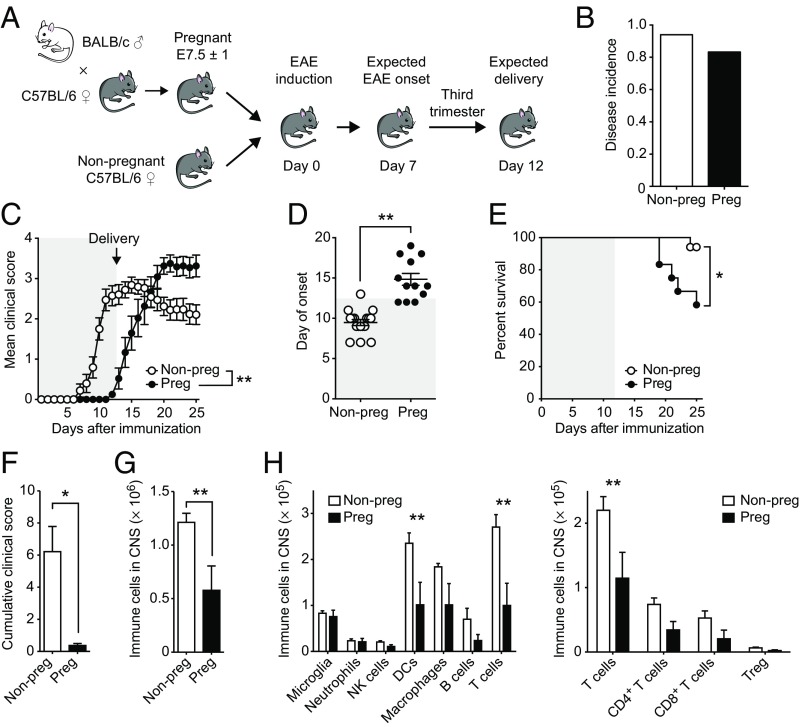

Next, we aimed to unravel whether GR activity in T cells is responsible for the beneficial effect of pregnancy on CNS autoimmunity. To this end, we first established a model of pregnancy protection from EAE in C57BL/6 mice. We performed allogeneic matings with BALB/c males and immunized at gestational day E7.5 ± 1, ensuring an estimated onset of disease at the beginning of the third trimester of pregnancy—the time point with the strongest protective effects in MS and EAE (9, 13). We expected the delivery of the pups around day 12 after immunization and included nonpregnant females as controls (Fig. 5A). Whereas the disease incidence of both groups was indistinguishable (P = 0.5681, Fig. 5B), pregnant animals were protected until the day of delivery. Immediately after birth of the pups, the dams succumbed to an exaggerated disease course associated with increased motor disability and higher mortality, reminiscent of the overshooting disease activity observed in MS patients postpartum (Fig. 5 C–E) (9, 11).

Fig. 5.

Late pregnancy temporarily protects from CNS autoimmunity. (A) Experimental setup of pregnancy EAE. Disease incidence (B), clinical course (C), day of onset (D), and survival (E) are shown for nonpregnant (n = 17) and pregnant (n = 12) animals. Gray shaded areas represent pregnancy. (F–H) Nonpregnant (n = 4) and pregnant (n = 8) animals were killed on day 10 after EAE induction. Cumulative clinical score (F) and absolute numbers of immune cells (G) and immune cell subpopulations in the CNS (H) were assessed by flow cytometry. Data in B–E are pooled from four independent experiments. Data in F–H show one representative experiment out of two. Statistical analyses were performed by Fisher’s exact test in B, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test in C and H, Student’s t test in D, F, and G, and χ2 test in E. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Because motor function defects assessed during EAE can be attributed to inflammatory injury of responsible neurons and their projections (48, 49), we next assessed the infiltration of immune cells into the CNS during the protective period (at day 10) by flow cytometry. At this time point, pregnant animals were clinically asymptomatic (Fig. 5F) and showed half the absolute number of immune cells in the CNS (P = 0.0089, Fig. 5G), suggesting a peripheral control of encephalitogenic cells, whereas particularly T cells and dendritic cells (DCs) were reduced in pregnant EAE brains (Fig. 5H).

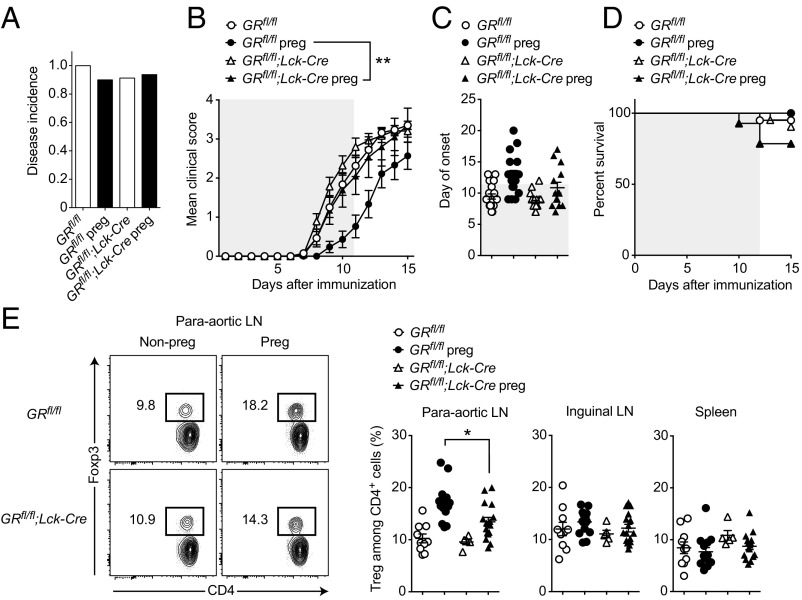

The GR in T Cells Mediates EAE Protection During Pregnancy but Is Dispensable for Reproductive Success.

