Abstract

Serious infection is a recognized complication of intravenous drug abuse, and a major cause of morbidity and mortality in this patient population. Trends in rates and the associated cost of serious infections related to opioid abuse/dependence have not been previously investigated in the context of the US opioid use epidemic. Our study, using a nationally representative sample of U.S. inpatient hospitalizations, showed that hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence with associated serious infection both significantly increased from 2002 to 2012, respectively, from 301,707 to 520,275 and 3,421 to 6,535. Additionally, inpatient charges for both types of hospitalizations have almost quadrupled over the same time period, reaching totals of almost 15 billion for hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and more than 700 million for those related to associated infection in 2012. Medicaid was the most common primary payer for both types of hospitalizations. Our results characterize the financial burden on the healthcare system related to opioid abuse/dependence and one of the more serious downstream complications of this epidemic. These findings have important implications for the hospitals and government agencies that disproportionately shoulder these costs, and for clinicians, researchers, and policy makers interested in estimating the potential impact of targeted public health interventions on a national level.

Introduction

Opioid abuse and addiction have plagued the United States for decades. Mortality associated with opioid abuse increased dramatically beginning in the 1990s, with an almost doubling of the incidence of opioid poisoning deaths between 1999 and 2002.[1,2] Intimately linked to the abuse of opioid pain relievers is the recent increase in heroin use. Between 2003 and 2013, the number of people reporting heroin use in the past year approximately doubled from 314,000 to 681,000, and the rate of heroin poisoning deaths has quadrupled during the same time period from 2,080 to 8,257. Deaths attributable to opioids and heroin combined totaled 24,492 in 2013.[3,4] Furthermore, recent data indicate a shift from the exclusive use of prescription opioids to concurrent abuse of both heroin and prescription opioids–such that, almost half of patients with opioid dependence report abuse of both.[4–7]

Opioid abuse is associated with a number of potential downstream consequences, including serious infections related to intravenous administration, which can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The incidence and cost of these downstream infectious complications are relatively unexamined. Prior data suggest that the number of cases of infections associated with opioid use (for example, endocarditis and pyogenic spinal infections) has been on the rise, carrying with it substantial inpatient and long-term morbidity and mortality.[8–14] Unfortunately, the generalizability of existing studies examining opioid-related infections is limited by small sample sizes, select patient populations, and lack of nationally representative data.

In light of the shifting trends in prescription opioid and heroin abuse, we sought to define national trends in rates of inpatient hospitalizations involving serious infections in patients with opioid abuse/dependence and to estimate the associated morbidity, mortality, and costs, using a large, nationally representative data set.

Methods

Setting And Patients

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using discharge data from years 2002 and 2012 of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) developed for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This database is the largest publicly available, all-payer, national inpatient database in the United States, representing a 20% stratified sample of all inpatient hospitalizations.

Opioid Abuse/Dependence And Associated Infection

We used International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), discharge codes to define exposures of interest, including up to fifteen codes in any position (primary or secondary). “Opioid abuse/dependence” was defined as any ICD-9-CM code for abuse or dependence of opioids or heroin. “Opioid abuse/dependence with associated infection” was defined as any ICD-9-CM code for endocarditis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or epidural abscess in a patient with a code for opioid abuse/dependence during the same hospitalization.[15]

Statistical Analysis

All reported estimates reflect national estimates, generated using the approach recommended by the NIS to account for the sampling design of the database and accounting for the shift in sampling process between 2002 and 2012 to allow comparability of estimates (using the recommended weight variables). We estimated the total number of hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and those with associated infection overall and by primary payer. We also estimated the incidence of the selected infections among those hospitalizations with and without a diagnosis of opioid abuse/dependence.

We estimated total charges for inpatient services for hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and those with associated infection, with and without accounting for inflation using the Consumer Price Index inflation calculator provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.[16] To calculate the estimated total charges per hospitalization for each of these conditions, we divided the total estimated charges by the number of discharges.

Finally, as a measure of the functional impact and downstream burden on the health care system of hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and those with associated infection, we report disposition, categorized as: in-hospital death, home, facility (including skilled nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities, and other), left against medical advice, and other.

We used the z-test to compare numbers of hospitalizations and charges, and the chi-square test to compare proportions between 2002 and 2012. We used p value < 0.05 to define statistical significance for all comparisons.

All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.3.

