Introduction

We are pleased to present this supplemental issue of The Gerontologist dedicated to reporting on the 2014 data from Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS), the largest national survey to date focused on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) older adults. The articles in this issue explore a breadth of topics critical to understanding the challenges, strengths, and needs of a growing and underserved segment of the older adult population. This introduction to the supplement provides foundational information to frame the papers that follow. We begin by reviewing population-based findings regarding the size and health status of the LGBT older adult population. Next, we summarize the Health Equity Promotion Model (HEPM; Fredriksen-Goldsen, Simoni, et al., 2014), the conceptual framework that guides our study. We then briefly review some of the key methodological challenges that exist in conducting research in this hard-to-reach population. Next, we present an overview of study design and methods as well as the study’s primary substantive and content areas. Lastly, we provide an overview of the articles in this issue, which cut across three major themes: risk and protective factors and life course events associated with health and quality of life among LGBT older adults; heterogeneity and subgroup differences in LGBT health and aging; and processes and mechanisms underlying health and quality of life of LGBT older adults.

The landscape of gerontological research, practice, and policy is shifting as the U.S. older adult population becomes increasingly diverse, including by sexual orientation and gender identity and expression. By harmonizing available data across population-based studies (e.g., California Health Interview Survey, 2014; Gates & Newport, 2012; Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2014; Washington State Department of Health, 2014), we estimate that 2.4% of older adults in the United States currently self-identify as LGBT, accounting for 2.7 million adults aged 50 and older, including 1.1 million aged 65 and older. The population will increase dramatically over the next few decades given the significant aging of the population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014); by 2060 the number of adults aged 50 and older who self-identify as LGBT will likely more than double to over five million. Recent U.S. population-based data have also shown that many individuals who do not identify as a sexual or gender minority report same-sex sexual behavior or attraction. In one recent study, for example, while just more than 5% of Americans aged 18–44 self-identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, 12% had engaged in same-sex sexual behavior (men who had sex with men, and women who had sex with women), and 13% were sexually attracted to members of the same sex (Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016). Thus, the total number of older adults who self-identify as LGBT, have engaged in same-sex sexual behavior or romantic relationships, and/or are attracted to members of the same sex is estimated to increase to more than 20 million by 2060.

Although the numbers of sexual and gender minority older adults are growing rapidly, they remain a largely invisible and under-researched segment of the older adult population. The Institute of Medicine (2011) has identified sexual orientation and gender identity as key gaps in health disparities research, with LGBT older adults as an especially understudied population. Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), a set of 10-year national health improvement objectives, highlighted LGBT people for the first time as a health disparate population and outlined goals to improve their health, safety, and well-being. Aging with Pride: NHAS represents one step toward filling the research gap that lies at the intersection of sexual orientation and gender identity and aging.

Health Disparities of LGBT Older Adults

A primary goal of current national health objectives is to reduce health disparities and adverse health outcomes resulting from social, economic, and environmental conditions (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). In some of the first population-based studies of lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adult health, utilizing state-level data, we documented significant health disparities (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Barkan, Muraco, & Hoy-Ellis, 2013). More recently, using multi-year national population-based data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS, 2013-2014), we further investigated health disparities by sexual orientation, gender, and age. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults aged 50 and older, compared to heterosexuals of similar age, were more likely to report higher prevalence of disabling chronic conditions. They reported higher rates of 9 out of 12 chronic conditions, compared with heterosexual peers, including low back pain, neck pain, and weakened immune system; other disparities were elevated rates of stroke, heart attack, asthma, and arthritis as well as comorbidity of chronic health conditions for sexual minority older women, and angina pectoris and cancer for sexual minority older men (Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2016a). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults were also more likely to report poor general health, mental distress, disability (especially problems with vision, ambulation, and cognition), sleep problems, and smoking; sexual minority older women were more likely to report excessive drinking.

There are insufficient population-based data to assess health disparities in some subgroups of sexual and gender minority older adults, leaving community-based data as the best available evidence. For instance, robust national population-based data to assess the health and well-being of transgender older adults is not available. Utilizing community-based data, we found transgender older adults were at higher risk of poor health outcomes compared to nontransgender sexual minority older adults; they were more likely to experience poor general health, disability, and mental distress, which were associated with elevated rates of victimization, discrimination, and lack of access to responsive care (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Cook-Daniels, et al., 2014). Community-based data have also shown elevated risks of poor health among bisexual older adults when compared with lesbian and gay older adults, in part due to higher identity stigma and disadvantages in socioeconomic and other resources (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Shiu, Bryan, Goldsen, & Kim, 2016).

Other marginalized background characteristics and social positions, such as racial/ethnic minority status, are known to be linked to disparities in health (Williams & Mohammed, 2009), yet racial/ethnic minority LGBT older adults have rarely been the focus of research. In some of our early research we documented elevated health, social, and economic disparities among racial/ethnic minority LGBT populations; for example, we observed heightened risks of smoking, asthma, and disability among Hispanic lesbian and bisexual women compared to Hispanic heterosexual women (Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2011). When compared to non-Hispanic White sexual minority women, Hispanic bisexual women showed more frequent mental distress and Hispanic lesbians showed a higher rate of asthma. These findings highlight the importance of assessing subgroup differences to gain a more nuanced understanding of aging and health in these diverse communities and to generate effective ways to reduce health inequities among LGBT older adults, which if left unchecked will result in substantially rising healthcare costs as the population grows.

The Health Equity Promotion Model

Existing research shows that, while a health disparate population, many LGBT older adults manifest resilience and good health despite marginalization (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Shiu, Goldsen, & Emlet, 2015). Yet, to date much of the sexual minority research has been driven by stress-related mental health models, such as the Minority Stress Model (Meyer, 2003), which articulates ways in which stigma, discrimination, and hostility lead to chronic stress, in turn causing mental health problems and unhealthy coping behaviors. While deficit-driven models help explain poor health outcomes in LGBT populations, they are less suited to address the resources, good health, and well-being observed in these communities.

