Abstract

Purpose

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are effective in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), but often are of transient benefit as resistance commonly develops. Immunotherapy, particularly blockade of the inhibitory receptor programmed death 1 (PD-1) or the ligand programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), has shown effectiveness in a variety of cancers. The functional effects of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade are unknown in GIST.

Experimental Design

We analyzed tumor and matched blood samples from 85 patients with GIST and determined the expression of immune checkpoint molecules using flow cytometry. We investigated the combination of imatinib with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in KitV558Δ/+ mice that develop GIST.

Results

The inhibitory receptors PD-1, lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3), and T cell immunoglobulin mucin-3 (TIM-3) were upregulated on tumor-infiltrating T cells compared to T cells from matched blood. PD-1 expression on T cells was highest in imatinib-treated human GISTs. Meanwhile, intratumoral PD-L1 expression was variable. In human GIST cell lines, treatment with imatinib abrogated the IFN-γ–induced upregulation of PD-L1 via STAT1 inhibition. In KitV558Δ/+ mice imatinib downregulated IFN-γ–related genes and reduced PD-L1 expression on tumor cells. PD-1 and PD-L1 blockade in vivo each had no efficacy alone, but enhanced the antitumor effects of imatinib by increasing T cell effector function in the presence of KIT and IDO inhibition.

Conclusions

PD-1/PD-L1 blockade is a promising strategy to improve the effects of targeted therapy in GIST. Collectively, our results provide the rationale to combine these agents in human GIST.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, targeted therapy, PD-1, PD-L1, immunotherapy

INTRODUCTION

The advent of targeted molecular therapy has revolutionized the treatment of many cancers, including gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). The majority of GISTs contain an activating mutation in either the KIT or PDGFRA oncogene (1, 2). Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that specifically targets KIT and PDGFRA (3). The tumor response to imatinib in GIST is impressive, but most often transient. Resistance commonly develops within 2 years, often due to a secondary KIT mutation (4, 5). Imatinib acts primarily via direct effects on tumor cells. However, we previously showed that imatinib also inhibits tumor cell production of the immunosuppressive enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) (6).

Many tumors express ligands that engage inhibitory receptors on T cells and decrease T cell activation and function within the tumor microenvironment. There is growing evidence that tumor cells commonly exploit the programmed death 1 (PD-1, PDCD1) and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1, PDCD1LG1) axis to evade the immune system (7). PD-1 is an inhibitory receptor that is upregulated after T cell activation and remains elevated with antigen persistence and therefore is often increased on tumor-infiltrating T cells (8–10). The ligands for PD-1 are PD-L1 (B7-H1, CD274) and PD-L2 (B7-DC, CD273, PDCD1LG2). PD-L1 is expressed widely on immune cells and can be upregulated by pro-inflammatory stimuli, such as interferons, but is also expressed by tumor cells in a variety of cancers (11). PD-L1 expression on tumors can lead to impaired T cell proliferation and effector function, leading to apoptosis of tumor-specific T cells (12). PD-L2 expression is restricted mostly to hematopoietic cells. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade has demonstrated encouraging antitumor effects in several solid tumors, including kidney, bladder, and lung cancer, as well as melanoma (13–19).

Despite the efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibition, nearly all patients with metastatic GIST develop tumor progression and eventually succumb to their disease. There has not been any improvement in the first-line therapy for GIST since imatinib was approved in 2002. In this study, we analyzed freshly isolated T cells from the tumor and peripheral blood of patients with GIST for the expression of inhibitory receptors. We determined the effects of imatinib on IFN-γ–related genes and the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in GIST. Furthermore, in a genetically engineered mouse model of GIST, we tested the combination of imatinib with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient samples

Tumor specimens and matched peripheral blood were obtained from 85 GIST patients who underwent surgery at our institution and were consented to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board. Blood was drawn before surgical incision and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density centrifugation over Ficoll-Plaque PLUS (GE Healthcare). Tumor tissue was subjected to mechanical dissociation to obtain single-cell suspensions, as described previously (6). After procurement, all specimens were processed and cells were immediately analyzed with flow cytometry. Tumor (KIT+) and stromal cells (KIT−) were isolated using human CD117 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of isolated cells was greater than 90% by flow cytometry.

Cell lines and treatments

The human GIST cell lines GIST-T1 (KIT exon 11 mutant; (20)), HG129 (also KIT exon 11 mutant; (21)), and GIST882 (KIT exon 13 mutant; provided by Jonathan Fletcher) were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10 mM Hepes. Cells were incubated with recombinant human IFN-γ (100 ng/ml; R&D Systems), imatinib (100 nM; Novartis), or the pan-Janus-activated kinase (JAK) inhibitor tetracyclic pyridine 6 (P6; 1 μM; provided by Jacqueline Bromberg (22)).

Mice and treatments

KitV558Δ /+ mice (23) that were 6–12 weeks old were maintained in a specific pathogen-free animal facility, age- and sex-matched for experiments, and used in accordance with an institutional approved protocol. Tumors were minced, incubated in 5 mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich) plus 0.5 mg/ml DNAse I (Roche Diagnostics) in HBSS for 30 min at 37°C, then quenched with FBS, and washed through 100 and 40 μm nylon cell strainers (Falcon; BD Biosciences) in PBS with 1% FBS. Tumor-draining lymph nodes and spleens were mechanically dissociated as previously described (6). Cells were immediately analyzed with flow cytometry. Imatinib was administered at 90 mg/kg/day in the drinking water. 1-methyl-D-tryptophan (1-MT; Sigma Aldrich) was prepared and administered twice daily by oral gavage at 400 mg/kg/day as before (6). Anti-PD-1 (RMP1-14; BioXcell) or anti-PD-L1 (10F.9G2; BioXcell) blocking antibodies or isotypes (rat IgG2a or rat IgG2b) were administered i.p. at a dose of 250 μg and 200 μg per mouse, respectively, at the indicated time points. Murine T cells were purified from mesenteric lymph nodes from C57BL/6J mice (B6, Jackson Laboratory) and tumors from KitV558Δ /+ mice using CD3-biotin and anti-biotin MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Positive selection was performed using two sequential MACS columns. CD3+ T cells were then cultured in anti-CD3-coated 96-well plates (BD Biosciences) with 10 μg/ml of either anti-PD-1 antibody or isotype, and supernatant was harvested at 48 h.

