The American Diabetes Association’s (ADA’s) Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes is updated and published annually in a supplement to the January issue of Diabetes Care. The ADA’s Professional Practice Committee, comprised of physicians, diabetes educators, registered dietitians, and public health experts, develops the Standards. Formerly called Clinical Practice Recommendations, the Standards includes the most current evidence-based recommendations for diagnosing and treating adults and children with all forms of diabetes. ADA’s grading system uses A, B, C, or E to show the evidence level that supports each recommendation.

A—Clear evidence from well-conducted, generalizable randomized controlled trials that are adequately powered

B—Supportive evidence from well-conducted cohort studies

C—Supportive evidence from poorly controlled or uncontrolled studies

E—Expert consensus or clinical experience

This is an abridged version of the current Standards containing the evidence-based recommendations most pertinent to primary care. The tables and figures have been renumbered from the original document to match this version. The complete 2017 Standards of Care document, including all supporting references, is available at professional.diabetes.org/standards.

PROMOTING HEALTH AND REDUCING DISPARITIES IN POPULATIONS

Recommendations

Treatment plans should align with the Chronic Care Model, emphasizing productive interactions between a prepared proactive practice team and an informed activated patient. A

When feasible, care systems should support team-based care, community involvement, patient registries, and decision support tools to meet patient needs. B

Diabetes and Population Health

Clinical practice guidelines are key to improving population health; however, for optimal outcomes, diabetes care must be individualized for each patient. Thus, efforts to improve population health will require a combination of systems-level and patient-level approaches. With such an integrated approach in mind, the ADA highlights the importance of patient-centered care, defined as care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.

Care Delivery Systems

Despite the many advances in diabetes care, 33–49% of patients still do not meet targets for glycemic, blood pressure, or cholesterol control, and only 14% meet targets for all three measures while also avoiding smoking. Certain segments of the population, such as young adults and patients with complex comorbidities, financial or other social hardships, and/or limited English proficiency, face particular challenges to care. Even after adjusting for these factors, the persistent variability in the quality of diabetes care across providers and practice settings indicates that substantial system-level improvements are still needed.

Chronic Care Model

Numerous interventions to improve adherence to the recommended standards have been implemented. However, a major barrier to optimal care is a delivery system that is often fragmented, lacks clinical information capabilities, duplicates services, and is poorly designed for the coordinated delivery of chronic care. The Chronic Care Model (CCM) takes these factors into consideration and is an effective framework for improving the quality of diabetes care.

Six Core Elements

The CCM includes six core elements to optimize the care of patients with chronic disease:

Delivery system design (moving from a reactive to a proactive care delivery system where planned visits are coordinated through a team-based approach)

Self-management support

Decision support (basing care on evidence-based, effective care guidelines)

Clinical information systems (using registries that can provide patient-specific and population-based support to the care team)

Community resources and policies (identifying or developing resources to support healthy lifestyles)

Health systems (to create a quality-oriented culture)

Redefining the roles of the health care delivery team and empowering patient self-management are funda-mental to the successful implementation of the CCM. Collaborative, multidisciplinary teams are best suited to provide care for people with chronic conditions such as diabetes and to facilitate patients’ self-management.

Strategies for System-Level Improvement

Optimal diabetes management requires an organized, systematic approach and the involvement of a coordinated team of dedicated health care professionals working in an environment where patient-centered, high-quality care is a priority. Three objectives to achieve this include:

Optimizing provider and team behavior

Supporting patient self-manage-ment

Changing the care system

Tailoring Treatment to Reduce Disparities

Social determinants of health can be defined as the economic, environmental, political, and social conditions in which people live and are responsible for a major part of health inequality worldwide. Given the tremendous burden that obesity, unhealthy eating, physical inactivity, and smoking place on the health of patients with diabetes, efforts are needed to address and change the societal determinants of these problems.

Recommendations

Providers should assess social context, including potential food insecurity, housing stability, and financial barriers, and apply that information to treatment decisions. A

Patients should be referred to local community resources when available. B

Patients should be provided with self-management support from lay health coaches, navigators, or community health workers when available. A

CLASSIFICATION AND DIAGNOSIS OF DIABETES

Diabetes can be classified into the following general categories:

Type 1 diabetes (due to autoimmune β-cell destruction, usually leading to absolute insulin deficiency)

Type 2 diabetes (due to a progressive loss of β-cell insulin secretion frequently on the background of insulin resistance)

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) (diabetes diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not clearly overt diabetes prior to gestation)

Other specific types, including monogenic forms of diabetes

Diagnostic Tests for Diabetes

Diabetes may be diagnosed based on plasma glucose criteria—either the fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or the 2-h plasma glucose value after a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) —or A1C (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Criteria for the Diagnosis of Diabetes

| FPG ≥126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L). Fasting is defined as no caloric intake for at least 8 h.* |

| OR |

| 2-h plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) during an OGTT. The test should be performed as described by the World Health Organization, using a glucose load containing the equivalent of 75 g anhydrous glucose dissolved in water.* |

| OR |

| A1C ≥6.5% (48 mmol/mol). The test should be performed in a laboratory using a method that is NGSP certified and standardized to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial assay.* |

| OR |

| In a patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis, a random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L). |

In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia, results should be confirmed by repeat testing.

The same tests are used to screen for and diagnose diabetes and to detect individuals with prediabetes (Table 2). Prediabetes is defined as FPG of 100–125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/L); 2-h OGTT of 140–199 mg/dL (7.8–11.0 mmol/L); or A1C of 5.7–6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol).

TABLE 2.

Criteria for Testing for Diabetes or Prediabetes in Asymptomatic Adults

|

Type 2 Diabetes and Prediabetes

Recommendations

Screening to assess prediabetes and risk for future diabetes with an informal assessment of risk factors or validated tools should be considered in asymptomatic adults. B

To test for prediabetes, FPG, OGTT, and A1C are equally appropriate. B

Testing for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes should be considered in children and adolescents who are overweight or obese and who have two or more additional risk factors for diabetes. E

The American Diabetes Association Risk Test is an additional option for screening.

COMPREHENSIVE MEDICAL EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT OF COMORBIDITIES

The comprehensive medical evaluation includes the initial and ongoing evaluations, assessment of complications, management of comorbid conditions, and engagement of the patient throughout the process. People with diabetes should receive health care from a team that may include physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, dietitians, exercise specialists, pharmacists, dentists, podiatrists, and mental health professionals. Individuals with diabetes must assume an active role in their care. The patient, family, physician, and health care team should formulate the management plan, which includes lifestyle management.

Lifestyle management and psychosocial care are the cornerstones of diabetes management. Patients should be referred for diabetes self-management education (DSME), diabetes self-management support (DSMS), medical nutrition therapy (MNT), and psychosocial/emotional health concerns if indicated. Additional referrals should be arranged as necessary (Table 3). Patients should receive recommended preventive care services (e.g., immunizations and cancer screening); smoking cessation counseling; and ophthalmological, dental, and podiatric referrals. Clinicians should ensure that individuals with diabetes are appropriately screened for complications and comorbidities.

TABLE 3.

Referrals for Initial Care Management

|

Comprehensive Medical Evaluation

The components of the comprehensive diabetes medical evaluation are listed in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Components of the Comprehensive Diabetes Medical Evaluation*

Medical history

|

Physical examination

|

Laboratory evaluation

|

The comprehensive medical evaluation should all ideally be done on the initial visit, but if time is limited different components can be done as appropriate on follow-up visits.

Refer to the ADA position statement “Psychochsocial Care for People With Diabetes” for additional details on diabetes-specific screening measures.

Recommendations

A complete medical evaluation should be performed at the initial visit to

Confirm the diagnosis and classify diabetes. B

Detect diabetes complications and potential comorbid conditions. E

Review previous treatment and risk factor control in patients with established diabetes. E

Begin patient engagement in the formulation of a care management plan. B

Develop a plan for continuing care. B

Immunization

Recommendations

Provide routine vaccinations for children and adults with diabetes according to age-related recommendations. C

Annual vaccination against influenza is recommended for all people with diabetes ≥6 months of age. C

Vaccination against pneumonia is recommended for all people with diabetes who are 2–64 years of age with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). At age ≥65 years, administer the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) at least 1 year after vaccination with PPSV23, followed by another dose of vaccine PPSV23 at least 1 year after PCV13 and at least 5 years after the last dose of PPSV23. C

Administer three-dose series of hepatitis B vaccine to unvaccinated adults with diabetes who are aged 19–59 years. C

Consider administering three-dose series of hepatitis B vaccine to unvaccinated adults with diabetes who are ≥60 years of age. C

Comorbidities

Besides assessing diabetes-related complications, clinicians and their patients need to be aware of common comorbidities that affect people with diabetes and may complicate management.

