A key determinant for the survival of an organism is the ability to recognize and respond to invading pathogens without damaging host tissues. This is largely accomplished by the concerted activity of the innate and adaptive branches of the immune system that efficiently eliminate invading pathogens and restore tissue homeostasis. An initial step in the generation of robust immune responses is the recognition of pathogens by host cells, triggering subsequent immune cell activation and induction of pro-inflammatory responses. This initial recognition is facilitated via pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that represent highly-conserved molecular structures uniquely found in bacterial, viral and fungal pathogens, but not in host tissues. Such structures include peptidoglycans, zymosan, lipopolysaccharides, flagellin, double-stranded and single-stranded RNA, and CpG-containing DNA (1). So far, an ever-increasing number of receptors with the capacity to sense and respond to these PAMPs have been identified and are broadly categorized into distinct receptor families: Toll-like receptors (TLR), RIG-1 (retinoic acid-inducible gene I)-like receptors (RLR), NOD-like receptors, and C-type lectin receptors (2–4). Following engagement, these pattern-recognition receptors trigger the activation of several inflammatory pathways essential to mediate robust anti-microbial activity and induce sustained immune responses. This central role in immunity for pathogen sensing by innate immune receptors is also reflected by the emergence of pattern-recognition receptor early in evolutionary history, as evidenced by the presence of highly-conserved gene orthologues in invertebrate species. Additionally, genetic analysis of human TLR and NOD genes provided evidence for strong positive selection pressure in human populations, and several non-synonymous polymorphisms influencing receptor activity have been associated with disease susceptibility (1).

Despite the key role for innate immune receptors in mediating pathogen recognition and responses by effector leukocytes, they present limited capacity to recognize pathogens of infinite diversity. Another key mechanism for recognition and clearance of non-self material is accomplished by IgG antibodies, which provide specific recognition of antigens of almost unlimited diversity. Indeed, through the diversification of their variable domains (VH and VL), antibodies have the capacity to specifically recognize diverse antigens, providing effective host protection during an immune response. Contrary to the antigen-binding Fab domain that exhibits astonishing variability, antibodies also comprise a relatively constant domain, the Fc domain. Recognition and binding of antibodies to the surface of the leukocytes is mediated through interactions of their Fc domains with specialized receptors, Fc receptors, expressed by several types of circulating and tissue-resident leukocytes (5). By directly linking molecules of the adaptive immunity with innate leukocytes, Fc receptors represent an important component that links both branches of immunity, enabling innate immune cells to specifically recognize and respond to antigens of unlimited diversity.

While traditionally termed the ‘constant domain/region’ of the antibody molecule, the Fc domain is, in fact, heterogeneous in both primary amino acid sequence (IgG subclass), and in the composition of the Fc-associated glycan (5–7). These two determinants regulate the structure and conformational flexibility of the IgG Fc domain and, in turn, determine interactions with various Type I and Type II Fc receptors (FcγR). Indeed, recent crystallographic studies support the existence of two main conformational states for the Fc domain: an “open” and a “closed” that are determined by the Fc-associated glycan structure; a highly conserved glycan site present in all human IgG subclasses and among many mammalian species (8, 9). In view of the two conformational states of the Fc domain, FcγRs can be categorized into type I and type II receptors, based on their capacity to interact with the “open” or the “closed” Fc domain conformation, respectively (8, 9). Engagement of type I and type II FcγR by the Fc domain is a tightly regulated process that is primarily determined by the conformational flexibility of the Fc domain and results in the induction of pleiotropic activities by effector leukocytes (5, 10).

IgG Fc domain heterogeneity and structural flexibility

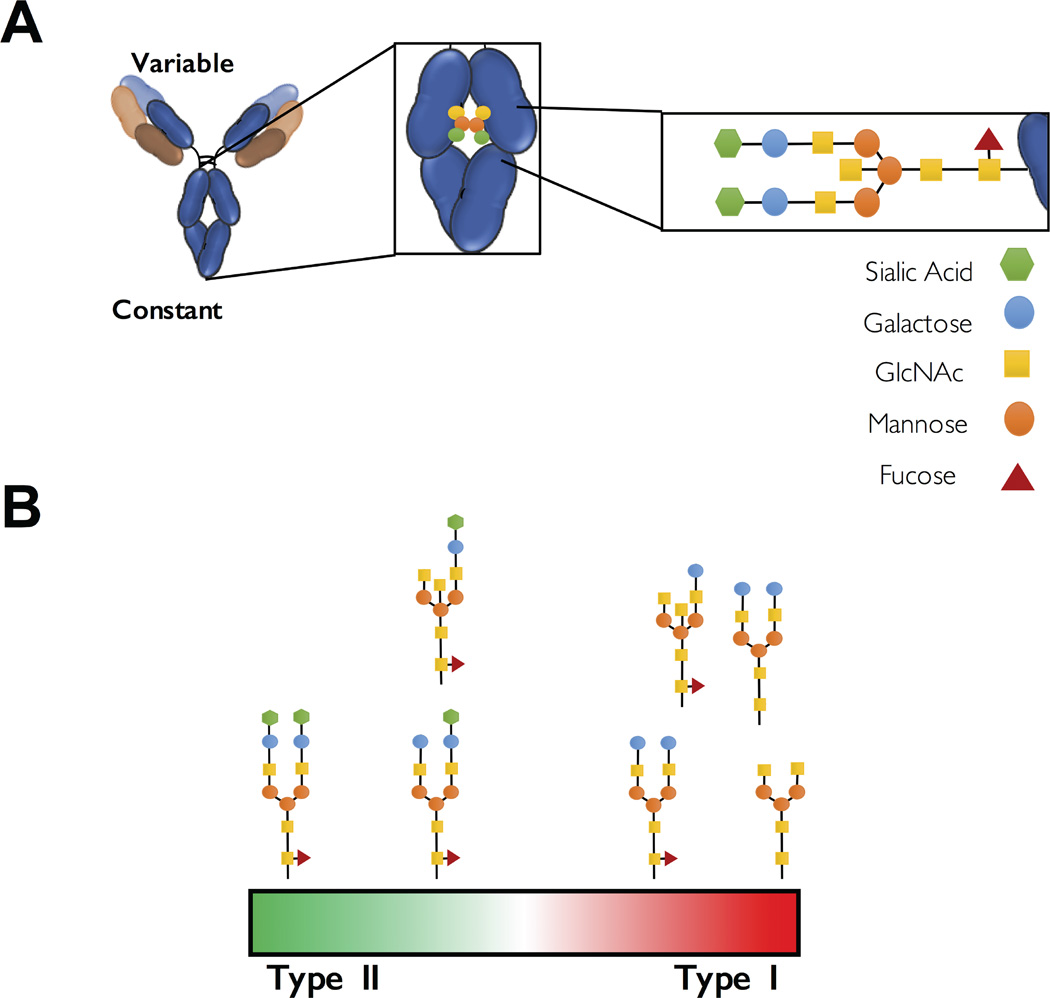

The highly flexible structure of the Fc region is indicative of the unique structural organization of its different domains. In particular, the Fc region is composed of the two constant domains (CH2 and CH3) of the two heavy chains that form homodimers through tight association of the two CH3 domains at the C-terminal proximal region of the IgG as well as the presence of disulfide bonds in the CH2-proximal hinge region (11). This results in a characteristic horseshoe-like conformation, with the two CH2 domains forming a hydrophobic cleft, where the central N-linked glycan structure is localized. This Fc-associated glycan is conjugated to the amino acid backbone of the CH2 domain at position Asn297 and is required to maintain the Fc domain in a structural conformation permissive for interactions with FcγRs (12, 13)(Figure 1A). Indeed, genetic deletion of the Asn297 site or enzymatic removal of the Fc-associated glycan abrogates the capacity of the Fc domain to interact with FcγRs (14–17). In addition, an ever-increasing body of evidence strongly suggests a crucial role for the Fc-associated glycan in the regulation of Fc domain interactions with type I and type II FcγRs through modulation of the Fc domain flexibility (15, 16).

Figure 1. Structure and composition of the Fc-associated N-linked glycan regulates binding to type I and type II FcγRs.

(A) An N-linked glycan structure is attached at the CH2 domain of each of the two heavy chains of IgG and consists of a core heptasaccharide structure that is composed of fucose, galactose, N-acetylglucosamine and sialic acid residues. (B) The structure and composition of this Fc-associated glycan determine binding specificity and affinity of the IgG Fc domain for different types of FcγRs. Several glycoform combinations exist with distinct binding capacity to interact with type I and type II FcγRs.

The Fc-associated glycan structure consists of a core heptasaccharide structure that is attached to the CH2 domains of each of the two heavy chains that comprise the Fc domain (12, 15)(Figure 1A). Previous analyses of the Fc glycan composition revealed substantial heterogeneity at steady-state conditions, due to the selective addition of fucose, galactose, N-acetylglucosamine and sialic acid residues to the core glycan structure (5, 6, 18). Such heterogeneity in the glycan structure and composition finely tunes the affinity of the Fc domain for binding to the different classes of type I and type II FcγRs (6, 14, 19)(Figure 1B). For example, the branching fucose residue regulates the Fc domain affinity specifically for the activating type I FcγR, FcγRIIIa, without any impact on the capacity of the Fc domain to interact with other classes of type I FcγRs (20, 21). Based on the selectively enhanced binding affinity for FcγRIIIa, Fc glycoengineering has been successfully used as a strategy to generate antibodies with improved in vivo efficacy, as afucolylated IgG glycovariants exhibited enhanced Fc effector activity compared to their fucosylated counterparts (22–26).

