Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Positive margins are associated with poor prognosis among patients with oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). However, wide variation exists in the margin sampling technique.

OBJECTIVE

To determine the effect of the margin sampling technique on local recurrence (LR) in patients with stage I or II oral tongue SCC.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

A retrospective study was conducted from January 1, 1986, to December 31, 2012, in 5 tertiary care centers following tumor resection and elective neck dissection in 280 patients with pathologic (p)T1-2 pN0 oral tongue SCC. Analysis was conducted from June 1, 2013, to January 20, 2015.

INTERVENTIONS

In group 1 (n = 119), tumor bed margins were not sampled. In group 2 (n = 61), margins were examined from the glossectomy specimen, found to be positive or suboptimal, and revised with additional tumor bed margins. In group 3 (n = 100), margins were primarily sampled from the tumor bed without preceding examination of the glossectomy specimen. The margin status (both as a binary [positive vs negative] and continuous [distance to the margin in millimeters] variable) and other clinicopathologic parameters were compared across the 3 groups and correlated with LR.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Local recurrence.

RESULTS

Age, sex, pT stage, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, and adjuvant radiation treatment were similar across the 3 groups. The probability of LR-free survival at 3 years was 0.9 and 0.8 in groups 1 and 3, respectively (P = .03). The frequency of positive glossectomy margins was lowest in group 1 (9 of 117 [7.7%]) compared with groups 2 and 3 (28 of 61 [45.9%] and 23 of 95 [24.2%], respectively) (P < .001). Even after excluding cases with positive margins, the median distance to the closest margin was significantly narrower in group 3 (2 mm) compared with group 1 (3 mm) (P = .008). The status (positive vs negative) of margins obtained from the glossectomy specimen correlated with LR (P = .007), while the status of tumor bed margins did not. The status of the tumor bed margin was 24% sensitive (95% CI, 16%-34%) and 92% specific (95% CI, 85%-97%) for detecting a positive glossectomy margin.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

The margin sampling technique affects local control in patients with oral tongue SCC. Reliance on margin sampling from the tumor bed is associated with worse local control, most likely owing to narrower margin clearance and greater incidence of positive margins. A resection specimen–based margin assessment is recommended.

The principle of en bloc resection has been a standard of surgical oncology. While en bloc resection still remains a key surgical principle, the extension of surgical oncology into more complex anatomical areas and technological advances (ie, endoscopic mucosal resections, transoral laser microsurgery) highlight the need to reconsider the potential merits of piecemeal tumor removal.1,2 Piecemeal resections are controversial because they result in fragmentation of the removed specimen, compromising its integrity and complicating confident histopathologic evaluation for the adequacy of excision. While in certain areas of the body, such as the skull base or larynx, piecemeal tumor removal may be justified by anatomical constraints3 or functional imperatives4 (ie, preservation of voice and deglutition), the apparently increasing use of the piecemeal approach in anatomically simpler and more accessible parts of the human body is more difficult to understand. Some oncologic resections, including prostatectomies, partial nephrectomies, and breast-conserving surgical procedures, are now composed of multiple parts, with margins being distinct and separate from the main resected specimen.5–8 In such scenarios, it becomes unclear as to what is an adequate resection and what is the margin.

Unlike other areas in the human body, early (pathologic [p]T1-2 pN0) carcinomas of the oral tongue are easily exposed through the mouth, making en bloc resection highly feasible. Since partial glossectomies are performed by physicians in several surgical specialties, including otolaryngologists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, and general surgeons, standardizing margin sampling is especially important.9

Quality initiatives by the American Head and Neck Society (AHNS) emphasize the importance of obtaining a negative margin in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10 However, the approach to margin sampling varies considerably from surgeon to surgeon.11,12 Consistent with the general trends in surgical oncology, there are 2 main approaches to obtaining margins in patients undergoing partial glossectomies: specimen driven and defect driven.9 In the specimen-driven approach, the glossectomy specimen is sent en bloc to the pathologist, who then samples margins from the specimen itself. In a defect-driven scenario, the surgeon performs a partial glossectomy and then obtains several tissue samples from the tumor bed or wound. In the latter scenario, tumor bed sampling is not guided by assessment of the margin from the actual glossectomy specimen.

