Summary

Over the years the treatment of scalds in our centre has changed, moving more towards the use of biological dressings (xenografts). Management of scalds with mid dermal or deep dermal injuries differs among centers using different types of dressings, and recently biological membrane dressings were recommended for this type of injury. Here we describe differences in treatment outcome in different periods of time. All patients with scalds who presented to the Linkoping Burn Centre during two periods, early (1997-98) and later (2010-12) were included. Data were collected in the unit database and analyzed retrospectively. A lower proportion of autograft operations was found in the later period, falling from 32% to 19%. Hospital stay was shorter in the later period (3.5 days shorter, p=0.01) and adjusted duration of hospital stay/TBSA% was shorter (1.2 to 0.7, p=0.07). The two study groups were similar in most of the studied variables: we could not report any significant differences regarding outcome except for unadjusted duration of hospital stay. Further studies are required to investigate functional and aesthetic outcome differences between the treatment modalities.

Keywords: scalds,; burns,; outcome,; duration of stay

Abstract

Le traitement des brûlures par liquides chauds a changé avec le temps, évoluant de plus en plus vers l’usage des pansements biologiques (xénogreffes). La prise en charge de ce type de brûlures (de profondeur moyenne ou profonde) diffère suivant les centres qui utilisent différents types de pansements et plus récemment, les membranes biologiques ont été recommandées pour ce type de traumatisme. Dans cette étude, nous décrivons les résultats thérapeutiques obtenus au cours de différentes périodes. Tous les patients avec des brûlures par liquides chauds admis au Centre de brûlés Linkoping pendant deux périodes d’abord de 1997-1998 et plus tard de 2010 à 2012 ont été inclus. Les résultats de notre banque de données ont été recueillis et analysés de façon rétrospective. Une proportion basse de greffes cutanées a été retrouvée dans la dernière période passant de 32% à 19%. Le séjour à l’hôpital a été également raccourci dans cette période (3,5 jours en moins, p= 0,01) et la durée d’hospitalisation en rapport avec l’étendue a diminué (1,2 à 0,7, p=0,07). Les résultats dans les deux groupes étaient semblables dans la plupart des variables étudiées: nous ne trouvons pas de différence significative sur le plan des résultats, excepté pour la durée d’hospitalisation. De nouvelles études sont nécessaires pour évaluer les divers résultats fonctionnels et esthétiques en fonction des modalités thérapeutiques.

Introduction

Scalds are not the most lethal type of burn but they are one of the most common, and are a leading cause of morbidity and admission to hospital globally, particularly among young children (< 2 years old). Some authors reported that the majority of children with scald burns were admitted with burns of <10% TBSA,1 while others reported that some scald patients needed surgical operations.2,3 A Swedish study showed that those at greatest risk of scalds are infants aged 13-15 months, particularly in disadvantaged families.4 Otherwise, most scalds are seen in young working men, and elderly and disabled people. 5,6

Biological dressings (xenografts and allografts) are an integral part of modern burn care. Viable allografts are often regarded as the “gold standard” in temporary skin coverage because they possess many of the qualities of the “ideal” burn dressing.7,8 However, supplies may be limited due to local cultural factors, especially in developing countries where there are cultural and religious constraints on the use of cadaveric skin and xenografts in burn treatment.9

Several studies have reported the use of xenografts as burn dressings in superficial second-degree burns,10-12 but we know of no specific study that has shown their full effect. Some have discussed the potential hazards of the transmission of viral infections when using pig skin.13 Other studies have reported surgical excision and skin grafts for scalds.14

Inspired by Still et al.,12 we changed the policy in our burn centre to the regular use of xenografts. This was expected to allow more outpatient-based care of scalds. We evaluated outcome in terms of duration of hospital stay, and compared the results with those of conventional dressing use.

Methods

Our study sample included all patients treated for scalds at the national burn centre in Linkoping, Sweden, over two different periods: 1997-98 (validated medical data registry was available), when the unit was not a national burn centre, and 2010-12, after the centralisation of burn care in Sweden. No patient treated within these two periods was excluded. The hospital had a primary catchment of 244,000 inhabitants, which was then extended nationwide in the later period, when patients could be local residents or referrals, and the severity of scalds varied accordingly. Referrals were admitted in line with the national guidelines for burn care.

