Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer is a common cancer all over the world. Aberrations in the cell cycle checkpoints have been shown to be of prognostic significance in colorectal cancer.

Methods

The expression of cyclin D1, cyclin A, histone H3 and Ki-67 was examined in 60 colorectal cancer cases for co-regulation and impact on overall survival using immunohistochemistry, southern blot and in situ hybridization techniques. Immunoreactivity was evaluated semi quantitatively by determining the staining index of the studied proteins.

Results

There was a significant correlation between cyclin D1 gene amplification and protein overexpression (concordance = 63.6%) and between Ki-67 and the other studied proteins. The staining index for Ki-67, cyclin A and D1 was higher in large, poorly differentiated tumors. The staining index of cyclin D1 was significantly higher in cases with deeply invasive tumors and nodal metastasis. Overexpression of cyclin A and D1 and amplification of cyclin D1 were associated with reduced overall survival. Multivariate analysis shows that cyclin D1 and A are two independent prognostic factors in colorectal cancer patients.

Conclusions

Loss of cell cycle checkpoints control is common in colorectal cancer. Cyclin A and D1 are superior independent indicators of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Therefore, they may help in predicting the clinical outcome of those patients on an individual basis and could be considered important therapeutic targets.

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in Western countries [1]. In Egypt, CRC has unique characteristics that differ from that reported in other countries of the western society. It was estimated that 35.6% of the Egyptian CRC cases are below 40 years of age and patients usually present with advanced stage, high grade tumors that carry more mutations [2]. This uniquely high proportion of early-onset CRC, the early and continuous exposure to hazardous environmental agents, the different mutational spectrum and the prevalent consanguinity in Egypt justify further studies [3]. It was proved that most cancers result from accumulation of genetic alterations involving certain groups of genes, the majority of which are cell cycle regulators that either stimulate or inhibit cell cycle progression [1]. Cell proliferation allows orderly progression through the cell cycle, which is governed by a number of proteins including cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases [4,5]. The cyclins belong to a superfamily of genes whose products complex with various cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks) to regulate transitions through key checkpoints of the cell cycle [6]. Abnormalities of several cyclins have been reported in different tumor types, implicating, in particular, cyclin A, cyclin E and cyclin D [6,7].

Cyclin D1 is a G1 cyclin that regulates the transition from G1 to S phase since its peak level and maximum activity are reached during the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Whereas cyclin A is regarded a regulator of the transition to mitosis since it reaches its maximum level during the S and G2 phases [8]. The mechanisms likely to activate the oncogenic properties of the cyclins include chromosomal translocations, gene amplification and aberrant protein overexpression [7,9].

Several studies have shown that, histone H3 mRNA expression can be used to identify the S phase fraction (SPF) through the in situ hybridization (ISH) technique [10,11]. The level of histone H3 mRNA reaches its peak during the S phase and then drops rapidly at the G2 phase [12].

In face of the increasing incidence of CRC and its peculiar pattern in the Egyptian population, the present study was conducted to assess the role of Ki-67 (pan-cell cycle marker), cyclin D1 (G1 phase marker), histone H3 mRNA (S phase marker), cyclin A (S to G2 phase marker) in CRC. The expression level of these markers was correlated to the clinicopathologic features and the overall survival of patients.

Methods

Tissue samples

Paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were obtained from 60 CRC patients (47 colon and 13 rectal carcinomas) that were diagnosed and treated at the National Cancer Institute, Cairo, Egypt during the period from January, 1997 to June, 2002. Clinicopathological data of the studied cases are illustrated in table 1. None of the patients received any chemotherapy or irradiation prior to surgery. Histological diagnosis of all cases was done by 2 independent pathologists according to the WHO Histological Classification. Tumors were staged according to the TNM staging system [13]. The depth of tumor invasion was classified as invasion of the mucosa including muscularis mucosa (m), invasion of the submucosa (sm), or invasion beyond the submucosa [8]. Normal colonic tissues were obtained from autopsy specimens (n = 20) and were used as a control. The actual survival rate of the patients was calculated from the date of resection to the date of death.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features of patients in relation to the staining index (SI) of Ki-67, cyclin D1, cyclin A, histone H3

| SI (mean + SD) | |||||

| Variables | No. of cases | Ki-67 | Cyclin DI | Cyclin A | Histone H3 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 36 | 18.0 ± 6.4 | 6.7 ± 4.3 | 12.7 ± 5.7 | 10.7 ± 5.3 |

| Female | 24 | 20.1 ± 5.8 | 8.8 ± 8.4 | 10.0 ± 6.0 | 10.7 ± 5.4 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≥50 | 41 | 11.7 ± 6.0* | 5.6 ± 5.2 | 10.0 ± 5.3 | 6.0 ± 5.0* |

| <50 | 19 | 23.8 ± 5.6 | 7.7 ± 6.8 | 13.6 ± 5.7 | 22.0 ± 5.2 |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||||

