Abstract

Objective To examine the association between the presence of individual principal investigators’ financial ties to the manufacturer of the study drug and the trial’s outcomes after accounting for source of research funding.

Design Cross sectional study of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Setting Studies published in “core clinical” journals, as identified by Medline, between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2013.

Participants Random sample of RCTs focused on drug efficacy.

Main outcome measure Association between financial ties of principal investigators and study outcome.

Results A total of 190 papers describing 195 studies met inclusion criteria. Financial ties between principal investigators and the pharmaceutical industry were present in 132 (67.7%) studies. Of 397 principal investigators, 231 (58%) had financial ties and 166 (42%) did not. Of all principal investigators, 156 (39%) reported advisor/consultancy payments, 81 (20%) reported speakers’ fees, 81 (20%) reported unspecified financial ties, 52 (13%) reported honorariums, 52 (13%) reported employee relationships, 52 (13%) reported travel fees, 41 (10%) reported stock ownership, and 20 (5%) reported having a patent related to the study drug. The prevalence of financial ties of principal investigators was 76% (103/136) among positive studies and 49% (29/59) among negative studies. In unadjusted analyses, the presence of a financial tie was associated with a positive study outcome (odds ratio 3.23, 95% confidence interval 1.7 to 6.1). In the primary multivariate analysis, a financial tie was significantly associated with positive RCT outcome after adjustment for the study funding source (odds ratio 3.57 (1.7 to 7.7). The secondary analysis controlled for additional RCT characteristics such as study phase, sample size, country of first authors, specialty, trial registration, study design, type of analysis, comparator, and outcome measure. These characteristics did not appreciably affect the relation between financial ties and study outcomes (odds ratio 3.37, 1.4 to 7.9).

Conclusions Financial ties of principal investigators were independently associated with positive clinical trial results. These findings may be suggestive of bias in the evidence base.

Introduction

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the most reliable form of evidence in evaluating the safety and efficacy of drugs.1 Because results of RCTs shape the evidence base, objectivity in the conduct of clinical trials has important implications for clinical practice and the health and safety of patients.2 However, critics worry that involvement of the pharmaceutical industry may bias the design and interpretation of RCTs.2 3 4 5 In a 2002 survey of 3247 National Institutes of Health scientists, 15.5% admitted to changing the design, methods, or results of a study in response to pressure from a funding source.6 A systematic review of the role of funding on study outcome showed that industry funded studies were more likely than non-industry funded studies to have positive efficacy results (risk ratio 1.24, 95% confidence interval 1.14 to 1.35).7 In addition, industry can subtly influence the conduct of RCTs through financial means other than study funding, including paid consultancy fees and honorariums to physicians.8 9 Such relationships may alter physicians’ perceptions of the company’s products in a favorable light.5 10

Relationships with industry are common among investigators, raising concerns about the effect that financial ties between researchers and industry may have on the evidence base.11 12 In recent years, these concerns have led to calls for transparent reporting of these relationships.13 As a result, many journals now require authors to report their financial ties by using the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ (ICMJE) disclosure form of competing interests.14 The ICMJE recommends that all trials should be pre-registered in databases such as clinicaltrials.gov to minimize publication bias and increase transparency around trial conduct.15 However, not all journals enforce the recommendations.16 Even when trials are registered, the lack of publication of negative trials can diminish the effect of these policies.4

The movement towards transparency provides an opportunity to examine the extent to which investigators’ financial ties are associated with positive study outcomes. Several studies have examined this relation.17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 However, in most of these studies individual investigators’ financial ties were not disentangled from the funding source for the study. These two variables, although related, are different. Funding is awarded to institutions and represents professional gain, not personal financial gain. In addition, most previous studies have been limited to one specialty,17 18 19 20 21 drug type,22 23 or journal.24 25 Some studies have found a positive association between investigators’ ties and outcomes,19 20 21 23 24 25 and others have found no association,17 18 22 although some negative studies may have been insufficiently powered. We examined the relation between financial ties with industry of principal investigators and study outcome across a random sample of RCTs published in 2013, which represents a cross section of the evidence base. We specifically focused on RCTs that examined the efficacy of drugs, because these studies have a high impact on both clinical practice and healthcare costs. We hypothesized that principal investigators’ financial ties with industry would be independently associated with positive study outcomes.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched Medline for RCTs published between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2013 in “core clinical” journals, as identified by Medline, and limited to English language, human subjects, and titles with available abstracts. Our search yielded 2851 papers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible studies were RCTs evaluating the efficacy of drug interventions. We included studies in which the drug of interest was specified (for example, to determine whether eritoran, a TLR4 antagonist, would significantly reduce sepsis induced mortality)26 and excluded head-to-head studies in which the drug of interest was not specified in the paper or in clinicaltrials.gov, because we would be unable to determine whether the study was positive or negative. We excluded non-drug studies, such as studies of devices, supplements, and biomarkers. We also excluded non-primary studies, which included meta-analyses, subgroup analyses, and follow-up studies. We excluded studies without an identifiable funding source. We also excluded studies that did not have searchable financial ties because the manufacturer of the drug of interest was unclear.

Patient involvement

We did not include patients in this study. Our focus was published RCTs. Patients were not involved in any part of the research process.

Preliminary screen and sample size calculation

The 2851 titles and abstracts identified in the search were screened by one of four non-clinician abstractors (AA, RA, SS, AW) for possible relevance. Of the 1101 potentially relevant studies identified, we used a random number generator to select 250 for review. We did a κ test on a sample of 20 studies to determine the strength of the inter-rater agreement on study inclusion. κ was 0.87 (RA/AW) and 0.69 (AA/SS), indicating a high level of agreement for each pair.

