Abstract

We examine changes in active life expectancy in the US over 30 years, from 1982 to 2011, for white and black older adults. For older whites, longevity has increased, disability has been postponed to older ages, the locus of care has shifted from nursing facilities to community settings, and the period of disability prior to death has been compressed. However, for older blacks, longevity increases have been accompanied by smaller postponements in disability, and the percentage of remaining life spent active has remained stable and well below that of whites. Older black women were especially disadvantaged in 2011 in terms of the proportion of years expected to be lived disability-free. Public health measures directed at older blacks–particularly black women–are needed to offset impending long-term care pressures related to population aging.

INTRODUCTION

Population aging has elevated concerns about meeting the disability and long-term care needs of older adults in the US, particularly for less advantaged groups [1]. Older adults who identify as black or African American are of special interest, given that this group is the largest racial minority among older adults and is projected to nearly double by 2030 to 8.2 million from 4.5 million today [2].

Blacks who reach late life experience persistently higher disability rates, greater unmet needs for care with daily tasks, and barriers to preferred community-based sites of long-term care [1, 3-6]. Black women face especially elevated risks [7,8]. Reasons for these black-white differences are complex. For instance, relative to whites, older blacks have fewer economic resources, are more likely to be dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid and to have been uninsured and in worse health earlier in life, have higher rates of obesity and other cardiovasuclar risk factors, and have fewer social ties [9-14]. Moreover, the residential concentration of blacks in America is high and related inequities in neighorhood resources, including medical care and access to long-term care, reinforce black-white disparities [6,15].

Several studies have documented shifts in black-white disparities in late-life disability over the last few decades, but do not give a clear picture of the longer-range trend and whether it has improved over time. For example, using the National Long Term Care Survey, Manton and Gu found declines between 1982 and 1999 in age-adjusted disparities between blacks and non-blacks in moderate and severe disability and in the percentage living in an institution [4]. For the period from the late-1990s through 2006, however, National Health Interview Survey estimates by Lin and colleagues showed increases in the gap between community-based older blacks and whites in needing help with routine household activities [5].

A largely separate literature has considered changes in life expectancy of older blacks and whites. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, in 2011 life expectancy at birth for whites (79.0 years) exceeded that of blacks (75.3 years) by 3.7 years, a gap that has been narrowing gradually from a peak of 7.1 years in 1993 [16]. About one-third of this gap is attributable to differences in mortality at age 65 or later. Investigations into reasons for the continued gaps have pointed to geographic variation in socio-economic status and environmental exposures, inequitable access to medical care and public health interventions, educational differences that lead to disparities in income and wealth, and differences in chronic disease profiles [17-20].

Measures of active life expectancy combine mortality and disability rates into summary measures that are useful in assessing long-term care needs over time and across groups. Such measures convey whether survival changes are accompanied by a compression or expansion in the period spent without activity limitations (or “disability-free”). Indeed, several studies have pointed to a pattern consistent with an overall compression of morbidity through the 1980s and 1990s, particularly for those with higher educational attainment [21,22]. However, studies focused on trends in active life expectancy by race are rare. One recent exception examining a relatively short period (1999 to 2008) found a persistent gap in years of active life of about 6 years that favored whites [23].

In this study, we characterize black-white differences in both late-life mortality and disability in the U.S. and do so over a longer time frame than previously studied – from 1982 to 2011. We examine changes in the chances of survival beyond age 65 overall and without disability, the prevalence of disability, and the number and percentage of remaining years expected to be lived free from disability. We also evaluate changes in disability-free life expectancy for race and gender groups and examine years to be lived with disability by severity of limitations.

METHODS

Data

We use two data sources designed to track long-term disability trends in the US: the 1982 and 2004 National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS) screener samples and the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS). Both are nationally representative samples of adults ages 65 or older drawn from the Medicare Enrollment File and represent enrollees in all settings, including institutions.