Sensitivity Analyses

Because we were unable to assure that infections among patients with opioid abuse/dependence were attributable to the opioid use itself, we performed two sensitivity analyses wherein we recalculated our total hospitalization estimates after restricting our cohort to young patients without other strong risk factors for the infections of interest. First, we assessed the number of hospitalizations with endocarditis in those with opioid abuse/dependence in 2002 and 2012 after restricting our cohort to patients younger than age fifty, without congenital (present at birth) heart disease or preexisting mechanical valves, which represent inherent risks for endocarditis. In the second analysis, we assessed the number of hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence and any associated infection after restricting our cohort to patients younger than age fifty, without diabetes, which represents a risk for any infection.

Results

Total Number Of Hospitalizations

The number of hospitalizations nationally was almost identical in 2002 and 2012, as extrapolated from the NIS data, with an estimated 36,523,831 hospitalizations in 2002 and 36,484,846 in 2012.

Opioid Abuse/Dependence And Associated Infection

The number of hospitalizations with a diagnosis of opioid abuse/dependence and the number of hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence with an associated infection significantly increased between 2002 and 2012 (Exhibit 1). These same trends were reflected for each of the individually specified infections–endocarditis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and epidural abscess–with 1.5, 2.2, 2.7, and 2.6 fold increases, respectively. Because total hospitalizations stayed relatively constant between 2002 and 2012, standardizing estimates per 100,000 hospitalizations yielded the same relative increases between 2002 and 2012. See Appendix Exhibit B1 for standard errors associated with these estimates.[15]

Exhibit 1.

National estimates of hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated infections, 2002 and 2012

| 2002 (N = 36,523,831) |

2012a (N = 36,484,846) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Number | Number | |

| Opioid abuse/dependence | 301,707 | 520,275**** |

| Opioid abuse/dependence with infectionb | 3,421 | 6,535**** |

| Endocarditis | 2,077 | 3,035*** |

| Osteomyelitis | 458 | 985**** |

| Septic arthritis | 729 | 1,940**** |

| Epidural abscess | 411 | 1,085**** |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Inpatient Sample, 2002 and 2012.

Differences compared to 2002 were assessed using the z-test.

This row represents the number of hospitalizations with at least one of the specified infections (endocarditis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or epidural abscess).

p< 0.01

p < 0.001

The number of hospitalizations with any of the selected infections among discharges with opioid abuse/dependence was 3,421 out of 301,707 (1.1%) in 2002 and 6,535 out of 520,275 (1.3%) in 2012. The number of hospitalizations with any of the selected infections among discharges without opioid abuse/dependence was 121,776 out of 36,222,124 (0.3%) in 2002 and 166,405 out of 35,964,571 (0.5%) in 2012 (data not shown), demonstrating that the selected infections occur at an increased rate in the cohort with a concurrent opioid abuse/dependence diagnosis.

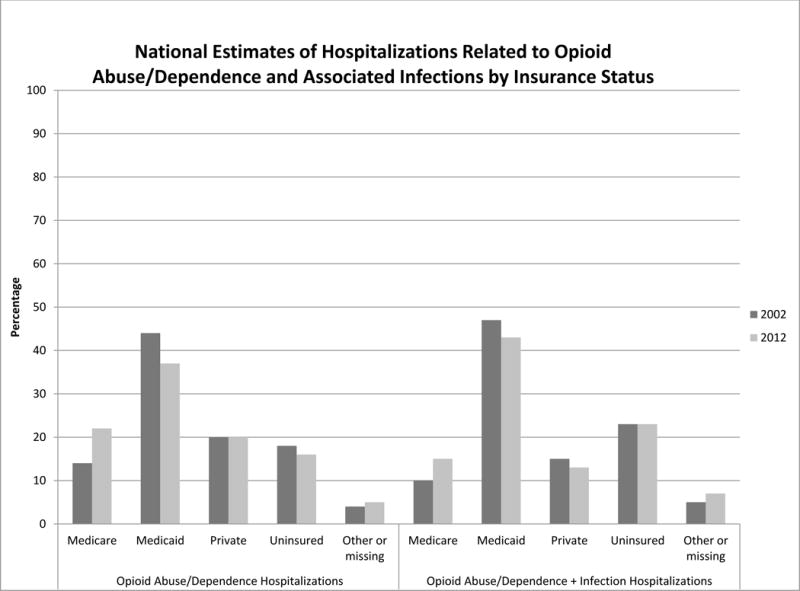

Payer Distribution

The primary payer distribution in 2002 for both hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence and hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence with associated infection was similar to the payer distribution in 2012 (Exhibit 2). The most common primary payer in 2002 and 2012 for both groups was Medicaid. Compared to hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence overall, hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence with associated infection were more likely to be uninsured in both 2002 and 2012. See Appendix Exhibit B2 for numeric estimates and standard errors related to insurance demographics.[15]

EXHIBIT 2.

