Abstract

Background

In the currently available research publications on electrical therapy of low back pain, generally no control groups or detailed randomization were used, and such studies were often conducted with relatively small groups of patients, based solely on subjective questionnaires and pain assessment scales (lacking measurement methods to objectify the therapeutic progress). The available literature also lacks a comprehensive and large-scale clinical study. The purpose of this study was to assess the effects of treating low back pain using selected electrotherapy methods. The study assesses the influence of individual electrotherapeutic treatments on reduction of pain, improvement of the range of movement in lower section of the spine, and improvement of motor functions and mobility.

Material/Methods

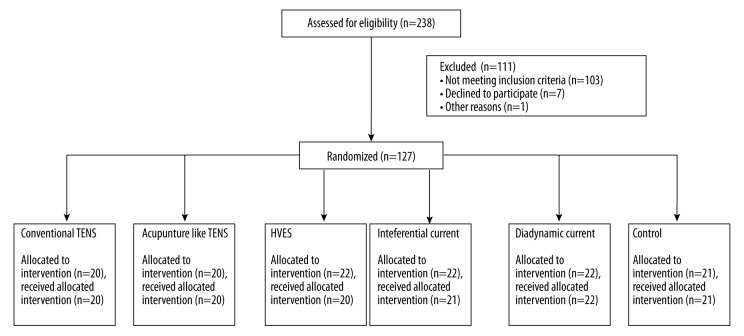

The 127 patients qualified for the therapy (ultimately, 123 patients completed the study) and assigned to 6 comparison groups: A – conventional TENS, B – acupuncture-like TENS, C – high-voltage electrical stimulation, D – interferential current stimulation, E – diadynamic current, and F – control group.

Results

The research showed that using electrical stimulation with interferential current penetrating deeper into the tissues results in a significant and more efficient elimination of pain, and an improvement of functional ability of patients suffering from low back pain on the basis of an analysis of both subjective and objective parameters. The TENS currents and high voltage were helpful, but not as effective. The use of diadynamic currents appears to be useless.

Conclusions

Selected electrical therapies (interferential current, TENS, and high voltage) appear to be effective in treating chronic low back pain.

MeSH Keywords: Electric Stimulation, Low Back Pain, Physical Therapy Specialty

Background

The basic method of treatment for chronic low back pain is conservative treatment, consisting of pharmacotherapy, kinesiotherapy, and physical therapy treatments. Dynamic development of biomedical engineering results in new technical solutions applied in creating new medical devices. The devices that are currently used in physical therapy treatments support, and at times even replace, pharmacological treatment methods. In addition, due to their rare adverse effects, physical methods shorten treatment period, improve quality of life, and reduce therapy costs. One of the physical treatments most frequently used in back pain syndromes is electrical therapy. The main goal of using electrical stimulation in treating low back pain syndromes is an attempt to alleviate both pain and inflammation, as well as to reduce muscle tension in the affected regions [1–3].

However, on the basis of analysis of the available literature on electrotherapeutical methods of low back pain treatment, most studies fail to meet the basic criteria of “evidence-based physiotherapy”, which makes it extremely difficult to carry out a clear and objective analysis of clinical efficacy of treatments that are widely used in everyday practice.

In the currently available research publications on electrical therapy of low back pain, generally no control groups or detailed randomization were used, and such studies were often conducted with relatively small groups of patients, based solely on subjective questionnaires and pain assessment scales (lacking measurement methods to objectify the therapeutic progress). The available literature also lacks any comprehensive and large-scale clinical study analyzing clinical efficacy of the numerous electrotherapeutic methods popular in physiotherapy in a single study, with consistent statistical calculations, which would allow for a reliable assessment of the studied treatments and their comparison to one another, and in relation to a representative control group [4].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the effects of treating low back pain using selected electrical therapies. The study assesses the influence of individual electrotherapeutic treatments on reduction of pain, improvement of the range of movement in lower section of the spine, and improvement of motor functions and mobility.

Material and Methods

Patients’ qualification

The research project was approved by the Bioethics Commission of the Academy of Physical Education in Katowice (no. 10/2012 of 13 December 2012). The study included patients with low back pain, referred for physical therapy to the Clinical Research Lab of the Public Higher Medical Professional School in Opole, Poland.

Qualification of patients was made by a team composed of an orthopedist, a neurologist, a neurosurgeon, an internist, a radiologist, and a physiotherapist. Selection of patients for participation in the study was purposeful. Patients qualified for the study suffered from the L5-S1 discopathy, chronic radiating pain, and pseudoradicular syndrome, and had no previous surgical procedures within the spinal area. The patients were at least 18 years old and had valid certificates of the MRI examination, confirming the diagnosis of low back pain syndrome (at least type III° changes in accordance with the Modic classification in the L5–S1 spine section). On the other hand, the allocation of patients who positively underwent the qualification procedure to specific groups was random (based on a computer number generator). Patients were assigned to 6 comparison groups.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria referred to patients who were diagnosed with: acute pain (less than 6 months), the radicular syndrome, discopathy of other spine regions (patients with early type I and II° changes were not excluded from the study, only the type III° degeneration, as per the Modic classification, constituted grounds for exclusion), no pain or reduction of mobility in the lumbosacral section, other disorders of the spine (spondylolisthesis, fractures, tumors, rheumatic diseases, the cauda equina syndrome), pregnancy, defect symptoms, cardiovascular diseases, pacemakers, metal implants within the application area, sensory disorders, mental disorders, cancer, skin lesions within the area of application of the electrodes, psoriasis, scleroderma, and viral or bacterial infections. Patients who had undergone spinal surgery, as well as those taking painkillers or anti-inflammatory drugs, were also excluded from the study. Exclusion criteria referred also to patients with damage to the vestibule and/or a part of the vestibulocochlear nerve, with Ménière syndrome, vestibular neuritis, sudden loss of function of the inner ear, as well as damage to the cerebellum, spinal cord and brainstem, resulting in balance disorders.

Interventions’ characteristics

A total of 127 patients were qualified for the therapy (ultimately, 124 patients completed the study) and assigned to 6 comparison groups (a flow diagram is presented in Figure 1). Group A consisted of 20 patients (all participants in this group completed the entire study program). Patients were treated with the transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (conventional TENS). Treatment parameters were: alternating current, rectangular impulse, impulse duration 100 μs, frequency of 100 Hz, subjective dosage (until a distinctive sensation of the current flow was experienced, during the patient’s habituation to the electrical stimulus, the therapist gradually increased the intensity during treatment to maintain the desired sensations), and 60-min duration of a single treatment.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Group B consisted of 20 patients (as in the previous group, all the patients completed the therapy). Patients were treated with the transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (acupuncture-like TENS). Treatment parameters were: alternating current, rectangular impulse, impulse duration 200 μs, frequency of 10 Hz, subjective dosage (until distinctive muscle contraction, during habituation and decrease of the motion effect, the therapist gradually increased the intensity during treatment to maintain the desired muscle stimulation threshold), and 60-min duration of a single treatment.