The NLTCS was first conducted in 1982, and its sample was replenished to achieve cross-sectional representation in each of five subsequent waves through 2004, its final year [24]. The NLTCS administered a brief disability screening interview to all sample members in 1982 and repeated the screener for all sample members in 2004. Screening data are available for 19,650 respondents in 1982 and 15,993 in 2004 (response rates of 87.3% and 80.6%, respectively).

NHATS was first conducted in 2011 with 8,245 Medicare beneficiaries (response rate 70.9%; [25]). Of those, 8,077 respondents either completed the sample person interview or were living in a nursing home. A facility staff member completed a facility questionnaire for the latter group.

Measures

We used the same questions to measure activity limitations in both studies. Respondents were told: “The next few questions are about your ability to do everyday activities without help. By help, I mean either the help of another person, including the people who live with you, or the help of special equipment.” They were then asked if they had any problem without help: eating, getting in or out of bed, getting in or out of chairs, walking around inside, going outside, dressing, bathing, and getting to the bathroom or using the toilet. They also were asked if they were able to do the following activities without help: prepare meals, do laundry, do light housework, shop for groceries, manage money, take medicine, and make telephone calls. For each negative response, respondents were asked: “Does a disability or a health problem keep you from [activity]?”

We considered respondents to have a limitation if they reported a problem with (or couldn’t or didn’t do) any of the mobility or self-care activities, were unable to carry out a household activity because of disability or health, or lived in a nursing facility [26]. For analysis of active life expectancy we further defined three levels of severity: moderate disability, defined as a problem with 1-2 personal care activities or being unable to carry out any household activity; severe disability, defined as a problem carrying out 3 or more personal care activities without help; and living in a nursing facility.

The NLTCS recorded deaths through 1984, from the 1984 survey round and linkages to Medicare records, yielding a two-year mortality rate. NHATS recorded mortality during follow-up attempts in 2012 and 2013, also yielding a two-year mortality rate. We approximate one-year mortality rates in 1982 and 2011 with one-half the two-year rate calculated from each survey. Comparisons with vital statistics suggest good agreement in both years [27].

In both surveys race was self-reported and multiple race selections were allowed. From this information we identified individuals who endorsed only white (hereafter white) and those who provided any mention of black or African American (hereafter black).

Analytic Sample

Individuals who reported other races alone or in combination with white were omitted from the analytic sample. Final samples included 17,723 whites and 1,651 blacks in 1982; 14,151 whites and 1,129 blacks in 2004; and 5,801 whites and 1,825 blacks in 2011.

Statistical Methods

We calculated survival curves and life expectancy using standard abridged (5-year) life table methods [28]. To apportion life expectancy into years to be lived with and without disability we used Sullivan’s widely-used methodology [29], which divides person years expected to be lived in each age group according to the percentage in each age group with and without disability. We decomposed the change in active life expectancy for whites and blacks into changes in mortality and in the proportion of life without disability [30]. We repeated the active life expectancy analysis using the previously described measures of moderate and severe disability and for living in a nursing facility.

We also estimated active life expectancy by both race and gender. In order to have ample precision for these latter calculations, we used three ten-year age groups (65-74, 75-84, 85 and older) rather than five-year age groups. Gender-specific estimates and tests of differences over time within race and within race over time are provided in a Supplemental Appendix table [31].

We standardized disability prevalence estimates in each of the three years to the 2010 age-distribution of the white population. We calculated age-adjusted estimates of having any disability, for limitations in each individual activity, moderate and severe disability, and nursing facility residence.

We calculated estimates using survey weights that take into account differential probabilities of selection and differential non-response [32,33]. Reports of statistical significance are based on standard errors that reflect the complex designs of the surveys.

Limitations

There are two measurement-related issues for which we could not fully control, although we believe they are unlikely to account for findings. First, NLTCS screening took place largely by telephone, whereas NHATS was conducted in person. Second, the screening questions in NHATS were administered near the end of interviews, rather than at the beginning as in the NLTCS, which used the questions as a true screen to determine which respondents would proceed to a more detailed interview. A review of experimental evidence suggested that the interview mode is unlikely to have substantial effects (34), and the results of an analysis of detailed interview responses in both the NLTCS and NHATS were not consistent with significant distortion of our findings related to question placement (35).