| <5.0 | 33 | 12.2 ± 6.3* | 5.3 ± 3.8* | 11.5 ± 6.1* | 10.3 ± 4.9* |

| ≥5.0 | 27 | 30.1 ± 6.2 | 22.8 ± 7.2 | 28.6 ± 5.6 | 24.0 ± 5.6 |

| Histology | |||||

| Normal | 20 | 3.5 ± 2.0* | 0.6 ± 0.2* | 2.3 ± 1.1* | 2.2 ± 0.9 |

| Carcinoma | 60 | 30.3 ± 6.2 | 24.9 ± 6.3 | 27.2 ± 5.8 | 10.7 ± 5.3 |

| GI | 15 | 11.7 ± 6.2 | 6.6 ± 4.0 | 10.0 ± 5.4 | 11.4 ± 4.9 |

| GII | 21 | 11.8 ± 5.6 | 8.9 ± 3.6 | 12.3 ± 6.5 | 7.8 ± 5.4 |

| GIII | 24 | 30.0 ± 4.3 | 22.0 ± 8.1 | 27.0 ± 4.9 | 11.5 ± 5.4 |

| Lymph node | |||||

| Negative | 33 | 19.5 ± 7.0 | 5.4 ± 5.3* | 11.9 ± 6.5 | 12.3 ± 5.5 |

| Positive | 27 | 21.3 ± 4.9 | 20.6 ± 6.9 | 12.5 ± 5.0 | 14.2 ± 5.0 |

| Depth of invasion | |||||

| m, sm | 17 | 20.7 ± 6.7 | 3.1 ± 3.1* | 11.9 ± 7.2 | 10.4 ± 5.1 |

| beyond sm | 43 | 21.9 ± 6.2 | 12.4 ± 6.5 | 12.2 ± 5.6 | 10.7 ± 5.4 |

| Stage | |||||

| I | 6 | 20.6 ± 6.7 | 5.7 ± 6.9 | 24.2 ± 6.9 | 11.1 ± 5.3 |

| II | 27 | 20.8 ± 6.9 | 5.3 ± 4.3 | 24.6 ± 6.0 | 10.4 ± 5.7 |

| III | 12 | 22.0 ± 5.4 | 7.7 ± 6.0 | 27.1 ± 5.2 | 10.4 ± 4.9 |

| IV | 15 | 24.7 ± 6.1 | 11.3 ± 9.6 | 27.5 ± 5.5 | 12.3 ± 6.2 |

* p. value < 0.05 (significant)

Immunohistochemistry

Four micron sections of each normal and tumor specimen were cut onto positive-charged slides; air dried overnight, de-paraffinized in xylene, hydrated through a series of graded alcohol and washed in distilled water and 0.01 PBS (pH 7.4). Slides were then processed for IHC as described by Handa et al. [8]. using the following antibodies: Ki-67 (MIB-1, Dako), cyclin A (6E6; Novocastra, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, UK) and cyclin D1 (DCS-6, Dako). A case of invasive breast cancer was used as a positive control for Ki-67 and cyclin A whereas a case of mantle cell lymphoma was used as a control for cyclin D1. Negative controls were obtained by replacing the primary antibody by non-immunized rabbit or mouse serum.

Brown nuclear staining was regarded as a positive result for all studied markers. The proportion of positively-stained cells and the intensity of staining were scored in tumor and normal colorectal mucosal sections at medium power (×200). The degree of positive tumor staining (percentage of positive tumor cells in the examined section) was scored from 1–6 and the staining intensity was scored from 0–6 according to the pattern of staining in the examined section. Staining index (SI) was calculated by multiplying the cellularity and staining scores as described by King et al. [14].

In situ hybridization

All tumor samples and 5 normal controls were assessed for histone H3 mRNA by ISH using the commercially available 550 base fluorescein-labeled DNA probe (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) as described by Nagao et al., 1996. This probe hybridizes to the whole mRNA transcript of the human histoneH3 gene including the5' and 3' un-translated regions. Scoring of histone H3 mRNA was performed as for immunohistochemistry, however, hybridization signals were detected in the cytoplasm.

Molecular detection of cyclin D1 gene amplification

High molecular weight DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues of the tumor and normal colorectal mucosal samples as previously described [15]. The proportion of neoplastic and normal cells was determined in each tumor sample by examining hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides obtained from the edge of the specimen used for DNA extraction. Tumor samples were evaluated for amplification of cyclin D1 if more than 75% of the examined sections were formed of neoplastic cells. Accordingly, 50 cases were eligible for the analysis. Ten micrograms of the extracted DNA was digested with EcoR1. DNA from selected cases was also digested with BglII and HindIII. Samples were separated on 0.8% agarose gels and transferred to Hybond-N membranes (Amersham Int., Amersham, UK). The membranes were hybridized with 50% formamide, 5 × SSC, 5 × Denhardt's, 500 μg/ml denatured salmon sperm DNA, 10% dextran sulphate and 106 cpm/ml of 32P-labeled PRAD-1 probe for 24 h. Membranes were washed with 2 × SSC, 0.1% SDS at room temperature for 30 min followed by 2 × SSC, 0.1% SDS at 60°C for 30 min and 0.1 × SSC, 0.1% SDS at 60°C for 1 h. Filters were autoradiographed using an intensifying screen at -70°C for 24–72 h. After being stripped free of the PRAD-1 probe, the same blots were hybridized with 32P-labeled B-actin probe to normalize against possible variations in the loading or transfer of DNA. The autoradiograms were analyzed using a densitometer. Intensities of PRAD-1/cyclin D1 were normalized to the β-actin control bands. The degree of amplification was calculated from these normalized values. Amplification was considered when the signal of the tumor band was ≥2-fold the value of the matched normal mucosa [16].