Autoimmune Diseases

Recommendations

Consider screening patients with type 1 diabetes for autoimmune thyroid disease and celiac disease soon after diagnosis. E

Cancer

Diabetes is associated with increased risk of cancers of the liver, pancreas, endometrium, colon/rectum, breast, and bladder. The association may result from shared risk factors between diabetes and cancer (older age, obesity, and physical inactivity) or diabetes-related factors such as underlying disease physiology or diabetes treatments, although evidence for these links is scarce. Patients with diabetes should be encouraged to undergo recommended age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings and to reduce their modifiable cancer risk factors (obesity, physical inactivity, and smoking).

Cognitive Impairment/Dementia

Diabetes is associated with a significantly increased risk and rate of cognitive decline and an increased risk of dementia. In a 15-year prospective study of community-dwelling people >60 years of age, the presence of diabetes at baseline significantly increased the age- and sex-adjusted incidence of all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia compared with rates in those with normal glucose tolerance.

Fatty Liver Disease

Elevations of hepatic transaminase concentrations are associated with higher BMI, waist circumference, and triglyceride levels and lower HDL cholesterol levels. In a prospective analysis, diabetes was significantly associated with incident nonalcoholic chronic liver disease and with hepatocellular carcinoma. Interventions that improve metabolic abnormalities in patients with diabetes (weight loss, glycemic control, and treatment with specific drugs for hyperglycemia or dyslipidemia) are also beneficial for fatty liver disease.

Fractures

Age-specific hip fracture risk is significantly increased in people with both type 1 (relative risk 6.3) and type 2 (relative risk 1.7) diabetes in both sexes. Type 1 diabetes is associated with osteoporosis, but in type 2 diabetes, an increased risk of hip fracture is seen despite higher bone mineral density.

Hearing Impairment

Hearing impairment, both in high-frequency and low- to mid-frequency ranges, is more common in people with diabetes than in those without, perhaps due to neuropathy and/or vascular disease.

Low Testosterone in Men

Mean levels of testosterone are lower in men with diabetes compared with age-matched men without diabetes, but obesity is a major confounder. Treatment in asymptomatic men is controversial. The evidence that testosterone replacement affects outcomes is mixed, and recent guidelines do not recommend testing or treating men without symptoms.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Age-adjusted rates of obstructive sleep apnea, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), are significantly higher (4- to 10-fold) with obesity, and especially with central obesity. The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the population with type 2 diabetes may be as high as 23%, and the prevalence of any sleep disordered breathing may be as high as 58%.

Periodontal Disease

Periodontal disease is more severe and may be more prevalent in people with diabetes than in those without. Current evidence suggests that periodontal disease adversely affects diabetes outcomes, although evidence for treatment benefits on diabetes control remains unclear.

Psychosocial Disorders

Prevalence of clinically significant psychopathology in people with diabetes ranges across diagnostic categories, and some diagnoses are considerably more common in people with diabetes than for those without the disease. Symptoms, both clinical and subclinical, that interfere with a person’s ability to carry out diabetes self-management must be addressed. Diabetes distress is very common and distinct from a psychological disorder.

Anxiety Disorders

Recommendations

Consider screening for anxiety in people exhibiting anxiety or worries regarding diabetes complications, insulin injections or infusion, taking medications, and/or hypoglycemia that interfere with self-management behaviors and those who express fear, dread, or irrational thoughts and/or show anxiety symptoms such as avoidance behaviors, excessive repetitive behaviors, or social withdrawal. Refer for treatment if anxiety is present. B

People with hypoglycemic unawareness, which can co-occur with fear of hypoglycemia, should be treated using Blood Glucose Awareness Training (or another similar evidence-based intervention) to help re-establish awareness of hypoglycemia and reduce fear of hyperglycemia. A

Depression

Recommendations

Providers should consider annual screening of all patients with diabetes, especially those with a self-reported history of depression, for depressive symptoms with age-appropriate depression screening measures, recognizing that further evaluation will be necessary for individuals who have a positive screen. B

Beginning at diagnosis of complications or when there are significant changes in medical status, consider assessment for depression. B

Referrals for treatment of depression should be made to mental health providers with experience using cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, or other evidence-based treatment approaches in conjunction with collaborative care with the patient’s diabetes treatment team. A

Disordered Eating Behavior

Recommendations

Providers should consider reevaluating the treatment regimen of people with diabetes who present with symptoms of disordered eating behavior, an eating disorder, or disrupted patterns of eating. B

Consider screening for disordered or disrupted eating using validated screening measures when hyperglycemia and weight loss are unexplained based on self-reported behaviors related to medication dosing, meal plan, and physical activity. In addition, a review of the medical regimen is recommended to identify potential treatment-related effects on hunger/caloric intake. B

Serious Mental Illness

Recommendations

Annually screen people who are prescribed atypical antipsychotic medications for prediabetes or diabetes. B

Incorporate monitoring of diabetes self-care activities into treatment goals in people with diabetes and serious mental illness. B

LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT

Lifestyle management is a fundamental aspect of diabetes care and includes DSME and DSMS, nutrition, physical activity, smoking cessation, and psychosocial care.

DSME and DSMS

Recommendations

In accordance with the national standards for DSME and DSMS, all people with diabetes should participate in DSME to facilitate the knowledge, skills, and ability necessary for diabetes self-care and in DSMS to assist with implementing and sustaining skills and behaviors needed for ongoing self-management, both at diagnosis and as needed thereafter. B

Effective self-management and improved clinical outcomes, health status, and quality of life are key goals of DSME and DSMS that should be measured and monitored as part of routine care. C

DSME and DSMS should be patient-centered, respectful, and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and should help guide clinical decisions. A

DSME and DSMS programs have the necessary elements in their curricula to delay or prevent the development of type 2 diabetes. DSME and DSMS programs should therefore be able to tailor their content when prevention of diabetes is the desired goal. B

Because DSME and DSMS can improve outcomes and reduce costs B, DSME and DSMS should be adequately reimbursed by third-party payers. E

The overall objectives of DSME and DSMS are to support informed decision-making, self-care behaviors, problem-solving, and active collaboration with the health care team to improve clinical outcomes, health status, and quality of life in a cost-effective manner.

Four critical time points have been defined when the need for DSME and DSMS should be evaluated by the medical care provider and/or multidisciplinary team, with referrals made as needed:

At diagnosis

Annually for assessment of education, nutrition, and emotional needs

When new complicating factors (health conditions, physical limitations, emotional factors, or basic living needs) arise that influence self-management

When transitions in care occur

Nutrition Therapy

For many individuals with diabetes, the most challenging part of the treatment plan is determining what to eat and following a food plan. There is not a one-size-fits-all eating pattern for individuals with diabetes. The Mediterranean diet, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, and plant-based diets are all examples of healthful eating patterns. See Table 5 for specific nutrition recommendations.

TABLE 5.

MNT Recommendations

| Topic | Recommendations | Evidence Rating |

| Effectiveness of nutrition therapy | • An individualized MNT program, preferably provided by a registered dietitian, is recommended for all people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. | A |

| • For people with type 1 diabetes and those with type 2 diabetes who are prescribed a flexible insulin therapy program, education on how to use carbohydrate counting and, in some cases, fat and protein gram estimation to determine mealtime insulin dosing can improve glycemic control. | A | |

| • For individuals whose daily insulin dosing is fixed, having a consistent pattern of carbohydrate intake with respect to time and amount can result in improved glycemic control and a reduced risk of hypoglycemia. | B | |

| • A simple and effective approach to glycemia and weight management emphasizing portion control and healthy food choices may be more helpful for those with type 2 diabetes who are not taking insulin, who have limited health literacy or numeracy, or who are elderly and prone to hypoglycemia. | B | |

| • Because diabetes nutrition therapy can result in cost savings B and improved outcomes (e.g., A1C reduction) A, MNT should be adequately reimbursed by insurance and other payers. E | B, A, E | |

| Energy balance | • Modest weight loss achievable by the combination of reduction of caloric intake and lifestyle modification benefits overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes and also those with prediabetes. Intervention programs to facilitate this process are recommended. | A |

