Abstract

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia. The search for new treatments is made more urgent given its increasing prevalence resulting from the aging of the global population. Over the past 20 years, stem cell technologies have become an increasingly attractive option to both study and potentially treat neurodegenerative diseases. Several investigators reported a beneficial effect of different types of stem or progenitor cells on the pathology and cognitive function in AD models. Mouse models are one of the most important research tools for finding new treatment for AD. We aimed to explore the possible therapeutic potential of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell xenografts in a transgenic (Tg) mouse model of AD.

Methods

APP/PS1 Tg AD model mice received human umbilical cord stem cells, directly injected into the carotid artery. To test the efficacy of the umbilical cord stem cells in this AD model, behavioral tasks (sensorimotor and cognitive tests) and immunohistochemical quantitation of the pathology was performed.

Results

Treatment of the APP/PS1 AD model mice, with human umbilical cord stem cells, produced a reduction of the amyloid beta burden in the cortex and the hippocampus which correlated with a reduction of the cognitive loss.

Conclusion

Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells appear to reduce AD pathology in a transgenic mouse model as documented by a reduction of the amyloid plaque burden compared to controls. This amelioration of pathology correlates with improvements on cognitive and sensorimotor tasks.

Keywords: Alzheimer, Stem Cell, Behavior, Histology, Animal Model, Amyloid Beta

INTRODUCTION

Globally more than 47 million people suffer from dementia, with the likelihood that this number will greatly increase in the coming years [1]. Of all neurodegenerative disorders, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent. The current global cost of care for AD is approximately $605 billion, or about 1% of the entire world’s gross domestic product. AD is a neurodegenerative disease defined in the brain by pathological accumulation of amyloid β (Aβ) into extracellular plaques in the brain parenchyma and in the vasculature (known as congophilic amyloid angiopathy [CAA]), and abnormally phosphorylated tau that accumulates intraneuronally forming neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs); lesions are associated with neuronal loss in specific brain regions [2]. Currently there are no effective means to treat or slow down the pathology of AD; although, there are a number of potential therapies in preclinical development and in clinical trials [3]. In recent years, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been considered a promising therapeutic strategy for both acute injury and progressive degenerative diseases of the central nervous system [4–8]. It has been proposed that stem cell therapies can replace lost cells by differentiating into functional neural tissue; modulate the immune system to prevent further neurodegeneration and effect repair or provide trophic support for the diseased central nervous system (CNS) [7, 8]. Moreover, MSCs greatly enhance autolysosome formation and clearance of Aβ in AD models, which may lead to increased neuronal survival in the setting of Aβ pathology [9]. MSCs have also been shown to be protective against cell death induced by misfolded tau protein [5]. One source of stems cells is human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells (hUCB-MSCs). In this study, we tested the efficacy of hUCB-MSCs tested the efficacy of hUCB-MSCs in an APP/PS1AD mouse model using an intra-carotid route, following injection of mannitol to transiently open the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animal Model

All the procedures were done according to the guidelines of the institutional animal care committee of NYU School of Medicine. The AD animal model used in this study was a well characterized double transgenic mouse line expressing mutated APP and PS1 [10]. The mice were used at 9–10 months of age a point at which they have extensive amyloid deposition. All the mice were females. Animals were divided into 2 groups. Five animals served as controls and 5 received human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs) by intra-carotid artery, immediately following a 200 μl injection of 20% mannitol in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) to transiently open the BBB, as we have previously published [11, 12].

Stem Cell Preparation

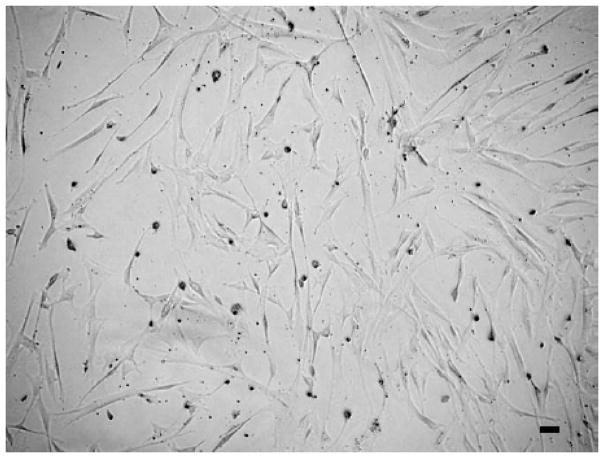

Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC® PCS500010™, Manassas City, VA, USA), together with their growth-supporting media, growth factors, enzymes and antibiotics. The cells were prepared and sub-cultured according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and procedures. Cells from the 5th and 6th passage were utilized for injection. Cells were suspended in 0.5 ml of PBS (GIBCO Invitrogen Corporation, Cat# 14190-094, United Kingdom) at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml. 5 × 105 cells were injected. The morphology of the injected hUCB-MSCs is shown in Fig. (1).