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney non-parametric test was used to compare the SIs of pairs of subjects whereas the Kruskal-wallis was used for categorial data. Correlation between indices was performed using a simple linear regression test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to create survival curves which were analyzed by the log-rank test. The impact of different variables on survival was determined using the Cox proportional hazards model. p. values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

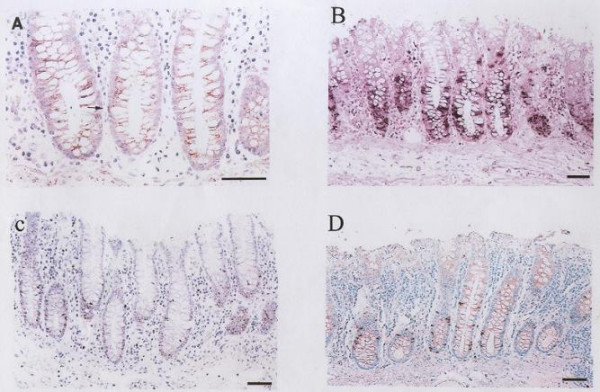

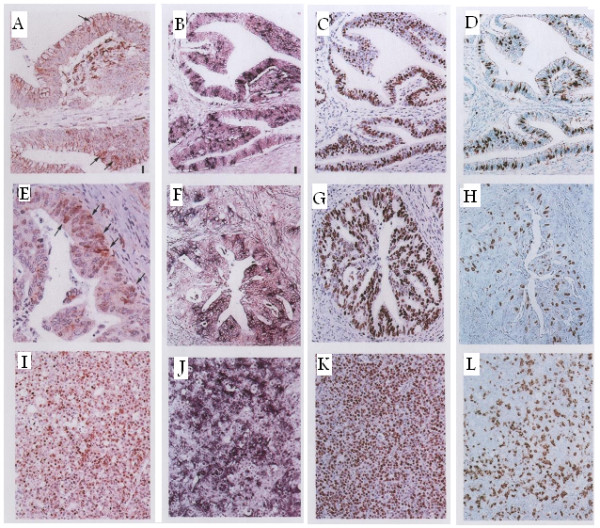

The results of IHC are illustrated in figures 1 and 2. In general, the staining index (SIs) of all studied markers was higher in carcinomas than in normal colonic mucosal samples (p = 0.0001). Normal colorectal mucosa revealed positive imunostaining for Ki-67 in the lower half of the crypts only. A heterogeneous staining pattern was detected in the neoplastic cells of well and moderately-differentiated adenocarcinomas whereas a diffuse homogeneous staining pattern was detected in poorly-differentiated carcinomas. The SI ranged from 10–40.2 (mean: 24.6 ± 6.5).

Figure 1.

Normal colonic mucosa showing positive nuclear immunostaining for: (a) cyclin D1, (b) ISH of histone H3 mRNA, (c) Ki-67 and (d) cyclin A

Figure 2.

A case of well differentiated adenocarcinoma with positive immunostaining for: (a) cyclin D1, (b) histone H3 mRNA, (c) Ki-67, and (d) cyclin A. Another case of moderately differentiated denocarcinoma with positive immunostaining for: (e) cyclin D1, (f) histone H3 mRNA, (g) Ki-67, and (h) cyclin A. A case of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with diffuse staining for: (i) cyclin D1, (j) ISH of histone H3 mRNA, (k) Ki-67 and (l) cyclin A.

Immunostaining for cyclin D1 was predominantly nuclear but cytoplasmic staining was detected in some cases. However, unless a nuclear staining was also detected, cases with cytoplasmic staining were considered negative. Normal colorectal mucosal samples were almost negative for cyclin D1 whereas 41 out of the 60 (68.3%) CRC cases were positive. Marked heterogeneity was observed in well- and moderately-differentiated adenocarcinomas even within the same tumor. Poorly-differentiated carcinomas revealed a diffuse staining pattern with more darkly-stained nuclei. The SI ranged from 0.5–28.6 (mean: 9.3 ± 4.2).

Positive nuclear staining for cyclin A was detected in 80% (48/60) of CRC cases and in all non-neoplastic control samples. Positively-stained nuclei were confined to the lower half of the crypts in normal colonic mucosa and diffusely-dispersed in carcinomas. The SI ranged from 3.3–30.2 (mean: 15.1 ± 6.6).

Histone H3 mRNA was intensely expressed in the cytoplasm of all examined samples either neoplastic or non-neoplastic. The distribution of histone H3 mRNA was similar to that of cyclin A and Ki-67 however, the proportion of histone H3 mRNA positive cells was less than that of Ki-67. The SI ranged from 1.8–24.2 (mean: 12.4 ± 5.3).