It was previously demonstrated in a group of 126 patients with early stage SCC of the oral tongue that sampling margins from the tumor bed was associated with worse local control.13 To further validate this finding, we evaluated the effect of margin sampling technique on local recurrence (LR) in a larger multi-institutional cohort of 280 patients with pT1-2 pN0 SCC of the oral tongue.

Methods

Study Population

Medical and pathology records were reviewed for oral tongue SCC treated surgically from January 1, 1986, to December 31, 2012. Analysis was conducted from June 1, 2013, to January 20, 2015. The following 5 institutions took part in this study: Southern California Permanente Medical Group, Woodland Hills; The University of Alabama at Birmingham; the University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany; the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and The Ottawa Hospital/University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. All 5 institutions followed the same inclusion criteria:

pT1 or pT2 primary SCC of the oral tongue;

No evidence of cervical lymph node metastases (pN0) following elective neck dissection. All patients considered clinically N0 in whom elective neck dissection revealed lymph nodes with metastatic SCC (pN+) were excluded;

Conventional SCC morphologic features (ie, sarcomatoid, verrucous, and hybrid variants of SCC were excluded);

Lack of preoperative treatment (patients were excluded if they had a history of head and neck SCC, surgery, or radiation to the oral cavity);

Presence of SCC in the glossectomy specimen (28 patients without residual carcinoma in the glossectomy specimen following diagnostic biopsy were excluded).

This work was approved by the Department of Pathology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Total Quality Council and Institutional Review Board, as well as Institutional Review Board authorization performed under the direction of Southern California Permanente Medical Group relating to human subjects in research. A subset of patients was previously described.13–15

Medical records and surgical pathologic findings were reviewed for clinical variables, including age, sex, smoking and alcohol use, and TNM classification as per the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual.16 Medical records were also reviewed for information on patient status at last follow-up, LR or regional recurrence and/or late metastasis, second primary cancer, and type of adjuvant treatment.

Histologic sections were re-reviewed, and the following data were collected: perineural invasion, angiolymphatic invasion, depth of invasion, and tumor size, as previously described.13 Margins assessed from the actual glossectomy specimen are referred to as glossectomy margins. Margins obtained from the tumor bed (also known as margins from the wound, cavity, defect, or patient) are referred to as tumor bed margins. Margins were sampled from the glossectomy specimen at the time of initial evaluation by pathologists at the contributing institution with adequate documentation of margin sampling in surgical pathology reports (ie, tissue section summary, inking code, radial or shave nature of the margin) in all but 7 patients.

The presence of invasive or in situ carcinoma at the margin was considered a positive margin. The status of glossectomy margins and tumor bed margins was examined as a binary variable (positive vs negative) and as a continuous variable (distance to the margin from the invasive tumor front in millimeters).

Margin Sampling and Surgical Workflow Analysis

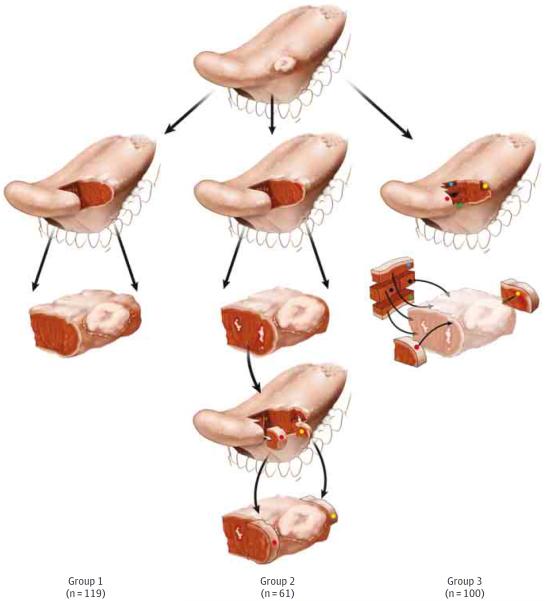

The surgical workflow for all patients was categorized according to the surgeon's preferred approach to margin sampling and surgical intraoperative findings (Figure 1).13 Such workflow analysis was made possible by the routine documentation in all surgical pathology reports of the number and labeling of parts and of intraoperative consultations.

