Abstract

Cytochrome P450s and other heme-containing proteins have recently been shown to have promiscuous activity for the cyclopropanation of olefins using diazoacetate reagents. Despite the progress made thus far, engineering selective catalysts for all possible stereoisomers for the cyclopropanation reaction remains a considerable challenge. Previous investigations of a model P450 (P450BM3) revealed that mutation of a conserved active site threonine (Thr268) to alanine transformed the enzyme into a highly active and selective cyclopropanation catalyst. By incorporating this mutation into a diverse panel of P450 scaffolds, we were able to quickly identify enantioselective catalysts for all possible diastereomers in the model reaction of styrene with ethyl diazoacetate. Some alanine variants exhibited selectivities that were markedly different from the wild-type enzyme, with a few possessing moderate to high diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivities up to 97 % for synthetically challenging cis-cyclopropane diastereomers.

Keywords: biocatalysis, cyclopropanation, cytochromes, protein engineering

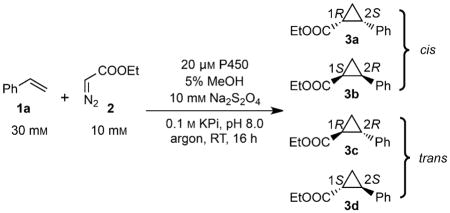

One approach to uncovering new modes of enzyme catalysis is to use man-made reagents that provide access to reactive intermediates not typically found in nature.[1] For example, intermolecular metal-catalyzed cyclopropanation is a well-characterized reaction that enables functionalization of olefins with a variety of synthetic carbene precursors. Cyclopropanes are valuable synthetic targets due to their presence in natural products and pharmaceuticals, as well as their use as synthetic intermediates that undergo stereoselective ring-opening transformations.[2] A variety of transition metal complexes, including metalloporphyrins similar to the native prosthetic group hemin, have been applied for this transformation, but the design of competent catalysts that demonstrate high diastereo- and enantioselectivity has remained challenging.[3]

Recent work by Arnold and Fasan has shown that heme-containing proteins, including members of the cytochrome P450 family of enzymes (P450s) and myoglobin, promote the promiscuous cyclopropanation of styrenes in the presence of diazoacetates.[4] In contrast to free hemin, which produces a racemic mixture of predominantly trans-cyclopropanes with low total turnover number (TTN), several native heme proteins exhibit weak to moderate stereoinduction and modest catalytic efficiency.

Engineering efforts toward cyclopropanation catalysts derived from myoglobin and the bacterial P450BM3 have resulted in increased activity and have led to the facile isolation of highly trans-selective enzymes. For example, an engineered myoglobin with two mutations from the wild-type protein showed near-perfect selectivity in the cyclopropanation of styrene, with ethyl diazoacetate (EDA) producing the 1S,2S isomer with >99 % conversion.[4a] Mutations have also been shown to affect activity. Whereas wild-type P450BM3 is a weak cyclopropanation catalyst (<5 TTN), a single active-site mutation, T268A, improved the TTN ~65 fold and produced a variant that was highly selective for the 1S,2S isomer (99:1 dr, 97 % ee; Figures 1 and 2, Table 1).[4b] Together, these studies demonstrate that the architecture of heme binding pockets can be leveraged to improve selectivity in intermolecular cyclopropanation reactions.