| Eating patterns and macronutrient distribution | • Because there is no single ideal dietary distribution of calories among carbohydrates, fats, and proteins for people with diabetes, macronutrient distribution should be individualized while keeping total caloric and metabolic goals in mind. | E |

| • A variety of eating patterns are acceptable for the management of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes including the Mediterranean diet, DASH, and plant-based diets. | B | |

| • Carbohydrate intake from whole grains, vegetables, fruits, legumes, and dairy products, with an emphasis on foods higher in fiber and lower in glycemic load, should be advised over other sources, especially those containing sugars. | B | |

| • People with diabetes and those at risk should avoid sugar-sweetened beverages to control weight and reduce their risk for CVD and fatty liver disease B and should minimize their consumption of foods with added sugar that have the capacity to displace healthier, more nutrient-dense food choices. A | B, A | |

| Protein | • In individuals with type 2 diabetes, ingested protein appears to increase insulin response without increasing plasma glucose concentrations. Therefore, carbohydrate sources high in protein should not be used to treat or prevent hypoglycemia. | B |

| Dietary fat | • Whereas data on the ideal total dietary fat content for people with diabetes are inconclusive, an eating plan emphasizing elements of a Mediterranean-style diet rich in monounsaturated fats may improve glucose metabolism and lower CVD risk and can be an effective alternative to a diet low in total fat but relatively high in carbohydrates. | B |

| • Eating foods rich in long-chain ω-3 fatty acids, such as fatty fish (EPA and DHA) and nuts and seeds (ALA) is recommended to prevent or treat CVD B; however, evidence does not support a beneficial role for ω-3 dietary supplements. A | B, A | |

| Micronutrients and herbal supplements | • There is no clear evidence that dietary supplementation with vitamins, minerals, herbs, or spices can improve outcomes in people with diabetes who do not have underlying deficiencies, and there may be safety concerns regarding the long-term use of antioxidant supplements such as vitamins E and C and carotene. | C |

| Alcohol | • Adults with diabetes who drink alcohol should do so in moderation (no more than one drink per day for adult women and no more than two drinks per day for adult men). | C |

| • Alcohol consumption may place people with diabetes at increased risk for hypoglycemia, especially if they are taking insulin or insulin secretagogues. Education and awareness regarding the recognition and management of delayed hypoglycemia are warranted. | B | |

| Sodium | • As for the general population, people with diabetes should limit sodium consumption to <2,300 mg/day, although further restriction may be indicated for those with both diabetes and hypertension. | B |

| Nonnutritive Sweeteners | • The use of nonnutritive sweeteners has the potential to reduce overall caloric and carbohydrate intake if substituted for caloric sweeteners and without compensation by intake of additional calories from other food sources. Nonnutritive sweeteners are generally safe to use within the defined acceptable daily intake levels. | B |

In overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes, modest weight loss, defined as sustained reduction of 5% of initial body weight, has been shown to improve glycemic control and to reduce the need for glucose-lowering medications. However, sustaining weight loss can be challenging. Weight loss can be attained with lifestyle programs that achieve a 500–750 kcal/day energy deficit or provide ∼1,200–1,500 kcal/day for women and 1,500–1,800 kcal/day for men, adjusted for the individual’s baseline body weight.

Physical Activity

Recommendations

Children and adolescents with type 1 or type 2 diabetes or prediabetes should engage in 60 min/day or more of moderate or vigorous intensity aerobic activity, with vigorous, muscle-strengthening, and bone-strengthening activities included at least 3 days/week. C

Most adults with with type 1 C or type 2 B diabetes should engage in 150 min or more of moderate-to-vigorous intensity activity per week, spread over at least 3 days/week, with no more than 2 consecutive days without activity. Shorter durations (minimum 75 min/week) of vigorous-intensity or interval training may be sufficient for younger and more physically fit individuals.

Adults with type 1 C or type 2 B diabetes should engage in 2−3 sessions/week of resistance exercise on nonconsecutive days.

All adults, and particularly those with type 2 diabetes, should decrease the amount of time spent in daily sedentary behavior. B Prolonged sitting should be interrupted every 30 min for blood glucose benefits, particularly in adults with type 2 diabetes. C

Flexibility training and balance training are recommended 2−3 times/week for older adults with diabetes. Yoga and tai chi may be included based on individual preferences to increase flexibility, muscular strength, and balance. C

Exercise in the Presence of Specific Long-Term Complications of Diabetes

Retinopathy

If proliferative diabetic retinopathy or severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy is present, then vigorous-intensity aerobic or resistance exercise may be contraindicated because of the risk of triggering vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment. Consultation with an ophthalmologist prior to engaging in an intense exercise regimen may be appropriate.

Peripheral Neuropathy

Decreased pain sensation and a higher pain threshold in the extremities result in an increased risk of skin breakdown, infection, and Charcot joint destruction with some forms of exercise. Therefore, a thorough assessment should be done to ensure that neuropathy does not alter kinesthetic or proprioceptive sensation during physical activity, particularly in those with more severe neuropathy.

Smoking Cessation: Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

Recommendations

Advise all patients not to use cigarettes and other tobacco products A or e-cigarettes. E

Include smoking cessation counseling and other forms of treatment as a routine component of diabetes care. B

Psychosocial Issues

Recommendations

Psychosocial care should be integrated with a collaborative, patient-centered approach and provided to all people with diabetes, with the goals of optimizing health outcomes and health-related quality of life. A

Psychosocial screening and follow-up may include, but are not limited to, attitudes about the illness, expectations for medical management and outcomes, affect or mood, general and diabetes-related quality of life, available resources (financial, social, and emotional), and psychiatric history. E

Providers should consider assessment for symptoms of diabetes distress, depression, anxiety, and disordered eating, as well as cog-nitive capacities, using patient-appropriate standardized and validated tools at the initial visit, at periodic intervals, and when there is a change in disease, treatment, or life circumstances. Including caregivers and family members in this assessment is recommended. B

Consider screening older adults (aged ≥65 years) with diabetes for cognitive impairment and depression. B

PREVENTION OR DELAY OF TYPE 2 DIABETES

Recommendations

At least annual monitoring for the development of diabetes in those with prediabetes is suggested. E

Patients with prediabetes should be referred to an intensive behavioral lifestyle intervention program modelled on the Diabetes Prevention Program to achieve and maintain 7% loss of initial body weight and increase moderate-intensity physical activity (such as brisk walking) to at least 150 min/week. A

Metformin therapy for prevention of type 2 diabetes should be considered in those with prediabetes, especially for those with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2, those <60 years of age, and women with prior GDM, and/or those with rising A1C despite lifestyle intervention. A

Screening for and treatment of modifiable risk factors for CVD is suggested for those with prediabetes. B

Intensive lifestyle modification programs have been shown to be very effective (∼58% risk reduction after 3 years). In addition, pharmacologic agents including metformin, α-glucosidase inhibitors, orlistat, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and thiazolidinediones have been shown to decrease incident diabetes to various degrees. Metformin has demonstrated long-term safety as pharmacologic therapy for diabetes prevention.

GLYCEMIC TARGETS

Assessment of Glycemic Control

Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) frequency and timing should be dictated by patients’ specific needs and goals. SMBG is especially important for patients treated with insulin to monitor for and prevent asymptomatic hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. For patients on nonintensive insulin regimens such as those with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin, when to prescribe SMBG and at what testing frequency are less established.

Recommendation

Most patients using intensive insulin regimens (multiple-dose insulin or insulin pump therapy) should perform SMBG prior to meals and snacks, at bedtime, occasionally postprandially, prior to exercise, when they suspect low blood glucose, after treating low blood glucose until they are normoglycemic, and prior to critical tasks such as driving. B

SMBG allows patients to evaluate their individual responses to therapy and assess whether glycemic targets are being achieved. Results of SMBG can be useful in preventing hypoglycemia and adjusting medications (particularly prandial insulin doses), MNT, and physical activity. Evidence also supports a correlation between SMBG frequency and meeting A1C targets.

SMBG accuracy is instrument- and user-dependent. Evaluate each patient’s monitoring technique, both initially and at regular intervals thereafter. The ongoing need for and frequency of SMBG should be reevaluated at each routine visit.

A1C Testing

Recommendations

Perform the A1C test at least two times a year in patients who are meeting treatment goals (and who have stable glycemic control). E

Perform the A1C test quarterly in patients whose therapy has changed or who are not meeting glycemic goals. E

Point-of-care testing for A1C provides the opportunity for more timely treatment changes. E

For patients in whom A1C and measured blood glucose appear discrepant, clinicians should consider the possibilities of hemoglobinopathy or altered red blood cell turnover and the options of more frequent and/or different timing of SMBG or continuous glucose monitoring. Other measures of chronic glycemia such as fructosamine are available, but their linkage to average glucose and their prognostic significance are not as clear as for A1C.