Fig. (1).

Shows representative morphology of the human umbilical cord Stem cells obtained at the 5 passage. These stem cells were injected via the carotid artery after mannitol infusion to transiently open the blood brain barrier. (Magnification 10X and Scale bar = 25μm).

ANIMAL BEHAVIOR ASSESSMENTS

Sensorimotor Tests

Rotarod

Animals were placed onto the rod to measure forelimb and hindlimb motor coordination and balance. The trials were conducted as previously published [13, 14].

Locomotor Activity

A Hamelton-Kinder photobeam system was used to measure the activity of the animals. A video camera recorded the horizontal movements on the circular open field chamber (75 × 75 cm). Each animal were tested for 15 minutes, the total distance (cm), the mean resting time and the velocity (mean and maximum) were recorded, as previously published [13, 14].

Cognitive Test

Object Recognition

The object recognition test was used to measure changes in short term memory. This was done by allowing the mice to explore a square-shaped open field box (48 cm square, 18 cm high) with two novel objects at diagonal corners. The time was recorded via a tracking system. After 3 hours upon which retention delay occurs, the mice were placed into the box with a novel object placed. The duration to explore the novel object is 6 minutes. The percentage short term memory score is calculated as previously published [13, 14].

Immunohistochemistry

The right hemisphere was immersion-fixed overnight in periodate-lysine-paraform-aldehyde. Following fixation, the brain was moved to a phosphate buffer solution containing 20% glycerol and 2% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at 4°C until sectioned. Serial coronal brain sections (40 μm) were, placed in ethylene glycol cryo-protectant and stored at −20°C until they were used. Sections were immunolabeled with a monoclonal anti-Aβ antibody 6E10 as previously described [13, 14]. To detect the presence of the human stem cells in the mouse brains, the sections were immunolabeled with a mouse monoclonal antibody to human nuclear antigen (Cat. No.: NBP2-34342, Novus Biologicals) that is specific for human cells. To examine the brain inflammation levels of treated mice, we assessed the degree of astrocytosis and microgliosis with GFAP and Iba-1 antibodies respectively. Astrogliosis and microgliosis were analyzed at 10X magnifications in the cortex and in the hippocampus. Reactive astrocytosis was rated on a scale from 0 to 4. The rating for astrogliosis was based on the extent of GFAP immunoreactivity (number of GFAP immunoreactive cells and complexity of astrocytic branching) as previously published [14]. The assessment of microgliosis was based on the extent of immunoreactivity with Iba-1 antibody. Rating with rating from 0 (few resting microglia) to 4 (numerous ramified/phagocytic microglia) in increments of 0.5. The rating was done by an observer blinded to the treatment status of the mice [14]. The images of the immunostained tissue sections with the monoclonal antibody 6E10 were acquired by Nikon Eclipse E Fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) and processed by NIS elements for advanced research, with the input levels adjusted to span the range of acquired signal intensities. Total Aβ burden (defined as the percentage of test area occupied by Aβ) was quantified for the cortex and for the hippocampus on coronal plane sections stained with the monoclonal antibodies 6E10. For each mouse five adjacent sections were selected, and from each section 5 random fields were analyzed. Total area of pixel intensity was measured with the automated measurements tools in NIS Elements software. The total intensity was averaged and expressed as normalized, corrected values. All procedures were performed by an individual blinded to the experimental condition of the study [14].