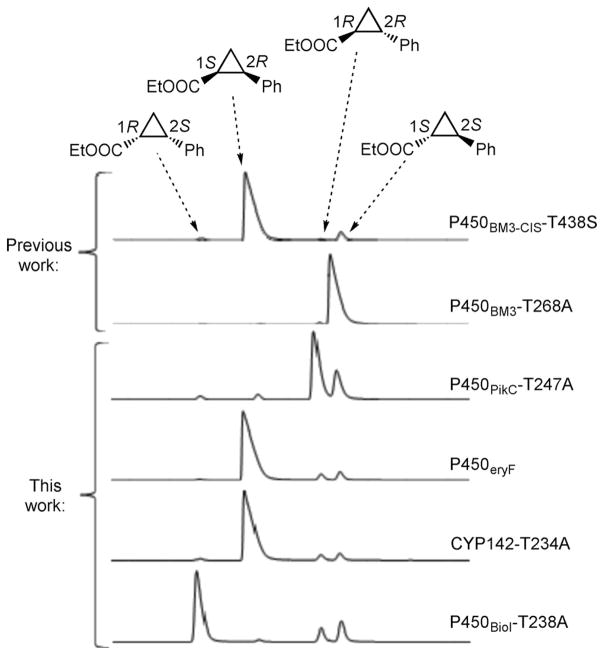

Figure 1.

Styrene cyclopropanation with ethyl diazoacetate catalyzed by P450 variants. Chiral GC traces are aligned to provide a visual representation of product distributions.

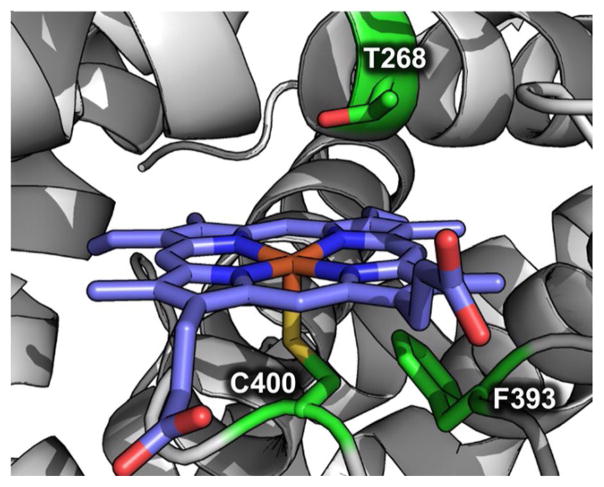

Figure 2.

Active site of substrate-free P450BM3 (PDB ID: 2IJ2). Conserved residues Thr268, Phe393, and Cys400 are shown in green, and the heme cofactor is shown in purple.

Table 1.

Activities and stereoselectivities of P450 variants for the reaction of styrene with ethyl diazoacetate.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst | Yield | TTN[a] | dr [cis:trans] | ee cis [%][b] | ee trans [%][c] |

| hemin | 16 | 79 | 13:87 | −2 | −4 |

| P450BM3 | 1 | 7 | 12:88 | 0 | −2 |

| P450BM3-T268A | 67 | 338 | 1:99 | −18 | −97 |

| P450BM3-CIS-T438S | 62 | 311 | 93:7 | −97 | −79 |

| P450BioI | 27 | 135 | 12:88 | 8 | 13 |

| P450BioI-T238A | 48 | 241 | 71:29 | 95 | −24 |

| P450cam | 41 | 207 | 88:12 | −43 | 9 |

| P450cam-T252A | 30 | 151 | 71:29 | −86 | −5 |

| P450eryF (A245) | 70 | 349 | 89:11 | −99 | −19 |

| CYP142 | 49 | 246 | 44:56 | −84 | −6 |

| CYP142-T234A | 54 | 272 | 90:10 | −97 | −14 |

| CYP164A2 | 7 | 34 | 14:85 | 5 | 2 |

| CYP164A2-T260A | 70 | 350 | 18:82 | −82 | −9 |

| CYP107N1 | 7 | 36 | 9:91 | 0 | −4 |

| CYP107N1-T251A | 48 | 238 | 9:91 | −3 | −3 |

| P450nor | 5 | 27 | 12:88 | −6 | −3 |

| P450nor-T243A | 13 | 66 | 10:90 | −3 | −2 |

| P450EpoK | 49 | 247 | 11:89 | −15 | −22 |

| P450EpoK-T258A | 44 | 219 | 18:82 | −25 | −14 |

| P450PikC | 50 | 249 | 8:92 | −2 | 3 |

| P450PikC-T247A | 46 | 231 | 7:93 | −15 | 32 |

| P450RhF | 52 | 258 | 9:91 | −3 | −2 |

| P450RhF-T275A | 34 | 171 | 12:88 | −11 | −2 |

| P450TxtE | 37 | 187 | 10:90 | 6 | −2 |

| P450TxtE-T250A | 45 | 225 | 10:90 | −2 | −2 |

| P450TylH1 | 48 | 242 | 13:87 | 16 | 8 |

| P450TylH1-T279A | 50 | 251 | 10:90 | 1 | −28 |

TTN =total turnover number.