A1C Goals

Recommendations

A reasonable A1C goal for many nonpregnant adults is <7% (53 mmol/mol). A

Providers might reasonably suggest more stringent A1C goals (such as <6.5% [48 mmol/mol]) for selected individual patients if this can be achieved without significant hypoglycemia or other adverse effects of treatment (i.e., polypharmacy). Appropriate patients might include those with a short duration of diabetes, type 2 diabetes treated with lifestyle or metformin only, long life expectancy, or no significant CVD. C

Less stringent A1C goals (such as <8% [64 mmol/mol]) may be appropriate for patients with a history of severe hypoglycemia, limited life expectancy, advanced microvascular or macrovascular complications, extensive comorbid conditions, or long-standing diabetes in whom the goal is difficult to achieve despite DSME, appropriate glucose monitoring, and effective doses of multiple glucose-lowering agents, including insulin. B

The complete 2017 Standards of Care includes additional goals for children and pregnant women.

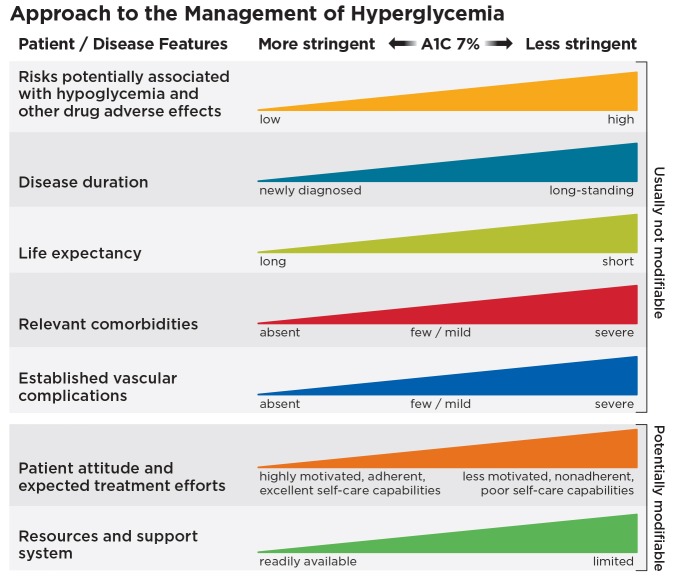

Glycemic control achieved using A1C targets of <7% (53 mmol/mol) has been shown to reduce microvascular complications of diabetes, and, in type 1 diabetes, mortality. There is evidence for cardiovascular benefit of intensive glycemic control after long-term follow-up of people treated early in the course of type 1 and type 2 diabetes; however, optimal A1C targets should be individualized based on several patient-specific and disease-specific factors (Figure 1). Recommended glycemic targets are provided in Table 6. The recommendations include blood glucose levels that appear to correlate with achievement of an A1C of ≤7% (53 mmol/mol).

FIGURE 1.

Depicted are patient and disease factors used to determine optimal A1C targets. Characteristics and predicaments toward the left justify more stringent efforts to lower A1C; those toward the right suggest less stringent efforts. Adapted with permission from Inzucchi et al. Diabetes Care 2015;38:140–149.

TABLE 6.

Summary of Glycemic Recommendations for Many Nonpregnant Adults With Diabetes

| A1C | <7.0% (53 mmol/mol)* |

| Preprandial capillary plasma glucose | 80–130 mg/dL* (4.4–7.2 mmol/L) |

| Peak postprandial capillary plasma glucose† | <180 mg/dL* (10.0 mmol/L) |

More or less stringent glycemic goals may be appropriate for individual patients. Goals should be individualized based on duration of diabetes, age/life expectancy, comorbid conditions, known CVD or advanced microvascular complications, hypoglycemia unawareness, and individual patient considerations.

Postprandial glucose may be targeted if A1C goals are not met despite reaching preprandial glucose goals. Postprandial glucose measurements should be made 1–2 h after the beginning of the meal, generally peak levels in patients with diabetes.

Hypoglycemia

The 2017 Standards of Care provides a new classification of hypoglycemia.

Recommendations

Individuals at risk for hypoglycemia should be asked about symptomatic and asymptomatic hypoglycemia at each encounter. C

Glucose (15–20 g) is the preferred treatment for conscious individuals with hypoglycemia (glucose alert value of ≤70 mg/dL), although any form of carbohydrate that contains glucose may be used. Fifteen minutes after treatment, if SMBG shows continued hypoglycemia, the treatment should be repeated. Once SMBG returns to normal, the individual should consume a meal or snack to prevent recurrence of hypoglycemia. E

Glucagon should be prescribed for all individuals at increased risk of clinically significant hypoglycemia, defined as blood glucose <54 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L), so it is available should it be needed. Caregivers, school personnel, or family members of these individuals should know where it is and when and how to administer it. The use of glucagon is indicated for the treatment of hypoglycemia in people unable or unwilling to consume carbohydrates by mouth. Glucagon administration is not limited to health care professionals. E

Hypoglycemia unawareness or one or more episodes of severe hypoglycemia should trigger reevaluation of the treatment regimen. E

Insulin-treated patients with hypoglycemia unawareness or an episode of clinically significant hypoglycemia should be advised to raise their glycemic targets to strictly avoid hypoglycemia for at least several weeks to partially reverse hypoglycemia unawareness and reduce the risk of future episodes. A

Ongoing assessment of cognitive function is suggested with increased vigilance for hypoglycemia by the clinician, patient, and caregivers if low cognition and/or declining cognition is found. B

OBESITY MANAGEMENT FOR THE TREATMENT OF TYPE 2 DIABETES

Obesity management can delay progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes and may be beneficial in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. In overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes, modest and sustained weight loss has been shown to improve glycemic control and to reduce the need for glucose-lowering medications.

Assessment

Recommendation

At each patient encounter, BMI should be calculated and documented in the medical record. B

In Asian Americans, the BMI cutoff points to define overweight and obesity are lower than in other populations.

Providers should advise overweight and obese patients that higher BMIs increase the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality.

Providers should assess each patient’s readiness to achieve weight loss and jointly determine weight loss goals and intervention strategies.

Diet, Physical Activity, and Behavioral Therapy

Recommendations

Diet, physical activity, and behavioral therapy designed to achieve >5% weight loss should be prescribed for overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes ready to achieve weight loss. A

Such interventions should be high intensity (≥16 sessions in 6 months) and focus on diet, physical activity, and behavioral strategies to achieve a 500–750 kcal/day energy deficit. A

Diets should be individualized; eating patterns that provide the same caloric restriction but differ in protein, carbohydrate, and fat content are equally effective in achieving weight loss. A

For patients who achieve short-term weight loss goals, long-term (≥1-year) comprehensive weight maintenance programs should be prescribed. Such programs should provide at least monthly contact and encourage ongoing monitoring of body weight (weekly or more frequently), continued consumption of a reduced-calorie diet, and participation in high levels of physical activity (200–300 min/week). A

To achieve weight loss of >5%, short-term (3-month) high-intensity lifestyle interventions that use very-low-calorie diets (≤800 kcal/day) or total meal replacements may be prescribed for carefully selected patients by trained practitioners in medical care settings with close medical monitoring. To maintain weight loss, such programs must incorporate long-term comprehensive weight maintenance counseling. B

Pharmacotherapy

Recommendations

When choosing glucose-lowering medications for overweight or obese patients with type 2 diabetes, consider their effect on weight. E

Whenever possible, minimize the medications for comorbid conditions that are associated with weight gain. E

Weight loss medications may be effective as adjuncts to diet, physical activity, and behavioral counseling for selected patients with type 2 diabetes and a BMI ≥27 kg/m2. Potential benefits must be weighed against the potential risks of the medications. A

If a patient’s response to weight loss medications is <5% weight loss after 3 months or if there are any safety or tolerability issues at any time, the medication should be discontinued and alternative medications or treatment approaches should be considered. A

Metabolic Surgery

Recommendations

Metabolic surgery should be recommended to treat type 2 diabetes in appropriate surgical candidates with a BMI ≥40 kg/m2 (BMI ≥37.5 kg/m2 in Asian Americans) regardless of the level of glycemic control or complexity of glucose-lowering regimens and in adults with a BMI of 35.0–39.9 kg/m2 (32.5–37.4 kg/m2 in Asian Americans) when hyperglycemia is inadequately controlled despite lifestyle and optimal medical therapy. A