In contrast, the presence of terminal sialic acid residues is associated with reduced binding to type I FcγRs and preferential engagement of type II FcγRs (18, 27, 28); an effect attributed to the induction of a conformational change of the CH2 domains upon sialylation that affects type I and type II FcγR binding (5, 8, 9). Indeed, sialylation of the Fc-associated glycan exposes a region at the CH2–CH3 interface, which serves as the binding site for type II FcγRs (8, 9). This conformational change also results in the obstruction of the type I FcγR binding site at the hinge-proximal region of the CH2 domain, suggesting that Fc domain glycosylation modulates the capacity of the Fc domain to adopt two mutually exclusive conformations: an ‘open’ that enables for type I, but not type II FcγR binding, and a ‘closed’ that is induced upon sialylation and preferentially engages type II, but not type I FcγRs (9).

FcγRs: types, function and downstream signaling

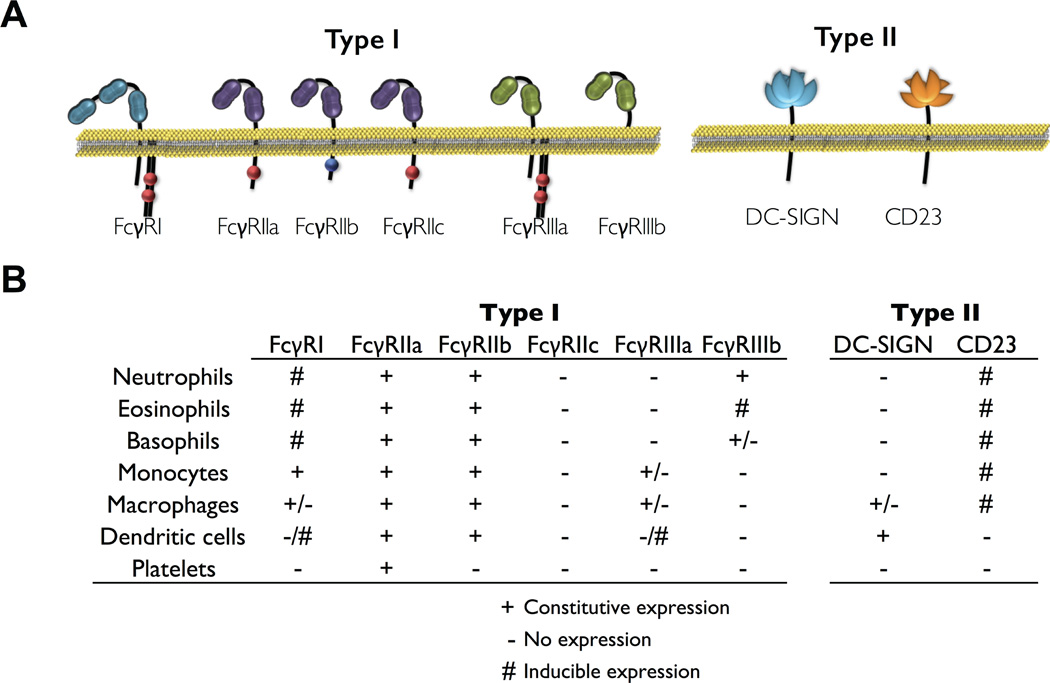

The conformational state of the Fc domain regulates the interactions with two distinct types of FcγRs: type I and type II that differ in terms of their structural domain organization as well as the stoichiometry by which they interact with the Fc domain (Figure 2A). Type I FcγRs belong to the immunoglobulin (Ig) receptor superfamily and their extracellular, IgG binding region consists of two or three Ig-like domains (29, 30). Type I FcγRs-Fc interactions are mediated through 1:1 binding of the FcγR loop region between the Ig-like domains with the hinge-proximal CH2 domain of the IgG Fc (31–33). In contrast, all type II FcγRs are members of the C-type lectin receptors and recognize the Fc domain only at the closed conformation at a 2:1 (Fc:FcγR) stoichiometry through interactions with the CH2–CH3 domain interface that is exposed following acquisition of the closed conformation state induced upon sialylation (5, 8, 9).

Figure 2. Overview of type I and type II FcγR structure and expression pattern in myeloid cell populations.

(A) Structural characteristics of type I and type II FcγRs. Type I FcγRs belong to the immunoglobulin receptor superfamily and are composed of two or three extracellular Ig-like domains that interact with the IgG Fc domain at the hinge proximal region of the CH2 domain. Type II FcγRs comprise DC-SIGN and CD23, both C-type lectin receptors, that bind sialylated Fc IgGs. (B) Expression pattern of type I and type II FcγRs in myeloid leukocyte populations. The expression of several FcγRs is determined by cell differentiation status and is regulated by cytokines, like IL-4 and IFNγ.

In humans, type I FcγRs are encoded by eight different genes, each with multiple transcriptional isoforms, located at a locus on the long arm of chromosome 1 (1q21–23). Genetic analysis suggested that the majority of the FcγR genes (with the exception of the genes encoding FcγRI) emerged throughout the evolutionary history through sequential gene duplication events of the ancestral FcγR gene locus, giving rise to the unique organization of the human IgG locus, which comprises several FcγR genes that share high degree of homology (34, 35). Type I FcγRs are further sub-divided into high and low affinity receptors, based on their capacity to interact with monomeric or multimeric IgG, respectively. FcγRI represents the high affinity FcγR and is capable of interacting with momoneric IgG with relatively high affinity (Kd:10−9 – 10−10 M). Three genes coding for FcγRI have been described: FCGR1A, FCGR1B, and FCGR1C; however, only FCGR1A encodes the prototypic high affinity receptor, FcγRI that is capable of high affinity IgG binding (36). FCGR1B and FCGR1C possibly represent pseudogenes that arose from duplication of the FCGR1A gene and express truncated or soluble forms of FcγRI, with unknown or poorly characterized function (36, 37). In particular, the FcγRIb1 and FcγRIc transcripts contain premature stop codons within the extracellular domain of FcγRI, possibly representing soluble forms of the FcγRI receptor (36, 37). In contrast, the FcγRIb2 isoform is expressed as an intracellular protein, retained predominantly within the endoplasmic reticulum; however, its function remains unknown (37, 38). The increased affinity of FcγRI for IgG is attributed to its unique structure, as contrary to the low affinity FcγRs (like FcγRII and FcγRIII), the α ligand-binding chain of FcγRI comprises three V-type, Ig-like domains that greatly stabilize Fc-FcγR interactions (39). The FcγRI α chain associates with a disulfide-bonded dimer of the Fc receptor γ chain (encoded by FCER1G), a signal transducing polypeptide initially described as a component of the high affinity IgE receptor FcεRI (40–42). Association of the FcγRI α chain with the FcR γ chain is necessary for receptor expression and signaling following receptor engagement (41, 43). Indeed, the FcR γ chain carries activating signaling motifs (ITAM – immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif), which serves as the docking site for Syk family kinases and mediates signal transduction following IgG-FcγRI interactions (40, 44). FcγRI is constitutively expressed by monocytes and macrophages, as well as by many myeloid progenitor cells. FcγRI expression can also be induced in other myeloid cell types, like neutrophils and eosinophils, following stimulation with primarily interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and to a lesser extent by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), interferon-α and interleukin-12 (45, 46)(Figure 2B).

Apart from the high affinity FcγRI, FcγRs (like FcγRII and FcγRIII) display low affinity for monomeric IgG. Instead of engaging monomeric IgG, low affinity FcγRs are only capable of binding to aggregated IgG through multiple multivalent, low affinity, high avidity interactions (33). This is particularly important, as low affinity FcγRs can be engaged only by antibody-antigen complexes during an immune response, but not at steady state conditions by monomeric IgG in the absence of antigen. This ensures that engagement and crosslinking of low affinity FcγR occurs only during an immune response, preventing thereby inappropriate or excessive FcγR-mediated signaling at physiological conditions. All genes encoding the low affinity FcγRs are clustered into a single FcγR locus, located at chromosome 1 and represent a series of multiple gene duplication and recombination events, followed by gain-of-function mutations of the ancestral FcγR locus, which can be traced back early in mammalian evolution as well as in marsupials (35). In humans, five low affinity FcγRs have been described, along with several genetic variants (either in the form of non-synonymous substitutions and copy number variants) that impact FcγR expression and ligand binding affinity, influencing thereby disease susceptibility and severity for a number of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune pathologies (29). A common feature of all low affinity FcγRs is the presence of two V-type, Ig-like domains that comprise the extracellular, ligand binding region (Figure 2A). A series of crystallographic, molecular modeling and mutational analyses have previously identified the ligand binding interface for each low affinity FcγR, indicating that the IgG binding region is localized in the second, membrane-proximal Ig-like domain, which is normally accessible for IgG interactions due to the horizontal orientation of the extracellular domain of the receptor (31–33, 47–50).

