Abstract

Cp40 is a 14-amino acid cyclic analog of the peptidic complement inhibitor compstatin that binds with sub-nanomolar affinity to complement component C3 and has already shown promise in various models of complement-related diseases. The preclinical and clinical development of this compound requires a robust, accurate, and sensitive method for quantitatively monitoring Cp40 in biological samples. In this study, we describe the development and validation of an ultra-high performance liquid chromatography electrospray mass spectrometry method for the quantitation of Cp40 in human and non-human primate (NHP) plasma. Isotope-labeled Cp40 was used as an internal standard, allowing for the accurate and absolute quantitation of Cp40. Labeled and non-labeled Cp40 were extracted from plasma using reversed phase-solid phase extraction, with recovery rates exceeding 80%, indicating minor matrix effects. The triply charged states of Cp40 and isotope-labeled Cp40 were detected at m/z 596.60 and 600.34, respectively, via a Q-TOF mass spectrometer and were used for quantitation. The method was linear in the range of 0.18–3.58 μg/mL (r2≥0.99), with precision values below 1.75% in NHP and 1.79% in human plasma. The accuracy of the method ranged from −2.17% to 17.99% in NHP and from −0.26% to 15.75% in human plasma. The method was successfully applied to the quantitation of Cp40 in cynomolgus monkey plasma after an initial intravenous bolus of 2 mg/kg followed by repetitive subcutaneous administration at 1 mg/kg. The high reproducibility, accuracy, and robustness of the method developed here render it suitable for drug monitoring of Cp40, and potentially other compstatin analogs, in both human and NHP plasma samples during pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies.

Keywords: compstatin, absolute quantitation, UPLC-ESI-MS, method validation, plasma

1. Introduction

The complement system, as a central component of innate immunity and host defense, needs to be tightly controlled to avoid an attack on self-cells. Complement dysregulation has been shown to trigger various immune and inflammatory diseases, thereby establishing complement inhibition as a promising therapeutic strategy [1–3]. Cp40 is a cyclic 14-amino acid peptide (Fig. 1) that has shown promise as a therapeutic approach for the treatment of complement-mediated diseases [4]. As a member of the compstatin family of complement inhibitors, Cp40 prevents the activation of the central complement component C3, thereby impairing generation of pro-inflammatory effectors [5]. Cp40 selectively binds to human and non-human primate (NHP) forms of C3 and its active fragment C3b with subnanomolar affinity (KD = 0.5 nM) [4]. Currently, a Cp40-based drug candidate (AMY-101) is being clinically developed by Amyndas Pharmaceuticals for various indications ranging from paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) to transplantation [3,6].

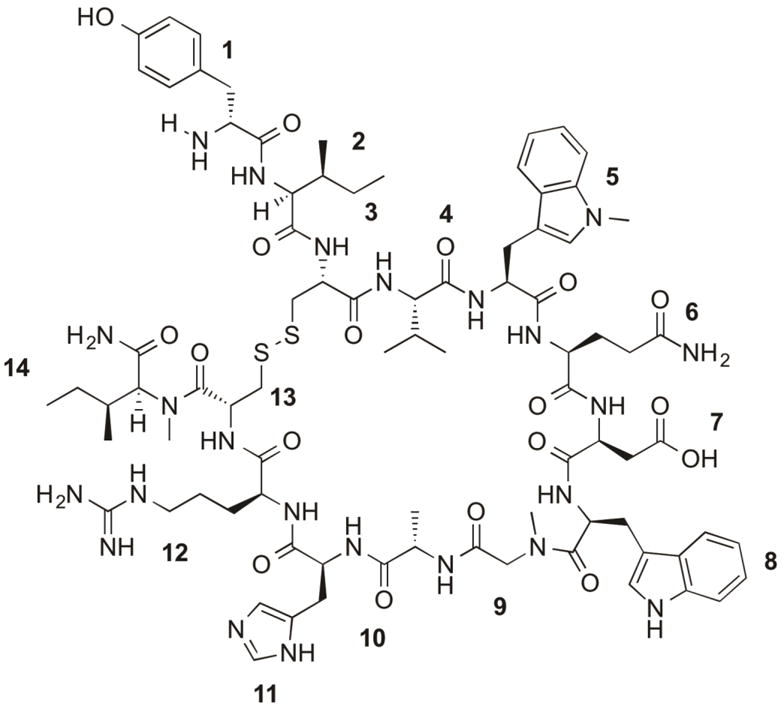

Fig. 1.

Structure and peptide sequence of Cp40 (H-DTyr1-Ile2-[Cys3-Val4-Trp(Me)5-Gln6-Asp7-Trp8-Sar9-Ala10-His11-Arg12-Cys13]-mIle14-NH2). The compstatin analog Cp40 is a cyclic 14-amino acid peptide with a disulfide bond formed between Cys3 and Cys13.

In a preclinical model of PNH, the peptidic inhibitor demonstrated dose-dependent inhibition of intravascular hemolysis in vitro and prevented C3 fragment deposition on PNH erythrocytes, which were used as a surrogate marker for C3-mediated extravascular hemolysis, suggesting a therapeutic benefit for Cp40 [7,8]. Cp40 also prevented impaired erroneous complement activation in serum samples from patients suffering from C3 glomerulopathy (C3G), a rare but life-threatening disorder for which there is no specific treatment [9]. Furthermore, in an NHP model of hemodialysis, significant filter-induced activation of C3 was observed during the dialysis session, which may contribute to inflammatory and coagulative complications. This filter-mediated complement activation was successfully abrogated by a single bolus injection of Cp40, and increased levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 were observed in the Cp40-treated animals [10]. Finally, Cp40 has shown efficacy in NHP models of induced and naturally occurring periodontitis, during which local treatment with the inhibitor significantly reduced markers of inflammation and bone loss [11–13].