Flow cytometry and cytokine detection

Human-specific antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (CD45, 2D1; CD3, SK7; CD4, RPA-T4; PD-1, MIH4), eBioscience (CD8, RPA-T8), BioLegend (PD-L1, 29E.2A3), R&D Systems (TIM-3, 344823), and Enzo Life Sciences (LAG-3, 17B4). Mouse-specific antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (CD3, 125-2C11; CD4, GK1.5; CD44, IM7; CD62L, MEL-14; PD-L1, MIH5; CD69, H1.2F3; IFN-γ, XMG1.2; TNF, MP6-XT22), eBioscience (CD8, 53-6.7; PD-1, J43; PD-L2, 122; Foxp3, FJK-16s; Ki67, SolA15; Granzyme B, NGZB), and BioLegend (CD45, 30-F11; PD-L1, 10F.9G2; CD25, PC61). Appropriate isotype controls were used where applicable. A viability dye was typically used to exclude dead cells. Intracellular staining was performed using the eBioscience Fixation and Permeabilization Buffer Kit. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (750 ng/ml) for 4 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 in the presence of 1 μg/ml brefeldin A (BD Biosciences). Surface staining was performed and cells were fixed and permeabilized with the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit and stained for IFN-γ and TNF- α. Supernatant cytokines were measured by cytometric bead array according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Mouse Inflammation Kit; BD Biosciences). Data were acquired using a BD FACSAria or Fortessa LSR flow cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimens were sectioned at 5 μm thickness and mounted on glass slides. The PD-L1 (clone 5H1) antibody was obtained from Lieping Chen (12). In brief, antigen retrieval was achieved with citrate buffer. Anti-PD-L1/B7-H1 murine IgG (1:1000) was applied on tissue sections overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBS (0.05 M Tris base, 0.9% NaCl, pH 8.4), tissue sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (1:100; BA-2001, Vector Laboratories) followed by incubation with Elite ABC kit for 30 min at room temperature. Antibody binding was detected with the TSA Biotin System (NEL700A001KT, PerkinElmer) and DAB (DAKO, K3468). Murine PD-L1 staining was performed using the polyclonal antibody against mouse B7-H1/PD-L1 antibody (1:100, R&D Systems). Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and KIT immunostaining (1:200, D13A2; Cell Signaling Technology) were performed as described (24). Slides were analyzed and imaged on the Axio Imager 2 wide-field microscope (Zeiss).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from each human GIST specimen, cell line, or murine GIST specimen, reverse-transcribed, and amplified with PCR TaqMan probes for human PDCD1LG1 (i.e. PD-L1, Hs01125301_m1), IFNGR1 (Hs00988303_m1), IRF1 (Hs00971960_m1), GAPDH (Hs02758991_g1), murine Pdl1 (Mm00452054_m1), Ido1 (Mm00492590_m1), and Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1, all Applied Biosystems). Quantitative PCR was performed using a ViiATM7 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Relative expression was calculated by the 2− Δ ΔCt method according to the manufacturer’s protocol and expressed as the fold increase over the indicated control.

STAT1 knockdown

For transient STAT1 knockdown, GIST-T1 cells were transfected with 30 nmol/L of ON-TARGET plus SMARTpool siRNA specific for human STAT1 (L-003543-00) or a non-target control siRNA (D-001810-10-05; Thermo Scientific) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) for 48 h. GIST-T1 cells were treated with PBS or IFN-γ (100 ng/ml) for 6 h.

Western blot and cytokine array

Western blot of whole protein lysates from frozen tumor tissues or cells was performed as previously described (6). Antibodies for PD-L1 (E1L3N), phosphorylated SRC (Tyr416), phosphorylated STAT1 (Tyr701), phosphorylated STAT3 (Ser727 or Tyr705), total and phosphorylated KIT (Tyr719), phosphorylated ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), phosphorylated SMAD2 (Ser465/467), TGFβ and GAPDH were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-IDO antibody (clone 10.1) was purchased from EMD Millipore. Whole protein from frozen tumor tissues was lysed and total protein was tested for cytokine/chemokine expression using a Proteome Profiler Array (R&D Systems). Densitometry was conducted on blots using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM or median. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA comparisons were performed as applicable using Graph Pad Prism 6.0 (Graph Pad Software). A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

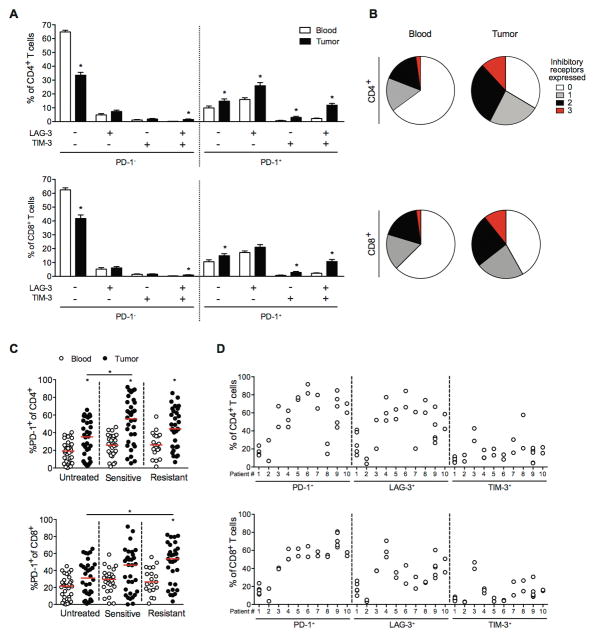

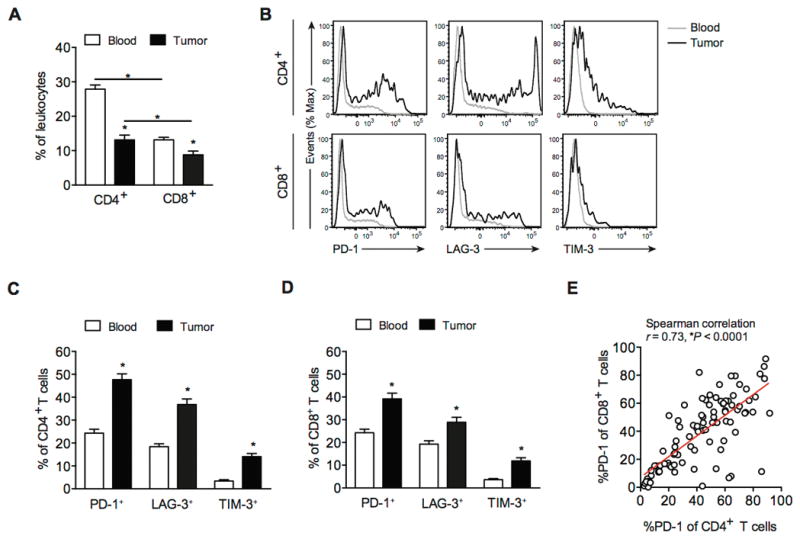

T cells infiltrating human GIST express high levels of inhibitory receptors compared with blood