Figure 1.

Schematic Representation of the 3 Workflow Groups

An exophytic tumor at the lateral oral tongue is illustrated. In group 2, white irregular areas represent residual carcinoma at the margin. In groups 2 and 3, colored dots represent tumor bed margins.

In group 1, tumor bed margins were not sampled, and all margins were obtained from the glossectomy specimen only. This scenario represents an en bloc glossectomy with clinically and/or pathologically satisfactory margins as determined by surgeons or pathologists at the time of surgery.

In group 2, the glossectomy specimen was examined by a pathologist, found to be positive or otherwise suboptimal (ie, distorted, ulcerated, or lacking normal mucosa at the mucosal margin), and the surgeon revised the margins by obtaining additional tissue from the tumor bed (revision group). The intent to revise was reflected in the labeling of tumor bed margins; such margins were frequently labeled as additional, new, revised, #2, or re-resection. In Figure 1, column 2, the white irregular areas on the anterior aspect of the glossectomy specimen represent residual carcinoma at the initial anterior margin (third row). Red (erythematous) mucosa behind the tumor at the posterior aspect of the glossectomy illustrates the second positive margin (third row). The anterior and posterior margins are revised by obtaining an additional anterior margin (red dot) and posterior margin (yellow dot) from the tumor bed (fourth row). To imagine the relationship between the actual glossectomy margins and additional tissue, the 2 types of margins are superimposed in the fifth row. Owing to the challenges of relocating the exact aspect of the relevant anterior margin in the tumor bed, size discrepancy, and uncertain orientation of the additional tissue, it is conceivable that, in some patients, the additional margin may not actually cover the entire residual tumor at the positive (anterior in the illustrated case) glossectomy margin.

In group 3, margins were primarily sampled from the tumor bed. In Figure 1, column 3, five margins are primarily sampled from the tumor bed (red, green, yellow, blue, and black dots), without preceding examination of the glossectomy specimen (displayed in lighter colors in the third row) by the pathologist.

Statistical Analysis

Local recurrence, the primary endpoint of this study, was measured as time from the date of surgery to the biopsy-proved recurrent SCC at the site of the prior glossectomy. A regional recurrence (or late metastasis) was defined as SCC in the regional lymph nodes of the neck.17 A second primary carcinoma was defined as SCC developing 4 years after the initial diagnosis at the site of the prior glossectomy or SCC at another site any time after the treatment of the index SCC. Patients were censored on the date of diagnosis of a regional recurrence, second primary carcinoma, death from other causes, or on the date of their last follow-up if they were free of LR at that time.

Differences among the 3 margin sampling groups were analyzed with Fisher exact test for categorical data (ie, sex) and a Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous data (ie, distance to margin). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the probability of LR-free survival, and the log-rank test was used to compare survival functions. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

Results

Among the 5 participating institutions, 280 patients were included for analysis. Patients were categorized according to the margin sampling approach. Overall, 119, 61, and 100 patients were placed into workflow groups 1, 2, or 3, respectively. Clinical and pathologic characteristics are detailed in the Table.

Table.

Patient Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Valuea | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1/Glossectomy Margin Group (n = 119) | Group 2/Revision Group (n = 61) | Group 3/Tumor Bed Margin Group (n = 100) | ||