In the preliminary review, 87 of 250 papers met the inclusion criteria. We determined the prevalence of financial ties among principal investigators in this initial sample (financial ties were present in 78% of studies with a positive outcome and 59% of those with a negative outcome). On the basis of the prevalence of financial ties in positive and negative studies, we determined that we needed a total of at least 184 papers that met inclusion criteria to test our hypothesis. Using a random number generator, we randomly selected an additional 396 papers for full text review, of which an additional 148 studies were identified for inclusion. A total of 235 papers were identified for possible inclusion by non-clinician abstractors.

Final sample

All 235 papers identified in the preliminary assessment were independently reviewed by two clinician reviewers (SK and DK) for inclusion. Disagreement on inclusion was resolved by discussion. A total of 45 papers were excluded in this stage.

Main outcome variable

We focused on the results section of each paper to identify outcomes. The primary efficacy outcome was the outcome of interest and had to be specified in the trial publication or on clinicaltrials.gov. We defined the study outcome as positive if the hypothesis was supported for the primary efficacy outcome of the study and negative if it was not. For superiority studies, the study outcome was defined as positive if the drug of interest was statistically superior to the control (eg, P<0.05). For non-inferiority studies, the study outcome was defined as positive if the drug of interest was not significantly worse than the control (statistically non-significant difference). In studies with multiple primary efficacy outcomes, we considered the study to be positive if at least one efficacy outcome was positive for superiority studies and not significantly different from the control in non-inferiority studies. For the five papers that included multiple studies, we abstracted data on the outcome for each study separately. Study outcomes were assessed independently and in duplicate. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Main independent variable

We searched for financial ties among principal investigators, who we defined as the first author and senior author (last author) of each paper because these authors are generally most involved in major decisions about studies. If a study specified additional authors as first authors or senior authors, we included them all and considered them all to be principal investigators. We defined a financial tie as the direct compensation of a principal investigator by the manufacturer of the drug of interest in the form of advisor/consultancy payments, employee relationships, honorariums, speaker’s fees, stock ownerships, and travel/meal fees. We categorized papers in which the financial tie was not specified (eg, “financial interest with X company”) as “type not specified.” We also considered a financial tie to be present if the principal investigator was a named inventor of a patent related to the publication.

Financial ties were limited to the drug company that manufactured the drug and did not include any parent company of the manufacturer. For the few papers in which the manufacturer was not disclosed in the publication, we searched clinical trial registries and Google to identify the manufacturer. The unit of analysis was the study; any financial tie present for any study principal investigator resulted in the study being assessed as having a financial tie.

We searched five different sources for financial ties: the trial publication, Medline for other publications by the principal investigators, Google, ProPublica’s Dollars for Doctors, and the US Patent Office. We defined a financial tie as self reported if it was disclosed in the trial publication. We searched for additional financial ties in the other four sources outlined above. We report both self reported financial ties and the total financial ties (sum of the self reported financial ties and the financial ties identified via the additional search).

Our method for searching for additional financial ties was based on a previously described method that used Medline and Google.27 In Medline, we reviewed the first 10 publications of each principal investigator in which the principal investigator was either first or senior author. We limited the search for financial ties to the two years before the online publication date of the RCT. When we identified a financial tie, we confirmed the identity of the investigator of interest by matching his or her reported institutional affiliation with the one documented in the article. In Google, we combined the principal investigator’s name with the name of the drug manufacturer and reviewed the first five pages of Google search results.27

We expanded our search and also included ProPublica’s Dollars for Doctors and the US Patent Office. In both these sources, we searched the principal investigator’s first and last name and reviewed all results in the two years before the online publication of the paper. For each study, one of four abstractors (AA, RA, SS, AW) identified the financial ties of the study authors and abstracted all the characteristics of the study, and a second abstractor independently verified the presence of a financial tie and abstracted all characteristics. Any disagreement was reviewed by two clinician reviewers (SK and DK) and resolved by consensus.

Covariates

Our main covariate of interest was industry funding (dichotomized to any industry funding versus no industry funding) because several studies have found that industry funding is associated with positive study outcomes.7 28 29 30 31 32 We abstracted funding information from the information listed in the published trial and trial registries. We also collected data on multiple characteristics of studies that we thought may be related to the presence of financial ties, including RCT phase (phase III versus other), sample size (separated into four quarters), first author’s country of origin (US versus other; if there were multiple first authors, we used the first listed author’s country), specialty (cardiology versus oncology versus other), trial registration (registered versus unregistered), type of analysis (superiority versus non-inferiority), study design (active comparator versus placebo or nothing), outcome measure (clinical versus surrogate endpoint), and blinding (double blind versus other).

Statistical methods

We report the summary statistics to describe prevalence of self reported financial ties and total financial ties by trial characteristics and the frequency and type of compensation received by principal investigators. We examined differences by using a two sided, 0.05 level χ2 test of significance. Using established methods, we examined possible multicollinearity between industry funding and principal investigators’ self reported financial ties and total financial ties.33 34 35 36 37 Firstly, we built a logistic regression model of study outcomes data to get weights for predictors, using Fisher's scoring at each iteration (for 50 iterations). We also calculated the correlations among the parameter estimates and found no unusually large parameter estimates or standard errors (largest coefficient=1.05, SE=0.43) as sometimes seen in multicollinearity. Next, we calculated the condition indices and variance inflation factors by using the weight values from the final iteration of the logistic regression model above. We found no large condition indices (all <14) or variance inflation factors (all <2). The variance inflation factors for self reported financial ties (1.63), total financial ties (1.65), and industry funded studies (1.48 when self reported financial ties were included in the model; 1.54 when total financial ties were included in the model) were small, suggesting that collinearity was not a problem.

Using logistic regression, we examined the association between financial ties and study outcomes after adjustment for study funding. In a secondary analysis, we examined the association between financial ties and study outcomes after adjustment for additional RCT characteristics. We also tested for interactions and specifically examined whether the relation between financial ties and outcomes was modified by the source of funding. We also did a stratified analysis examining the relation between financial ties and study outcome with studies categorized by industry funding.