Despite the similarities between the low affinity FcγRs in relation to their extracellular domains and binding interface, each FcγR exhibits unique characteristics in terms of their intracellular structure and signaling activities. FcγRIIa, FcγRIIb, and FcγRIIc (encoded by FCGR2A, FCGR2B, and FCGR2C, respectively) share a characteristic structure, which is the presence of functional signaling motifs in their intracellular domains. FcγRIIa, b, and c are expressed as a single chain (α chain) membrane receptors that comprised both the extracellular, IgG-binding region, as well as an intracellular signaling domain, without requiring association with the FcR γ chain for signaling or expression (30). The intracellular motifs of FcγRII include either an ITAM (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motif) for FcγRIIa and FcγRIIc or an ITIM (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif) for FcγRIIb (10). FcγRIIa is expressed by diverse cell types, including predominantly cells of myeloid origin, like polymorphonuclear leukocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, monocytes, and platelets (10). Additionally, FcγRIIa expression has been reported in certain types of endothelial and epithelial cells, as well as in subsets of memory T cells (memory α/β T cells). FcγRIIb, the sole FcγR capable of transducing inhibitory signals upon crosslinking, exhibits two main splicing isoforms: b1 and b2. FcγRIIb1 represents the full-length transcript, which encodes a signal sequence that inhibits receptor internalization (51–54). In contrast, FcγRIIb2 is generated by skipping the exon that codes for this signal sequence, resulting in a variant that is capable of receptor internalization following IgG crosslinking (55). In addition to the differential internalization capacity, FcγRIIb1 and FcγRIIb2 also exhibit characteristic expression patterns. More specifically, FcγRIIb1, the full-length variant that is incapable for internalization, is predominantly expressed by cells of the lymphoid lineage, like B cells, whereas FcγRIIb2 expression is restricted to phagocytic, myeloid cells, like monocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, and eosinophils (52)(Figure 2B). FcγRIIc is encoded by the FCGR2C gene and shares high degree of similarity with both FcγRIIa and FcγRIIb, probably reflecting a gene recombination event between FCGR2A and FCGR2B late in human evolution (35). Indeed, FcγRIIc represents a chimeric receptor comprising the extracellular, ligand binding region of FcγRIIb and the intracellular, ITAM-containing domain of FcγRIIa. Its expression is mainly restricted to NK cells (56); however, for the majority of human populations (70–90%), FcγRIIc expression is absent due to the presence of a premature stop codon at exon 3 (56, 57).

Similar to FcγRII receptors, FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIIb are characterized by relatively high sequence similarity, indicating a common origin for FCGR3A and FCGR3B genes, which encode FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIIb, respectively. Indeed, previous genetic analyses and comparison of the FcγR locus among the various primate species revealed that the FCGR3B gene emerged relatively late in evolutionary history as a result of gene duplication of FCGR3A followed by a point mutation at the extracellular, membrane-proximal region of the receptor (35, 58). This key point mutation created a glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor signal sequence, resulting in the processing of FcγRIIIb, as a GPI-anchored protein (59). This difference accounts for the distinct structural differences between FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIIb (Figure 2A). Whereas FcγRIIIa is a transmembrane protein that requires the association with the FcR γ chain for expression and signaling (44, 60), FcγRIIIb is post-translationally processed as GPI-anchored protein lacking intracellular signaling domains (61). This difference also influences the receptor immunostimulatory activity following engagement. In contrast to FcγRIIIa, which is capable of transducing potent activating signals following receptor crosslinking through the FcR γ chain, FcγRIIIb lacks robust signaling capacity (59, 62). FcγRIIIb often relies on other receptors (like FcγRIIa) or accessory chains (like ζ chain or FcR γ chain) for signaling activity (42). The differences between FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIIb are not limited to their structure and signaling activity, but also extend to their expression pattern and distribution. FcγRIIIb expression is restricted to neutrophils, which constitutively express high levels of FcγRIIIb on their surface (61, 63). Other granulocyte subsets, like eosinophils also express FcγRIIIb, but only following induction with IFN-γ (5, 64). In contrast, FcγRIIIa expression is widely expressed by several leukocyte cell types, including macrophages, NK cells, and a subset of monocytes (CD14int, CD16high); patrolling monocytes) (5, 10, 65)(Figure 2B). FcγRIIIa expression levels are also greatly variable among the different tissue-resident macrophage and dendritic cell subsets (10).

Since almost all FcγRs are capable of transducing intracellular signals following crosslinking by IgG complexes, FcγRs are often divided into activating or inhibitory, based on their ability to transduce immunostimulatory or inhibitory signals (16). Common to all myeloid cell types is the concurrent expression of both activating and inhibitory FcγRs on their surface with competing signaling activity. Differential engagement of activating or inhibitory FcγRs could therefore influence the outcome of IgG-mediated inflammation; a concept that has been experimentally evaluated in several in vivo models of antibody-mediated cellular cytotoxicity (16, 64, 66, 67). Activating FcγRs have the capacity to initiate a range of cellular activation processes through their activating signaling motifs (ITAMs), in processes resembling those described for other antigen receptors, like the T and B cell receptors (68). Most Fc receptors consists of heterodimers of the α subunit, which constitutes the ligand-binding domain, along with the FcR γ chain (either one or two) that contains the ITAM motifs necessary for signaling (40, 61, 69)(Figure 2A). FcR γ chain (encoded by FCER1G) is structurally and functionally related to the ζ chain of the T cell receptor and are both located at the same locus on chromosome 1. FcR γ chain normally forms γ-γ homodimers that associate with the α subunit through transmembrane domain interactions of an aspartic acid residue of the γ chain with basic residues of the α subunit (51, 70). Apart from γ-γ homodimers, heterodimers between the FcR γ chain and ζ chain have been reported to associate with the FcR α subunit in vitro; however, it is unclear whether this association occurs naturally (71).

In contrast to the FcγRs that require the association with the FcR γ chain for expression and signaling, FcγRIIa and FcγRIIc comprise only a single α subunit that not only has the capacity to interact with the Fc domain of IgG, but also possesses an ITAM signaling motif within its intracellular domain. These receptors, which are uniquely found in humans, have the capacity to transduce activating signals following receptor crosslinking, in a process similar to FcγRs that require association with the FcR γ chain, like FcγRIIIa. Several biochemical and biophysical studies have elucidated the precise signaling pathways that are activated following binding of IgG complexes to activating FcγRs (10, 72). Since signaling of activating FcγRs is mediated through motifs (ITAM) or accessory signaling proteins (like the FcR γ chain) that are also found in the high affinity IgE receptor, FcεRI, both Fcγ and Fcε receptors share a number of common features related to their signaling activity following receptor crosslinking. Indeed, initial studies on the high affinity FcεRI receptor have provided useful insights into the mechanisms by which activating FcγRs transduce intracellular signals (73–75). Apart from the difference in their capacity to interact with monomeric IgGs, high and low affinity FcγRs also differ in relation to the sequence of events that are required for the initiation of downstream signaling. For example, high affinity receptors require binding of monomeric antibodies that are subsequently aggregated through the recognition and binding of multivalent antigens to their Fab domains (73, 75). In contrast, low affinity FcγRs can only engage antibody-antigen complexes, but not monomeric antibodies. Binding of such complexes is accomplished through multiple low affinity, high avidity interactions that facilitate receptor clustering and subsequent initiation of intrinsic signals (76, 77). Despite the differences between high and low affinity FcγRs in the events preceding receptor crosslinking, all activating FcγRs share a common pattern of signal cascade activation following crosslinking. In particular, upon receptor aggregation, two or more ITAM domains present in the FcR γ chain or in the intracellular region of the α subunit of FcγRIIa and FcγRIIc become cross-phosphorylated by Src and Syk family kinases, including Lyn, Lck, Hck, and Fgr (62, 78–83). In addition to these kinases, phosphorylation of additional proteins including FAK, ZAP-70 and ζ chain subunits have been reported following receptor aggregation (81, 83, 84). Initial activation of Syk and Src family kinases is accompanied by subsequent activation of downstream signaling pathways, including the activation of phospholipase C γ (PLCγ), which in turn generates metabolites that lead to the activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and inositol triphosphate (IP3), triggering a rapid increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels through mobilization of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pool (85, 86). Elevated intracellular Ca2+ levels also activate a number of Ca2+-regulated signaling proteins, including PKC (87, 88). Finally, a number of late signaling pathways become activated following FcγR crosslinking, including the Ras pathways, kinases of the MEK and MAP family, as well as transcriptional induction of several cytokine and chemokine genes along with genes involved in cell survival, differentiation, and motility through the activation of transcription factors, such as NF-κB and NFAT (85, 89, 90).