The inhibitory receptors PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3 (HAVCR2) are typically expressed on antigen-specific and dysfunctional T cells within tumors and during chronic viral infection (10, 25). To identify the inhibitory receptors that are relevant in GIST, we performed flow cytometry on T cells from 106 tumor specimens and matched blood, freshly obtained from 85 GIST patients undergoing surgery (Supplementary Table S1). The percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells among leukocytes were lower in tumors than in matched blood. CD8+ T cells were less frequent than CD4+ T cells in both compartments (Fig. 1A). Intratumoral T cells displayed greater cell surface expression of PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3 compared with T cells from matched blood (Fig. 1B–D). PD-1 was expressed at the highest levels on both intratumoral CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (48% and 39%, respectively). Moreover, the percentage of PD-1 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells correlated within the same tumor specimen (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1. T cells infiltrating human GIST express high levels of inhibitory receptors compared with blood.

(A) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as a percentage of leukocytes (CD45+ cells) in matched blood and tumor specimens (n = 106) from 85 human GIST patients. (B) Histograms of PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in blood (gray), and tumor (black) from a representative sample. PD-1+, LAG-3+, and TIM-3+ cells as percentage of CD4+ (C) and CD8+ T cells (D) from matched peripheral blood and tumor samples. (E) Linear regression analysis between PD-1 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in 106 human GIST specimens. Data represent mean ± SEM *P < 0.05.

Patterns of PD-1 expression in T cells in human GIST

The expression of inhibitory receptors on tumor-infiltrating T cells suggested that T cell immune evasion occurs in human GIST. PD-1+ T cells tended to also express LAG-3 and less frequently TIM-3 (Fig. 2A). In contrast, PD-1− T cells had little expression of LAG-3 or TIM-3. The majority of T cells from matched blood did not express any inhibitory receptors (Fig. 2B). Previously, we showed that tumors sensitive to tyrosine kinase inhibition (based on serial radiologic assessment prior to surgery) contained more CD3+ and CD8+ T cells, but a lower percentage of CD4+ T cells and Tregs compared with untreated and resistant tumors (6). Here, we found that compared with untreated tumors, there was higher PD-1 expression on CD4+ T cells in sensitive tumors and CD8+ T cells in tumors with acquired resistance to imatinib (i.e., increasing tumor size or vascularity after a period of stable or shrinking disease by serial radiologic assessment) (Fig. 2C). There was no association between PD-1 expression and type of oncogene mutation (KIT, PDGFRA, or wild type), tumor location, size, or mitotic rate (data not shown). In 10 patients who had multiple tumors removed during surgery, we found a similar expression pattern of inhibitory receptors within individuals, despite differences in tumor location, size, and mitotic rate (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Patterns of PD-1 expression in T cells in human GIST.

(A) Expression of individual or the combination of inhibitory receptors (PD-1, LAG-3, TIM-3) on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in 63 human GIST specimens by Boolean gate analysis. Data represent mean ± SEM *P < 0.05. (B) Total number of inhibitory receptors expressed by CD4+ (top) and CD8+ T cells (bottom) from the blood (left) and tumor (right). (C) Percentage of PD-1+ cells among CD4+ (top) and CD8+ T cells (bottom) in blood and tumor from untreated (n = 36), imatinib-sensitive (n = 38), and imatinib-resistant (n = 32) GIST specimens. Each dot represents a separate specimen. Median values are marked by a horizontal red line. *P < 0.05. (D) Expression of inhibitory receptors on tumor-infiltrating T cells from GIST patients with multiple metastases (n = 10). Each dot represents a separate tumor specimen.

