Abstract

This work develops serine peptide assembly (SPA), which complements and contrasts with classic native chemical ligation (NCL). Advances in reagent-less peptide bond formation have been applied to serine (and serine models) and a range of C-terminal amino acids, including bulky residues that are not amenable to NCL. The particular appeal of SPA is preparative-scale segment condensations with zero racemization risk and favourable process mass intensity (PMI). Mechanistic studies support a previously proposed reaction pathway via an initial trans-esterification step. An understanding of the factors favouring this pathway relies on hard-soft acid-base theory, where mildly activated esters with the largest carbonyl positive charge are most reactive with hydroxy amines. Novel C-terminal activators have been discovered that enhance reactivity and give harmless by-products.

Keywords: amides, amino acids, acylation, nucleophilic substitution, transesterification

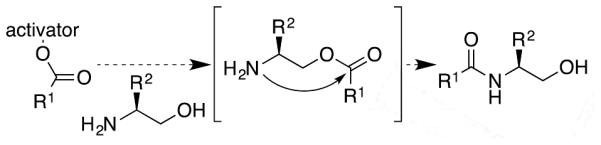

We recently introduced a method for reagent-less amide bond formation with a focused set of amines, those bearing nearby hydroxy groups.[1] Their carboxyl reaction partners were esters mildly activated for acyl transfer by strain or inductive effects or both. We suggested the pathway for these reactions involves initial trans-esterification of the alcohol and ensuing rearrangement to give the more stable hydroxy amide. Envisioning application of this technology to preparative peptide segment condensations at N-terminal serine residues, we aimed here to expand the scope to diverse activated acyl derivatives, including native amino acids with variant mildly activated esters. This work provides further support for the trans-esterification/rearrangement pathway that mimics native chemical ligation (NCL) and has uncovered readily introduced, superior C-terminal activating groups.

Our earlier work was limited to N-Boc-valine. The valine carboxylate was activated as a cyanomethyl ester or oxazolidinone (1). Nonetheless, successful amide formation with this amino acid derivative (with its bulky α-substituent) far surpasses the capabilities of the sulfur relative of SPA, NCL.[2] There, valine is tolerated at the C-terminus only when using a selenoester with selenocysteine.[3] Assemblies were performed in relatively non-polar media at ambient temperature for extended periods, or more rapidly via microwave heating.

To study a reaction partner that better represents the C-terminus of a peptide segment, we replaced carbamate N-protection from the earlier study with an N-acetyl group. Particularly, N-acyl amino acids (like peptide C-termini) are vulnerable to racemization when the carboxylate is activated with conventional coupling agents, owing to competing oxazolone formation, which labilizes the α-hydrogen of the C-terminal residue. In examining the relative reactivity of different native amino acids, L-alaninol was used as a simple serine surrogate. Each of the known acetyl amino acids in Table 1 was converted to its cyanomethyl (CM) ester 3 in 80-95% yield using the conditions earlier reported, 1 eq Cs2CO3, 1.5 eq BrCH2CN, ambient, 1.5-8 h. These esters were allowed to react with a 50% excess of alaninol, either at ambient or with microwave heating at 100 °C, in 1M solutions. Ethyl acetate proved a useful solvent for these reactions, dissolving polar reactants that are insoluble in the hydrocarbons that were earlier preferred, but still providing a relatively non-polar medium that gives higher conversions. Results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Peptide bond formation with W-acetylamino cyanomethyl esters

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Entry | Ac-AA | Time (h)[[a]] | Yield (%) | Time (min)[[b]] |

Yield (%) |

|

| |||||

| a | Val | 72 | 78 | 90 | 78 |

|

| |||||

| b | Leu | 72 | 38 | 90 | 53 |

|

| |||||

| c | Phe | 48 | 76 | 90 | 76 |

|

| |||||

| d | Met | 48 | 90 | 90 | 91 |

|

| |||||

| e | Pro | 72 | 64 | 90 | 54 |

|

| |||||

| f | Gly | 72 | 72 | 90 | 73 |

|

| |||||

| g | (Trt)Asn | 24 | 79 | ND[[c]] | ND |

|

| |||||

| h | (Bn)Cys | 48 | 78 | ND | ND |

|

| |||||

ambient;

microwsave heating;