To assess the biological role of GR in T cells in mediating the protective effect of pregnancy in CNS autoimmunity, we performed allogeneic matings of GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre knockout and GRfl/fl control animals and induced EAE on gestational day E7.5 ± 1. We observed no differences in the disease incidence (Fig. 6A). However, as expected from our initial experiments, pregnancy resulted in a protection of GRfl/fl control mice. By contrast, the EAE protection was abolished in pregnant GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre knockout mice (P = 0.003, Fig. 6B), whereas we found no evidence for an a priori exacerbated EAE in GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre knockout animals when comparing the nonpregnant groups (Fig. 6 B–D). Thus, protection from EAE in pregnant mice depended on the presence of the GR in T cells. Additionally, Treg frequencies in pregnant GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre knockout animals with EAE (E18.5) were reduced in comparison with pregnant EAE controls in paraaortic lymph nodes (P = 0.0144, Fig. 6E), suggesting an impaired Treg expansion. Although pregnancy still showed a tendency to increase Tregs in GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre mice, this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.1023, Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

The GR in T cells mediates EAE protection during pregnancy. (A–D) EAE was induced in nonpregnant and pregnant GRfl/fl (n = 20 and n = 18, respectively) and nonpregnant and pregnant GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre mice (n = 21 and n = 14, respectively). Disease incidence (A), clinical course (B), day of onset (C), and survival (D) are shown. Gray shaded areas represent pregnancy. (E) Treg frequency in nonpregnant and pregnant GRfl/fl (n = 10 and n = 14, respectively) and nonpregnant and pregnant GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre mice (n = 5 and n = 16, respectively) treated as in A–D were killed at E18.5 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are pooled from four independent experiments in A–D and three independent experiments in E. Statistical analyses were performed by Fisher’s exact test in A; two-way ANOVA in B; one-way ANOVA in C and E, all with Bonferroni’s post hoc test; and χ2 test in D. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