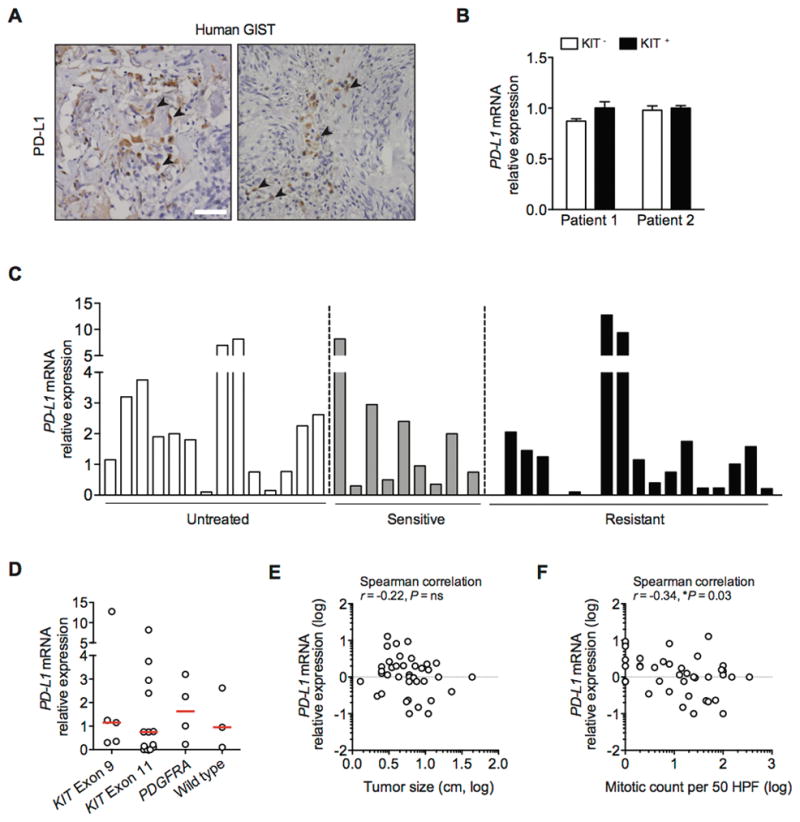

PD-L1 is expressed in a subset of human GISTs

To assess the expression of PD-L1 in human GIST, we evaluated human GIST specimens by immunohistochemistry. PD-L1 expression was low in most cases and tended to be focal (Fig. 3A). PD-L1 was present on tumor cells, but also on some intratumoral leukocytes. To ascertain the relative location of PD-L1 within the tumor, we measured PD-L1 mRNA levels in freshly isolated tumor (CD45−KIT+) and stroma (CD45−KIT−) cells from 2 resistant human GISTs. PD-L1 mRNA was equally distributed between these 2 compartments (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, we performed real-time PCR on 41 bulk human GIST samples. The PD-L1 mRNA level was variable, but did not appear to correlate with treatment response to tyrosine kinase inhibition (Fig. 3C), mutation (Fig. 3D), or tumor size (Fig. 3E). There was a weak inverse relationship between mitotic rate and PD-L1 expression (Fig. 3F). Overall, intratumoral PD-L1 expression was variable and heterogeneous.

Figure 3. PD-L1 is expressed in a subset of human GISTs.

(A) Representative immunohistochemistry with anti-PD-L1 (clone 5H1) shows membranous and cytoplasmic expression in human GIST (indicated by black arrow; scale bar 50 μm). (B) Freshly isolated KIT- (stroma) and KIT+ (tumor) cells from 2 human GISTs were analyzed for PD-L1 mRNA by real-time PCR. Bars represent mean ± SEM. (C) RNA was isolated from fresh frozen untreated (n = 14), imatinib-sensitive (n = 9), and imatinib-resistant (n = 18) human GISTs and analyzed for PD-L1 mRNA using real-time PCR. Bars represent means. (D) PD-L1 mRNA relative expression in 25 GIST samples with confirmed mutation. Median values are marked by a horizontal red line. (E) Scatter plots to analyze the correlation of PD-L1 mRNA with tumor size and (F) mitotic count. Values are log-transformed.

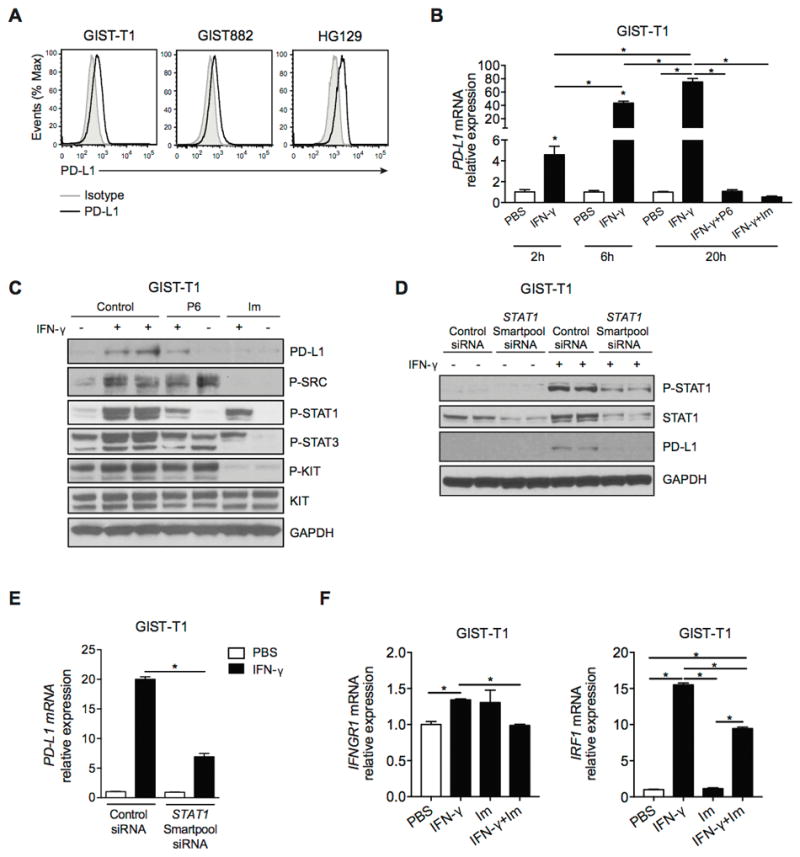

Imatinib abrogates IFN-γ–induced upregulation of PD-L1 on human GIST cell lines

Next, we found that PD-L1 expression was low on 3 imatinib-sensitive human GIST cell lines (Fig. 4A). Because IFN-γ is known to induce PD-L1 expression (12), we tested its effect on GIST cell lines. IFN-γ upregulated PD-L1 mRNA in GIST-T1 cells over time as measured by real-time PCR (Fig. 4B). Similar results were observed in GIST882 and HG129 cells (data not shown). IFN-γ–induced upregulation of PD-L1 transcripts was abolished with either the JAK inhibitor pyridine 6 or the KIT inhibitor imatinib. IFN-γ treatment also induced PD-L1 protein expression, but imatinib abrogated the effect as measured by flow cytometry (data not shown) and western blot (Fig. 4C). The mechanism appeared to be partly through the inhibition of STAT-1 activation, since JAK inhibition by pyridine 6 also reduced PD-L1 upregulation and, like imatinib, was associated with decreased phosphorylated STAT1 (Fig. 4C) and STAT1 mRNA levels (data not shown). Furthermore, STAT1 knockdown by siRNA in GIST-T1 cells blocked IFN-γ–induced upregulation of PD-L1 protein and mRNA (Fig. 4D, 4E). STAT1 knockdown was confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 4D). We next measured the mRNA levels of IFN-γ receptor (IFNGR1) and its major downstream signaling component IFN response factor 1 (IRF1). Notably, imatinib reduced the IFN-γ–mediated increase in IFNGR1 and IRF1 mRNA (Fig. 4F). Collectively, IFN-γ played a significant role in the regulation of PD-L1 expression in human GIST cells, but its effect was inhibited by imatinib.

Figure 4. Imatinib abrogates IFN-γ–induced upregulation of PD-L1 on human GIST cell lines.