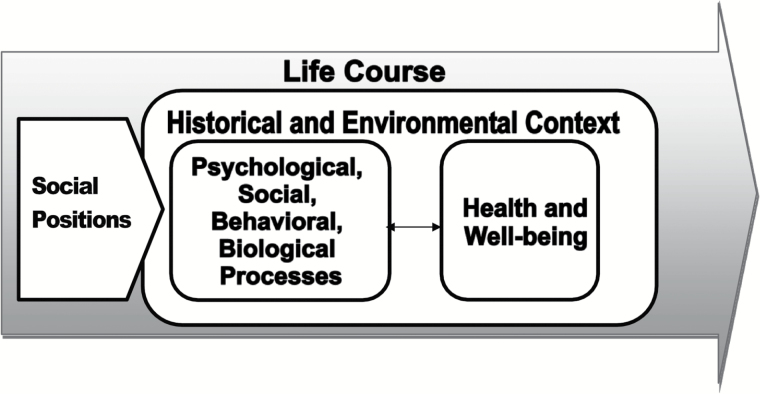

The Health Equity Promotion Model (HEPM) differs from previous models used to examine LGBT mental and physical health by incorporating a life course development perspective to understand the full range of contexts and experiences, both adverse and positive, that may influence individuals’ opportunities to achieve their full potential for good health and well-being. By identifying potential explanatory mechanisms that may predict changes in health and well-being over time, the model highlights both enduring characteristics (e.g., age cohort) and modifiable factors that may become targets for intervention (e.g., management of identity stigma and affirmation, health-promoting and risk behaviors, function and quality of social relations, and community norms); Figure 1 (for a full description of the model see Fredriksen-Goldsen, Simoni, et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

Health Equity Promotion Model.

As a life-course development framework, the model highlights the importance of understanding how historical (e.g., major historical as well as individual life events; Elder, 1994) and environmental factors (social, political, economic, physical, cultural environments; Halfon & Hochstein, 2002) influence health and well-being. Many LGBT older adults came of age when same-sex behavior and gender nonconformity were severely stigmatized and criminalized (Kane, 2003). The lives of LGBT individuals are influenced by such historical and environmental contexts, including stigma and changing cultural norms related to sexual orientation and gender identity and expression. See Appendix I for a glossary of terms.

By incorporating a developmental perspective, the HEPM highlights patterns across individual life trajectories as well as group-level variations in timing of historical and individual life events and adaptation to change (Boyd & Bee, 2012). For instance, experiences in earlier life stages may differ by generation. There are three generations of LGBT older adults currently living in the United States (Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2016b). The Invisible Generation, the oldest LGBT adults, who lived through the Great Depression and World War II, coming of age during a time when a pervasive silence prevailed with absence of public discourse related to sexual and gender minorities. Those of the Silenced Generation were inundated during their formative years with public anti-gay sentiment including a presidential order to fire gay and lesbian federal employees, the classification of homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and the television broadcast of the McCarthy hearings. The Pride Generation, by contrast, came of age during a time of significant social change reflected in the Stonewall riots, civil rights and women’s movements, the declassification of homosexuality as mental disorder, and the beginning of decriminalization of sodomy laws. Across all of these generations there were “rebel warriors” who resisted the social mores of the time and built their communities. Shared experiences by generations highlight the rapidly changing social and cultural norms related to both sexuality and gender, and illustrate the potential for individual and group-level differences in adaptation to such contexts, raising important generational issues for future study.

The HEPM suggests that intersecting background characteristics and social positions (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, and gender identity) are associated with the potential for synergistic disadvantage or advantage in health across the life course. Such characteristics and social positions may be associated with differing types of stressors as well as with strengths, resilience, and opportunities. LGBT communities are characterized by both intersectionality and heterogeneity of background characteristics and social positions. Particular subgroups within LGBT communities―for example, racial/ethnic minorities (Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2016), those with lower socioeconomic status (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2016), and those with stigmatizing health conditions (e.g., HIV/AIDS; Emlet, 2016)―may experience heightened social exclusion (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011), which can lead to further health deterioration as well as accelerated aging.

Health and well-being, as identified in the HEPM, are influenced by psychological, social, behavioral, and biological processes. For example, recent studies examing LGBT identity appraisal, an important psychological process, report relatively low levels of identity stigma among midlife adults, with positive evaluation of one’s identity as a potentially protective factor in health (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2015). The roles of social relationships in the well-being and aging of LGBT older adults have been widely documented (de Vries & Hoctel, 2006), including larger social networks and community engagement (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2015) as have the influences of health-promoting and risk behaviors (e.g., substance use, physical activities) on health-related quality of life (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2015). Incorporating biological processes, the model suggests that stressors may account for health disadvantages via overexposure to stressful psychosocial environments leading to physiological dysregulations (McEwen, 1998), which in turn may lead to cardiovascular disease, cancer, infection, cognitive decline, accelerated aging, and mortality (Juster, McEwen, & Lupien, 2010; Seeman, Singer, Rowe, Horwitz, & McEwen, 1997; Wolkowitz, Reus, & Mellon, 2011). Investigating the relationships among these processes and associated health outcomes provides the information necessary to develop and test community-based interventions to improve the health and well-being of at-risk LGBT older adults.

Challenges in Conducting LGBT Aging Research

In LGBT aging research, a primary concern is the ability to obtain a sample from a largely invisible and historically marginalized population of older adults. Most large public health and aging surveys have not included sexual orientation or gender identity questions, or have only asked them of younger age groups (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2015). The exclusion of older adults in sexuality and gender research rests on several assumptions, such as the questions would not be understood by older adults or would be too sensitive for them. However, these assumptions are not borne out by available evidence. In cognitive interviews (Redford & Van Wagenen, 2012), neither heterosexual nor nonheterosexual older adults found sexual orientation questions offensive or indicated that they would not answer them. We examined time-trends in one of the first population-based surveys to include a sexual orientation question; while adults aged 65 and older showed higher item nonresponse rates to sexual identity questions than younger adults, the item nonresponse rates have significantly decreased over time (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2015). In 2003, 2.4% responded “don’t know/not sure” and 4.1% refused to answer the sexual orientation question; by 2010 only 1.2% of older adults responded “don’t know/not sure” and 1.6% refused to answer. In 2013, when NHIS added a sexual orientation measure, less than 0.4% of respondents aged 65 and older responded “don’t know” and about 0.6% refused to answer. More recent analyses of NHIS para-data found that sexual minorities, compared to heterosexual respondents, showed higher contactability and lower reluctance to participate in the study (Lee, McClain, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, & Gurtekin, 2015).

Despite the growing visibility of LGBT older adults in population-based health surveys, they remain hard-to-reach. The population proportion of LGBT older adults is relatively low compared to some other demographic groups, rendering it both difficult and expensive to recruit LGBT older adults via probability sampling. Moreover, it is unfeasible to obtain sufficient samples of smaller subgroups of demographically diverse LGBT older adults using probability sampling, yet is crucial to better understand differences in aging and health-related needs by age cohort, gender, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity among LGBT older adults (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011). Previous studies have often collapsed sexual and gender minorities as a single group due to small sample size, underscoring the need for innovative recruitment approaches to reach these populations.

Because of the obstacles in obtaining sufficient population-based samples via probability sampling, LGBT health research has relied heavily on nonprobability sampling. Nonprobability sampling can be cost-effective and time-efficient but can produce biased results that lack generalizability to the larger population. Furthermore, most studies utilizing nonprobability sampling are geographically confined to a small area, yet differences in political, historical, cultural, and social contexts by geographic location may influence the health and well-being of LGBT older adults. Nationwide data collection is needed to examine the influence of contextual factors, including geographic location, on health and aging.

Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS)

In order to better understand health disparities, aging, and well-being by sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and age, the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Aging funded the first national longitudinal study of LGBT adults aged 50 and older in the United States: Aging with Pride: NHAS. The study aims, derived from the HEPM, include: (a) Foster a better understanding of health and well-being over time among LGBT older adults; (b) Investigate explanatory mechanisms of health equity and inequity, including risk and protective factors common to older adults as well as those distinct to LGBT individuals; and (c) Assess subgroup differences in health and explanatory factors, by age cohort, gender, and race/ethnicity, to identify those at highest risk. The papers in this supplement utilize 2014 survey data, in which we investigated risk and protective factors and life course events associated with health and quality of life among LGBT older adults, assessed subgroup differences, and examined the key roles of psychological, social, and behavioral mechanisms in the health and well-being of LGBT older adults. In future work, we will employ the longitudinal data to investigate changes in health and well-being over time and to assess temporal relationships between psychological, social, behavioral, and biological processes and health and well-being of LGBT older adults.

Recruiting a Hard to Reach Population

The sampling approach of Aging with Pride: NHAS was designed to achieve the study aims while taking into consideration the challenges in conducting research with LGBT older adults. Sampling goals in this study were to obtain a sample that reflects the heterogeneity of the population and minimizes noncoverage bias. To do so we set purposive sampling goals (targeted total sample size = 2,450) based on power analyses and projected attrition rates by age cohort, gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and geographic location. Individuals who self-identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender, or engaged in same-sex sexual behavior, or had a romantic relationship with, or attraction to, someone of the same sex or gender were included in the study. Age 50 or older was chosen as an inclusion criterion as consistent with most national longitudinal studies of older adult health, such as the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). There is evidence from multiple national probability surveys of “compression of morbidity” as a function of advantaged/resourced status (House, Lantz, & Herd, 2005), such that illness and functional limitations are “compressed” into older age among advantaged (e.g., high-SES) individuals, but occur linearly over the span of adulthood for less-advantaged individuals. Thus, when studying aging and health in systematically disadvantaged populations, it is important to follow them beginning in midlife to capture the full trajectory of age-related health changes. Throughout this supplement issue, we use the term “older adults” to refer to those aged 50 and older.

We used systematic recruitment procedures via community-based agency contact lists and social network clustering chain-referral. We utilized contact lists of 17 organizations serving older adults, selected based on geographic concentration of LGBT populations in general (Gates, 2015) as well as by race/ethnicity (Kastanis & Gates, 2013a, 2013b) from existing probability-based data ensuring coverage within each U.S. Census Division. The 17 community-based collaborators in the project were Center on Halstad (IL), The Fenway Institute: LGBT Aging Project (MA), FORGE Transgender Aging Network (WI), Gay & Lesbian Services Organization (KY), GLBT Generations (MN), GRIOT Circle (NY), The Health Initiative (GA), Los Angeles LGBT Center (CA), Mary’s House for Older Adults, Inc., (Washington, DC), Milwaukee LGBT Community Center (WI), Montrose Center (TX), Openhouse (CA), SAGE (NY), SAGE Metro St. Louis (MO), Senior Services (WA), Utah Pride Center (UT), and ZAMI NOBLA (GA). Via these collaborations, we obtained contact information from potential participants (n = 3,627) who were willing to participate in an ongoing study. Although participants were reached via contact lists of the community-based collaborators, they were not necessarily using services or programs of the agencies. Second, we used social network clustering chain-referral to further reduce noncoverage bias to meet the stratification sampling goals and access LGBT older adults not affiliated with community-based organizations. This approach has been used to recruit hard-to-reach populations with reciprocal connections within communities, and can be effective for accessing diverse social network clusters in underrepresented racial/ethnic minority communities (Walters, 2011). Two-hundred thirty-eight participants were recruited via the chain-referral method, increasing our sample’s demographic diversity by race/ethnicity, age, and gender.

Potential study participants were asked to complete a self-administered survey, available in English and Spanish, which was developed based on extensive pilot testing. The survey took approximately 40–60 minutes to complete, with an option for a mailed paper (55%) or online survey (45%); two reminder letters were sent as follow-up in one week intervals. Each participant received a $20 incentive for their time. In total, 2,686 participants completed a survey (response rate of 70%). We conducted random selection when the sample size of a particular subgroup exceeded the sampling goals. The final sample size for the longitudinal survey study was 2,450, with birth year ranging from 1916 to 1964, including 1,092 participants aged 50–64 (born 1950–1964) and 1,358 participants aged 65 and older (born 1949 or earlier). See Table 1 for unweighted sample characteristics. In addition to the survey data collection, 300 in-depth interviews were conducted to obtain life event inventories, physical, functional, and cognitive assessments, and biological measures using noninvasive dried blood spot (DBS) collection across four sites: Atlanta, Los Angeles, New York City, and Seattle metropolitan areas.

Table 1.

Unweighted and Weighted Demographic Characteristics of Study Sample Compared to Estimates from NHIS, HRS, and ACS

| Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults aged 50 and older | Adults aged 50 and older and living with same-sex partner | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age with Pride: NHAS (n = 2,450) | NHIS (n = 632) | Aging with Pride: NHAS (n = 778) | HRS (n = 140) | NHIS (n = 147) | ACS (n = 4,134) | |||

| Unweighted, % (n) | Weighted, % (SE) | Weighted, % (SE) | Unweighted, % (n) | Weighted, % (SE) | Weighted, % (SE) | Weighted, % (SE) | Weighted, % (SE) | |

| Sexual identity | ||||||||

| Lesbian or gay | 85.97 (2,102) | 72.26 (1.62) | 71.56 (2.56) | 95.37 (742) | 89.15 (1.99) | — | 85.23 (4.09) | — |

| Bisexual/other | 14.03 (343) | 27.74 (1.62) | 28.44 (2.56) | 4.63 (36) | 10.85 (1.99) | — | 14.77 (4.09) | — |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 41.74 (995) | 46.13 (1.69) | 48.79 (2.91) | 49.10 (382) | 51.05 (2.86) | 45.55 (2.32) | 58.47 (5.33) | 49.97 (2.26) |

| Male | 58.26 (1,389) | 53.87 (1.69) | 51.21 (2.91) | 50.90 (396) | 48.95 (2.86) | 54.45 (2.32) | 41.53 (5.33) | 50.03 (2.26) |

| Age group | ||||||||

| 50–64 | 44.53 (1,092) | 70.18 (1.35) | 74.93 (2.50) | 48.59 (378) | 72.79 (2.20) | 79.59 (3.83) | 84.12 (3.63) | 69.22 (1.68) |