RESULTS

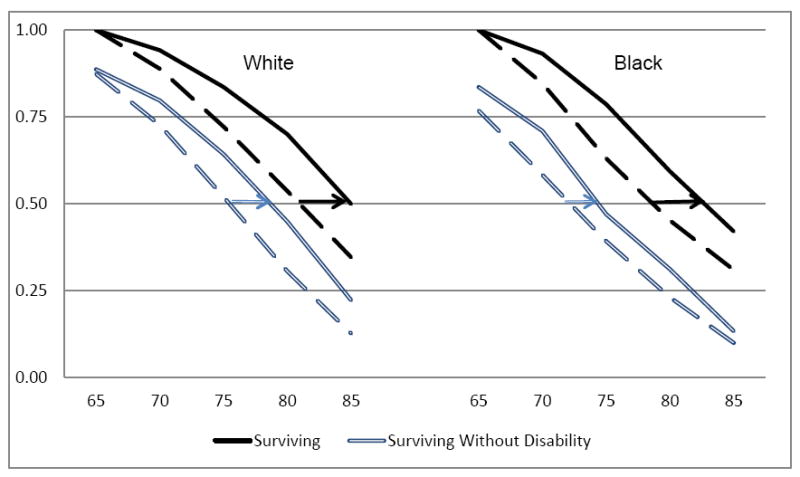

Between 1982 and 2011 expected survival beyond age 65 has improved for both whites and blacks (Exhibit 1). However, expected survival without disability has increased more for whites than for blacks. For whites, life expectancy has increased only slightly more than disability-free life expectancy, but for blacks, increases in survival have been about twice as large as increases in survival without disability.

Exhibit 1.

Overall Probability of Surviving and Probability of Surviving without Disability, US Whites and Blacks, 1982 (broken lines) and 2011 (unbroken lines).

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of the 1982 National Long Term Care Survey and the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. NOTE: Estimates conditional on surviving to age 65.

During the same period, disability prevalence declined for whites and blacks and then began to reverse course, although to varying degrees (Exhibit 2). Controlling for differences in age structure over time and between whites and blacks, the percentage of older whites living with an activity limitation fell from 1982 to 2004 by 6.7 percentage points and then rose by 2.6 percentage points from 2004 to 2011. For blacks, the improvement between 1982 and 2004 was larger–9.8 percentage points–but the reversal between 2004 and 2011 also was far larger–6.9 percentage points. As a result, the age-adjusted disability gap between whites and blacks first narrowed by 3.1 percentage points and then widened by 4.3 percentage points.

Exhibit 2.

Age-adjusted Percentages of US Whites and Blacks Ages 65 and Older with Specific Types of Activity Limitations, 1982, 2004, and 2011

|

|

White

|

Black

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tests

|

Tests

|

|||||||||||

| 1982 | 2004 | 2011 | 82 vs. 04 | 04 vs. 11 | 82 vs. 11 | 1982 | 2004 | 2011 | 82 vs. 04 | 04 vs. 11 | 82 vs. 11 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Severity | % | % | % | p | p | p | % | % | % | p | p | p |

| Any Limitation | 26.3 | 19.6 | 22.1 | *** | *** | *** | 35.0 | 25.2 | 32.1 | *** | *** | ** |

| Moderate | 12.4 | 10.1 | 12.3 | *** | *** | 19.5 | 11.4 | 17.7 | *** | *** | ||

| Severe | 6.7 | 5.8 | 6.9 | *** | *** | 10.9 | 8.7 | 10.0 | * | |||

| Nursing facility | 7.2 | 3.6 | 2.9 | *** | *** | *** | 4.6 | 5.1 | 4.4 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Personal care activity limitations | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Eating | 6.5 | 3.9 | 3.8 | *** | *** | 5.8 | 5.8 | 6.0 | ||||

| Getting in or out of bed | 8.8 | 5.5 | 6.2 | *** | ** | *** | 9.4 | 8.9 | 9.8 | |||

