Abstract

Background: Multiple myeloma (MM) remains an incurable cancer characterized by accumulation of malignant plasma cells in the bone marrow (BM). The mechanism underlying MM homing to BM is poorly elucidated.

Methods: The clinical significance of migration inhibitory factor (MIF) expression was examined by analyzing six independent gene expression profile databases of primary MM cells using the Student’s t test and Kaplan-Meier test. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to examine MIF expression. In vivo bioluminescent imaging was used to determine MM cell localization and treatment efficacy in human MM xenograft mouse models, with three to four mice per group. MM cell attachment to BM stromal cells (BMSCs) was monitored by cell adhesion assay. MIF regulation of the expression of adhesion molecules was determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. Statistical tests were two-sided.

Results: High levels of MIF were detected in MM BM (MIF level in BM plasma: healthy = 10.72 ± 5.788 ng/mL, n = 5; MM = 1811 ± 248.7 ng/mL, n = 10; P < .001) and associated with poor survival of patients (Kaplan-Meier test for MM OS: 87 MIFhigh patients, 86 MIFlow patients, P = .02). Knocking down MIF impaired MM cell adhesion to BMSCs in vitro and led to formation of extramedullary tumors in SCID mice. MIF acted through surface receptor CXCR4 and adaptor COPS5 to regulate the expression of adhesion molecules ALCAM, ITGAV, and ITGB5 on MM cells. More importantly, MIF-deficient MM cells were sensitive to chemotherapy in vitro when cocultured with BMSCs and in vivo. MIF inhibitor 4-IPP sensitized MM cells to chemotherapy.

Conclusions: MIF is an important player and a novel therapeutic target in MM. Inhibiting MIF activity will sensitize MM cells to chemotherapy.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable plasma cell cancer characterized by tumor cell accumulation in the bone marrow (BM) (1,2). The nature of MM as a bone cancer poses additional difficulties in disease management. Not only does the BM microenvironment confer MM chemoresistance, but bone cancer also causes bone pain, pathologic fractures, and hypercalcemia that require treatment (3). MM cell homing to BM is an active process throughout the disease pathogenesis. MM progression involves BM homing in which tumor cells from primary BM site(s) enter the peripheral circulation and migrate to secondary BM sites in the axial skeleton (4). However, the mechanism of MM BM homing is still poorly understood.

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is a soluble pro-inflammatory cytokine ubiquitously expressed by different types of cells (5,6). MIF has three cell surface receptors: CD74, CXCR4, and CXCR2 (7). Receptor binding stimulates MIF uptake by cells and enables interaction between MIF and COPS5 (also known as Jun activation domain-binding protein or Jab1) (8), which may be critical for activation and expression of downstream inflammatory factors (5). MIF may also function in cancer as MIF overexpression has been noted in a panel of human cancers (9).

The function of MIF in MM is unknown. Our preliminary study suggested that MIF-deficient MM cells had aberrant tumor growth in bone. Therefore, we hypothesized that MIF regulated MM BM homing.

Methods

Patient Samples

BM aspirates from MM patients (n = 10) and healthy donors (n = 5) were processed as described (10). Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded BM sections were from five MM patients and five healthy donors. Patients and healthy donors were informed for research use of their samples by written consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Cleveland Clinic.

Cells and Products

Human MM cell lines ARP-1, MM.1S, RPMI8226, CAG, U266, and ARK were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Lonza, Switzerland), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. In serum starvation cell culture, cells were cultured under the same conditions, except no fetal bovine serum was added. Further details are given in the Supplementary Materials (available online).

Mice

To generate the human MM xenograft mouse model, luciferase-expressing MM cells (ARP-1 and MM.1S), either control-knockdown (CTR-KD) or target-gene-KD, were intravenously inoculated into six- to eight-week-old female SCID mice, with three to four mice per group (10). All mouse studies complied with protocols approved by the Cleveland Clinic IACUC committee.

In Vivo Confocal Microscopy

In vivo confocal microscopy was performed as described (11). Further details are given in the Supplementary Materials (available online).

Cell Migration Assay

Freshly isolated hind leg bone from SCID mice was cut into half, and 1 × 105 CFSE-labeled MM cells, either CTR-KD or MIF-KD, were injected directly into the bone marrow. The bones were placed in 35 mm dish and soaked in 1 mL RPMI 1640 complete medium. Cell migration was visualized by the IncuCyte ZOOM live-cell imaging system (ESSEN BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP) assay was performed using a ChIP assay kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Further details are given in the Supplementary Materials (available online).

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from cells using an RNeasy MiniKit (Qiagen, Germany). Target gene expression was analyzed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using the SYBR green real-time PCR system (Applied Bio Systems, Waltham, MA). MIF expression was measured with primers (forward) GCAGAACCGCTCCTACAG and (reverse) CTTAGGC GAAG GTGG AGTTG.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

MIF concentration in BM plasma or cell culture supernatant was examined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical Analysis

All data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. The Student’s t test was used to compare two experimental groups. A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant, except when multiple comparisons we performed where Bonferroni-corrected significance levels were used to preserve the statistical significance level at .05. Survival rate was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier estimates and log-rank tests. In some experiments, linear regression analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5, and R2 was calculated. Statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

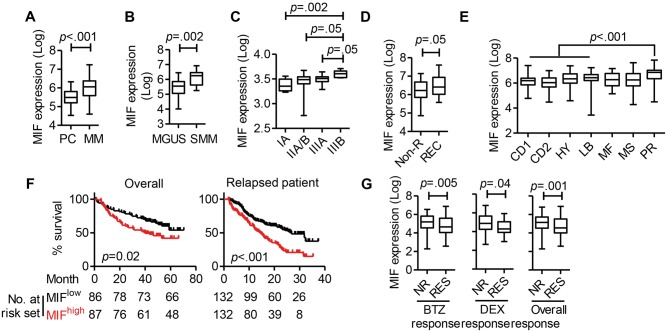

Clinical Significance of MIF Expression in MM

We downloaded six independent MM-related microarray datasets from Oncomine (Supplementary Table 1, available online). Based on analysis of the datasets from the University of Arkansas for Medical Science (12), MM cells had statistically significantly higher MIF expression than normal plasma cells (PCs) (mean ± SD: PC = 5.503 ± 0.072; PC = 5.969 ± 0.064, P < .001) (Figure 1A). Moreover, MIF expression was higher in MM cells from patients with smoldering MM (SMM) than those from patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS; MGUS = 5.443 ± 0.089, SMM = 6.069 ± 0.146, P = .002) (Figure 1B). Using Agnelli et al. (13) data, we found that MM patients in latest stages (IIIB) had statistically significantly higher MIF expression as compared with those with early disease (IA) (P = .002) (Figure 1C). Using Carrasco et al. data, we showed that recurrent MM cells had statistically significantly higher MIF expression than those without recurrence at one year (P = .049) (Figure 1D) (14).