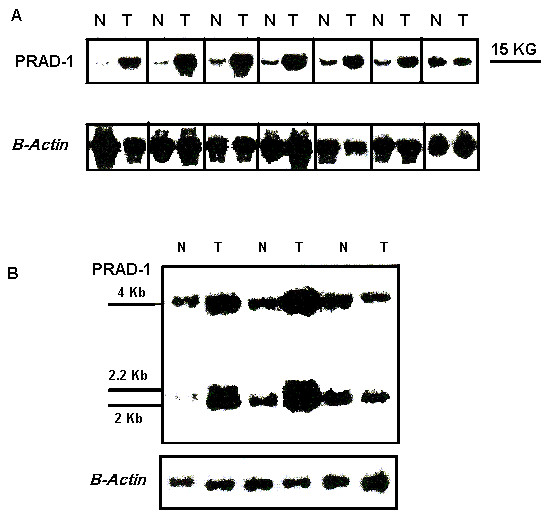

The PRAD-1 probe detected 3 EcoRI fragments of 4.0, 2.2 and 2.0 and 1 BglII fragment of 15 Kb. PRAD-1/cyclin D1 gene amplification was detected in 22/50 (44%) cases analyzed. The degree of amplification was heterogeneous with 2–10 fold increase when compared to normal mucosal samples (Figure 3). Amplification was confirmed by other restriction enzymes.

Figure 3.

A: Southern blot analysis of normal mucosa (N) and their seven corresponding cases of colonic adenocarcinomas (T1–T7), cases No. 1, 2, 4, and 5 are poorly differentiated whereas cases No. 3, 6, and 7 are moderately differentiated. Genomic DNA was digested with BglII, fractionated by electrophoresis in agarose gel, transferred onto membranes and hybridized with PRAD1 and β-actin. Tumors number 1–6 (Lanes 1–6) show different degrees of PRAD1/cyclin D1 amplification, tumor number 7 (lane 7) was not amplified. B: Southern blot analysis of 3 cases of adenocarcinomas (T) and matched normal colonic mucosa (N). Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI, fractionated by electrophoresis in agarose gel, transferred onto membranes and hybridized with PRAD1 and β-actin probes for loading control. The identification of the 3 tumors is the same as in Fig. 3A with amplification of PRAD1/cyclin D1 in tumors number 4, 5 (Lanes 1, 2) but not 7 (Lane 3).

Correlations

There was a significant correlation between cyclin D1 gene amplification and protein overexpression. Out of the 22 cases that showed amplification 14 showed protein overexpression (concordance = 63.6%).

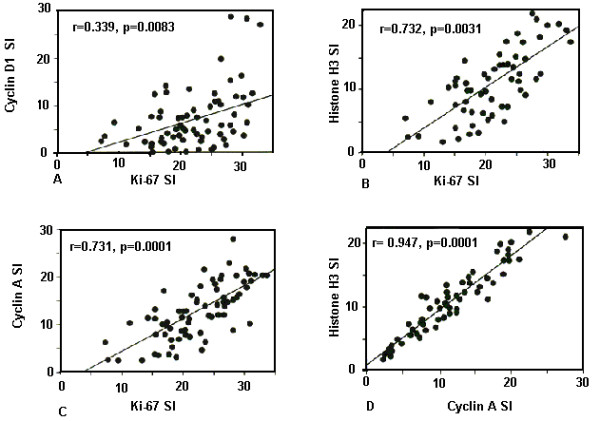

Linear regression analysis of SIs revealed a significant correlation between Ki-67 and cyclin D1, cyclin A, histone H3 as well as between the SIs of cyclin A and histone H3 (p = 0.008, 0.0001, and 0.0001 respectively) (Figure 4). There was a significant relationship between the SI of both Ki-67 and cyclin A and the degree of differentiation of tumors as well as the size of the tumor (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01 respectively). In addition, SI of Ki-67 and histone H3 were higher in patients <50 years than in those ≥50 years (p < 0.05) (table 1).

Figure 4.

Correlation between the staining intensity of (a) Ki-67 vs. cyclin D1, (b) Ki-67 vs. histone H3, (c) Ki-67 vs. cyclin A and (d) cyclin A vs. histone H3 mRNA expression.

In addition table 2 shows a significant relationship between high cyclin D1 SI and large, poorly-differentiated tumors, carcinomas with positive lymph node metastasis and deeply-invasive carcinomas (p < 0.05, p < 0.001, p < 0.05 and p < 0.05 respectively). Whereas cyclin D1 gene amplification was significantly associated with an advanced disease stage since amplification was detected in 10/15 (66.7%) of stage IV tumors compared to 12/45 (26.7%) of stage I-III tumors (p = 0.002). Similarly, DNA amplification was detected in 60.5% (26/43) of the carcinomas with extensive local invasion (beyond sm) but only in 23.5% (4/17) of the carcinomas with limited invasion (m, sm) (p = 0.001). A significant correlation was also present between cyclin D1 gene amplification and the presence of lymph node metastasis (p = 0.008) as well as between the SI of histone H3, the size of the tumor and the patient's age (p < 0.05, p < 0.001 respectively). The SI was higher in tumors >5 cm in diameter and in patients <50 years.

Table 2.