In a sensitivity analysis, we examined the effect of excluding papers in which the authors had no opportunity to declare financial ties on the relation between financial ties and study outcomes. Finally, as five papers reported data from two studies, we did a sensitivity analysis in which we retained only data from the first study reported to prevent double counting of financial ties. We used SAS statistical software, version 9, for statistical analysis.

Results

Characteristics of included RCTs

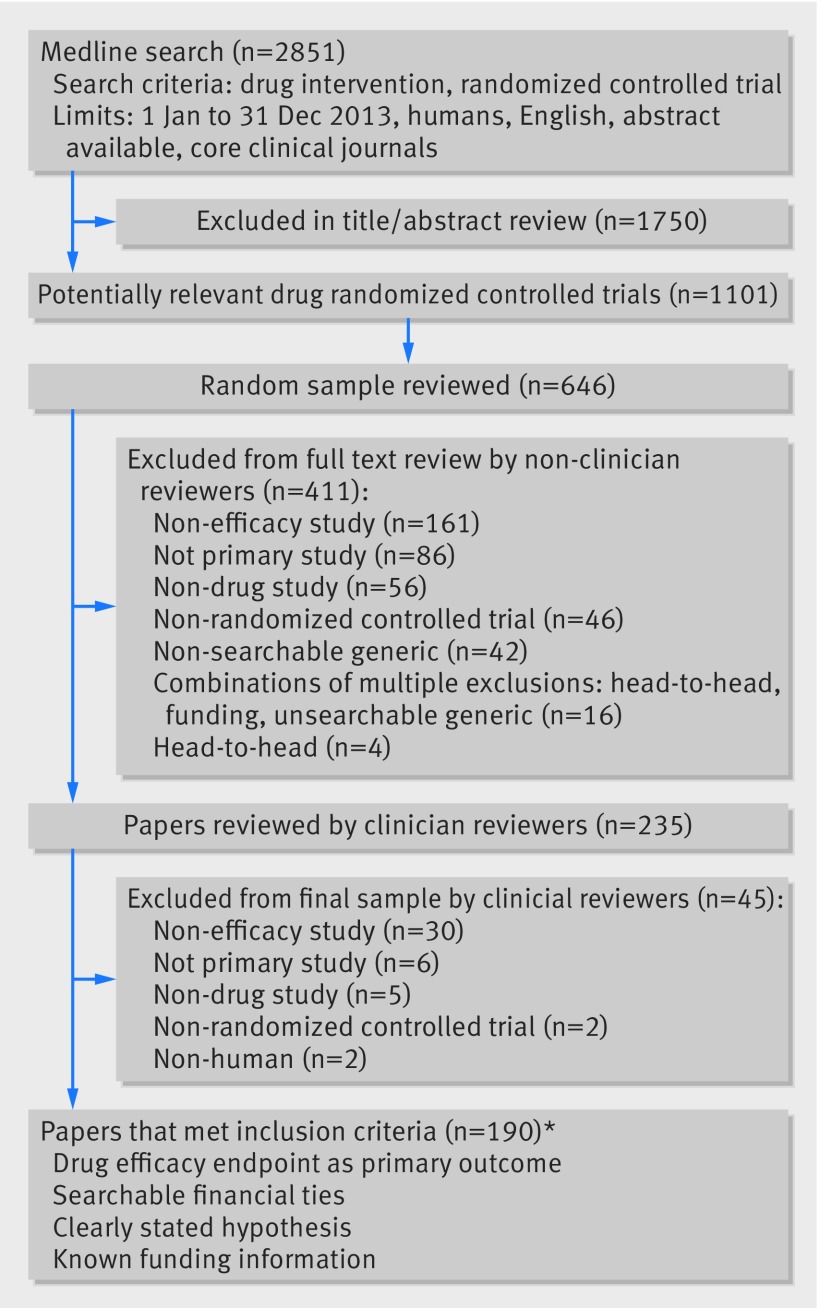

Among the total sample of 646 papers reviewed, 190 papers comprising 195 studies met inclusion criteria and were included in the final sample (fig 1). Among the 456 excluded papers, most did not meet inclusion criteria because of non-efficacy study design (n=191; 42%), non-primary data (n=92; 20%), or non-drug intervention (n=61; 13%). Included studies were primarily phase III (52%) and were funded by industry (69%). First authors were predominately based in the US (74/195; 38%). Best represented specialties included cardiology (16%), oncology (11%), infectious diseases (11%), urology (7%), and gastroenterology (6%). The vast majority of RCTs were registered in clinicaltrials.gov or another registry (94%), designed as superiority trials (89%), double blinded (75%), and placebo controlled (75%) (table 1).

Fig 1 Flowchart of articles in review. *190 papers, which included 195 distinct studies

Table 1.

Prevalence of total financial ties by characteristics of trials (n=195). Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| No | Financial ties* present | Financial ties* absent | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT phase | ||||

| Phase II | 50 | 38 (76) | 12 (24) | <0.001 |

| Phase III | 102 | 81 (79) | 21 (21) | |

| Phase IV | 17 | 8 (47) | 9 (53) | |

| Other | 26 | 5 (19) | 21 (81) | |

| RCT type | ||||

| Double blinded | 147 | 102 (69) | 45 (31) | 0.47 |

| Single blinded | 7 | 5 (71) | 2 (29) | |

| Open label | 39 | 23 (59) | 16 (41) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Sample size | ||||