Current admission criteria are: deep dermal and full thickness burns regardless of TBSA%; superficial burns of more than 10% TBSA; burns of more than 5% TBSA in children under 3 years old. Furthermore, patients (adults and children) were admitted if they had burns that involved the face, the genitalia or the perineum, the hands or feet, or main joints. They were also admitted if they had co-existing chronic diseases, and associated injuries or inhalational injury together with the scald.

Discharge criteria are: stable vital signs, controlled pain, no need for intravenous fluids or antibiotics, and if no surgical intervention was planned within 24 hours. According to our protocol, patients (adults/children) who fit these criteria can be treated on an out-patient basis until the wound is fully healed.

Data were collected retrospectively from medical records. Details of scalded patients were taken from the database at the burn unit.15 At admission, the severity of the wound was assessed by a plastic surgeon. The scalds were initially treated as superficial dermal burns, expected to heal spontaneously within two weeks, therefore they were treated conservatively for two weeks. Superficial dermal burns heal with time, while deep dermal burns and full thickness burns require surgical management with revision and skin graft. The burn was classified according to appearance, capillary refilling and sensory function of the burned areas, and was recorded in detailed Lund & Browder charts. Data retrieved included age, sex, date of injury, TBSA%, depth of burn, details of diagnosis, clinical management (operative or conservative, first operation day, excised area (BSA), operating time in minutes) and duration of hospital stay. The patients were usually discharged shortly before their burn wounds were fully healed, when their health care providers could offer them the necessary medical care on an out-patient basis. Duration of hospital stay/TBSA; and duration of hospital stay/excised area were also calculated.

The criteria followed to admit patients to the centre in the early period were similar to the criteria used in the later period: the difference was that some hospitals kept in patients with small- and medium-sized burns. The burnt area was washed and dressed with Vaseline™ gauze or other types of non-adherent gauze every second day. For deeper scalds, silver sulphadiazine (Flamzine®, Smith & Nephew) was used as a daily dressing and follow up was done in hospital. Either the burn healed, or deeper sites were marked out for autografting. In the early period, the discharge criteria were more conservative and patients were kept in hospital for longer durations.

When a patient was admitted in the later period, second and third degree burns were covered with a Mediskin® xenograft as our standard of care procedure (Molnlycke, Health Care AB, Gothenburg, Sweden) after the surface was thoroughly cleaned under general anaesthesia or sedation in the operating theatre. The xenografts were kept in place with biological glue (DERMABOND ADVANCED® Topical Skin Adhesive, Ethicon or Artiss® Baxter). The wounds were then covered with a nylon mesh and wrapped with normal sterile gauze followed by elastic stockings or elastic bandages. Xenograft application is a surgical intervention according to the ICD-10 system, but only surgical excisions and skin grafts of burn wounds were counted in the analysis. The outer dressings were changed every other day and the xenografts were monitored to detect any suspected collection of fluids or pus under them. Dried edges were removed until the wound had fully healed or full thickness was demarcated.

The wounds were examined for up to 2 weeks and, if demarcated, any persisting deep wounds were excised and covered with autologous split thickness skin grafts. In cases where xenografts were no longer adherent to a wound bed that had been showing signs of infection or delayed healing or both, silicone foam dressing containing ionic silver was applied before excision (Mepilex Border® Mepilex Ag, Mölnlycke Health Care, Sweden). Swabs were taken for culture when the patient was admitted, and at regular intervals determined by the attending surgeon.

We divided both study groups into categories for children and adults. Age groups included patients aged 0-17.9 years (children), 18-39 years, 40-60 years and over 60 years; TBSA% groups were 0-9.9%, 10-19.9%, 20-29.9% and over 30%, conservatively managed or surgically managed. The total surface area of an excised burn was calculated as the sum of all operations, and the method was either operation or conservative treatment. The early period was coded “0” and the later one was coded “1”.

Data analysis and statistics

Data are presented as mean (SD) or as median (IQR) and by age range. The differences between the groups were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U or Chi Square tests as appropriate.