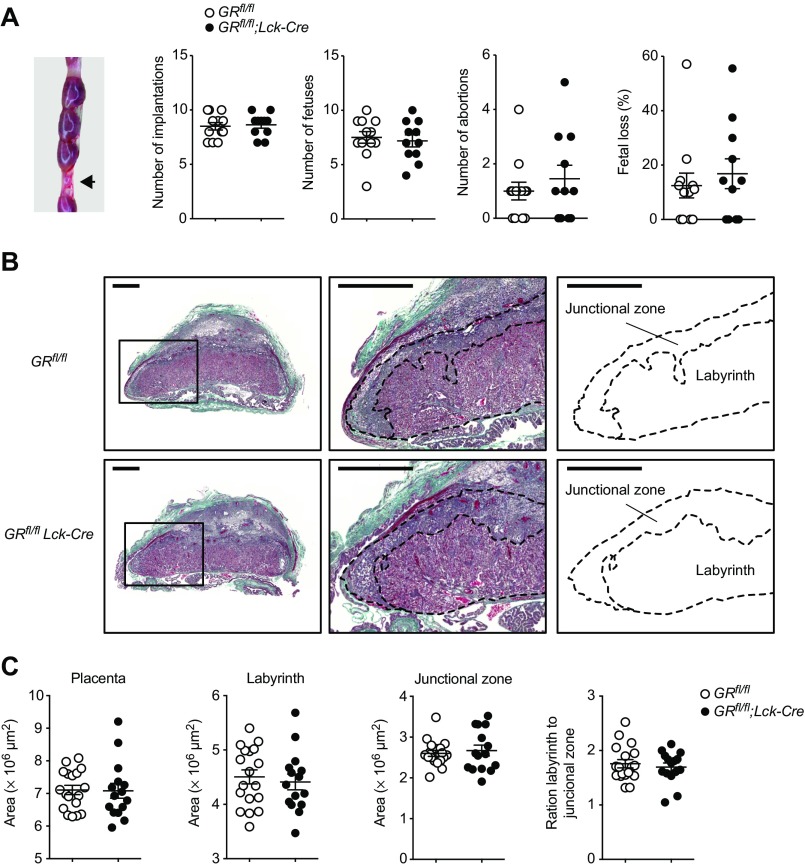

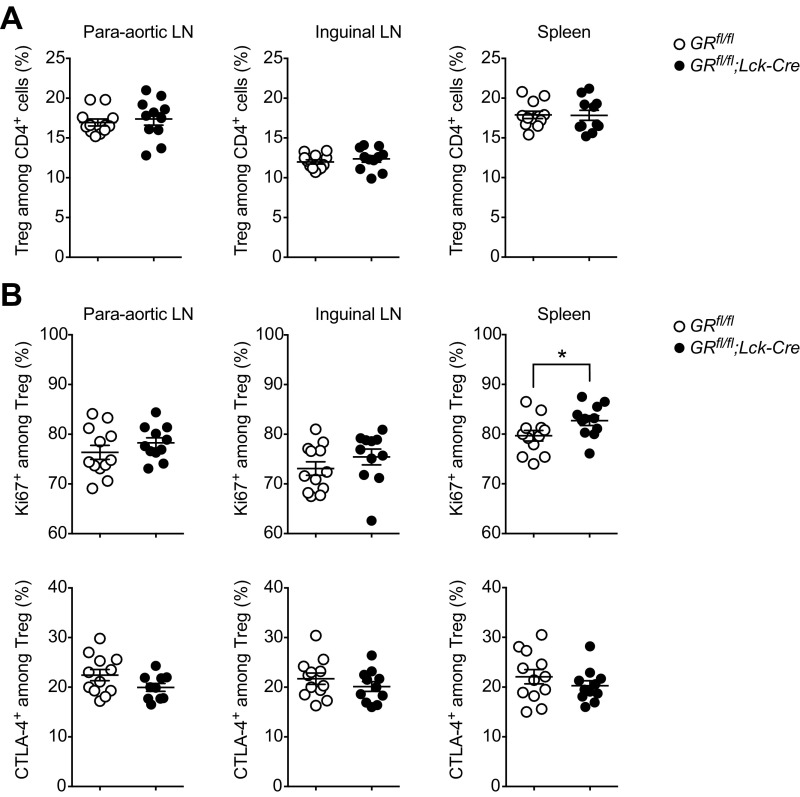

To investigate the possibility that a failure in fetomaternal tolerance with consecutive fetal loss could have caused this breakdown of EAE protection as a secondary effect, we killed GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre mice and controls at E13.5–14.5 and analyzed reproductive outcome parameters, including fetal loss and placental morphology. However, all assessed parameters, including Treg frequencies, were unchanged in GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre mice (Figs. S5 and S6). Thus, fetomaternal tolerance appeared to be more stable than pregnancy-induced autoantigen tolerance.

Fig. S5.

The GR in T cells is dispensable for reproductive success. (A) Reproductive phenotype was assessed at E13.5–14.5 by macroscopically inspecting the pregnant uterus of GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre and GRfl/fl control mice. Implantations, fetuses, and abortions were counted. Fetal loss was calculated as abortions per implantations per mother. Each dot represents one pregnant mouse. Exemplary abortion site is shown on the Left (arrow). (B) Representative placental morphology at E13.5 with identification of labyrinth and junctional zone. (Scale bar, 1 mm.) (C) Quantification of placental morphology. Per pregnant mouse, three placentas have been collected and analyzed. Each dot represents one placenta. Data in A are pooled from two independent experiments at E13.5 (n = 6 vs. 5) and E14.5 (n = 6 vs. 5). Data in B and C are representative of one experiment (n = 6 vs. 5 pregnant mice). Statistical analyses were performed by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Fig. S6.

Treg frequencies and phenotype in GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre mice at midpregnancy. Treg frequencies (A) and phenotype (B) were analyzed by flow cytometry at E13.5–14.5 in the same animals presented in Fig. S5. Each dot represents one pregnant mouse. Data are pooled from two independent experiments at E13.5 (n = 6 vs. 5) and E14.5 (n = 6 vs. 5). Statistical analyses were performed by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Discussion

In the present study, we have in detail characterized shifts in the T-cell compartment during pregnancy with a specific focus on the immunological balance of Tcons and Tregs and the endocrine mechanisms orchestrating them. Our findings indicate that pregnancy-related steroid hormones are directly sensed by T cells and mediate a relative enrichment of Tregs via engagement of the GR. Intriguingly, our conditional GR knockout model demonstrated that steroid hormone sensing by T cells is crucial for conferring protection from maternal autoimmunity in late gestation. However, establishment of fetomaternal tolerance itself, reflected by reproductive success, did not depend on the presence of GR in T cells.

Although Treg-driven tolerance has been shown to be fetal antigen specific in the first place (22), it has also been noted that Tregs are able to suppress T-cell responses to unrelated antigens in the form of a bystander suppression (50). This can have detrimental consequences as Treg expansion leaves pregnant mice more prone to infections with certain pathogens including Listeria and Salmonella species, whereas Treg depletion has been shown to restore host defense (23). Thus, enhanced Treg-driven control of effector T-cell responses in pregnancy represents a promising target when studying tolerogenic off-target effects, as it might be the case in pregnancy-induced reduction of autoimmunity.

Herein, we characterized Tregs and Tcons in C57BL/6 females mated to BALB/c males and observed a marked late gestational Treg expansion in the local paraaortic LNs that directly drain the uterus and constitute the place of fetal-specific T-cell priming (2, 51). Similar findings have been reported by other groups pioneering the investigation of Tregs in the context of reproductive biology (18, 23, 52). Notably, increased Treg frequencies persisted even after delivery. This finding is in concordance with a study using a mating system with known paternal antigen to show that fetal-specific Tregs can persist as regulatory memory cells that readily reassemble in a consecutive pregnancy (22). Beyond that, we identified proliferative bursts in Tregs that appear to reflect a local priming event driven by male seminal fluid (51) in early gestation and a systemic challenge to fetus-derived antigens shed into the mother’s circulation (52, 53) in late gestation.

However, the most dramatic changes in Treg frequency and phenotype at E18.5 were directly preceded by the peak progesterone levels present around E16.5 (38). A number of studies have implied that progesterone can support Tregs and dampen effector responses, without providing a clear molecular mechanism. These include observations that s.c. progesterone-releasing implants at the onset of disease ameliorate the course of EAE in C57BL/6 mice, however, without altering the systemic frequency of Tregs (40). In contrast, another study reported a substantial increase of uterine and systemic Treg frequencies when treating ovariectomized mice with s.c. injection of progesterone (24). Additionally, progesterone was shown to drive naïve human cord blood cells but not adult peripheral T cells into suppressive Tregs while impeding their differentiation into TH17 cells (25).

Thus, we addressed the questions of whether progesterone is capable of shifting the balance in the T-cell compartment in favor of Tregs and whether we could set up a stable assay to decipher the underlying molecular mechanism. Indeed, we observed a robust increase of Treg frequencies after treating splenocyte cultures for 48 h with 300 ng⋅mL–1 progesterone, which corresponds to approximately three times the serum level present at E16.5 (38). We consider this level close to the physiological range, as we would anticipate similar local levels close to the fetomaternal interface.