Group C initially consisted of 22 patients, but 2 participants withdrew from further therapy due to viral infection and did not complete the treatment series (1 participant resigned after 4 sessions and the other after 6 sessions). One person had to discontinue the therapy after 3 sessions due to the occurrence of skin lesions within the area of application of the electrodes. In total, group C consisted of 19 patients. These patients were treated using high-voltage electrical stimulation. Treatment parameters were: output voltage 100 V, alternating current, spike impulse, impulse duration 100 μs, frequency of 100 Hz, subjective dosage (until a distinctive sensation of the current flow was experienced, during the patient’s habituation to the electrical stimulus, the therapist gradually increased intensity during treatment to maintain the desired sensations), and 50-min duration of a single treatment.

Group D initially consisted of 22 patients, but 1 person had to resign from further therapy due to aggravation of symptoms and started taking analgesics. Eventually, 21 patients completed the therapy. Subjects in group D were treated with electrotherapy using medium-frequency currents (interferential current stimulation). Treatment parameters were: alternating current, sinusoidal impulse, impulse duration 100 μs, basic frequency 4000 Hz, alternating frequency 50–100 Hz, subjective dosage (until a distinctive sensation of the flowing current was experienced, during the patient’s habituation to the electrical stimulus, the therapist gradually increased the intensity during treatment to maintain the desired sensations), and 20 min duration of a single treatment.

Group E consisted of 22 patients. Patients in this group were treated with electrotherapy using diadynamic currents. Treatment parameters were: pulsed current, sinusoidal impulse, impulse duration and frequency (sequentially DF 10 ms, 100 Hz, CP 10 ms, 50–100 Hz, LP 10 ms, 50–100 Hz, but with an alternating amplitude), subjective dosage (until a distinctive sensation of the flowing current is experienced, during the patient’s habituation to the electrical stimulus the therapist gradually increased the intensity during treatment to maintain the desired sensations), and 9-min duration of a single treatment (DF, LP, and CP were 3 min each).

In all patients treated with physical therapy, the electrodes were placed in the lumbar region in the posterior axillary line (Figures 2, 3).

Figure 2.

Electrode placement in both TENS, HVES, and diadynamic current groups.

Figure 3.

Electrode placement in Inteferiantial current group.

However, patients in group F (21 patients, control group) were treated only by means of motor improvement exercises. The stabilization training [5–7] included: myofascial release techniques for the erector spinae muscle, activation techniques for the neutral position of the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex and deep muscles, training the activation of proper breathing and the transversus abdominis muscle, exercising the coordination of superficial and deep trunk muscles, and postural and dynamic training. Duration of a training session was 45 min (5 times a week, from Monday to Friday).

In the comparison groups A, B, C, D, and E, patients treated with electrical therapy performed basic therapy exercises in accordance with the same methodology as patients in group F. Patients in all the comparison groups (with the exception of group F, in which only the daily motor improvement exercises were used for 3 weeks) were subjected to a series of 15 treatments, 5 times a week (Monday to Friday) for a period of 3 weeks.

The treatments were performed with the Ionoson Expert current generators (Physio Med Electromedizin, Germany), which were calibrated before treatment of each patient using the measurement system and the serial connection of the Ionoson device to a cathodal oscilloscope and a decade resistor (electrical circuit loaded with the resistance of 10 kΩ, as the average resistance of the human body) in order to verify the repeatability, durability, and stability of the treatment parameters generated by the electrostimulator.

Patients in all the comparison groups were homogeneous in terms of basic characteristics specific for the studied populations (Table 1). The groups were also homogeneous as regards the initial measurements concerning pain assessment, functional state, mobility range, and body posture.

Table 1.

Characteristic of study population in each group.

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | Group E | Group F | p – value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n) | |||||||

| Female | 11 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 13 | >0.05 |

| Male | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | |

|

| |||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| Mean | 50.23 | 52.11 | 47.75 | 48.67 | 52.11 | 49.77 | >0.05 |

| SD | 16.34 | 17.03 | 14.84 | 15.19 | 17.21 | 13.67 | |

| Min÷maks | 18–70 | 24–76 | 32–68 | 29–70 | 19–73 | 35–67 | |

|

| |||||||

| Hight (cm) | |||||||

| Mean | 172.11 | 170.34 | 169.08 | 169.26 | 173.21 | 167.22 | >0.05 |

| SD | 9.21 | 8.88 | 8.36 | 8.45 | 10.13 | 7.89 | |

|

| |||||||

| Body mass (kg) | |||||||

| Mean | 76.24 | 77.89 | 75.13 | 76.21 | 78.23 | 73.67 | >0.05 |

| SD | 11.89 | 10.67 | 10.49 | 10.03 | 12.21 | 8.34 | |

|

| |||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| mean | 26.67 | 27.03 | 26.31 | 26.11 | 25.89 | 26.09 | >0.05 |

| SD | 3.89 | 3.93 | 3.71 | 3.45 | 4.01 | 3.14 | |

|

| |||||||

| Obesity (n) | |||||||

| BMI>30 kg/m2 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | >0.05 |

|

| |||||||

| Disease duration (years) | |||||||

| Mean | 4.04 | 3.78 | 3.64 | 3.88 | 4.02 | 3.87 | >0.05 |

| SD | 3.88 | 3.67 | 3.38 | 3.78 | 3.87 | 3.69 | |

|

| |||||||

| Osteoarthritis (n) | |||||||

| Right side | 13 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11 | >0.05 |

| Left side | 7 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

|

| |||||||

| Radiological changes in Modic classification (n) | |||||||

| III° | 14 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 14 | >0.05 |

| IV° | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | |

|

| |||||||

| Pain intensity in VAS (score) | |||||||

| Mean | 7.69 | 7.72 | 7.37 | 7.56 | 7.29 | 7.34 | >0.05 |

| SD | 1.34 | 1.35 | 1.28 | 1.53 | 1.66 | 1.57 | |

|

| |||||||

| Pain intensity in Laitinen (score) | |||||||

| Mean | 8.64 | 8.69 | 8.21 | 8.19 | 8.17 | 8.19 | >0.05 |

| SD | 2.01 | 1.79 | 1.67 | 1.73 | 1.88 | 2.07 | |

|

| |||||||

| Disability level in Oswestry (score) | |||||||

| Mean | 35.11 | 34.95 | 33.04 | 32.88 | 34.33 | 34.30 | >0.05 |

| SD | 5.22 | 5.01 | 4.88 | 4.64 | 4.96 | 5.07 | |

|

| |||||||

| Disability level in Roland-Morris (score) | |||||||

| Mean | 14.05 | 13.97 | 13.83 | 13.71 | 13.86 | 13.83 | >0.05 |

| SD | 2.11 | 2.07 | 2.17 | 2.32 | 2.16 | 2.07 | |

|

| |||||||

| Body posture in coronal plane (mm) | |||||||

| Mean | 192.11 | 190.88 | 190.25 | 192.08 | 190.25 | 189.92 | >0.05 |

| SD | 45.33 | 42.11 | 42.13 | 41.21 | 39.78 | 42.75 | |

|

| |||||||

| Body postuare in sagittal plane (mm) | |||||||

| Mean | 134.33 | 135.21 | 134.00 | 135.66 | 133.45 | 134.00 | >0.05 |

| SD | 34.66 | 32.00 | 36.47 | 41.21 | 39.89 | 38.55 | |

SD – standard deviation; min÷maks – minimal ÷ maximal values.