ND - not determined

The Table shows that significant variation in the C-terminal amino acid is very well-tolerated. Leucine is a slower reactant, which can be understood based on syn-pentane interactions or other remote steric effects.[4] Successful reaction with proline is notable, as Pro (like Val) is not useful in NCL.[5] Though some advancements have been made in this area,[6] C-terminal bulk is still a significant problem for NCL. No racemization (<0.1%) was observed in any of these reactions, as established by detailed spectroscopic examination of the products in comparison with the peptide diastereomer generated with D-alaninol.

We also aimed to provide greater support for the mechanism postulated earlier; that is, an initial trans-esterification that is enhanced by internal H-bonding between the basic amine and the hydroxyl group, followed by a rearrangement (via trans-acylation) to produce the hydroxyamide. Structural variations were made to the amino-alcohol to examine this issue. As Table 1 shows, when Ac-Val-OCM reacts with alaninol under ambient conditions, formation of 4a is complete in 72 h. When N,N-dimethylalaninol is substituted, the trans-esterification product 5 is formed in 89% yield, also in 72 h. When alaninol N-formamide is used, there is no reaction. When alaninol tert-butyldimethylsilyl ether is used, there is no reaction. We showed earlier that alaninol tert-butyldimethylsilyl ether does not react with a γ−lactone, demonstrating the essential nature of the alcohol to these amide-forming reactions. The current results show that trans-esterification is kinetically competent as the initial step in the overall process, that direct acylation is not a favourable reaction pathway, and that trans-esterification requires a nearby basic nitrogen. All of these data support the mechanism discussed above, as explicitly detailed in Scheme 3.

Scheme 3.

The trans-esterification/rearrangement mechanism

The N-acetyl oxazolidinones 6 of several native amino acids were also investigated. These are prepared from the N-acetyl amino acids in 55-84% yield by treatment with p-TSA and paraformaldehyde in toluene for 3-12 h. As Table 2 shows, the trends observed in the CM ester study hold here, with the Leu derivative again being lower-yielding.

Table 2.

Peptide bond formation with N-acetyl oxazolidinones

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Entry | Ac-AA | Time (h)[[a]] | Yield (%) | Time (min)[[b]] |

Yield (%) |

|

| |||||

| a | Val | 72 | 81 | 90 | 78 |

|

| |||||

| b | Leu | 72 | 41 1 | 90 | 58 |

|

| |||||

| c | Phe | 48 | 78 | 90 | 74 |

|

| |||||

| d | Met | 36 | 82 | 90 | 76 |

|

| |||||

ambient.

microwsave heating

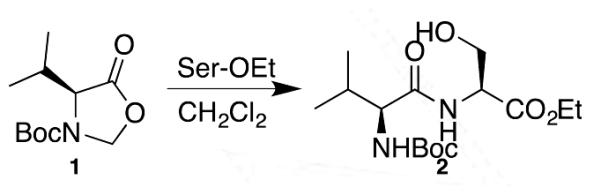

When extending these reactions of 3a or 6a to SPA with ethyl serinate, a reactant more representative of a peptide N-terminus, yields were only moderate. This stimulated the search for superior C-terminal mildly activated esters that could be readily generated from peptides. Boc-Val was used as a test amino acid as it maintains the steric demand uniquely tolerated in hydroxy amine amidation while enabling the rapid synthesis of a wide range of esters using multiple conventional methods.

This study was performed by treating valine esters 7 with alaninol under our standard ambient reaction conditions and observing the time for complete consumption of starting material, forming 8. The results in Table 3 show interesting features. Despite past precedent using CM esters in trans-esterification reactions,[7] they are among the slowest of the reactive esters investigated. A significant rate gain is seen with fluorinated esters, the best being the vinyl esters. The fastest, (methyl trifluorocrotonate)yl (entry m), is prepared by conjugate addition[8] of the carboxylate to ethyl trifluorobutynoate. Hexafluoroisopropyl (HIP) and trifluoroethyl (TFE) esters also have good reactivity. Some other Boc-Val esters (structures in the ESI) show essentially no reaction, despite a reasonable expectation of good reactivity based on their group electronegativities (vide infra).