| 65+ | 55.47 (1,358) | 29.82 (1.35) | 25.07 (2.50) | 51.41 (400) | 27.21 (2.20) | 20.41 (3.83) | 15.88 (3.63) | 30.78 (1.68) |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 81.96 (1,995) | 82.30 (1.33) | 87.16 (1.52) | 86.69 (671) | 88.20 (2.14) | 84.61 (3.51) | 96.20 (1.12) | 88.47 (0.91) |

| Black | 9.29 (226) | 9.59 (1.03) | 9.23 (1.28) | 6.85 (53) | 4.86 (1.49) | 4.96 (1.83) | 3.45 (1.08) | 5.42 (0.49) |

| Other | 8.75 (213) | 8.11 (0.97) | 3.50 (0.9) | 6.46 (50) | 6.94 (1.66) | 10.42 (3.08) | 0.34 (0.30) | 6.10 (0.78) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 6.91 (168) | 9.05 (1.04) | 9.27 (1.84) | 3.87 (30) | 7.27 (1.88) | 8.53 (2.76) | 10.40 (4.1) | 7.52 (0.58) |

Note: NHAS = National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study; ACS = American Community Survey; HRS = Health and Retirement Study; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey; SE = standard error.

Postsurvey Adjustment

To reduce bias arising from nonresponse and enhance the generalizability of the findings based on the Aging with Pride: NHAS nonprobability sample, we carried out postsurvey adjustment, which can be applied to nonprobability samples (Brick, 2011). This process projects the sample to the population using credible external population data and generates weights. Applying weights in the estimation equates to adjusting for the bias in the sample. Therefore, obtaining reliable data sources that represent the population of LGBT adults aged 50 and older is an important step in this process.

Because both sexual identity and same-sex partnership status are important indicators of sexual orientation, we employed three relevant probability-sampled external data sources to capture both indicators: NHIS, conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS, 2014); American Community Survey (ACS; Ruggles, Genadek, Goeken, Grover, & Sobek, 2015), conducted by the United States Census Bureau; and, the HRS (2012), conducted by the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research. NHIS is the largest nationwide health survey and has been used to characterize the lesbian, gay, and bisexual population based on self-reported sexual identity (Ward, Dahlhamer, Galinsky, & Joestl, 2014). We combined the 2013 and 2014 NHIS data (NCHS, 2014) in order to derive reliable estimates of the characteristics of self-identified sexual minority adults aged 50 and older. In addition, all three data sources (NHIS as well as ACS and HRS) contain household roster information including household members’ relationship status and gender, allowing for the identification of individuals in same-sex partnerships. The ACS has been widely used to characterize the population of U.S. adults in same-sex partnerships (Gates, 2015; Manning & Brown, 2015). The HRS, a nationally representative longitudinal study of adults aged 50 and older, provides well-established population estimates of older adults (Sonnega et al., 2014), including characteristics of the population by relationship status and living arrangement (Brown, Lee, & Bulanda, 2006).

Using these three well-established data sources, we parsed out the samples of lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons (identified in NHIS) and those in same-sex partnerships (identified in the three data sources), and used their characteristics as benchmarks to adjust the Aging with Pride: NHAS sample. The adjustment was conducted in two steps (Lee & Valliant, 2009). In the first step, we combined data in the Aging with Pride: NHAS sample and the self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual NHIS sample to predict the probability that each lesbian, gay, or bisexual person came from the probability (i.e., NHIS) versus nonprobability (i.e., Aging with Pride: NHAS) sample. In order to compute the probability, we used a logistic regression model with age, sex, sexual identity, Hispanic ethnicity, race, education, region, and house ownership as covariates. Utilizing the predicted probabilities as weights, the NHIS sample was used to adjust the Aging with Pride: NHAS sample with respect to the covariates in the model, as has been applied to other types of nonprobability samples (Lee, 2006).

The second step used a calibration method that takes into consideration population totals as benchmarks (Deville, Särndal, & Sautory, 1993). We divided the Aging with Pride: NHAS sample based on same-sex partnership status and applied calibration independently to the partnered and nonpartnered samples. For the partnered sample, all three external data sources were combined and used to obtain population totals needed for calibration, strengthening the resulting benchmarks. The population totals estimated from the respective data sources were combined through weighted averages, with the standard errors of the estimated totals as weights. Next, through calibration, the weights computed in the first step were further adjusted by controlling for age, race/ethnicity, gender, education, marital status, and region for both partnered and nonpartnered samples. When the resulting weights are applied, the Aging with Pride: NHAS sample resembles the samples from the external data sources with respect to these characteristics. After calibration, extreme weights were trimmed to increase precision following standard postsurvey weighting practices (e.g., Little, Lewitzky, Heeringa, Lepkowski, & Kessler, 1997; Potter, 1990). See Table 1 for weighted Aging with Pride: NHAS sample characteristics, and the characteristics across the three external probability samples.

Study Content Areas

Guided by the HEPM, extensive literature review, and our previous research, our multidisciplinary research team developed key study content areas and measures that were included in the survey and in-person interview instruments (Table 2). Whenever feasible, standardized measures utilized in other aging and health studies were used. Measures specific to the LGBT older adult population were developed, as needed, and evaluated via extensive testing to assess reliability and validity prior to inclusion in the longitudinal study battery of measures. See Appendix II for the measures developed and validated in the study. The key content areas are present below.

Table 2.

List of Study Content Areas

| Content area | Domains | Survey | In-person | Content area | Domains | Survey | In-person |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social positions | Sexual orientation (Sexual | √ | Informal Caregiving Social participation Community engagement* |

√ √ √ |

|||

| identity, attraction, and behavior; romantic relationship)* | |||||||

| Gender identity* | √ | Behavioral | Physical and wellness activities Tobacco use Alcohol and drug use Malnutrition Sleep Health care access Health care utilization Barriers to health care Relationship with health provider Health engagement/literacy* |

√ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ |

|||

| Gender expression* | √ | ||||||

| Age group | √ | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | √ | ||||||

| Socioeconomic status | √ | ||||||

| Social exclusion and inclusion | √ | ||||||

| Historical/ environmental |

Lifetime victimization and | √ | |||||

| discrimination* | |||||||

| Microaggressions* | √ | ||||||

| Day-to-day discrimination* | √ | ||||||

| Elder abuse | √ | ||||||

| Social and political climate on | √ | Biological | Cortisol Cholesterol Hemoglobin A1c C-reactive protein Blood pressure Waist circumference |

√ √ √ √ √ √ |

|||

| anti-discrimination | |||||||

| Normative/non-normative life events | √ | ||||||

| Psychological | Identity appraisal* | √ | |||||

| Identity management* | √ | ||||||

| Identity outness* | √ | Health and well-being | General health Chronic conditions Disability status Sexual problems Difficulties in ADL and IADL Physical functioning Cognitive functioning Depressive symptomatology Quality of life |

√ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ |

√ √ |

||

| Mastery Resilience* | √ | ||||||

| Perceived stress | √ | ||||||

| Spirituality* | √ | ||||||

| Social | Relationship status | √ | |||||

| Social network structure | √ | √ | |||||

| Social network function | √ | √ | |||||

| Social support | √ | √ | |||||

| Feeling of social isolation | √ |

Note. Asterisks indicate that corresponding measures are presented in Appendix II.

Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression, and Other Key Background Characteristics and Social Positions

To fully assess sexual orientation, Aging with Pride: NHAS measures four key components: sexual identity, sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and romantic relationships. We also measure key components of sex and gender, including sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and gender expression. Additional key background characteristics and social positions measured in this study include age, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic status based on income, financial assets, educational attainment, and employment status.

Historical and Environmental Factors

Aging with Pride: NHAS provides the opportunity to examine how historical and environmental contexts, such as structural stigma and social exclusion and inclusion, influence health problems or promote positive health and well-being of LGBT older adults. The study measures interpersonal and structural levels of stigma, discrimination and everyday forms of bias (Sue et al., 2007; Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997; Woodard et al., 2016) as well as anti-discrimination protections experienced by LGBT older adults. These measures include scales of lifetime victimization (e.g., verbal and physical threat and assault) and discrimination due to perceived sexual or gender identity (e.g., discrimination in workplace, housing); day-to-day discrimination (experiences of unfair treatment that may occur on a daily basis), LGBT microaggressions (experiences of micro-invalidation/insult, micro-assault, and hostile environment), and the enactment of anti-discrimination policies within differing geographic locations. The study also assesses normative and non-normative life events associated with health and quality of life, including those unique to LGBT older adults and those experienced by older adults in general.

Psychological Factors

Aging with Pride: NHAS investigates both positive and negative impacts of psychological factors on health and quality of life. The study includes assessments of LGBT-specific psychological factors including identity appraisal and management. Identity appraisal is measured by assessing identity stigma as well as identity affirmation. Identity stigma is “personal acceptance of sexual stigma as part of one’s value system and self-concept” (Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 2009), and identity affirmation is the extent to which an LGBT person has positive attitudes and feelings toward their sexual or gender identity (Mayfield, 2001; Mohr & Kendra, 2011). The measure of identity management assesses a series of decision-making processes that reflect a person’s efforts to strategically manage their sexual or gender identities in their social network and community (Anderson, Croteau, Chung, & DiStefano, 2001; Lance, Anderson, & Croteau, 2010). Assessments of other general psychological factors such as mastery, perceived resilience, spirituality, and perceived stress are also included in the study.

Social Factors

We assess multiple dimensions of an individual’s social resources and network: structure, quality, and function. Regarding structure, we measured partnership status, social network size and composition, and contact frequency with various types of social ties. In terms of quality of social network, we assess perceived social support and feeling of isolation. The functional property of the social network focuses on living arrangement, contact frequency with various types of social ties, and aspects of providing or receiving informal caregiving. We also include measures of general social participation (e.g., spiritual or religious activities, club meetings or group activities, and volunteering) as well as LGBT-specific community engagement including sense of belonging, participating in social activities and community activism, and contributing to the community (Frost & Meyer, 2012; Lin & Israel, 2012).

Behavioral Factors

Both health-promoting and risk behaviors are assessed in this study: moderate and vigorous physical activities and wellness leisure activities, sleep, and health risk behaviors including former and current tobacco use, alcohol and other drug use, and insufficient food intake. Aging with Pride: NHAS also measures health care utilization and access. Utilization of preventive care is measured via routine health checkup, flu shot, and blood pressure check. We assess whether LGBT older adults utilize aging services and health care services as needed and how LGBT older adults perceive the relationship with their health providers by, for example, asking how often health providers explain things in a way that is easy to understand and to what extent they are treated with respect in the healthcare setting. We also assess skills that LGBT older adults use to function in terms of health care access and utilization (e.g., accessing, understanding, and applying health information; and being proactive in one’s own care). Measures of health care access include health insurance coverage, usual source of care, and barriers to care.

Biological Factors

A series of biomarkers are used to measure allostatic load (AL), the wear and tear that the body experiences due to chronic stressors and health behaviors (McEwen, 1998). When stress is experienced over time, the human body is overexposed to multiple stress mediators, which have adverse effects on various organ systems, potentially leading to disease. Multiple stress mediators are interconnected and integration of multiple biomarkers can increase prediction of pathologies. In the current study we measure biological markers in relation to AL, including primary stress hormones (cortisol) and metabolic (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol, hemoglobin A1c), cardiovascular (blood pressure), immune (C-reactive protein), and anthropometric (waist circumference) parameters. The biomarker data are collected from in-person interview participants.

Health and Well-Being

Aging with Pride: NHAS includes a range of physical and mental health and well-being measures, utilizing both subjective and objective assessment tools. Physical health is evaluated with self-rated general health, physician-diagnosed chronic conditions, disability status, sexual problems, self-rated physical and cognitive functioning, and difficulties in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). In addition, objective assessments of physical and cognitive functioning are included in the in-person interview, such as handgrip strength and a brief screening tool for mild to severe cognitive impairment. Mental health-related measures include the assessment of depressive symptomatology, doctor-diagnosed depression and anxiety, and suicidal ideation. The study measures quality of life with a short version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire (Bonomi, Patrick, Bushnell, & Martin, 2000).

Papers in this Issue

The papers in this volume report on the findings from the 2014 wave of the study, cutting across three major themes. In the first paper Fredriksen-Goldsen and colleagues explore patterns in key life events among LGBT older adults and their association with health and well-being. This paper creates an important bridge to the second set of papers, which investigate the heterogeneity of LGBT older adults related to health, aging and well-being. Kim and colleagues examine health-promoting and risk factors that account for racial/ethnic disparities among LGBT older adults in health-related quality of life. Emlet and colleagues address HIV-related factors, adverse conditions and psychosocial characteristics that are associated with perceived resilience and mastery among gay and bisexual older men living with HIV infection. Next, Goldsen and colleagues examine the associations of legal marriage and relationship status with health-promoting and at-risk factors, health, and quality of life of LGBT older adults. Hoy-Ellis and colleagues explore relationships between the experience of prior military service, identity stigma, and mental health among transgender older adults. The final set of papers investigates processes and mechanisms of health equity and the quality of life of LGBT older adults. Fredriksen-Goldsen and colleagues test pathways accounting for positive health outcomes via lifetime marginalization, identity affirmation and management, social and psychological resources, and health behaviors. Kim and colleagues identify social network types among LGBT older adults and their relationship with mental health. Bryan and colleagues examine socioeconomic, psychological, behavioral, and social factors associated with high-risk drinking among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Lastly, Shiu and colleagues address the role of depression diagnosis and symptomatology in healthcare engagement among LGBT older adults.