| Quarter 1 (13-118) | 49 | 22 (45) | 27 (55) | <0.001 |

| Quarter 2 (119-315) | 49 | 33(67) | 16 (33) | |

| Quarter 3 (316-615) | 49 | 33 (67) | 16 (33) | |

| Quarter 4 (616-21 105) | 48 | 44 (92) | 4 (8) | |

| Specialty † | ||||

| Cardiology | 31 | 22 (71) | 9 (29) | 0.28 |

| Oncology | 22 | 18 (82) | 4 (18) | |

| Infectious disease | 22 | 14 (64) | 8 (36) | |

| Urology | 13 | 11 (85) | 2 (15) | |

| Gastroenterology | 12 | 9 (75) | 3 (25) | |

| Other | 95 | 58 (61) | 37 (39) | |

| Funding source | ||||

| Any industry funding | 134 | 113 (84) | 21 (16) | <0.001 |

| No industry funding | 61 | 19 (31) | 42 (69) | |

| Trial registration | ||||

| Yes | 183 | 129 (70) | 54 (30) | 0.001 |

| No | 12 | 3 (25) | 9 (75) | |

| Type of analysis | ||||

| Superiority | 174 | 112 (64) | 62 (36) | 0.004 |

| Non-inferiority | 21 | 20 (95) | 1 (5) | |

| Comparator | ||||

| Placebo | 146 | 94 (64) | 52 (36) | 0.09 |

| Active | 49 | 38 (78) | 11 (22) | |

| Outcome measure | ||||

| Surrogate | 65 | 42 (65) | 23 (35) | 0.52 |

| Clinical | 130 | 90 (69) | 40 (31) | |

| First and senior author affiliation by continent (n=397) ‡ | ||||

| North America | 191 | 137 (72) | 54 (28) | <0.001 |

| Europe | 137 | 80 (58) | 57 (42) | |

| Asia | 52 | 8 (15) | 44 (85) | |

| Other | 17 | 6 (35) | 11 (65) | |

| First and senior author affiliation by country, top 5 | ||||

| United States | 169 | 119 (70) | 50 (30) | <0.001 |

| United Kingdom | 31 | 22 (71) | 9 (29) | |

| Canada | 21 | 17 (81) | 4 (19) | |

| Germany | 21 | 14 (67) | 7 (33) | |

| France | 19 | 11 (58) | 8 (42) | |

| Other | 136 | 48 (35) | 88 (65) | |

RCT=randomized controlled trial.

*Total financial ties (both self reported and found by additional search).

†Top five most common specialties in sample.

‡Of 190 papers reporting 195 studies, seven studies had multiple first or senior authors and one had single author for total of 397 authors.

Prevalence of industry financial ties

Of the 195 studies, seven had multiple first or senior authors and one had a single author, making a total of 397 principal investigators. Among all principal investigators, 197 (50%) self reported financial ties at the time of publication, 186 (47%) self reported no financial ties, and 14 (4%) did not have an opportunity to do so (that is, the journal had no disclosure section) (table 2). Our online search found an additional 34 principal investigators with financial ties, all of whom had had an opportunity to disclose financial ties in the paper. Of these 34 principal investigators with additional ties found by search, 17 (50%) were US based authors. Overall, 231 (58%) principal investigators had financial ties. The prevalence of total financial ties (both self reported and identified by the additional search) was similar between first authors and senior authors (55.7% v 60.7%; P=0.31). Among all principal investigators, 156 (39%) had advisor/consultancy payments, 81 (20%) had speakers’ fees, 81 (20%) had unspecified financial ties, 52 (13%) had honorariums, 52 (13%) had employee relationships, 52 (13%) had travel fees, 41 (10%) had stock ownership, and 20 (5%) had a patent related to the publication (table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of financial ties in principal investigators of 195 studies*

| Total No (%) (n=397)† | Financial ties self reported | Additional financial ties identified by search | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of financial ties | |||

| Any financial ties | 231 (58) | 197 | 34 |

| No financial ties | 166 (42) | NA | NA |

| Type of financial ties ‡ | |||

| Consultant/advisor payments | 156 (39) | 104 | 21 |

| Speakers’ fees | 81 (20) | 43 | 10 |

| Type not specified | 81 (20) | 40 | 10 |

| Honorariums | 52 (13) | 16 | 5 |

| Employee relationship | 52 (13) | 43 | 2 |

| Travel fees | 52 (13) | 26 | 8 |

| Stock ownership | 41 (10) | 25 | 3 |

| Patent | 20 (5) | 13 | 1 |

NA=not applicable.

*Each study had one to four principal investigators.

†Includes 14 authors who had no opportunity to declare financial ties (no disclosure section in journal). These 14 principal investigators had no financial ties identified in search.

‡Principal investigators may have had more than one type of financial tie.

Study characteristics and prevalence of financial ties

Self reported financial ties were present in 117 (60%) of the 195 included studies, and total financial ties (self reported and additional financial ties identified in the search) were present in 132 (68%) of the 195 included studies (table 3). The overall prevalence of financial ties was 76% (103/136) among positive studies and 49% (29/59) among negative studies. Authors from the US were more likely to have financial ties than were authors from other countries (70% v 49%; P<0.001).

Table 3.

Association between financial ties and primary study outcome after adjustment for industry funding

| No (%) | Total No | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive study | Negative study | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Self reported financial ties | |||||

| Yes | 92 (79) | 25 (21) | 117 | 2.84 (1.5 to 5.3)* | 2.94 (1.4 to 6.1) |

| No | 48 (62) | 30 (38) | 78 | – | – |

| Industry funding | |||||

| Yes | 98 (73) | 36 (27) | 134 | 1.65 (0.87 to 3.1)† | 0.93 (0.43 to 2.0) |

| No | 38 (62) | 23 (38) | 61 | – | – |

| Total financial ties | |||||

| Yes | 103 (78) | 29 (22) | 132 | 3.23 (1.7 to 6.1)* | 3.57 (1.65 to 7.7) |

| No | 33 (52) | 30 (48) | 63 | – | – |

| Industry funding | |||||

| Yes | 98 (73) | 36 (27) | 134 | 1.65 (0.87 to 3.1)† | 0.83 (0.37 to 1.8) |

| No | 38 (62) | 23 (38) | 61 | – | – |

*Unadjusted association between financial ties and study outcome.

†Unadjusted association between industry funding and study outcome.