Table 3.

Boc-Val-ester reactivity under ambient conditions

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Entry | R | Time (h) |

|

| ||

| a | CH2SCH3 | 84 |

|

| ||

| b | CH2CCl3 | 80 |

|

| ||

| c | CH2CH2Cl | 76 |

|

| ||

| d | CH2CN | 70 |

|

| ||

| e | CH2CHCl2 | 54 |

|

| ||

| f | CH2SOCH3 | 50 |

|

| ||

| g | CH2SO2CH3 | 48 |

|

| ||

| h | CH2CF3 | 32 |

|

| ||

| i | CH2CF2CF3 | 28 |

|

| ||

| j | CH(CF3)2 | 18 |

|

| ||

| k | C=CH2(C(CF3)2CF2CF3) | 18 |

|

| ||

| l | (MeO2C)C=CH(CO2Me) | 15 |

|

| ||

| m | (CF3)C=CH(CO2Me) | 8 |

|

| ||

Preparative yields for SPA with ethyl serinate for the six most reactive esters 7 were determined under the standard reaction conditions. Additional products that diminished the isolated yields of Boc-Val-Ser-OEt (2) were observed with the three vinyl esters, but the HIP and TFE esters gave >92% yields of the product in 20-32 h under ambient conditions. Experiments to establish the reaction pathway for amide formation were performed with 7j to parallel those with 3a (Scheme 2), with the same outcomes: the trans-esterification product forms from N,N-dimethylalaninol in 94% yield in the same reaction time, so that step is kinetically competent, and no other alaninol analogs react.

Scheme 2.

Results supporting the trans-esterification/rearrangement pathway

Identification of these superior esters prompted development of methods for mild ester formation from free C-termini using N-Ac-Val as a model. In Sn2 reactions with the carboxylate as the nucleophile, commercially available trifluoroethyl triflate proved about as reactive in forming TFE esters as the bromoacetonitrile used to make CM esters, providing the ester in essentially quantitative crude yield in a few hours. However, the TFE ester is more desirable because it is more reactive and its by-product is volatile and non-toxic. Like CM esters, mildly activated TFE esters are formed without generating a reactive acylating agent from the carboxyl group, eliminating any concerns about racemization via oxazolone formation. These reactions have been performed on scales up to 1 g of TFE ester 9. It is stable upon storage and has proved resistant to racemization even with microwave heating in ethyl acetate under reaction conditions in the absence of a hydroxyamine. We generally observe that these mildly activated esters can be used in 20-50% excess and that the unreacted starting material can be recovered following reaction and reused.

We applied serine peptide assembly to two simple examples. On treatment of 9 with seryl-phenylalanine ester, tripeptide 10 forms in 76% yield in 36 h (RT). Changing the CM ester to the TFE ester mitigated the earlier difficulty with leucine, as treatment of 11 with seryl-phenylalanine ester forms tripeptide 12 in 66% yield (48 h, RT).

As many chemists would judge nitrogen intrinsically more nucleophilic than oxygen, the mechanistic pathway inferred for SPA is counterintuitive. Likewise, it could be said that sulfur is more nucleophilic than either, hence its utility in NCL. However, it is known that oxy anions are more nucleophilic than amide anions, as shown by Brønsted linear free energy relationships in substitution reactions (on benzyl chloride).[9] The accessibility of the oxy anion is also generally better owing to intrinsically lower pKAs for alcohols than for amines, and specifically in these reactants based on the internal basic amine.