| Getting in or out of chairs | 9.4 | 6.4 | 6.8 | *** | *** | 9.8 | 9.4 | 11.3 | * | |||

| Walking around inside | 12.3 | 8.9 | 7.7 | *** | *** | *** | 14.8 | 12.5 | 11.4 | * | *** | |

| Going outside | 16.1 | 11.9 | 11.7 | *** | *** | 21.1 | 16.2 | 17.2 | *** | *** | ||

| Dressing | 8.8 | 5.6 | 6.8 | *** | *** | *** | 10.4 | 8.7 | 11.5 | * | *** | |

| Bathing | 11.2 | 7.3 | 7.5 | *** | *** | 13.4 | 10.4 | 12.2 | *** | |||

| Toileting | 8.2 | 5.3 | 5.2 | *** | *** | 9.6 | 8.5 | 9.4 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Household activity limitations | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Prepare meals | 11.1 | 7.3 | 7.5 | *** | *** | 14.8 | 11.6 | 13.0 | *** | * | ||

| Laundry | 13.3 | 7.9 | 8.5 | *** | *** | 18.9 | 12.8 | 15.0 | *** | * | *** | |

| Light housework | 10.4 | 6.8 | 6.6 | *** | *** | 13.5 | 11.2 | 12.8 | *** | ** | ||

| Shop for groceries | 16.8 | 10.8 | 11.2 | *** | *** | 22.8 | 15.7 | 18.1 | *** | * | *** | |

| Manage money | 10.0 | 6.7 | 7.6 | *** | ** | *** | 13.3 | 11.1 | 13.3 | ** | ** | |

| Take medicine | 8.6 | 5.9 | 6.6 | *** | * | *** | 9.9 | 9.7 | 11.4 | |||

| Make telephone calls | 9.4 | 5.5 | 4.9 | *** | * | *** | 12.6 | 8.2 | 8.2 | *** | *** | |

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of the 1982 and 2004 National Long Term Care Survey and the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study.

NOTE: Estimates adjusted to the age distribution for whites based on the 2010 US Census. Moderate is defined as limited in only household activities or 1-2 personal care activities; severe is defined as limited in 3 or more personal care activities. Personal care limitations are defined as having any problem (or can’t do or doesn’t do) an activity without help; household limitations are defined as being unable to do an activity without help because of a disability or health problem. Individuals in nursing facilities were assumed to have all limitations.

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01 for tests of difference.

Over the full 1982 to 2011 period, striking differences by race in nursing facility patterns occurred. For whites, the percentage living in such facilities declined from 7.2 to 2.9 percentage points, whereas there was little change for blacks. Moreover, whites experienced declines between 1982 and 2011 in limitations for every personal care and household activity included in the analysis, whereas blacks experienced declines only in mobility-related limitations and a few household activity limitations. Focusing on the turn-around between 2004 and 2011, fewer activities were involved for whites than for blacks. For instance, blacks but not whites experienced increases from 2004 to 2011 in being unable to do laundry, do light housework, and shop for groceries without help.

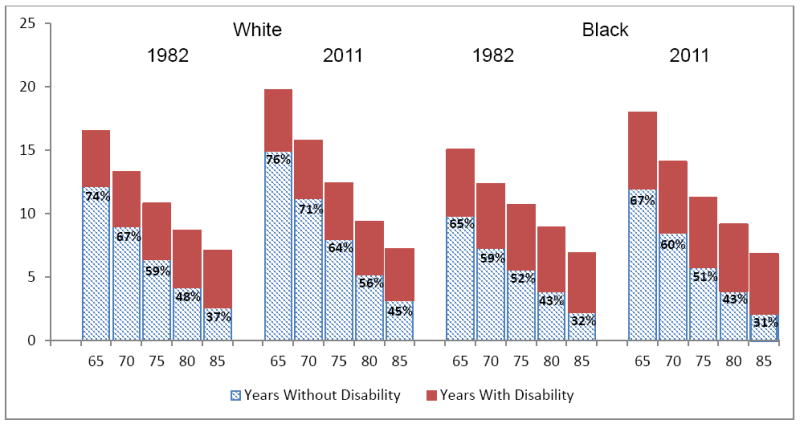

Years expected to be lived free from disability increased for both whites and blacks at age 65. For whites, disability-free years increased by 2.8 years (from 12.2 to 15.0) whereas for blacks the increase was 2.2 years (from 9.8 to 12.0) (Exhibit 3). About three-fourths of the increase in disability-free years was due to improved survival (72% for whites and 78% for blacks) and the rest of the change was accounted for by shifts in disability prevalence over the period (not shown).