Prevalence of financial ties did not differ by specialty (P=0.28). Registered trials were more likely to have financial ties than were non-registered trials (70% v 25%; P=0.001). Financial ties were more prevalent in industry funded trials than in non-industry funded trials (84% v 31%; P<0.001). The prevalence of financial ties was lower in superiority trials than in non-inferiority trials (64% v 95%; P=0.004). We found no significant differences in the prevalence of financial ties between placebo controlled and active controlled trials or between trials with surrogate and clinical outcomes (table 1).

Financial ties and study outcome

In the unadjusted analysis, both self reported financial ties and total financial ties were associated with positive study outcomes (table 3). After adjustment for study funding, self reported financial ties (odds ratio 2.94, 95% confidence interval 1.4 to 6.1; P=0.004) and total financial ties (3.57, 1.7 to 7.7; P=0.001) were still associated with positive study outcomes (table 3).

The interaction between total financial ties and industry funding on study outcomes was not significant (P=0.15). In the stratified analysis, self reported financial ties were associated with positive study outcome for industry funded studies (3.36, 1.2 to 9.8; P=0.027) and for non-industry funded studies (2.53, 0.42 to 15; P=0.31) (table 4).

Table 4.

Association between financial ties and primary outcome stratified by funding source

| Industry funded (n=134) | Not industry funded (n=61) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | No (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Positive | Negative | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Positive | Negative | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||

| Self reported financial ties | |||||||||||

| Present | 81 (79) | 22 (21) | 3.03 (1.3 to 7.1) | 3.36 (1.2 to 9.8) | 11 (79) | 3 (21) | 2.72 (0.67 to 11) | 2.53 (0.42 to 15) | |||

| Absent | 17 (55) | 14 (45) | – | – | 27 (57) | 20 (43) | – | – | |||

| Total financial ties | |||||||||||

| Present | 89 (79) | 24 (21) | 4.94 (1.9 to 13) | 5.01 (1.52 to 17) | 14 (74) | 5 (26) | 2.10 (0.64 to 6.9) | 3.49 (0.62 to 20) | |||

| Absent | 9 (43) | 12 (57) | – | – | 24 (57) | 18 (43) | – | ||||

In the secondary analysis, we controlled for additional factors: RCT phase, RCT type, sample size, country of first author, specialty, trial registration, study design, type of analysis, comparator, primary outcome measure, and study blinding. These characteristics did not appreciably affect the relation between financial ties and study outcomes (total financial ties: odds ratio 3.37, 1.4 to 7.9; P=0.006) (table 5).

Table 5.

Association between financial ties and study outcomes after adjustment for characteristics of RCT (n=195)

| No | Self reported financial ties | Total financial ties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |||

| Financial ties * | ||||||

| Any | 132* | 2.84 (1.5 to 5.3) | 2.85 (1.2 to 6.6) | 3.23 (1.7 to 6.1) | 3.37 (1.4 to 7.9) | |

| None (reference) | 63 | – | – | – | – | |

| Funding source | ||||||

| Any industry funding | 134 | 1.65 (0.87 to 3.1) | 0.86 (0.37 to 2.0) | 1.65 (0.87 to 3.1) | 0.79 (0.34 to 1.9) | |

| No industry funding (reference) | 61 | – | – | – | – | |

| RCT phase | ||||||

| Phase III | 102 | 1.61 (0.87 to 3.0) | 1.18 (0.56 to 2.5) | 1.61 (0.87 to 3.0) | 1.15 (0.54 to 2.4) | |

| Other (reference) | 93 | – | – | – | – | |

| RCT type | ||||||

| Open label/single blind | 46 | 1.23 (0.59 to 2.5) | 1.08 (0.43 to 2.7) | 1.23 (0.59 to 2.5) | 1.13 (0.45 to 2.9) | |

| Double blind (reference) | 147 | – | – | – | – | |

| Sample size | ||||||

| Quarter 4 (616-21 105) | 48 | 2.10 (0.82 to 5.4) | 1.03 (0.32 to 3.3) | 2.10 (0.82 to 5.4) | 1.05 (0.32 to 3.4) | |

| Quarter 3 (316-615) | 49 | 0.84 (0.36 to 1.9) | 0.56 (0.21 to 1.5) | 0.84 (0.36 to 1.9) | 0.58 (0.22 to 1.5) | |

| Quarter 2 (119-315) | 49 | 1.00 (0.43 to 2.3) | 0.72 (0.28 to 1.9) | 1.00 (0.43 to 2.3) | 0.65 (0.25 to 1.7) | |

| Quarter 1 (13-118) (reference) | 49 | – | – | – | – | |

| First author affiliation | ||||||

| United States | 74 | 0.94 (0.50 to 1.76) | 0.81 (0.39 to 1.7) | 0.94 (0.50 to 1.76) | 0.81 (0.39 to 1.7) | |

| Other (reference) | 121 | – | – | – | – | |

| Specialty | ||||||

| Cardiology | 31 | 1.06 (0.45 to 2.5) | 0.65 (0.24 to 1.8) | 1.06 (0.45 to 2.5) | 0.63 (0.23 to 1.7) | |

| Oncology | 22 | 0.93 (0.35 to 2.4) | 0.78 (0.26 to 2.4) | 0.93 (0.35 to 2.4) | 0.73 (0.24 to 2.2) | |

| Other (reference) | 142 | – | – | – | – | |

| Trial registration | ||||||

| Yes | 183 | 2.45 (0.76 to 7.9) | 1.75 (0.47 to 6.5) | 2.45 (0.76 to 7.9) | 1.70 (0.45 to 6.4) | |

| No (reference) | 12 | – | – | – | – | |

| Type of analysis | ||||||

| Non-inferiority | 21 | 9.99 (1.3 to 76) | 5.34 (0.60 to 47) | 9.99 (1.31 to 76) | 5.55 (0.63 to 49) | |

| Superiority (reference) | 174 | – | – | – | – | |

| Comparator | ||||||

| Active | 49 | 1.97 (0.91 to 4.3) | 1.46 (0.56 to 3.8) | 1.97 (0.91 to 4.3) | 1.35 (0.53 to 3.5) | |

| Placebo (reference) | 146 | – | – | – | – | |

| Outcome measure | ||||||

| Clinical | 130 | 0.52 (0.26 to 1.0) | 0.42 (0.19 to 0.92) | 0.52 (0.26 to 1.0) | 0.43 (0.20 to 0.93) | |

| Surrogate (reference) | 65 | – | – | – | – | |

OR=odds ratio; RCT=randomized controlled trial.