Metabolic surgery should be considered for adults with type 2 diabetes and a BMI of 30.0–34.9 kg/m2 (27.5–32.4 kg/m2 in Asian Americans) if hyperglycemia is inadequately controlled despite optimal medical control by either oral or injectable medications (including insulin). B

Metabolic surgery should be performed in high-volume centers with multidisciplinary teams who understand and are experienced in the management of diabetes and gastrointestinal (GI) surgery. C

Long-term lifestyle support and routine monitoring of micronutrient and nutritional status must be provided to patients after surgery, according to guidelines for postoperative management of metabolic surgery by national and international professional societies. C

People presenting for metabolic surgery should receive a comprehensive mental health assessment. B Surgery should be postponed in patients with a history of alcohol or substance abuse, significant depression, suicidal ideation, or other mental health conditions until these conditions have been fully addressed. E

People who undergo metabolic surgery should be evaluated to assess their need for ongoing mental health services to help them adjust to medical and psychosocial changes after surgery. C

Several GI operations promote dramatic and durable improvement of type 2 diabetes. Younger age, shorter duration of diabetes (e.g., <8 years), nonuse of insulin, and better glycemic control are consistently associated with higher rates of diabetes remission and/or lower risk of recidivism. Beyond improving glycemia, metabolic surgery has been shown to confer additional health benefits in randomized controlled trials, including greater reductions in CVD risk factors and enhancements in quality of life.

PHARMACOLOGIC APPROACHES TO GLYCEMIC TREATMENT

Pharmacologic Therapy for Type 1 Diabetes

Recommendations

Most people with type 1 diabetes should be treated with multiple daily injection (MDI) therapy including prandial and basal insulin or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII; insulin pump therapy). A

Most individuals with type 1 diabetes should use rapid-acting insulin analogs to reduce hypoglycemia risk. A

Consider educating individuals with type 1 diabetes on matching prandial insulin doses to carbohydrate intake, premeal blood glucose levels, and anticipated physical activity. E

Individuals with type 1 diabetes who have been successfully using CSII should have continued access to this therapy after they turn 65 years of age. E

Pharmacologic Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes

Recommendations

Metformin, if not contraindicated and if tolerated, is the preferred initial pharmacologic agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. A

Long-term use of metformin may be associated with biochemical vitamin B12 deficiency, and periodic measurement of vitamin B12 levels should be considered in metformin-treated patients, especially in those with anemia or peripheral neuropathy. B

Consider initiating insulin therapy (with or without additional agents) in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes who are symptomatic and/or have an A1C ≥10% (86 mmol/mol) and/or blood glucose levels ≥300 mg/dL (16.7 mmol/L). E

If noninsulin monotherapy at maximum tolerated dose does not achieve or maintain the A1C target after 3 months, add a second oral agent, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, or basal insulin. A

A patient-centered approach should be used to guide the choice of pharmacologic agents. Considerations include efficacy, hypoglycemia risk, impact on weight, potential side effects, cost, and patient preferences. E

For patients with type 2 diabetes who are not achieving glycemic goals, insulin therapy should not be delayed. B

In patients with long-standing suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), empagliflozin or liraglutide should be considered because they have been shown to reduce cardiovascular and all-cause mortality when added to standard care. Ongoing studies are investigating the cardiovascular benefits of other agents in these drug classes. B

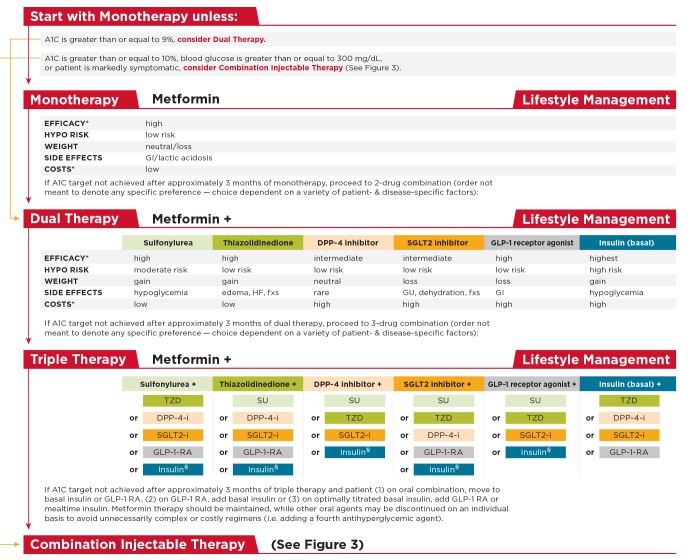

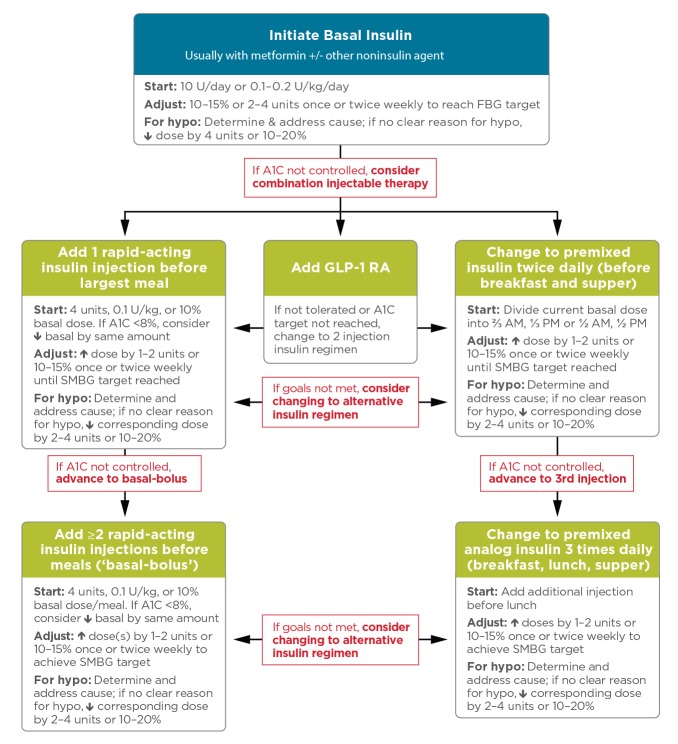

Figure 2 and Figure 3 outline monotherapy and combination therapy emphasizing drugs commonly used in the United States and/or Europe.

FIGURE 2.

Antihyperglycemic therapy in type 2 diabetes: general recommendations. The order in the chart was determined by historical availability and the route of administration, with injectables to the right; it is not meant to denote any specific preference. Potential sequences of antihyperglycemic therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes are displayed, with the usual transition moving vertically from top to bottom (although horizontal movement within therapy stages is also possible, depending on the circumstances). DPP-4-i, DPP-4 inhibitor; fxs, fractures; GI, gastrointestinal; GLP-1 RA, GLP-1 receptor agonist; GU, genitourinary; HF, heart failure; Hypo, hypoglycemia; SGLT2-i, SGLT2 inhibitor; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione. *See original source for description of efficacy categorization. §Usually a basal insulin (NPH, glargine, detemir, degludec). Adapted with permission from Inzucchi et al. Diabetes Care 2015;38:140–149.

FIGURE 3.

Combination injectable therapy for type 2 diabetes. FBG, fasting blood glucose; GLP-1 RA, GLP-1 receptor agonist; hypo, hypoglycemia. Adapted with permission from Inzucchi et al. Diabetes Care 2015;38:140–149.

CVD AND RISK MANAGEMENT

ASCVD is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality for individuals with diabetes and is the largest contributor to the direct and indirect costs of diabetes. In all patients with diabetes, cardiovascular risk factors should be systematically assessed at least annually. These risk factors include hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, family history of premature coronary disease, and albuminuria. Large benefits are seen when multiple risk factors are addressed simultaneously. There is evidence that measures of 10-year coronary heart disease risk among U.S. adults with diabetes have improved significantly over the past decade and that ASCVD morbidity and mortality have decreased.