Contrary to the activating, ITAM-bearing FcγRs, two FcγRs, FcγRIIIb and FcγRIIb, have been described that either lack intrinsic signaling capacity or initiate immunosuppressive signals, respectively. As mentioned above, FcγRIIIb is uniquely found in humans and exhibits structural features characterized by the absence of intracellular domains necessary for signaling. Although FcγRIIIb is incapable of transducing intracellular signals following crosslinking by IgG complexes, FcγRIIIb-Fc interactions have been previously shown to result in the induction of cellular activation, mainly through the synergistic activity of FcγRIIIb with other receptors, like FcγRIIa and complement receptors, expressed on the surface of neutrophils (63, 91).

FcγRIIb represents the sole FcγR with inhibitory activity that has the capacity to transduce intracellular signals that directly antagonize the immunostimulatory signals of activating FcγRs. In contrast to the other FcγRII receptors, FcγRIIb comprises an ITIM domain at its intracellular region that mediates inhibitory cellular signaling. Several studies, mainly on B cells, have previously dissected the exact molecular mechanisms of FcγRIIb-mediated cellular inhibition. In particular, co-aggregation of FcγRIIb with activating receptors, like the B cell receptor or activating FcγRs, results in phosphorylation of FcγRIIb ITIM domains, which in turn recruits SHIP and SHP2 phosphatases (68, 92, 93). In the case of FcγRIIb-activating FcγR crosslinking, recruitment of these phosphatases to the FcγRIIb ITIM domains prevent phosphorylation of Syk and Src family kinases, counterbalancing thereby any activating signals originating from activating FcγRs (94, 95). Similarly, on B cells, recruited SHIP and SHP2 phosphatases interfere with B cell receptor signaling by hydrolyzing phosphoinositide intermediates, such as phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate, preventing thereby the recruitment of PH-domain containing kinases, like PLCγ and BTK, and the activation of downstream signaling pathways (68, 93). Since FcγRIIb is the only FcγR with inhibitory activity, it plays a central role in regulating FcγR-mediated inflammation and B cell receptor activity. Indeed, FcγRIIb regulates key processes in B cells, related to cell activation, selection, and antibody production (95, 96), as well as in myeloid cells, like macrophages, influencing the outcome of IgG-mediated inflammation. Several examples from Fcgr2b knock-out mice exist that highlight the importance of FcγRIIb in regulating B cell activation, antibody affinity selection, and antibody serum levels (96, 97). Likewise, genetic deletion of Fcgr2b results in enhanced pro-inflammatory activity in macrophages in murine models of immune complex-mediated alveolitis and collagen-induced arthritis (66, 98–100). Additionally, studies in humans revealed that polymorphisms in the promoter region or transmembrane domain of FcγRIIb that influence receptor expression or activity, respectively are associated with susceptibility to autoimmune disorders, further highlighting the significance of FcγRIIb in maintaining peripheral tolerance and regulate IgG-mediated inflammatory processes (29, 101–104).

As mentioned above, type II FcγRs belong to the C-type lectin family of receptors that exhibit ligand binding specificity exclusively for the “closed” conformation of the IgG Fc domain (5, 8, 9). Two main type II FcγRs have been identified so far: DC-SIGN and CD23 with distinct biological activity in vivo (8, 9, 28, 105)(Figure 2A). Although sialylated IgG Fc binding specificity has been recently shown for other C-type lectin receptors, such as CD22 and DCIR, their precise biological significance has not been fully investigated (106–108). DC-SIGN is encoded by the CD209 genes, which is mapped at the same locus with the genes that codes for CD23 (FCER2), indicative of a common functional and structural origin. Indeed, both CD23 and DC-SIGN are both heavily glycosylated membrane proteins that belong to the C-type lectin receptor superfamily. Since the capacity of type II FcγRs to engage IgG has been recently described, the precise signaling pathways have not been defined as extensively as for type I receptors. However, a number of recent studies have elucidated the mechanisms that regulate IgG binding to type II FcγRs, as well as the downstream biological consequences following receptor engagement (9, 27, 105, 109, 110).

DC-SIGN has the capacity to engage diverse carbohydrate ligands and heavily-glycosylated glycoproteins, including mannose-rich glycan structures, and pathogen surface glycoproteins, such as gp160, the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (28, 111). Binding of these ligands to DC-SIGN is accomplished predominantly through carbohydrate-mediated interactions. In contrast, sialylated IgG Fc – DC-SIGN binding is mediated through protein interactions with the amino acid backbone of the Fc domain at the CH2–CH3 interface; a region that becomes exposed following conformational alterations induced by the Fc-associated glycan structure (8, 9, 28). Since DC-SIGN has the capacity to interact with diverse ligands, downstream signaling cascades following receptor engagement depend largely on the nature of the ligand. In the case of DC-SIGN engagement by sialylated IgG Fc, expression of interleukin 33 (IL-33) is induced following receptor engagement on regulatory macrophages. This effect triggers a robust Th-2 polarizing response that induces potent Treg responses, effectively suppressing Th1- and Th17-mediated inflammation (109, 110). Likewise, IL-33 triggers the production and release of IL-4 by basophils that results in FcγRIIb upregulation on effector myeloid cells, including monocytes and macrophages, at sites of inflammation (109).

CD23 was initially described as a low affinity receptor for IgE; however, recent studies showed that CD23 exhibits ligand binding activity for sialylated IgG in addition to IgE (9, 105). Molecular modeling of the CD23:IgE interaction and the potential CD23:sialylated IgG Fc complex first suggested that CD23 might have the capacity for binding to both ligands (9). IgE interactions with CD23 are largely attributed to the intrinsic flexibility of the Cε3 domain (functionally related to the CH2 domain of IgG). In an analogous model, sialylation of the Fc-associated glycan increases the flexibility of the Cγ2 domain, thereby conferring flexibility to the Fc and enabling Fc interactions with CD23 (9, 112, 113). In terms of expression, CD23 exhibits two splice variants: CD23a and CD23b, which differ both in relation to their expression pattern and responsiveness to IL-4 (114). CD23a is constitutively expressed by B cells, whereas CD23b expression is induced only following IL-4 treatment and is limited to myeloid cells, such as monocytes, macrophages and granulocytes, as well as in certain T cell subsets (114). Apart from sialylated IgG, CD23 can also interact with many other ligands, including CD21, CD11c, and CD11b; however, the functional consequences of these interactions have not been characterized (115).

Cellular effects of FcγR signaling on myeloid cells

FcγR engagement and the associated signaling pathways that are activated upon receptor crosslinking modulate the function of diverse immunoregulatory pathways that shape immune responses, regulate cellular activation and modulate IgG-mediated inflammation (10)(Figure 3). B cells, a lymphoid cell type expressing only one class of each FcγR type (the type I FcγRIIb and the type II CD23) represent a bona fide example of complex FcγR-mediated signaling cellular regulation. In particular, CD23-mediated signaling on B cells following engagement with sialylated IgG complexes modulates the expression of FcγRIIb in these cells (105). Increased FcγRIIb expression on B cells drives the generation of high affinity antibody responses, through the regulation of B cell receptor signaling and modulation of B cell selection (105). Likewise, FcγRIIb on antibody-producing plasma cells regulate cell survival and antibody expression; a key process during the resolution phase of the humoral immune response (93, 97).

Figure 3. Effector functions and processes that are regulated by Fc-FcγR interactions.

Engagement of type I and type II FcγRs by the Fc domain of IgG initiates signaling cascades with diverse pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory consequences on myeloid cells, including granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and platelets.

4In contrast to lymphoid cells, cells of the myeloid lineage, including granulocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, co-express several classes of FcγRs on their surface during all stages of their differentiation. It is therefore anticipated that FcγR engagement in these cells could have diverse immunomodulatory consequences that regulate key processes during an immune response, affecting the outcome of IgG-mediated signaling. Indeed, Fc-FcγR interactions on myeloid cells mediate diverse effector functions including cellular activation, cytotoxicity, and phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized targets (5, 10). Additionally, FcγR-mediated uptake of IgG complexes by phagocytes influences antigen processing and presentation, and regulates the differentiation and maturation of antigen presenting cells, modulating thereby T cell responses (10, 67). Since downstream FcγR signaling leads to the transcriptional activation of several cytokine and chemokine genes, diverse effects from such responses impact cell mobilization, migration, differentiation, and survival. In the next sections, the cellular and biological effects of FcγR signaling initiated upon interactions with the Fc domain of IgG are discussed in detail, focusing on the significance of FcγR pathways in the modulation of myeloid cell functional activity (Figure 3).