Pain measurements and functional testing

In order to analyze the therapeutic progress for the subjective assessment of pain and functional capacity as well as the assessment of the degree of disability, the following tests were performed:

The VAS (Visual Analogue Scale) pain assessment scale was used for subjective assessment of the experienced pain, in which the patient assesses the experienced pain on a simple scale from 0 to 10, where 0 denotes lack of pain and 10 denotes the strongest pain.

The modified Laitinen pain scale was used to assess 4 indicators: pain intensity, frequency of pain occurrence, use of analgesics, and limitations of mobility.

The Oswestry questionnaire (The Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, Oswestry Disability Index [ODI]) was used to evaluate the functional ability of patients; it is a widely recognized and reliable scale for evaluation of patients with low back pain. The questionnaire consists of 10 questions regarding symptoms and everyday activities. When answering the individual questions, the patient can choose 1 of the 6 options scored from 0 to 5: A – 0 points; B – 1 point; C – 2 points; D – 3 points; E – 4 points; F – 5 points. After summing the scores for all questions, the Oswestry disability index is as follows: no disability (0–4 points); minimal disability (5–14 points); moderate disability (15–24 points); severe disability (25–34 points); and full disability (35–50 points).

The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RM) was used to assess the degree of disability in patients with low back pain and reflects the condition of the patient on the day of the examination. The questionnaire contains 24 questions which are answered yes or no. Each yes answer scores 1 point and each no answer scores 0 points. After summing the scores for all questions, the Roland-Morris disability index is as follows: no disability (0–3 points); minimal disability (4–10 points); moderate disability (11–17 points); severe disability (18–24 points).

The Lasègue test was used to measure the mobility range in the hip joint on the side of the herniated disc in the course of spinal discopathy. The starting position is lying down on the back with both legs straight. The examiner then slowly lifts one of the patient’s legs while the knee is straight at the joint, until pain occurs. The mobility range is measured in angle degrees using a goniometer.

The Schober test was used for evaluation of mobility of the lumbosacral spine. While the patient is in a standing position, the examiner marks 2 points on the patient’s skin: at 10 cm above the line connecting the posterior superior iliac spines, and then at 5 cm below that line. The patient then slowly bends down as far as possible, while keeping the knees straight. The measurement is made using a tape measure. The obtained result is recorded with an accuracy of up to 0.5 cm.

The mobility range measurements were carried out by the same technician (each measurement was an arithmetic mean of 5 trials). For the purposes of this clinical study, a self-estimation of error of the person performing the measurements was calculated. For each of 15 randomly selected participants, 20 more measurements were taken using the Lasègue test and the Schober’s test (600 measurements in total).

The absolute measurement error (ΔX) was calculated using the formula:

Then the relative error (δX) was estimated, using the formula:

The mean percentage error (relative error expressed in percentage points) was then calculated for all the 20 measurements for the Lasègue and Schober tests. The resulting measurement error, in accordance with the proprietary calculations, was as follows: the arithmetic mean of the measurement error was 5.88%, and the standard deviation was 3.73% for the Lasègue test, and the mean was 3.45%, and the standard deviation was 1.04% for the Schober test. All pain measurements and functional testing were applied before and after treatment.

Stabilometric platform measurements

An objective measurement tool for evaluating postural stability was used. The evaluation was performed using a double-plate stabilographic platform equipped with a computer-aided posturographic system, manufactured by CQ Elektronik System (Poland), model CQ Stab2P. The measurement error was 0.86%. For each patient, 2 trials were carried out: the first trial with eyes open in full visual control, and the second trial with eyes closed, without visual control. The subjects were in a habitual, upright position, standing barefoot on the posturographic platform (feet apart in line with their hips, arms down along their bodies, head facing forward, with eyes fixed on a designated point placed at eye level about 1.5 m away) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Stabilometric platform measurement method.

Statistical analyses of the basic posturographic parameters were performed to compare balance conditions in the tested group of patients. The following parameters were analyzed:

total path length [mm], i.e. the total sway of the center of pressure of the subject’s feet during the trial (30 s), in millimeters; anterio/posterior path length [mm]; medio/lateral path length [mm]; mean amplitude (radius) [mm]; and mean anterio/posterior amplitude [mm].

The above postural stability tests were carried out both before the therapy process and after its completion.

Statistical analysis

The studied parameters were analyzed using the STATISTICA statistical software ver. 10.0 (StatSoft, Dell Inc., USA). The homogeneity of distribution of patients’ characteristics in all groups was analyzed with the chi-square test in the highest reliability version (χ2) and the Kruskal-Wallis homogeneity test. The statistical significance was set at p<0.05. For dependent variables, the nonparametric Wilcoxon’s matched pairs test was used, and for independent variables we used the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis variance analysis. The Tukey post hoc multiple comparisons test was used to identify the exact dependencies resulting from the variance analysis between individual groups. The statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Analysis of results regarding the influence of electrical therapy on the subjective experience of spinal pain

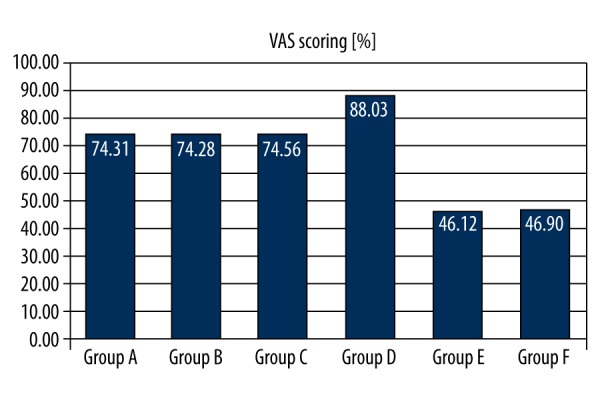

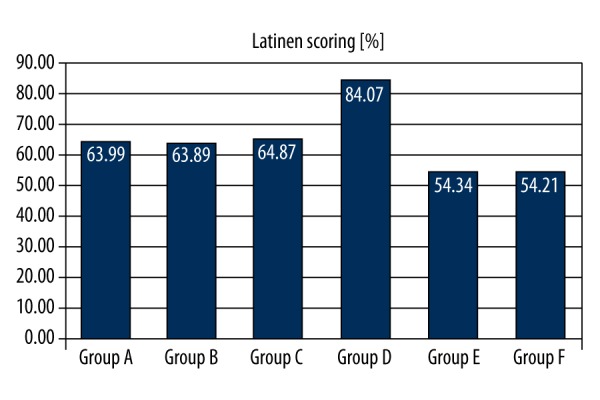

After completion of the therapy, all the comparison groups demonstrated a statistically significant reduction of pain as compared to the initial values, measured using the VAS scale (Table 2). Similarly, a subjective reduction of pain was recorded using the Laitinen questionnaire (Table 3).