Exhibit 3.

Expected Number of Remaining Years Lived with and without Disability and Percentage of Remaining Years Expected to be Lived without Disability, US Whites and Blacks, 1982 and 2011.

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of the 1982 National Long Term Care Survey and the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study.

The percentage of remaining life expected to be free from disability at age 65 was higher for whites than for blacks in both 1982 (74% vs. 65%) and 2011 (75% vs. 67%). In addition, at all ages, whites experienced increases in the percentage of years expected to be lived free from limitations, and this compression increased with age, whereas blacks experienced no such gains.

Analyses stratified by gender [31] suggest racial gaps for both men and women in the number of years expected to be disability-free in 1982 and 2011. Moreover, the number of disability-free years expected to be lived at age 65 increased for whites and for black men but not for black women. The percentage of remaining life expected to be active at age 65 increased significantly only for white males, who reached nearly 82% in 2011. In contrast, at age 65, black women could expect 62% of remaining years to be disability-free in 2011, which was 9 percentage points lower than white women and 12 percentage points lower than black men in that year. Similarly, at age 85, the percentage of life disability-free improved only for white men to 62% in 2011; in that year, black women could expect only one-quarter of remaining years to be disability-free.

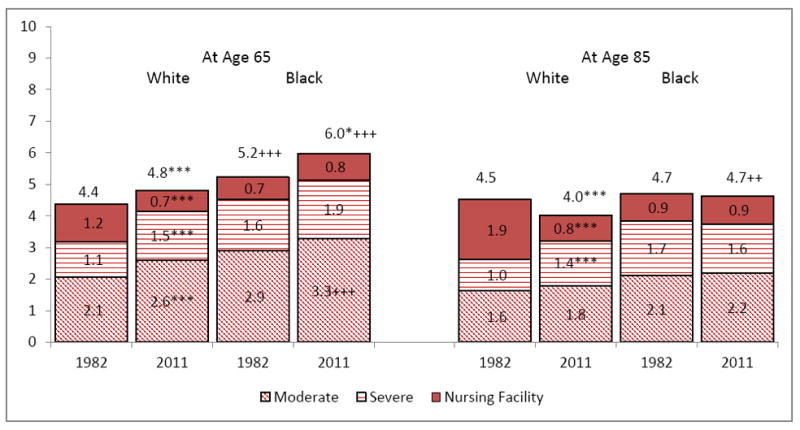

The expected number of remaining years to be lived with disability at age 65 increased for whites and blacks by .4 and .8 years, respectively (Exhibit 4). For whites, years expected to be lived with moderate and severe disability increased, but the number to be lived in a nursing facility fell. At age 85, expected number of years to be lived with disability declined by .5 years for whites but not blacks and was accompanied by a shift in expected years lived in nursing facilities to other care settings.

Exhibit 4.

Expected Number of Remaining Years Lived with Disability at age 65 and 85 by Severity, US Whites and Blacks, 1982 and 2011.

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of the 1982 National Long Term Care Survey and the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. NOTE: * p<.10 **p<.05 ***p<.01 for test of difference from 1982 (same race); + p<.10 ++p<.05 +++ p<.01 for test of difference from white (same year).

DISCUSSION

Older blacks and whites in the US have experienced different disability patterns over the last 30 years as longevity has increased. For older whites, disability has been postponed to older ages and the period of disability prior to death has been compressed. However, for older blacks, longevity increases have been accompanied by smaller postponements in disability, and the proportion of remaining life to be spent active has remained stable at about two-thirds at age 65 and one-third at age 85, well below that of whites.

These findings add to existing studies focused on whether there has been a compression of morbidity in the US. Largely due to data constraints, prior studies have focused on shorter (generally 10- or 20-year) time periods and have not emphasized race. On balance our findings are consistent with prior studies, which have found compression of disability at age 65 during the 1980s and 1990s [22]. By focusing on racial differences, however, we find that the compression – defined as an increase in the percentage of remaining life to be lived without disability – has been experienced by whites but not blacks at older ages. We further demonstrate that for both groups the increases from the early 1980s in active years have been driven largely by declines in mortality and not by shifts in disability.

Our analysis also suggests that the black-white gaps persisted in large part because of the lack of progress for older black women in gaining years of active life. This finding is consistent with prior research demonstrating that black women experience a unique disability trajectory in later life that reflects accelerated impairment at older ages [8]. We add to this literature by pointing out that in the aggregate black women have not experienced the gains seen for other groups over the last thirty years in either the number of years of active life or percentage of life expected to be active.

A few additional encouraging findings also emerged, but were limited to whites. For that group, we found a dramatic change in the locus of care from nursing facilities to community settings and, at age 85, declines in expected years lived with disability. Whites and blacks also experienced an increase in the number of years expected to be lived disability-free at age 65; but, for blacks the percentage of years expected to be disability-free remained stable and below that of whites at all ages. Moreover, unlike whites, their expected number of years to be lived with disability at age 85 did not decline over this period.

The stagnation for blacks may be linked in part to the reversal in several activity limitations especially important for living in the community – that is, the ability to do laundry, do light housework and to shop without help. Blacks also experienced no change in the rate of nursing facility use. The finding of differential reductions in nursing home use for blacks and whites in the aggregate mirror increased use of assisted living and community-based care alternatives by whites over this period [6, 36]. This trend is particularly concerning because of previously documented racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care as well as the high public cost associated with nursing facility use [36, 37]. Moreover, the finding underscores the need for policies that address continued disparities by race in access to preferred community alternatives [6].

Because we have only three cross-sectional sets of consistent measures, we could not examine the role of disability onset and recovery in changes in active life expectancy or turning points for changes in disability prevalence. That said, we found that mortality shifts were more important than disability for estimated changes in active life expectancy, and other studies have provided evidence that the early 2000s was the time period when previously downward trends in the prevalence in moderate disability flattened or reversed [38].

Our findings highlight the need for health policies and public health interventions that might further improve functioning and reduce long-term care needs of the older population in the US, particularly for blacks. Indeed, the existing health care delivery and financing system was not set up to promote optimal functioning, but instead to focus on treatment, and to some degree more recently, prevention of disease. For example, assistive devices, home modifications, and home safety programs have traditionally been covered by Medicare or Medicaid only in limited circumstances, and they do not historically fall under the purview of physicians but instead require coordination with physical and other therapists and social services. Consequently, for many years, options to make home environments more supportive often have not been accessible to less advantaged segments of the older population who are at elevated risk for developing disability.

Recently, a number of innovations aimed at improving the quality of care for the older population have been occurring in both the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Spurred in part by provisions of the Affordable Care Act, new value-based payment structures and new models for integrated whole-person care to improve management of chronic conditions and coordination of health, behavioral, and supportive services are being implemented [39]. For those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, there is an enhanced focus on integrating service delivery by the two programs to improve access to and coordination of supportive, social, and medical services for older adults with complex medical and functional needs. The extent to which reforms will expand access to functioning-related assistance remains to be seen. Continued monitoring of disparities in active life expectancy in the wake of these reforms is an important task.

Focusing on new payment incentives and delivery system reforms alone, however, is unlikely to spur sufficient improvements to substantially close the gap for older blacks. This is especially true for black women, who lag behind other groups in both the years and percentage of life expected to be lived free from disability. Some have argued that to narrow racial health disparities both individual behavior and community-level barriers to improvement should be targeted and that not only health-related but also social and economic factors need be addressed [15,40]. Several studies have argued that targeting contributing factors that have their roots much earlier in life are needed to address disparities in late-life disability such as those documented here [41,42]. Our findings suggest that pinpointing which measures would be most effective in reducing dependence among older blacks–particulary older black women–is necessary and likely to be an important step toward offsetting impending long-term care pressures related to population aging.

Conclusions

Over the last 30 years the period of disability prior to death has been compressed for older whites. For older blacks, the percentage of remaining life spent active has remained stable and well below that of whites. Black women are especially disadvantaged since they had no gains in either the expected number or proportion of remaining years to be spent disability-free. Given that the Baby Boom generation’s long-term care demands are expected to peak in 2030, our findings support continued close monitoring of the needs of older adults and the efficacy of health system reforms in meeting them. In the shorter run, improvements in medical, social, and support services may be able to affect functioning and health trajectories, quality of life, and costs of care for all older persons. In the longer run, additional policies to ameliorate root causes earlier in life–particularly those that disadvantage black women–also may be needed to reduce late-life disparities in active life that have persisted over three decades.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the National Institute on Aging U01-AG032947. The views expressed are those of the authors alone and do not represent those of their employers or funding agency.

Contributor Information

Vicki A. Freedman, University of Michigan

Brenda C. Spillman, Urban Institute

References

- 1.Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Disability and Care Needs Among Older Americans. Milbank Q. 2014;92(3):509–541. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Projected Population by Single Year of Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States: 2014 to 2060. [August 18, 2015];US Census Bureau, Population Division Release date: December 2014. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/downloadablefiles.html.

- 3.Schoeni RF, Martin LG, Andreski PM, Freedman VA. Persistent and growing socioeconomic disparities in disability among the elderly: 1982-2002. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(11):2065–2070. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manton KG, Gu X. Changes in the prevalence of chronic disability in the United States black and nonblack population above age 65 from 1982 to 1999. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 May 22;98(11):6354–6359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111152298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin S, Beck AN, Finch BK, Hummer RA, Master RK. Trends in US Older Adult Disability: Exploring Age, Period, and Cohort Effects. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:2157–2163. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng Z, Fennell ML, Tyler DA, Clark M, Mor V. Growth Of Racial And Ethnic Minorities In US Nursing Homes Driven By Demographics And Possible Disparities In Options. Health Affairs. 2011;30(7):1358–1365. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warner DF, Brown TH. Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age-trajectories of disability: an intersectionality approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(8):1236–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendes de Leon CF, Barnes LL, Bienias JL, Skarupski KA, Evans DA. Racial disparities in disability: recent evidence from self-reported and performance-based disability measures in a population-based study of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005 Sep;60(5):S263–71. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.5.s263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Social Security Administration. [August 27, 2015];Income of the Population 55 or Older, 2012. Available at http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/income_pop55/2012/incpop12.pdf.

- 10.Congressional Budget Office. [Septemer 2, 2015];Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries of Medicare and Medicaid: Characteristics, Health Care Spending, and Evolving Policies. 2013 Available at https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/44308_DualEligibles2.pdf.

- 11.Kirby JB, Kaneda T. Unhealthy and Uninsured: Exploring Racial Differences in Health and Health Insurance Coverage Using a Life Table Approach. Demography. 2010;47(4):1035–51. doi: 10.1007/BF03213738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alley DE, Chang VW. The Changing Relationship of Obesity and Disability, 1988-2004. JAMA. 2007;298(7):2020–2027. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005 Mar 15;111(10):1233–41. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Bienias JL, Evans DA. A longitudinal study of black-white differences in social resources. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004 May;59(3):S146–53. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.s146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social Sources of Racial Disparities In Health. Health Affairs. 2005;24(2):325–334. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ. National vital statistics reports. 3. Vol. 63. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Deaths: Final data for 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper S, MacLehose RF, Kaufman JS. Trends in the black-white life expectancy gap among US states, 1990-2009. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014 Aug;33(8):1375–82. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullen MR, Cummins C, Fuchs VR. Geographic and racial variation in premature mortality in the U.S.: analyzing the disparities. PloS One. 2012;7(4):e32930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elo IT, Beltrán-Sánchez H, Macinko J. The Contribution of Health Care and Other Interventions to Black-White Disparities in Life Expectancy, 1980-2007. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2014 Feb 1;33(1):97–126. doi: 10.1007/s11113-013-9309-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Bascardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of Major Diseases to Disparities in Mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1585–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crimmins EM, Zhang Y, Saito Y. Trends over 4 decades in disability-free life expectancy in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(7):1287–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freedman VA, Wolf DA, Spillman BC. Disability-free life expectancy over 30 years: A growing female disadvantage in the US population. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(6):1079–85. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molla MT Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Expected years of life free of chronic condition-induced activity limitations – United States, 1999-2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manton KG. ICPSR09681-v5. Ann Arbor: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2010. National Long-Term Care Survey: 1982, 1984, 1989, 1994, 1999, and 2004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasper JD, Freedman VA. National Health and Aging Trends Study Round 1 User Guide: Final Release. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2012. [July 25, 2015]. http://nhats.org/scripts/documents/NHATS_Round_1_User_Guide_Final_Release.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Respondents living in nursing facilities did not receive the disability screening questions in either the NLTCS or NHATS.

- 27.Available for 1982 and 2011 at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsus/VSUS_1982_2A.pdf and http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr63/nvsr63_03.pdf

- 28.Arias E. National vital statistics reports. 7. Vol. 63. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. [July 25, 2015]. United States life tables, 2010. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr63/nvsr63_07.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jagger C, Cox B, Le Roy S EHEMU. EHEMU Technical Report. Third Edition. 2006. Health Expectancy Calculation by the Sullivan Method. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nusselder WJ, Looman CWN. Decomposition of differences in health expectancy by cause. Demography. 2004;41:315–334. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.See Exhibit A1.

- 32.U.S. Census Bureau. Weighting Specifications for the Long Term Care Survey. Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 1982. [May 10, 2015]. http://www.nltcs.aas.duke.edu/pdf/82_CrossSectionalWeights.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Kasper JD. NHATS Technical Paper #2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2012. [July 25, 2015]. National Health and Aging Trends Study Development of Round 1 Survey Weights. http://nhats.org/scripts/documents/NHATS_Round1_WeightingDescription_Nov2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Leeuw E. To Mix or Not to Mix Data Collection Modes in Surveys. Journal of Official Statistics. 2005;21:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- 35.We hypothesized that if placement at the end of the NHATS interview led to inflated affirmative reports, we would observe that those meeting screening criteria in 2011 had less severe disability levels (for example fewer reports of assistance) than those meeting screen in criteria in 1982 and 2004. We found no such pattern.

- 36.Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno JM, Miller SC. Driven to Tiers: Socioeconomic and Racial Disparities in the Quality of Nursing Home Care. Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(2):227–256. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stewart KA, Grabowski DC, Lakdawalla DN. Annual expenditures for nursing home care: Private and public payer price growth, 1977–2004. Medical Care. 2009;47(3):295–301. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181893f8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Andreski PM, Cornman JC, Crimmins EM, Kramarow E, et al. Trends in Late-Life Activity Limitations: An Update from 5 National Surveys. Demography. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0167-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abrams M, Nuzum R, Zezza M, Ryan J, Kiszla J, Guterman S. The Affordable Care Act’s Payment and Delivery System Reforms: A Progress Report at Five Years. [August 27, 2015];Commonwealth Fund pub 1816. 2015 Available at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/may/aca-payment-and-delivery-system-reforms-at-5-years. [PubMed]

- 40.Haas SA, Krueger PM, Rohlfsen L. Race/ethnic and nativity disparities in later life physical performance: the role of health and socioeconomic status over the life course. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012 Mar;67(2):238–48. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.August KJ, Sorkin DH. Racial and ethnic disparities in indicators of physical health status: do they still exist throughout late life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010 Oct;58(10):2009–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. [August 27, 2015]. Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43943/1/9789241563703_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.