Figure 1.

Clinical significance of migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in multiple myeloma. A) Macrophage MIF expression in normal plasma cells (PC, n = 37) and myeloma cells (MM, n = 74). The y-axis indicates the median log value of MIF, retrieved from the original dataset. B) MIF expression in purified plasma cells of patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS, n = 44) or smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM, n = 12). C) MIF expression according to MM stage (IA, n = 15; IIA/B, n = 16; IIIA, n = 11; IIIB, n = 6). D) MIF expression in patients without recurrence (Non-R, n = 38) and with recurrence (REC, n = 26). E) MIF expression according to MM subgroups (CD1 and CD2 = cyclin D translocation; HY = hyperdiploid; LB = low bone disease; MF and MS = c-MAF and MAFB activation and MMSET and FGFR3 activation; PR = progression), identified by gene expression profiling in Zhan et al. (CD1, n = 28; CD2, n = 60; HY, n = 116; LB, n = 58; MF, n = 37; MS, n = 68; PR, n = 47) (13). F) Overall survival according to high MIF (hiMIF) and low MIF expression (loMIF) (left), and survival in patients with relapse (right). G) MIF expression in patients with differential drug responses, no response (Non-R) vs response (RES) to bortezomib (BTZ, n = 85 for each NR and RES) treatment (left) or dexamethasone (DEX, n = 42 for NR and n = 28 for RES) treatment (right). Student’s t test was used to compare two samples. C) MIF expression of MM cells from different disease stage patients was compared separately with those with latest disease, so the Bonferroni-corrected statistical significance level was used as P < .05 / 3 = .017, P < .01 / 3 = .0034. E) MIF expression of four moderate-risk MM subgroups (CD1, CD2, HY, LB) was compared separately with the MM progression subgroup, so the Bonferroni-corrected statistical significance level was applied as P < .05 / 4 = .0125, P < .01 / 4 = .0025. F) Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival with a P value from a log-rank test. The error bar represents standard deviation. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Zhan et al. classified MM based on gene mutations and characteristic molecular expression patterns (15). Cluster analysis identified MM subgroups (CD1 and CD2: cyclin D translocation; HY: hyperdiploid; LB: low bone disease; MF and MS: c-MAF and MAFB activation and MMSET and FGFR3 activation; and PR: progression). As our analysis of MIF showed (Figure 1E), patients in the PR cluster, which is a signature of progressive disease (15), also had statistically significantly higher MIF expression than others (P < .001).

Our analysis of Zhan et al. data showed that patients with higher MIF expression had shorter overall survival than those with lower expression (87 MIFhigh patients, 86 MIFlow patients, P = .02) (Figure 1F, left panel) (15). The same was true in patients with relapse (132 MIFhigh patients, 132 MIFlow patients, P < .001) (Figure 1F, right panel) (16). Finally, analysis of data from Mulligan et al. (16) showed that nonresponders had statistically significantly higher MIF expression than responders and that this was true for both bortezomib- and dexamethasone-treated groups (for overall response, nonresponders = 5.074 ± 0.076, RES = 4.701 ± 0.084, P = .001) (Figure 1G). Overall, microarray data analyses strongly suggested that MIF expression by malignant plasma cells may be a risk factor in MM.