Table 2.

Intragroup comparisons of the pain intensity changes in VAS scoring before and after treatment [score].

| Before treatment | After treatment | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Mean | 7.69 | 2.05 | 0.00015 |

| SD | 1.34 | 0.45 | ||

| Group B | Mean | 7.72 | 2.11 | 0.00015 |

| SD | 1.35 | 0.34 | ||

| Group C | Mean | 7.37 | 1.85 | 0.00015 |

| SD | 1.28 | 0.24 | ||

| Group D | Mean | 7.56 | 0.97 | ≤0.0001 |

| SD | 1.53 | 0.31 | ||

| Group E | Mean | 7.29 | 4.05 | 0.0012 |

| SD | 1.66 | 0.78 | ||

| Group F | Mean | 7.34 | 4.11 | 0.0012 |

| SD | 1.57 | 0.69 |

VAS – visual-analogue scale; SD – standard deviation.

Table 3.

Intragroup comparisons of the pain intensity changes in Laitinen scoring before and after treatment [score].

| Before treatment | After treatment | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Mean | 8.64 | 3.19 | 0.00014 |

| SD | 2.01 | 1.13 | ||

| Group B | Mean | 8.69 | 3.25 | 0.00016 |

| SD | 1.79 | 1.12 | ||

| Group C | Mean | 8.21 | 2.87 | 0.00014 |

| SD | 1.67 | 0.89 | ||

| Group D | Mean | 8.19 | 1.11 | ≤0.0001 |

| SD | 1.73 | 0.51 | ||

| Group E | Mean | 8.17 | 3.69 | 0.0021 |

| SD | 1.88 | 1.18 | ||

| Group F | Mean | 8.19 | 3.74 | 0.002 |

| SD | 2.07 | 1.22 |

SD – standard deviation.

However, the intergroup analysis demonstrated that the highest analgesic effect was recorded in group D (interferential current stimulation), which proved to be a significantly better result than in groups A (conventional TENS), B (acupuncture-like TENS), and C (high-voltage electrical stimulation [HVES]). No statistically significant differences were observed between groups A, B, and C. The lowest analgesic effect was observed in group E (diadynamic currents [DD]) and F (control group), at a similar level in both groups. The above was confirmed both by the results of measurements performed using the VAS scale (Figure 5) and the Laitinen questionnaire (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Intergroup comparisons of the pain intensity reduction in VAS scoring [%]. P (A,B,C,D,E,F)=0.034. Post hoc analysis: p(A,B)>0.05; p(A,C)>0.05; p(A,D)=0.041; p(A,E)=0.014; p(A,F)=0.016; p(B,C)>0.05; p(B,D)=0.038; p(B,E)=0.012; p(B,F)=0.012; p(C,D)=0.045; p(C,E)=0.012; p(C,F)=0.012; p(D,E)=0.001; p(D,F)=0.001; p(E,F)>0.05.

Figure 6.

Intragroup comparisons of the pain intensity reduction in Laitinen scoring [%]. P (A,B,C,D,E,F)=0.026. Post hoc analysis: p(A,B)>0.05; p(A,C)>0.05; p(A,D)=0.018; p(A,E)=0.044; p(A,F)=0.044; p(B,C)>0.05; p(B,D)=0.018; p(B,E)=0.045; p(B,F)=0.044; p(C,D)=0.018; p(C,E)=0.045; p(C,F)=0.045; p(D,E)=0.001; p(D,F)=0.001; p(E,F)>0.05.

Analysis of results regarding the influence of electrical therapy on the subjective experience of functional ability in patients with low back pain

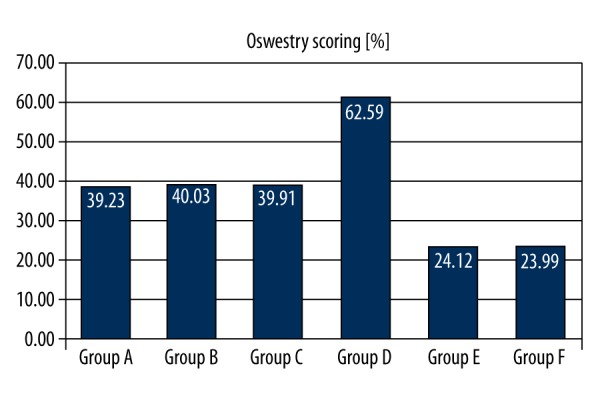

After 3 weeks of treatment, all the comparison groups demonstrated a statistically significant improvement of functional ability, measured using the Oswestry questionnaire (Table 4). Similarly, a subjective improvement of patients’ ability was recorded using the Roland-Morris questionnaire (Table 5).

Table 4.

Intragroup comparisons of the disability level changes in Oswestry scoring before and after treatment [score].

| Before treatment | After treatment | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Mean | 35.11 | 22.05 | 0.00017 |

| SD | 5.22 | 3.19 | ||

| Group B | Mean | 34.95 | 21.87 | 0.00022 |

| SD | 5.01 | 3.21 | ||

| Group C | Mean | 33.04 | 19.95 | 0.00022 |

| SD | 4.88 | 3.07 | ||

| Group D | Mean | 32.88 | 12.05 | ≤0.0001 |

| SD | 4.64 | 2.71 | ||

| Group E | Mean | 34.33 | 26.05 | 0.0014 |

| SD | 4.96 | 3.43 | ||

| Group F | Mean | 34.30 | 26.01 | 0.0014 |

| SD | 5.07 | 3.87 |

SD – standard deviation.

Table 5.