The multiple regression model included duration of hospital stay as a dependent variable, and age group (0-12 years as a reference group), TBSA% group (0-9.9% TBSA as reference group) and total excised surface area of the burn (%) as independent variables. Data were analysed by time, age group and method of treatment (operative/conservative).

Independent variables were included in the stepwise analysis, and clinical variables that had contributed significantly to the final result were retained in the model.

Data were analysed with the help of Stata (Stata version 12.0, StataCorp, Texas, USA). Probabilities of less than 0.05 were accepted as significant.

Results

Of the 541 admissions (all burn injuries in both periods), 135 (25%) patients (scalds) were included in the study. Thirtyeight patients were admitted during the early period: 12 of them were adults and 26 were children. A total of 26 patients were managed conservatively and 12 required an autograft. Ninetyseven patients were admitted during the later period: 23 adults and 74 children. A total of 79 required conservative treatment and 18 required an autograft. There were no deaths (Table I).

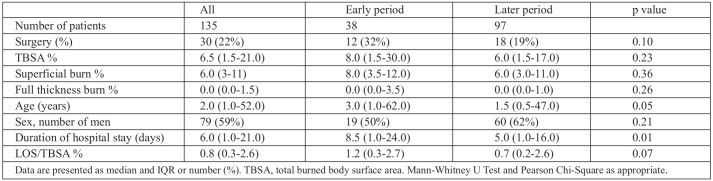

Table I. The different patient groups based on the treatment plan.

Median TBSA% was 8% in the early period and 6% in the later period (p=0.23); superficial burns had a similar pattern in both periods (p=0.36), while median full thickness burns was 0 in both periods (p=0.26). However, the IQR showed a tendency for bigger FTB% in the early period. Median age was 3 years in the early period and 1.5 years in the later (p=0.05). There was no difference between frequency of men and women in the early period (50% and 62%, p=0.21) (Table II). Duration of hospital stay was 3.5 days longer in the early period (p=0.01) after adjusting for TBSA%: there was, however, no difference (1.2 and 0.7, p=0.07) (Table II).

Table II. Details of the study group.

Hospital stay of children was halved during the later period (median 8 days for the early period and 4.5 days for the later period, p=0.02). However, other variables such as TBSA%, age and duration of hospital stay/TBSA% did not differ. Among adults, duration of hospital stay decreased from 12.5 to 8 days, but this was not significantly different.