*Total financial ties (117 self reported).

We also examined the effect of excluding papers in which the investigators had no opportunity to declare conflicts on the relation between financial ties and study outcome. The exclusion of these papers had no effect on our findings (total financial ties: odds ratio 3.44, 1.4 to 8.4). Finally, we examined the effect of including only the first study in the five papers that reported multiple study results. This analysis had no effect on our findings (total financial ties: odds ratio 3.07, 1.6 to 5.9). The appendix includes a list of all included studies, their outcomes, presence of financial ties, and presence of industry funding.

Discussion

We found that more than half of principal investigators of RCTs of drugs had financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry and that financial ties were independently associated with positive clinical trial results even after we accounted for industry funding. These findings may raise concerns about potential bias in the evidence base.

Possible explanations for findings

The high prevalence of financial ties observed for trial investigators is not surprising and is consistent with what has been reported in the literature.11 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 One would expect industry to seek out researchers who develop expertise in their field38; however, this does not explain why the presence of financial ties for principal investigators is associated with positive study outcomes.9 One explanation may be “publication bias.” Negative industry funded studies with financial ties may be less likely to be published. The National Institutes of Health (NIH)’s clinicaltrials.gov registry was intended to ensure the publication of all trial results, including both NIH and industry funded studies, within one year of completion. However, rates of publication of results remain low even for registered trials.4 39 Although lack of publication of select industry funded studies may be an important explanation for our findings, small single site RCTs conducted in academic settings may also be less likely to get published because of a lack of interest from medical journals. Publication bias is an important factor to consider while reflecting on our findings, but the distribution of financial ties among unpublished papers is unknown and the effect of publication bias on the observed association is unclear and speculative.4

Other possible explanations for our findings exist. Ties between investigators and industry may influence study results by multiple mechanisms, including study design and analytic approach.2 3 10 40 41 If our findings are related to such factors, the potential solutions are particularly challenging. Transparency alone is not enough to regulate the effect that financial ties have on the evidence base, and disclosure may compromise it further by affecting a principal investigator’s judgment through moral licensing, which is described as “the unconscious feeling that biased evidence is justifiable because the advisee has been warned.”42 Social experiments have shown that bias in evidence is increased when conflict of interest is disclosed.42 One bold option for the medical research community may be to adopt a stance taken in fields such as engineering, architecture, accounting, and law: to restrict people with potential conflicts from involving themselves in projects in which their impartiality could be potentially impaired.43 However, this solution may not be plausible given the extensive relationship between drug companies and academic investigators.44 45 Other, incremental steps are also worthy of consideration. In the past, bias related to analytic approach was tackled by a requirement for independent statistical analysis of major RCTs.46 47 Independent analysis has largely been abandoned in favor of the strategy of transparency, but perhaps the time has come to reconsider this tool to reduce bias in the analysis of RCTs. This approach might be especially effective for studies that are likely to have a major effect on clinical practice or financial implications for health systems.48 Another strategy to reduce bias at the analytic stage may be to require the publishing of datasets. ICMJE recently proposed that the publication of datasets should be implemented as a requirement for publication.49 This requirement is increasingly common in other fields of inquiry such as economics.50 51 Although independent analyses at the time of publication may not be feasible for journals from a resource perspective, the requirement to release the dataset to be reviewed later if necessary may discourage some forms of analytical bias. Finally, authors should be required to include and discuss any deviations from the original protocol. This may help to prevent changes in the specified outcome at the analytic stage.

Strengths and limitations of study

This study has several strengths. Previous studies examining the link between financial ties and study outcome have been limited to one specialty,17 18 19 20 21 drug type,22 23 or journal.24 25 Our study provides a comprehensive examination of the link between principal investigators’ financial ties and study outcomes after accounting for industry funding and represents a cross section of published RCTs. In addition, previous studies have not attempted to disentangle the effect of individual principal investigator’s financial ties and industry funding on RCT outcomes. These two variables, although related, are different. Funding is awarded to institutions and represents professional gain and not personal financial gain. In the unadjusted analyses, we found that financial ties were strongly associated with positive study outcome. In multivariate analyses, financial ties had a strong and consistent relation with study outcome even after adjustment for source of funding. Although we did not find evidence of multicollinearity in our statistical analysis, we further examined the relation between financial ties and RCT results in an analysis stratified by industry funding. Among studies with financial ties, the percentage of studies with financial ties was similar for both industry and non-industry funded studies (table 4). The point estimates for the odds ratios in the stratified analysis were both positive, which suggests that financial ties of non-industry funded researchers are also important to examine. However, this analysis was limited by a small sample size. Future studies with larger sample sizes that are powered to examine the relation between financial ties and study outcome in non-industry funded studies are an important direction for this research and could help to improve our understanding of the relation between principal investigators’ financial ties and study outcome.