Cell Activation

Engagement of ITAM-bearing type I FcγRs by IgG complexes initiates a number of signaling cascades that lead to cellular activation and subsequent induction of effector functions. Cellular responses to Fc-FcγR interactions vary between myeloid cell types; however, FcγR aggregation typically leads to rapid internalization of FcγRs and activation of different signaling pathways that influence cell activation (61, 68, 69, 116). Among myeloid cell types, activation induced upon FcγR engagement is most profound in granulocytes and platelets, as these cell types rapidly mediate biological effects within a few minutes following stimulation with IgG complexes (61, 63, 76, 117, 118). Granulocytes represent the most abundant leukocyte cell type in circulation and mediate pleiotropic effector functions during an inflammatory response to invading pathogens (119). Indeed, granulocytes, which include neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils, are the first leukocyte cell type recruited to sites of inflammation in response to infection or injury and play a central role in immunity against bacterial, viral, and fungal pathogens (120). Several studies have examined the role of FcγR-mediated cellular activation and determined the downstream functional consequences upon FcγR engagement of granulocytes. Granulocyte effector responses initiated following cellular activation in response to Fc-FcγR interactions aim at the destruction of invading pathogens, and involve the release of an array of microbicidal molecules. These molecules are either preformed and stored in specialized granules in the cytoplasm or are rapidly de novo generated (120). Activation of Syk and Src family kinases upon FcγR crosslinking triggers the generation of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) through the formation and activation of the NADPH-dependent oxidase complex; a multi-component protein complex that consists of p40phox, p47phox, p67phox, p22phox, and gp91phox (121–124). Phosphorylation of p47phox promotes its physical association with cytochrome b558, triggering the rapid generation of superoxide anions. Superoxide anions can have direct cytotoxic activity or can lead to the generation of reactive oxygen or nitrogen intermediates, including hydroxyl radical (OHO), hypochlorous acid (HOCl), and peroxynitrite (ONOO−)(122, 125, 126). Additionally, superoxide anions can be dismutated by superoxide dismutase, leading to generation of hydrogen peroxide (127). The release of antimicrobial molecules by granulocytes in response to FcR crosslinking represents one of the most powerful immune mechanisms in the human body. Apart from these chemical compounds, activation of the PKC pathway and increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration following FcγR-mediated cellular activation, triggers the mobilization and release of pre-formed molecules stored in specialized granules (128). The content of these cytoplasmic granules varies among the different granulocyte subtypes; however, it typically comprises proteases (elastase, cathepsins, and collagenases), antimicrobial peptides and proteins (lysozyme, defensins, lactoferrin), enzymes (peroxidase, alkaline phosphatase), lipid mediators (leukotrienes), as well as cell surface receptors (CD11b) (129–135). Release of these mediators at inflammatory sites represents a hallmark for granulocyte activation and constitutes an important effector mechanism by which granulocytes mediate in vivo activity against invading pathogens.

In an analogy to granulocyte activation and degranulation, FcγR-mediated crosslinking also has the capacity to induce platelet activation. Human platelets express FcγRIIa, an activating type I FcγR, which, upon crosslinking, mediates potent signaling activity (136–138). Additionally, they express FcR γ chain, an important accessory signaling subunit for platelet function that associates with several platelet surface receptors, including GPVI (139, 140). Activation of downstream signaling pathways trigger platelet activation and degranulation in a process similar to that observed for granulocytes (141). Elevation of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration following FcγR crosslinking triggers rapid degranulation and release of platelet granule content (139, 142). This includes cell surface receptors that participate in cell-cell adhesion and platelet aggregation, as well as molecules involved in the activation of fibrin cascade, including fibronectin, fibrinogen, and coagulation factors V and XIII (139). Additionally, platelet degranulation is associated with the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-1β, and IL-8, as well as growth factors and pro-survival factors that influence leukocyte cell survival, differentiation, and effector activity (143–145). These events highlight the potential of FcγR-mediated signaling to trigger platelet activation and thrombogenesis, as well as to influence leukocyte function.

Phagocytosis and Antigen Presentation

A common function of all type I FcγRs is their capacity to mediate efficient phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized particles, which can range from small antigens (toxins, infectious pathogens, etc.), to whole cells. Although the phagocytic capacity varies greatly among different myeloid phagocytes, the downstream signaling events and mechanisms that characterize FcγR-mediated phagocytosis follow the general pattern of FcγR crosslinking and cellular activation. In particular, FcγR crosslinking by immune complexes triggers receptor internalization, and activation of downstream signaling pathways that facilitate actin remodeling and endosomal uptake and sorting (10, 63, 77, 83, 146). Although in myeloid cells both activating and inhibitory FcγRs are capable of internalization and phagocytosis, uptake through activating FcγRs mediates more potent effector responses associated with the induction of pro-inflammatory signaling pathways (69, 83, 147). Activation of Syk family kinases upon receptor crosslinking mediates cellular activation, thereby influencing leukocyte effector function. Indeed, activating FcγR-mediated phagocytosis is associated with enhanced endosomal maturation and lysosomal fusion, facilitating antigen processing and presentation on MHC II molecules (69, 148–150). These effects result in the induction of more robust T cell response, further augmenting the in vivo protective activity of antibodies (66, 98, 151, 152).

Several studies have demonstrated the key role of Fc-FcγR interactions in inducing clearance of IgG-coated particles in vivo. For example, seminal experiments using IgG-opsonized erythrocytes demonstrated that their uptake is mediated exclusively through FcγR-mediated pathways by splenic macrophages (153, 154). Likewise, the in vivo activity of antibodies against toxins and bacterial pathogens depends on interactions with FcγRs expressed by effector leukocytes; experimentally, this can be shown using mice that are genetically modified to lack expression of specific FcγRs required for IgG-mediated protection or through modification of the Fc domain on protective antibodies to abrogate FcγR interactions, thus greatly reducing their in vivo activity (58, 155–162). Similarly, clearance of tumors or infected cells targeted by antibodies against surface antigens requires interactions with activating FcγRs (16, 66, 67, 154, 156, 163–167).

Dendritic Cell Maturation

Under homeostatic conditions, human dendritic cells express two type I FcγRs, the inhibitory FcγRIIb and the activating FcγRIIa (5). These receptors are co-expressed on the surface of dendritic cells and activating signals from FcγRIIa engagement are counterbalanced by the inhibitory activity of FcγRIIb, which prevents undesired DC maturation and differentiation. The balance of activating and inhibitory signaling is a key regulatory process controlling DC activity; therefore, the level of expression of these two FcγRs must be tightly regulated. Inflammatory microenvironments can trigger expression of additional activating type I FcγRs, such as FcγRI and FcγRIIIa, as well as influence the expression of FcγRIIb on DCs. For example, IL-4 has been previously shown to induce FcγRIIb upregulation in dendritic cells, whereas IFNγ decreases FcγRIIb expression and stimulates FcγRI expression (46, 109, 151, 168, 169). This finely-tuned balance between activating and inhibitory FcγRs expression and activity determines the threshold for immune complex-mediated dendritic cell activation and responsiveness to PAMPs. Indeed, stimulation of dendritic cells with IgG immune complexes often does not induce robust cell maturation, but requires co-stimulatory signals, such as TLR signaling to overcome the inhibitory activity of FcγRIIb (67, 98, 116, 151, 152, 168, 170). Skewing the balance of the contrasting signaling activity of dendritic cell FcγRIIa and FcγRIIb has profound consequences in cell maturation and the development of subsequent T cell responses. Indeed, genetic deletion or antibody-mediated block of FcγRIIb ligand binding activity on dendritic cells greatly augments immune complex-mediated cell maturation, resulting in the upregulation of MHC and co-stimulatory molecules, as well as in enhanced antigen presentation and T cell activation (116, 151, 152, 168, 171). Likewise, in a model of CD20+ lymphoma, preferential engagement of dendritic cell FcγRIIa through Fc domain engineering of anti-CD20 antibodies, resulted in improved antigen-specific T cell responses; an effect attributed to an increase in the threshold for FcγRIIb-mediated inhibition of dendritic cell maturation (67). These studies highlight the importance of the balancing activity of activating and inhibitory FcγRs in regulating dendritic cell activation, thereby influencing adaptive immune responses.

Macrophage Polarization

Human macrophage populations represent a continuum of diverse activation states with distinct functional and phenotypic characteristics (172). Macrophage polarization has been originally divided into two broad phenotypes – M1 and M2, induced by the contrasting activity of Th1, like IFN-γ and Th2 cytokines, like IL-4, respectively (173). However, it was soon appreciated that immune complex-mediated effector pathways represent an additional determinant for macrophage polarization. In monocytes and polarized macrophages, signaling through the activating FcγRs is associated with the upregulation of several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (10, 58). However, when activating FcγR signaling is coupled with stimulation through TLRs, like TLR4 in non-polarized macrophages, this synergistic signaling activity triggers induction of a specific polarization state that resembles the M2 phenotype (174–176). This phenotype, which is generally termed as M2b or “regulatory”, is characterized by increased IL-10, IL-1 and IL-6 expression as well as by increased migratory and phagocytic capacity (174–176). A number of in vivo studies utilizing mouse strains with genetic deletion of Fcgr2b have provided useful insights into the contribution of FcγR-mediating signaling in regulating macrophage polarization and functional activity. For example, FcγRIIb deficient mice exhibit lower macrophage activation threshold upon challenge with immune complexes and present a more severe phenotype in models of immune complex-induced shock, arthritis, and alveolitis. (100, 153, 174). Also, FcγRIIb expression can determine susceptibility to infection; for example, Fcgr2b−/− mice exhibit improved bacterial clearance in models of pneumococcal peritonitis (177, 178), whereas, overexpression of FcγRIIb is associated with increased mortality upon challenge with Streptococcus pneumoniae (177, 178). These findings highlight the importance of FcγRmediated signaling in macrophage polarization and in the regulation of macrophage effector function in vivo.