Together these research articles consider the opportunities as well as the constraints in conducting research with hard-to-reach populations and the critical theoretical and methodological issues that surface when addressing the increasing sexual and gender diversity in our aging society. The papers develop a foundation of information necessary to guide the development of interventions and practice modalities that can be delivered within community-based agency settings to address the growing needs of LGBT older adults.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG026526 (K. I. Fredriksen-Goldsen, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

Online survey data were collected using REDCap electronic data capture tools (UL1TR000423 from NCRR/NIH). We also express our appreciation to Dr. Sunghee Lee for her contribution to the postsurvey adjustment for the study and Dr. Amanda E. B. Bryan for editorial support, assistance, and helpful feedback on earlier drafts of the manuscript. We want to extend our appreciation to the collaborating agencies and older adults who are participating in the study.

Appendix I

Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS) Definition of Terms

Asexual: A term that describes one who generally does not feel sexual attraction to any person.

Coming out: The process of recognizing and acknowledging one’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity to oneself and/or sharing it with others.

Gender expression: The expression of gender through behavior, appearance, mannerisms, and other such factors.

Gender identity: One’s true sense of self as a woman or a man, or both or neither, regardless of one’s assigned sex at birth.

LGBT: An abbreviation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender. Other letters designate additional identities, such as Q (queer and/or questioning); TS (two-spirit, traditionally used by some Native Americans to signify a continuum and fluidity of sexualities and genders); and SGL (same-gender loving, used primarily among African Americans to signify persons primarily attracted to people of their own sex or gender).

Queer: An umbrella term to describe people whose sexual orientation, gender identity and/or gender expression are fluid and/or do not fit into commonly used labels or categories.

Sex: Based on biological, anatomical, and genetic characteristics and indicators; typically assigned at birth, includes male, female, intersex. Intersex are persons born with genitals, organs, gonads, or chromosomes that are not clearly male or female, or both male and female.

Sexual identity: Identification of one’s sexuality.

Sexual orientation: Encompasses sexual identity, sexual behavior, attraction, and/or romantic relationships. For example, a person can identify one’s sexual orientation as lesbian, gay, bisexual, heterosexual/straight, or other, reflecting their romantic or sexual attractions. Someone may be attracted to members of one’s own sex or gender (gay or lesbian), or other sex or gender (heterosexual or straight) or both sexes or genders (bisexual). There may be incongruence between sexual identity, behavior, attraction, and/or romantic relationships. For example, one may identify as heterosexual but have sex with someone of the same sex or gender.

Transgender/Trans: Umbrella terms to describe people whose gender identities are not congruent with their sex assigned at birth. FTM denotes female-to-male; MTF denotes male-to-female. Cisgender is used to describe persons whose gender identities are congruent with their assigned sex at birth; persons who are not transgender.

Appendix II

Selected Measures Developed and Validated by Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS)

Sexual Orientation (Sexual Identity, Attraction, Sexual Behavior, Romantic Relationship)

Sexual identity

Q: Which of the following best represents how you CURRENTLY think of yourself?

(Response: Gay or lesbian; Bisexual; Straight or heterosexual; Not listed [please specify])

Attraction

Q: During the PAST 12 MONTHS, which of the following best describes your attractions?

(Response: Entirely to men; Mostly to men; Equally to women and men; Mostly to women; Entirely to women; No attractions; Not listed [please specify])

Sexual behavior

Q: During the PAST 12 MONTHS, about how many men have you had sex with, even if only one time?

(Response: ___Number of men)

Q: During the PAST 12 MONTHS, about how many women have you had sex with, even if only one time?

(Response: ___Number of women)

Romantic relationship

Q: During the PAST 12 MONTHS, have you had a romantic relationship with a woman?

(Response: Yes/No)

Q: During the PAST 12 MONTHS, have you had a romantic relationship with a man?

(Response: Yes/No)

Sex and Gender (Sex, Gender Identity, Gender Expression, Trans/Transgender)

Sex

Q: Which of the following best describes your assigned status at birth?

(Response: Female; Male; Intersex)

Gender identity

Q: Which of the following best represents how you CURRENTLY think of your gender?

(Response: Woman; Man; Not listed [please specify])

Trans/Transgender

Q: Do you consider yourself to be trans/transgender?

(Response: Yes/No)

Q: How old were you when you first considered yourself trans/transgender?

(Response: Age in years)

Gender expression

Q: Which best represents how you CURRENTLY express your gender, such as your behavior and mannerisms? Please check the box below that most closely matches how you express yourself.

(Visual analogue scale: feminine–masculine)

Historical/Environmental Factors

Lifetime victimization (α = .85)

Q: Please indicate how many times IN YOUR LIFE you have experienced each of the following events because you are, or were thought to be LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender).

-

1)

I was verbally insulted (yelled at, criticized).

-

2)

I was threatened with physical violence.

-

3)

I had an object thrown at me.

-

4)

I was punched, kicked, or beaten.

-

5)

I was threatened with a knife, gun or another weapon.

-

6)

I was attacked sexually.

-

7)

Someone threatened to tell someone else I am lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender.

-

8)

My property was damaged or destroyed.

-

9)

I was hassled by the police.

(Response: Never, Once, Twice, three or more times)

Lifetime discrimination (α = .77)

Q: Please indicate how many times IN YOUR LIFE you have experienced each of the following events because you are, or were thought to be, LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender).

-

1)

I was not hired for a job.

-

2)

I was not given a job promotion.

-

3)

I was fired from a job.

-

4)

I was prevented from living in the neighborhood I wanted.

-

5)

I was denied or provided inferior care such as healthcare.

(Response: Never, Once, Twice, three or more times)

Microaggressions (α = .85)

Q: In the PAST 12 MONTHS, how often have you experienced the following)?

-

1)

You experience media portraying LGBT stereotypes.

-

2)

In the place you live you experience people working against LGBT rights.

-

3)

People use derogatory terms to refer to LGBT individuals in your presence.

-

4)

People refer to sexual orientation or gender identity as a “lifestyle choice.”

-

5)

People say they understand you since they have LGBT friends.

-

6)

People make offensive remarks or jokes about LGBT individuals in your presence.

-

7)

People say or imply that LGBT individuals don’t have families.

-

8)

People say to you that they are tired of hearing about the “homosexual, gay or transgender agenda.”

(Response: Never; Less than once a year; A few times a year; A few times a month; At least once a week; Almost every day)

Day-to-day discrimination (α = .91)

Q: In your day-to-day life, how often do any of the following things happen to you?

-

1)

People do things that devalue and humiliate you.

-

2)

People suggest you are inferior to others.