Our study also has several important limitations that deserve comment. Our analysis is cross sectional and cannot be used to draw conclusions about causation. In addition, we did not assess the quality of clinical trials included in our sample; this was beyond the scope of our study. However, we did assess sample size, study design, analysis type, and outcome measure, which are related to study quality, and none influenced the relation between financial ties and outcomes. Therefore, we believe it to be unlikely that formal quality assessment would have changed our findings. Our findings may also over-represent the financial ties of US (compared with non-US) investigators, as we used two US based resources to identify financial ties: US Patent Office and ProPublica’s Dollars for Doctors. Although this may have led to an overestimation of financial ties of US based authors, we identified financial ties for only two additional principal investigators through these sources, diminishing the possibility that the emphasis on US sources in our search strategy affected our findings. In addition, our assessment of exposure was limited by necessity. We counted the financial ties to manufacturers because these were clear and measurable. Distributors and competitors change owing to mergers and acquisitions, and sources of information are variable. We relied on our conservative, but robust, approach of taking the clearly identifiable manufacturer. We extracted information on the financial ties of principal investigators, who we defined as first and last authors. The principal investigators of a publication are usually more closely identified with their publication and are more directly responsible for its content; we did an exhaustive search to identify their financial ties. However, our definition may have caused us to miss some financial ties of other study investigators, which in turn may have caused us to underestimate the association between financial ties and study outcomes. Finally, we did not consider research support as a financial tie because research support is awarded to institutions and not individual investigators. In this study, we focused on ties that were representative of personal financial gain. This may have underestimated financial ties but is unlikely to have affected our main finding.

Conclusions

Financial ties of principal investigators are prevalent and are independently associated with positive clinical trial results. Given the importance of industry and academic collaboration in advancing the development of new treatments, more thought needs to be given to the roles that investigators, policy makers, and journal editors can play in ensuring the credibility of the evidence base.

What is already known on this topic

Financial ties to industry are common among principal investigators of randomized clinical trials

Many studies have examined the relation between study funding source and trial outcomes

Very few studies have examined the relation between principal investigators’ financial ties and study outcomes after accounting for the effect of industry funding

What this study adds

This study is a cross section of all randomized controlled trials published in 2013, taking advantage of new disclosure sources

It shows an independent association between the presence of personal financial ties of principal investigators to industry and positive trial outcomes

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix

Contributors: SK had the idea for the study. SK, DK, RA, AW, AA, and SS created the study design. RA, AW, AA, and SS collected the data. SK and DK verified the data. EM, WJB, SK, RA, AW, AA, SS, and DK analyzed and interpreted the data. RA, AW, AA, SS, SK, DK, EM, and WJB wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version for submission. RA, AW, AA, and SS contributed equally to the work and are considered co-first authors. SK is the guarantor.

Funding: This project was not directly supported by any research funds. SK is funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 HL116522-01A1, RO1 HL114563-01A1) and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (1IP1HX001994). DK’s work on this paper was supported by a Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (award number P30 CA008748).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work, other than that described above; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Data sharing: Dataset available from corresponding author on request.

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1.Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, et al. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the Users’ Guides to patient care. JAMA 2000;284:1290-6. 10.1001/jama.284.10.1290 pmid:10979117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naci H, Ioannidis JP. How good is “evidence” from clinical studies of drug effects and why might such evidence fail in the prediction of the clinical utility of drugs?Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2015;55:169-89. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124614 pmid:25149917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lathyris DN, Patsopoulos NA, Salanti G, Ioannidis JP. Industry sponsorship and selection of comparators in randomized clinical trials. Eur J Clin Invest 2010;40:172-82. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02240.x pmid:20050879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourgeois FT, Murthy S, Mandl KD. Outcome reporting among drug trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:158-66. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00006 pmid:20679560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sismondo S. How pharmaceutical industry funding affects trial outcomes: causal structures and responses. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1909-14. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.010 pmid:18299169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinson BC, Anderson MS, de Vries R. Scientists behaving badly. Nature 2005;435:737-8. 10.1038/435737a pmid:15944677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundh A, Sismondo S, Lexchin J, Busuioc OA, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:MR000033.pmid:23235689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang AT, McCoy CP, Murad MH, Montori VM. Association between industry affiliation and position on cardiovascular risk with rosiglitazone: cross sectional systematic review. BMJ 2010;340:c1344 10.1136/bmj.c1344 pmid:20299696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhry K, Love A. Key Opinion Leaders Interactions with Pharma. 2005. http://www.pharmexec.com/key-opinion-leaders-interactions-pharma.

- 10.Lexchin J. Those who have the gold make the evidence: how the pharmaceutical industry biases the outcomes of clinical trials of medications. Sci Eng Ethics 2012;18:247-61. 10.1007/s11948-011-9265-3 pmid:21327723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA 2003;289:454-65. 10.1001/jama.289.4.454 pmid:12533125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matheson A. How industry uses the ICMJE guidelines to manipulate authorship--and how they should be revised. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001072 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001072 pmid:21857808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamatakis E, Weiler R, Ioannidis JP. Undue industry influences that distort healthcare research, strategy, expenditure and practice: a review. Eur J Clin Invest 2013;43:469-75. 10.1111/eci.12074 pmid:23521369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Journals following the ICMJE recommendations. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors website. 2016. http://www.icmje.org/journals-following-the-icmje-recommendations/.