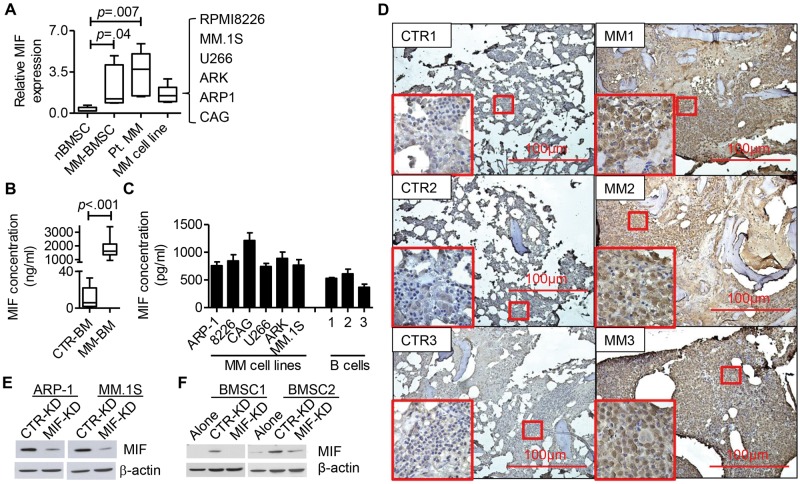

MIF Expression in MM BM

Next, we examined MIF expression in MM BM. qPCR analysis indicated that both primary MM cells, MM cell lines, and BMSCs overexpressed MIF as compared with control BMSCs (Figure 2A). MIF protein expression was statistically significantly higher in MM BM plasma than the control (CTR-BM = 10.72 ± 5.788, MM-BM = 1811 ± 248.7, P < .001) (Figure 2B). MIF protein was detected in the cultures of MM cell lines (Figure 2C), indicating that MM cells secrete MIF. As MM cells secreted high amounts of MIF protein as compared with the levels of MIF mRNA, a post-transcriptional regulation of MIF expression is suggested. Immunohistochemistry analysis of MM and healthy BM showed that MM BM had increased MIF expression (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Migration inhibitory factor (MIF) expression in multiple myeloma. A) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of MIF expression in healthy donor bone marrow (BM) stromal cells (CTR BM stromal cell [nBMSC], n = 6), multiple myeloma (MM) patient CD138– BM cells (MM-BMSC, n = 6), primary MM cells (Pt. MM, n = 6), and MM cell lines (MM cell line, 6 MM cell lines). The value was normalized to the fold MIF expression in ARP-1 cells. B) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results for MIF expression in MM BM plasma (MM BM, n = 10) and healthy BM plasma (CTR BM, n = 5). C) ELISA results for MIF expression in cell culture supernatant. Cells, 2 × 105 each, were cultured in 500 μl medium for 24 hours. The culture supernatants were assessed by ELISA for MIF. D) BM biopsies from healthy donors (CTR) or MM patients (MM) were analyzed by immunohistochemistry staining for MIF (brown staining). Three representatives of five individual samples are shown. E) Western blot showing the expression of MIF in CTR- and MIF-KD ARP-1 and MM.1S. F) BMSCs from two different donors were cultured in transwells, alone (BM) or cocultured with MM cells (CTR-KD or MIF-KD) for three days (BM+MM). MIF expression in BMSCs was assessed by western blot. Student’s t test was used to compare two samples. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Next, we knocked down MIF by infecting MM cells with MIF shRNA plus GFP lentivirus and selected GFP+-stable cell lines with consistently reduced MIF expression (MIF-KD) (Figure 2E). CTR-KD and MIF-KD MM cells showed no difference in cell survival, proliferation, or drug response in vitro (data not shown). Interestingly, coculture with CTR-KD but not MIF-KD MM cells upregulated MIF protein expression by normal BMSCs (Figure 2F). Taken together, our results indicated that MM BM overexpresses MIF.

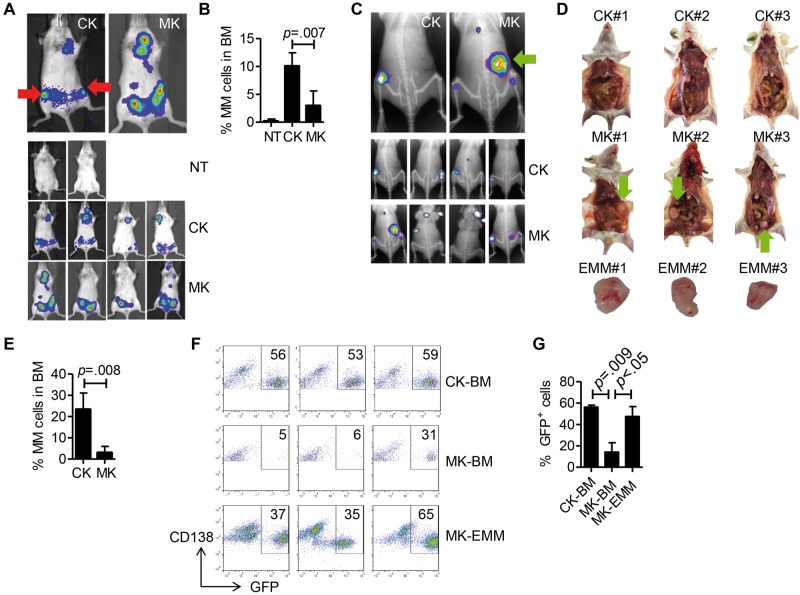

Autocrine MIF and Myeloma Bone Tumor Formation

To study the function of autocrine MIF in MM, we injected MIF-KD or CTR-KD MM cells to SCID-mice and monitored tumor development by bioluminescence imaging. CTR-KD MM cells formed tumors in the hind leg bone and joint whereas MIF-KD MM cells formed tumors mainly in the abdomen two to three weeks after tumor injection (Figure 3A). At late stages (at and after week 4), CTR-KD MM cells also formed extramedullary tumors. We focused on tumors in the posterior limb because there are no organs in this region; therefore, any tumor formation within this area is likely to be bone tumor. CTR-KD ARP-1-inoculated mice had statistically significantly more MM cells in hind leg BM than those bearing MIF-KD tumors (CTR-KD = 10.05 ± 1.199, MIF-KD = 2.95 ± 1.319, P = .007) (Figure 3B). Similarly, CTR-KD MM.1S-bearing mice had predominantly bone tumors in the hind leg region whereas MIF-KD MM.1S-bearing mice had tumor formation at both intramedullary and extramedullary sites (Figure 3C). Gross pathology showed that MIF-KD MM.1S-inoculated mice had large extramedullary tumors in the abdomen whereas CTR-KD cell-inoculated mice had none (Figure 3D). Flow cytometry analyses confirmed that mice bearing CTR-KD MM.1S tumors had more MM cell infiltration in the hind leg BM (P = .008) (Figure 3E). Before inoculation, more than 99% of MIF-KD or CTR-KD MM cells were GFP+; however, by analyzing the ratio of GFP+ cells to total CD138+ MM cells, we found that intramedullary tumors in MIF-KD MM.1S-bearing mice had a statistically significantly lower proportion of GFP+ cells than extramedullary tumors (P = .047), suggesting that more intramedullary tumor cells retained MIF expression in vivo (Figure 3, F and G). Overall, these data suggest that autocrine MIF may play a role in regulating MM cell homing to or retention in BM in vivo.

Figure 3.

Autocrine migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and myeloma bone tumor formation. A) CTR-KD (CK) or MIF-KD (MK) ARP-1 cells were intravenously inoculated in SCID mice (2 million cells per mouse, 4 mice per group). SCID mice without tumor cell injection were used as controls (no treatment, NT). At four weeks after inoculation, mice were assessed by in vivo bioluminescent imaging. Top images: representative animals. Bottom images: all animals tested. Red arrows indicate tumor formation in hind leg bone/joint. B) Mice in (A) were killed, and the hind leg bone marrow (BM) cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD138+ multiple myeloma (MM) cells. MM cells as the percentage of the total BM cells are plotted. C) Similar to the experiment in (A), MM.1S cells were inoculated in SCID mice and assessed by in vivo bioluminescence and x-ray imaging. The green arrow indicates extramedullary tumor. D) Gross pathology of MM.1S-inoculated mice. The green arrow points to extramedullary tumor in the abdomen. E) Percentage of MM cells in hind leg BM. F) Flow cytometry analysis of GFP+ cells and cells with shRNA expression, expressed as a percentage of total MM cells (CD138+). Samples tested included MM cells from CTR-KD tumor-bearing mouse BM (CK-BM), MIF-KD tumor-bearing mouse BM (MK-BM), and extramedullary tumor cells from MIF-KD tumor-bearing mice isolated in (E) (MK-EMM). Result from three different mice. G) Quantification of results shown in (F). The Student’s t test was used to compare two samples. All statistical tests were two-sided.