Fc receptors in disease

Balanced signaling through Fc receptors is required for proper immune activity and health; indeed, FcγR polymorphisms that affect signaling are associated with a variety of human diseases. In particular, specific autoimmune diseases are more commonly found in association with FcγR polymorphisms that confer lower affinity Fc-FcγR interactions. For example, the R131 variant of FcγRIIa has lower affinity for the IgG2 Fc domain when compared with the H131 form and is more commonly found in people with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)(179), antiphospholipid syndrome (180), myasthenia gravis (181), and severe Guillain-Barre syndrome (182). The frequency of individuals homozygous for either the R131 or H131 variant of FcγRIIa varies between ~25–35% depending on ethnicity (183). In addition, polymorphisms that reduce transcription or disrupt membrane localization of the inhibitory Type I FcR, FcγRIIb are associated with SLE in humans (102–104, 184). The role of FcγRIIb in maintenance of immune tolerance and production of high affinity antibody responses has been studied in some detail; FcγRIIb signaling on B cells increases the threshold for the affinity of B cell receptor that is required for cell survival, thus low FcγRIIb expression or signaling can result in autoantibody and low-affinity antibody production (96, 97, 105). Many FcγR variants have been described and are reviewed elsewhere (29, 185). Studies that provide clear mechanistic evidence for the role of specific FcγRs in health and disease are often performed in animal models. Here, we briefly review works demonstrating the role of specific FcγRs in infection, immunosuppression and cytotoxicity along with clinical studies on FcγR polymorphisms that may support the basic findings.

Immunity to infectious pathogens

Type I FcγRs contribute to protection against a variety of infectious pathogens in vivo. This is exemplified by experiments demonstrating that antibodies specific for influenza virus proteins, which do not exhibit neutralizing activity in vitro, can have protective activity in vivo that depends on activating Type I FcγRs (157, 158). Similarly, suppression of simian-human immunodeficiency virus viremia by anti-HIV mAbs in macaques was dependent on Fc interactions with activating FcγRs (156). Numerous studies have implicated FcγRs in antibody-mediated protection against bacterial, viral and fungal pathogens (58). Clinical studies have found a correlation between the low affinity variant of FcγRIIa (R131) with increased susceptibility to severe bacterial infections and sepsis (186–188), suggesting a protective role for myeloid cell FcγRIIa-mediated effector functions in protection from infection in humans.

Disease enhancing IgG

A long-appreciated yet not fully understood immunomodulatory property of type I FcγRs is their occasional ability to mediate enhanced infectious disease. An example of this phenomenon can be observed in secondary infection with dengue virus; while primary infection is often asymptomatic or mild in presentation, subsequent infection with a distinct dengue serotype can be associated with enhanced viral replication and disease (189, 190). This enhanced secondary disease is, at least in part, thought to be mediated by cross-reactive, non-neutralizing IgGs generated during the primary virus exposure that enhance infection of Type I FcγR bearing cells, including monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells. Antibody-dependent enhancement in dengue virus (DENV) infection has been demonstrated in a variety of in vitro and in vivo DENV infection models, but the mechanisms underlying enhancement are not well understood (191–194). Studies have shown that FcγR-mediated internalization of dengue viruses can result in more infected cells (195, 196), enhanced viral fusion activity (197) and suppression of innate immune signaling (198, 199). Severe DENV disease has been associated with specific combinations of virus serotypes and preexisting serotype immunity (200), viral genetic factors (201–204), and several host factors (205–209).

Antibody-dependent enhancement of disease that is not secondary to increased microbial replication has been observed during respiratory syncytial virus outbreaks in patients previously vaccinated with formalin-inactivated viral proteins and in some severe influenza virus infections. In these circumstances, immune complexes formed from non-neutralizing IgGs with viral proteins are thought to have mediated cytotoxicity and/or complement deposition and inflammation (210, 211). Why some microbes can cause increased infectivity and/or clinical disease through antibody-mediated mechanisms is not well understood. Adaptation to productive replication in monocytes or macrophages may be one determinant of cytokine-associated disease enhancement. A second determinant might be antigenic variability of a pathogen, which often results in production of cross-reactive, non-neutralizing antibodies that can enhance pathogen uptake by FcγR-expressing cells or, in rare circumstances, may form insoluble immune complexes that cause disease due to type I FcγR-mediated inflammation or direct cytotoxicity.

Immunosuppressive IgG

A prime example of immunosuppressive activity through FcγRs is the CD209/DC-SIGN-mediated anti-inflammatory activity achieved clinically through administration of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (28). This activity is dependent on the presence of IgGs modified by glycans with α2,6-linked terminal sialic acid, which induce conformational flexibility of the Fc CH2 domain, enabling binding to Type II receptors. A mechanism underlying the anti-inflammatory signaling induced by IVIG has been described whereby sialylated Fc domains interact with DC-SIGN on regulatory myeloid cells, triggering IL-33 production, which, in turn, induces expansion of IL-4-producing basophils that promote increased expression of the inhibitory Fc receptor FcγRIIb on effector macrophages (109).

Cytotoxic IgG and immunity to tumors

Passively administered anti-tumor mAbs are key therapeutics in a number of cancers and often mediate their cytotoxic effects through mechanisms that depend on FcγR expression on effector myeloid cells (66, 212). FcγRIIIa expression on macrophages has been shown to mediate cytotoxicity of an anti-CD20 mAb in mice that were humanized for Fc receptor expression (67). Several clinical studies support the dependence of cytotoxic mAb activity on FcγRIIIa. Most prominently, the high binding variant of FcγRIIIa, V158, which confers up to ten-fold higher binding to IgG1 and significantly enhanced ADCC activity, has been associated with improved survival in several studies of cancer patients administered antibody therapeutics. Significantly increased response rates and survival are documented in lymphoma patients treated with Rituximab who were heterozygous or homozygous for the FcγRIIIa V158 polymorphism, for example. (213–215). In addition to direct cytotoxicity, long-term anti-tumor immunity has been demonstrated in some patients after administration of Rituximab (216). In mice, induction of anti-tumor immunity by an IgG1 anti-CD20 mAb could be generated by a mechanism dependent on FcγRIIa, expressed on dendritic cells in humans (67).

Conclusions

IgG antibodies recruit effector cells through engagement of Type I and Type II FcγRs. In this way, Fc-FcγR interactions represent a central tie between the humoral and cellular immune divisions. As outlined briefly here, these interactions are essential for immune mechanisms that can protect against against infectious organisms and tumors and can, on occasion, mediate enhanced disease. Antibody therapeutics for the treatment of inflammatory or infectious diseases or cancers require specific effector functions and their development must consider not only target specificity but also downstream effector functions that will be required for optimal therapeutic efficacy.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Rockefeller University and community for its continued support. Research conducted in the Laboratory of Molecular Genetics and Immunology was funded in part by various sponsors including the NIH, the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation, DARPA, CRI, and amfAR.