The relation between cyclin D1 overexpression vs cyclin D1 amplification and clinicopathological prognostic markers.

| Variables | No. of cases | Cyclin DI overexpression | Cyclin D1 Amplification |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| <5.0 | 33 | 5.3 ± 3.8* | 13/33 |

| ≥5.0 | 27 | 22.8 ± 7.2 p <0.05 | 9/27 p <0.236 |

| Histology | |||

| GI | 15 | 6.6 ± 4.0 | 7/15 |

| GII | 21 | 8.9 ± 3.6 | 8/21 |

| GIII | 24 | 22.0 ± 8.1 p <0.001 | 7/24 p <0.075 |

| Lymph node | |||

| Negative | 33 | 5.4 ± 5.3* | 6/33 (18.2%) |

| Positive | 27 | 20.6 ± 6.9 p <0.05 | 16/27 (59.3%) p <0.008 |

| Depth of invasion | |||

| m, sm | 17 | 3.1 ± 3.1* | 4/17 (23.5%) |

| beyond sm | 43 | 12.4 ± 6.5 p <0.05 | 26/43 (60.5%) p <0.001 |

| Stage | |||

| early | 45 | 5.5 ± 10.1 | 12/45 (26.7%) |

| late | 15 | 11.3 ± 9.6 P = 0.175 | 10/15 (66.7%) p <0.002 |

Survival analysis

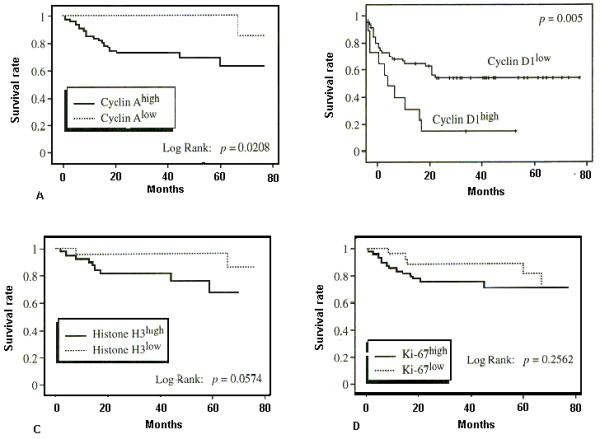

The mean follow-up period for all patients was 30 months (range: 1–66 months). Eighteen of 60 patients had already died by the time the study was completed. We defined the cutoff level for overexpression of each cell cycle marker at the point that showed the maximum difference of survival rate between the 2 groups separated by that point. Cox regression analysis revealed that cyclin A overexpression (our definition: SI ≥ 10.5), cyclin D1 overexpression (our definition: SI ≥ 6.1), poorly differentiated histology, lymph node metastasis, TNM stage, tumor size and depth of invasion were all significant prognostic variables for survival (Table 3). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the subgroups of patients who are subdivided according to each marker's status are shown in Figure 5. Patient with tumors that showed Ki-67 overexpression (our definition: SI ≥ 11.5) and histone H3 overexpression (our definition: SI ≥ 8.2) tended to have poor prognosis but this did not reach a statistically significant level, however the overall survival was significantly lower in patient with cyclin A and cyclin D1 overexpression. Cox multivariate regression analysis revealed that lymph node metastasis, cyclin A and cyclin D1 overexpression were independent negative prognostic factors after adjustment for the depth of tumor invasion, age and sex of the patient (Table 4).

Table 3.

Uunivariate analysis of the relationship between survival and the tested markers

| PredictiveVariables | Median Survival | HR | CI | P |

| Ki-67 | ||||

| <11.5 | 36 | |||

| ≥11.5 | 32 | 1.826 | 0.636 – 5.243 | 0.26 |

| Cyclin D1 | ||||

| <6.1 | 35 | |||

| ≥6.1 | 18 | 7.246 | 1.007 – 45.150 | 0.03* |

| Histone H3 | ||||

| <8.2 | 35 | |||

| ≥8.2 | 29 | 4.639 | 0.854 – 25.196 | 0.07 |

| Cyclin A | ||||

| <10.5 | 35 | |||

| ≥10.5 | 15 | 7.820 | 1.017 – 60.122 | 0.02* |

| Histological grade | ||||

| Low | 38 | |||

| High | 10 | 7.331 | 2.696 – 19.940 | 0.0001* |

| Lymph node | ||||

| Negative | 38 | |||

| Positive | 15 | 6.826 | 1.973 – 23.621 | 0.002* |

| Stage | ||||

| I, II, III | 38 | |||

| IV | 12 | 6.378 | 1.842 – 22.083 | 0.001* |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||

| <5.0 | 35 | |||

| ≥5.0 | 13 | 4.835 | 1.386 – 16.868 | 0.01* |

| Depth of invasion | ||||

| T1, T2 | 36 | |||

| T3, T4 | 20 | 7.759 | 1.024 – 58.789 | 0.04* |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <50 | 38 | |||

| ≥50 | 28 | 2.802 | 0.988 – 7.943 | 0.0526 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 38 | |||

| Female | 36 | 0.696 | 00.274 – 1.766 | 0.4449 |

* p. value < 0.05 (significant)