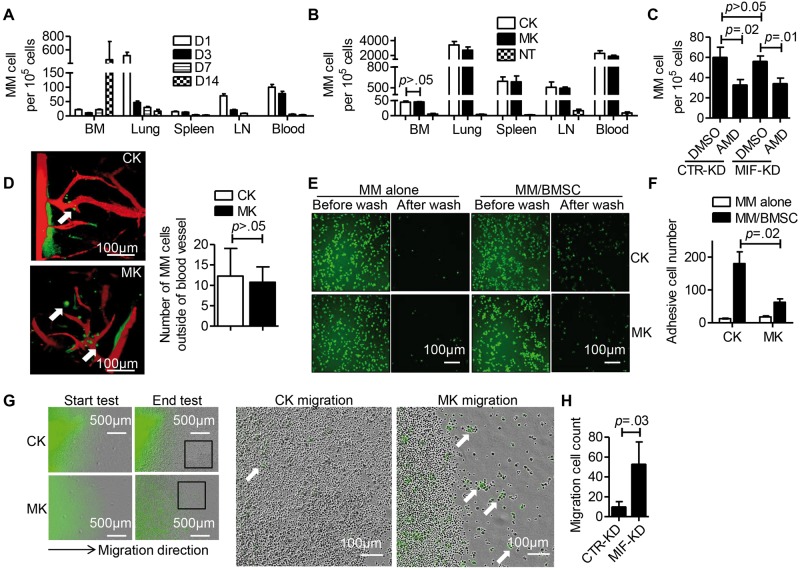

MIF and MM Adhesion to BMSCs

MM cell homing to bone involves multiple steps such as cell chemotaxis, cell penetration into BM, and cell adhesion. To examine the mechanism, mice injected with ARP-1 MM cells were killed at different time points and analyzed for tumor cells in different organs. The percentage of MM cells decreased in lung, spleen, celiac lymph nodes, and peripheral blood from day 1 to day 14 after cell injection (Figure 4A) whereas the percentage of MM cells in hind leg BM remained constant until day 7, after which large numbers of MM cells were detected. We then examined whether MIF knockdown affected MM chemotaxis to BM. We counted MM cells in different organs at two hours and found that similar numbers of CTR-KD and MIF-KD cells had migrated to BM (P > .05) (Figure 4B). However, CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100, which inhibits the CXCR4/SDF-1 axis and reduces MM migration to BM (15), effectively inhibited MM cell migration to BM with the same effects on both CTR-KD and MIF-KD cells (Figure 4C), suggesting that MIF does not control MM chemotaxis to BM.

Figure 4.

Migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and adhesion molecule expression on multiple myeloma (MM) cells. A) ARP-1 cells were intravenously inoculated into SCID mice (6 million cells per mouse, 3 mice per group). The mice were killed at days 1, 3, 7, and 14 after the tumor cell injection. The numbers of CD138+ MM cells in bone marrow (BM), lung, spleen (SP), lymph-node (LN), and peripheral blood (PB) were determined by flow cytometry. B) ARP-1 cells, either CTR-KD (CK) or MIF-KD (MK), were intravenously inoculated in SCID mice (6 million cells per mouse, 3 mice per group). Two SCID mice without tumor cell injection were used as control (no treatment = NT). At two hours after injection, the mice were killed and the number of CD138+ MM cells in different organs was determined by flow cytometry. C) ARP-1 cells, CTR-KD or MIF-KD, were pretreated with or without CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100 (50 μM for 2 hours, AMD or CTR, respectively). The cells were intravenously inoculated in SCID mice (6 million cells per mouse, 3 mice per group). At two hours after injection, CD138+ MM cells in BM were determined by flow cytometry. D) CFSE-labeled ARP-1 cells, either CTR-KD or MIF-KD, were intravenously inoculated in SCID mice (6 million cells per mouse, 2 mice per group). At two hours after injection, CD138+ MM cells in skull BM were examined by in vivo confocal microscopy. Left: white arrow indicates MM cell (green) penetration of skull BM; blood vessels are shown in red. One representative image for one of two mice is shown. Right: MM cells outside the blood vessels were quantified and showed no difference between CK- and MK-inoculated mice. E) Cell adhesion assay visualized under fluorescent microscopy. CTR-KD or MIF-KD ARP-1 cells were prelabeled with CFSE (green). Representative assays of BM stomal cells (BMSCs) from two healthy individuals are shown (BMSCs from 4 individuals were tested in total). F) Quantification of adherent cells. G) Quantification of the migrated MM cells in cell migration assay. Hind leg bones were isolated from SCID mice and placed in 35 mm dishes with complete cell culture medium. CFSE-labeled ARP-1 cells (green), either CTR-KD or MIF-KD, were directly injected into the bone marrow. The dish was placed in the IncuCyte ZOOM live-cell imaging system within a cell culture incubator and observed in real time for three days. H) The number of extramedullary migrated MM (green) cells was calculated. The Student’s t test was used to compare two samples. B) MM cell number in different tissues of three mouse groups was compared separately, so the Bonferroni-corrected statistical significance level was used as *P < .05 / 3 = .017, **P < .01 / 3 = .0034. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Using in vivo confocal microscopy, we examined cell extravasation. At two hours after inoculation, MM cells could be detected in skull BM. In both CTR-KD and MIF-KD ARP-1 or MM.1S cell-inoculated mice, we detected MM cells outside the blood vessels, with no difference between the groups (P > .05) (Figure 4D; Supplementary Figure 1, available online). Thus, these findings suggested that MIF does not affect MM extravasation to BM in vivo.

Next, we determined whether MIF regulated MM cell adhesion to BMSCs (Supplementary Figure 2A, available online). Equal numbers of CTR-KD and MIF-KD ARP-1 cells were CFSE labeled and cultured either alone or with BMSCs. As shown in Figure 4, E and F, adhesion of MIF-KD MM cells to BMSCs was statistically significantly reduced as compared with CTR-KD (P = .02).

Finally, we examined ex vivo migration of MM cells out of murine BM (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figure 2B, available online). MIF-KD MM cell-injected bone had more extramedullary tumor cell migration than those injected with CTR-KD (CTR-KD = 9.333 ± 3.383, MIF-KD = 52.33 ± 13.22, P = .03) (Figure 4, G and H), likely as a result of reduced cell adhesion to BM stroma. Taken together, these results indicated that autocrine MIF may regulate MM cell retention in BM by affecting their adhesion to BMSCs but not their chemotactic or extravasation capacity.