-

3)

You experience an unfriendly or hostile environment.

-

4)

You are treated with less courtesy or respect than other people.

-

5)

You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores.

-

6)

People act as if they think you are not smart.

(Response: Never; Less than once a year; A few times a year; A few times a month; At least once a week; Almost every day). Respondents also indicate which of their identities is the reason they experienced day-to-day discrimination (sexual orientation, gender, transgender identity, ancestry or national origin, race, age, gender expression, religion, physical difficulties, mental difficulties, physical appearance, financial status, not listed [please specify]).

Psychological factors

Identity appraisal including Identity stigma (IS; α = .83), Identity affirmation (IA; α = .81)

Q: The following statements deal with emotions and thoughts related to being LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender). Indicate to what extent you agree or disagree with the following statements.

-

1)

I am proud to be LGBT. (IA)

-

2)

Being LGBT is as natural as being heterosexual or nontransgender. (IA)

-

3)

I feel ashamed of myself for being LGBT. (IS)

-

4)

I feel that being LGBT is a personal shortcoming for me. (IS)

-

5)

I wish I weren’t LGBT. (IS)

-

6)

I believe that being LGBT is as fulfilling as being heterosexual or nontransgender. (IA)

-

7)

I feel comfortable being LGBT. (IA)

-

8)

I feel that being LGBT is embarrassing. (IS)

(Response: Strongly disagree; Disagree; Slightly disagree; Slightly agree; Agree; Strongly agree)

Identity management (α = .79)

Q: As an LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender) person, indicate to what extent you agree or disagree with the following statements.

-

1)

I am open about my sexual orientation or gender identity whenever it comes up.

-

2)

When people assume that I’m not LGBT, I correct them.

-

3)

I try to tell other people my sexual orientation or gender identity.

-

4)

I disclose my sexual orientation or gender identity in indirect ways.

-

5)

I let others know of my interest in LGBT issues without identifying myself.

-

6)

I avoid things that may make others suspect my sexual orientation or gender identity.

-

7)

I make things up to hide my sexual orientation or gender identity.

-

8)

I make comments to give the impression that I am not LGBT.

-

9)

I display objects (magazines, symbols) that suggest my sexual orientation or gender identity.

(Response: Strongly disagree; Disagree; Slightly disagree; Slightly agree; Agree; Strongly agree)

Identity outness

Q: Please indicate your level of visibility with respect to being LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender). For example, if you have never told anyone about your sexual orientation or gender identity, circle “1”; if you have told everyone you know about your sexual orientation or gender identity, circle “10.”

Resilience (Adapted from Smith et al., 2008; α =.81)

Q: Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each of the following.

-

1)

I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times.

-

2)

It is hard for me to snap back when something bad happens.

-

3)

I usually come through difficult times with little trouble.

(Response: Strongly disagree; Disagree; Slightly disagree; Slightly agree; Agree; Strongly agree)

Spirituality (Adapted from Fetzer Institute, 2003; α = .92)

Q: How much do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements?

-

1)

I believe in a higher power or God who watches over me.

-

2)

The events in my life unfold according to a greater or divine plan.

-

3)

I try hard to carry my spiritual or religious beliefs into all my other dealings in life.

-

4)

I find strength and comfort in my spiritual or religious beliefs.

(Response: Strongly disagree; Disagree; Slightly disagree; Slightly agree; Agree; Strongly agree)

Social Resources

Community engagement (α = .86)

Q: Think about the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender) community. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each of the following.

-

1)

I help other people in the community.

-

2)

I get help from the community.

-

3)

I am active or socialize in the community.

-

4)

I feel part of the community.

(Response: Strongly disagree; Disagree; Slightly disagree; Slightly agree; Agree; Strongly agree)

Behavioral Factors

Health engagement/literacy (α = .89)

Q: The following statements are about health information. Please indicate how difficult or easy it is for you to.....

-

1)

Find information on health issues that concern you, such as health screenings, certain illnesses, or treatments.

-

2)

Understand what your doctor says to you.

-

3)

Judge the quality of information about health and illness from different sources.

-

4)

Use information from your doctor to make decisions about your health problems.

-

5)

Get the information you need when seeing a doctor.

-

6)

Request a second opinion about your health from a healthcare professional.

-

7)

Ask family or friends for help to understand health information.

-

8)

Make sure you find the right place to get the healthcare you need.

(Response: Very Difficult; Difficult; Easy; Very Easy)

References

- Anderson M. Z. Croteau J. M. Chung Y. B., & DiStefano T. M (2001). Developing an assessment of sexual identity management for lesbian and gay workers. Journal of Career Assessment, 9, 243–260. doi:10.1177/106907270100900303 [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi A. E. Patrick D. L. Bushnell D. M., & Martin M (2000). Validation of the United States’ version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) instrument. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53, 1–12. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00123-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd D. R., & Bee H. L (2012). Lifespan development (6th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Brick J. M. (2011). The future of survey sampling. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75, 872–888. doi:10.1093/poq/nfr045 [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. L. Lee G. R., & Bulanda J. R (2006). Cohabitation among older adults: A national portrait. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, S71–S79. doi:10.1093/geronb/61.2.S71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey. (2014). CHIS Adult Public Use File. [Data file]. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Copen C. E. Chandra A., & Febo-Vazquez I (2016). Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual orientation among adults aged 18–44 in the United States: Data from the 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports, 88, 1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deville J.-C. Särndal C.-.E., & Sautory O (1993). Generalized raking procedures in survey sampling. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88, 1013–1020. doi:10.1080/01621459.1993.10476369 [Google Scholar]

- de Vries B., & Hoctel P (2006). The family-friends of older gay men and lesbians. In Teunis N., Herdt G. (Eds.), Sexual inequalities and social justice (pp. 213–232). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. H. (1994). Time, human agency, and social-change—Perspectives on the life-course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 4–15. doi:10.2307/2786971 [Google Scholar]