Blood Pressure Control

Recommendations

Blood pressure should be measured at every routine visit. Patients found to have elevated blood pressure should have blood pressure confirmed on a separate day. B

Most patients with diabetes and hypertension should be treated to a systolic blood pressure goal of <140 mmHg and a diastolic blood pressure goal of 90 mmHg. A

Lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure targets, such as 130/80 mmHg, may be appropriate for individuals at high risk of CVD if they can be achieved without undue treatment burden. C

Patients with confirmed office-based blood pressure >140/90 mmHg should, in addition to lifestyle therapy, have prompt initiation and timely titration of pharmacologic therapy to achieve blood pressure goals. A

Patients with confirmed office-based blood pressure >160/100 mmHg should, in addition to lifestyle therapy, have prompt initiation and timely titration of two drugs to reduce CVD events in patients with diabetes. A

An ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) at the maximum tolerated dose indicated for blood pressure treatment is the recomended first-line treatment for hyperytension in patients with diabetes and urine albumin–to–creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥300 mg/g creatinine A or UACR 30–299 mg/g creatinine. B If one class is not tolerated, the other should be substituted. B

For patients treated with an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or diuretic, serum creatinine/estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and serum potassium levels should be monitored. B

For patients with blood pressure >120/80 mmHg, lifestyle intervention consists of weight loss, if overweight or obese; a DASH-style dietary pattern, including reduced sodium and increased potassium intake; moderation of alcohol intake; and increased physical activity. B

Lipid Management

Recommendations

In adults not taking statins, it is reasonable to obtain a lipid profile at the time of diabetes diagnosis, at an initial medical evaluation, and every 5 years thereafter, or more frequently if indicated. E

Obtain a lipid profile at initiation of statin therapy and periodically thereafter because it may help to monitor the response to therapy and inform adherence. E

Lifestyle modification focusing on weight loss (if indicated); reduction of saturated fat, trans fat, and cholesterol intake; increase in omega-3 fatty acids, viscous fiber, and plant stanols/sterols intake; and increase in physical activity should be recommended to improve the lipid profile in patients with diabetes. A

Intensify lifestyle therapy and optimize glycemic control for patients with elevated triglyceride levels (≥150 mg/dL [1.7 mmol/L]) and/or low HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL [1.0 mmol/L] for men, <50 mg/dL [1.3 mmol/L] for women). C

For patients with fasting triglyceride levels ≥500 mg/dL (5.7 mmol/L), evaluate for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia and consider medical therapy to reduce the risk of pancreatitis. C

In clinical practice, providers may need to adjust intensity of statin therapy based on individual patient response to medication (e.g., side effects, tolerability, LDL cholesterol levels). E

The addition of ezetimibe to moderate-intensity statin therapy has been shown to provide additional cardiovascular benefit compared with moderate-intensity statin therapy alone for patients with recent acute coronary syndrome and LDL cholesterol ≥50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) and should be considered for these patients A and also in patients with diabetes and history of ASCVD who cannot tolerate high-intensity statin therapy. E

Combination therapy (statin/fibrate) has not been shown to improve ASCVD outcomes and is generally not recommended. A However, therapy with statin and fenofibrate may be considered for men with both triglyceride level ≥204 mg/dL (2.3 mmol/L) and HDL cholesterol level ≤34 mg/dL (0.9 mmol/L). B

Combination therapy (statin/niacin) has not been shown to provide additional cardiovascular benefit above statin therapy alone and may increase the risk of stroke and is not generally recommended. A

Table 7 provides recommendations for statin and combination therapy in people with diabetes. Table 8 outlines high- and moderate-intensity statin therapy.

TABLE 7.

Recommendations for Statin and Combination Treatment in People With Diabetes

| Age (years) | Risk Factors | Recommended Statin Intensity* |

| <40 | None | None |

| ASCVD risk factor(s)** | Moderate or high | |

| ASCVD | High | |

| 40–75 | None | Moderate |

| ASCVD risk factors | High | |

| ASCVD | High | |

| ACS and LDL cholesterol ≥50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) or in patients with a history of ASCVD who cannot tolerate high-dose statins | Moderate plus ezetimibe | |

| >75 | None | Moderate |

| ASCVD risk factors | Moderate or high | |

| ASCVD | High | |

| ACS and LDL cholesterol ≥50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) or in patients with a history of ASCVD who cannot tolerate high-dose statins | Moderate plus ezetimibe |

In addition to lifestyle therapy.

ASCVD risk factors include LDL cholesterol ≥100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L), high blood pressure, smoking, chronic kidney disease, albuminuria, and family history of premature ASCVD.

TABLE 8.

High- and Moderate-Intensity Statin Therapy*

| High-Intensity Statin Therapy (Lowers LDL cholesterol by ≥50%) | Moderate-Intensity Statin Therapy (Lowers LDL cholesterol by 30 to <50%) |

| • Atorvastatin 40–80 mg | • Atorvastatin 10–20 mg |

| • Rosuvastatin 20–40 mg | • Rosuvastatin 5–10 mg |

| • Simvastatin 20–40 mg | |

| • Pravastatin 40–80 mg | |

| • Lovastatin 40 mg | |

| • Fluvastatin XL 80 mg | |

| • Pitavastatin 2–4 mg |

Once-daily dosing.

Antiplatelet Agents

Recommendations

Use aspirin therapy (75–162 mg/day) as a secondary prevention strategy in those with diabetes and a history of ASCVD. A

For patients with ASCVD and documented aspirin allergy, clopidogrel (75 mg/day) should be used. B

Dual antiplatelet therapy is reasonable for up to 1 year after an acute coronary syndrome and may have benefits beyond this period. B

Consider aspirin therapy (75–162 mg/day) as a primary prevention strategy in those with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who are at increased cardiovascular risk. This includes most men or women with diabetes aged ≥50 years who have at least one additional major risk factor (family history of premature ASCVD, hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, or albuminuria) and are not at increased risk of bleeding. C

Coronary Heart Disease

Recommendations

In asymptomatic patients, routine screening for coronary artery disease is not recommended because it does not improve outcomes as long as ASCVD risk factors are treated. A

In patients with known ASCVD, use aspirin and statin therapy (if not contraindicated) A, and consider ACE inhibitor therapy C to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.

In patients with prior myocardial infarction, β-blockers should be continued for at least 2 years after the event. B

In patients with symptomatic heart failure, thiazolidinedione treatment should not be used. A

In patients with type 2 diabetes with stable congestive heart failure, metformin may be used if eGFR remains >30 mL/min but should be avoided in unstable or hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure. B

MICROVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS AND FOOT CARE

Intensive diabetes management with the goal of achieving near-normoglycemia has been shown in large, prospective, randomized studies to delay the onset and progression of microvascular complications.

Diabetic Kidney Disease

Recommendations

At least once a year, assess urinary albumin (e.g., spot UACR) and eGFR in patients with type 1 diabetes with a duration of ≥5 years, in all patients with type 2 diabetes, and in all patients with comorbid hypertension. B

Optimize glucose control to reduce the risk or slow the progression of diabetic kidney disease. A

Optimize blood pressure control to reduce the risk or slow the progression of diabetic kidney disease. A

In nonpregnant patients with diabetes and hypertension, either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB is recommended for those with modestly elevated UACR (30–299 mg/g creatinine) B and is strongly recommended for those with UACR >300 mg/g creatinine and/or eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. A

Screening for albuminuria can be most easily performed by UACR in a random spot urine collection. UACR determined for two of three specimens collected within a 3- to 6-month period should be abnormal before considering a patient to have albuminuria.

Blood pressure levels <140/90 mmHg in diabetes are recommended to reduce CVD mortality and slow chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression.

With reduced eGFR, drug dosing may require modification. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revised guidance for the use of metformin in diabetic kidney disease in 2016, recommending use of eGFR instead of serum creatinine to guide treatment and expanding the pool of patients with kidney disease for whom metformin treatment should be considered. The revised FDA guidance states that metformin is contraindicated in patients with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, eGFR should be monitored while taking metformin, the benefits and risks of continuing treatment should be reassessed when eGFR falls to <45 mL/min/1.73 m2, metformin should not be initiated for patients with an eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2, and metformin should be temporarily discontinued at the time of or before iodinated contrast imaging procedures in patients with an eGFR of 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Other glucose-lowering medications also require dose adjustment or discontinuation at low eGFR.

Recommendations for the management of CKD in people with diabetes are summarized in Table 9.

TABLE 9.