(1R,2S)–(1S,2R).

(1R,2R)–(1S,2S).

TTNs and stereoselectivities were determined by chiral GC analysis.

Despite these efforts, engineering biocatalysts that are selective for thermodynamically unfavorable cis-diastereomers remains a challenge. Cis-selective catalysts for the cyclopropanation of styrene with EDA have been identified by screening a library of P450BM3 variants possessing diverse active sites (P450BM3-CIS-T438S, Figure 1 and Table 1);[4b,5] however, these catalysts contained a large number of mutations (>10), most of which were acquired over a decade of directed evolution. Identifying similar trajectories in other, non-cis-selective scaffolds would require considerable engineering and screening efforts. In addition, minor substitutions on styrene lead to attenuated or even reversed selectivity (vide infra).[4b,5] The difficulty in engineering cis-selective enzymes illustrates the challenge of using a single protein scaffold to alter both diastereo- and enantioselectivity.

We hypothesized that we could access stereoselective cyclopropanation catalysts by sampling a diverse library of natural P450 active sites and by introducing strategic mutations informed by previous P450BM3 engineering efforts. In P450BM3, a single mutation, T268A, significantly improves activity and selectivity, and the majority of highly active P450BM3 variants contain this mutation (Figures 1 and 2, Table 1).[4b] Because this threonine is highly conserved, we reasoned that this mutation might affect cyclopropanation activity and selectivity in other scaffolds. Here, we show that a small library composed of thirteen diverse P450s and their corresponding alanine variants allows rapid identification of selective biocatalysts for all four diastereomers of the cyclopropanation reaction.

Given the ubiquity of P450s in nature, numerous gene sequences are known that encode scaffolds that catalyze a range of oxidative and reductive transformations on a wide variety of substrates. The vast number of P450s that have been characterized or hypothesized based on genome mining makes the selection of viable sequences a non-trivial endeavor. To guide our search, we used the bioinformatics tool Deacon Active Site Profiler 2 (DASP2), which allowed us to maximize diversity by identifying scaffolds that share motifs necessary for function (e.g., the heme-ligating cysteine, Figure 2) among sequences that share little overall sequence identity (see the Supporting Information).[6] From the DASP2 search, we identified hundreds of unique P450 sequences as potential candidates for library design. The library was further narrowed down to enzymes that fit at least two of the following criteria: 1) P450s derived from bacterial origin or previously produced in Escherichia coli (to facilitate heterologous expression), 2) P450s of known structure (to aid future protein engineering), and 3) sequences that shared <20 % sequence identity with P450BM3 (to maximize active site structural variation). Our final library comprised 16 P450s, including P450BM3, with diverse activities and substrate scopes (Tables S1 and S2 and Supporting Information text). The average sequence identity across the entire library was 24 %, and the maximum identity was 46 % (P450PikC and P450eryF; Figures S1 and S2). Each enzyme contained the conserved active site threonine, with the exceptions of P450eryF and CYP122A2, which contain an alanine and a serine, respectively, at this position (Figures S1 and S3). The genes of the wild-type P450s and their corresponding alanine variants were synthesized by Gen9, Inc. Of the 31 wild-type and Thr→Ala constructs under investigation, 25 proteins were successfully purified in sufficient quantity for screening (Figure S4 and Table S1).