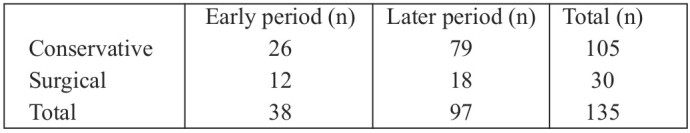

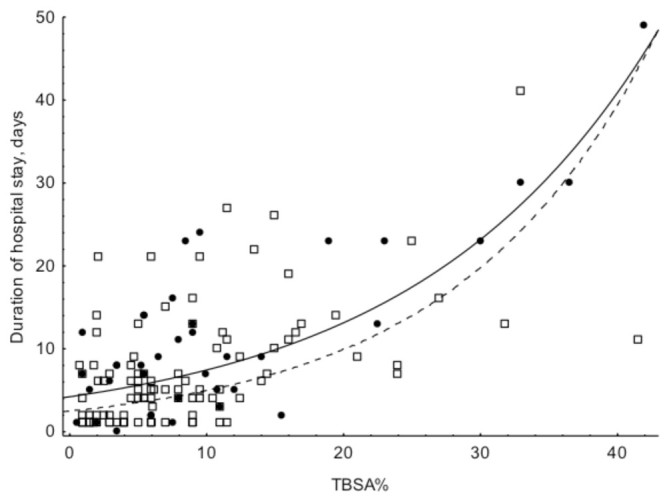

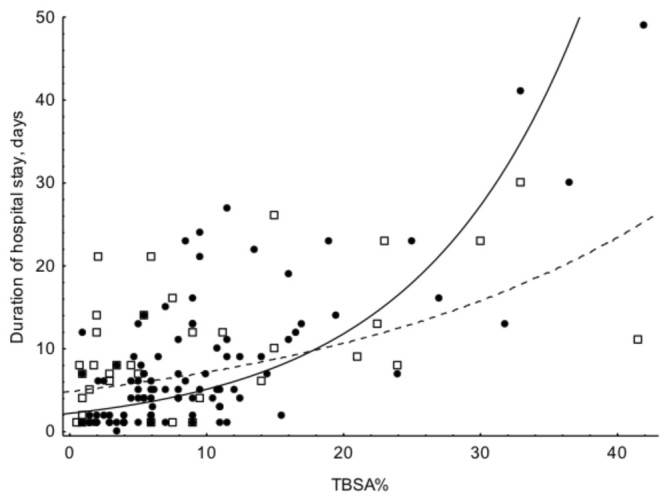

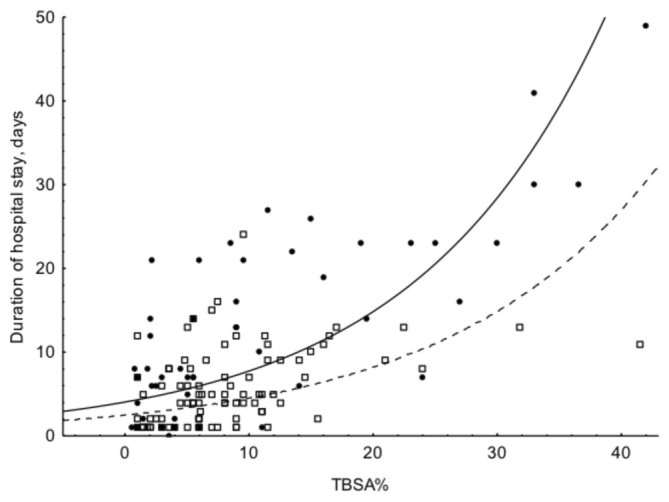

Fig. 1 shows the similar association pattern between duration of hospital stay and TBSA% in both periods. Most of the patients in both periods had TBSA% in the range of 0-15%, staying between 1 to 25 days in the hospital. Fig. 2 shows the differences between adults and children, with longer duration of stay for children with bigger burns. Fig. 3 shows longer duration of hospital stay in the surgically managed group.

Fig. 1. The association between duration of hospital stay and TBSA% during the two periods A and B. Solid circles and solid line = period A, open boxes and dotted lines = period B. The fitted lines are exponential. LOS A = 4.2252*exp(0.0568*x), LOS B = 2.5058*exp(0.0689*x) TBSA% - LOS A: y = 2.6901 + 0.8066*x; r = 0.79; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.63 TBSA% - LOS B: y = 3.0889 + 0.4936*x; r = 0.53; p <0.001; r2 = 0.28.

Fig. 2. The association between duration of hospital stay and TBSA. Solid circles and solid line = children, open boxes and dotted lines = adults. The fitted lines are exponential. LOS Children = 2.2202*exp(0.0836*x), LOS Adults = 4.8619*exp(0.0393*x) TBSA% - LOS Children: y = 0.5349 + 0.8135*x; r = 0.73; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.53 TBSA% - LOS Adults: y = 6.7765 + 0.3571*x; r = 0.49; p = 0.003; r2 = 0.24<.

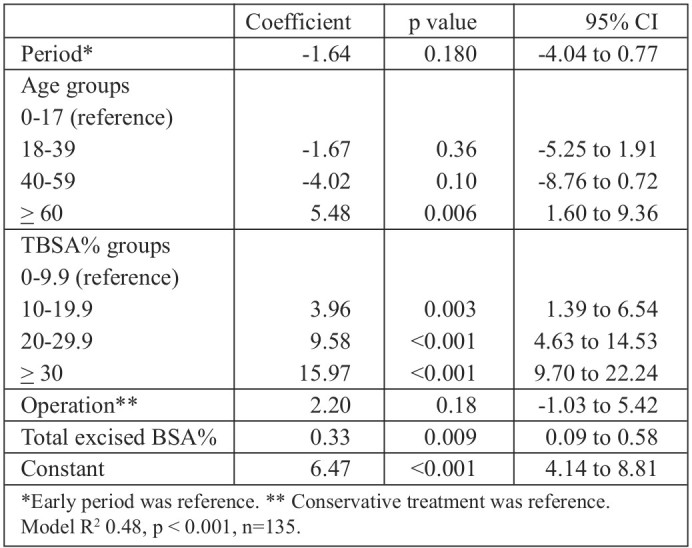

Table III shows the results of a multivariable regression model for duration of hospital stay, adjusted for age, TBSA%, treatment modality (conservative treatment as reference), total excised BSA% and time period, which showed that duration of hospital stay was longer in the older age group (> 60 years) and increased with increasing TBSA% and total excised BSA%.