| Age, median, y | 58.8 | 56.9 | 56.4 | .41 |

| Sexb | .07 | |||

| Men | 74 of 116 (63.8) | 27 of 59 (45.8) | 54 of 97 (55.7) | |

| Women | 42 of 116 (36.2) | 32 of 59 (54.2) | 43 of 97 (44.3) | |

| pT | .07 | |||

| T1 | 83 (69.7) | 33 (54.1) | 58 (58.0) | |

| T2 | 36 (30.3) | 28 (45.9) | 42 (42.0) | |

| Smoking statusc | .94 | |||

| Ever | 52 of 87 (59.8) | 33 of 54 (61.1) | 58 of 93 (62.4) | |

| Never | 35 of 87 (40.2) | 21 of 54 (38.9) | 35 of 93 (37.6) | |

| Alcohol statusd | .41 | |||

| Ever | 55 of 86 (64.0) | 38 of 52 (73.1) | 57 of 91 (62.6) | |

| Never | 31 of 86 (36.0) | 14 of 52 (26.9) | 34 of 91 (37.4) | |

| Largest tumor size, median, mm | 17 | 15 | 19 | .38 |

| Presence of intrinsic tongue musculature involvement | 103 (86.6) | 54 (88.5) | 92 (92.0) | .44 |

| Distance to closest margin (including cases with positive margins), median, mm | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | <.001e |

| Positive tumor bed margin | NA | 6 (9.8) | 7 (7.0) | .56 |

| Positive glossectomy margine | 9 of 117 (7.7) | 28 (45.9) | 23 of 95 (24.2) | <.001e |

| Differentiationf | .09 | |||

| Well | 11 of 116 (9.5) | 7 of 59 (11.9) | 5 of 99 (5.1) | |

| Moderate | 89 of 116 (76.7) | 50 of 59 (84.7) | 86 of 99 (86.9) | |

| Poor | 16 of 116 (13.8) | 2 of 59 (3.4) | 8 of 99 (8.1) | |

| Presence of PNI | 28 (23.5) | 23 (37.7) | 33 (33.0) | .10 |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 23 (19.3) | 14 (23.0) | 16 (16.0) | .54 |

Abbreviations: Differentiation, differentiation of squamous cell carcinoma; NA, not applicable; PNI, perineural invasion' pT, pathology T (tumor) stage.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Sex was not available in 8 patients.

Smoking history was unknown for 46 patients.

Alcohol history was unknown for 51 patients.

Glossectomy margin status was unknown for 7 patients.

Tumor differentiation was undetermined in 6 patients.

Most patients had no evidence of disease at their last follow-up visit (192 of 280 [68.6%]). Forty-two patients (15.0%) developed an LR, while 21(7.5%) developed a regional recurrence. Second primary cancers were identified in 25 patients (8.9%).

Thirty-three patients (11.8%) died as a result of their disease, while 38 (13.6%) died of other causes. Of the 33 patients who died of their disease, 13 had regional recurrences and 7 died after developing a second primary carcinoma.

Patients' median age, sex, tumor size and pT, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and frequency of adjuvant radiation were similar across the 3 workflow groups (Table). Three parameters were statistically significantly different among the patients in the 3 groups: frequency of positive glossectomy margins, distance from the invasive tumor front to the margin, and use of intraoperative consultation. The first 2 parameters were determined from the glossectomy specimen.

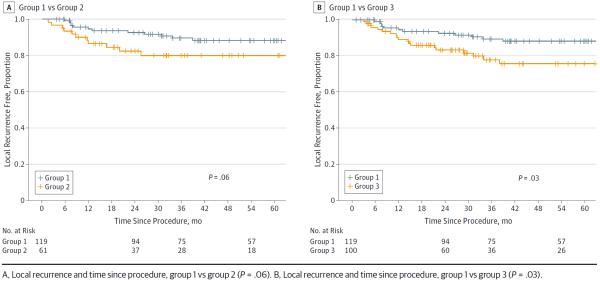

The frequency of positive glossectomy margins was lowest in group 1 (9 of 117 [7.7%]) compared with groups 2 (28 of 61 [45.9%]) and 3 (23 of 95 [24.2%]; P < .001). Distance from the invasive tumor front to the margin was narrowest in group 2 (0.5 mm) compared with groups 1 (3 mm) and 3 (1 mm) (P < .001). Even after excluding patients with positive margins, the distance from the invasive tumor front to the closest margin was significantly narrower in group 3 (2 mm) vs group 1 (3 mm) (P = .008) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Box Plot Distribution of Margin Clearance by Workflow Group

Intraoperative consultation was performed in 234 of 280 patients (83.6%) and was more frequent in groups 2 (55 of 58 [94.8%]) and 3 (93 of 100 [93.0%]) compared with group 1 (83 of 119 [69.7%]; P < .001). For 3 patients without intraoperative consultation, if margin revision was performed, it was done as a second procedure.