MIF and Adhesion Molecule Expression on MM Cells

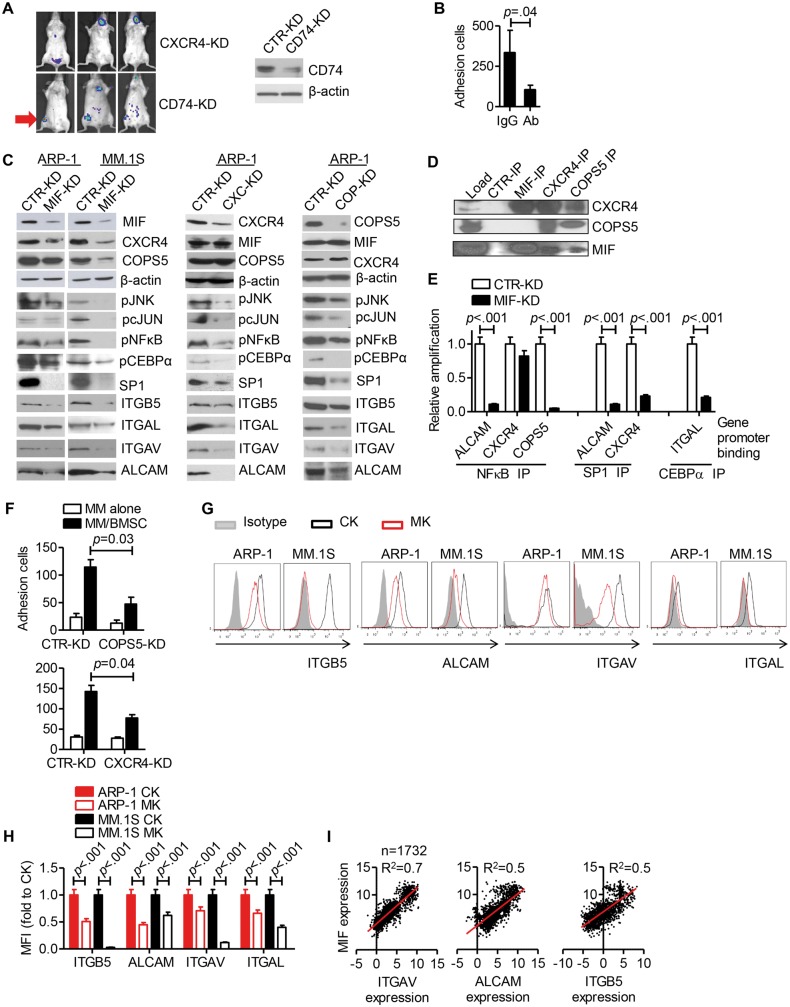

To examine the molecular basis, we first examined MIF receptor expression on MM cells. Both MM cell lines and primary MM cells expressed MIF receptors CD74 and CXCR4 but not CXCR2 (Supplementary Figure 3, available online). CD74-KD ARP-1 and control cells formed similar tumors in bone whereas CXCR4-KD ARP-1 cells formed only extramedullary tumors, similar to MIF-KD (Figure 5A). Thus, these findings suggested that CXCR4 was involved in MIF-mediated regulation of MM affinity for BM.

Figure 5.

Migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and adhesion molecule expression on multiple myeloma (MM) cells. A) CD74-KD or CXCR4-KD ARP-1 cells were intravenously inoculated in SCID mice (2 million cells per mouse, 3 mice per group). At four weeks after injection, the mice were assessed by in vivo bioluminescent imaging. The red arrow indicates tumor formation in hind leg bone/joint. CD74 knockdown in ARP-1 cells was verified by western blotting. B) Adhesion of ARP-1 cells to bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) in the presence of ALCAM, ITGAV, and ITGAL blocking antibody cocktail (Ab = each blocking antibody final concentration at 10 μg/mL). C) Western blot of signaling molecules in MIF-KD, CXCR4-KD, and COPS5-KD MM cells. D) Immunoprecipitation using ARP-1 cell lysate. E) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP) assay results showing the binding of transcription factors to the ALCAM, CXCR4, COPS5, and ITGAL gene promoter regions in CTR-KD or MIF-KD ARP-1 cells. F) Adhesion of CTR-KD and COPS5-KD (upper panel) or CXCR4-KD (lower panel) to BMSCs. MM cells alone served as controls. G) Same mouse model as shown in (A) and (C) was established. Flow cytometry analysis of adhesion molecules expression on BM GFP+ cells (MM cells with shRNA expression). Samples tested included MM cells (ARP-1-inoculated mice or MM.1S-inoculated mice) from CTR-KD tumor-bearing mouse BM (CK), MIF-KD tumor-bearing mouse BM (MK). One representative of two mice. H) Quantification of flow cytometry analysis by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). I) Analysis of aggregated data for adhesion molecules and MIF coexpression. The association between MIF and target gene expression was analyzed by linear regression with R2 calculated. The Student’s t test was used to compare two samples. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Second, we performed a microarray analysis to determine gene expression of CTR-KD, MIF-KD, and CXCR4-KD ARP-1 cells and focused on adhesion molecules (Supplementary Table 2, available online). Several adhesion molecules, such as ALCAM and ITGAV, were downregulated in both MIF-KD and CXCR4-KD (Supplementary Figure 4, A and B, available online). Blocking these adhesion molecules by antibodies statistically significantly reduced MM cell adhesion to BMSCs (P = .04) (Figure 5B). These findings suggested that MIF may regulate MM adhesion to BMMCs by modulating the expression of ALCAM, ITGAV, and ITGAL on MM cells.

Third, we elucidated the molecular mechanism underlying MIF regulation of the adhesion molecules. By searching a transcription factor database, we found that CEBPα, NFκB, cJUN, and SP1 can regulate ALCAM, ITGAV, and ITGAL gene expression (Supplementary Figure 5, available online). Previous studies suggested that crosstalk exists between COPS5 and the cJun or NFκB pathways (18,19). Knocking down MIF, CXCR4, or COPS5 decreased the expression of phosphorylated c-Jun, JNK, NFκB, and CEBPα, and the protein level of SP-1 (Figure 5C). As a result, expression of ALCAM, ITGAV, and ITGAL was also downregulated. Interestingly, MIF-KD MM cells also had downregulated CXCR4 and COPS5 expression while MIF expression in CXCR4-KD or COPS5-KD MM cells remained unchanged.