In considering these results, we aimed to develop structure-reactivity correlations that would enable understanding and prediction of ester reactivity in SPA (tables in the ESI). Group electronegativity data is available for some of the ester groups used, but it shows poor agreement with reactivity. For example, the ethynyl and cyano groups have the same group electronegativity (3.3),[10] but propargyl esters are unreactive whereas cyanomethyl esters react fairly well. Other correlations were based on electronic structure calculations using the PM3 semi-empirical method. The LUMO energies and carbonyl electrostatic charges were examined for acetyl derivatives of ester groups from Table 3, as well as other commonly used active esters. The best predictor of the observed reactivity (with alaninol) was carbonyl carbon electrostatic charge. We interpret this preference as the hard nucleophile alkoxide transesterifying faster with harder carbonyls.

Of the metrics that have been proposed to evaluate the sustainability of chemical processes, a prominent measure is process mass intensity (PMI).[11] This is the ratio of the mass of all materials entering a reaction (excluding aqueous solvents) to the mass of final product, with the best possible PMI being 1. For the preparation of tripeptides 10 and 12 using SPA, the 2-step PMI is ~5. This is a relatively low value and contrasts with higher PMI using conventional peptide couplings that include condensing agents and additives to suppress racemization that are unnecessary in SPA.

This work complements the substantial achievements in ligations at Ser and Thr residues with unprotected polypeptides in dilute aqueous media.[12]

Experimental Section

Ac-Val-OTFE (9). Cesium carbonate (1.0 mmol, 325.3 mg) was added to a solution of N-Ac-Val (1.0 mmol, 217.3 mg) in 10 mL of acetonitrile. This solution was stirred at room temperature for 15 min and then 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (1.5 mmol, 348.2 mg) was added in one portion. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h and filtered through Celite. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo and purified using silica gel flash chromatography using ethyl acetate as eluent to yield 228 mg (95% yield) of the title compound as a colorless oil. Ac-Val-Ser-Phe-OMe (10). Ac-Val-OTFE (0.15 mmol, 36.6 mg) was added to a solution of Ser-Phe-OMe (0.13 mmol, 33.6 mg) in 0.13 mL of ethyl acetate. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 36 h and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by silica gel chromatography using 10% methanol in dichloromethane as eluent to yield 48.7 mg (76% yield) of the title compound as a white solid. mp 202 °C dec.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Initial peptide assembly with serine

Scheme 4.

Preparative yields of 2 were determined with the six most reactive esters

Scheme 5.

Model tripeptide syntheses using SPA of TFE esters

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by grants from NSF (CHE 1362737) and NIH (AI106597). We are grateful to Kian Sedighi and Jody Gotoc for technical assistance.

References

- [1].Pirrung MC, Zhang F, Ambadi S, Ibarra-Rivera TR. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012:4283. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hackeng TM, Griffin JH, Dawson PE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:10068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mitchell NJ, Malins LR, Liu X, Thompson RE, Chan B, Radom L, Payne RJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;131:14011–4. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Shtyrlin YG, Fedorenko VY, Klimovitskii EN. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2001;71:819–820. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pollock SB, Kent SB. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:2342. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04120c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hinderaker MP, Raines RT. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1188. doi: 10.1110/ps.0241903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Choudhary A, Raines RT. Protein Sci. 2011;20:1077. doi: 10.1002/pro.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhang Q, Yu H-Z, Shi J. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 2013;29:2321–2331. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Raibaut L, Seeberger P, Melnyk O. Org. Lett. 2013;15:5516–5519. doi: 10.1021/ol402678a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Duca M, Chen S, Hecht SM. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:3292–3299. doi: 10.1039/b806790b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Goto Y, Suga H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5040–5041. doi: 10.1021/ja900597d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fan M-J, Li G-Q, Liang Y-M. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:6782–6791. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bordwell FG, Hughes DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:3234. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wells PR. Prog. Phys. Org. Chem. 1968;6:111. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jiménez-González C, Constable DJC, Ponder CS. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:1485–1498. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15215g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Liu H, Li X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:3768–3773. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00392f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pusterla I, Bode JW. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:668–72. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Malins LR, .Mitchell NJ, McGowan S, Payne RJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:12716–21. doi: 10.1002/anie.201504639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.