National estimates of hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated infections by insurance status, 2002 and 2012

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Inpatient Sample, 2002 and 2012.

**** p < 0.001

Total Charges

Total inpatient charges for hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence more than tripled between 2002 and 2012 ($4,574,263,003 and $14,850,435,892, respectively, p < 0.001) (Exhibit 3), and the increase remains significant after accounting for inflation ($11,636,166,781 in 2012 represented in 2002 dollars, p < 0.001). Total inpatient charges for hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence with associated infection also more than tripled between 2002 and 2012 ($190,678,889 and $700,663,008, respectively, p < 0.001), and the increase remains significant after accounting for inflation ($549,009,450 in 2012 represented in 2002 dollars, p < 0.001). In 2012 the estimated total charge per hospitalization related to opioid abuse/dependence was $28,543, and opioid abuse/dependence with associated infection was $107,217. See Appendix Exhibit B3 for standard errors associated with these estimates.[15]

Exhibit 3.

National estimates of total charges and disposition for hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated infections, 2002 and 2012

| 2002 | 2012a | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence | 301,707 | 520,275 |

| Length of stay in days (mean) | 5.8 | 5.2 |

| Number of procedures (mean) | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Total charges | $4,574,263,003 | $14,850,435,892 |

| Disposition (percent of total discharges with opioid abuse/dependence) | ||

| In-hospital death | 1% | 1% |

| Home | 75 | 79 |

| Facilityb | 9 | 10 |

| Left against medical advice | 13 | 8 |

| Other or missing | 2 | 2 |

| Number of hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence with infectionc | 3,421 | 6,535 |

| Length of stay in days (mean) | 16.8 | 14.6 |

| Number of procedures (mean) | 3.1 | 3.3 |

| Total charges | $190,678,889 | $700,663,008 |

| Disposition (percent of total discharges with opioid abuse/dependence with infection) | ||

| In-hospital death | 5% | 3% |

| Home | 49 | 49 |

| Facilityb | 26 | 27 |

| Left against medical advice | 11 | 12 |

| Other or missing | 8 | 9 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Inpatient Sample, 2002 and 2012.

Total charges for 2012 are not adjusted for inflation.

Any facility other than another hospital; includes skilled nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities, and others.

Since each hospitalization can include multiple infections, this row represents the number of hospitalizations with at least one of the specified infections (endocarditis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or epidural abscess).

Disposition

The distribution of disposition status in 2002 for both hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence overall and hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence with associated infection was similar to the distribution of disposition status in 2012 (Exhibit 3). Although the most common disposition in 2002 and 2012 was to be sent home for both groups, hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence with associated infection were more likely to die during hospitalization, less likely to be sent home, and more likely to be discharged to a second medical facility compared to hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence overall, in both 2002 and 2012 (p < 0.001 for each comparison). See Appendix Exhibit B3 for numeric estimates and associated standard errors related to disposition status.[15]

Sensitivity Analyses

Among patients under age 50, without congenital heart disease or preexisting mechanical heart valves, the number of hospitalizations with endocarditis among hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence was 1,712 out of 244,147 (0.7%) in 2002 and 2,345 out of 347,390 (0.7%) in 2012, while these numbers among hospitalizations without opioid abuse/dependence were 6,689 out of 17,487,508 (0.04%) in 2002 and 8,470 out of 15,928,790 (0.05%) in 2012. In this subpopulation without underlying risk factors for endocarditis, there was a 1.4 fold increase in the number of hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence and a concurrent diagnosis of endocarditis between 2002 and 2012 (1,712 in 2002 and 2,345 in 2012, p < 0.001), virtually identical to that seen in the overall cohort.