(A) PD-L1 expression in human GIST cell lines as determined by flow cytometry. Gray histograms represent isotype controls. (B) GIST-T1 cells were treated with either PBS, IFN-γ (100 ng/ml), IFN-γ plus the JAK inhibitor tetracyclic pyridine 6 (P6; 1 μM), or IFN-γ plus imatinib (Im; 100 nM). PD-L1 mRNA relative expression was determined at the indicated time points by real-time PCR. (C) Western blot of GIST-T1 treated as described above for 20 h. (D) GIST-T1 cells were transfected with non-target control siRNA or ON-TARGET plus SMARTpool siRNA (STAT1 siRNA) and then treated with PBS or IFN-γ (100 ng/ml) for 6 h. Western blot analysis demonstrating efficiency of STAT1 knockdown and PD-L1 expression. (E) PD-L1 expression in GIST-T1 cells was measured by PCR. (F) GIST-T1 cells were analyzed for IFNGR1 and IRF1 by real-time PCR after 6 h of the indicated treatment. Data are normalized to control. Data represent mean ± SEM *P < 0.05.

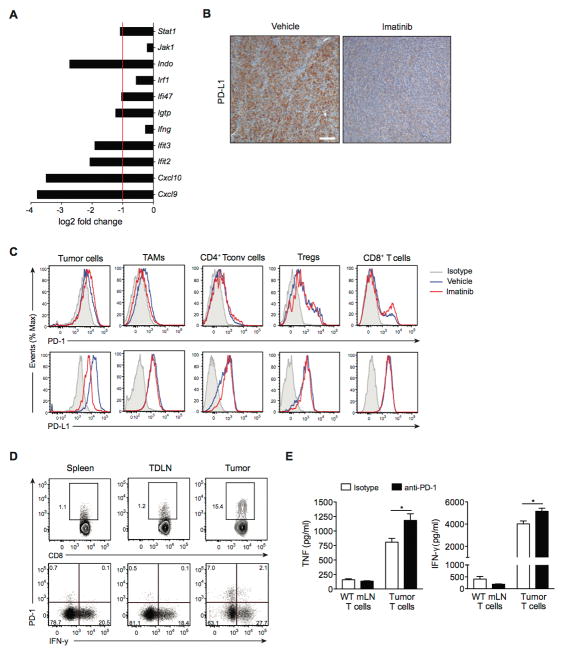

Imatinib modulates IFN-γ–related genes and PD-L1 expression in GIST

To determine whether imatinib also alters tumor IFN-γ signaling in KitV558Δ/+ mice, we assessed IFN-γ–related genes in our previously published mRNA microarray data (6). After 1 week of imatinib therapy, the expression of multiple IFN-γ–related genes was reduced in bulk tumor (Fig. 5A). Pdl1 was not present on the array. Notably, PD-L1 expression was markedly reduced after 4 weeks of imatinib by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5B). To further investigate the extent to which imatinib treatment modulates PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in GIST, we performed flow cytometry on intratumoral T cells, and tumor cells (Fig. 5C). PD-L1 was present on tumor cells, and decreased with 1 week of imatinib treatment. PD-L2 expression was minimal (data not shown). T cell subsets within the tumor expressed both PD-1 and PD-L1 at baseline, but imatinib had little to no effect on expression levels. CD8+ T cells from the tumor-draining lymph node and spleen generally had very low PD-1 expression (Fig. 5D). Compared to intratumoral PD-1-CD8+ T cells, PD-1+CD8+ T cells from the tumor produced only minimal amounts of IFN-γ after stimulation with PMA and ionomycin, suggesting that these cells are dysfunctional (Fig. 5D). However, in vitro treatment of bulk intratumoral T cells from untreated KitV558Δ/+ mice with anti-PD-1 antibody increased their production of both TNF and IFN-γ (Fig. 5E). In contrast, T cells from the mesenteric lymph node of wild-type mice had little cytokine production at baseline or after PD-1 blockade. Thus, PD-1 blockade preferentially affected tumor-infiltrating T cells compared to T cells from the mesenteric lymph node, which essentially lacked PD-1 expression.

Figure 5. Imatinib modulates IFN-γ–related genes and PD-L1 expression in GIST.

(A) Bar graph showing mRNA levels of IFN-γ–related genes determined by microarray analysis of tumors from KitV558Δ /+ mice treated with imatinib for 1 week. Data are shown as log2 fold change compared to vehicle-treated KitV558Δ /+ mice (3 per group). Bars represent mean. (B) Representative immunohistochemistry with anti-PD-L1 of tumors from KitV558Δ /+ mice treated with vehicle or imatinib for 4 weeks (scale bar, 100 μm). (C) Histograms of PD-1 and PD-L1 expression on tumor cells (CD45-Kit+), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs, CD45+F4/80+CD11b+) and T cell subsets (CD4+ Tconv cells: CD45+CD3+CD4+Foxp3-, Tregs: CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+Foxp3+, and CD8+ T cells: CD45+CD3+CD8+) in GIST-bearing KitV558Δ /+ mice treated with vehicle or imatinib for 1 week (3–5 per group). Representative plots are depicted with isotype control (gray), vehicle (blue) and imatinib (red). (D) Expression of IFN-γ in stimulated CD8+ T cells from spleens, tumor-draining lymph nodes (TdLNs), and tumors from untreated KitV558Δ /+ mice. CD8+ T cells from the indicated tissues were isolated, stimulated in vitro with PMA and ionomycin, then analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) Effect of PD-1 blockade on cytokine production in T cells. T cells were harvested from the mesenteric lymph node (mLN) from B6 mice (WT) or the tumor from untreated KitV558Δ /+ mice and cultured in vitro in the presence of anti-PD-1 (10 μg/ml) or isotype control. After 48 h, culture supernatant was collected and cytokines were measured by cytometric bead array. Data represent mean ± SEM *P < 0.05.