All of the wild-type P450s screened were active catalysts for the cyclopropanation of styrene with EDA, though to varying extents (Table 1). The threonine to alanine mutation, which was previously found to strongly activate P450BM3 variants,[4b] induced similar enhancements in three scaffolds (P450nor, CYP107N1, and CYP164A2) that showed weak native activity (<50 TTN) but experienced three- to tenfold increases in TTN upon mutation (Table 1). For example, wild-type CYP164A2 displayed negligible activity (34 TTN), whereas CYP164A2-T260A produced cyclopropanes in 70 % yield (350 TTN). Even in the absence of the mutation, nine of the wild-type P450s showed considerable activity (>200 TTN), thus indicating that the mutation is not absolutely required for high activity (Table 1). In some scaffolds, a small but significant decrease in activity was observed upon mutation, with P450cam-T252A and P450RhF-T274A showing 27 and 33 % decreases, respectively. Interestingly, wild-type P450eryF, which contains an alanine in place of the highly conserved threonine, was the most active wild-type P450 and one of the most active enzymes screened (349 TTN).

Most of the variants were trans-selective and showed hemin-like product profiles. A subset, however, possessed notable stereoselectivity (Table 1). P450PikC-T247A and P450BM3-T268A showed impressive trans-diastereoselectivity (93:7 and 99:1 dr, respectively) and moderate to excellent enantioselectivity (32 and 97 % ee) for the 1R,2R and 1S,2S isomers, respectively. The selectivity of P450BM3-T268A was consistent with previous reports.[4b] In both variants, the threonine to alanine mutation improved enantioselectivity. Interestingly, five P450s in the library were cis-selective, including a few that were highly enantioselective for the 1R,2S and 1S,2R isomers. Wild-type P450cam produced the 1S,2R enantiomer (88:12 dr) with moderate enantioselectivity (43 %), which improved to 86 % ee (71:29 dr) for the T252A variant. P450eryF, which natively contains the active site alanine, and CYP142-T234A showed strong preference for the 1S,2R isomer, catalyzing the reaction with ~90:10 dr and ≥97 % ee. Substituting the conserved threonine with alanine had a drastic effect on P450BioI, transforming the trans-selective scaffold into a highly cis-selective catalyst with unprecedented enantioselectivity among biocatalysts for the 1R,2S isomer (95 % ee, 71:29 dr). Notably, this simple, limited diversity library produced selective variants for all four possible ethyl-2-phenylcyclopropanecarboxylate diastereomers (Figure 1, Table 1).

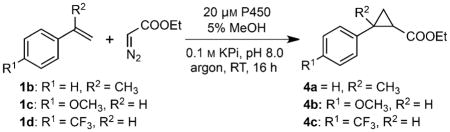

To assess how selectivity translated to other substrates, we briefly explored the substrate scope of our most selective variants compared to previously engineered trans- and cis-selective P450BM3 variants (P450BM3-T268A and P450BM3-CIS-T438S, respectively).[4b] We screened variants against styrenes with substituents at the α-vinyl position (1 b) and with electron donating or withdrawing substituents on the aromatic ring (1 c and 1 d, respectively). Tolerance to substitutions varied widely depending on the protein scaffold (Table 2). Trans-selective scaffolds P450BM3-T268A and P450PikC-T247A, identified by using styrene as a model substrate, retained moderate to high activity and trans-diastereoselectivity toward all substrates tested. Conversely, the cis-selective enzymes demonstrated more variability. For example, P450BM3-CIS-T438S retained cis-selectivity against methoxy-substituted styrene 1 c but became a trans-selective enzyme when presented with electron withdrawing substituents and increased branching on the olefin. P450BioI-T238A showed improved cis-selectivity in the presence of α-methyl styrene (1b); however, substitutions on the styrene ring led to diminished or reversed diastereoselectivity. CYP142-T234A, however, remained highly cis-selective and displayed high enantioselectivity (>90 % ee) for all substrates tested. Despite the difficulties in predicting trends, moderate to high selectivity for encumbered cis diastereomers was observed for each model substrate, using only a small P450 library.