Fourth, we examined the MIF-CXCR4-COPS5 axis by co-immunoprecipitation. MIF, CXCR4, and COPS5 had protein-protein interactions as MIF co-immunoprecipitated with CXCR4, CXCR4 with MIF and COPS5, and COPS5 with MIF and CXCR4 (Figure 5D). Next, we examined the transcription factor binding to target gene promoter regions by chromatin immunoprecipitation. NFκB could bind the promoters of ALCAM, CXCR4, and COPS5; SP1 binds with those of ALCAM and CXCR4; and CEBPα binds with the ITGAL promoter (Figure 5E). In MIF-KD MM cells, reduced levels of promoters were detected because the amounts of the transcription factors were reduced (Figure 5E). COPS5-KD or CXCR4-KD MM cells also had reduced adhesion to BMSCs in vitro (P < .05) (Figure 5F).

Finally, we examined the expression of the adhesion molecules in MM cells in vivo. MIF-KD MM in BM had a decreased expression of ITGB5, ALCAM, ITGAV, and ITGAL (Figure 5, G and H). Furthermore, the relationship between MIF and the expression of these adhesion molecules was supported by the results of meta-analyses of data from 1732 MM patients, which showed a highly positive association between the levels of MIF expression and ITGAV, ALCAM, or ITGB5 expression in primary MM cells (Figure 5I; Supplementary Table 1, available online).

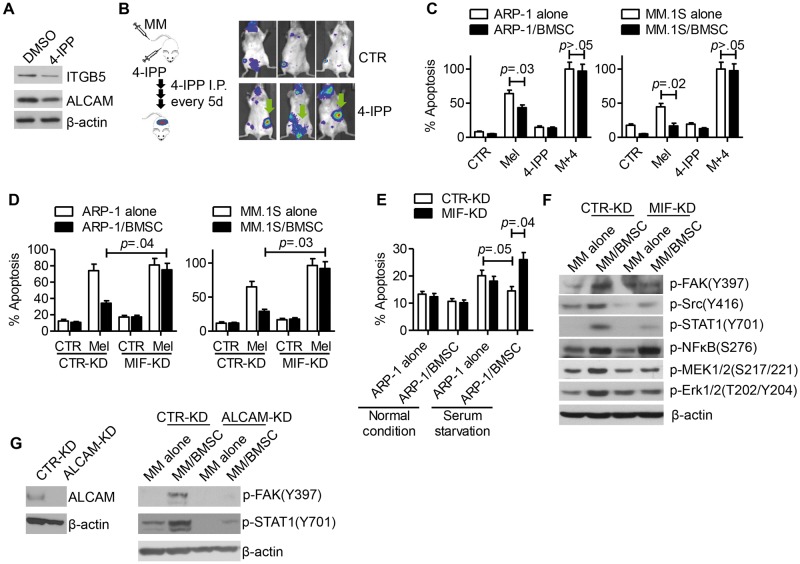

BMSC-Mediated MM Chemoresistance In Vitro With MIF Inhibition

We analyzed the effect of the MIF inhibitor 4-IPP (20) on MM cells and showed that 4-IPP treatment downregulated the expression of ALCAM and ITGB5 on MM cells (Figure 6A). Co-injection of MM cells and 4-IPP led to more extramedullary tumors in SCID mice (Figure 6B), confirming the role of MIF inhibition in reducing MM affinity for BM in vivo.

Figure 6.

Bone marrow stomal cell (BMSC)–mediated multiple myeloma (MM) chemoresistance in vitro with migration inhibitory factor (MIF) inhibition. A) ARP-1 cells were treated with 4-IPP (80 μM) for 24 hours and examined by western blot for expression of ITGB5 and ALCAM. B) Left: diagram of the animal study. Right: in vivo bioluminescent imaging of 4-IPP-treated mice (n = 3/group). C) ARP-1 (left panel) and MM.1S (right panel) cells, cultured alone or cocultured with BMSCs, were treated with melphalan (Mel, 15 μM), 4-IPP (80 μM), or combination of both for 24 hours. Apoptotic cells were examined by flow cytometry for annexin V and propidium iodide-positive cells. D) CTR-KD or MIF-KD ARP-1 (left panel) or MM.1S (right panel) were cocultured with BMSCs and treated with or without melphalan (Mel, 15 μM) for 24 hours. Apoptotic cells were examined by flow cytometry. E) CTR-KD or MIF-KD ARP-1 cells were cultured alone or cocultured with BMSCs in complete medium or in medium without serum for 24 hours. Cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. Western blotting analysis of integrin downstream cell signaling molecules in (F) CTR-KD or MIF-KD ARP-1 cells or (G) CTR-KD or ALCAM-KD ARP-1 cells after coculture with BMSCs for four hours. The Student’s t test was used to compare two samples. All statistical tests were two-sided.

In vitro assay showed that the MIF inhibitor 4-IPP, which alone did not induce apoptosis in MM cells in vitro, not only abrogated BMSC-mediated protection of MM cell apoptosis but also enhanced the efficacy of melphalan in killing MM cells (P < .05) (Figure 6C). 4-IPP also promoted anti-MM efficacy of bortezomib in vitro (data not shown). Such findings suggested a role for MIF in MM chemoresistance. Interestingly, 4-IPP also sensitized MM cells to chemotherapy in the absence of BMSCs, suggesting that this inhibitor may have other functional effects on MM cells in addition to MIF inhibition. Furthermore, BMSCs statistically significantly protected CTR-KD but not MIF-KD MM cells from melphalan (P < .05) (Figure 6D)- or serum starvation-induced (Figure 6E) apoptosis. Coculture with BMSCs stimulated FAK-Src-Erk survival signaling activation in CTR-KD but not in MIF-KD MM cells (Figure 6F). Similarly, in ALCAM-KD MM cells, no FAK or STAT1 signaling activation was induced in coculture with BMSCs (Figure 6G). Overall, our results suggested that MIF might be a promising target in MM therapy.