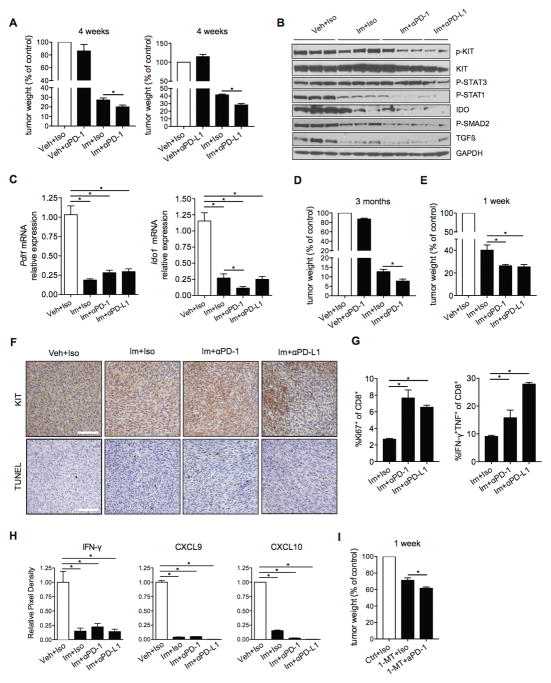

PD-1/PD-L1 blockade enhances the antitumor effects of imatinib in murine GIST

Given the presence of PD-1 and PD-L1 in both human and murine GIST, we hypothesized that blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis would have an antitumor effect. We treated KitV558Δ /+ mice with imatinib or vehicle combined with PD-1 or PD-L1 antibodies or isotype control for 4 weeks. The combination of imatinib and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade was not associated with noticeable toxicity in our model and mice did not show signs of autoimmunity. Notably, anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 altered tumor weight only when combined with imatinib (Fig. 6A). The combination treatment decreased phosphorylated KIT, phosphorylated STAT1, IDO and TGFβ and its upstream mediator phosphorylated SMAD2 (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, Pdl1 and Ido1 mRNA levels were downregulated after 4 weeks of treatment (Fig. 6C). Importantly, the enhanced antitumor effect of imatinib and anti-PD-1 persisted at 3 months of treatment (Fig. 6D), and was detectable as early as 1 week (Fig. 6E). After 1 week of combined treatment, we noticed decreased KIT staining, indicating a reduction of tumor cells, especially in tumors from mice treated with imatinib plus anti-PD-L1, and increased TUNEL staining, indicating increased tumor cell apoptosis (Fig. 6F). There was no change in the frequency of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells or Tregs after 1 or 4 weeks of combination treatment (data not shown). Remarkably, intratumoral CD8+ T cells showed increased proliferation and inflammatory cytokine production upon combination treatment for 1 week compared to imatinib alone (Fig. 6G). In accordance with our observations from the mRNA microarray, IFN-γ protein and 2 of the chemokines it induces, CXCL9 and CXCL10, were downregulated after 1 week of treatment (Fig. 6H). Furthermore, PD-1 blockade combined with the IDO inhibitor 1-MT was more effective after 1 week of treatment in our GIST mouse model than IDO inhibition alone (Fig. 6I). Thus, IDO inhibition (which also occurs after imatinib therapy alone) is sufficient to enable the antitumor effect of anti-PD-1. Taken together, we showed that KIT inhibition combined with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade reduced tumor weight in KitV558Δ /+ mice, which was associated with increased tumor cell apoptosis and enhanced frequency of cytokine-producing CD8+ T cells.

Figure 6. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade enhances the antitumor effects of imatinib in murine GIST.

(A) Tumor weights from KitV558Δ /+ mice (3–5 per group) treated with imatinib (Im) or vehicle (Veh) for 4 weeks. Anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies or their isotypes (Iso) were given on days 0, 4, 8, and 12. Mice were sacrificed at day 28. (B) Western blot of tumor samples from KitV558Δ /+ mice treated as in A. (C) Bulk tumors were analyzed for expression of Pdl1 and Ido1 by real-time PCR. Data are normalized to control. Data represent mean of at least 3 samples ± SEM *P < 0.05. (D) Tumor weights after 3 months of treatment (3–5 mice per group). Antibodies or isotypes were given as in A. Mice were sacrificed at day 90. (E) Tumor weights from KitV558Δ /+ mice (3–5 per group) treated with imatinib for 1 week. Anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies were given on days 0, 2, 4, and 6. Mice were sacrificed at day 7. (F) Tumor KIT and TUNEL staining after 1 week of treatment. Scale bars, 50μm. (G) Percentages of intratumoral CD8+ T cells that were Ki67+ or IFN-γ/TNF–producing intratumoral CD8+ T cells after in vitro stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. Data represent means of 3–4 samples ± SEM *P < 0.05. (H) Cytokine array densitometry of tumors from KitV558Δ /+ mice after 1 week of treatment. (I) Tumor weights from KitV558Δ /+ mice treated with 1-MT for 1 week (3–5 per group). Anti-PD-1 antibody was given as in E. Mice were sacrificed at day 7. All tumor weights are shown normalized to vehicle control.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the PD-1/PD-L1 axis contributes to tumor immune evasion in GIST. Among the inhibitory receptors analyzed on intratumoral T cells in human GIST, PD-1 was expressed at the highest frequency. Notably, the PD-1 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within sensitive and resistant human GISTs had a bimodal distribution, with a distinct population having very high expression, suggesting that a subset of patients might particularly benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. The level of PD-1 expression on intratumoral CD4+ T cells correlated with that on CD8+ T cells within a patient. Furthermore, in patients with multiple tumors, the different tumors had similar amounts of inhibitory receptors on intratumoral T cells, despite differences in tumor location, size, and mitotic rate. This observation does not resolve whether the antitumor immune response is either tumor-driven, despite the known heterogeneity among tumor subclones, or patient-driven, as systemic host factors may be responsible for a consistent T cell response. PD-1 expression has been demonstrated to identify T cells that recognize tumor-specific proteins (26). PD-1+CD8+ T cells accumulated in murine GISTs, but produced less IFN-γ upon in vitro stimulation compared to PD-1−CD8+ T cells, suggesting that PD-1 marks functionally impaired intratumoral T cells in our model. Nevertheless, bulk intratumoral T cells made inflammatory cytokines after treatment with anti-PD-1 in vitro, as did intratumoral CD8+ T cells from KitV558Δ /+ mice that had been treated with anti-PD-1 in vivo.

PD-L1 expression in human GISTs was variable and did not correlate with treatment status, tumor mutation, and tumor size. Tumors with a lower mitotic rate had a very modest correlation with higher PD-L1 expression, which has been suggested by prior data (27). We showed that PD-L1 expression in human GIST was similar between tumor and stromal cells. It is unclear whether PD-L1 expression by either tumor or immune cells is required for response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. In a previous report, a subset of melanoma patients with PD-L1–negative tumors responded to PD-1 blockade, suggesting that PD-L1 expression may not be necessary for response (28). Investigation of this question is hampered by the suboptimal antibodies for PD-L1 immunohistochemistry. In fact, in several human GISTs we found only focal immunostaining despite relatively high PD-L1 mRNA levels.