HR: Hazard Ratio

CI: 95% confidence Interval

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for colorectal carcinoma. Overall survival is significantly lower in patients with (a) cyclin A and (b) cyclin D1 overexpression. Patients with high SI for histone H3 mRNA have poorer prognosis but this was not statistically significant (c). No significant difference was present between patients with high Ki-67 SI and those with low Ki-67 SI (d).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis ofthe relationship between survival and thetested markers

| PredictiveVariables | HR | CI | P |

| Cyclin D1 | 10.864 | 1.055 – 86.250 | 0.03* |

| (baseline < 6.1) | - | - | - |

| Cyclin A | 13.886 | 1.012 – 190.579 | 0.0490* |

| (baseline < 10.5) | - | - | - |

| Positive Lymph node metastasis | 3.921 | 1.057 – 14.472 | 0.0410* |

| Stage IV | 3.411 | 1.048 – 12.083 | 0.03* |

| Depth of invasion | |||

| T3, T4 | 5.408 | 0.449 – 65.080 | 0.1836 |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≥50 | 1.996 | 0.678 – 5.878 | 0.2310 |

| Sex | 0.910 | 0.315 – 2.358 | 0.8453 |

p. value < 0.05 (significant)

HR: Hazard Ratio

CI: 95% confidence Interval

Discussion

The proliferative activity of CRC cells has been investigated in several studies either by immunohistochemical determination of cell proliferation index using antibodies to some types of cyclins or by flowcytometric determination of the SPF of the cell cycle [8]. Although Leach et al. [17] did not find cyclin D1 gene amplification in a panel of 47 CRC cell lines; its protein was overexpressed in about 30% of CRC cases that were included in the studies of Bartakova et al. [6] and Arber et al. [18]. In the former study [6]cyclin D1 was aberrantly accumulated in a significant subset of human CRC cases and the cell lines derived from these cases were dependent on cyclin in their cell cycle progression. In the second study [18], overexpression of cyclin D1 was detected in 30% of adenomatous polyps indicating that overexpression is a relatively early event in colon carcinogenesis which is possibly responsible for the pathological changes in the mucosa preceding neoplastic transformation. More recently, Holland et al. [19], Pasz-Walczak et al. [20] and Utsunomiya et al. [21] reported up-regulation of cyclin D1 in 58.7%, 100% and 43% of their studied cases respectively.

In the present study, up-regulation of cyclin D1 was detected in 68.3% of the cases. The SI was significantly higher in carcinomas than in normal colorectal mucosa and in poorly-differentiated adenocarcinomas it was approximately twice that of other histological types. Amplification and/or overexpression of cyclin D1 significantly correlated with deeply invasive tumors and positive lymph node metastasis. Our results in this regards are consistent with previous studies [8,22]. In 2001, Holland et al. [19]. demonstrated that deregulation of cyclin D1 and p21waf proteins are important in colorectal tumorigenesis and have implications for patient prognosis. Similarly McKay et al. [23] found that cyclin D1 was the only protein in their panel (cyclin D1, p53, p16, Rb-1, PCNA and p27) that correlated with improved outcome in CRC patients. However, few studies failed to detect any correlation between cyclin D1 overexpression and the clinicopathological factors in CRC [6,18]. This controversy in results could partially be explained by the difference in the sampling of studied cases. The present study included 24 cases of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, which is not common in other studies of CRC in western countries. This was possible because the majority of CRC cases diagnosed in Egypt are of high histological grade [3]. The correlation between cyclin D1 overexpression and the high histological grade was also reported in other tumor types including non-small cell lung carcinomas [24] and squamous cell carcinomas of the larynx [16]. Another possible explanation for the observed controversy in the results of different studies is the detection method used.

In the present work, overexpression of cyclin D1 was more common than gene amplification of the PRAD-1/cyclin D1 gene with a 63.6% concordance. This was similarly reported by Bartakova et al. [6] who mentioned that there is a subset of CRC cases in which cyclin D1 is overexpressed without PRAD-1/cyclin D1 gene amplification. Consistent with this hypothesis are reports of elevated cyclin D1 mRNA levels and immunohistochemically detectable accumulation of the protein in over one third of breast cancer cases at a frequency significantly higher than that deduced from DNA amplification studies [9,25]. These data imply that mechanisms other than gene amplification can also lead to deregulation and accumulation of cyclin D1 in solid tumors.

So far, several studies were done to reveal the prognostic significance of cyclin D1 overexpression in various carcinomas, including CRC [22]. However, these studies yielded conflicting results which could be attributed to organ heterogeneity. In our study, patients with tumors that exhibited cyclin D1 overexpression tended to have poor prognosis.

It was reported that, patients with cyclin A positive carcinomas had significantly shorter median survival times. Handa et al. [8] were able to detect cyclin A overexpression in 77% of their CRC cases. They also demonstrated that, cylcin A could be used as a prognostic factor of CRC. More recently, Habermann et al. [26] studied cases of ulcerative colitis with and without an associated adenocarcinoma for the presence of cyclin A overexpression. They found that, cyclin A overexpression was higher in cases of ulcerative colitis with adenocarcinomas than in those without adenocarcinomas. Consequently, they concluded that, cyclin A could be used for monitoring ulcerative colitis patients and for the early detection of an emerging carcinoma in this high risk group of patients.