Further preclinical and clinical development of Cp40 requires detailed knowledge about the pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties of this inhibitor. Previous studies suggested a distinct PK profile of Cp40 when compared to typical peptide drugs, with low terminal plasma elimination of Cp40 after intravenous injection in NHPs [4]. It was hypothesized that the high abundance of the target protein C3 in plasma (~1 mg/mL) and the tight binding of Cp40 to this protein result in a target-driven elimination profile [4]. Subcutaneous administration of the peptide showed high bioavailability and a sustained plasma concentration profile, with the drug remaining in excess of the plasma C3 level for an extended period [8]. Despite the progress that has been made in characterizing the in vivo properties of Cp40 in various models, more information is needed to guide the development of a suitable therapeutic regimen. The associated evaluation of PK/PD profiles relies critically on a robust and accurate method for the determination of Cp40 concentrations in NHP and human plasma.

In the present study, we have developed and validated an analytical workflow based on careful sample preparation, reproducible compound extraction, and highly sensitive quantitation, using high-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) to monitor Cp40 levels in human and NHP plasma samples. The method is based on LC-MS using isotope-labeled Cp40 as an internal standard (IS), which allows for the absolute quantitation of Cp40 in plasma [14,15]. We then applied the optimized method to study the PK properties of Cp40 in cynomolgus monkeys after subcutaneous administration.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Compounds and reagents

The compstatin analog Cp40 (H-DTyr-Ile-[Cys-Val-Trp(Me)-Gln-Asp-Trp-Sar-Ala-His-Arg-Cys]-mIle-NH2) was prepared by solid-phase peptide synthesis, purified as an acetate salt using reversed-phase HPLC, and lyophilized as described previously [4]. Isotope-labeled Cp40 containing a 13C/15N-Arg residue at position 12 (Fig. 1) was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA) and used as an IS. The identity and purity of both peptides were verified by UPLC-MS (Waters). The purity of Cp40 was 97.1%, and the purity of the isotope-labeled analogue was determined as being higher than 96%. Ultrapure water (MilliQ; Millipore) was used in all experiments. Acetonitrile was purchased from Fischer Scientific (HPLC grade), and formic acid from Thermo Scientific (LC-MS grade).

2.2 Biological samples

Human peripheral blood was collected from healthy volunteers in standard EDTA and serum Vacutainer tubes (BD Pharmingen, Milan, Italy) after venipuncture according to standard procedures, following informed consent as approved by the local Institutional Review Board. Blood samples were centrifuged at ~800 × g for 10 min to obtain plasma and were immediately frozen until further analysis. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

NHP blood samples were collected from cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) in standard EDTA and serum Vacutainer tubes (BD Pharmingen, Milan, Italy), centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 min to obtain plasma, and immediately frozen and shipped to the University of Pennsylvania for further analysis. All NHP studies were performed in accordance with animal welfare laws and regulations, as approved and enforced by the IACUC of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited SICONBREC facility (Makati, Philippines).

2.3 Liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis

Chromatographic analysis was performed using an Acquity UPLC system (Waters, Milford MA) with a temperature-controlled autosampler. An Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (130 Å, 1.7 μm, 1 mm × 100 mm; Waters) equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 VanGuard pre-column cartridge (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 5 mm; Waters) was used for the separation of the analytes. The autosampler was kept at 4°C and the column temperature at 40°C. The injection volume was 5 μL. The mobile phase consisted of water (A) and acetonitrile (B), both containing 0.1% formic acid. The following gradient was applied: 0–2 min 3% B, 2.5 min 15% B, 7 min 55% B, 8–10 min 95% B, 10.3–16 min 3% B at a flow rate of 0.15 mL/min. Under these conditions, Cp40 and the IS co-eluted at 4.8 ± 0.2 min.

A SYNAPT G2-S QTOF mass spectrometer (Waters) was operated in the positive ion mode using an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. ESI parameters were as follows: capillary voltage 2 kV, cone voltage 40 V, source temperature 120°C, desolvation temperature 350°C, desolvation gas (600 L/h). The spectra were acquired at the ‘sensitivity’ acquisition mode of the instrument with ESI positive polarity settings and the peptides being quantified on MS1 level. The m/z range was 100–1800 and the scan time was set at 0.5 sec. Data acquisition and analysis, were performed using MassLynx v4.1 (Waters, Milford, MA) with a mass window of ± 0.3. Using these acquisition settings, the average number of data points per chromatographic peak was 16.

2.4 Sample preparation and extraction

2.4.1 Preparation of standard solutions and plasma samples

Stock solutions of Cp40 and IS were prepared in ultrapure water (MilliQ) at 1 mg/mL. Concentrations of stock solutions were determined by measuring the absorption at 280 nm using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Wilmington, DE) and an extinction coefficient of 12615. Working solutions were prepared by diluting stock solutions 10-fold in 2.2% phosphoric acid (220 mmol/L), which was found to yield the highest recovery rate of the peptide in plasma (concentrations were tested in the range of 1–4%). All solutions were freshly prepared. Standard solutions were transferred in high-recovery polypropylene vials (LoBind, Eppendorf) prior to analysis.

Quality control (QC) samples were prepared by spiking naïve human or NHP plasma (30 μL) with the peptide at concentrations representing the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ), low QC, middle QC, and high QC (0.18, 0.29, 1.79, and 4.5 μg/mL, respectively). LLOQ was defined as the lowest concentration of Cp40 quantified with an acceptable precision and accuracy. Precision RSD values for the LLOQ samples were 0.32 and 0.39%, and accuracy values were defined at 17.99 and 11.79% in human and monkey plasma, respectively. These values are within the acceptable limits according to the FDA specifications (relative absolute deviation less than 20%) [16]. Calibration standard curves were prepared in 30 μL of plasma (naïve human or NHP) at concentrations of 0.18, 0.36, 0.72, 1.79, and 3.58 μg/mL. Unknown plasma samples (30 μL) from NHP injected with Cp40 were thawed on ice. All samples described above were spiked with a constant concentration of IS (0.36 μg/mL) and diluted 10-fold in 2.2% phosphoric acid to a final volume of 200 μL.

2.4.2 Extraction of peptides from plasma samples

Cp40 and IS were extracted from plasma samples using solid-phase extraction (SPE) in a 96-well plate format (HLB Oasis μElution plates, 30 μm, 10 mg; Waters). The SPE material was conditioned using methanol, acetonitrile, and water (0.5 mL each). Samples were loaded onto the cartridges under vacuum; cartridges were washed with 0.5 mL of 20% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid). Due to the nonpolar character of most amino acids in Cp40, the SPE column could be washed with a solution of 20% acetonitrile without eluting the peptides. For one-step peptide elution from the SPE column, a 80% acetonitrile solution (2 × 100 μL) was used. Of note, under UPLC conditions Cp40 was eluted at 4.82 min (i.e., ~36% acetonitrile, 0.1%FA). Initially, samples were allowed to elute under gravity in a LoBind plate (Acquity UPLC 700-μL round 96-well sample plate, Waters) for 15 min using 80% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid). Vacuum was then applied to the plate to collect the remaining elution solvent. The eluted solutions were diluted 10-fold in 10% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) and transferred to vials (polypropylene plastic, screw-top vial, 300 μL, Waters) for LC-MS analysis. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate by UPLC-MS using the parameters described in paragraph 2.3.

2.5 Method validation

The analytical method was validated using human and NHP plasma samples, including evaluation of selectivity, linearity, precision and accuracy, recovery, and stability. Isotope-labeled Cp40 was used as the IS for accurate and absolute quantitation throughout the study.

2.6 Selectivity

Selectivity was evaluated for blank and spiked samples from both human and cynomolgus monkey plasma samples. Plasma was spiked with Cp40 at the LLOQ levels to validate the absence of substances of the biological matrix that would interfere with the retention time of the analyte or the IS.

2.7 Linearity

The linearity of the method was evaluated in calibration-standard samples at Cp40 concentrations ranging from 0.18 to 3.58 μg/mL in triplicate samples run on three consecutive days, using isotope-labeled Cp40 as the IS. Standard curves were calculated using a weighted least squares linear regression between the peak area ratios of Cp40 to the IS and the theoretical Cp40 concentrations in the calibration standards.

2.8 Precision and accuracy

The intra-day precision and accuracy of the method were determined by analysis of four QC samples in four replicates (n=4) at concentrations of 0.18 μg/mL (LLOQ), 0.29 μg/mL (low), 1.79 μg/mL (medium), and 4.5 μg/mL (high) on a single run. Inter-day precision and accuracy were determined by the analysis of the QC samples described above (n=4) on three different days. Precision was expressed as percentage of the relative standard deviation (RSD); accuracy was expressed as a function of the deviation from theoretical values and calculated as: [(mean calculated concentration – nominal concentration)/(nominal concentration)] × 100. Precision values (% RSD) were not to exceed 15% of the RSD, except for the LLOQ, which was not to exceed 20%. Mean values for accuracy were to be within 15% of the nominal value, except for the LLOQ, which was not to deviate by more than 20% [16].

2.9 Extraction Recovery

Extraction recoveries of Cp40 and the IS were evaluated in human and NHP plasma at three different concentrations (0.18, 0.36, and 3.6 μg/mL) for Cp40 and a single concentration (0.36 μg/mL) for the IS. Extractions were performed in three replicates (n=3) for the NHP plasma and in two replicates (n=2) for the human plasma. Four analytical replicates (n=4) were performed for each one of the extracted samples. Recovery was calculated as the ratio of the mean peak areas obtained from blank plasma samples spiked with Cp40 and IS before SPE extraction and the mean peak areas from blank plasma samples spiked directly after SPE extraction with equivalent concentrations of Cp40 and IS. Recoveries at levels above LOQ (0.18 μg/mL) were in a range of 80–91% for NHP plasma and 87–100% for human plasma.

2.10 Stability

The stability of the standard samples was investigated in human and NHP plasma following SPE, employing three QC samples at 0.18, 0.36, and 3.58 μg/mL and exposed for different time periods under different temperature conditions. QC samples were prepared in triplicate and kept at room temperature (to determine bench-top stability) and at 4°C (autosampler conditions) for up to 48 h.

2.11 Application of the method for the quantitative determination of Cp40 in NHP plasma

A repetitive subcutaneous dose study of the compound was performed at the Simian Conservation and Breeding Research Center (SICONBREC; Makati City, Philippines) in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Cp40 was dissolved in water for injection, supplemented with dextrose (5%) to achieve an isotonic solution. Two hours prior to the initiation of subcutaneous administration, two healthy animals (1 male, 1 female) were each given a single intravenous bolus injection of 2 mg/kg Cp40. Subsequently, 13 and 11 subcutaneous injections at doses of 1 mg/kg each were administered to the male and female animals, respectively, at 12-h intervals, resulting in a total treatment period of 144 hours for the male and 120 hours for the female. To assess Cp40 elimination kinetics, blood samples were collected prior to the bolus and the first subcutaneous injection as well as 0.5, 4, 8, and 12 h after individual injections during the treatment and 72 h after the last administration.

2.12 Determination of C3 levels in plasma

Total levels of complement component C3 in plasma were determined by immunonephelometry using the N Antisera to Human Complement Factors (C3c) assay kit (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany). The assay was validated for the quantitation of C3 in plasma of cynomolgus monkeys after determining the correlation between C3 concentrations measured in human and monkey plasma to account for differential reactivity of the antibodies in the kit; for this purpose, serial dilutions of monkey plasma were spiked with known concentrations of purified C3 from cynomolgus monkey. Based on this correlation analysis, a correction factor (CF) of 1.2 was determined. The following equation was used to calculate the final concentration of C3 in NHP plasma: [C3] = [C3*] × CF, where [C3*] are the values measured by nephelometry. The assay was used to monitor C3 baseline levels as well as C3 levels during the course of the treatment.

3. Results & Discussion

3.1 Development of the analytical method and mass spectrometry

The main purpose of developing and validating the present method was to accurately quantify plasma levels of the complement inhibitor Cp40, for elucidating both the non-typical PK profile of the compound and for monitoring drug levels during preclinical development in NHP disease models and potential clinical studies. Owing to the demands concerning sensitivity and robustness, we employed a combination of SPE and UPLC-ESI-MS to extract Cp40 from plasma samples and determine its concentration. Isotope-labeled Cp40 was employed as the IS throughout the analyses. The isotope-labeled peptide has the same physico-chemical properties as the non-labeled analog and was therefore expected to show equivalent behavior during sample preparation, storage, extraction, and chromatography [14]. The distinct molecular mass and isotopic signature of the IS enabled absolute quantitation by MS and allowed for an adjustment of the variability in MS signal intensities caused, for example, by matrix effects or losses during the extraction step when the IS is spiked at constant concentrations [17].

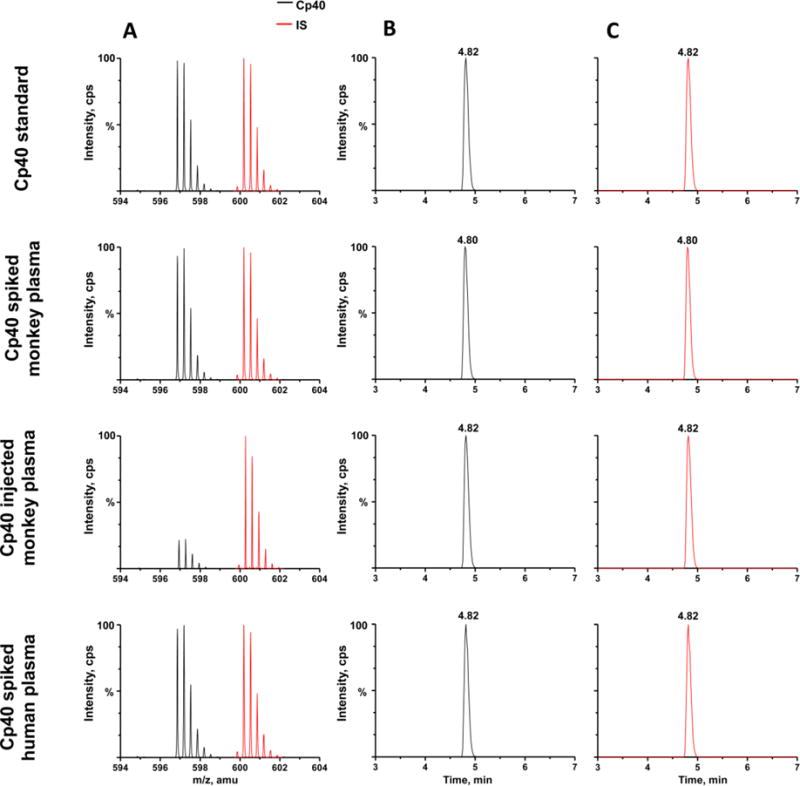

The Q-TOF MS was operated in the positive ion mode, and ion intensities of Cp40 and the IS were recorded in the range of m/z 200–1400. ESI conditions were optimized to yield maximum ion responses for both compounds. Absolute quantitation occurred using the triply charged states of Cp40 and the IS, detected at m/z 596.60 and 600.34, respectively, in both NHP and human plasma samples (Fig. 2A). The triply charged precursor molecules provided lower limits of quantitation and improved precision when compared to the doubly charged precursor molecules.

Fig. 2.

Cp40 and the internal standard (IS) were spiked into blank injection buffer (10% ACN) as a standard, as well as into naïve NHP and human plasma at a concentration of 0.29 μg/mL. Cp40 was injected intravenously into cynomolgus monkeys at 2 mg/kg, followed by repeated subcutaneous injections of 1 mg/kg each. Mass spectra and chromatograms of Cp40 and the IS from the samples above are shown in the figure. A. Spectra of Cp40 (black, m/z 596.891) and the IS (red, m/z 600.225) as triply charged molecules. B,C. Extracted ion chromatograms of Cp40 (black, m/z 596.891) and the IS (red, m/z 600.225), respectively.

Chromatographic conditions were tested and evaluated in order to improve the peak resolution and decrease the Cp40 retention time. An Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column was employed, and optimal chromatography conditions were achieved using acetonitrile and water, with 0.1% formic acid as the mobile phase and the gradient profile described in Section 2.3. As expected, no difference was observed between the retention times of Cp40 and the IS, and high peak resolution was achieved for both analytes (Fig. 2B, 2C).

3.2 Method validation

3.2.1 Selectivity

The selectivity of an analytical method refers to the extent that other substances interfere with the detection of the analyte [18]. Total drug plasma levels from human and NHP were tested in order to detect any endogenous components that could interfere with the analysis. The selectivity of the method was investigated by comparing naïve human and NHP plasma samples with those of plasma samples spiked with Cp40 and the IS at the LLOQ concentration. We also compared naïve NHP plasma with plasma samples of cynomolgus monkeys after administration of Cp40. Under all conditions, Cp40 and isotope-labeled Cp40 co-eluted with a retention time of 4.82 min, and no other mass peaks were detected at this retention time, confirming that there is no significant interference by endogenous molecules in human or NHP plasma with the UPLC-ESI-MS analysis of Cp40.

3.2.2 Linearity

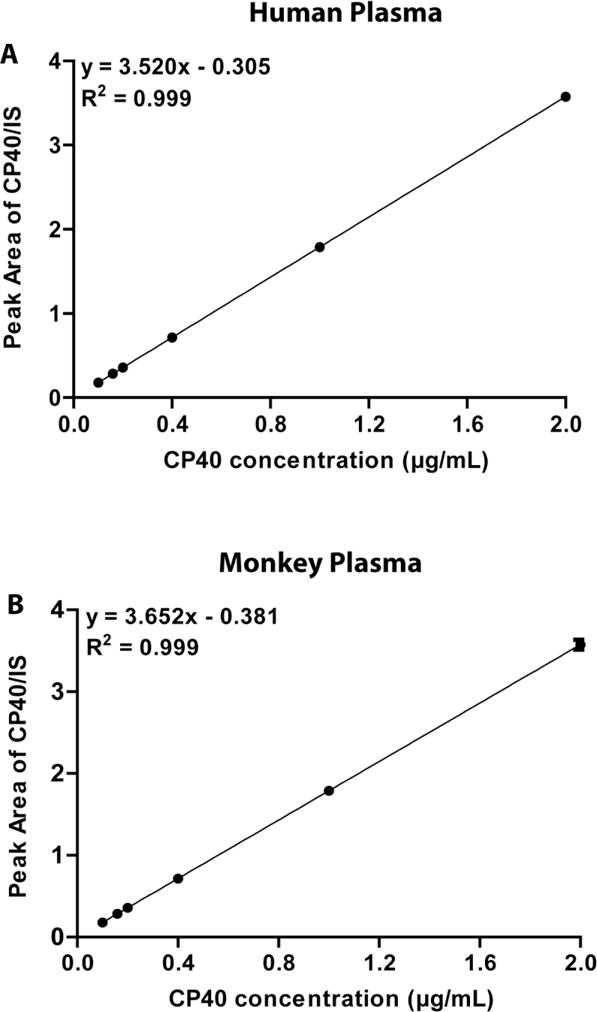

The assay was linear for Cp40 concentrations ranging from 0.18 to 3.58 μg/mL in both human and NHP plasma, with mean values of the regression equations for Cp40 of y = 3.520× – 0.305 (r2 = 0.999) and y = 3.652× – 0.381 (r2 = 0.999), respectively (Fig. 3). The LLOQ for the determination of Cp40 was at 0.18 μg/mL, which is sensitive enough to allow for the quantitation of Cp40 in complete pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies in human and NHP plasma samples covering a large range of concentrations. At this LLOQ level, the precision and accuracy values were below 20%, which are within the acceptable limits according to the FDA specifications [16].

Fig. 3.

Standard curves of Cp40 in human (A) and NHP (B) naïve plasma. The x-axis displays the spiked Cp40 concentration in plasma, and the y-axis corresponds to the ratio of the Cp40 peak area (counts) divided by the respective IS peak area (counts).

3.2.3 Precision and accuracy

According to IUPAC, the precision of a method refers to the variability observed between independent quantitative measurements under defined conditions, and accuracy refers to the consistency of the result of a measurement and the true value of measurement [18]. We evaluated the precision and accuracy of our developed method within the same day of analyses (intra-day) and when repeated over a course of 3 days (inter-day) for a series of QC samples (Table 1). The intra-and inter-day precision for the analysis of NHP samples ranged from 0.16 to 1.75 (% RSD), respectively. The assay was accurate for all tested QC standards within the FDA-required accuracy limits, and the values varied from 17.99 to −2.17%, with the LLOQ sample showing the lowest accuracy within the series. The corresponding intra- and inter- day precision values for human plasma ranged from 0.08 to 1.78 (% RSD), respectively. Similarly, the assay was accurate within the FDA-required accuracy limits for all tested concentrations, and values varied from 11.79 % (LLOQ standard) to −1.96 % RSD. The data demonstrate that the precision and the accuracy of the method are within the FDA acceptance criteria, which should not exceed 15% of the RSD [16].

Table 1.

Intra- and inter-day precision and accuracy of the assay for three QC standards spiked into NHP and human plasma samples.

| Plasma | Concentration (μg/mL) | Measured Concentration (μg/mL, mean ± S.D.) | Precision (RSD) | Accuracy (bias %) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Intra-day (4 replicates) | Inter-day (3 days) (4 replicates per day) | Intra-day (4 replicates) | Inter-day (3 days) (4 replicates per day) | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Average | SD | Average | SD | |||||

| Monkey | 0.18 | 0.2110 | 0.0004 | 0.2102 | 0.0007 | 0.1793 | 0.3246 | 17.9935 |

| 0.29 | 0.3072 | 0.0005 | 0.3048 | 0.0021 | 0.1591 | 0.6902 | 7.3783 | |

| 1.79 | 1.7491 | 0.0124 | 1.7475 | 0.0051 | 0.7063 | 0.2904 | −2.1743 | |

| 4.50 | 5.0675 | 0.0231 | 5.0773 | 0.0220 | 0.4554 | 0.4333 | 13.3670 | |

| Human | 0.18 | 0.1999 | 0.0002 | 0.1995 | 0.0008 | 0.0780 | 0.3917 | 11.7924 |

| 0.29 | 0.2854 | 0.0002 | 0.2859 | 0.0006 | 0.0816 | 0.2121 | −0.2565 | |

| 1.79 | 1.7737 | 0.0118 | 1.7808 | 0.0063 | 0.6635 | 0.3542 | −0.8008 | |

| 4.50 | 5.1902 | 0.0238 | 5.2379 | 0.0519 | 0.4607 | 0.7654 | 15.7538 | |

3.2.4 Extraction efficiency

The efficiency of the extraction method was measured for three different concentrations (0.18, 0.36, and 3.6 μg/mL) of Cp40 and a single concentration (0.36 μg/mL) of the IS. Average extraction recoveries in NHP plasma were above 81.9 ± 2.9% for all tested concentrations (Table 2); extraction recoveries in human plasma displayed values higher than 87.8 ± 10.37%. These values were not affected by SPE columns in blank samples, and therefore the peptides displayed recovery values indicating only minor matrix ion suppression effects in the human and NHP plasma samples.

Table 2.

Extraction recovery of Cp40 spiked into human and NHP plasma.

| Plasma | Concentration (μg/mL) |

Extraction recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Monkey | 0.18 | 87.0 ± 28.6 |

| 0.29 | 88.6 ± 12.5 | |

| 1.79 | 91.3 ± 10.2 | |

| 4.50 | 81.9 ± 2.9 | |

| Human | 0.18 | 91.7 ± 29.2 |

| 0.29 | 94.5 ± 14.3 | |

| 1.79 | 100.8 ± 11.8 | |

| 4.50 | 87.8 ± 10.4 |

3.2.5 Stability

In order to allow for reproducible analysis, the extracted Cp40 samples need to be stable during preparation and analysis. The stability of Cp40 after SPE extraction from plasma was assessed in conditions reflecting benchtop and autosampler storage. The Cp40 and IS concentrations remained stable during storage at both room temperature and 4°C for at least 48 h (Table 3). Recoveries for the three concentrations of spiked Cp40 in both NHP and human plasma at room temperature and 4°C were above 97%, and there was no observable decrease between 24 h and 48 h. Of note, cyclic peptides of the compstatin family have previously shown high stability even in complex biological matrices such as human plasma [19,20].

Table 3.

Stability of three QC standards of Cp40 spiked into human and NHP plasma samples under various handling and storage conditions.

| Plasma | Test conditions | Temperature (°C) |

Concentration (μg/mL) |

Recovery ± SD (n = 3) (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24h | 48h | ||||

| Monkey | Bench-top | 25 | 0.18 | 98.9 ± 1.3 | 100.4 ± 0.5 |

| 0.36 | 98.4 ± 0.5 | 99.5 ± 0.3 | |||

| 3.58 | 102.9 ± 7.8 | 101.6 ± 4.0 | |||

| Autosampler | 4 | 0.18 | 99.9 ± 0.4 | 100.2 ± 0.2 | |

| 0.36 | 98.7 ± 0.1 | 99.3 ± 0.4 | |||

| 3.58 | 99.0 ± 0.3 | 100.8 ± 0.3 | |||

| Human | Bench-top | 25 | 0.18 | 99.8 ± 0.3 | 99.3 ± 2.3 |

| 0.36 | 100.3 ± 0.9 | 100.1 ± 0.1 | |||

| 3.58 | 99.7 ± 0.9 | 99.7 ± 0.3 | |||

| Autosampler | 4 | 0.18 | 100.0 ± 1.3 | 99.6 ± 0.3 | |

| 0.36 | 97.5 ± 5.1 | 100.5 ± 0.6 | |||

| 3.58 | 99.4 ± 0.2 | 99.4 ± 0.3 | |||

3.2.6 Cp40 quantitation for the pharmacokinetic analysis in cynomolgus monkey plasma

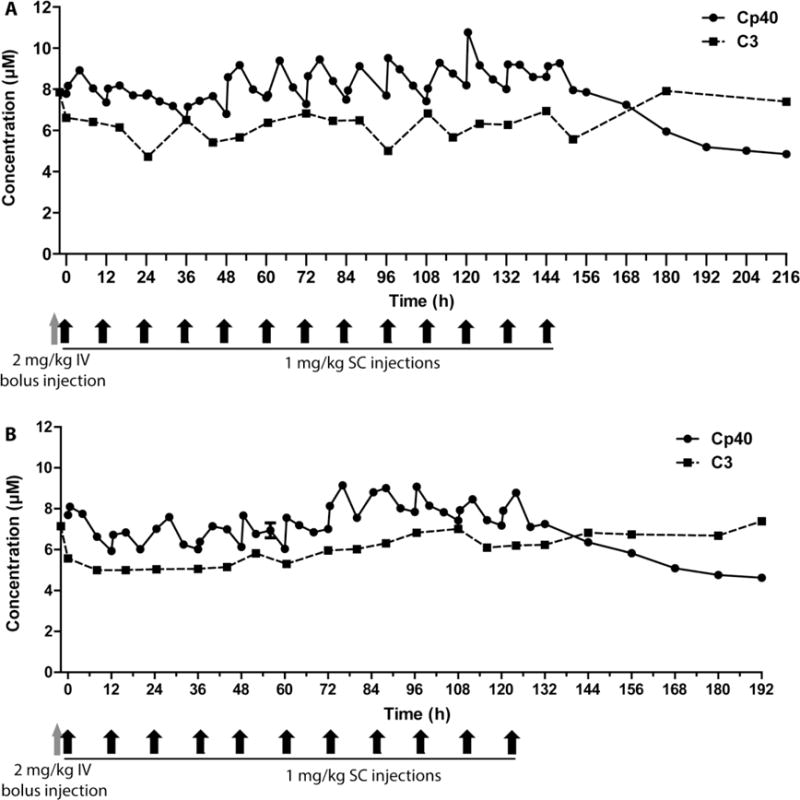

The optimized and validated UPLC-ESI-MS method was evaluated in a small-scale PK study in two cynomolgus monkeys (one male, one female), based on repetitive subcutaneous administration of Cp40 (Fig. 4). To achieve optimum therapeutic efficacy, the target protein C3 should remain saturated during the treatment period, thereby preventing C3 cleavage by C3 convertases and subsequent complement activation and/or amplification [8]. Given the 1:1 binding of the Cp40 to C3 [4], a molar excess of Cp40 should therefore be maintained. Whereas indications such as hemodialysis-induced inflammation may be treated with single injections of Cp40, other conditions such as transplant rejection or PNH would require mid- or long-term treatment plans.

Fig. 4.

Quantitation of Cp40 in plasma of a male (A) and a female (B) cynomolgus monkey. Graphs represent a linear plot of Cp40 concentration over time, measured by UPLC-ESI-MS: A single intravenous bolus injection of 2 mg/kg was followed 2 h later by the first subcutaneous injection (1 mg/kg) at time point 0; subcutaneous injections continued every 12 h for 6 days. The C3 concentration, as determined by nephelometry, is depicted as a dashed line. Concentrations are expressed in μM in order to allow us to assess the drug-to-target ratio. Injection time points are shown in gray and black arrows at the bottom of the graphs.

Based on previous experience with the administration of Cp40 in NHP [4,8], we therefore investigated the potential of maintaining target-saturating levels of Cp40 over an extended period of time. A study design was conceived that included an initial bolus dose of 2 mg/kg, administered intravenously, followed by repetitive subcutaneous injections at 1 mg/kg every 12 h for 6 days (Fig. 4). In order to assess the drug-to-target ratio and the maintenance of therapeutic compound levels, the concentration of Cp40 in plasma was monitored by UPLC-ESI-MS, and the C3 levels were measured by nephelometry. The average C3 concentration was ~6 μM in both animals (6.1 ± 0.8 and 6.3 ± 0.8 μM, respectively), which is in the expected range and similar as reported for human plasma (~7 μM). Using the dosing scheme mentioned above, target-saturating Cp40 levels of ~8 μM were quickly reached after the initial intravenous bolus injection, and the Cp40 concentration remained in excess of C3 during the entire subcutaneous treatment period. Each injection resulted in rising Cp40 concentrations within 0.5 to 4 h, followed by a steady yet incomplete elimination phase; the drug levels thereby fluctuated between 6.0 and 10.8 μM (Fig. 4). Following the final Cp40 injection, drug levels decreased steadily indicating clearance of the compound. The PK profile was similar in both animals and showed no obvious differences between the two sexes. As observed in previous studies [4,8], treatment with Cp40 did not notably affect the plasma levels of C3, which showed expected fluctuation but stayed in an expected range for the entire treatment period. Overall, the in vivo study indicated a favorable PK behavior of Cp40 after repetitive subcutaneous treatment, and the dosing scheme employed appeared suitable for treatment over several days.

The data also confirm and extend previous studies that showed biphasic, target-driven elimination after intravenous injection, with a more sustained profile following subcutaneous administration [4,8]. The single intravenous bolus injection of 2 mg/kg is important for rapidly achieving target-saturating concentrations. Indeed, we have previously shown that 2–3 injection cycles are needed to reach full saturation at subcutaneous doses of 1 mg/kg every 12 h in the absence of a bolus [8]. Moreover, our study was restricted to four consecutive injections, limiting the evaluation of longer-term sustenance. Importantly, we now show that therapeutic concentrations can be reliably maintained with this dosing scheme over the entire course of the study (i.e., 6 days). This PK study should provide valuable information for the administration of Cp40 in diseases that require long-term systemic treatment, such as PNH and C3G [21,22]. As was observed previously, the therapy was well tolerated by the animals, with no obvious adverse effects.

This study underscores the suitability of our UPLC-ESI-MS method for monitoring the Cp40 concentration in PK studies and disease models during further pre-clinical development of the compound. We have shown that our developed and validated method is robust, reproducible, selective, and sensitive and can be successfully applied to quantitative determination of Cp40 concentrations in plasma samples after administration in NHP. The highly comparable analytical profiles obtained for the NHP and human plasma samples suggest an easy transferability of the method to the monitoring of Cp40-based drugs in human volunteers and/or patients during clinical trials. It is anticipated that the same method may be applied to the analysis of Cp40 levels in other biological samples such as urine, after optimization of application-specific sample preparation steps. Finally, our method may prove beneficial for the development of similar analytical workflows in the monitoring of other compstatin analogs, or even unrelated compounds.

4. Conclusions

This is the first study of a combined SPE and UPLC-ESI-MS method that was developed and validated for the quantitation of Cp40, a second-generation analog of an emerging class of peptidic complement C3 inhibitors, in human and NHP plasma. Sample preparation and extraction were performed with good recovery rates, and the analytical method proved to be sensitive, selective, accurate, and precise. The optimized method was successfully applied to the quantitation of Cp40 in the plasma of treated cynomolgus monkeys in an extended PK study. The drug showed a favorable PK profile after an initial intravenous bolus injection of 2 mg/kg and repetitive subcutaneous injections of 1 mg/kg that saturated C3 levels for a prolonged time period, supporting a potential use for long-term complement inhibition. The method presented here may thus be applied to the preclinical and clinical development of Cp40-based drugs and may have implications for the analysis of other compstatin analogs, peptidic drugs, or other compounds in biological samples.

Highlights.