- Emlet C. A. (2016). Social, economic, and health disparities among LGBT older adults. Generations, 40, 16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute. (2003). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Kalamazoo, MI: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I. (2016. a). Equity: A powerful force for the future of aging. 2016 Elder Friendly Futures Conference, Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I. (2016. b). The future of LGBT+ aging: A blueprint for action in services, policies, and research. Generations, 40, 6–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I. Cook-Daniels L. Kim H.-J. Erosheva E. A. Emlet C. A. Hoy-Ellis C. P., … Muraco A (2014). Physical and mental health of transgender older adults: An at-risk and underserved population. The Gerontologist, 54, 488–500. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I. Kim H.-J. Barkan S. E. Muraco A., & Hoy-Ellis C. P (2013). Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 1802–1809. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I. Kim H.-J. Emlet C. A. Muraco A. Erosheva E. A. Hoy-Ellis C. P., … Petry H (2011). The Aging and Health Report: Disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Seattle, WA: Institute for Multigenerational Health. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I., & Kim H.-J (2015). Count me in: Response to sexual orientation measures among older adults. Research on Aging, 37, 464–480. doi:10.1177/0164027514542109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I. Kim H.-J. Shiu C. S. Goldsen J., & Emlet C. A (2015). Successful aging among LGBT older adults: Physical and mental health-related quality of life by age group. Gerontologist, 55, 154–168. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I. Shiu C. Bryan A. E. B. Goldsen J., & Kim H.-J (2016). Health equity and aging of bisexual older adults: Pathways of risk and resilience. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I. Simoni J. M. Kim H.-J. Lehavot K. Walters K. L. Yang J., … Muraco A (2014). The Health Equity Promotion Model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 653–663. doi:10.1037/ort0000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost D. M., & Meyer I. H (2012). Measuring community connectedness among diverse sexual minority populations. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 36–49. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.565427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. J. (2015). Comparing LGBT rankings by metro area: 1990 to 2014. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. J., & Newport F (2012). Special report: 3.4% of US adults identify as LGBT. Politics. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/158066/special-report-adults-identify-lgbt.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Halfon N., & Hochstein M (2002). Life course health development: An integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. The Milbank Quarterly, 80, 433–479. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Retirement Study (2012). Public use dataset. Produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740). Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. M. Gillis J. R., & Cogan J. C (2009). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 32–43. doi:10.1037/a0014672 [Google Scholar]

- House J. S. Lantz P. M., & Herd P (2005). Continuity and change in the social stratification of aging and health over the life course: Evidence from a nationally representative longitudinal study from 1986 to 2001/2002 (Americans’ Changing Lives Study). The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, 15–26. doi:10.1093/geronb/60.Special_Issue_2.S15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juster R. P. McEwen B. S., & Lupien S. J (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 2–16. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane M. D. (2003). Social movement policy success: Decriminalizing state sodomy laws, 1969–1998. Mobilization: An International Journal, 8, 313–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kastanis A., & Gates G. J (2013. a). LGBT African-American individuals and African-American same-sex couples. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- Kastanis A., & Gates G. J (2013. b). LGBT Latino/a individuals and Latino/a same-sex couples. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-J., & Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I (2011). Hispanic lesbians and bisexual women at heightened risk for health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 102, e9–e15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-J., & Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I (2016). Disparities in mental health quality of life between Hispanic and non-Hispanic White LGB midlife and older adults and the influence of lifetime discrimination, social connectedness, socioeconomic status, and perceived stress. Research on Aging. doi:10.1177/0164027516650003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lance T. S. Anderson M. Z., & Croteau J. M (2010). Improving measurement of workplace sexual identity management. Career Development Quarterly, 59, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. (2006). Propensity score adjustment as a weighting scheme for volunteer panel web surveys. Journal of Official Statistics, 22, 329–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. McClain C. Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I. Kim H.-J., & Gurtekin T. S (2015). Examining sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and interview language as correlates of nonresponse using paradata. Presented at 2015 Annual Meeting of American Association for Public Opinion Research, Hollywood, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., & Valliant R (2009). Estimation for volunteer panel web surveys using propensity score adjustment and calibration adjustment. Sociological Methods & Research, 37, 319–343. doi:10.1177/0049124108329643 [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. J., & Israel T (2012). Development and validation of a psychological sense of LGBT Community Scale. Journal of Community Psychology, 40, 573–587. doi:10.1002/Jcop.21483 [Google Scholar]

- Little R. J. A. Lewitzky S. Heeringa S. Lepkowski J., & Kessler R.C (1997). Assessment of weighting methodology of the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Epidemiology, 146, 439–449. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning W. D., & Brown S. L (2015). Aging cohabiting couples and family policy: Different-sex and same-sex couples. Public Policy & Aging Report, 25, 94–97. doi:10.1093/ppar/prv012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health. (2014). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance data [Data file]. MA. [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield W. (2001). The development of an internalized homonegativity inventory for gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 41, 53–76. doi:10.1300/J082v41n02_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840, 33–44. doi:10.1111/j.1749–6632.1998.tb09546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr J. J., & Kendra M. S (2011). Revision and extension of a multidimensional measure of sexual minority identity: The Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 234–245. doi:10.1037/A0022858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (2014). National Health Interview Survey, 2013 and 2014 (machine-readable data file and documentation). Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Potter F. (1990). A study of procedures to identify and trim extreme sampling weights. Proceedings of the Section on Survey Research Methods, American Statistical Association, 1990, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Redford J., & Van Wagenen A (2012). Measuring sexual orientation identity and gender identity in a self-administered survey: Results from cognitive research with older adults. Paper presented at the Population Association of America: 2012 Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA: Retrieved from http://paa2012.princeton.edu/abstracts/122975 [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S. Genadek K. Goeken R. Grover J., & Sobek M (2015). Integrated public use microdata series: Version 6.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T. E. Singer B. H. Rowe J. W. Horwitz R. I., & McEwen B. S (1997). Price of adaptation—Allostatic load and its health consequences. MacArthur studies of successful aging. Archives of Internal Medicine, 157, 2259–2268. doi:10.1001/archinte.1997.00440400111013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. W., Dalen J., Wiggins K., Tooley E., Christopher P., & Bernard J (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15, 194–200.doi:10.1090/10705500802222972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnega A. Faul J. Ofstedal M. B. Langa K. M. Phillips J. F., & Weir D (2014). Cohort profile: The Health and Retirement Study (HRS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43, 576–585. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue D. W. Capodilupo C. M. Torino G. C. Bucceri J. M. Holder A. M. Nadal K. L., & Esquilin M (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62, 271–286. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2014). 2014 National Population Projections: Summary tables Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2012). Healthy People 2020 objectives Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default.aspx

- Walters K. L. (2011). Predicting CBPR success: Lessons learned from the HONOR Project. Hilton Head, SC: American Academy of Health Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Ward B. W. Dahlhamer J. M. Galinsky A. M., & Joestl S. S (2014). Sexual orientation and health among U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2013. National Health Statistics Reports, 77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington State Department of Health. (2014). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance data [Data file]. WA [Google Scholar]

- Williams D., & Mohammed S (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 20–47. doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Yu Y., Jackson J. S., & Anderson N. B (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 335–351.doi:10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkowitz O. M. Reus V. I., & Mellon S. H (2011). Of sound mind and body: depression, disease, and accelerated aging. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13, 25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford M. R., Chonody J. M., Kulick A., Brennan D. J., & Renn K (2015). The LGBQ microaggressions on campus scale: A scale development and validation study. Journal of Homosexuality, 62, 1660–1687. doi:10.1080/00918369.2015. 1078205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]