To our surprise however, we found no evidence for PR expression in CD4+ T cells on the mRNA level, representing the primary progesterone target. This finding is in agreement with data from the Immunological Genome Project (54) providing Pgr expression levels that do not exceed the detection background. By a series of experiments, we could finally attribute the effect to a cross engagement of the GR in T cells. The strongest piece of evidence in this regard is the complete abrogation of Treg enrichment in cultures from T-cell–restricted GR knockout mice (GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre). This evidence suggests that T cells sense progesterone via their intracellular GR, leading to an increase of Treg frequencies. Being engaged in times of increased steroid serum levels, this finding represents a so-far unrecognized tolerogenic pathway that might shape the immunological balance during pregnancy. Clearly, this mechanism is not restricted to progesterone, but rather includes the action of corticosterone and other steroid hormones with agonistic potential on the GR that equally increase during the course of gestation (55).

Mechanistically, we found that Tregs are more resistant to steroid challenges in comparison with Tcons, thus possessing a survival advantage in times of increased steroid levels. Hence, the observed enrichment of Tregs is likely the result of a selection of resistant Tregs, whereas sensitive Tcons succumbed to glucocorticoid-induced cell death. This interpretation is also in agreement with increasing rates of apoptosis and cell death in CD4+ cells paralleling the Treg enrichment in dose and time-course experiments. Importantly, targeted inhibition of apoptosis reduced the Treg enrichment, further supporting this notion. Whereas apoptosis induction in leukocytes by DEX is well established (56), there have only been incidental reports for progesterone (57). Furthermore, we observed increased Gilz expression in Tcons isolated from pregnant animals, indicating that GR activity is induced during pregnancy in these cells, but to a lesser extent in the more resistant Tregs.

To investigate the relevance of this mechanism for the amelioration of autoimmunity during in vivo pregnancy, we established a mouse model in which pregnant animals are protected from EAE until delivery. Strikingly, whereas the protection conferred by pregnancy is among the strongest beneficial regulators of autoimmunity, this effect was completely abrogated in GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre knockout animals, supporting a central role of GR signaling in ensuring proper maintenance of pregnancy-related CNS-autoantigen tolerance. Accordingly, the Treg expansion in paraaortic LNs present in pregnant controls was diminished in pregnant GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre knockout animals during EAE. Our results extend previous evidence supporting the crucial role of intact GR signaling in T cells for the control of neuroinflammation (58). It has been also reported that deletion of the GR in T cells abolishes the therapeutic effect of dexamethasone in mice (59, 60), whereas overexpression of the GR in thymocytes ameliorates EAE in a rat model (61). Here, we show that pregnancy endogenously employs this pathway to exert its protective effects on maternal autoimmunity.

Additionally, we provide evidence that the GR in T cells is of particular importance for mediating amelioration of maternal autoimmune responses but not for ensuring fetomaternal tolerance as deletion of the GR in T cells completely abrogated the protective effect of pregnancy on EAE but had no impact on any assessed measures of reproduction. Notably, also Treg expansion found to be disturbed in GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre knockout animals in EAE pregnancy was unaltered in mid term pregnancy without EAE. These findings likely reflect the high stability of reproduction and Treg expansion, which are ensured by redundant mechanisms in the absence of inflammatory challenges (1, 5). In line with this redundancy, it usually takes more than one hit to cause severe reproductive failure, as evidenced by a number of mutant mice with largely unaltered reproductive success (1). This result is likely due to high evolutionary pressure on successful species propagation via reproduction (62). In contrast, controlling chronic inflammation in autoimmune diseases seems to be a more fragile side effect that requires all reproductive tolerance mechanisms to fully operate.

Some limitations of this study have to be considered. Whereas our data clearly demonstrate that GR signaling in T cells is indispensable for pregnancy protection from EAE, this does not rule out additional protective mechanisms of pregnancy exerted by other factors such as estrogens, which have shown promise in clinical trials in MS (63–65). Furthermore, because we show that successful reproduction does not critically rely on GR signaling in T cells, it needs to be further elucidated on what basis differential effects on reproductive and autoimmune tolerance are mediated.