Among patients under age 50, without diabetes, the number of hospitalizations with any infection among hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence was 2,594 out of 230,474 (1.1%) in 2002 and 4,220 out of 318,995 (1.3%) in 2012, while these numbers among hospitalizations without opioid abuse/dependence were 30,027 out of 16,769,678 (0.2%) in 2002 and 33,955 out of 14,928,754 (0.2%) in 2012. In this subpopulation without one of the most prevalent risk factors for infection, there was a 1.6 fold increase in the number of hospitalizations with opioid abuse/dependence and a concurrent diagnosis of infection between 2002 and 2012 (2,594 in 2002 and 4,220 in 2012, p < 0.001), again almost identical to that seen in the overall cohort.

Discussion

In this large, national cohort of inpatient hospitalizations, we found that both hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence with associated serious infection have significantly increased from 2002 to 2012. Inpatient total charge estimates have almost quadrupled for both types of hospitalizations during the same time interval, reaching totals of almost $15 billion for hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and more than $700 million for hospitalizations related to associated infection in 2012. The primary payer for hospitalizations related to both of these conditions is Medicaid. Compared to discharges related to opioid abuse/dependence overall, discharges related to opioid abuse/dependence with infection where almost four times more costly per hospitalization, more likely to be uninsured, more likely to die during hospitalization, and more likely to require placement in a second facility after discharge. Our study provides new data on the incidence, cost, and outcomes of serious infections related to opioid abuse/dependence, demonstrating the increasing magnitude of the downstream complications associated with this epidemic.

Our finding that hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence are on the rise nationally since 2002 is consistent with prior research that has evaluated the incidence of emergency department visits for nonmedical use of opioids, the rise in accidental deaths as a result of opioid overdose, and the increase in people using opioids and heroin illicitly.[2,17] Prior studies conducted using the same data source demonstrated similar hospitalization trends; however, those authors included nonspecific codes for “psychodysleptics” and “hallucinogens” in their analysis and did not investigate the incidence of infections among patients with opioid abuse/dependence.[4,18] Other studies have investigated infectious complications specifically; however, these were all small, single-center studies, mostly focusing on surgical patient populations.[8–14] To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the rates, costs, and outcomes of hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence with associated infection in a national sample.

Although we are unable to definitively attribute these serious infections to opioid abuse/dependence, there are several aspects that support such an attribution. First, the incidence of the selected infections in those with opioid abuse/dependence was more than double the incidence found among hospitalizations without opioid abuse/dependence. Second, the relative increase in incidence of opioid abuse/dependence with endocarditis that we observed between 2002 and 2012 was almost identical when focusing specifically on endocarditis in younger patients without other reasons for developing endocarditis, such as congenital heart disease or preexisting mechanical valves. The same was true when examining the incidence of any infection among those with opioid abuse/dependence who were young and without diabetes. Finally, the infections we chose all commonly require spread through the bloodstream, and in a patient with opioid abuse/dependence presenting with endocarditis, for example, it is reasonable and common practice to assume that the endocarditis is secondary to intravenous drug abuse.

Total charges for hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated infections have increased out of proportion to the rate of increase in number of hospitalizations for these conditions over the same time period, even after accounting for inflation. We are unable to determine the underlying cause in the present analysis, but it is likely multifactorial. Possibilities include increasing costs for the same care, greater resource use, and a higher severity of illness. That length of hospitalization declined over the time interval and number of procedures remained relatively constant argue against increased severity of illness or resource use as explanations. Future research should investigate the factors underlying the exponentially rising charges.

The total charges presented in this analysis reflect only inpatient charges and do not include the cost of post-discharge care, which is likely to be substantial, particularly in patients with infection. The psychosocial aspects of addiction complicate prolonged treatment courses of intravenous antibiotics in this patient population. Concerns over the ability to complete the treatment course independently and adherence to proper care instructions and use of indwelling intravenous catheters often require the completion of treatment in a monitored setting. Indeed, a larger proportion of those with a serious infection required further care in a skilled nursing facility when compared to those with opioid abuse/dependence overall. Additionally, those patients with serious infections who were discharged home likely incurred significant costs from home care based on the need for long courses of antibiotics and visiting nursing services. As such, the total cost to the health care system is substantially greater than the already staggering hospitalization charges demonstrated in this analysis.