RESULTS

Behavioral studies (Rotarod, Locomotor Activity and Object Recognition)

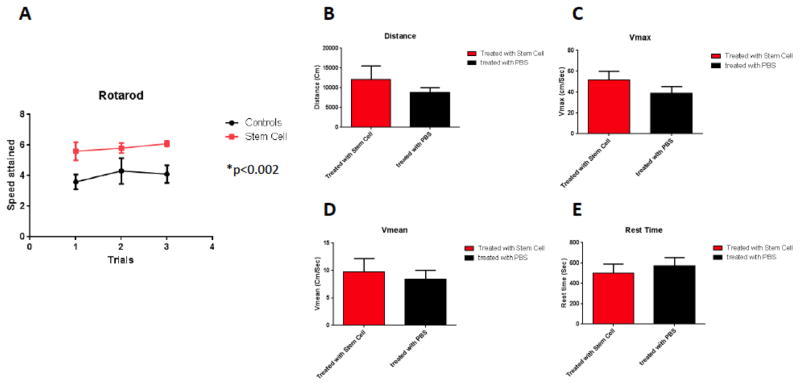

One month following the injection of hUCB-MSCs, the mice were subjected to behavioral testing (sensorimotor and cognitive tasks). On rotarod testing, treated animals navigated better than controls which received only PBS (p=0.0024, by two-tailed student’s t-test) Fig. (2A). On locomotor activity testing no significant differences were seen between the two groups in terms of the distance traveled (Fig. 2B), Vmax (Fig. 2C), Vmean (Fig. 2D) or in rest time (Fig. 2E).

Fig. (2).

Rotarod: A significant difference was observed between controls (n=5) and treated mice with stem cells (n=5) (Two tailed t-test, p=0.0024) (Fig. 2A). Locomotor activity: No significant difference was observed between treated animals and controls in their distance traveled (Fig. 2B), maximum velocity (Fig. 2C), Average speed (Fig. 2D) or resting time (Fig. 2E).

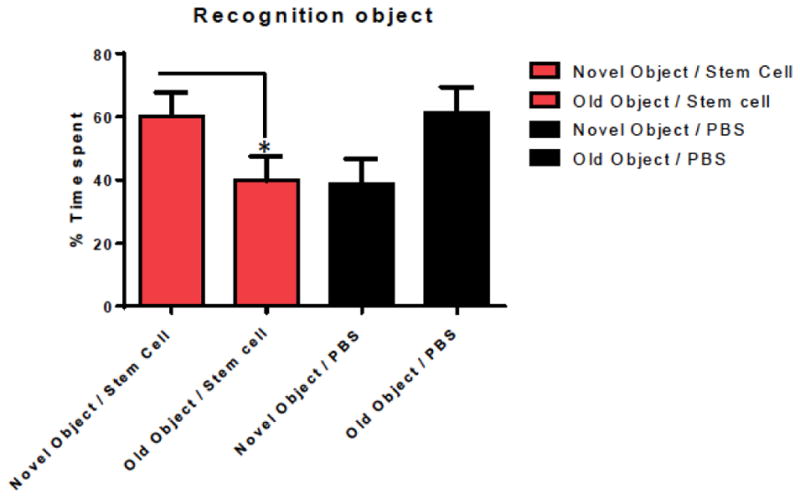

In addition to locomotor evaluations, the two groups of mice underwent cognitive testing using the Novel Object Recognition test. Mice treated with hUC-MSCs spent more time with the novel object compared to that of the old object (Fig. 3, one tailed t-test, p= 0.0463, comparing first and second bars). The time spend with the novel object differed significantly between the of hUCB-MSCs treated and control Tg groups (Fig. 3, one-tailed t-test, p=0.0427, comparing first and third bars).

Fig. (3).

Shows working memory improvement using a short term memory test (Novel Object Recognition Test). The bars depict the percentage of amount of time spend with the novel or old object. Mice treated with hUC-stem cells spent more time with the novel object compared to the old object (one tailed t-test, p= 0.0463). The time spend with the novel object differed significantly between the stem cell treated and control Tg groups (n=5 per group) (one-tailed t-test, p=0.0427).