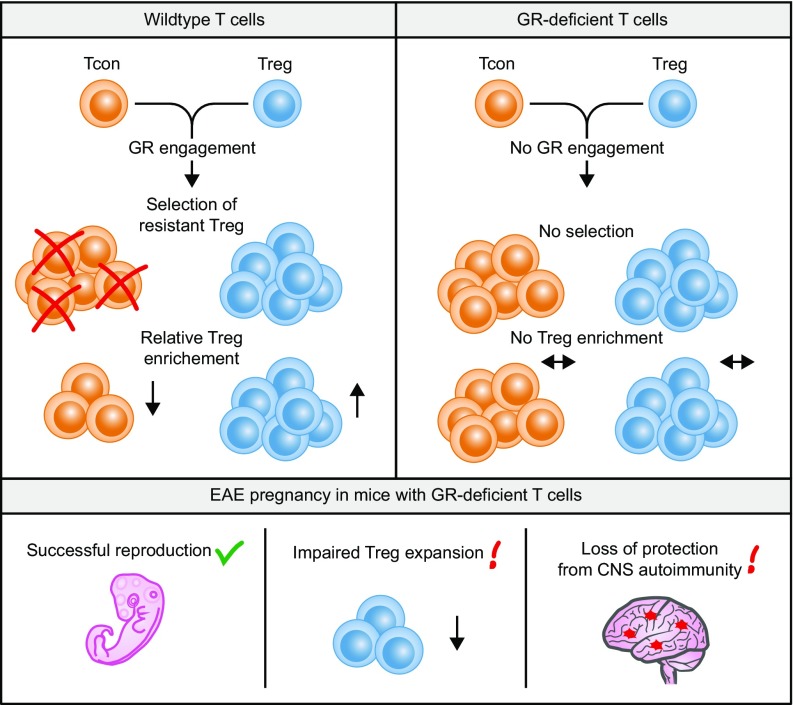

Summarizing our findings, we provide evidence that differential steroid sensitivity of Tregs and Tcons represents a so-far unrecognized tolerance mechanism that might be engaged in times of high steroid levels, as present during gestation (Fig. 7). We show that this pathway works via promiscuous binding of progesterone to the GR in T cells and is able to enrich Tregs in vitro. Furthermore, we found evidence that GR signaling is in fact operative in Tcons during pregnancy in vivo, whereas T-cell–specific GR deletion resulted in a loss of pregnancy-induced protection from EAE and reduced Treg frequencies in uterus-draining LNs. However, further work is needed to disentangle the molecular basis of the differential sensitivity of Tregs and Tcons. Better understanding the T-cell population-specific prerequisites that communicate this differential sensitivity holds the promise to yield more specific therapeutic means to steer the immunological balance in transplantation, cancer, and autoimmunity.

Fig. 7.

Differential steroid sensitivity as a mechanism of tolerance induction. Upon GR engagement steroid-resistant Tregs are positively selected and hence accumulate. After targeted GR disruption in T cells, Tcons and Tregs are equally resistant to GR engagement, thus the enrichment of Treg is abolished. In pregnant EAE animals harboring GR-deficient T cells, reproduction is still functional. However, Tregs increase and pregnancy-associated protection from autoimmune disease activity is impaired.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6 wild-type mice (The Jackson Laboratory) and previously described GRfl/fl;Lck-Cre (Nr3c1tm2GSc;Tg(Lck-cre)1Cwi) mice (42–44) and Pgr−/− mice (66) were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Central Animal Facility at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. Age- and sex-matched adult animals (10–20 wk) were used in all experiments.

Dexamethasone Treatment.

Mice were treated with one i.p. injection of 100 µg (∼5 mg per kilogram of body weight) dexamethasone (Fortecortin Inject, MerckSerono) in PBS or vehicle control (PBS) and killed 24 h later.

Allogeneic Mating.

Age-matched female mice were primed with housing material from fertile BALB/c males for 1 wk and then mated for three consecutive nights. Successfully mated females where identified by the presence of a vaginal plug, separated, and weighted daily to confirm pregnancy. The day of plug was considered gestational day 0.5 (E0.5). In experiments including postpartum time points, pups were separated and killed at the day of delivery.

EAE Induction.

Mice were immunized s.c. with 200 μg MOG35–55 peptide (Schafer-N) in complete Freund’s adjuvant (Difco) containing 4 mg⋅mL–1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Difco). In addition, 200 ng pertussis toxin (Calbiochem) was injected i.v. on the day of immunization and 48 h later. Animals were scored daily for clinical signs by the following system: 0, no clinical deficits; 1, tail weakness; 2, hind limb paresis; 3, partial hind limb paralysis; 3.5, full hind limb paralysis; 4, full hind limb paralysis and forelimb paresis; and 5, premorbid or dead. Animals reaching a clinical score ≥4 had to be killed according to the regulations of the Animal Welfare Act. The last observed score of euthanized or dead animals was carried forward for statistical analysis. The cumulative clinical score represents the sum of the daily scores given to an animal over time. Investigators were blinded for genotype during the experiment.

Immune Cell Isolation from Lymphoid Organs and CNS.

Mice were killed by inhalation of CO2 and lymph nodes and spleens were harvested with sterile instruments into ice-cold PBS. Single-cell suspensions were prepared by homogenization through a 40-µm cell strainer, cells were pelleted by centrifugation (300 × g, 10 min, 4 °C), and splenic erythrocytes were lysed in red blood cell lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, pH = 7.4) for 5 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed with PBS and used in follow-up applications. For isolation of CNS-infiltrating leukocytes, mice were intracardially perfused with ice-cold PBS immediately after killing to remove blood from intracranial vessels. Brain and spinal cord were prepared with sterile instruments, minced with a scalpel, and incubated with agitation in RPMI medium 1640 (PAA) containing 1 mg⋅mL–1 collagenase A (Roche) and 0.1 mg⋅mL–1 DNaseI (Roche) for 60 min at 37 °C. Tissue was triturated through a 40-µm cell strainer and washed with PBS (300 × g, 10 min, 4 °C). Homogenized tissue was resuspended in 30% isotonic Percoll (GE Healthcare) and carefully underlaid with 78% isotonic Percoll. After gradient centrifugation (1,500 × g, 30 min, 4 °C) CNS-infiltrating immune cells were recovered from the gradient interphase and washed twice in ice-cold PBS before staining for flow cytometry.

Flow Cytometry Analysis.