Intragroup comparisons of the disability level changes in Roland – Morris scoring before and after treatment [score].

| Before treatment | After treatment | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Mean | 14.05 | 4.88 | 0.00055 |

| SD | 2.11 | 1.34 | ||

| Group B | Mean | 13.97 | 3.69 | 0.00046 |

| SD | 2.07 | 1.11 | ||

| Group C | Mean | 13.83 | 4.64 | 0.0005 |

| SD | 2.12 | 1.27 | ||

| Group D | Mean | 13.71 | 2.03 | ≤0.0001 |

| SD | 2.32 | 0.91 | ||

| Group E | Mean | 13.86 | 5.88 | 0.0012 |

| SD | 2.16 | 1.67 | ||

| Group F | Mean | 13.83 | 5.80 | 0.001 |

| SD | 2.07 | 1.72 |

SD – standard deviation.

However, on the basis of an intergroup analysis, we found that the highest percentual improvement of the patients’ functional ability measured with the Oswestry questionnaire took place in group D (interferential current stimulation), giving a significantly more beneficial effect than in groups A (conventional TENS), B (acupuncture-like TENS), and C (HVES). No statistically significant differences were observed between groups A, B, and C. The lowest effect was observed in group E (DD) and F (control group), at a similar level in both groups (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Intergroup comparisons of the disability level diminishment in Oswestry scoring [%]. P (A,B,C,D,E,F)=0.012. Post hoc analysis: p(A,B)>0.05; p(A,C)>0.05; p(A,D)=0.028; p(A,E)=0.036; p(A,F)=0.036; p(B,C)>0.05; p(B,D)=0.031; p(B,E)=0.037; p(B,F)=0.038; p(C,D)=0.028; p(C,E)=0.038; p(C,F)=0.038; p(D,E)=0.001; p(D,F)=0.001; p(E,F)>0.05.

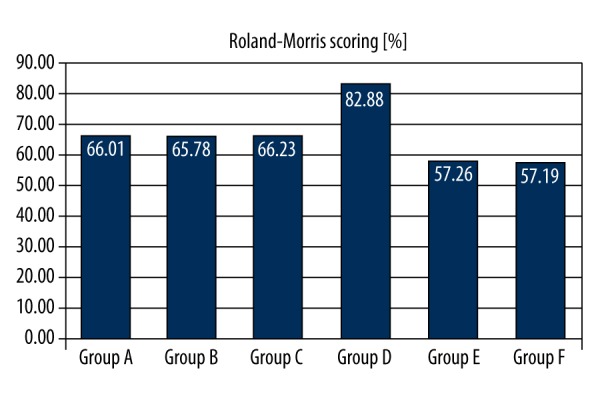

In case of intergroup comparisons regarding the subjective experience of ability measured with the Roland-Morris questionnaire, the greatest progress was observed in group D (interferential current stimulation). In the remaining groups, the results were significantly statistically worse (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Intergroup comparisons of the disability level diminishment in Roland-Morris scoring [%]. p(A,B,C,D,E,F)=0.055 (close to the significant level). Post hoc analysis: p(A,B)>0.05; p(A,C)>0.05; p(A,D)=0.035; p(A,E)>0.05; p(A,F)>0.05; p(B,C)>0.05; p(B,D)=0.038; p(B,E)>0.05; p(B,F)>0.05; p(C,D)=0.033; p(C,E)>0.05; p(C,F)>0.05; p(D,E)=0.037; p(D,F)>0.05; p(E,F)>0.05.

Analysis of results regarding the influence of electrical therapy on hip mobility range on the affected side and in the low back region

Immediately after completion of therapy, the comparison groups demonstrated a statistically significant increase of mobility in the hip joint as compared to the pre-therapy state, measured using the Lasègue test (Table 6). An improved mobility in the low back region was also recorded in the Schober’s test (Table 7).

Table 6.

Intragroup comparisons of the hip join mobility changes in Lasègue testing before and after treatment [degree].

| Before treatment | After treatment | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Mean | 56.70 | 69.10 | 0.0011 |

| SD | 7.40 | 10.80 | ||

| Group B | Mean | 56.55 | 68.95 | 0.0012 |

| SD | 7.25 | 10.30 | ||

| Group C | Mean | 58.80 | 71.70 | 0.0012 |

| SD | 7.70 | 10.20 | ||

| Group D | Mean | 58.65 | 80.50 | ≤0.0001 |

| SD | 7.35 | 10.45 | ||

| Group E | Mean | 59.80 | 65.55 | 0.0036 |

| SD | 7.10 | 10.75 | ||

| Group F | Mean | 59.70 | 64.50 | 0.0037 |

| SD | 7.55 | 9.95 |

SD – standard deviation.

Table 7.

Intragroup comparisons of the lower Th mobility changes in Schober testing before and after treatment [cm].

| Before treatment | After treatment | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Mean | 3.25 | 4.50 | 0.0032 |

| SD | 1.55 | 3.35 | ||

| Group B | Mean | 3.20 | 4.45 | 0.0032 |

| SD | 1.45 | 3.45 | ||

| Group C | Mean | 3.30 | 4.60 | 0.003 |

| SD | 1.75 | 4.15 | ||

| Group D | Mean | 3.35 | 5.10 | 0.0016 |

| SD | 1.35 | 4.85 | ||

| Group E | Mean | 3.45 | 4.05 | 0.0044 |

| SD | 1.40 | 3.70 | ||

| Group F | Mean | 3.40 | 4.05 | 0.0044 |

| SD | 1.55 | 3.70 |

SD – standard deviation.

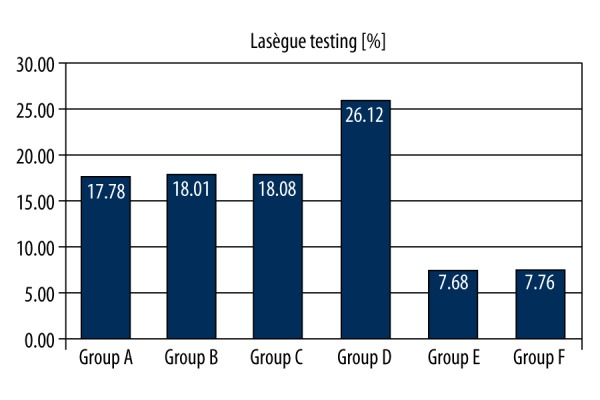

On the basis of an intergroup analysis, we found that the highest percentual improvement in the Lasègue test took place in group D (interferential current stimulation), giving a significantly better result than in groups A (conventional TENS), B (acupuncture-like TENS), and C (HVES). No statistically significant differences were observed between groups A, B, and C. The least progress was recorded in group E (DD) and F (control group), at a similar level in both groups (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Intergroup comparisons of the hip join mobility improvement in Lasègue testing [%]. p(A,B,C,D,E,F)=0.031. Post hoc analysis: p(A,B)>0.05; p(A,C)>0.05; p(A,D)=0.041; p(A,E)=0.018; p(A,F)=0.018; p(B,C)>0.05; p(B,D)=0.043; p(B,E)=0.017; p(B,F)=0.018; p(C,D)=0.046; p(C,E)=0.018; p(C,F)=0.018; p(D,E)=0.001; p(D,F)=0.001; p(E,F)>0.05.