Table III. Duration of hospital stay, multivariable regression.

Fig. 3. The association between duration of hospital stay and TBSA%. Solid circles and solid line = surgically managed group, open boxes and dotted lines = conservatively managed group. The fitted lines are exponential. TBSA% - LOS Surgical: y = 4.4541 + 0.8005*x; r = 0.78; p = 0.0000 TBSA% - LOS conservative: y = 3.4873 + 0.2836*x; r = 0.41; p = 0.00009.

Discussion

We compared two time periods during which different treatments for scalds were used, and we found that duration of hospital stay was shorter in the later period, which may have been because patients could be discharged to continue their wound care as outpatients. The use of xenografts as dressing in the later period probably helped to lower the patients’ pain levels.16 It has also been reported to speed up the healing process and, importantly, is associated with lower infection rates and better aesthetic outcomes.17 When we analyzed the data for adults and children separately, duration of hospital stay/TBSA% for adults did not alter, but there was a tendency for a shorter hospital stay/TBSA% in the children’s group. Patients who had operations didn’t stay in hospital significantly longer than those who were managed conservatively in the two periods, as shown in the regression model.

Most scalds are superficial burns that spontaneously heal without the need for excisions and skin graft: however, this is not true for all patients. Several authors have reported a considerable proportion of surgical revisions and autograft in this group of patients.18,19 This is in line with the proportion of patients in both study periods who required autografts.

The treatment protocol for scald burns in our centre is based on conservative treatment initially, unless they have early demarcated full thickness injuries. The waiting time is two weeks until demarcation of the wound. Authors have supported leaving more dermis rather than over-excise the dermis when doing early excision and skin grafting based on the fact that the scar outcome is better using this method.20 A study on hypertrophic scars after scald burns showed minimal rates in patients operated on up to 21 days after injury19 which supports our treatment plan. This is in contrast to the situation with other types of burns like flame burns where early excision and skin grafting is a better solution, as reported by Herndon et al..21

The decrease in the proportion of autografts in the later period, although not significant, may indicate an improvement in treatment strategies. This can be attributed to the use of a more conservative plan in the later period, expecting spontaneous healing.

Most of the admissions for scalds in both periods were toddlers between 0-2 years and fewer adults, which is in line with many studies.4 Most accidents occurred in the home despite more community-based prevention programs. However, it is well known that employing effective prevention programs for scalds is problematic,22-24 which is supported by our data. Unfortunately, we know of no sound epidemiological data that evaluates the effect of community-based interventions and legislative changes, such as lowering the water temperature of taps in the home.3,253,25 Furthermore, in both periods more men were injured, which also corresponds with the results of other studies.23,24

Limitations

One of the limitations of the study is that hospital stay duration is not equal to healing time: however, it represents a significant proportion of that time and can therefore be used as a generalized indicator for the outcome of the burn care process.26

As the study data were collected retrospectively from the patient’s registry, including all patients with scalds with variable depth and different treatment methods, they lacked the homogeneity that distinguishes prospective studies with their planned collection of data. The small number of subjects is another limitation, although all patients with scalds were included, which makes it representative of a Scandinavian burn centre.