Multiple mechanisms have been shown to drive PD-L1 expression. First, PD-L1 can be induced by IFN-γ (12, 29). Although human GIST cell lines had low PD-L1 expression IFN-γ treatment markedly increased it, likely through STAT1. IFN-γ generally enhances the inflammatory response, but may also promote immunosuppression by reducing tumor recognition and T cell mediated lysis (30). PD-L1 expression has also been linked to EGFR mutations, PI3K/AKT signaling, and, in BRAF-resistant melanoma cell lines, reactivation of the MAPK pathway (31–33). In GIST, PD-L1 expression may conceivably be induced by other cytokines, signaling pathways, and immune cells within the tumor microenvironment, as well as by IFN-γ. Oncogene inhibition downregulates PD-L1 expression in melanoma cell lines (33, 34). Similarly, in our mouse model, imatinib decreased PD-L1 mRNA, protein, and cell surface expression. In addition, imatinib treatment of GIST cell lines abrogated the effect of IFN-γ on PD-L1 expression. The effects of imatinib were likely mediated by suppression of JAK/STAT and PI3K/AKT, which are both downstream of KIT, and by repression of IFN-γ and IFN-γ–related genes. The reduction in IFN-γ is consistent with the previous finding that imatinib reduced MHC class I expression in human GISTs (35) and our demonstration that imatinib lowered class II in murine and human tumor-associated macrophages in GIST (36).

Tumor cells treated with targeted therapy were recently shown to induce a reactive secretome that promotes the survival of sensitive cells, and the expansion and dissemination of drug-resistant clones (37). This therapeutic obstacle might be overcome by combining targeted therapy with mobilization of the immune system. Indeed, our data demonstrated that anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 in KitV558Δ /+ mice with established tumors increased the effects of imatinib by enhancing CD8+ T cell function, resulting in substantial tumor cell apoptosis. Administered alone, anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 were ineffective. It seems unlikely that pretreatment with the blocking antibodies would further improve the combination of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade and imatinib. Imatinib-induced tumor cell death could sensitize GIST to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade through the release of endogenous tumor antigens that subsequently activate the immune system. However, the rapid tumor response by 1 week makes it more likely that a pre-existing immune response was amplified It does not seem that PD-1 inhibition in our model reduced tumor growth independent of the adaptive immune system, a mechanism recently shown in human melanoma tumor cells, which frequently express PD-1 (38).

The other contributing factor that explains the efficacy of combining imatinib with anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 is the inhibition of IDO. IDO is an enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of the essential amino acid tryptophan to kynurenine, whose metabolites suppress T cells. Previously we showed that imatinib reduces tumor cell production of IDO in our model by decreasing the levels of the transcription factor ETV4, which regulates IDO transcription (6). Recent studies have suggested that elevated expression of metabolic enzymes (e.g. IDO) and inhibitory molecules (e.g. PD-1) is induced by IFN-γ as an adaptive response by the tumor (29, 39). Our data imply that IDO inhibition by imatinib partially accounts for the antitumor efficacy of concomitant PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. This supposition is consistent with a previous report showing that IDO inhibition augmented the efficacy of T cell immunotherapy in B16 melanoma (40). Furthermore, tumor regression after therapeutic PD-1 blockade has been demonstrated to require preexisting CD8+ T cells that are negatively regulated by PD-1/PD-L1-mediated adaptive immune resistance. Response to pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) was associated with higher numbers of CD8+, PD-1+, and PD-L1+ cells in the tumor microenvironment before treatment (41). The combination of imatinib and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade may be most effective in treatment-naïve tumors, which are the most sensitive to oncogene inhibition. Melanomas with high levels of somatic mutations have been shown to be more likely to respond to checkpoint immune blockade (42). However, our data show that murine GIST, which has only one mutation, responds to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in the setting of tyrosine kinase inhibition.

In conclusion, PD-1 was expressed at high levels on tumor-infiltrating T cells in human GIST, while PD-L1 levels were variable. In a mouse model of GIST, anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 had no antitumor effect when used alone, but did increase the efficacy of imatinib. The mechanism involved a reduction of IDO levels and an increase in CD8+ T cell function. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade is a promising strategy to improve the effects of targeted therapy in GIST.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Although GISTs are often initially sensitive to imatinib or other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, resistance generally develops, necessitating additional therapeutic strategies. There has not been any improvement in the first-line therapy for GIST since imatinib was approved in 2002. Immunotherapy is being tested in a variety of cancers. Our findings provide new insights into the combination of tyrosine kinase inhibition and immunotherapy and provide a strong incentive to clinically combine imatinib and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 in GIST. Furthermore, our data challenge the current notion that immunotherapy is effective only in tumors with a high number of mutations, since there is only one mutation in our mouse model, as is typical in human GIST.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: The investigators were supported by NIH grants R01 CA102613 and T32 CA09501, Cycle for Survival, Swim Across America, Stephanie and Fred Shuman through the Windmill Lane Foundation, and David and Monica Gorin (RPD); GIST Cancer Research Fund (RPD and CRA); F32 CA162721 and the Claude E. Welch Fellowship from the Massachusetts General Hospital (TSK); F32 CA186534 (JQZ); P01 CA47179 (CRA), and P50 CA140146-01 (CRA and PB). The Molecular Cytology and Flow Cytometry Core Facilities were supported by Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