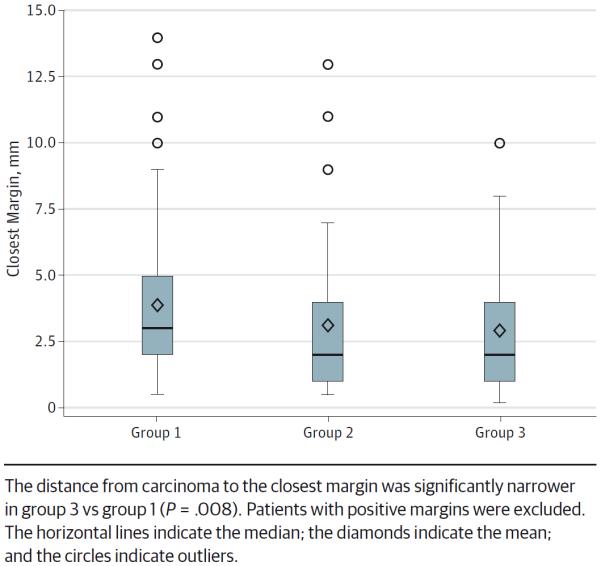

Workflow Groups and LR or Progression

The difference in LR-free survival at 3 years between groups 1 and 2 was not significantly different (0.9 vs 0.8; P = .06) (Figure 3A). However, the 3-year LR-free survival was worse for group 3 compared with that in group 1 (0.8 vs 0.9, respectively; P = .03) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Risk of Local Recurrence by Workflow Group

Comparing Tumor Bed Margins and Glossectomy Margins

The status (positive vs negative) of tumor bed margins and glossectomy margins was available for 95 patients in group 3. While 23 patients (24.2%) had positive glossectomy margins, only 7 patients (7.4%) had positive tumor bed margins. In other words, of the 23 patients with positive glossectomy margins, only 7 had positive tumor bed margins. If margins obtained from the glossectomy specimen are considered as the criterion standard, then the tumor bed margin was 24% sensitive (95% CI, 16%-34%) and 92% specific (95% CI, 85%-97%) for detecting a positive margin.

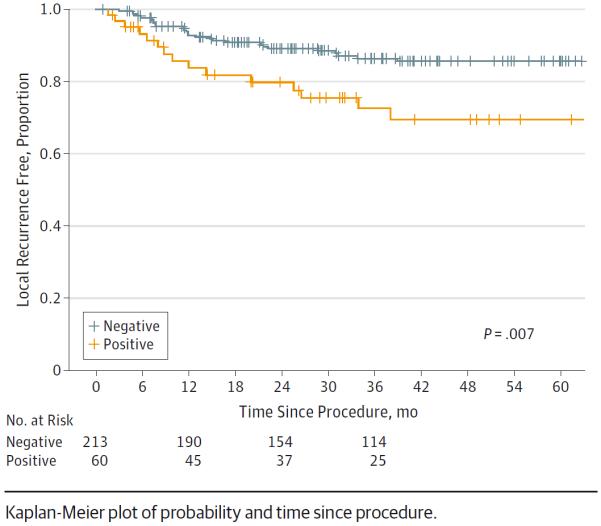

Prognostic Value of Margins

Glossectomy margin status (positive vs negative) significantly correlated with LR-free survival. At 3 years, patients with positive glossectomy margins had worse LR-free survival compared with patients with negative glossectomy margins (0.86 vs 0.73, respectively; P = .007) (Figure 4). Conversely, the status of the tumor bed margins was of no prognostic value in regard to LR-free survival.

Figure 4.

Risk of Local Recurrence by Status (Positive vs Negative) of the Glossectomy Margin

Discussion

En bloc resection, the mainstay of oncologic surgery, is still considered the standard of care. Among other potential benefits, en bloc resection facilitates confident histopathologic assessment of the adequacy of tumor resection in that pathologists have to examine only 1 oriented specimen with 1 set of margins. While most studies agree on the value of clear margins and adequate initial resection, the definition of a “true” margin becomes increasingly uncertain.