Single-cell suspensions were stained in the presence of TruStain Fc receptor block (BioLegend) with monoclonal antibodies directed against CD3e (PerCP-Cy5.5, BioLegend, clone 145–2C11), CD4 (PE-Cy7, eBioscience, clone GK1.5), CD8a (Pacific blue, BioLegend, clone 53–6.7), CD11b (FITC, BioLegend, clone M1/70), CD11c (PE-Cy7, eBioscience, clone N418), CD25 (Alexa Fluor 488 and APC, eBioscience, clone PC61.5), CD45 (APC-Cy7, BioLegend, clone 30-F11), CD45R (V500, BD Horizon, clone RA3-6B), Ctla4 (APC, eBioscience, clone UC10-4B9), Foxp3 (PE and eFluor 450, eBioscience, clone FJK-16s), Ly6G (V450, BD Biosciences, clone 1A8), NK1.1 (PE, eBioscience, clone PK136), aCasp3 (FITC, BD Biosciences, clone C92-605), and Ki67 (PE, BD Biosciences, clone B56) and acquired on a LSR II FACS analyzer (BD). In indicated experiments, dead cells were labeled before surface staining with Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit (Life Technologies). For intracellular staining of Foxp3, Ctla4, and Ki67, the Foxp3 Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For detection of apoptosis, the Active Caspase-3 Apoptosis Kit (BD Biosciences) and FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BioLegend) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absolute cell counts of CD45+ CNS-infiltrating leukocytes were determined by using TrueCount tubes (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed with FlowJo v10 analysis software (TreeStar) for Macintosh. Tregs were identified as CD4+Foxp3+ and Tcons as CD4+Foxp3– cells. Additional immune cell populations from splenocytes and CNS-infiltrating cells were identified as previously reported (49).

Isolation of T-Cell Populations.

Pooled single-cell suspensions from inguinal, axillary, brachial, paraaortic lymph nodes, and spleen were subjected to magnetic-associated cell sorting (MACS) using the CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) or CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purity of isolated cells was routinely above 80% for CD4 T cells and above 90% for Tregs and Tcons.

Steroid Assay.

Isolated splenocytes were cultured in complete medium (RPMI 1640, 10% FCS, 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U⋅mL–1 penicillin/streptomycin) at a cell density of 0.5 × 106 cells per well in a 96-well round bottom plate for a period of 48 h, unless otherwise stated. Progesterone, DEX, D(–)norgestrel, estradiol (E2), mifepristone (RU486), or vehicle control ethanol (all Sigma) were added at indicated concentrations. In selected experiments, cells were preincubated with 10 µM caspase 3 inhibitor Z-DEVD-FMK (BD Biosciences) for 30 min. Four to six replicate wells were pooled per condition and subjected to antibody staining for flow cytometry analysis of viable cells.

Apoptosis Assay.

Isolated splenocytes were cultured in complete medium at a cell density of 0.5 × 106 cells per well in a 96-well round bottom plate for a period of 6 h. Progesterone, DEX, mifepristone (RU486), or vehicle control ethanol (all Sigma) were added at indicated concentrations. Four to six replicate wells were pooled per condition and subjected to Annexin V and aCasp3 staining for flow cytometry analysis of viable cells.

Proliferation Assay.

T-cell–depleted nonproliferative feeder cells were generated by adding 100 µL LowTox Rabbit Complement M (Cedarlane) and 5 µL of rat anti-mouse CD90.2 (BioLegend, clone30-H12) to 30 × 106 wild-type splenocytes resuspended in 900 µL HBSS medium (PAA). After incubation with mild agitation for 30 min at 37 °C, cells were washed twice with ice-cold HBSS (300 × g, 10 min, 4 °C), irradiated with 35 Gy in a Biobeam 2000 gamma irradiator (Eckert & Ziegler), washed twice with ice-cold HBSS, and used as irradiated feeder cells. Tregs and Tcons were isolated by MACS as described above and cultured separately in complete medium at 5 × 104 cells per well in the presence of 5 × 104 irradiated feeder cells per well in 96-well round bottom plates. Cultures were stimulated for proliferation with 1 µg⋅mL–1 hamster anti-mouse CD3 antibody (BioLegend, clone 145–2C11) in the presence of 50 U⋅mL–1 recombinant murine IL-2 (eBioscience) and increasing concentrations of dexamethasone. All experimental conditions were plated in technical triplicates and adjusted to a final volume of 200 µL per well. After 48 h, cells were pulsed with 1 μCi [3H]-thymidine (Amersham) per well for 16 h. Then, cells were harvested and spotted on filter mats with a Harvester 96 MACH III M (Tomtec). Incorporated activity per well was assessed in counts per minute (cpm) in a beta counter (1450 Microbeta, Perkin-Elmer) and proliferation was calculated relative to the mean of nondexamethasone-treated control wells. Curve fit and curve statistics were computed using Prism 6 software (Graphpad) for Macintosh.

Cell Death Assay.

Tregs and Tcons were isolated by MACS and cultured separately in complete medium at 1 × 105 cells per well in 96-well round bottom plates. Dexamethasone, mifepristone (RU486), or vehicle control ethanol were added at indicated concentrations. Dead cells were identified by positivity for propidium iodide (BioLegend) after 4 h and 6 h culture time. Cell death fold change was calculated relative to vehicle control.

Gene Expression Analysis.

RNA was purified using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed to cDNA with RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression was analyzed by real-time PCR performed in an ABI Prism 7900 HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Life Technologies) for the following targets: estrogen receptor (Esr1, Mm00433149_m1), GR (Nr3c1, Mm00433832_m1), PR (Pgr, Mm00435628_m1), Gilz (Tsc22d3, Mm01306210_g1), and TATA-box binding protein (Tbp, Mm00446971_m1). Gene expression was calculated as 2−ΔCT relative to Tbp as endogenous control.

Histomorphological Analyses of Placental Tissue.

Paraffin-embedded placental tissue was cut into 3- to 6-μm histological sections at the midsagittal plane using a microtome (Leica). Tissue sections were deparaffinized, rinsed in distilled water, and dehydrated twice in ethanol (70%). Masson-Goldner Trichrome Staining Kit (VWR International) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to visualize the morphologically different areas of placental tissue. Briefly, tissue sections were stepwise stained with Weigert’s iron hematoxylin, azophloxine staining solution, phosphotungstic acid orange G, and light-green SF solution. Finally, the tissue was dehydrated and mounted using Eukitt medium (O. Kindler). Image acquisition was performed using a slide scanner (Mirax Midi, Zeiss). Areas of junctional zone and labyrinth zones were quantified using the program MiraxViewer.