- 15.De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, et al. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:477-8. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-6-200409210-00109 pmid:15355883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viergever RF, Karam G, Reis A, Ghersi D. The quality of registration of clinical trials: still a problem. PLoS One 2014;9:e84727 10.1371/journal.pone.0084727 pmid:24427293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aneja A, Esquitin R, Shah K, et al. Authors’ self-declared financial conflicts of interest do not impact the results of major cardiovascular trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1137-43. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.056 pmid:23395075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bariani GM, de Celis Ferrari AC, Hoff PM, Krzyzanowska MK, Riechelmann RP. Self-reported conflicts of interest of authors, trial sponsorship, and the interpretation of editorials and related phase III trials in oncology. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2289-95. 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6706 pmid:23630201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amiri AR, Kanesalingam K, Cro S, Casey AT. Does source of funding and conflict of interest influence the outcome and quality of spinal research?Spine J 2014;14:308-14. 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.10.047 pmid:24231776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perlis RH, Perlis CS, Wu Y, Hwang C, Joseph M, Nierenberg AA. Industry sponsorship and financial conflict of interest in the reporting of clinical trials in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1957-60. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1957 pmid:16199844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perlis CS, Harwood M, Perlis RH. Extent and impact of industry sponsorship conflicts of interest in dermatology research. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52:967-71. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.020 pmid:15928613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pang WK, Yeter KC, Torralba KD, Spencer HJ, Khan NA. Financial conflicts of interest and their association with outcome and quality of fibromyalgia drug therapy randomized controlled trials. Int J Rheum Dis 2015;18:606-15. 10.1111/1756-185X.12607 pmid:26012523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riechelmann RP, Wang L, O’Carroll A, Krzyzanowska MK. Disclosure of conflicts of interest by authors of clinical trials and editorials in oncology. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4642-7. 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2482 pmid:17925561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman LS, Richter ED. Relationship between conflicts of interest and research results. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:51-6. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30617.x pmid:14748860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kjaergard LL, Als-Nielsen B. Association between competing interests and authors’ conclusions: epidemiological study of randomised clinical trials published in the BMJ. BMJ 2002;325:249 10.1136/bmj.325.7358.249 pmid:12153921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Opal SM, Laterre PF, Francois B, et al. ACCESS Study Group. Effect of eritoran, an antagonist of MD2-TLR4, on mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the ACCESS randomized trial. JAMA 2013;309:1154-62. 10.1001/jama.2013.2194 pmid:23512062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuman J, Korenstein D, Ross JS, Keyhani S. Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among panel members producing clinical practice guidelines in Canada and United States: cross sectional study. BMJ 2011;343:d5621 10.1136/bmj.d5621 pmid:21990257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ 2003;326:1167-70. 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167 pmid:12775614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ridker PM, Torres J. Reported outcomes in major cardiovascular clinical trials funded by for-profit and not-for-profit organizations: 2000-2005. JAMA 2006;295:2270-4. 10.1001/jama.295.19.2270 pmid:16705108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yaphe J, Edman R, Knishkowy B, Herman J. The association between funding by commercial interests and study outcome in randomized controlled drug trials. Fam Pract 2001;18:565-8. 10.1093/fampra/18.6.565 pmid:11739337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhandari M, Busse JW, Jackowski D, et al. Association between industry funding and statistically significant pro-industry findings in medical and surgical randomized trials. CMAJ 2004;170:477-80.pmid:14970094. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah RV, Albert TJ, Bruegel-Sanchez V, Vaccaro AR, Hilibrand AS, Grauer JN. Industry support and correlation to study outcome for papers published in Spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1099-104, discussion 1105. 10.1097/01.brs.0000161004.15308.b4 pmid:15864166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belsley D, Kuh E, Welsch R. Regression diagnostics: identifying influential data and sources of collinearity.John Wiley & Sons, 1980 10.1002/0471725153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haque A, Jawad A, Shabbout M, Cnaan A. Detecting multicollinearity in logistic regression models: an extension of BKW diagnostic. Proceeding of the 2002 Joint Statistical Meeting, American Statistical Association, Statistical Computing Section. American Statistical Association, 2002 [CD-ROM]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.LeSaffre E, Marx BD. Collinearity in generalized linear regression. Commun Stat Theory Methods 1993;22:1933-52 10.1080/03610929308831126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller K, Fetterman B. Regression and ANOVA: an integrated approach using SAS® Software.SAS Institute and John Wiley & Sons, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segerstedt B, Nyquist H. On the conditioning problem in generalized linear models. J Appl Stat 1992;19:513-26 10.1080/02664769200000047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perkmann M, Tartari V, McKelvey M, et al. Academic engagement and commercialization: A review of the literature on university-industry relations. Res Policy 2013;42:423-42 10.1016/j.respol.2012.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson ML, Chiswell K, Peterson ED, Tasneem A, Topping J, Califf RM. Compliance with results reporting at ClinicalTrials.gov. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1031-9. 10.1056/NEJMsa1409364 pmid:25760355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, et al. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS One 2008;3:e3081 10.1371/journal.pone.0003081 pmid:18769481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodenheimer T. Uneasy alliance--clinical investigators and the pharmaceutical industry. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1539-44. 10.1056/NEJM200005183422024 pmid:10816196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loewenstein G, Sah S, Cain DM. The unintended consequences of conflict of interest disclosure. JAMA 2012;307:669-70. 10.1001/jama.2012.154 pmid:22337676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis M, Johnston J. Appendix C: Conflict of interest in four professions: a comparative analysis. In: Lo B, Field MJ, eds. Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice.National Academies Press, 2009: 302-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tereskerz PM, Hamric AB, Guterbock TM, Moreno JD. Prevalence of industry support and its relationship to research integrity. Account Res 2009;16:78-105. 10.1080/08989620902854945 pmid:19353387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher JA, Kalbaugh CA. United States private-sector physicians and pharmaceutical contract research: a qualitative study. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001271 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001271 pmid:22911055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fontanarosa PB, Flanagin A, DeAngelis CD. Reporting conflicts of interest, financial aspects of research, and role of sponsors in funded studies. JAMA 2005;294:110-1. 10.1001/jama.294.1.110 pmid:15998899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauchner H. Editorial policies for clinical trials and the continued changes in medical journalism. JAMA 2013;310:149-50. 10.1001/jama.2013.8083 pmid:23787577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Psaty BM, Kronmal RA. Reporting mortality findings in trials of rofecoxib for Alzheimer disease or cognitive impairment: a case study based on documents from rofecoxib litigation. JAMA 2008;299:1813-7. 10.1001/jama.299.15.1813 pmid:18413875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taichman DB, Backus J, Baethge C, et al. Sharing Clinical Trial Data: A Proposal From the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:505-6. 10.7326/M15-2928 pmid:26792258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang AC, Li P. Is economics research replicable? Sixty published papers from thirteen journals say “usually not”. Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2015-083. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2015.

- 51.Warren E. Strengthening Research through Data Sharing. N Engl J Med 2016;375:401-3. 10.1056/NEJMp1607282 pmid:27518656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix