Abstract

Purpose

Genetic predisposition to male breast cancer (MBC) is not well understood. The aim of this study was to better define the predisposition genes contributing to MBC and the utility of germline multi-gene panel testing (MGPT) for explaining the etiology of MBCs.

Methods

Clinical histories and molecular results were retrospectively reviewed for 715 MBC patients who underwent MGPT from March 2012 to June 2016.

Results

The detection rate of MGPT was 18.1% for patients tested for variants in 16 breast cancer susceptibility genes and with no prior BRCA1/2 testing. BRCA2 and CHEK2 were the most frequently mutated genes (11.0 and 4.1% of patients with no prior BRCA1/2 testing, respectively). Pathogenic variants in BRCA2 [odds ratio (OR) = 13.9; p = 1.92 × 10−16], CHEK2 (OR = 3.7; p = 6.24 × 10−24), and PALB2 (OR = 6.6, p = 0.01) were associated with significantly increased risks of MBC. The average age at diagnosis of MBC was similar for patients with (64 years) and without (62 years) pathogenic variants. CHEK2 1100delC carriers had a significantly lower average age of diagnosis (n = 7; 54 years) than all others with pathogenic variants (p = 0.03). No significant differences were observed between history of additional primary cancers (non-breast) and family history of male breast cancer for patients with and without pathogenic variants. However, patients with pathogenic variants in BRCA2 were more likely to have a history of multiple primary breast cancers.

Conclusion

These data suggest that all MBC patients regardless of age of diagnosis, history of multiple primary cancers, or family history of MBC should be offered MGPT.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10549-016-4085-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Male breast cancer, Multi-gene panel testing, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2

Introduction

While the incidence of male breast cancer (MBC) in the general population is low (1:1000), it can be significantly elevated for patients with an underlying genetic predisposition. Comprehensive genetics evaluation of all MBC patients is important, as identification of various cancer-predisposing mutations can drastically impact medical management for patients and their family members. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, implicated in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC), have been associated with increased risks for MBC, and it is currently recommended that individuals with a personal or family history of male breast cancer undergo testing of these genes [1]. BRCA2 is the most frequently mutated gene in MBC cohorts, having been reported in 4–40% of MBC patients, depending on the population studied and the presence/absence of additional clinical history supporting a diagnosis of HBOC [2–9]. Cumulative lifetime breast cancer risks for male BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers are 1–2 and 5–10%, respectively. In addition to breast cancer, males with BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variants face increased lifetime risks for prostate and pancreatic cancers [10–12].

Beyond BRCA1/BRCA2, data are limited regarding genetic predisposition to MBC. Two independent studies have linked CHEK2 1100delC with MBC [13, 14]; however, results from multiple other studies have not confirmed this association [15–22]. Furthermore, the role of other CHEK2 pathogenic variants in MBC is yet to be explored. Germline pathogenic variants in the PTEN, androgen receptor (AR), NF1, and PALB2 genes have also been reported in MBC patients; however, associations with MBC have not been well-studied and risk estimates are not currently available [23–26].

The clinical availability of multi-gene panel testing (MGPT) presents an opportunity for patients to undergo comprehensive analysis of a wide range of cancer susceptibility genes, including those with and without established links to MBC. Despite increased utilization of such testing in hereditary cancer diagnostics, data remain limited regarding the yield of such testing for MBC patients. In a recent study of breast cancer patients who underwent MGPT, 31.8% (n = 7/22) of MBC cases tested positive for pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants: BRCA1 (1), BRCA2 (3), PALB2 (1), CHEK2 (1), and ATM (1) [8]. These results are yet to be validated in larger MBC cohorts. To better understand the genetic contribution to MBC and the yield of MGPT in this population, we retrospectively assessed a cohort of MBC patients referred for MGPT.

Methods

Study population

Clinical histories and molecular results were retrospectively reviewed for all MBC patients (n = 715) who underwent MGPT at Ambry Genetics between March 2012 and June 2016 (Aliso Viejo, CA). The following demographic and clinical history information was obtained from test requisition forms and clinic notes submitted by ordering providers: age at testing, ethnicity, BRCA1/2 testing history, and personal/family cancer history. Patients were excluded if they were known BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers prior to MGPT (n = 1), if heterozygosity ratios of less than <25% were observed for any reported alterations detected in the patient (n = 3), or if the only information suggesting a MBC diagnosis was an ICD-9 code (n = 3), leaving 708 MBC patients eligible for further study.

Laboratory methods

Patients underwent comprehensive analysis of cancer susceptibility genes using a variety of gene panels (Online Resource 1). Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (gDNA) was isolated from the patient’s blood or saliva specimen using a standardized methodology (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and quantified by spectrophotometer (Nanodrop; Thermoscientific, Pittsburgh, PA, or Infinite F200; Tecan, San Jose, CA). Sequence enrichment was performed by incorporating the gDNA onto a microfluidics chip or into microdroplets along with primer pairs or by a bait-capture methodology using long biotinylated oligonucleotide probes (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, CA, RainDance Technologies, Billerica, MA or Integrated DNA Technologies, San Diego, CA), followed by PCR and NGS analysis (Illumina, San Diego, CA) of all coding regions ± five bases into introns and untranslated regions (5′UTR and 3′UTR). Sanger sequencing was performed for any regions with insufficient depth of coverage for reliable heterozygous variant detection and for verification of variant calls, other than known non-pathogenic alterations. A targeted chromosomal microarray was used for the detection of gross deletions and duplications for each sample (Aglient, Santa Clara, CA). Initial data processing and base calling were performed with RTA 1.12.4 (HiSeq Control Software 1.4.5; Illumina). Sequence quality filtering was executed with CASAVA software (version 1.8.2; Illumina, Hayward, CA). Sequence fragments were aligned to the reference human genome (GRCh37), and variant calls were generated using CASAVA. A minimum quality threshold of Q20 was applied, translating to an accuracy of >99.9% for the called bases.

Variant classification

Variants were annotated with the Ambry Variant Analyzer, a proprietary alignment and variant annotation software (Ambry Genetics) that assigned variants according to a five-tier variant classification protocol [pathogenic mutation; variant, likely pathogenic (VLP); variant of unknown significance (VUS); variant, likely benign (VLB); and benign], based on published recommendations from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the International Agency for Research on Cancer [27–29].

Statistical analysis

The frequency of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants was calculated for ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, MRE11A, NBN, NF1, PALB2, PTEN, RAD50, RAD51C, RAD51D, and TP53. To avoid potential bias introduced by prior BRCA1/2 testing and the varying number of genes tested by panel type, the diagnostic yield of MGPT was assessed using MBC patients tested for all 16 breast cancer genes (n = 512) and then stratified by prior BRCA1/2 testing status. Clinical history comparisons were performed using patients tested for all 16 breast cancer genes, after removal of cases with pathogenic variants in genes not associated with breast cancer (n = 6), multiple pathogenic variants in breast cancer genes (n = 5), patients with monoallelic MUTYH pathogenic variants as the only pathogenic variant detected (n = 5), and patients carrying the low-risk CHEK2 p.I157T variant (n = 6). Multivariable logistic regression (controlling for age, ethnicity and panel ordered) was performed to compare personal history of additional primary cancers and family history of MBC. A two-sample t test was used to test the age difference between groups.

Breast cancer risk estimation

Among 708 MBC patients, 538 were Caucasian or Ashkenazi Jewish. Of these, individuals tested for all 16 breast cancer predisposition genes (n = 421) were subjected to breast cancer risk estimation. The non-Finn European population (NFE) in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) dataset [30], excluding The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) exomes, were used as public controls for case–control association studies with Caucasian breast cancer cases, consistent with the effective use of this dataset for estimation of ovarian and prostate cancer risk in recent studies [31, 32]. ExAC filter PASS/non-PASS rather than PASS only variants from the ExAC NFE-non TCGA dataset were used because multiple pathogenic variants validated by Ambry Genetics were excluded from the filter PASS category of ExAC. Restricting to PASS only variants led to reduced numbers of variants in controls and inflated breast cancer risks associated with each gene. To account for low-quality ExAC variants, recurrent variants observed at significantly different frequencies in other populations or with sequence misalignment were excluded. All remaining loss of function variants (nonsense, frameshift, consensus dinucleotide splice site (±1 or 2), and any missense variants defined as pathogenic in ClinVar by clinical laboratories) in breast cancer cases and ExAC controls were selected for inclusion. A series of filtering steps were applied (Supplementary Methods) to normalize differences in the breast cancer cases and the ExAC controls. Breast cancer cases carrying two or more pathogenic variants were excluded because of potential for inflation of breast cancer risks. While this filter was not applied to ExAC data due to the absence of individual-level genotype data, these events are rare in the general population and should only have a minor, conservative impact on risks estimates. Similarly, large genomic rearrangements of one or more exons were excluded from cases and ExAC controls because rearrangements were not validated among controls. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted when restricting to cases without prior BRCA1/2 testing, to account for ascertainment bias (n = 268). Associations with breast cancer were estimated using the Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Demographics

This cohort was primarily Caucasian (66.1%), with other ethnicities each representing ≤10% of patients tested (Table 1). Ethnicity was unspecified for 6.2% of the cohort. The majority of patients were aged 60 and older at the time of testing (71.7%) and at the time of first breast cancer diagnosis (61.0%). Four percent of MBC patients had a second primary breast cancer, and additional non-breast primary cancers were reported for 23.4%. The most common additional cancer was prostate cancer, which was significantly enriched in this cohort with a frequency of 9.5% (n = 67) compared with the general population (0.13%; p = 10−16) [33]. A family history of MBC was reported for 6.4% of patients.

Table 1.

Demographics of overall male breast cancer cohort (n = 708)

| Demographic | N | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 468 | 708 | 66.1 |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 70 | 708 | 9.9 |

| African American | 58 | 708 | 8.2 |

| Asian | 23 | 708 | 3.2 |

| Hispanic | 16 | 708 | 2.3 |

| Middle Eastern | 5 | 708 | 0.7 |

| Native American | 1 | 708 | 0.1 |

| Mixed ethnicity | 20 | 708 | 2.8 |

| Other | 3 | 708 | 0.4 |

| Unknown | 44 | 708 | 6.2 |

| Panel ordered (total number of genes on panel) | |||

| BRCAplus (5–6) | 115 | 708 | 16.2 |

| GYNplus (9–13) | 7 | 708 | 1.0 |

| BRCAplus-expanded | 17 | 708 | 2.4 |

| BreastNext (14–18) | 297 | 708 | 41.9 |

| OvaNext (19–24) | 66 | 708 | 9.3 |

| PancNext (range) | 5 | 708 | 0.7 |

| CancerNext (22–32) | 148 | 708 | 20.9 |

| CancerNext-expanded (43–49) | 53 | 708 | 7.5 |

| Age at testing | |||

| 20–29 | 2 | 708 | 0.3 |

| 30–39 | 18 | 708 | 2.5 |

| 40–49 | 43 | 708 | 6.1 |

| 50–59 | 138 | 708 | 19.5 |

| 60–69 | 234 | 708 | 33.1 |

| 70–79 | 189 | 708 | 26.7 |

| 80–89 | 75 | 708 | 10.6 |

| 90 and older | 9 | 708 | 1.3 |

| Age at diagnosisa | |||

| 20–29 | 10 | 687 | 1.5 |

| 30–39 | 28 | 687 | 4.1 |

| 40–49 | 70 | 687 | 10.2 |

| 50–59 | 160 | 687 | 23.3 |

| 60–69 | 210 | 687 | 30.6 |

| 70–79 | 158 | 687 | 23.0 |

| 80–89 | 47 | 687 | 6.8 |

| 90 and older | 4 | 687 | 0.6 |

| Testing history | |||

| Prior BRCA1/2 testing | 223 | 708 | 31.5 |

| Clinical Historya | |||

| Family history male breast cancer | 41 | 643 | 6.4 |

| Multiple primary breast cancers | 28 | 706 | 4.0 |

| Additional non-breast primary cancers | 166 | 708 | 23.4 |

aAge at diagnosis and clinical history were not provided for all men in the cohort

Test results

Ninety-seven of 708 MBC patients were found to have at least one pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in a breast cancer susceptibility gene (Table 2). Seven of these patients were found to carry two pathogenic variants including one biallelic ATM carrier with a clinical diagnosis of ataxia-telangiectasia, two ATM/BRCA2 carriers, one BRIP1/BRCA2 carrier, one BRCA1/CHEK2 carrier, one BARD1/PALB2 carrier, and one CHEK2/PALB2 carrier. BRCA2 and CHEK2 were the most frequently altered genes, with pathogenic variants identified in 11.0 and 4.1% of MBC patients with no prior BRCA1/2 testing, respectively (Table 3). No pathogenic variants were identified in the following hereditary breast cancer genes: CDH1, PTEN, RAD50, RAD51C, and TP53.

Table 2.

Clinical histories of mutation carriers (N = 97)

| Positive gene(s) | Pathogenic variant(s) | First breast cancer age | Bilateral/multiple breast cancers | Other cancer(s) | Family history of MBCa | Ethnicity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATM | p.K2756* | 70–79 | No | Liver/melanoma/prostate | NP | Caucasian | |

| ATM | p.R2832C | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| ATM | c.901+1G>A | 70–79 | No | No | Hispanic | ||

| ATM/ATM | c.5763-1050A>G/c.8418+5_8418+8delGTGA | 50–59 | No | No | Caucasian | AT clinical dx | |

| ATM/BRCA2 | p.W2638*/c.5616_5620delAGTAA | 70–79 | No | Prostate | No | African American | |

| ATM/BRCA2 | p.Q2651*/p.Q548* | 80–89 | No | Skin | No | Caucasian | |

| BARD1 | p.Q564* | 70–79 | No | NP | Caucasian | ||

| BARD1/PALB2 | c.1935_1954dup20/c.109-2A>G | 50–59 | No | Yes | Unknown | ||

| BRCA1 | EX11_13del | 50–59 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA1 | p.C61G | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA1 | EX11_13del | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA1 | c.5266dupC | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA1 | c.3481_3491del11 | 60–69 | No | Liver | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA1/CHEK2 | c.5177_5180delGAAA/c.1100delC | 40–49 | No | No | African American | ||

| BRCA2 | 5′UTR_EX1del | 50–59 | No | Bladder | NP | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.5576_5579delTTAA | 60–69 | No | NP | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | c.9253dupA | 60–69 | No | NP | African American | ||

| BRCA2 | p.R2520* | 60–69 | Yes | NP | Middle Eastern | ||

| BRCA2 | c.1813dupA | 70–79 | No | Prostate | NP | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | 5′UTR_EX1del | 60–69 | No | Gastroesophageal | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.518delG | 60–69 | No | Leukemia | No | African American | |

| BRCA2 | c.1296_1297delGA | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | p.D2723H | 30–39 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | c.7865dupA | 40–49 | No | Bladder | No | Asian | |

| BRCA2 | c.4456_4459delGTTA | 40–49 | Yes | No | African American | ||

| BRCA2 | c.3257_3258delTA | 40–49 | Yes | No | African American | ||

| BRCA2 | c.5164_5165delAG | 50–59 | No | No | African American | ||

| BRCA2 | c.5722_5723delCT | 50–59 | No | Tonsil/NOS | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.5946delT | 50–59 | No | Ureter | No | Ashkenazi Jewish | |

| BRCA2 | 5′UTR_EX15del | 50–59 | No | No | Ashkenazi Jewish | ||

| BRCA2 | c.8297delC | 50–59 | No | Lymphoma | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.8297delC | 50–59 | No | Skin | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.8331+1G>A | 50–59 | No | Pancreas/melanoma | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | p.E1953* | 50–59 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | c.6938-1G>A | 50–59 | No | Tonsil | No | Mixed ethnicity | |

| BRCA2 | c.5799_5802delCCAA | 60–69 | No | No | Hispanic | ||

| BRCA2 | c.5130_5133delTGTA | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | 5′UTR_EX1del | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | c.6676_6677delGA | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | c.5722_5723delCT | 60–69 | No | Prostate | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.7977-1G>C | 60–69 | No | Yes | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | c.6591_6592delTG | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | c.4940_4941delCA | 60–69 | No | No | Mixed ethnicity | ||

| BRCA2 | p.E1308* | 60–69 | No | No | Unknown | ||

| BRCA2 | c.1813dupA | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | c.5350_5351delAA | 60–69 | Yes | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | p.V159M | 60–69 | No | No | Hispanic | ||

| BRCA2 | c.9117G>A | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | p.R2336P | 60–69 | No | No | Other | ||

| BRCA2 | c.8374_8384del11insAGG | 60–69 | No | Prostate | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | p.R2520* | 70–79 | No | Prostate | Yes | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | p.E3111* | 70–79 | Yes | Yes | African American | ||

| BRCA2 | c.4876_4877delAA | 70–79 | Yes | Colon/lymphoma | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.778_779delGA | 70–79 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | p.R2659K | 70–79 | No | Prostate | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.3975_3978dupTGCT | 70–79 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | p.Q2859* | 70–79 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | p.E49* | 70–79 | No | No | Mixed ethnicity | ||

| BRCA2 | c.9435_9436delGT | 70–79 | No | Melanoma/skin | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.6068_6072delACCAG | 70–79 | No | Bladder | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.1929delG | 70–79 | No | Melanoma/skin | No | Caucasian | |

| BRCA2 | c.3975_3978dupTGCT | 70–79 | No | Colon/lung | Yes | Unknown | |

| BRCA2 | p.Q3026* | 90–99 | No | Yes | Mixed ethnicity | ||

| BRCA2 | p.R2520* | 90–99 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| BRCA2 | c.5946delT | NOS | No | No | Unknown | ||

| BRCA2 | c.4876_4877delAA | NOS | Yes | No | Hispanic | ||

| BRCA2/BRIP1 | c.2808_2811delACAA/p.R798* | 70–79 | No | Yes | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | c.591delA | 60–69 | No | NP | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | p.R117G | 40–49 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | c.1100delC | 40–49 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | c.1100delC | 40–49 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | c.1100delC | 40–49 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | p.T476M | 50–59 | No | Melanoma | No | Unknown | |

| CHEK2 | c.1100delC | 50–59 | No | Kidney | No | Caucasian | |

| CHEK2 | p.I157T | 50–59 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | p.T476M | 50–59 | No | Colon | No | Caucasian | |

| CHEK2 | p.I157T | 50–59 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | c.1100delC | 50–59 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | p.I157T | 50–59 | No | No | Ashkenazi Jewish | ||

| CHEK2 | c.1100delC | 60–69 | No | Leukemia | No | Caucasian | |

| CHEK2 | p.S428F | 60–69 | No | No | Ashkenazi Jewish | ||

| CHEK2 | c.1100delC | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | p.Q29* | 70–79 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | p.S428F | 70–79 | No | Yes | Ashkenazi Jewish | ||

| CHEK2 | p.I157T | 70–79 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | p.I157T | 70–79 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2 | c.1100delC | <59 | No | Yes | Caucasian | ||

| CHEK2/PALB2 | p.I157T/c.172_175delTTGT | 70–79 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| MRE11A | c.1867+2T>C | 70–79 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| NBN | c.657_661delACAAA | 70–79 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| NF1 | p.R1276* | 50–59 | No | NP | African American | ||

| NF1 | p.Q1070* | 30–39 | No | No | African American | NF1 clinical dx | |

| NF1 | c.1721+3A>G | 40–49 | No | Leukemia/pheochromocytoma/lymphoma | No | Mixed ethnicity | Son noted to have NF1 clinical dx |

| PALB2 | c.661_662delinsTA | 50–59 | No | Thyroid | No | Caucasian | |

| PALB2 | p.Y1183* | 50–59 | No | No | Ashkenazi Jewish | ||

| PALB2 | c.93dupA | 60–69 | No | No | Caucasian | ||

| RAD51D | c.270_271dupTA | 80–89 | No | No | Asian |

a NP not provided

Table 3.

Frequency of pathogenic variants in breast cancer genes in overall MBC cohort (n = 708)

| Gene | No prior BRCA1/2 testing | Prior BRCA1/2 testing | All MBC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants | Total testeda | % | Total pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants | Total testeda | % | Total pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants | Total testeda | % | |

| BRCA2 | 53 | 480 | 11.0 | 2 | 197 | 1.0 | 55 | 677 | 8.1 |

| CHEK2 (all) | 16 | 386 | 4.1 | 6 | 195 | 3.1 | 22 | 581 | 3.8 |

| CHEK2 (excluding I157T) | 11 | 386 | 2.8 | 5 | 195 | 2.6 | 16 | 581 | 2.8 |

| CHEK2 (I157T only) | 5 | 386 | 1.3 | 1 | 195 | 0.5 | 6 | 581 | 1.0 |

| ATM b | 6 | 390 | 1.5 | 0 | 196 | 0.0 | 6 | 586 | 1.0 |

| BRCA1 | 6 | 480 | 1.3 | 0 | 197 | 0.0 | 6 | 677 | 0.9 |

| NF1 | 2 | 354 | 0.6 | 1 | 158 | 0.6 | 3 | 512 | 0.6 |

| PALB2 | 2 | 417 | 0.5 | 3 | 204 | 1.5 | 5 | 621 | 0.8 |

| RAD51D | 1 | 354 | 0.3 | 0 | 158 | 0.0 | 1 | 512 | 0.2 |

| BRIP1 | 1 | 370 | 0.3 | 0 | 194 | 0.0 | 1 | 564 | 0.2 |

| MRE11A | 1 | 370 | 0.3 | 0 | 194 | 0.0 | 1 | 564 | 0.2 |

| NBN | 1 | 370 | 0.3 | 0 | 194 | 0.0 | 1 | 564 | 0.2 |

| BARD1 | 0 | 370 | 0.0 | 2 | 194 | 1.0 | 2 | 564 | 0.4 |

aThe total number of men tested varies by gene, as not all men were tested by the same panel of genes

b ATM biallelic individual was counted only once

Diagnostic yield

To assess the diagnostic yield of MGPT for MBC patients, results were analyzed for patients tested for all 16 breast cancer genes (n = 512) (Table 4). The overall mutation-positive rate for breast cancer susceptibility genes for patients with no prior BRCA1/2 testing reported was 18.1% (N = 64/354), with 1.1% (n = 4) of patients carrying pathogenic variants in two different breast cancer genes. The overall mutation-positive rate for breast cancer susceptibility genes for patients with prior BRCA1/2 testing reported was 7.6% (N = 12/158), with 1 patient carrying mutations in two different breast cancer genes. Of note, two patients in this group tested positive for BRCA2 gross deletions that were not previously detected because gross deletion/duplication analysis had not been previously performed.

Table 4.

Findings among MBC patients tested for 16 breast cancer genes (n = 512)

| Result category | No prior BRCA testing (n = 354) | Prior BRCA testing (n = 158) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant | 64 | 18.1 | 12 | 7.6 |

| Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant(s) in a single gene | 60a | 16.9 | 11 | 7.0 |

| BRCA1/2 | 39 | 11.0 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Non-BRCA1/2 | 21 | 5.9 | 9 | 5.7 |

| Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant(s) in multiple genes | 4 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Combination of BRCA1/2 and non-BRCA1/2 genes | 3 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Multiple non-BRCA1/2 genes | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant + VUS | 16 | 4.5 | 5 | 3.2 |

| VUS only | 59 | 16.7 | 34 | 21.5 |

| Negative | 231 | 65.3 | 112 | 70.9 |

a59 had a single pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant and 1 had biallelic ATM mutations

Clinical history comparisons

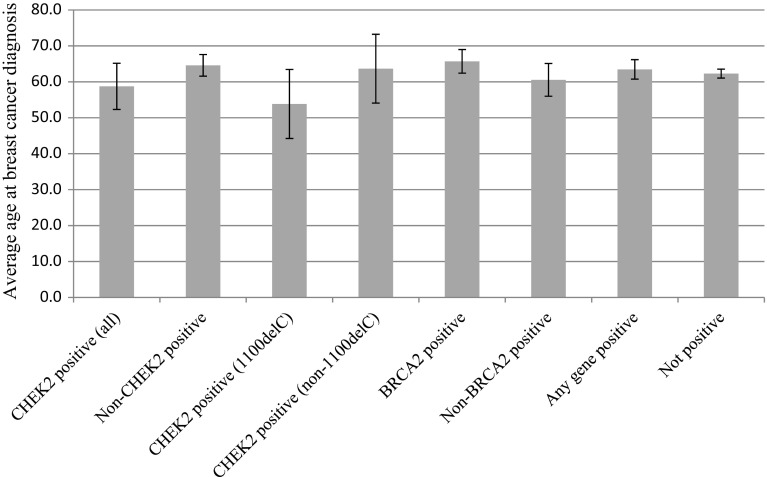

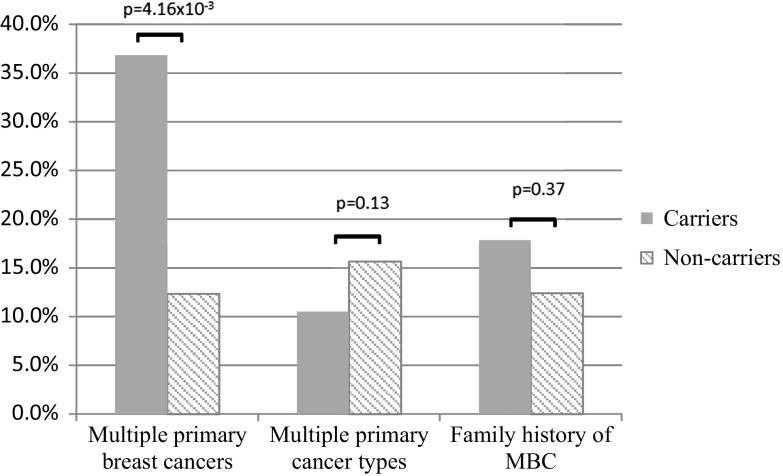

The average age of diagnosis was similar for men with (63.5 ± 2.7 years) and without (62.3 ± 1.2 years; p = 0.43) pathogenic variants (Fig. 1). In addition, there was no significant difference in history of multiple primary cancers between patients with and without pathogenic variants (p = 0.13) (Fig. 2). However, patients with pathogenic variants were more likely to report multiple primary breast cancers (p = 4.16 × 10−3), with BRCA2 accounting for all cases. There was no significant difference in family history of MBC (p = 0.37).

Fig. 1.

Average age at breast cancer diagnosis based on test result

Fig. 2.

Clinical histories of pathogenic carriers versus non-carriers

The average age of diagnosis for men with any CHEK2 pathogenic variants (58.8 ± 6.4 years) was not significantly different from men with non-CHEK2 pathogenic variants (64.6 ± 3.0 years; p = 0.09) or from men who did not test positive (62.3 ± 1.2 years; p = 0.26); however, CHEK2 1100delC carriers had a significantly lower average age of diagnosis (53.8 ± 9.6 years) compared to men with non-CHEK2 variants (p = 0.03). No significant differences were observed between average age at breast cancer diagnosis for CHEK2 1100delC carriers compared to other CHEK2 pathogenic variants (63.7 ± 9.6 years; p = 0.09) or to men who did not test positive (p = 0.07), though these trended toward significance.

Gene-specific risks of MBC

Case–control analyses were performed based on sequencing results from 421 Caucasian MBC patients and 26,911 ExAC NFE-non TCGA controls. Pathogenic variants in BRCA2 and CHEK2 were significantly associated with increased risk of MBC (BRCA2 OR = 13.9, p = 1.92 × 10−16; CHEK2 OR = 2.43, p = 1.82 × 10−3) (Table 5). Additional studies evaluating risks associated with CHEK2 1100delC and excluding common/low-risk missense variants (p.Ile157Thr and p.Ser428Phe) showed that truncating variants in CHEK2 are associated with moderately increased risks of MBC (OR = 3.8; 95% CI 2.1–6.8; p = 1.51 × 10−4) (Table 5). Variants in PALB2 were also significantly associated with a high risk of MBC (OR = 6.6, p = 0.013) (Table 5). However, this risk estimate is uncertain due to small numbers of MBCs with pathogenic variants (95% CI 1.70–21.09). Interestingly, few pathogenic variants were identified in ATM and BRCA1, which are commonly mutated in female familial breast cancer. No significant associations with MBC risks were observed. Sensitivity analyses excluding MBCs with prior testing of BRCA1/2 showed very similar effects for pathogenic variants in these genes (Online Resource 3).

Table 5.

Breast cancer risks associated with pathogenic variants pooled by gene among Caucasian male breast cancer cases

| Gene | Ambry cases | ExAC controls | Cancer risk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutated alleles | Cases | Mutated alleles | Cases | OR | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p value | |

| ATM | 2 | 421 | 90 | 26,644 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 5.1 | 0.66 |

| BRCA1 | 2 | 394 | 74 | 26,911 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 6.8 | 0.30 |

| BRCA2 | 21 | 394 | 105 | 26,791 | 13.9 | 8.5 | 22.5 | 1.92 × 10−16 |

| CHEK2 All | 17 | 421 | 424 | 25,215 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 1.82 × 10−3 |

| CHEK2_c.1100delC | 8 | 421 | 127 | 25,215 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 7.8 | 1.82 × 10−3 |

| CHEK2 W/O I157T/S428F | 10 | 421 | 163 | 25,215 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 7.0 | 6.24 × 10−4 |

| CHEK2 W/O I157T | 12 | 421 | 191 | 25,215 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 6.8 | 1.51 × 10−4 |

| CHEK2 I157T | 5 | 421 | 233 | 25,215 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 0.60 |

| PALB2 | 3 | 421 | 29 | 26,869 | 6.6 | 1.7 | 21.1 | 0.013 |

Discussion

Previously reported cohorts of MBC patients undergoing MGPT have included 22–51 cases [8, 9], making this the largest reported collection to date of MBC patients undergoing MGPT. As expected, BRCA2 accounted for the largest percentage of pathogenic variants, whereas the observed frequency of CHEK2 pathogenic variants (4.1%) was greater than expected based on previous reports of MBC in CHEK2 cohorts. These findings support recent reports of the CHEK2 pathogenic variant frequencies among MBC cases in the MGPT setting (4.5–7.8%) [8, 9]. While BRCA2 is an established MBC susceptibility gene, literature regarding an association of CHEK2 with MBC is conflicting. Despite an initial report in 2002 concluding that CHEK2 1100delC is associated with a tenfold risk for MBC [13], and a subsequent report of an association between 1100delC and MBC in the Dutch population [14], multiple other studies have not affirmed this association [15–22]. The limited number of probands affected with MBC (i.e., under 100 in most studies) and the lack of full sequencing of CHEK2 in published cohorts may explain these conflicting reports. In the current study, CHEK2 protein-truncating variants were associated with a 3.8-fold increased risk for MBC, which is highly consistent with findings from the studies of breast cancer families. Confidence intervals ranged from 2.1 to 6.8 suggesting that CHEK2 is a moderate risk gene for MBC. In contrast, BRCA2 pathogenic variants were associated with much higher risks of MBC (OR = 13.9; 95% CI 8.5–22.5).

Multiple ATM and PALB2 pathogenic variants were also detected among MBC patients in this cohort. To our knowledge, this is only the second report of MBC in ATM heterozygotes [8] and the first report of MBC in a patient with ataxia-telangiectasia. Of note, two of the five ATM pathogenic variant carriers in the refined 16-gene subgroup were multiple pathogenic variant carriers, including one ATM biallelic carrier and one ATM/BRCA2 carrier. In the larger cohort, there was also one additional ATM/BRCA2 carrier. Furthermore, ATM pathogenic variants were not significantly associated with MBC (Table 5). These observations suggest ATM may act as an MBC risk modifier. There are multiple previous reports of PALB2 pathogenic variants among MBC families, with a frequency ranging from 0.8 to 6.4%, although most reports have not met statistical significance [23, 34–37]. One study reported that PALB2 pathogenic variant carriers were four times more likely than PALB2-negative patients to have a relative with MBC (p < 0.001) [34]. In addition, Antoniou et al. reported an eightfold increased risk for MBC in PALB2 carriers from moderate- and high-risk families; however, this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08) [35]. Consistent with both reports, PALB2 pathogenic variants in the current study were associated with a 6.6-fold increased risk of MBC (Table 5). Further association studies, in families and in the general population, are needed to confirm the association of genes such as ATM and PALB2 with MBC and to calculate more precise breast cancer risks for males with pathogenic variants in these genes.

Five (1.41%) of the MBC patients in the refined subgroup with no prior BRCA testing carried multiple pathogenic variants. As mentioned above, one of the MBC patients had biallelic ATM pathogenic variants and was noted to have a clinical history of ataxia-telangiectasia on the requisition form. Three of the multiple pathogenic variant carriers had a combination of pathogenic variants in one high-risk gene and one moderate risk gene: BRCA1/CHEK2, BRCA2/ATM, and BRCA2/BRIP1. The other multiple pathogenic variant carriers had mutations in two moderate-risk genes: CHEK2/PALB2. Excluding skin cancer, only the BRCA2/ATM pathogenic variant carrier reported multiple primary cancers (MBC and prostate cancer). The percentage of multiple pathogenic variants in this cohort and other reported MBC cohorts appears to be similar to multiple pathogenic variants in female breast cancer cohorts [8, 9].

Due to the relatively low number of pathogenic variants in other non-breast cancer genes in this cohort, it is difficult to assess whether MBC is an unrecognized component of the cancer spectra for these genes. Interestingly, several men tested positive for a pathogenic variant in genes associated with a syndromic presentation, including APC and SDHA. These patients did not have classical presentation of the associated syndromic features, indicating that gene-specific testing likely would not have been considered (Online Resource 2). Breast cancer—male or female—is not currently considered a component of the cancer spectra for these genes. While identification of a pathogenic variant in these cases is likely to impact medical management for other cancers, the result offers little insight into the most appropriate management of MBC risk, specifically, or whether other males in the family should be considered for testing and/or high-risk breast cancer screening.

No PTEN pathogenic variants were detected among MBC probands, despite previous reports of PTEN carriers with MBC. Since PTEN pathogenic variants are typically associated with Cowden syndrome (i.e., the presence of macrocephaly and characteristic mucocutaneous features in addition to cancer predisposition), it is likely that MBC patients with clinical histories suggestive of Cowden syndrome would be referred for PTEN testing alone rather than MGPT. Therefore, the absence of PTEN mutations in this cohort does not necessarily contradict previous reports. Similarly, pathogenic variants were not identified in TP53 or CDH1 in this cohort. While male breast cancer is not a major feature associated with either of these genes, it is possible that men with clinical histories suggestive of Li–Fraumeni syndrome or Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer syndrome would have had single gene testing instead of MGPT, potentially introducing ascertainment bias with respect to these genes.

With the exception of men with CHEK2 1100delC, age of diagnosis was not predictive of positive test results. Although the number of men carrying the CHEK2 1100delC in this cohort is small, the significantly younger age of diagnosis in this subset may indicate that men with this specific pathogenic variant may warrant surveillance and/or a higher index of suspicion for male breast cancer at a younger age compared to men with other pathogenic variants. Family history of MBC and additional primary cancer diagnoses were also not predictive of positive results in this cohort, consistent with current NCCN BRCA1/2 testing guidelines which recommend testing for MBC patients regardless of age at diagnosis or other clinical history. In contrast, multiple breast primary cancers were only identified in BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers in this cohort, suggesting a role for first-line BRCA1/BRCA2 testing in men with this presentation.

The identification of pathogenic variants in MBC patients may have clinical implications both for the affected men and their relatives. For example, breast cancer screening is recommended for BRCA1/BRCA2-positive men, beginning at age 35, and increased colon surveillance is recommended for CHEK2-positive individuals [1]. Several of the pathogenic variants identified in this cohort are associated with risks for other cancers, and their identification allows for increased surveillance which may lead to earlier detection of subsequent cancers. Many of the pathogenic variants identified in this cohort also carry significant risks for breast and ovarian cancer in women. Therefore, identification of variants in MBC patients allows for testing at-risk family members and increased surveillance and/or risk-reducing surgeries for positive relatives. Given the clinical implications for patients and their families, there appears to be utility in choosing a MGPT approach for MBC patients.

There are several limitations to this study. While previous BRCA1/2 testing was controlled for in this analysis, it is possible that previous BRCA1/2 testing was underreported in this group. Clinical history was ascertained by information reported on test requisition forms, and were verified by pedigree review when provided. As such, the analysis of secondary cancers and family history of cancer may be limited by the accuracy and completeness of the data provided. However, results from a recent study demonstrated that clinical history on test requisition forms at Ambry Genetics is highly accurate and complete for probands and highly accurate for relatives, with completeness correlating with relationship to the proband (i.e., more complete for first- and second-degree relatives and less complete for third-degree relatives and beyond) [38]. In addition, as this is a retrospective review of men selected for different clinical genetic tests and may over-represent male breast cancer cases in the setting of a family history also indicative of a hereditary predisposition for cancer, the results of the study may be influenced by ascertainment bias or be specifically applicable to a high-risk population. Finally, segregation data in families with multiple cases of male breast cancer and in families with multiple pathogenic variants from this cohort are not available. Segregation data could potentially clarify the association between male breast cancer and the identified pathogenic variants in these families.

Results from this study build upon the current understanding of hereditary susceptibility to MBC. These data lend support to a MGPT approach for MBC patients regardless of age at diagnosis, history of multiple primary cancers, and family history of MBC. Furthermore, these data support CHEK2 as a MBC susceptibility gene. The observed pathogenic variant frequency in this MBC cohort highlights the immediate need for studies investigating the most appropriate screening and risk management tools for MBC patients, particularly in cases with pathogenic variants in genes beyond BRCA1/2.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was funded in part by NIH grants CA192393, CA116167, CA176785, an NCI Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in breast cancer, and the breast cancer research foundation.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Mary Pritzlaff, Pia Summerour, Shuwei Li, Patrick Reineke, Jill S. Dolinsky, Rachel McFarland, and Holly LaDuca are employees of Ambry Genetics. Jill S. Dolinsky and Elizabeth Chao are stock holders of Ambry Genetics. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study formal consent is not required. The research presented here complies with the current laws of the United States of America.

Research involving human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Mary Pritzlaff and Pia Summerour have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology™ Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian V2.2016. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2016. http://www.nccn.org/. Accessed 22 Sept 2016

- 2.Thorlacius S, Sigurdsson S, Bjarnadottir H, et al. Study of a single BRCA2 mutation with high carrier frequency in a small population. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60(5):1079–1084. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Couch FJ, Faird LM, SeSHano ML, et al. BRCA2 germline mutations in male breast cancer cases and breast cancer families. Nat Genet. 1996;13(1):123–125. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank TS, Deffenbaugh AM, Reid JE, et al. Clinical characteristics of individuals with germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: analysis of 10,000 individuals. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(6):1480–1490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.6.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwong A, Ng EK, Wong CL, et al. Identification of BRCA1/2 founder mutations in Southern Chinese breast cancer patients using gene sequencing and high resolution DNA melting analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e43994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Son BH, Ahn SH, Kim SW, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in non-familial breast cancer patients with high risks in Korea: the Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer (KOHBRA) Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(3):1143–1152. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2001-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gargiulo P, Pensabene M, Milano M, et al. Long-term survival and BRCA status in male breast cancer: a retrospective single-center analysis. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:375. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2414-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tung N, Battelli C, Allen B, et al. Frequency of mutations in individuals with breast cancer referred for BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing using next-generation sequencing with a 25 gene panel. Cancer. 2015;121(1):25–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Susswein LR, Marshall ML, Nusbaum R, et al. Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variant prevalence among the first 10,000 patients referred for next-generation cancer panel testing. Genet Med. 2016;18(8):823–832. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium Cancer Risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1310–1316. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.15.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, et al. Prevalence and penetrance of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population series of 649 women with ovarian cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:700–710. doi: 10.1086/318787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson D, Easton DF. The breast cancer linkage consortium. Cancer incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1358–1365. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.18.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meijers-Heijboer H, van den Ouweland A, Klijn J, et al. Low-penetrance susceptibility to breast cancer due to CHEK2(*)1100delC in noncarriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Nat Genet. 2002;31(1):55–59. doi: 10.1038/ng879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasielewski M, den Bakker MA, van den Ouweland A, et al. CHEK2 1100delC and male breast cancer in the Netherlands. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116(2):397–400. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Syrjakoski K, Kuukasjarvi T, Auvinen A, Kallioniemi OP. CHEK2 1100delC is not a risk factor for male breast cancer population. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(3):475–476. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohayon T, Gal I, Baruch RG, Szabo C, Friedman E. CHEK2*1100delC and male breast cancer risk in Israel. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(3):479–480. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neuhausen S, Dunning A, Steele L, et al. Role of CHEK2*1100delC in unselected series of non-BRCA1/2 male breast cancers. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(3):477–478. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dufault MR, Betz B, Wappenschmidt B, et al. Limited relevance of the CHEK2 gene in hereditary breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2004;110(3):320–325. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Offit K, Pierce H, Kirchhoff T, et al. Frequency of CHEK2*1100delC in New York breast cancer cases and controls. BMC Med Genet. 2003;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falchetti M, Lupi R, Rizzolo P, et al. BRCA1/BRCA2 rearrangements and CHEK2 common mutations are infrequent in Italian male breast cancer cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110(1):161–167. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi DH, Cho DY, Lee MH, et al. The CHEK2 1100delC mutation is not present in Korean patients with breast cancer cases tested for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112(3):569–573. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9878-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans DG, Bulman M, Young K, et al. BRCA1/2 mutation analysis in male breast cancer families from North West England. Fam Cancer. 2008;7(2):113–117. doi: 10.1007/s10689-007-9153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding YC, Steele L, Kuan CJ, Greilac S, Neuhausen SL. Mutations in BRCA2 and PALB2 in male breast cancer cases from the United States. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126(3):771–778. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1195-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fackenthal JD, Marsh DJ, Richardson AL, et al. Male breast cancer in Cowden syndrome patients with germline PTEN mutations. J Med Genet. 2001;38(3):159–164. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.3.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sousa B, Moser E, Cardoso F. An update on male breast cancer and future directions for research and treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;717(1–3):71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song YN, Geng JS, Liu T, et al. Long CAG repeat sequence and protein expression of androgen receptor considered as prognostic indicators in male breast carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e52271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plon SE, Eccles DM, Easton D, et al. Sequence variant classification and reporting: recommendations for improving the interpretation of cancer susceptibility genetic test results. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(11):1282–1291. doi: 10.1002/humu.20880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pesaran T, Karam R, Huether R, et al. Beyond DNA: an integrated and functional approach for classifying germline variants in breast cancer genes. Int J Breast Cancer. 2016;2016:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2016/2469523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norquist BM, Harrell MI, Brady MF, et al. Inherited mutations in women with ovarian carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, et al. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Prostate Cancer (SEER 18 2009-2013). National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Accessed 9 Sept 2016

- 34.Casadei S, Norquist BM, Walsh T, et al. Contribution of inherited mutations in the BRCA2-interacting protein PALB2 to familial breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(6):2222–2229. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antoniou AC, Casadei S, Heikkinen T, et al. Breast-cancer risk in families with mutations in PALB2. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(6):497–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahman N, Seal S, Thompson D, et al. PALB2, which encodes a BRCA2-interacting protein, is a breast cancer susceptibility gene. Nat Genet. 2007;39(2):165–167. doi: 10.1038/ng1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanco A, de la Hoya M, Balmana J, et al. Detection of a large rearrangement in PALB2 in Spanish breast cancer families with male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(1):307–315. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1842-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LaDuca H, McFarland R, Gutierrez S et al (2016) Taming concerns regarding the accuracy of laboratory clinical data: a detailed comparative analysis. Abstract, American Society of Human Genetics: ACMG Abstract 741F

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.