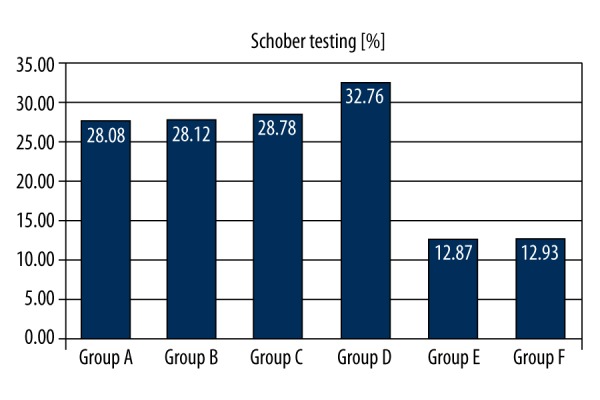

The comparison of intergroup results of the Schober’s test indicated that groups A (conventional TENS), B (pseudo-acupuncture TENS), C (HVES), and D (interference currents) gained a significant advantage over groups E (DD) and F (control group) (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Intergroup comparisons of the lower Th mobility improvement in Schober testing [%]. p(A,B,C,D,E,F)=0.036. Post hoc analysis: p(A,B)>0.05; p(A,C)>0.05; p(A,D)>0.05; p(A,E)=0.018; p(A,F)=0.020; p(B,C)>0.05; p(B,D)>0.05; p(B,E)=0.015; p(B,F)=0.016; p(C,D)>0.05; p(C,E)=0.018; p(C,F)=0.014; p(D,E)=0.008; p(D,F)=0.008; p(E,F)>0.05.

Analysis of the results regarding the influence of electrical therapy on body posture parameters measured using the stabilometric platform

After completion of therapy, tests on the stabilometric platform clearly demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in body posture as regards the total path length of sway of the center of pressure during a time trial (Table 8) and the path length in the anterio-posterior sway (Table 9) in comparison to the initial state. These parameters were significantly reduced in all the comparison groups (in particular with eyes closed), which confirms that patients with low back pain had a more stable body posture after the therapy. In case of measurement of the path in the lateral sway, a beneficial reduction was also recorded in the studied groups, although these changes were not statistically significant (Table 10).

Table 8.

Intragroup comparisons of the SP parameter changes in stabilometric examination with open and closed eyes before and after treatment [mm].

| Open eyes | p-value | Closed eyes | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | ||||

| Group A | Mean | 192.11 | 185.34 | 0.011 | 267.89 | 255.88 | 0.0042 |

| SD | 45.33 | 27.22 | 56.77 | 39.05 | |||

| Group B | Mean | 190.88 | 184.02 | 0.01 | 268.44 | 257.73 | 0.0043 |

| SD | 42.11 | 22.87 | 55.33 | 34.11 | |||

| Group C | Mean | 190.25 | 183.66 | 0.011 | 267.33 | 258.33 | 0.0042 |

| SD | 42.13 | 24.83 | 58.16 | 37.28 | |||

| Group D | Mean | 192.08 | 172.27 | 0.0012 | 266.92 | 234.33 | 0.00078 |

| SD | 41.21 | 20.75 | 49.34 | 34.21 | |||

| Group E | Mean | 190.25 | 185.12 | 0.011 | 268.05 | 260.18 | 0.0047 |

| SD | 39.78 | 21.79 | 50.44 | 39.66 | |||

| Group F | Mean | 189.92 | 186.05 | 0.011 | 267.21 | 259.15 | 0.0047 |

| SD | 42.75 | 23.32 | 46.99 | 35.62 | |||

SP – total path length on both coronal (left/right) and sagittal (front/back) axes [mm]; SD – standard deviation.

Table 9.

Intragroup comparisons of the SPAP parameter changes in stabilometric examination with open and closed eyes before and after treatment [mm].

| Open eyes | p-value | Closed eyes | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | ||||

| Group A | Mean | 134.33 | 124.33 | 0.022 | 213.12 | 206.89 | 0.031 |

| SD | 34.66 | 20.12 | 66.66 | 40.85 | |||

| Group B | Mean | 135.21 | 126.50 | 0.022 | 214.11 | 207.66 | 0.032 |

| SD | 32.00 | 20.80 | 67.33 | 45.45 | |||

| Group C | Mean | 134.00 | 125.50 | 0.02 | 212.33 | 206.33 | 0.03 |

| SD | 36.47 | 22.09 | 63.73 | 43.80 | |||

| Group D | Mean | 135.66 | 120.33 | 0.0018 | 212.50 | 200.50 | 0.0012 |

| SD | 41.21 | 20.75 | 58.88 | 45.34 | |||

| Group E | Mean | 133.45 | 124.50 | 0.025 | 212.33 | 205.78 | 0.036 |

| SD | 39.89 | 22.50 | 62.56 | 44.44 | |||

| Group F | Mean | 134.00 | 125.12 | 0.025 | 213.01 | 206.87 | 0.036 |

| SD | 38.55 | 27.20 | 66.09 | 45.88 | |||

SPAP – statokinesiogram path length on the sagittal plane (front/back) [mm]; SD – standard deviation.

Table 10.

Intragroup comparisons of the SPML parameter changes in stabilometric examination with open and closed eyes before and after treatment [mm].

| Open eyes | p-value | Closed eyes | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | ||||

| Group A | Mean | 109.00 | 104.33 | >0.05 | 118.88 | 113.21 | >0.05 |

| SD | 21.34 | 14.12 | 13.56 | 9.78 | |||

| Group B | Mean | 108.35 | 103.50 | >0.05 | 119.64 | 112.76 | >0.05 |

| SD | 23.12 | 14.57 | 14.55 | 9.89 | |||

| Group C | Mean | 108.33 | 104.00 | >0.05 | 119.83 | 112.83 | >0.05 |

| SD | 22.04 | 15.82 | 14.95 | 9.74 | |||

| Group D | Mean | 109.50 | 105.50 | >0.05 | 119.34 | 112.03 | >0.05 |

| SD | 20.11 | 15.05 | 14.22 | 10.04 | |||

| Group E | Mean | 108.50 | 104.50 | >0.05 | 118.03 | 113.12 | >0.05 |

| SD | 21.44 | 16.53 | 13.89 | 10.12 | |||

| Group F | Mean | 109.30 | 105.33 | >0.05 | 118.23 | 114.02 | >0.05 |

| SD | 23.11 | 14.09 | 15.36 | 10.37 | |||

SPML – statokinesiogram path length on the coronal plane (left/right) [mm]; SD – standard deviation.