The database did not include records on functional and aesthetic outcome for the study group. We are conducting prospective studies in our centre that address these important outcome measures

Conclusion

The two study groups were similar in most of the studied variables. We could not report significant differences regarding outcome except for unadjusted duration of hospital stay. Further studies are required to investigate functional and aesthetic outcome differences between the treatment modalities

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interestWe have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Duke J, Wood F, Semmens J, Edgar DW. A study of burn hospitalizations for children younger than 5 years of age: 1983-2008. Pediatrics. 2011;127:E971–E977. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papp A, Rytkonen T, Koljonen V, Vuola J. Paediatric ICU burns in Finland 1994-2004. Burns. 2008;34:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowell G, Quinlan K, Gottlieb LJ. Preventing unintentional scald burns: moving beyond tap water. Pediatrics, 2008;122:799–804. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hjern A, Ringback-Weitoft G, Andersson R. Socio-demographic risk factors for home-type injuries in Swedish infants and toddlers. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90:61–68. doi: 10.1080/080352501750064897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chipp E, Walton J, Gorman DF. A 1 year study of burn injuries in a British Emergency Department. Burns. 2008;34:516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone M, Ahmed J, Evans J. The continuing risk of domestic hot water scalds to the elderly. Burns. 2000;26:347–350. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pruitt BA, Jr, Curreri PW. The burn wound and its care. Arch Surg. 1971;103:461–468. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1971.01350100055010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vloemans AF, Hermans MH, van der Wal MB, Liebregts J. Optimal treatment of partial thickness burns in children: a systematic review. Burns. 2014;40:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maral T, Borman H, Arslan H, Demirhan B. Effectiveness of human amnion preserved long-term in glycerol as a temporary biological dressing. Burns, 1999;25:625–635. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selig HF, Lumenta DB, Giretzlehner M, Jeschke MG. The properties of an “ideal” burn wound dressing - what do we need in daily clinical practice? Results of a worldwide online survey among burn care specialists. Burns. 2012;38:960–966. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansen LA, Hynes SL, Macadam SA, Papp A. Reduced length of stay in hospital for burn patients following a change in practice guidelines: financial implications. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:E275–E279. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31824d1acb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Still J, Donker K, Law E, Thiruvaiyaru D. A program to decrease hospital stay in acute burn patients. Burns. 1997;23:498–500. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(97)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boneva RS, Folks TM. Xenotransplantation and risks of zoonotic infections. Ann Med. 2004;36:504–517. doi: 10.1080/07853890410018826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunne JA, Rawlins JM. Early paediatric scald surgery - a cost effective dermal preserving surgical protocol for all childhood scalds. Burns. 2014;36:777–778. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sjoberg F, Danielsson P, Andersson L, Steinwall I. Utility of an intervention scoring system in documenting effects of changes in burn treatment. Burns. 2000;26:553–559. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elmasry M, Steinvall I, Thorfinn J, Abbas A. Treatment of children with scalds by xenografts: report from a Swedish burn centre. J Burn Care Res. 2015 doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Troy J, Karlnoski R, Downes K, Brown KS. The Use of EZ Derm(R) in Partial-Thickness Burns: An Institutional Review of 157 Patients. Eplasty, 2013;13:E14–E14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riedlinger DI, Jennings PA, Edgar DW, Harvey JG. Scald burns in children aged 14 and younger in Australia and New Zealand - an analysis based on the Burn Registry of Australia and New Zealand (BRANZ) Burns. 2015;41:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cubison TC, Pape SA, Parkhouse N. Evidence for the link between healing time and the development of hypertrophic scars (HTS) in paediatric burns due to scald injury. Burns. 2006;32:992–999. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cubison TC, Pape SA, Jeffery SL. Dermal preservation using the Versajet hydrosurgery system for debridement of paediatric burns. Burns. 2006;32:714–720. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herndon DN, Barrow RE, Rutan RL, Rutan TC. A comparison of conservative versus early excision. Therapies in severely burned patients. Ann Surg. 1989;209:547–552. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198905000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cason CG. A study of scalds in Birmingham. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:690–692. doi: 10.1177/014107689008301106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duke J, Wood F, Semmens J, Spilsbury K. A 26-year populationbased study of burn injury hospital admissions in Western Australia. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32:379–386. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318219d16c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harvey LA, Poulos RG, Finch CF, Olivier J. Hospitalised hot tap water scald patients following the introduction of regulations in NSW, Australia: who have we missed? Burns. 2010;36:912–919. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spallek M, Nixon J, Bain C, Purdie DM. Scald prevention campaigns: do they work? J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:328–333. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0B013E318031A12D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hussain A, Dunn DK. Predicting length of stay in thermal burns: a systematic review of prognostic factors. Burns. 2013;39:1331–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]