Management of CKD in Diabetes

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | Recommended Management |

| All patients | • Yearly measurement of UACR, serum creatinine, and potassium |

| 45–60 | • Refer to a nephrologist if possibility for nondiabetic kidney disease exists (duration of type 1 diabetes <10 years, persistent albuminuria, abnormal findings on renal ultrasound, resistant hypertension, rapid fall in eGFR, or active urinary sediment on urine microscopic examination) |

| • Consider the need for dose adjustment of medications | |

| • Monitor eGFR every 6 months | |

| • Monitor electrolytes, bicarbonate, hemoglobin, calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone at least yearly | |

| • Assure vitamin D sufficiency | |

| • Vaccinate against hepatitis B virus | |

| • Consider bone density testing | |

| • Refer for dietary counseling | |

| 30–44 | • Monitor eGFR every 3 months |

| • Monitor electrolytes, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, hemoglobin, albumin, and weight every 3–6 months | |

| • Consider the need for dose adjustment of medications | |

| <30 | • Refer to a nephrologist |

Diabetic Retinopathy

Recommendations

Optimize glycemic control to reduce the risk or slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy. A

Optimize blood pressure and serum lipid control to reduce the risk or slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy. A

Adults with type 1 diabetes should have an initial dilated and comprehensive eye examination by an ophthalmologist or optometrist within 5 years after the onset of diabetes. B

Patients with type 2 diabetes should have an initial dilated and comprehensive eye examination by an ophthalmologist or optometrist at the time of the diabetes diagnosis. B

If there is no evidence of retinopathy for one or more annual eye exams and glycemia is well controlled, then exams every 2 years may be considered. If any level of diabetic retinopathy is present, subsequent dilated retinal examinations should be repeated at least annually by an ophthalmologist or optometrist. If retinopathy is progressing or sight-threatening, then examinations will be required more frequently B

Neuropathy

Recommendations

All patients should be assessed for diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) starting at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and 5 years after the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at least annually thereafter. B

Assessment for distal symmetric polyneuropathy should include a careful history and assessment of either temperature or pinprick sensation (for small-fiber function) and vibration sensation using a 128-Hz tuning fork (for large-fiber function). All patients should have annual 10-g monofilament testing to identify feet at risk of ulceration and amputation. B

Optimize glucose control to prevent or delay the development of neuropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes A and to slow the progression of neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. B

Either pregabalin or duloxetine are recommended as initial pharmacologic treatments for neuropathic pain in diabetes. A

Foot Care

Recommendations

Perform a comprehensive foot evaluation each year to identify risk factors for ulcers and amputations. B

All patients with diabetes should have their feet inspected at every visit. C

Obtain a history of ulceration, amputation, Charcot foot, angioplasty or vascular surgery, cigarette smoking, retinopathy, and renal disease and assess current symptoms of neuropathy (pain, burning, numbness) and vascular disease (leg fatigue, claudication). B

The examination should include inspection of the skin, assessment of foot deformities, neurological assessment (10-g monofilament testing), and vascular assessment, including pulses in the legs and feet. B

Patients who are ≥50 years of age and any patients with symptoms of claudication or decreased or absent pedal pulses should be referred for further vascular assessment as appropriate. C

A multidisciplinary approach is recommended for individuals with foot ulcers and high-risk feet (e.g., dialysis patients and those with Charcot foot, prior ulcers, or amputation). B

Refer patients who smoke or who have a history of prior lower-extremity complications, loss of protective sensation, structural abnormalities, or peripheral arterial disease to foot care specialists for ongoing preventive care and lifelong surveillance. C

Provide general preventive foot self-care education to all patients with diabetes. B

The use of specialized therapeutic footwear is recommended for high-risk patients with diabetes, including those with severe neuropathy, foot deformities, or history of amputation. B

OLDER ADULTS

Recommendations

Consider the assessment of medical, mental, functional, and social geriatric domains in older adults to provide a framework to determine targets and therapeutic approaches for diabetes management. C

Screening for geriatric syndromes may be appropriate in older adults experiencing limitations in their basic and instrumental activities of daily living because they may affect diabetes self-management and be related to health-related quality of life. C

Annual screening for early detection of mild cognitive impairment or dementia is indicated for adults ≥65 years of age. B

Older adults (≥65 years of age) with diabetes should be considered a high-priority population for depression screening and treatment. B

Hypoglycemia should be avoided in older adults with diabetes. It should be assessed and managed by adjusting glycemic targets and pharmacologic interventions. B

Older adults who are cognitively and functionally intact and have significant life expectancy may receive diabetes care with goals similar to those developed for younger adults. C

Glycemic goals for some older adults might reasonably be relaxed using individual criteria, but hyperglycemia leading to symptoms or risk of acute hyperglycemic complications should be avoided in all patients. C

Screening for diabetes complications should be individualized in older adults. Particular attention should be paid to complications that would lead to functional impairment. C

Treatment of hypertension to individualized target levels is indicated in most older adults. C

Treatment of other cardiovascular risk factors should be individualized in older adults considering the time frame of benefit. Lipid-lowering therapy and aspirin therapy may benefit those with a life expectancy at least equal to the time frame of primary prevention or secondary intervention trials. E

When palliative care is needed in older adults with diabetes, strict blood pressure control may not be necessary, and withdrawal of therapy may be appropriate. Similarly, the intensity of lipid management can be relaxed, and withdrawal of lipid-lowering therapy may be appropriate. E

Consider diabetes education for the staff of long-term care facilities to improve the management of older adults with diabetes. E

Treatment Goals

The care of older adults with diabetes is complicated by their clinical and functional heterogeneity. Providers caring for older adults with diabetes must take this heterogeneity into consideration when setting and prioritizing treatment goals (Table 10).

TABLE 10.

Framework for Considering Treatment Goals for Glycemia, Blood Pressure, and Dyslipidemia in Older Adults With Diabetes

| Patient Characteristics/ Health Status | Rationale | Reasonable A1C Goal (% [mmol/mol])‡ | Fasting or Preprandial Glucose (mg/dL [mmol/L]) | Bedtime Glucose (mg/dL [mmol/L]) | Blood Pressure (mmHg) | Lipids |

| Healthy (few coexisting chronic illnesses, intact cognitive and functional status) | Longer remaining life expectancy | <7.5 (58) | 90–130 (5.0–7.2) | 90–150 (5.0–8.3) | <140/90 | Statin unless contraindicated or not tolerated |

| Complex/intermediate (multiple coexisting chronic illnesses* or 2+ instrumental ADL impairments or mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment) | Intermediate remaining life expectancy, high treatment burden, hypoglycemia vulnerability, fall risk | <8.0 (64) | 90–150 (5.0–8.3) | 100–180 (5.6–10.0) | <140/90 | Statin unless contraindicated or not tolerated |

| Very complex/poor health (LTC or end-stage chronic illnesses** or moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment or 2+ ADL dependencies) | Limited remaining life expectancy makes benefit uncertain | <8.5† (69) | 100–180 (5.6–10.0) | 110–200 (6.1–11.1) | <150/90 | Consider likelihood of benefit with statin (secondary prevention more so than primary) |

This represents a consensus framework for considering treatment goals for glycemia, blood pressure, and dyslipidemia in older adults with diabetes. The patient characteristic categories are general concepts. Not every patient will clearly fall into a particular category. Consideration of patient and caregiver preferences is an important aspect of treatment individualization. Additionally, a patient’s health status and preferences may change over time. ADL, activities of daily living.

A lower A1C goal may be set for an individual if achievable without recurrent or severe hypoglycemia or undue treatment burden.

Coexisting chronic illnesses are conditions serious enough to require medications or lifestyle management and may include arthritis, cancer, congestive heart failure, depression, emphysema, falls, hypertension, incontinence, stage 3 or worse CKD, myocardial infarction, and stroke. By “multiple,” we mean at least three, but many patients may have five or more.

The presence of a single end-stage chronic illness, such as stage 3–4 congestive heart failure or oxygen-dependent lung disease, CKD requiring dialysis, or uncontrolled metastatic cancer, may cause significant symptoms or impairment of functional status and significantly reduce life expectancy.

A1C of 8.5% (69 mmol/mol) equates to an estimated average glucose of ∼200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L). Looser A1C targets >8.5% (69 mmol/mol) are not recommended because they may expose patients to more frequent higher glucose values and the acute risks from glycosuria, dehydration, hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome, and poor wound healing.

Older adults with diabetes are likely to benefit from control of other cardiovascular risk factors. Evidence is strong for treatment of hypertension. There is less evidence for lipid-lowering and aspirin therapy, although the benefits of these interventions are likely to apply to older adults whose life expectancies equal or exceed the time frames of clinical prevention trials.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Special care is required in prescribing and monitoring pharmacologic therapy in older adults. Factors include hypoglycemia, cost, and coexisting conditions (e.g., renal status). The patient’s living situation must be considered because it may affect diabetes management and support.