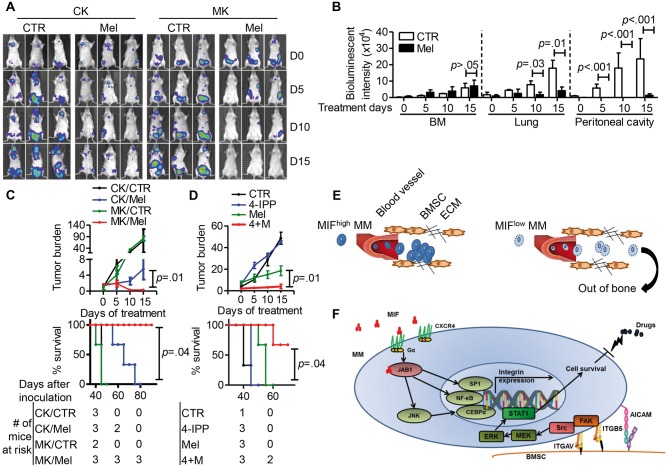

Effect of MIF Inhibitor and Chemotherapy for MM Treatment In Vivo

Using the same MM mouse model, we examined MIF-targeting therapy in vivo. During the 15-day treatment period, melphalan reduced the size of extramedullary tumors but had a limited effect on intramedullary tumors in the hind leg bone/joint (Figure 7A). Bioluminescence intensity analysis confirmed that melphalan statistically significantly reduced the tumor loads in the lung and abdomen but not in BM (P < .05) (Figure 7B). On the other hand, because MIF-KD MM cells mainly formed extramedullary tumors, by day 15 of melphalan treatment, tumors were completely eliminated in MIF-KD MM-bearing mice (Figure 7A). Treatment effectiveness was further confirmed by examining tumor burden and mouse survival (Figure 7C). Finally, we examined combination therapy. Our results showed that although 4-IPP alone had no therapeutic effect in vivo, it statistically significantly enhanced the effectiveness of melphalan (P < .05) (Figure 7D) and prolonged the survival of mice bearing human MM (Figure 7D). We repeated the in vivo studies with another MM cell line and obtained similar results (Supplementary Figure 6, available online).

Figure 7.

Effect of migration inhibitory factor (MIF) knockdown or inhibition and chemotherapy on myeloma. A) In vivo bioluminescent imaging showing tumor location and burden in mice bearing CTR-KD (CK) or MIF-KD (MK) ARP-1 tumors. MM cells were intravenously inoculated in SCID mice (2 million cells per mouse, 3 mice per group). Three to four weeks after tumor development, mice were treated with intraperitoneal injections of either PBS (CTR) or melphalan (Mel, 100 μg per mouse, every 3 days) and examined by in vivo bioluminescent imaging at days 0, 5, 10, and 15 after treatment. B) Quantification of bioluminescence intensity at bone marrow (BM), lung, and Peritoneal cavity of CTR-KD (CK) mice after treatment. C) Tumor burden, analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), of mouse plasma human κ chain concentration, normalized to control (top panel), and mouse survival (bottom panel) in mice bearing CTR-KD (CK) or MIF-KD (MK) ARP-1 tumors treated with melphalan. D) Tumor burden, analyzed by ELISA, of mouse plasma human κ chain concentration, normalized to control (top panel), and survival (bottom panel) in mice bearing ARP-1 tumors treated with PBS (CTR), 4-IPP (0.5 mg per mouse, every 3 days), melphalan (Mel, 100 μg per mouse, every 3 days), and their combination (4+M). E) Diagrams showing the model of MIF regulation of MM adhesion to BM. F) Diagram showing MIF downstream cell signaling in MM cells that regulate MM cell adhesion to BM stroma and chemoresistance. The Student’s t test was used to compare two samples. The survival plots in (C) and (D) show Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival and comparisons using the log-rank test. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Taken together, our findings suggest that MM-derived MIF regulates MM affinity for BM. MIF-KD MM cells had impaired attachment to BMSCs (Figure 7E). MIF-CXCR4-COPS5 axis regulates the gene transcription of the adhesion molecules, such as ALCAM, ITGB5, and ITGAV. Downregulation of the adhesion molecules on MM cells not only impairs MM retention in the BM but also sensitizes MM cells to chemotherapy (Figure 7F).

Discussion

In this study, we identified MIF as a novel regulator of MM BM retention. Our results showed that MM cells overexpressed MIF, which was associated with advanced disease stage and poorer patient survival. Although knockdown of MIF in MM cells did not affect MM cell growth and survival in vitro, MIF-KD MM cells exhibited reduced affinity for BM and formed mainly extramedullary tumors in a human MM xenograft SCID mouse model. We further showed that MIF regulated the expression of several adhesion molecules on MM cells and MIF-KD MM exhibited decreased cell adhesion to BMSCs, explaining at least in part why MIF-KD MM generated more extramedullary tumors in vivo.

The homing and its molecular basis are key to the understanding of MM tumorigenesis, progression, and metastasis (21). Alsayed et al. have shown that the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis regulates MM chemotaxis to BM (17). Stessman and colleagues showed that the reduced CXCR4 expression in MM patients was associated with better survival (22). Furthermore, migration and invasion of MM cells to BM may require the E/P-selectins and their common receptor P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (23). Other factors, such as the integrin ITGAL, the sialyltransferase ST3GAL6, and SDC1, may also contribute to MM BM homing (11,24,25). Our study reveals for the first time that autocrine MIF in MM cells is an important player in MM cell affinity to BM.

The function of MIF in cancer metastasis has been investigated. Drews-Elger et al. showed that MIF inhibition decreased metastatic tumor burden in breast cancer (26). Long et al. found that MIF upregulation was associated with pancreatic cancer lymphatic metastasis (27). Ren and colleagues found that MIF downregulation reduced metastatic neuroblastoma (28). Similar findings were also observed in colon cancer, in which MIF knockdown inhibited liver metastasis (29). Most of the studies suggested that MIF promotes metastasis. MIF deficiency was usually associated with decreased cancer metastasis. However, our data showed that MM-derived MIF retained tumor cells in the BM and knockdown of MIF resulted in impaired formation of BM tumors and formation of extramedullary tumors. These results suggest that MIF may function differently in different cancer cell types.