References

- 1.Netea MG, Wijmenga C, O'Neill LA. Genetic variation in Toll-like receptors and disease susceptibility. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(6):535–542. doi: 10.1038/ni.2284. PubMed PMID: 22610250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gack MU. Mechanisms of RIG-I-like receptor activation and manipulation by viral pathogens. J Virol. 2014;88(10):5213–5216. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03370-13. PubMed PMID: 24623415; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4019093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo JS, Kato H, Fujita T. Sensing viral invasion by RIG-I like receptors. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;20:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.05.011. PubMed PMID: 24968321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sparrer KM, Gack MU. Intracellular detection of viral nucleic acids. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;26:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.03.001. PubMed PMID: 25795286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pincetic A, Bournazos S, DiLillo DJ, Maamary J, Wang TT, Dahan R, et al. Type I and type II Fc receptors regulate innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(8):707–716. doi: 10.1038/ni.2939. PubMed PMID: 25045879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anthony RM, Wermeling F, Ravetch JV. Novel roles for the IgG Fc glycan. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1253:170–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06305.x. Epub 2012/02/01. PubMed PMID: 22288459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borrok MJ, Jung ST, Kang TH, Monzingo AF, Georgiou G. Revisiting the role of glycosylation in the structure of human IgG Fc. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7(9):1596–1602. doi: 10.1021/cb300130k. PubMed PMID: 22747430; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3448853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed AA, Giddens J, Pincetic A, Lomino JV, Ravetch JV, Wang LX, et al. Structural characterization of anti-inflammatory immunoglobulin G Fc proteins. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(18):3166–3179. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.07.006. PubMed PMID: 25036289; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4159253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sondermann P, Pincetic A, Maamary J, Lammens K, Ravetch JV. General mechanism for modulating immunoglobulin effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(24):9868–9872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307864110. PubMed PMID: 23697368; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3683708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bournazos S, Ravetch JV. Fcγ receptor pathways during active and passive immunization. Immunol Rev. 2015;268(1):88–103. doi: 10.1111/imr.12343. PubMed PMID: 26497515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narciso JE, Uy ID, Cabang AB, Chavez JF, Pablo JL, Padilla-Concepcion GP, et al. Analysis of the antibody structure based on high-resolution crystallographic studies. N Biotechnol. 2011;28(5):435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2011.03.012. PubMed PMID: 21477671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krapp S, Mimura Y, Jefferis R, Huber R, Sondermann P. Structural analysis of human IgG-Fc glycoforms reveals a correlation between glycosylation and structural integrity. J Mol Biol. 2003;325(5):979–989. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01250-0. PubMed PMID: 12527303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teplyakov A, Zhao Y, Malia TJ, Obmolova G, Gilliland GL. IgG2 Fc structure and the dynamic features of the IgG CH2-CH3 interface. Mol Immunol. 2013;56(1–2):131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.03.018. PubMed PMID: 23628091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albert H, Collin M, Dudziak D, Ravetch JV, Nimmerjahn F. In vivo enzymatic modulation of IgG glycosylation inhibits autoimmune disease in an IgG subclass-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(39):15005–15009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808248105. PubMed PMID: 18815375; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2567483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lux A, Nimmerjahn F. Impact of differential glycosylation on IgG activity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;780:113–124. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5632-3_10. PubMed PMID: 21842369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Divergent immunoglobulin g subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science. 2005;310(5753):1510–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1118948. PubMed PMID: 16322460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nimmerjahn F, Anthony RM, Ravetch JV. Agalactosylated IgG antibodies depend on cellular Fc receptors for in vivo activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(20):8433–8437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702936104. doi: 0702936104 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0702936104. PubMed PMID: 17485663; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1895967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anthony RM, Nimmerjahn F, Ashline DJ, Reinhold VN, Paulson JC, Ravetch JV. Recapitulation of IVIG anti-inflammatory activity with a recombinant IgG Fc. Science. 2008;320(5874):373–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1154315. Epub 2008/04/19. PubMed PMID: 18420934; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2409116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baudino L, Shinohara Y, Nimmerjahn F, Furukawa J, Nakata M, Martinez-Soria E, et al. Crucial role of aspartic acid at position 265 in the CH2 domain for murine IgG2a and IgG2b Fc-associated effector functions. J Immunol. 2008;181(9):6664–6669. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6664. PubMed PMID: 18941257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrara C, Grau S, Jäger C, Sondermann P, Brünker P, Waldhauer I, et al. Unique carbohydrate-carbohydrate interactions are required for high affinity binding between FcgammaRIII and antibodies lacking core fucose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(31):12669–12674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108455108. PubMed PMID: 21768335; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3150898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shinkawa T, Nakamura K, Yamane N, Shoji-Hosaka E, Kanda Y, Sakurada M, et al. The absence of fucose but not the presence of galactose or bisecting N-acetylglucosamine of human IgG1 complex-type oligosaccharides shows the critical role of enhancing antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(5):3466–3473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210665200. PubMed PMID: 12427744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cramer P, Hallek M, Eichhorst B. State-of-the-Art Treatment and Novel Agents in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Oncol Res Treat. 2016;39(–2):25–32. doi: 10.1159/000443903. PubMed PMID: 26890007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, Engelke A, Eichhorst B, Wendtner CM, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1101–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313984. PubMed PMID: 24401022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Natsume A, Niwa R, Satoh M. Improving effector functions of antibodies for cancer treatment: Enhancing ADCC and CDC. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2009;3:7–16. Epub 2009/11/19. PubMed PMID: 19920917; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2769226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiatt A, Bohorova N, Bohorov O, Goodman C, Kim D, Pauly MH, et al. Glycan variants of a respiratory syncytial virus antibody with enhanced effector function and in vivo efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(16):5992–5997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402458111. PubMed PMID: 24711420; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4000855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shields RL, Lai J, Keck R, O'Connell LY, Hong K, Meng YG, et al. Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(30):26733–26740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202069200. PubMed PMID: 11986321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaneko Y, Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Anti-inflammatory activity of immunoglobulin G resulting from Fc sialylation. Science. 2006;313(5787):670–673. doi: 10.1126/science.1129594. PubMed PMID: 16888140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anthony RM, Wermeling F, Karlsson MC, Ravetch JV. Identification of a receptor required for the anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(50):19571–19578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810163105. Epub 2008/11/28. PubMed PMID: 19036920; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2604916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bournazos S, Woof JM, Hart SP, Dransfield I. Functional and clinical consequences of Fc receptor polymorphic and copy number variants. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157(2):244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03980.x. doi: CEI3980 [pii] 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03980.x. PubMed PMID: 19604264; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2730850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors: old friends and new family members. Immunity. 2006;24(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.010. doi: S1074-7613(05)00383-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.010. PubMed PMID: 16413920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shields RL, Namenuk AK, Hong K, Meng YG, Rae J, Briggs J, et al. High resolution mapping of the binding site on human IgG1 for Fc gamma RI, Fc gamma RII, Fc gamma RIII, and FcRn and design of IgG1 variants with improved binding to the Fc gamma R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(9):6591–6604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009483200. PubMed PMID: 11096108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sondermann P, Huber R, Oosthuizen V, Jacob U. The 3.2-A crystal structure of the human IgG1 Fc fragment-Fc gammaRIII complex. Nature. 2000;406(6793):267–273. doi: 10.1038/35018508. PubMed PMID: 10917521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sondermann P, Kaiser J, Jacob U. Molecular basis for immune complex recognition: a comparison of Fc-receptor structures. J Mol Biol. 2001;309(3):737–749. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4670. PubMed PMID: 11397093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu WQ, de Bruin D, Brownstein BH, Pearse R, Ravetch JV. Organization of the human and mouse low-affinity Fc gamma R genes: duplication and recombination. Science. 1990;248(4956):732–735. doi: 10.1126/science.2139735. PubMed PMID: 2139735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su K, Wu J, Edberg JC, McKenzie SE, Kimberly RP. Genomic organization of classical human low-affinity Fcgamma receptor genes. Genes Immun. 2002;3(Suppl 1):S51–S56. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363879. PubMed PMID: 12215903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ernst LK, van de Winkel JG, Chiu IM, Anderson CL. Three genes for the human high affinity Fc receptor for IgG (Fc gamma RI) encode four distinct transcription products. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(22):15692–15700. PubMed PMID: 1379234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ernst LK, Duchemin AM, Miller KL, Anderson CL. Molecular characterization of six variant Fcgamma receptor class I (CD64) transcripts. Mol Immunol. 1998;35(14–15):943–54. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(98)00079-0. PubMed PMID: 9881690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Vugt MJ, Reefman E, Zeelenberg I, Boonen G, Leusen JH, van de Winkel JG. The alternatively spliced CD64 transcript FcgammaRIb2 does not specify a surface-expressed isoform. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(1):143–149. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199901)29:01<143::AID-IMMU143>3.0.CO;2-#. PubMed PMID: 9933095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiyoshi M, Caaveiro JM, Kawai T, Tashiro S, Ide T, Asaoka Y, et al. Structural basis for binding of human IgG1 to its high-affinity human receptor FcγRI. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6866. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7866. PubMed PMID: 25925696; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4423232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duchemin AM, Ernst LK, Anderson CL. Clustering of the high affinity Fc receptor for immunoglobulin G (Fc gamma RI) results in phosphorylation of its associated gamma-chain. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(16):12111–12117. PubMed PMID: 7512959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ernst LK, Duchemin AM, Anderson CL. Association of the high-affinity receptor for IgG (Fc gamma RI) with the gamma subunit of the IgE receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(13):6023–6027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6023. PubMed PMID: 8327478; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC46859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Indik ZK, Hunter S, Huang MM, Pan XQ, Chien P, Kelly C, et al. The high affinity Fc gamma receptor (CD64) induces phagocytosis in the absence of its cytoplasmic domain: the gamma subunit of Fc gamma RIIIA imparts phagocytic function to Fc gamma RI. Exp Hematol. 1994;22(7):599–606. PubMed PMID: 7516890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Vugt MJ, Heijnen AF, Capel PJ, Park SY, Ra C, Saito T, et al. FcR gamma-chain is essential for both surface expression and function of human Fc gamma RI (CD64) in vivo. Blood. 1996;87(9):3593–3599. PubMed PMID: 8611682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masuda M, Roos D. Association of all three types of Fc gamma R (CD64, CD32, and CD16) with a gamma-chain homodimer in cultured human monocytes. J Immunol. 1993;151(12):7188–7195. PubMed PMID: 8258719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Lee PY, Sobel ES, Narain S, Satoh M, Segal MS, et al. Increased expression of FcgammaRI/CD64 on circulating monocytes parallels ongoing inflammation and nephritis in lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(1):R6. doi: 10.1186/ar2590. PubMed PMID: 19144150; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2688236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uciechowski P, Schwarz M, Gessner JE, Schmidt RE, Resch K, Radeke HH. IFN-gamma induces the high-affinity Fc receptor I for IgG (CD64) on human glomerular mesangial cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28(9):2928–2935. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2928::AID-IMMU2928>3.0.CO;2-8. PubMed PMID: 9754580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maxwell KF, Powell MS, Hulett MD, Barton PA, McKenzie IF, Garrett TP, et al. Crystal structure of the human leukocyte Fc receptor, Fc gammaRIIa. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6(5):437–442. doi: 10.1038/8241. PubMed PMID: 10331870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Radaev S, Motyka S, Fridman WH, Sautes-Fridman C, Sun PD. The structure of a human type III Fcgamma receptor in complex with Fc. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(19):16469–16477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100350200. PubMed PMID: 11297532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Radaev S, Sun P. Recognition of immunoglobulins by Fcgamma receptors. Mol Immunol. 2002;38(14):1073–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00036-6. PubMed PMID: 11955599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maenaka K, van der Merwe PA, Stuart DI, Jones EY, Sondermann P. The human low affinity Fcgamma receptors IIa, IIb, and III bind IgG with fast kinetics and distinct thermodynamic properties. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(48):44898–44904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106819200. PubMed PMID: 11544262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ravetch JV, Bolland S. IgG Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:275–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. doi: 19/1/275 [pii] 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. PubMed PMID: 11244038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brooks DG, Qiu WQ, Luster AD, Ravetch JV. Structure and expression of human IgG FcRII(CD32). Functional heterogeneity is encoded by the alternatively spliced products of multiple genes. J Exp Med. 1989;170(4):1369–1385. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1369. PubMed PMID: 2529342; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2189488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lewis VA, Koch T, Plutner H, Mellman I. A complementary DNA clone for a macrophage-lymphocyte Fc receptor. Nature. 1986;324(6095):372–5. doi: 10.1038/324372a0. PubMed PMID: 3024012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Latour S, Fridman WH, Daëron M. Identification, molecular cloning, biologic properties, and tissue distribution of a novel isoform of murine low-affinity IgG receptor homologous to human Fc gamma RIIB1. J Immunol. 1996;157(1):189–197. PubMed PMID: 8683114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hibbs ML, Bonadonna L, Scott BM, McKenzie IF, Hogarth PM. Molecular cloning of a human immunoglobulin G Fc receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(7):2240–2244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2240. PubMed PMID: 2965389; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC279966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Metes D, Ernst LK, Chambers WH, Sulica A, Herberman RB, Morel PA. Expression of functional CD32 molecules on human NK cells is determined by an allelic polymorphism of the FcgammaRIIC gene. Blood. 1998;91(7):2369–2380. PubMed PMID: 9516136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ernst LK, Metes D, Herberman RB, Morel PA. Allelic polymorphisms in the FcgammaRIIC gene can influence its function on normal human natural killer cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2002;80(4):248–257. doi: 10.1007/s00109-001-0294-2. PubMed PMID: 11976734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bournazos S, DiLillo DJ, Ravetch JV. The role of Fc-FcγR interactions in IgG-mediated microbial neutralization. J Exp Med. 2015;212(9):1361–1369. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151267. PubMed PMID: 26282878; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4548051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hibbs ML, Selvaraj P, Carpén O, Springer TA, Kuster H, Jouvin MH, et al. Mechanisms for regulating expression of membrane isoforms of Fc gamma RIII (CD16) Science. 1989;246(4937):1608–1611. doi: 10.1126/science.2531918. PubMed PMID: 2531918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Masuda M, Verhoeven AJ, Roos D. Tyrosine phosphorylation of a gamma-chain homodimer associated with Fc gamma RIII (CD16) in cultured human monocytes. J Immunol. 1993;151(11):6382–6388. PubMed PMID: 8245472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Unkeless JC, Shen Z, Lin CW, DeBeus E. Function of human Fc gamma RIIA and Fc gamma RIIIB. Semin Immunol. 1995;7(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/1044-5323(95)90006-3. PubMed PMID: 7612894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Selvaraj P, Carpén O, Hibbs ML, Springer TA. Natural killer cell and granulocyte Fc gamma receptor III (CD16) differ in membrane anchor and signal transduction. J Immunol. 1989;143(10):3283–3288. PubMed PMID: 2553809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edberg JC, Kimberly RP. Modulation of Fc gamma and complement receptor function by the glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored form of Fc gamma RIII. J Immunol. 1994;152(12):5826–5835. PubMed PMID: 8207210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith P, DiLillo DJ, Bournazos S, Li F, Ravetch JV. Mouse model recapitulating human Fcgamma receptor structural and functional diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(16):6181–6186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203954109. Epub 2012/04/05. PubMed PMID: 22474370; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3341029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74(7):2527–2534. PubMed PMID: 2478233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med. 2000;6(4):443–446. doi: 10.1038/74704. PubMed PMID: 10742152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.DiLillo DJ, Ravetch JV. Differential Fc-Receptor Engagement Drives an Anti-tumor Vaccinal Effect. Cell. 2015;161(5):1035–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.016. PubMed PMID: 25976835: PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4441863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amigorena S, Bonnerot C, Drake JR, Choquet D, Hunziker W, Guillet JG, et al. Cytoplasmic domain heterogeneity and functions of IgG Fc receptors in B lymphocytes. Science. 1992;256(5065):1808–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1535455. PubMed PMID: 1535455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Amigorena S, Salamero J, Davoust J, Fridman WH, Bonnerot C. Tyrosine-containing motif that transduces cell activation signals also determines internalization and antigen presentation via type III receptors for IgG. Nature. 1992;358(6384):337–341. doi: 10.1038/358337a0. PubMed PMID: 1386408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cosson P, Lankford SP, Bonifacino JS, Klausner RD. Membrane protein association by potential intramembrane charge pairs. Nature. 1991;351(6325):414–416. doi: 10.1038/351414a0. PubMed PMID: 1827877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orloff DG, Ra CS, Frank SJ, Klausner RD, Kinet JP. Family of disulphide-linked dimers containing the zeta and eta chains of the T-cell receptor and the gamma chain of Fc receptors. Nature. 1990;347(6289):189–191. doi: 10.1038/347189a0. PubMed PMID: 2203969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(1):34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. Epub 2007/12/08. PubMed PMID: 18064051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Segal DM, Taurog JD, Metzger H. Dimeric immunoglobulin E serves as a unit signal for mast cell degranulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74(7):2993–2997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2993. PubMed PMID: 70786; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC431378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kulczycki A, Metzger H. The interaction of IgE with rat basophilic leukemia cells. II. Quantitative aspects of the binding reaction. J Exp Med. 1974;140(6):1676–1695. doi: 10.1084/jem.140.6.1676. PubMed PMID: 4214891; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2139755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ishizaka T, Ishizaka K. Triggering of histamine release from rat mast cells by divalent antibodies against IgE-receptors. J Immunol. 1978;120(3):800–805. PubMed PMID: 75922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Salmon JE, Millard SS, Brogle NL, Kimberly RP. Fc gamma receptor IIIb enhances Fc gamma receptor IIa function in an oxidant-dependent and allele-sensitive manner. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(6):2877–2885. doi: 10.1172/JCI117994. PubMed PMID: 7769129; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC295975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sobota A, Strzelecka-Kiliszek A, Gładkowska E, Yoshida K, Mrozińska K, Kwiatkowska K. Binding of IgG-opsonized particles to Fc gamma R is an active stage of phagocytosis that involves receptor clustering and phosphorylation. J Immunol. 2005;175(7):4450–4457. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4450. PubMed PMID: 16177087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Durden DL, Liu YB. Protein-tyrosine kinase p72syk in Fc gamma RI receptor signaling. Blood. 1994;84(7):2102–2108. PubMed PMID: 7522622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Durden DL, Kim HM, Calore B, Liu Y. The Fc gamma RI receptor signals through the activation of hck and MAP kinase. J Immunol. 1995;154(8):4039–4047. PubMed PMID: 7535819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eiseman E, Bolen JB. Engagement of the high-affinity IgE receptor activates src protein-related tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1992;355(6355):78–80. doi: 10.1038/355078a0. PubMed PMID: 1370575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jouvin MH, Adamczewski M, Numerof R, Letourneur O, Vallé A, Kinet JP. Differential control of the tyrosine kinases Lyn and Syk by the two signaling chains of the high affinity immunoglobulin E receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(8):5918–5925. PubMed PMID: 8119935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pignata C, Prasad KV, Robertson MJ, Levine H, Rudd CE, Ritz J. Fc gamma RIIIA-mediated signaling involves src-family lck in human natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1993;151(12):6794–6800. PubMed PMID: 8258691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Swanson JA, Hoppe AD. The coordination of signaling during Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76(6):1093–1103. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804439. PubMed PMID: 15466916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hamawy MM, Minoguchi K, Swaim WD, Mergenhagen SE, Siraganian RP. A 77-kDa protein associates with pp125FAK in mast cells and becomes tyrosine-phosphorylated by high affinity IgE receptor aggregation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(20):12305–12309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12305. PubMed PMID: 7744883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.García-García E, Sánchez-Mejorada G, Rosales C. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and ERK are required for NF-kappaB activation but not for phagocytosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70(4):649–658. PubMed PMID: 11590203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]