Interesting changes occurred in measurements of the mean radius of the center of pressure sway, as the beneficial reduction of this parameter and improvement of postural stability took place in the closed-eyes trial (Table 11). In trials under visual control, the radius was also reduced in all groups, but this change was significantly smaller.

Table 11.

Intragroup comparisons of the MA parameter changes in stabilometric examination with open and closed eyes before and after treatment [mm].

| Open eyes | p-value | Closed eyes | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | ||||

| Group A | Mean | 1.61 | 1.57 | >0.05 | 3.15 | 2.92 | 0.022 |

| SD | 0.74 | 0.63 | 1.56 | 1.24 | |||

| Group B | Mean | 1.60 | 1.58 | >0.05 | 3.17 | 2.96 | 0.024 |

| SD | 0.70 | 0.65 | 1.43 | 1.75 | |||

| Group C | Mean | 1.60 | 1.58 | >0.05 | 3.18 | 2.95 | 0.023 |

| SD | 0.71 | 0.65 | 1.48 | 1.20 | |||

| Group D | Mean | 1.61 | 1.57 | >0.05 | 3.18 | 2.80 | 0.0013 |

| SD | 0.77 | 0.60 | 1.47 | 1.56 | |||

| Group E | Mean | 1.60 | 1.59 | >0.05 | 3.17 | 2.94 | 0.021 |

| SD | 0.76 | 0.64 | 1.37 | 1.44 | |||

| Group F | Mean | 1.59 | 1.57 | >0.05 | 3.17 | 2.95 | 0.021 |

| SD | 0.72 | 0.68 | 1.49 | 1.78 | |||

MA – the mean amplitude (radius) of the centre of pressure, on both axes [mm]; SD – standard deviation.

Similar tendencies were also observed for other stabilometric parameters. The analysis of variance showed that the greatest percentual reduction in the length of the total path of the center of pressure sway in a time trial occurred in group D (interference currents). These parameters were also slightly reduced in the remaining groups, especially group A (conventional TENS), B (acupuncture-like TENS), and C (HVES), but despite this trend, no statistically significant difference was obtained in relation to groups E (DD) and F (control group). A similar situation was observed in the case of closed-eyes trial, where group D had an even more significant advantage over the other groups.

The analysis of percentual shortening of the path length in the anterio-posterior sway of the patients’ center of pressure indicates that the outcome of this process was the most beneficial in group D (interferential current stimulation). In the remaining groups, the phenomenon occurred with a slightly lower intensity. However, no statistically significant differences were found between the studied groups. The situation was identical in the eyes-closed test.

On the other hand, in the percentage analysis of reduction of the mean radius of center of pressure sway in trials under visual control, there were no significant changes, and the recorded changes occurred at a similar level in all groups. Interestingly, in the eyes-closed trial, patients in group D (interferential current stimulation) had better scores than those obtained in other groups. However, no statistically significant differences were detected, although an evident trend was observed regarding changes in benefit of group D in relation to the other groups.

Observation of the percentual reduction of the mean lateral sway of the center of pressure in the eyes-open trial did not show a visible improvement of this parameter in the studied groups (reduction of sway was small and occurred at a similar level in all patients irrespectively of the treatment method). No statistically significant intergroup differences were noted. All the more interesting was the significant advantage of group D (interferential current stimulation) in relation to the other groups during the trial without visual control. In group D, a statistically significant difference was noted in relation to other groups. Similar tendencies occurred in other analyses.

Discussion

Chronic low back pain most frequently affects persons over 40 years of age. This condition may also cause pain radiating along the lower limbs, muscle weakness due to compression and irritation of nerve roots, as well as limitation of spinal mobility. These symptoms may appear at any stage of the disease, disturbing the function of the locomotor system. They are also a cause of disability and related social factors, which entails increased expenditure on, among others, diagnostics and treatment [5].

Therefore, it is necessary to search for effective treatment methods for back pain syndromes. One of the treatment methods is physical therapy, which helps to reduce the disease symptoms. Thus, many researchers express a considerable interest in this subject. Although the available literature contains a large number of proposals for conservative treatment of low back pain using electrical therapy, such publications usually concern only 1 type (or, in some cases, 2 types in a direct comparison under 1 clinical study) of electric current. Such articles contain a number of limitations and weaknesses, which makes it difficult to carry out an unequivocal clinical assessment [4].

Studies conducted by Brazilian researchers confirm the high effectiveness of interference currents and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in low back pain therapy. Facci et al. [8] compared the effects of the TENS treatment and interferential current stimulation (IFC) treatment in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain. The study involved a group of 150 patients, randomly assigned to 3 comparison groups. The first group consisted of patients who were treated with TENS therapy, the second group was treated with the IFC currents, and the third group was not treated with any physical stimulus. Patients in the first and second group underwent treatment for 30 min during 10 consecutive days. In all patients, pain level was assessed using the visual analogue pain scale (VAS) and the McGill pain questionnaire. Evaluation of disability was also conducted using the Roland-Morris questionnaire. Results of the study demonstrate that the TENS and IFC therapy brought about significant effects as in reduction of pain intensity, improvement of disability, and reduction in the amount of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs used, in comparison to the control group. However, no significant differences were noted between patients from the first and the second group.

Other Brazilian researchers evaluated the effectiveness of the interferential current stimulation (IFC) therapy. Correa et al. [9] conducted a randomized clinical trial involving 150 patients with a chronic, nonspecific low back pain syndrome, which confirmed the beneficial therapeutic effect of the IFC.

Similarly, Lara-Palomo et al. [10] demonstrated in their publication that the effectiveness of interferential currents was higher than that of superficial massage applied to the lumbar region of the spine. The study involved 62 persons divided into 2 groups. Patients from the first group were subjected to a series of treatments using IFC, whereas patients in the second group underwent a series of massage treatments. In both groups, treatments were performed for 10 weeks (a total of 20 treatments, 2 times a week). Subjective pain assessment was performed using the visual analogue pain scale (VAS), while the Oswestry and the Roland-Morris questionnaires were used to evaluate the functional ability of patients. After the completed therapy, it was found that in comparison to superficial massage, the interference current led to significantly more improvement of disability, reduction of pain, and increase of quality of life.

Turkish researchers demonstrated that TENS and exercise increased quality of life and reduced pain in patients with low back pain. Dogan et al. [11] evaluated 3 types of therapy in a 60-person group. In the first group patients performed aerobic and general development exercises, the second group performed general development exercises and was treated with physical therapy (conventional TENS), and in the third group the patients performed only general development exercises. Before the therapy and after its completion, spine mobility was assessed with Schober’s test, pain intensity was assessed with the visual analogue pain scale (VAS), and the disability assessment was performed using the Roland-Morris questionnaire. An assessment was also made of the general mental condition of patients, using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). On the basis of the obtained effects, only the second study group demonstrated a statistically significant improvement as regards the measured parameters and the experienced pain.