Statistics.

Data were analyzed using Prism 6 software (GraphPad) for Macintosh and are presented as mean values ± SEM. All n values refer to the number of biological replicates, that is, individual mice. Differences between two experimental groups were determined by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. Comparison of three or more groups was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Statistical analysis comparing two groups under multiple conditions or over time was performed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. In two-way ANOVA analysis of EAE disease courses, the P value for group × time interaction is reported. Differences in disease incidence and survival were assessed by Fisher’s exact test and χ2 test, respectively. Significant results are indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Study Approval.

All animal care and experimental procedures were carried out according to institutional guidelines and conformed to requirements of the German Animal Welfare Act. Ethical approvals were obtained from the State Authority of Hamburg, Germany (approval G12/012).

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristin Thiele for breeding and providing the Pgr−/− mice. This work was supported by grants (to M.A.F. and S.M.G.) from the Forschungs- und Wissenschaftsstiftung Hamburg and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FR1720/8-1 and GO1357/8-1, KFO296 Fetomaternal Immune Cross-Talk).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1617115114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Arck PC, Hecher K. Fetomaternal immune cross-talk and its consequences for maternal and offspring’s health. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):548–556. doi: 10.1038/nm.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins MK, Tay C-S, Erlebacher A. Dendritic cell entrapment within the pregnant uterus inhibits immune surveillance of the maternal/fetal interface in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(7):2062–2073. doi: 10.1172/JCI38714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blois SM, et al. A pivotal role for galectin-1 in fetomaternal tolerance. Nat Med. 2007;13(12):1450–1457. doi: 10.1038/nm1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nancy P, et al. Chemokine gene silencing in decidual stromal cells limits T cell access to the maternal-fetal interface. Science. 2012;336(6086):1317–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.1220030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erlebacher A. Mechanisms of T cell tolerance towards the allogeneic fetus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(1):23–33. doi: 10.1038/nri3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Man YA, Dolhain RJEM, van de Geijn FE, Willemsen SP, Hazes JMW. Disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: Results from a nationwide prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1241–1248. doi: 10.1002/art.24003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Förger F, et al. Pregnancy induces numerical and functional changes of CD4+CD25 high regulatory T cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(7):984–990. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.075283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchel E, Van Steenbergen W, Nevens F, Fevery J. Improvement of autoimmune hepatitis during pregnancy followed by flare-up after delivery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(12):3160–3165. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vukusic S, et al. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): Clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 6):1353–1360. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours MM, Cortinovis-Tourniaire P, Moreau T. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(5):285–291. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelsztejn A, Brooks JBB, Paschoal FM, Jr, Fragoso YD. What can we really tell women with multiple sclerosis regarding pregnancy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. BJOG. 2011;118(7):790–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dendrou CA, Fugger L, Friese MA. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(9):545–558. doi: 10.1038/nri3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langer-Gould A, Garren H, Slansky A, Ruiz PJ, Steinman L. Late pregnancy suppresses relapses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: Evidence for a suppressive pregnancy-related serum factor. J Immunol. 2002;169(2):1084–1091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gatson NN, et al. Induction of pregnancy during established EAE halts progression of CNS autoimmune injury via pregnancy-specific serum factors. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;230(1–2):105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClain MA, et al. Pregnancy suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis through immunoregulatory cytokine production. J Immunol. 2007;179(12):8146–8152. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voskuhl RR, Palaszynski K. Sex hormones in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: Implications for multiple sclerosis. Neuroscientist. 2001;7(3):258–270. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: From molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38(6):709–718. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0584-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aluvihare VR, Kallikourdis M, Betz AG. Regulatory T cells mediate maternal tolerance to the fetus. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(3):266–271. doi: 10.1038/ni1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zenclussen AC, et al. Regulatory T cells induce a privileged tolerant microenvironment at the fetal-maternal interface. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(1):82–94. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(4):345–352. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patas K, Engler JB, Friese MA, Gold SM. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: Feto-maternal immune cross talk and its implications for disease activity. J Reprod Immunol. 2013;97(1):140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe JH, Ertelt JM, Xin L, Way SS. Pregnancy imprints regulatory memory that sustains anergy to fetal antigen. Nature. 2012;490(7418):102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature11462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowe JH, Ertelt JM, Aguilera MN, Farrar MA, Way SS. Foxp3(+) regulatory T cell expansion required for sustaining pregnancy compromises host defense against prenatal bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10(1):54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao G, et al. Progesterone increases systemic and local uterine proportions of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells during midterm pregnancy in mice. Endocrinology. 2010;151(11):5477–5488. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JH, Ulrich B, Cho J, Park J, Kim CH. Progesterone promotes differentiation of human cord blood fetal T cells into T regulatory cells but suppresses their differentiation into Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2011;187(4):1778–1787. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wildin RS, et al. X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):18–20. doi: 10.1038/83707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett CL, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humrich JY, et al. Homeostatic imbalance of regulatory and effector T cells due to IL-2 deprivation amplifies murine lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(1):204–209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903158107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engler JB, et al. Unmasking of autoreactive CD4 T cells by depletion of CD25 regulatory T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(12):2176–2183. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.153619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nie H, et al. Phosphorylation of FOXP3 controls regulatory T cell function and is inhibited by TNF-α in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med. 2013;19(3):322–328. doi: 10.1038/nm.3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munoz-Suano A, Kallikourdis M, Sarris M, Betz AG. Regulatory T cells protect from autoimmune arthritis during pregnancy. J Autoimmun. 