In areas aside from the head and neck, piecemeal tumor removal is often performed owing to anatomical constraints and the rise in tissue-conserving surgical procedures. This shift in oncologic management has led to the sampling of additional, presumably true, margins that are claimed to supersede the margins obtained from the en bloc resection specimen, such as retrotrigonal and basal margins after a prostatectomy.18 Such practices are actively debated in most subspecialties of surgical oncology and have led to subspecialized terminology, such as cavity shaved margins for breast surgery.5–8

Since the AHNS developed quality measures for head and neck cancer care, emphasis has been placed on compliance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.10,19 However, the controversial coexistence of 2 types of margins—those from the tumor bed and those from the resected specimen—was not addressed. A 2005 survey of 476 AHNS members demonstrated the variability of margin sampling.11 It was shown that 40% to 76% of surgeons obtained margins from the tumor bed.11,12 Most pathologists would still report on the status of margins from the resected specimen.12 In a significant number of patients, the status of the 2 types of margins will be discrepant. Then, the question is: which margin should surgeons and oncologists rely on when the tumor bed margin is negative but the glossectomy margin is positive?

Our current study aims to answer that question by determining whether the margin sampling technique correlates with local control. Rather than assuming that local control correlates only with margin status, we began by investigating whether local control depends on the surgical approach to margin sampling. To account for other confounding factors, such as tumor site, size, and lymph node status, we focused on pT1-2 pN0 SCC involving only the oral tongue.

We show that margin sampling from the tumor bed (group 3) was associated with worse local control. In fact, the preoperative decision to sample several margins from the tumor bed is one of just 2 prognostically relevant factors in this homogeneous cohort of patients.

The worse local control in group 3 may be caused by more frequent positive glossectomy margins and narrower margin clearance as measured on the glossectomy specimen. Clinically, the most confusing cases have a negative tumor bed margin and a positive glossectomy margin, which occurred in 16 patients in group 3. If surgeons and oncologists accept the tumor bed margin as a true margin, those 16 patients may have been undertreated. The rate of adjuvant radiation therapy was similar among all groups despite the significantly higher rate of positive glossectomy margins in group 3.

The low sensitivity of tumor bed margins for identifying positive glossectomy margins (24%) is consistent with findings outside of the head and neck. Other investigators have reported low sensitivity of tumor bed biopsies in partial nephrectomies.6

Tumor bed margins were obtained in 2 scenarios: from necessity (ie, group 2 [revision group in this study]) or based on preoperative planning and preference (group 3). For head and neck SCC, there appears to be a consensus that margin revision, as performed currently, is of little therapeutic value.13,20–24 Therefore, our finding that group 2 trended toward worse local control is consistent with prior reports. The limitations of the current approach to margin revision have previously been discussed.13 For instance, it is difficult to return to the tumor bed and to re-resect the exact portion of tissue correlating to the particular positive margin. In fact, investigators have demonstrated that surgeons are off target by approximately 1 cm in one-third of relocalization attempts.25

Why should the margin obtained from the glossectomy specimen remain a criterion standard? The status (positive vs negative) of the glossectomy margin correlated with LR-free survival and was the only histologic parameter to do so. Conversely, we show here the falsely reassuring nature of tumor bed margins, which have a low sensitivity for a positive glossectomy margin and, by definition, cannot identify close margins. Some of these findings were reported previously in the head and neck and other anatomical areas.6,13,26,27

This study is focused on patients who, ideally, are cured by surgery alone. The multi-institutional retrospective study of margins in patients with pT1-2 carcinomas was made possible by a uniform sampling approach; most specimens and tumors are small enough to be entirely submitted for microscopic examination. By design, other sites, especially those that may require sampling of bony margins, were avoided. It is therefore unclear how to extrapolate our findings to more anatomically complex subsites or to larger, more advanced carcinomas.