In our study, cyclin A was detected in 80% of the patients and Cox regression analysis showed that it could be used as a prognostic marker in CRC in addition to cyclin D1.

It would have been useful if we assessed the expression level of cyclin A by another technique (DNA amplification). This would have added more information regarding the gene status on one hand and confirmed the results of IHC on the other hand. Unfortunately, this was not possible because in most of the cases included in the present work, the extracted DNA was not sufficient to study cyclin amplification after the assessment of cyclin D1.

In 1996, Nagao et al. [11] reported that histone H3 labeling index significantly correlated with ki-67 immunostaining and was high in poorly differentiated human hepatocellular carcinoma. This was similarly reported in the present work since we found a significant correlation between the SI of histone H3 and Ki-67. However, no statistically significant correlation was found between histone H3 SI and any of the studied clinicopathological factors.

Although Ki-67 immunostaining reflects the proliferative activity of CRC, it has not been recognized as a significant prognostic factor in this type of tumors [27,28]. However, Suzuki at al. [29] found a significant correlation between Ki-67 labeling index and local invasion of CRC. In the present study there was a significant relationship between the SI of Ki-67, tumor size and grade. However, Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed no significant difference in survival rates between patients with- and without overexpression of Ki-67.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that cyclin D1, cyclin A, histone H3 and Ki-67 are overexpressed in a subset of CRC, however only cyclin D1 and cyclin A overexpression correlates with poor differentiation and tumor progression. This indicates the superiority of cyclin A and cyclin D1 as indicators of poor prognosis compared to Ki-67 and histone H3 mRNA in CRC. Cyclin A and D1 could therefore be considered significant, independent prognostic factors in CRC patients. These findings are especially important in stage II patients since 25–30% of those patients have poor prognosis in spite of being node-negative. However, the standard clinicopathologic prognostic factors can not identify this subset accurately and therefore; there is a great demand for more accurate, individually-based, biological prognostic parameters that help in detecting this high risk group of patients who can benefit from an adjuvant therapy. If the findings of the present study are confirmed in a larger study, evaluation of cyclin A and D1 may be applicable to clinical management of CRC, allowing the identification of patients with poor prognosis.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

List of abbreviations

CRC – Colorectal cancer

OS – overall survival

SI – staining index

SPF – S phase fraction

ISH – in situ hybridization

m – muscularis mucosa

sm – invasion of the sub mucosa

Authors' contributions

BA and ZA-R carried out the molecular genetic studies, designed, coordinated the study and drafted the manuscript. BA and El-HS carried out all the histopathological and immunohistochemical studies. El-SA participated in molecular genetic studies and drafted the manuscript. MM coordinated the study. El-SM carried out all the patient clinical data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Abeer A Bahnassy, Email: chaya2000@hotmail.com.

Abdel-Rahman N Zekri, Email: ncizakri@starnet.com.eg.

Soumaya El-Houssini, Email: chaya2000@hotmail.com.

Amal MR El-Shehaby, Email: chaya2000@hotmail.com.

Moustafa Raafat Mahmoud, Email: ncizakri@starnet.com.eg.

Samira Abdallah, Email: chaya2000@hotmail.com.

Mostafa El-Serafi, Email: melserafi@starnet.com.eg.