This is the first study to develop and validate a solid-phase extraction and UPLC-ESI-MS method for the quantitation of the complement inhibitor Cp40, a compstatin analog, in human and non-human primate plasma.

The developed method was linear, accurate and precise.

The validated method was successfully applied to the quantitation of Cp40 and the investigation of its pharmacokinetic behavior in cynomolgus monkeys.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI068730, AI030040) and the National Science Foundation (No. 1423304) and by funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program under grant agreement number 602699 (DIREKT). We thank Dr. Deborah McClellan for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- C3G

C3 glomerulopathy

- CF

correction factor

- IS

internal standard

- LLOQ

lower limit of quantitation

- NHP

non-human primate

- PD

pharmacodynamics

- PK

pharmacokinetic

- PNH

paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- QC

quality control

- SPE

solid-phase extraction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

D.R. and J.D.L. are the inventors of patents and/or patent applications that describe the use of complement inhibitors for therapeutic purposes. J.D.L. is the founder of Amyndas Pharmaceuticals, which is developing complement inhibitors for clinical applications. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. Complement-a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:785–797. doi: 10.1038/ni.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ricklin D, Reis ES, Lambris JD. Complement in disease: a defence system turning offensive. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:383–401. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan BP, Harris CL. Complement, a target for therapy in inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:857–877. doi: 10.1038/nrd4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qu H, Ricklin D, Bai H, Chen H, Reis ES, Maciejewski M, Tzekou A, DeAngelis RA, Resuello RR, Lupu F, Barlow PN, Lambris JD. New analogues of the clinical complement inhibitor compstatin with subnanomolar affinity and enhanced pharmacokinetic properties. Immunobiology. 2013;218:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mastellos DC, Yancopoulou D, Kokkinos P, Huber-Lang M, Hajishengallis G, Biglarnia AR, Lupu F, Nilsson B, Risitano AM, Ricklin D, Lambris JD. Compstatin: a C3-targeted complement inhibitor reaching its prime for bedside intervention. Eur J Clin Invest. 2015;45:423–440. doi: 10.1111/eci.12419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricklin D, Lambris JD. Therapeutic control of complement activation at the level of the central component C3. Immunobiology. 2016;221:740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mastellos DC, Ricklin D, Yancopoulou D, Risitano A, Lambris JD. Complement in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: exploiting our current knowledge to improve the treatment landscape. Expert Rev Hematol. 2014;7:583–598. doi: 10.1586/17474086.2014.953926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Risitano A, Ricklin D, Hang Y, Reis ES, Chen H, Ricci P, Lin Z, Pascariello C, Raia M, Sica M, Vecchio LD, Pane F, Lupu F, Notaro R, Resuello RR, DeAngelis RA, Lambris JD. Peptide inhibitors of C3 activation as a novel strategy of complement inhibition for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2014;123:2094–2101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-536573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Shao D, Ricklin D, Hilkin BM, Nester CM, Lambris JD, Smith RJ. Compstatin analog Cp40 inhibits complement dysregulation in vitro in C3 glomerulopathy. Immunobiology. 2015;220:993–998. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reis E, DeAngelis R, Chen H, Resuello R, Ricklin D, Lambris JD. Therapeutic C3 inhibitor Cp40 abrogates complement activation induced by modern hemodialysis filters. Immunobiology. 2015;220:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maekawa T, Abe T, Hajishengallis E, Hosur KB, DeAngelis R, Ricklin D, Lambris JD, Hajishengallis G. Genetic and intervention studies implicating complement C3 as a major target for the treatment of periodontitis. J Immunol. 2014;192:6020–6027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maekawa T, Briones RA, Resuello RR, Tuplano JV, Hajishengallis Ε, Kajikawa Τ, Koutsogiannaki S, Garcia CA, Ricklin D, Lambris JD, Hajishengallis G. Inhibition of preexisting natural periodontitis in non-human primates by a locally administered peptide inhibitor of complement C3. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43:238–249. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajishengallis G, Hajishengallis E, Kajikawa T, Wang B, Yancopoulou D, Ricklin D, Lambris JD. Complement inhibition in pre-clinical models of periodontitis and prospects for clinical application. Semin Immunol. 2016;28:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brun V, Masselon C, Garin J, Dupuis A. Isotope dilution strategies for absolute quantitative proteomics. J Proteomics. 2009;72:740–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciccimaro E, Blair IA. Stable-isotope dilution LC-MS for quantitative biomarker analysis. Bioanalysis. 2010;2:311–341. doi: 10.4155/bio.09.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation. 2013 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm368107.pdf.

- 17.Sargent M, Harrington C, Harte R. Guidelines for Achieving High Accuracy in Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry (IDMS) The Royal Society of Chemistry. Cambridge: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Compendium of Chemical Terminology. Gold Book; 2014. Version 2.3.3. http://goldbook.iupac.org/PDF/goldbook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahu Α, Soulika AM, Morikis D, Spruce L, Moore WT, Lambris JD. Binding kinetics, structure-activity relationship, and biotransformation of the complement inhibitor compstatin. J Immunol. 2000;165:2491–2499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knerr PJ, Tzekou A, Ricklin D, Qu H, Chen H, van der Donk WA, Lambris JD. Synthesis and activity of thioether-containing analogues of the complement inhibitor compstatin. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:753–760. doi: 10.1021/cb2000378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Risitano AM. Anti-Complement Treatment in Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria: Where we Stand and Where we are Going. Transl Med UniSa. 2014;8:43–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zipfel PF, Skerka C, Chen Q, Wiech T, Goodship T, Johnson S, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Nester C, de Córdoba SR, Noris M, Pickering M, Smith R. The role of complement in C3 glomerulopathy. Mol Immunol. 2015;67:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]