Histology

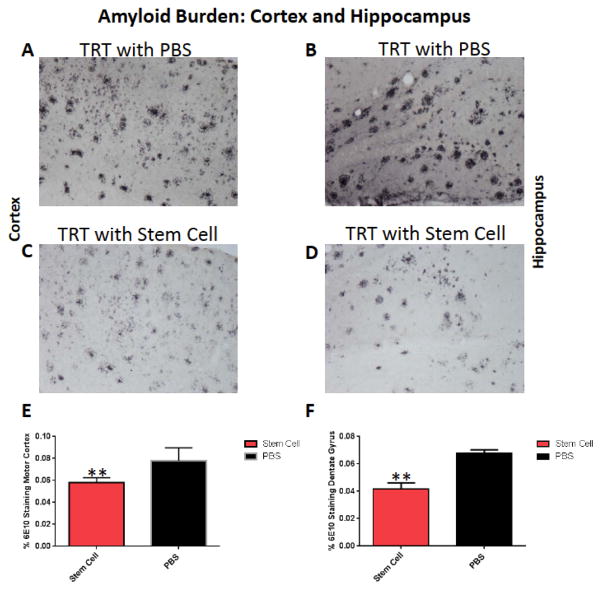

After the behavioral tasks, both groups were sacrificed at 10 to 11 months of age and the brains were extracted and further processed for histology. Morphological analysis showed that treated animals had fewer plaques than controls receiving only PBS as detected by 6E10. To determine the efficacy of stem cell therapy in the APP/PS1 Tg mouse model, the total amyloid burden was quantified by stereological technique using random unbiased sampling in the serial sections. The amyloid burden is shown in the cortex and hippocampus in Fig. (4). Significant reduction of the amyloid burden was observed in the total cortex by 26% (two tailed t-test, p=0.0084) and in the hippocampus by 38% (two tailed t-test, p=0.0011).

Fig. (4).

Shows representative brain sections from both group (n=5 per group) showing Aβ immunostaining in the cortex (A and C) and in the hippocampus (B and D) in PBS treated mice (A and B) and hUC-stem cells treated animal (C and D). A significant reduction of the amyloid burden was observed in the cortex by 26% (E, two tailed t-test, p=0.0084) and in the hippocampus by 38% (F, two tailed t-test, p= 0.0011).

Astrogliosis

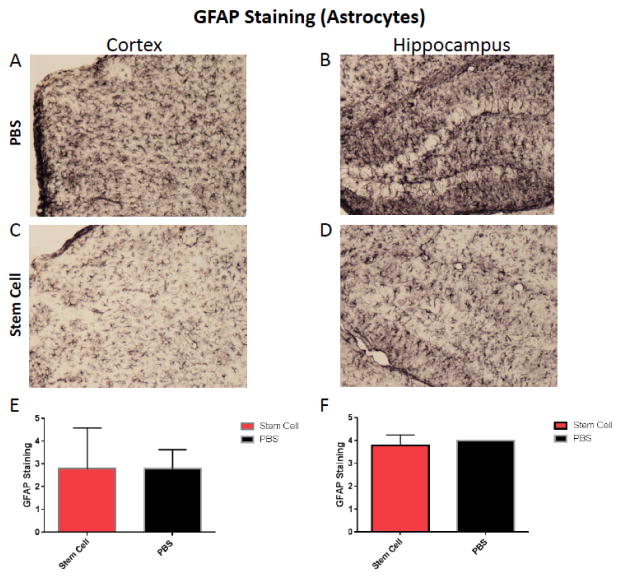

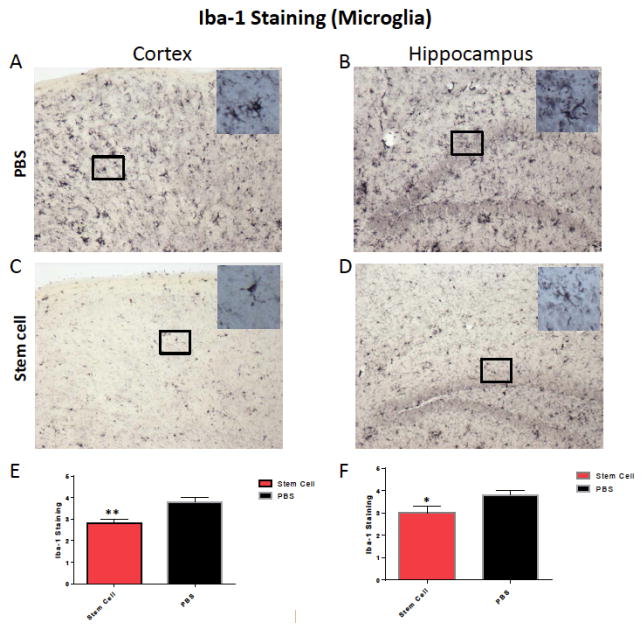

To evaluate the effect of stem cells on brain inflammation, serial sections were stained with GFAP and Iba-1 antibodies. Semi–quantitative analysis of astrocytes (GFAP immunolabeling) didn’t show a significant difference between both treated and untreated groups (Fig. 5). Reduction or activation of astrocytes in treated animals versus controls was not statistically significant. However, a significant difference were observed with microglia immunoreactivity in the cortex and hippocampus of treated animals versus controls, respectively (one tailed Mann-Whitney test p=0.0011 and p=0.042 in the cortex and hippocampus, respectively, Fig. 6).

Fig. (5).

Shows representative brain sections from both group showing GFAP immunostaining in the cortex (A and C) and in the hippocampus (B and D) in PBS treated mice (n=5) (A and B) and hUC-stem cells treated animal (n=5) (C and D). Semi-quantitative analysis of the GFAP immunoreactivity did not show any significant difference in the cortex (E) or hippocampus (F).

Fig. (6).

Shows representative brain sections from both groups (n=5 per group) showing microglia immunostaining in the cortex (A and C) and in the hippocampus (B and D) in PBS treated mice (A and B) and hUC-stem cells treated animal (C and D). Semi-quantitative analysis of the microglia immunoreactivity shows a significant difference in the cortex (E, one tailed Mann-Whitney test p=0.0011) and in the hippocampus (F, one tailed Mann-Whitney test p=0.042).

Assessment for the presence of hUCB-MSCs in the Brain

To assess for the presence of the human stem cells in the mouse brains, the sections were immunolabeled with a mouse monoclonal antibody to human nuclear antigen (Cat. No.: NBP2-34342, Novus Biologicals) that is specific for human cells. Immunolabeled cells were detected scattered throughout the brain of all hUCB-MSCs injected mice, while in control mice no immunolabeled cells could be detected (Fig. 7).

Fig. (7).

Shows an immunolabeled brain section of the cortex using a monoclonal antibody to human nuclear antigen, specific for human cells (Cat. No.: NBP2-34342, Novus Biologicals). Scattered hUCB-MSCs were detected in treated animals throughout the brain and were absent in the control animals. (Scale bar = 25μm).

DISCUSSION

Neurodegenerative diseases create a tremendous social burden due to their devastating nature, cost, and lack of effective therapies. There are many ongoing clinical trials to treat Alzheimer’s disease; however, so far the results of these clinical trials has been disappointing [15]. Cellular therapies offer great promise for the treatment of these diseases, and research progress to date supports the utilization of stem cells to offer cellular replacement and/or provide environmental enrichment to attenuate neurodegeneration [4–8]. In diseases where specific subpopulations of cells or widespread neuronal loss are present, cellular replacement may reproduce or stabilize neuronal networks. In addition, environmental enrichment may provide neurotrophic support to remaining cells or prevent the production or accumulation of toxic factors that harm neurons. Bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) have great potential as therapeutic agents since they are easily obtained from bone marrow and can be expanded rapidly ex vivo for autologous transplantation. They are allogeneic and non-immunogenic, thus eliminating the risk of rejection [16]. The potential of BM-MSCs in the treatment of AD was shown in an acute AD mouse model, where the intracerebral transplantation of BM-MSCs promoted the reduction of Aβ through the microglial activation [17]. This AD model consisted of the acute injection of Aβ peptide into the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus in wild-type C57BL/6 mice. It was also suggested that BM-MSCs can ameliorate Aβ-induced neurotoxicity and cognitive decline by inhibiting apoptotic cell death and oxidative stress in the hippocampus [18] The intracerebral transplantation of BM-MSCs into amyloid precursor protein (APP)/presenilin 1 (PS1) double-transgenic AD model mice modulated the immune/inflammatory responses resulting in a reduction of pathology and improvements in the cognitive decline [19]. It has also been shown that BM-MSC injected to the tail vein of the AD model rats not only migrate through the blood–brain barrier, but survive in the hippocampus with associated cognitive benefits [20]. Single intra-cerebral injection of BM-MSCs produced an acute reduction in Aβ deposits and facilitated changes in key proteins required for synaptic transmission in young AD mice [21].

Another source of stem cells is human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells (hUCB-MSCs). It has been shown that co-culture of hUCB-MSCs with BV2 microglia exposed to Aβ42 induced a reduction of the Aβ in the medium in association with an increased expression of the Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin (NEP) in the microglia [22]. When hUCB-MSCs were transplanted into the hippocampus of a 10-month-old transgenic mouse model of AD (with extensive pathology) for 10, 20, or 40 days, NEP expression was increased in the mice brains, in association with increased production of soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM) [22]. Moreover, Aβ plaques in the hippocampus and other brain regions were decreased associated with active migration of hUCB-MSCs toward Aβ deposits. This data suggests that hUCB-MSC-derived sICAM-1 decreases Aβ plaques by inducing NEP expression in microglia through the sICAM-1/LFA-1 signaling pathway. Injecting hUCB-MSCs by intracerebral cannula into the hippocampus of APP/PS1 AD model transgenic mice resulted in a significant improvement of spatial learning and memory [23]. These investigators also reported a reduction in tau hyperphosphorylation. The effects were associated with reversal of disease-associated microglial neuroinflammation, as evidenced by decreased microglia-induced proinflammatory cytokines, elevated alternatively activated microglia and increased anti-inflammatory cytokines. They concluded that hUCB-MSCs exerted a neuroprotective effect through modulation of microglial activation state, thereby ameliorating disease pathophysiology and reversing the cognitive decline associated with amyloid deposition in AD mice. hUCB-MSCs have proven to be more beneficial than bone marrow-derived MSCs in term of cell procurement, storage and transplantation [24].

For stem cell delivery to the brain, systemic administration is preferable. Intracranial stem cell delivery may be associated with side effects such as bleeding and local tissue injury. However, systemic injection requires overcoming the blood brain barrier (BBB) in order to achieve adequate entry of stem cells into the CNS. Mannitol injection has been extensively used to transiently open the BBB and has also been shown to enhance delivery of stem cells to the brain [11, 25]. In our study, we used this method to open the BBB, followed immediately by injection of 1 × 105 hUC-MSCs via the carotid artery. After one month, sensorimotor and cognitive tasks were performed. Significant difference was observed with rotarod testing, where treated animals navigated better than controls that received PBS only, suggesting an improvement in the coordination of treated mice. Importantly, locomotor activity testing did not show any significant differences between the groups, suggesting that basic locomotor function and the state of alertness was similar in both groups. The presence of differences in locomotor activity could confound the interpretation of cognitive testing. On novel object recognition testing we found that the hUC-MSCs treatment led to a significant cognitive improvement. Furthermore, the quantification of the amyloid burden performed on serial brain sections by immunohistochemistry shows a reduction of the amyloid burden in the cortex and the hippocampus of treated animals. The histopathology results correlated with the effect observed in the object recognition test. There was no evidence of inflammatory toxicity with the use of the hUC-MSCs as judged by GFAP immunoreactivity, which showed no significant differences between treated and control Tg mice. Whereas, significant difference were observed with microglia immunoreactivity in the cortex and in the hippocampus of treated versus controls. Recently, similar data obtained by systemic transplantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in an AD mouse model were reported, supporting our findings [26].

The mechanisms involved are unclear, but there are a number of non-mutually exclusive possibilities. It has been reported that hUCB-MSCs secrete high levels of sICAM-1, which induces NEP expression, a key Aβ-degrading enzyme in microglia. Furthermore, hUCB-MSC-derived sICAM-1 interrupted the CD40/CD40L interaction on microglia through down regulation of CD40 expression in microglia [22]. It has also been reported that galectin-3 secreted by hUCB-MSCs protects against Aβ42 neurotoxicity [22]. Finally, hUCB-MSCs may participate simultaneously in Aβ clearance and neuronal survival through a paracrine mechanism in the AD microenvironment [22].

Our results suggest that a single application of hUC-MSCs administered by a systemic route are a promising therapy that can modulate the CNS environment to ameliorate AD related pathology and its associated cognitive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, awarded to Abdelwahab Noorwali and Hazem Atta. This work was also supported by NIH grants AG20245 and NS73502 (TW) and SACM (AB). The authors would like to thank Drs: Abdulaziz Awwad and Ismail Almokyad for their valuable help.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

Send Orders for Reprints to reprints@benthamscience.ae

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’ Association Report. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015;11:332–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, Bouras C, Braak H, Cairns N, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:362–81. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31825018f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wisniewski T, Goni F. Immunotherapeutic Approaches for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron. 2015;85:1162–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HJ, Lee JK, Lee H, Shin JW, Carter JE, Sakamoto T, et al. The therapeutic potential of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2010;481(1):30–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zilka N, Zilkova M, Kazmerova Z, Sarissky M, Cigankova V, Novak M. Mesenchymal stem cells rescue the Alzheimer’s disease cell model from cell death induced by misfolded truncated tau. Neuroscience. 2011;193:330–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Si YL, Zhao YL, Hao HJ, Fu XB, Han WD. MSCs: Biological characteristics, clinical applications and their outstanding concerns. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(1):93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan X, Sun D, Tang X, Cai Y, Yin ZQ, Xu H. Stem-cell challenges in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a long way from bench to bedside. Med Res Rev. 2014;34(5):957–78. doi: 10.1002/med.21309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turgeman G. The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in Alzheimer’s disease: converging mechanisms. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10(5):698–9. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.156953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin JY, Park HJ, Kim HN, Oh SH, Bae JS, Ha HJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance autophagy and increase beta-amyloid clearance in Alzheimer disease models. Autophagy. 2014;10(1):32–44. doi: 10.4161/auto.26508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holcomb L, Gordon MN, McGowan E, Yu X, Benkovic S, Jantzen P, et al. Accelerated Alzheimer-type phenotype in transgenic mice carrying both mutant amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 transgenes. Nat Med. 1998;4(1):97–100. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J, Zaim Wadghiri Y, Hoang DM, Tsui W, Sun Y, Chung E, et al. Detection of amyloid plaques targeted by USPIO-Aβ1-42 in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice using magnetic resonance microimaging. Neuroimage. 2011;55:1600–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigurdsson EM, Wadghiri YZ, Mosconi L, Blind JA, Knudsen E, Asuni A, et al. A non-toxic ligand for voxel-based MRI analysis of plaques in AD transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:836–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boutajangout A, Li YS, Quartermain D, Sigurdsson EM. Cognitive and sensorimotor tasks for assessing functional impairments in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;849:529–40. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-551-0_35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scholtzova H, Chianchiano P, Pan J, Sun Y, Goni F, Mehta PD, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 stimulation for reduction of amyloid β and tau Alzheimer’s disease related pathology. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:101. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0101-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wisniewski T, Drummond E. Developing therapeutic vaccines against Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15(3):401415. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2016.1121815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dharmasaroja P. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of ischemic stroke. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JK, Jin HK, Bae JS. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduce brain amyloid-beta deposition and accelerate the activation of microglia in an acutely induced Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Neurosci Lett. 2009;450(2):136–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JK, Jin HK, Bae JS. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate amyloid beta-induced memory impairment and apoptosis by inhibiting neuronal cell death. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7(6):540–8. doi: 10.2174/156720510792231739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JK, Jin HK, Endo S, Schuchman EH, Carter JE, Bae JS. Intracerebral transplantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduces amyloid-beta deposition and rescues memory deficits in Alzheimer’s disease mice by modulation of immune responses. Stem Cells. 2010;28(2):329–43. doi: 10.1002/stem.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li WY, Jin RL, Hu XY. Migration of PKH26-labeled mesenchymal stem cells in rats with Alzheimer’s disease. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2012;41(6):659–64. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bae JS, Jin HK, Lee JK, Richardson JC, Carter JE. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells contribute to the reduction of amyloid-beta deposits and the improvement of synaptic transmission in a mouse model of pre-dementia Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2013;10(5):524–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JY, Kim DH, Kim JH, Lee D, Jeon HB, Kwon SJ, et al. Soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 secreted by human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cell reduces amyloid-beta plaques. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19(4):680–91. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HJ, Lee JK, Lee H, Carter JE, Chang JW, Oh W, et al. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve neuropathology and cognitive impairment in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model through modulation of neuroinflammation. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(3):588–602. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindvall O, Kokaia Z, Martinez-Serrano A. Stem cell therapy for human neurodegenerative disorders-how to make it work. Nat Med. 2004;10:S42–50. doi: 10.1038/nm1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzales-Portillo GS, Sanberg PR, Franzblau M, Gonzales-Portillo C, Diamandis T, Staples M, et al. Mannitol-enhanced delivery of stem cells and their growth factors across the blood-brain barrier. Cell Transplant. 2014;23(4–5):531–9. doi: 10.3727/096368914X678337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naaldijk Y, Jäger C, Fabian C, Leovsky C, Blüher A, Rudolph L, et al. Effect of systemic transplantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on neuropathology markers in APP/PS1 Alzheimer mice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2016. 2016 Feb 26; doi: 10.1111/nan.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]