However, the literature also provides examples of cases where electrotherapy had low effectiveness or only a short-term analgesic effect. McLoughlin et al. [12] indicated a lack of analgesic effect after the application of high-voltage electrical stimulation.

Ambiguous results of a study in which TENS was used in therapy of low back pain was presented in a publication by Buchmuller et al. [13]. The study involved 236 persons suffering from low back pain, from 21 treatment centers in France. The patients were randomly assigned to 2 groups. The first group was made up of 117 patients who were treated with active TENS treatments, while the second group, consisting of 119 patients, was subjected to simulated TENS treatments. The functional state of patients was assessed using the Roland-Morris questionnaire, and pain intensity was measured in accordance with the visual analogue pain scale (VAS). Surveys were conducted before the commencement of the therapy, after 2 and 6 weeks, and at 3 months after completion of the study. Independently of the study report, patients kept a diary to record their assessment of the intensity of pain. Analysis of the obtained results demonstrated similar reactions in the group of patients who underwent the active TENS treatments and in the placebo group as regards the assessment of functional state and in relation to the VAS scale. However, the assessments of pain intensity recorded in patients’ diaries demonstrated a highly significant difference in favor of the active TENS treatments, which shows a strong placebo effect of this method.

In the meta-analysis presented by Khadilkar et al. [14], whose aim was to determine the effectiveness of TENS in the therapy of chronic pain of the lumbar section of the spine, a series of equivocal data was recorded, confirming the use of the TENS as an analgesic. The authors, while performing an in-depth assessment, noted inter alia the non-uniform methodology, the discrepancies in inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the differing therapy durations. These differences could have contributed to the inconsistent results. It would be valuable to have results from a large, multi-center research project using control groups (quasi-electrotherapy) and thorough randomization, as well as to unify the methodology of the performed treatments. Particular attention should be given to the long-term benefits which may possibly be observed after the application of TENS.

Strength/weakness of the study

The novelty of our study consists in an unambiguous assessment of popular methods of electrical therapy used in low back pain treatment under a single, prospective, randomized clinical pilot trial, based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, using both modern objective measurements and subjective measurements, with a uniform statistical analysis and a comprehensive and multi-faceted observation of the achieved results. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first wide-ranging scientific study of low back pain electrotherapy in accordance with the guidelines of the “Evidence-Based Physiotherapy”. None of the current publications made such a detailed diagnostics or a classification based on the radiological Modic assessment criteria. This allowed for a very representative population, which was recruited for the purpose of this project. In addition, other researchers did not use calibration of the electrostimulator before each treatment.

Irrespective of the innovative character of our pilot research and the elements of novelty, this work also contains a number of limitations. It would certainly be worthwhile to supplement the project in the future with other modern and objective measurement tools, such as muscle electromyography, the Biodex system movement analysis, and tensiometry. Also, the study did not involve “blind trials” or placebo effect assessment. In 1 of the comparison groups, patients underwent only the standard functional training and were not treated with any electrotherapeutical treatment whatsoever, which constituted a point of reference in relation to the exposed groups and which is permitted in the methodology of medical research publications. However, using the “simulated” treatments and the so-called “single-blind trial” would certainly constitute an interesting addition and would also significantly raise the profile of this study. A weakness of this research was also the relatively high measurement error (although in most cases the researchers do not even perform this kind of analysis or self-reflection) during the observation of mobility of the hip joint and the lumbar region of the spine. We endeavored to mitigate it by making our own error estimations and by making sure that all measurements were made by the same person (an average of the 5 performed trials). The above deficiencies certainly impose certain limitations on our research. In future, it will also be necessary to perform an assessment of remote results, which will allow us to estimate the sustainability of remission achieved due to electrical therapy.

Conclusions

Our conducted research indicates that using electrostimulation with interferential current stimulation penetrating deeper into the tissues results in a significant and long-term elimination of pain, and an improvement of functional ability of patients suffering from low back pain on the basis of an analysis of both subjective and objective parameters. Although TENS currents and HVES are helpful in treatment of discopathy of the lower region of the spine, use of interference currents led to greater remission of symptoms. On the other hand, the research indicates that the use of diadynamic currents appears to be useless in the course of degenerative proliferative disease of the spine (within the scope studied in this paper).

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Bilgin S, Temucin CM, Nurlu G, et al. Effects of exercise and electrical stimulation on lumbar stabilization in asymptomatic subjects: A comparative study. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2013;26:261–66. doi: 10.3233/BMR-130374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hazime FA, de Freitas DG, Monteiro RL, et al. Analgesic efficacy of cerebral and peripheral electrical stimulation in chronic nonspecific low back pain: A randomized, double-blind, factorial clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;31:7–12. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0461-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SY, Kim JH, Jung GS, et al. The effects of transcutaneous neuromuscular electrical stimulation on the activation of deep lumbar stabilizing muscles of patients with lumbar degenerative kyphosis. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28:399–406. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Kuijpers T, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:19–39. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1518-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delito A, George SZ, Van Dilen L, et al. Low back pain: Clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee HS, Kim YH, Sung PS. A randomized controlled trial to determine the effect of spinal stabilization exercise intervention based on pain level and standing balance differences in patients with low back pain. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(3):CR174–81. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szulc P, Wendt M, Waszak M, et al. Impact of McKenzie method therapy enriched by muscular energy techniques on subjective and objective parameters related to spine function in patients with chronic low back pain. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:2918–32. doi: 10.12659/MSM.894261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Facci LM, Nowotny JP, Tormem F, Trevisani VF. Effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and interferential currents (IFC) in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain: randomized clinical trial. Sao Paulo Med J. 2011;129:206–16. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802011000400003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corrêa JB, Pena Costa LO, Bastos de Oliveira NT, et al. Effects of the carrier frequency of interferential current on pain modulation in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: A protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:195–201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lara-Palomo IC, Aguilar-Ferrándiz EM, Matarán-Peñarrocha GA, et al. Short-term effects of interferential current electromassage in adults with chronic non – specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:439–50. doi: 10.1177/0269215512460780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koldas Dogan SK, Tur BS, Kurtais Y, Atay MB. Comparison of three different approaches in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:873–81. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLoughlin TJ, Snyder AR, Brolinson PG, Pizza FX. Sensory level electrical muscle stimulation: Effect on markers of muscle injury. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:725–29. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.007401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchmuller A, Navez N, Milletre-Bernardin M, et al. Value of TENS for relief of chronic low back pain with or without radicular pain. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:656–66. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2011.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khadilkar A, Odebiyi DO, Brosseau L, Wells GA. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) versus placebo for chronic low – back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;8:CD003008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003008.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]