References

- Jiang GL, Huang S. Adenovirus expressing RIZ1 in tumor suppressor gene therapy of microsatellite unstable colorectal cancers. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1796–1798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliman AS, Bondy ML, Levin B, Hamza MR, Ismail K, Ismail S, Hammam HM, El-Hattab O, Kamal SM, Soliman AG, Dorgham LA, McPherson RS, Beasley RP. Colorectal cancer in Egyptian patients under 40 years of age. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:26–30. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970328)71:1<26::AID-IJC6>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliman AS, Bondy ML, Guan Y, El-Badawy S, Mokhtar N, Bayomi S, Raouf AA, Ismail S, McPherson RS, Abdel-Hakim TF, Beasley PR, Levin B, Wei Q. Reduced expression of mismatch repair genes in colorectal cancer patients in Egypt. Int J Oncol. 1998;12:1315–1319. doi: 10.3892/ijo.12.6.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordon-Cardo C. Mutations of cell cycle regulators. Biological and clinical implications for human neoplasia. Am J pathol. 1995;147:545–560. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T, Pines J. Cyclins and cancer. II. Cyclin D and CDK inhibitors come of age. Cell. 1994;79:573–528. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkova J, Lukas J, Strauss M, Bartek J. The PRAD-1/cyclin D1 oncogene product accumulates aberrantly in a subset of CRCs. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:568–573. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motokura T, Arnold A. Cyclins and oncogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1155:63–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-419X(93)90022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa K, Yamakawa M, Takeda H, Kimura S, Takahashi T. Expression of the cell cycle markers in colorectal carcinoma: Superiority of cyclin A as an indicator of poor prognosis. Int J cancer. 1999;84:225–233. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990621)84:3<225::AID-IJC5>3.3.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillett C, Fantl V, Smith R, Fisher C, Bartek J, Dickson C, Barnes D, Peters G. Amplification and overexpression of cyclin D1 in breast cancer detected by immunohistochemical staining. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1812–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gown AM, Jiang JJ, Matles H, Skelly M, Goodpaster T, Cass L, Reshatof M, Spaulding D, Coltrera DM. Validation of the S-phase specificity of histone (H3) in situ hybridization in normal and malignant cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:221–226. doi: 10.1177/44.3.8648081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao T, Ishida Y, Kondo Y. Determination of S-phase cells by in situ hybridization for histone H3 mRNA in hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation with histological grade and other cell proliferative markers. Mod Pathol. 1996;9:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou MY, Chang AL, McBride J, Donoff B, Gallagher GT, Wong DT. A rapid method to determine proliferation patterns of normal and malignant tissues by H3 mRNA in situ hybridization. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:729–733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobin LH, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumors. 5. John Wiley, New York; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- King RJ, Coffer AI, Gilbert J, Lewis K, Nash R, Millis R, Raju S, Taylor RW. Histochemical studies with a monoclonal antibody raised against a partially purified soluble estradiol receptor preparation from human myometrium. Cancer Res. 1985;45:5728–5733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slebos RJ, Boerrigter L, Evers SG, Wisman P, Mooi WJ, Rodenhuis S. A rapid and simple procedure for the routine detection of ras point mutations in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Diag Moln Path. 1992;1:136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jares P, Fernandez P, Campo E, Nadal A, Bosch F, Aiza G, Nayach I, Traserra J, Cardesa A. PRAD-1/cyclin D1 gene amplification correlates with messenger RNA overexpression and tumor progression in human laryngeal carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4813–4817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach FS, Elledge SJ, Sherr CJ, Willson JK, Markowitz S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Amplification of cyclin genes in colorectal carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1986–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber N, Hibshoosh H, Moss SF, Sutter T, Zhang Y, Begg M, Wang S, Weinstein IB, Holt PR. Increased expression of cyclin D1 is an early event in multistage colorectal carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:669–674. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8608874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland TA, Elder J, McCloud JM, Hall C, Deakin M, Fryer AA, Elder JB, Hoban PR. Subcellular localization of cyclin D1 protein in colorectal tumors is associated with p21 (WAF1/CIP1) expression and correlates with patient survival. Int J Cancer. 2001;95:302–306. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010920)95:5<302::AID-IJC1052>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasz-Walczak G, Kordek R, faflik M. P21(WAF1) expression in colorectal cancer: correlation with p53 and cyclin D1 expression, clinicopathological parameters and prognosis. Pathol Res Pract. 2001;197:683–689. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsunomiya T, Doki Y, Takemoto H, Shiozaki H, Yano M, Sekimoto M, Tamura S, Yasuda T, Fujiwara Y, Monden M. Correlation of beta-catenin and cyclin D1 expression in colon cancers. Oncology. 2001;61:226–233. doi: 10.1159/000055379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Chung YS, Kang SM, Ogawa M, Onoda N, Nakata B, Nishiguchi Y, Ikehara T, Okuno M, Sowa M. Overexpression of cyclin D1 and p53 is associated with disease recurrence in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Int JCancer. 1997;74:310–315. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970620)74:3<310::AID-IJC13>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JA, Douglas JJ, Ross VG, Curran S, Loane JF, Ahmed FY, Cassidy J, McLeod HL, Murray GI. Analysis of key cell cycle checkpoint proteins in colorectal tumors. J Pathol. 2002;196:386–393. doi: 10.1002/path.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mate JL, Ariza A, Aracil C, Lopez D, Isamat M, Perez-Piteira J, Navas-Palacios JJ. Cyclin D1 overexpression in non-small cell lung carcinoma: correlation with Ki-67 labeling index and poor cytoplasmic differentiation. J Pathol. 1996;180:395–399. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199612)180:4<395::AID-PATH688>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley MF, Sweeney KJ, Hamilton JA, Sini RL, Manning DL, Nicholson RI, DeFazio A, Watts CK, Musgrove EA, Sutherland RL. Expression and amplification of cyclin genes in human breast cancer. Oncogene. 1993;8:2127–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habermann J, Lenander C, Roblick UJ, Kruger S, Ludwig D, Alaiya A, Freitag S, Dumbgen L, Bruch HP, Stange E, Salo S, Tryggvason K, Auer G, Schimmelpenning H. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal carcinoma: DNA profile, laminin-5 gamma 2 chain and cyclin A expression as early markers for risk assessment. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:751–758. doi: 10.1080/003655201300192021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Petras RE, Easley KA, Bauer TW, Tubbe RR, Fazio VW. Ki-67-determined growth fraction versus standard staging and grading parameters in colorectal carcinoma. A multivariate analysis. Cancer. 1992;70:2602–2609. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921201)70:11<2602::aid-cncr2820701106>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shain AA, Ro JY, Brown RW, Ordonez NG, Cleary KR, El-Naggar AK, Wilson P, Ayala AG. Assessment of Ki-67-derived tumor proliferative activity in colorectal adenocarcinomas. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Matsumoto K, Terabe M. Ki-67 antibody labeling index in colorectal carcinoma. J clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:317–320. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]