2012;38(2–3):J103–J108. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baca Jones C, et al. Regulatory T cells control diabetes without compromising acute anti-viral defense. Clin Immunol. 2014;153(2):298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viglietta V, Baecher-Allan C, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Loss of functional suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2004;199(7):971–979. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carbone F, et al. Regulatory T cell proliferative potential is impaired in human autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2014;20(1):69–74. doi: 10.1038/nm.3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sellebjerg F, Krakauer M, Khademi M, Olsson T, Sørensen PS. FOXP3, CBLB and ITCH gene expression and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 expression on CD4(+) CD25(high) T cells in multiple sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;170(2):149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huan J, et al. Decreased FOXP3 levels in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81(1):45–52. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venken K, et al. Compromised CD4+ CD25(high) regulatory T-cell function in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis is correlated with a reduced frequency of FOXP3-positive cells and reduced FOXP3 expression at the single-cell level. Immunology. 2008;123(1):79–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02690.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holinka CF, Tseng YC, Finch CE. Reproductive aging in C57BL/6J mice: Plasma progesterone, viable embryos and resorption frequency throughout pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 1979;20(5):1201–1211. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod20.5.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solano ME, et al. Progesterone and HMOX-1 promote fetal growth by CD8+ T cell modulation. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(4):1726–1738. doi: 10.1172/JCI68140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yates MA, et al. Progesterone treatment reduces disease severity and increases IL-10 in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;220(1–2):136–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ojasoo T, Doré JC, Gilbert J, Raynaud JP. Binding of steroids to the progestin and glucocorticoid receptors analyzed by correspondence analysis. J Med Chem. 1988;31(6):1160–1169. doi: 10.1021/jm00401a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tronche F, et al. Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nat Genet. 1999;23(1):99–103. doi: 10.1038/12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orban PC, Chui D, Marth JD. Tissue- and site-specific DNA recombination in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(15):6861–6865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baumann S, et al. Glucocorticoids inhibit activation-induced cell death (AICD) via direct DNA-dependent repression of the CD95 ligand gene by a glucocorticoid receptor dimer. Blood. 2005;106(2):617–625. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.John S, et al. Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nat Genet. 2011;43(3):264–268. doi: 10.1038/ng.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Laan S, et al. Chromatin immunoprecipitation scanning identifies glucocorticoid receptor binding regions in the proximal promoter of a ubiquitously expressed glucocorticoid target gene in brain. J Neurochem. 2008;106(6):2515–2523. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayroldi E, et al. GILZ mediates the antiproliferative activity of glucocorticoids by negative regulation of Ras signaling. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(6):1605–1615. doi: 10.1172/JCI30724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikić I, et al. A reversible form of axon damage in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2011;17(4):495–499. doi: 10.1038/nm.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schattling B, et al. TRPM4 cation channel mediates axonal and neuronal degeneration in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2012;18(12):1805–1811. doi: 10.1038/nm.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kahn DA, Baltimore D. Pregnancy induces a fetal antigen-specific maternal T regulatory cell response that contributes to tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(20):9299–9304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003909107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robertson SA, et al. Seminal fluid drives expansion of the CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cell pool and induces tolerance to paternal alloantigens in mice. Biol Reprod. 2009;80(5):1036–1045. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.074658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moldenhauer LM, et al. Cross-presentation of male seminal fluid antigens elicits T cell activation to initiate the female immune response to pregnancy. J Immunol. 2009;182(12):8080–8093. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Erlebacher A, Vencato D, Price KA, Zhang D, Glimcher LH. Constraints in antigen presentation severely restrict T cell recognition of the allogeneic fetus. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(5):1399–1411. doi: 10.1172/JCI28214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heng TSP, Painter MW. Immunological Genome Project Consortium The Immunological Genome Project: Networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(10):1091–1094. doi: 10.1038/ni1008-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barlow SM, Morrison PJ, Sullivan FM. Plasma corticosterone levels during pregnancy in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 1973;48(2):346P. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lépine S, Sulpice J-C, Giraud F. Signaling pathways involved in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of thymocytes. Crit Rev Immunol. 2005;25(4):263–288. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v25.i4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoffman-Goetz L, Fietsch CL. Lymphocyte apoptosis in ovariectomized mice given progesterone and voluntary exercise. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2002;42(4):481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gold SM, et al. Dynamic development of glucocorticoid resistance during autoimmune neuroinflammation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(8):E1402–E1410. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wüst S, et al. Peripheral T cells are the therapeutic targets of glucocorticoids in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;180(12):8434–8443. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schweingruber N, et al. Chemokine-mediated redirection of T cells constitutes a critical mechanism of glucocorticoid therapy in autoimmune CNS responses. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(5):713–729. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1248-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van den Brandt J, et al. Enhanced glucocorticoid receptor signaling in T cells impacts thymocyte apoptosis and adaptive immune responses. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(3):1041–1053. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andersen KG, Nissen JK, Betz AG. Comparative genomics reveals key gain-of-function events in Foxp3 during regulatory T cell evolution. Front Immunol. 2012;3:113. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sicotte NL, et al. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with the pregnancy hormone estriol. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(4):421–428. doi: 10.1002/ana.10301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pozzilli C, et al. Oral contraceptives combined with interferon β in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2(4):e120. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Voskuhl RR, et al. Estriol combined with glatiramer acetate for women with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(1):35–46. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lydon JP, et al. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1995;9(18):2266–2278. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]