MM BM confers MM drug resistance and provides a tumor-promoting microenvironment (30). Our data indicate that MM-derived MIF may play an important role in conditioning MM tumor microenvironment. Because normal BMSCs secreted low MIF and MM-derived MIF was necessary to upregulate MIF expression in BMSCs, it is reasonable to speculate that normal BMSCs, when interacting with MIFlow MM cells, could not produce more MIF to overcome the shortage of this protein. Therefore, normal BM stroma could not retain MIF-KD MM cells.

Because knockdown or inhibition of MIF expression in MM cells impaired MM affinity for BM, MIF may be a potential treatment target. Our data showed that treatment with the MIF inhibitor 4-IPP led to formation of extramedullary tumors, and those tumors were more sensitive to the chemotherapeutic melphalan. More encouragingly, MIF-blocking antibodies have been tested in clinical trials for treatment of solid tumors and lupus nephritis. Therefore, treating MM by inhibiting MIF may not have any substantial technical obstacle. We are conducting further studies to address the potential of MIF-targeted treatment in MM.

There are several limitations of this study. First, because there is no commercially available MIF-blocking antibody, we used a MIF inhibitor 4-IPP in the study. This chemical compound may have multiple targets in the cells, and its translational perspective may be limited. Second, we had small numbers of mice in each group of our in vivo study.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA138402, R01 CA138398, R01 CA163881), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (6969-15), and the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (to QY); the Cleveland Clinic RPC fund, National Science Foundation of China (81470363), and Sichuan University Faculty Start Fund (to YZ); and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81120108018 to ZC).

Notes

The study sponsors had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

YZ, QW, ZC, and QY initiated the work and designed and performed the majority of the experiments; YZ and QY wrote the manuscript; JQ, YLu, YLi, EB, MZ, and JD performed the experiments; YQ performed the statistical analyses; FR, EH, and JY provided samples and critical suggestions for this study.

We thank the myeloma tissue banks of West China Hospital, Cleveland Clinic, and MD Anderson Cancer Center for providing samples. The authors thank Cassandra Talerico, PhD, a salaried employee of the Cleveland Clinic, for substantive editing and comments.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Tonon G, et al. Understanding multiple myeloma pathogenesis in the bone marrow to identify new therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(8):585–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podar K, Chauhan D, Anderson KC. Bone marrow microenvironment and the identification of new targets for myeloma therapy. Leukemia. 2009;23(1):10–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palumbo A, Rajkumar SV, San Miguel JF, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus statement for the management, treatment, and supportive care of patients with myeloma not eligible for standard autologous stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):587–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghobrial IM. Myeloma as a model for the process of metastasis: implications for therapy. Blood. 2012;120(1):20–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishihira J. Molecular function of macrophage migration inhibitory factor and a novel therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1271:53–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calandra T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor and host innate immune responses to microbes. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35(9):573–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bucala R. MIF re-discovered: pituitary hormone and glucocorticoid-induced regulator of cytokine production. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1996;7(1):19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleemann R, Grell M, Mischke R, et al. Receptor binding and cellular uptake studies of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): use of biologically active labeled MIF derivatives. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22(3):351–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lippitz BE. Cytokine patterns in patients with cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):e218–e228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Y, Yang J, Qian J, et al. PSGL-1/selectin and ICAM-1/CD18 interactions are involved in macrophage-induced drug resistance in myeloma. Leukemia. 2013;27(3):702–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glavey SV, Manier S, Natoni A, et al. The sialyltransferase ST3GAL6 influences homing and survival in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2014;124(11):1765–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhan F, Hardin J, Kordsmeier B, et al. Global gene expression profiling of multiple myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, and normal bone marrow plasma cells. Blood. 2002;99(5):1745–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agnelli L, Bicciato S, Mattioli M, et al. Molecular classification of multiple myeloma: a distinct transcriptional profile characterizes patients expressing CCND1 and negative for 14q32 translocations. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(29):7296–7306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrasco DR, Tonon G, Huang Y, et al. High-resolution genomic profiles define distinct clinico-pathogenetic subgroups of multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(4):313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhan F, Huang Y, Colla S, et al. The molecular classification of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108(6):2020–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulligan G, Mitsiades C, Bryant B, et al. Gene expression profiling and correlation with outcome in clinical trials of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Blood. 2007;109(8):3177–3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alsayed Y, Ngo H, Runnels J, et al. Mechanisms of regulation of CXCR4/SDF-1 (CXCL12)-dependent migration and homing in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2007;109(7):2708–2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orel L, Neumeier H, Hochrainer K, et al. Crosstalk between the NF-kappaB activating IKK-complex and the CSN signalosome. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14(6B):1555–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shackleford TJ, Claret FX. JAB1/CSN5: a new player in cell cycle control and cancer. Cell Div. 2010;5:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winner M, Meier J, Zierow S, et al. A novel, macrophage migration inhibitory factor suicide substrate inhibits motility and growth of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(18):7253–7257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuehl WM, Bergsagel PL. Multiple myeloma: evolving genetic events and host interactions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(3):175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stessman HA, Mansoor A, Zhan F, et al. Reduced CXCR4 expression is associated with extramedullary disease in a mouse model of myeloma and predicts poor survival in multiple myeloma patients treated with bortezomib. Leukemia. 2013;27(10):2075–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azab AK, Quang P, Azab F, et al. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand regulates the interaction of multiple myeloma cells with the bone marrow microenvironment. Blood. 2012;119(6):1468–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asosingh K, Vankerkhove V, Van Riet I, et al. Selective in vivo growth of lymphocyte function- associated antigen-1-positive murine myeloma cells. Involvement of function-associated antigen-1-mediated homotypic cell-cell adhesion. Exp Hematol. 2003;31(1):48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanderson RD, Yang Y. Syndecan-1: a dynamic regulator of the myeloma microenvironment. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25(2):149–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drews-Elger K, Iorns E, Dias A, et al. Infiltrating S100A8+ myeloid cells promote metastatic spread of human breast cancer and predict poor clinical outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;148(1):41–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long J, Luo G, Liu C, et al. Development of a unique mouse model for pancreatic cancer lymphatic metastasis. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(5):1662–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren Y, Chan HM, Fan J, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo by targeting macrophage migration inhibitory factor in human neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2006;25(25):3501–3508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun B, Nishihira J, Yoshiki T, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor promotes tumor invasion and metastasis via the Rho-dependent pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(3):1050–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raab MS, Podar K, Breitkreutz I, et al. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2009;374(9686):324–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.