Table 2.

Substrate scope for most selective variants from the P450 library.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | TTN[a] | dr [cis:trans] | ee cis [%][b] | ee trans [%][b] | |

| 4a | |||||

| hemin | 16 | 79 | 22:78 | 0 | −3 |

| P450BM3-T268A | 68 | 342 | 1:99 | 33 | 93 |

| P450PikC-T247A | 50 | 248 | 25:75 | 11 | −49 |

| P450BM3-CIS-T438S | 19 | 95 | 8:92 | 8 | 90 |

| P450eryF (A245) | 30 | 149 | 42:58 | −5 | −37 |

| P450BioI-T238A | 54 | 271 | 87:13 | −96 | 8 |

| CYP142-T234A | 47 | 234 | 89:11 | 94 | 0 |

| 4b | |||||

| hemin | 18 | 90 | 17:83 | 0 | n.d.[c] |

| P450BM3-T268A | 65 | 326 | 1:99 | −40 | n.d.[c] |

| P450PikC-T247A | 55 | 276 | 11:89 | −4 | n.d.[c] |

| P450BM3-CIS-T438S | 61 | 305 | 75:25 | −79 | n.d.[c] |

| P450eryF (A245) | 41 | 204 | 73:27 | −93 | n.d.[c] |

| P450BioI-T238A | 43 | 214 | 66:34 | 88 | n.d.[c] |

| CYP142-T234A | 48 | 241 | 91:9 | −96 | n.d.[c] |

| 4c | |||||

| hemin | 6 | 30 | 13:87 | −1 | n.d.[c] |

| P450BM3-T268A | 39 | 195 | 13:87 | −36 | n.d.[c] |

| P450PikC-T247A | 41 | 205 | 9:91 | 0 | n.d.[c] |

| P450BM3-CIS-T438S | 59 | 297 | 35:65 | 71 | n.d.[c] |

| P450eryF (A245) | 17 | 85 | 73:27 | −81 | n.d.[c] |

| P450BioI-T238A | 14 | 70 | 30:70 | 59 | n.d.[c] |

| CYP142-T234A | 34 | 171 | 90:10 | −96 | n.d.[c] |

TTN =total turnover number.

Stereochemistry unassigned; negative sign indicates opposite enantiomer was formed.

Not determined; baseline separation could not be achieved.

TTNs and stereoselectivities were determined by chiral GC analysis.

Interestingly, the most active and stereoselective variants presented in this study contained the mutation of the active site threonine to alanine, and the mutation tended to increase activity and/or selectivity in over half of the enzymes screened. This highly conserved residue is located in the kinked region of the i-helix (Figure S3) and has been proposed to facilitate proton delivery, activation of molecular oxygen, and the stabilization of other catalytic intermediates.[7] In cysteine-ligated P450BM3 variants, the T268A mutation is required for cyclopropanation activity. This observation initially led us to hypothesize that mutation to a smaller residue might relieve steric clash that prevents favorable binding of reactants. However, mutating the active site threonine to valine, a residue that is similar in size, also produced a highly active variant with similar selectivity to P450BM3-T268A (Figure S5). Alternatively, enzyme inactivation might result from direct carbenoid insertion into the protein scaffold (e.g., O–H insertion into the threonine side chain). However, no change in protein mass was observed after incubating the enzyme with styrene and ethyl diazoacetate. Although the mutation does not appear to cause significant changes to secondary and tertiary structure in P450BM3 (RMSD of 0.5 Å between the wild-type and T268A structures, 2IJ2 and 1YQO, respectively), backbone rearrangements in this region have been observed in other P450 crystal structures.[8] The mutation might alter hydrogen bonding networks, active site water composition, or protein dynamics that affect enzymatic cyclopropanation in a manner that has yet to be elucidated.