We are grateful to the Tissue Procurement Service for assistance in the acquisition of human tumor specimens. We thank members of the Sloan Kettering Institute Laboratory of Comparative Pathology, Molecular Cytology, Flow Cytometry, and Pathology Core Facilities, Colony Management Group, and Research Animal Resource Center. We thank Lieping Chen for giving us the murine anti-human PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (clone 5H1) and Jacqueline Bromberg for providing the JAK inhibitor pyridine 6. We thank Russell Holmes for logistical and administrative support.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, Hashimoto K, Nishida T, Ishiguro S, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279:577–80. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A, McGreevey L, Chen CJ, Joseph N, et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 2003;299:708–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1079666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joensuu H, DeMatteo RP. The management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a model for targeted and multidisciplinary therapy of malignancy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:247–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-043010-091813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanke CD, Rankin C, Demetri GD, Ryan CW, von Mehren M, Benjamin RS, et al. Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:626–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verweij J, Casali PG, Zalcberg J, LeCesne A, Reichardt P, Blay JY, et al. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1127–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balachandran VP, Cavnar MJ, Zeng S, Bamboat ZM, Ocuin LM, Obaid H, et al. Imatinib potentiates antitumor T cell responses in gastrointestinal stromal tumor through the inhibition of Ido. Nat Med. 2011;17:1094–100. doi: 10.1038/nm.2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmadzadeh M, Johnson LA, Heemskerk B, Wunderlich JR, Dudley ME, White DE, et al. Tumor antigen-specific CD8 T cells infiltrating the tumor express high levels of PD-1 and are functionally impaired. Blood. 2009;114:1537–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fourcade J, Sun Z, Benallaoua M, Guillaume P, Luescher IF, Sander C, et al. Upregulation of Tim-3 and PD-1 expression is associated with tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cell dysfunction in melanoma patients. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2175–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baitsch L, Baumgaertner P, Devêvre E, Raghav SK, Legat A, Barba L, et al. Exhaustion of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells in metastases from melanoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2350–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI46102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong H, Zhu G, Tamada K, Chen L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nat Med. 1999;5:1365–9. doi: 10.1038/70932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: A potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, Activity, and Immune Correlates of Anti–PD-1 Antibody in Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDermott DF, Drake CG, Sznol M, Choueiri TK, Powderly JD, Smith DC, et al. Survival, Durable Response, and Long-Term Safety in Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Receiving Nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQM, Hwu W-J, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and Activity of Anti–PD-L1 Antibody in Patients with Advanced Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, Fine GD, Hamid O, Gordon MS, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powles T, Eder JP, Fine GD, Braiteh FS, Loriot Y, Cruz C, et al. MPDL3280A (anti-PD-L1) treatment leads to clinical activity in metastatic bladder cancer. Nature. 2014;515:558–62. doi: 10.1038/nature13904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:122–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu W-J, Kefford R, et al. Safety and Tumor Responses with Lambrolizumab (Anti–PD-1) in Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taguchi T, Sonobe H, Toyonaga S, Yamasaki I, Shuin T, Takano A, et al. Conventional and molecular cytogenetic characterization of a new human cell line, GIST-T1, established from gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Lab Invest. 2002;82:663–5. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim TS, Cavnar MJ, Cohen NA, Sorenson EC, Greer JB, Seifert AM, et al. Increased KIT inhibition enhances therapeutic efficacy in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2350–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao SP, Mark KG, Leslie K, Pao W, Motoi N, Gerald WL, et al. Mutations in the EGFR kinase domain mediate STAT3 activation via IL-6 production in human lung adenocarcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3846–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI31871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sommer G, Agosti V, Ehlers I, Rossi F, Corbacioglu S, Farkas J, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in a mouse model by targeted mutation of the Kit receptor tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6706–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037763100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen NA, Zeng S, Seifert AM, Kim TS, Sorenson EC, Greer JB, et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of KIT Activates MET Signaling in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2061–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wherry EJ, Ha S-J, Kaech SM, Haining WN, Sarkar S, Kalia V, et al. Molecular Signature of CD8+ T Cell Exhaustion during Chronic Viral Infection. Immunity. 2007;27:670–84. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gros A, Robbins PF, Yao X, Li YF, Turcotte S, Tran E, et al. PD-1 identifies the patient-specific CD8+ tumor-reactive repertoire infiltrating human tumors. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2246–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI73639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertucci F, Finetti P, Mamessier E, Pantaleo MA, Astolfi A, Ostrowski J, et al. PDL1 expression is an independent prognostic factor in localized GIST. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1002729. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2014.1002729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M, Mortier L, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spranger S, Spaapen RM, Zha Y, Williams J, Meng Y, Ha TT, et al. Up-Regulation of PD-L1, IDO, and Tregs in the Melanoma Tumor Microenvironment Is Driven by CD8+ T Cells. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:200ra116–200ra116. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beatty GL, Paterson Y. IFN-gamma can promote tumor evasion of the immune system in vivo by down-regulating cellular levels of an endogenous tumor antigen. J Immunol. 2000;165:5502–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akbay EA, Koyama S, Carretero J, Altabef A, Tchaicha JH, Christensen CL, et al. Activation of the PD-1 Pathway Contributes to Immune Escape in EGFR-Driven Lung Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1355–63. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsa AT, Waldron JS, Panner A, Crane CA, Parney IF, Barry JJ, et al. Loss of tumor suppressor PTEN function increases B7-H1 expression and immunoresistance in glioma. Nat Med. 2007;13:84–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang X, Zhou J, Giobbie-Hurder A, Wargo J, Hodi FS. The activation of MAPK in melanoma cells resistant to BRAF inhibition promotes PD-L1 expression that is reversible by MEK and PI3K inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:598–609. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atefi M, Avramis E, Lassen A, Wong DJ, Robert L, Foulad D, et al. Effects of MAPK and PI3K pathways on PD-L1 expression in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:3446–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rusakiewicz S, Semeraro M, Sarabi M, Desbois M, Locher C, Mendez R, et al. Immune infiltrates are prognostic factors in localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3499–510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavnar MJ, Zeng S, Kim TS, Sorenson EC, Ocuin LM, Balachandran VP, et al. KIT oncogene inhibition drives intratumoral macrophage M2 polarization. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2873–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Obenauf AC, Zou Y, Ji AL, Vanharanta S, Shu W, Shi H, et al. Therapy-induced tumour secretomes promote resistance and tumour progression. Nature. 2015;520:368–72. doi: 10.1038/nature14336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleffel S, Posch C, Barthel SR, Mueller H, Schlapbach C, Guenova E, et al. Melanoma Cell-Intrinsic PD-1 Receptor Functions Promote Tumor Growth. Cell. 2015;162:1242–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taube JM, Anders RA, Young GD, Xu H, Sharma R, McMiller TL, et al. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-h1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:127ra37. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmgaard RB, Zamarin D, Munn DH, Wolchok JD, Allison JP. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is a critical resistance mechanism in antitumor T cell immunotherapy targeting CTLA-4. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1389–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, Shintaku IP, Taylor EJ, Robert L, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568–71. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, Yuan J, Zaretsky JM, Desrichard A, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2189–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.