Treatment in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Nursing Homes

Management of diabetes is unique in the long-term care (LTC) setting (i.e., nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities). Individualization of health care is important for all patients. However, practical guidance is needed for both medical providers and LTC staff and caregivers.

Older adults with diabetes in LTC are especially vulnerable to hypoglycemia because of their disproportionately higher number of complications and comorbidities. Alert strategies should be in place for hypoglycemia (blood glucose ≤70 mg/dL [3.9 mmol/L]) and hyperglycemia (blood glucose >250 mg/dL [13.9 mmol/L]).

For patients in the LTC setting, special attention should be given to nutritional considerations, end-of-life care, and changes in diabetes management with respect to advanced disease. Acknowledging the limited benefit of intensive glycemic control in people with advanced disease can guide A1C goals and determine the use or withdrawal of medications. For more information, see ADA’s position statement “Management of Diabetes in Long-Term Care and Skilled Nursing Facilities.”

CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

Children and adolescents with diabetes have unique aspects of care such as changes in insulin sensitivity related to physical growth and sexual maturation, ability to provide self-care, supervision in the child care and school environment, and neurological vulnerability to hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia (in young children), as well as possible adverse neurocognitive effects of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Attention to family dynamics, developmental stages, and physiological differences related to sexual maturity are all essential in developing and implementing an optimal diabetes regimen.

Support Services

Recommendations

Youth with type 1 diabetes and parents/caregivers (for patients <18 years of age) should receive culturally sensitive and developmentally appropriate individualized DSME and DSMS according to national standards at diagnosis and routinely thereafter. B

At diagnosis and during routine follow-up care, assess psychosocial issues and family stresses that could affect adherence to diabetes management and provide appropriate referrals to trained mental health professionals, preferably experienced in childhood diabetes. E

Starting at puberty, preconception counseling should be incorporated into routine diabetes care for all girls of childbearing potential. A

Glycemic Control

Recommendations

An A1C goal of <7.5% (58 mmol/mol) is recommended across all pediatric age-groups. E

Autoimmune Conditions

Recommendations

Assess for the presence of autoimmune conditions associated with type 1 diabetes soon after the diagnosis and if symptoms develop. E

Hypertension

Recommendations

Blood pressure should be measured at each routine visit. Children found to have high-normal blood pressure (systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥90th percentile for age, sex, and height) or hypertension (systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥95th percentile for age, sex, and height) should have elevated blood pressure confirmed on three separate days. B

ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be considered for the initial pharmacologic treatment of hypertension, to be initiated after reproductive counseling and implementation of effective birth control due to the potential teratogenic effects of both drug classes. E

The goal of treatment is blood pressure consistently <90th percentile for age, sex, and height. E

Blood pressure measurements should be determined using the appropriate size cuff and with the child seated and relaxed. Lifestyle modifications, including dietary modification and increased exercise, should be implemented for 3–6 months. If target blood pressure has not been reached within 3–6 months, pharmacotherapy should be initiated.

Dyslipidemia

Recommendations

Obtain a fasting lipid profile on children ≥10 years of age soon after diabetes diagnosis (after glucose control has been established). E

If lipids are abnormal, annual monitoring is reasonable. If LDL cholesterol values are within the accepted risk levels (<100 mg/dL [2.6 mmol/L]), a lipid profile repeated every 3–5 years is reasonable. E

After the age of 10 years, the addition of a statin is suggested in patients who, despite MNT and lifestyle changes, continue to have LDL cholesterol >160 mg/dL (4.1 mmol/L) or LDL cholesterol >130 mg/dL (3.4 mmol/L) and one or more CVD risk factors, initiated after reproductive counseling and implementation of effective birth control due to the potential teratogenic effects of statins. E

The goal of therapy is an LDL cholesterol value <100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L). E

Nephropathy

Recommendations

Annual screening for albuminuria with a random spot urine sample for UACR should be considered once a child has had type 1 diabetes for 5 years. B

Retinopathy

Recommendations

An initial dilated and comprehensive eye examination is recommended at age ≥10 years or after puberty has started, whichever is earlier, once a youth has had type 1 diabetes for 3–5 years. B

After the initial examination, annual routine follow-up is generally recommended. Less frequent examinations, every 2 years, may be acceptable on the advice of an eye care professional. E

Neuropathy

Recommendations

Consider an annual comprehensive foot exam for a child at the start of puberty or at age ≥10 years, whichever is earlier, once the youth has had type 1 diabetes for 5 years. E

MANAGEMENT OF DIABETES IN PREGNANCY

Preexisting Diabetes

Recommendations

Starting at puberty, preconception counseling should be incorporated into routine diabetes care for all girls of childbearing potential. A

Family planning should be discussed and effective contraception should be prescribed and used until a woman is prepared and ready to become pregnant. A

Preconception counseling should address the importance of glycemic control as close to normal as is safely possible, ideally A1C <6.5% (48 mmol/mol), to reduce the risk of congenital anomalies. B

Women with preexisting type 1 or type 2 diabetes who are planning pregnancy or who have become pregnant should be counseled on the risk of development and/or progression of diabetic retinopathy. Dilated eye examinations should occur before pregnancy or in the first trimester, and then patients should be monitored every trimester and for 1 year postpartum as indicated by degree of retinopathy and as recommended by the eye care provider. B

GDM

Recommendations

Lifestyle change is an essential component of GDM management and may suffice for treatment for many women. Medications should be added if needed to achieve glycemic targets. A

Insulin is the preferred medication for treating hyperglycemia in GDM because it does not cross the placenta to a measurable extent. Metformin and glyburide may be used, but both cross the placenta to the fetus, with metformin likely crossing to a greater extent than glyburide. All oral agents lack long-term safety data. A

Metformin, when used to treat polycystic ovary syndrome and induce ovulation, need not be continued once pregnancy has been confirmed. A

General Principles for the Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy

Recommendations

Potentially teratogenic medications (e.g., ACE inhibitors and statins) should be avoided in sexually active women of childbearing age who are not using reliable contraception. B

Fasting and postprandial SMBG are recommended in both GDM and preexisting diabetes in pregnancy to achieve glycemic control. Some women with preexisting diabetes should also test blood glucose preprandially. B

The A1C target in pregnancy is 6–6.5% (42–48 mmol/mol); <6% (42 mmol/mol) may be optimal if this can be achieved without significant hypoglycemia, but the target may be relaxed to <7% (53 mmol/mol) if necessary to prevent hypoglycemia. B

Preconception Counseling

Observational studies show an increased risk of diabetic embryopathy, especially anencephaly, microcephaly, congenital heart disease, and caudal regression directly proportional to elevations in A1C during the first 10 weeks of pregnancy.

Preconception counseling visits should include rubella, syphilis, hepatitis B virus, and HIV testing, as well as Pap smear, cervical cultures, blood typing, prescription of prenatal vitamins (with at least 400 µg folic acid), and smoking cessation counseling if indicated.

Diabetes-specific testing should include A1C, thyroid-stimulating hormone, creatinine, and UACR. The medication list should be reviewed for potentially teratogenic drugs, and patients should be referred for a comprehensive eye exam. Women with preexisting diabetic retinopathy will need close monitoring during pregnancy to ensure that retinopathy does not progress.

Preconception counseling resourc-es tailored for adolescents are available at no cost through the ADA.

Postpartum Care

Because GDM may represent preexisting undiagnosed type 2 or even type 1 diabetes, women with GDM should be tested for persistent diabetes or prediabetes at 4–12 weeks postpartum with a 75-g OGTT using the nonpregnancy criteria as outlined in the section on classification and diagnosis of diabetes above.

Because GDM is associated with increased maternal risk for diabetes, women should also be tested every 1–3 years thereafter if the 4- to 12-week 75-g OGTT is normal, with frequency of testing depending on other risk factors, including family history, prepregnancy BMI, and need for insulin or oral glucose-lowering medication during pregnancy. Ongoing evaluation may be performed with any recommended glycemic test (e.g., A1C, FPG, or 75-g OGTT using nonpregnant thresholds).

DIABETES CARE IN THE HOSPITAL, NURSING HOME, AND SKILLED NURSING FACILITY

Recommendations

Perform an A1C for all patients with diabetes or hyperglycemia admitted to the hospital if not performed in the prior 3 months. B