Additionally, our results demonstrate that the financial burden largely falls on government-funded agencies, patients, and hospitals because only 20% of discharges related to opioid abuse/dependence and 14% of discharges with associated infection were covered by private insurance. The high rate of uninsured status, particularly among those with associated infection (23% uninsured) could have implications for the care of these individuals. For example, patients with complex histories (medically and psychosocially) are often declined care at skilled nursing facilities, which leads to a longer inpatient stay and higher costs for those hospitalizations. These high costs in the face of a high rate of uninsured status create perverse incentives wherein hospitals and care organizations may seek to transfer these patients to other health care systems or hospitals. The potential lack of “ownership” of the patient’s care may exacerbate the already troubling issues related to access to care and follow through on follow-up care demonstrated by others.[14]

Although our study was large and nationally representative, there were a number of important limitations. First, our reliance on ICD-9-CM coding and individual physicians and coders to capture all hospitalizations for patients with these co-occurring conditions could have led to underestimation of the magnitude of our estimates or bias in the event of different coding practices in 2002 compared to 2012. Additionally, the activity status of a patient’s drug abuse was unknown. Furthermore, our inability to separate out intravenous from other routes of administration limited our ability to attribute infectious complications directly to opioid abuse. However, recent studies demonstrate significant interchangeability of prescription opioid and heroin abuse.[4–7] Additionally, since we used the same definition across years, comparisons across years should not be affected. Finally, our analyses did not account for demographic shifts in patients with opioid abuse/dependence between 2002 and 2012, which could have affected cost and disposition estimates.

In conclusion, the rates of hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated infection are on the rise nationally. The rise in associated inpatient charges is outpacing the increase in number of hospitalizations and places a significant financial burden on the health care system as a whole. Downstream consequences of opioid abuse/dependence, such as related infections, are particularly costly, and a continued focus on decreasing access to opioids, early treatment, and preventive strategies is necessary to decrease the burden of disease and cost to the health care system and society.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Shoshana Herzig was funded by Grant No. K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). The funding organization had no involvement in any aspect of the study, including design, conduct, and reporting. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the Veterans Health Administration, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, or the NIA.

Contributor Information

Matthew V. Ronan, Clinical Faculty, VHA Boston Healthcare System, West Roxbury Medical Center; Instructor in Medicine Harvard Medical School, Adjunct Instructor in Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine.

Shoshana J. Herzig, Division of General Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; Assistant Professor in Medicine, Harvard Medical School.

References

- 1.Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(21):1981–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(9):618–27. doi: 10.1002/pds.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2014. Sep, (Department of Health and Human Services Publication No. 14-4863). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unick GJ, Rosenblum D, Mars S, Ciccarone D. Intertwined epidemics: national demographic trends in hospitalizations for heroin- and opioid-related overdoses, 1993–2009. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(7):821–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones CM, Logan J, Gladden RM, Bohm MK. Vital signs: demographic and substance use trends among heroin users–United States, 2002–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(26):719–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Harney J. Shifting patterns of prescription opioid and heroin abuse in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1789–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1505541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabell CH, Jollis JG, Peterson GE, Corey GR, Anderson DJ, Sexton DJ, et al. Changing patient characteristics and the effect on mortality in endocarditis. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(1):90–4. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferro JM, Fonseca AC. Infective endocarditis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:75–91. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-7020-4086-3.00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadjipavlou AG, Mader JT, Necessary JT, Muffoletto AJ. Hematogenous pyogenic spinal infections and their surgical management. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(13):1668–79. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pant S, Patel NJ, Deshmukh A, Golwala H, Patel N, Badheka A, et al. Trends in infective endocarditis incidence, microbiology, and valve replacement in the United States from 2000 to 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2070–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slipczuk L, Codolosa JN, Davila CD, Romero-Corral A, Yun J, Pressman GS, et al. Infective endocarditis epidemiology over five decades: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Lenehan B, Itshayek E, Boyd M, Dvorak M, Fisher C, et al. Primary pyogenic infection of the spine in intravenous drug users: a prospective observational study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37(8):685–92. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31823b01b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziu M, Dengler B, Cordell D, Bartanusz V. Diagnosis and management of primary pyogenic spinal infections in intravenous recreational drug users. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37(2):E3. doi: 10.3171/2014.6.FOCUS14148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 16.Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI inflation calculator [Internet] Washington (DC): Department of Labor, BLS; [cited 2016 Mar 17]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedegaard H, Chen LH, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin: United States, 2000–2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(190):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owens PL, Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Washington RE, Kronick R. Hospital inpatient utilization related to opioid overuse among adults, 1993–2012. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Aug, (Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Brief No. 177). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.