In summary, we have shown that natural P450 diversity provides a rich and rapid means for identifying biocatalysts with moderate to high selectivity for most cyclopropane diastereomers, including cis diastereomers that are traditionally difficult to produce. In addition, mutations identified in previous engineering experiments can guide library design, increasing the likelihood of isolating robust and stereoselective catalysts. Although the effects of the conserved threonine to alanine mutation are not universal, it provides an important target for engineering P450-based cyclopropanation catalysts. Importantly, incorporation of this mutation enabled the discovery of cis-selective catalysts that would not have been discovered by screening only the wild-type enzymes. Although there remains room for improvement, this work shows that a diversity-based strategy for incorporating key mutations can help create small, focused libraries that provide rapid access to selective starting points for further engineering and laboratory evolution.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Frances H. Arnold for providing plasmids encoding P450BM3-T268A and P450BM3-CIS-T438S. This work was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) (grant number D13AP00024) and start-up funds provided by the University of North Carolina (UNC) Chapel Hill.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201500624.

References

- 1.Arnold FH. Q Rev Biophys. 2015;48:404–410. doi: 10.1017/S003358351500013X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Alliot J, Gravel E, Pillon F, Buisson DA, Nicolas M, Doris E. Chem Commun. 2012;48:8111–8113. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33743f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen DYK, Pouwer RH, Richard JA. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:4631–4642. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35067j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Shuto S, Ono S, Hase Y, Kamiyama N, Takada H, Yamasihita K, Matsuda A. J Org Chem. 1996;61:915–923. [Google Scholar]; d) Wong HNC, Hon MY, Tse CW, Yip YC, Tanko J, Hudlicky T. Chem Rev. 1989;89:165–198. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Morandi B, Carreira EM. Science. 2012;335:1471–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.1218781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wolf JR, Hamaker CG, Djukic JP, Kodadek T, Woo LK. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:9194–9199. [Google Scholar]; c) Davies HML, Beckwith REJ. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2861–2904. doi: 10.1021/cr0200217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Doyle MP, Forbes DC. Chem Rev. 1998;98:911–936. doi: 10.1021/cr940066a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Ho CM, Zhang JL, Zhou CY, Chan OY, Yan JJ, Zhang FY, Huang JS, Che CM. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1886–1894. doi: 10.1021/ja9077254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Lai TS, Chan FY, So PK, Ma DL, Wong KY, Che CM. Dalton Trans. 2006:4845–4851. doi: 10.1039/b606757c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Mazet C, Kohler V, Pfaltz A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4888–4891. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2005;117:4966–4969. [Google Scholar]; h) Zhu S, Xu X, Perman JA, Zhang XP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12796–12799. doi: 10.1021/ja1056246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Lindsay VNG, Lin W, Charette AB. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16383–16385. doi: 10.1021/ja9044955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Bordeaux M, Tyagi V, Fasan R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:1744–1748. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2015;127:1764–1768. [Google Scholar]; b) Coelho PS, Brustad EM, Kannan A, Arnold FH. Science. 2013;339:307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.1231434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Heel T, McIntosh JA, Dodani SC, Meyerowitz JT, Arnold FH. Chem Bio Chem. 2014;15:2556–2562. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coelho PS, Wang ZJ, Ener ME, Baril SA, Kannan A, Arnold FH, Brustad EM. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:485–487. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Cammer SA, Hoffman BT, Speir JA, Canady MA, Nelson MR, Knutson S, Gallina M, Baxter SM, Fetrow JS. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:387–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fetrow JS. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2006:14:8.10:8.10.1–8.10.16. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0810s14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Huff RG, Bayram E, Tan H, Knutson ST, Knaggs MH, Richon AB, Santago P, Fetrow JS. Chem Biodiversity. 2005;2:1533–1552. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200590125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitehouse CJC, Bell SG, Wong L-L. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:1218–1260. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15192d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Girvan HM, Seward HE, Toogood HS, Cheesman MR, Leys D, Munro AW. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:564–572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607949200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) McIntosh JA, Heel T, Buller AR, Chio L, Arnold FH. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:13861–13865. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]