Conclusions

The margin obtained from the en bloc glossectomy specimen remains the only prognostically relevant margin. The surgical method of margin sampling affected local control; reliance on tumor bed margins was associated with worse local control, which is most likely caused by narrower margin clearance and a greater number of positive glossectomy margins. Given the low sensitivity of tumor bed margins for identifying positive margins on the resected specimen, relying on tumor bed margins for adjuvant therapy selection may lead to undertreatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This project used the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Biostatistics Facility that is supported in part by award P30CA047904.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Chiosea had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs Maxwell and Thompson contributed equally.

Study concept and design: Thompson, Duvvuri, Johnson, Ferris, Seethala, Chiosea.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Maxwell, Thompson, Brandwein-Gensler, Weiss, Canis, Purgina, Prabhu, Lai, Shuai, Carroll, Morlandt, Kim, Johnson, Ferris, Seethala, Chiosea.

Drafting of the manuscript: Maxwell, Thompson, Brandwein-Gensler, Shuai, Chiosea.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Maxwell, Thompson, Brandwein-Gensler, Weiss, Canis, Purgina, Prabhu, Lai, Carroll, Morlandt, Duvvuri, Kim, Johnson, Ferris, Seethala, Chiosea.

Statistical analysis: Prabhu, Shuai, Chiosea.

Obtained funding: Duvvuri.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Maxwell, Canis, Purgina, Lai, Morlandt, Duvvuri, Kim, Chiosea.

Study supervision: Thompson, Carroll, Duvvuri, Johnson, Ferris, Seethala, Chiosea.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This work does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Previous Presentation: This study was presented as a poster at the Annual Meeting of the American Head and Neck Society; April 23, 2015; Boston, Massachusetts.

Additional Contributions: Robyn Roche, Department of Pathology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, provided administrative assistance; she was not compensated for her contribution. Laura Sesto, a private contractor, provided medical illustrations; she was compensated for her contribution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ishihara R, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial Barrett's esophageal cancer in the Japanese state and perspective. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2(3):24. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.02.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamzany Y, Brasnu D, Shpitzer T, Shvero J. Assessment of margins in transoral laser and robotic surgery. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2014;5(2):e0016. doi: 10.5041/RMMJ.10150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wellman BJ, Traynelis VC, McCulloch TM, Funk GF, Menezes AH, Hoffman HT. Midline anterior craniofacial approach for malignancy: results of en bloc versus piecemeal resections. Skull Base Surg. 1999;9(1):41–46. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1058171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steiner W. Results of curative laser microsurgery of laryngeal carcinomas. Am J Otolaryngol. 1993;14(2):116–121. doi: 10.1016/0196-0709(93)90050-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emiliozzi P, Amini M, Pansadoro A, Martini M, Pansadoro V. Intraoperative frozen section in laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: impact on cancer control. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2010;82(4):164–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagemann IS, Lewis JS., Jr A retrospective comparison of 2 methods of intraoperative margin evaluation during partial nephrectomy. J Urol. 2009;181(2):500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coopey SB, Buckley JM, Smith BL, Hughes KS, Gadd MA, Specht MC. Lumpectomy cavity shaved margins do not impact re-excision rates in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(11):3036–3040. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singletary SE. Surgical margins in patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast conservation therapy. Am J Surg. 2002;184(5):383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinni ML, Ferlito A, Brandwein-Gensler MS, et al. Surgical margins in head and neck cancer: a contemporary review. Head Neck. 2013;35(9):1362–1370. doi: 10.1002/hed.23110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen AY. Quality initiatives in head and neck cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12(2):109–114. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier JD, Oliver DA, Varvares MA. Surgical margin determination in head and neck oncology: current clinical practice: the results of an International American Head and Neck Society member survey. Head Neck. 2005;27(11):952–958. doi: 10.1002/hed.20269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black C, Marotti J, Zarovnaya E, Paydarfar J. Critical evaluation of frozen section margins in head and neck cancer resections. Cancer. 2006;107(12):2792–2800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang AM, Kim SW, Duvvuri U, et al. Early squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue: comparing margins obtained from the glossectomy specimen to margins from the tumor bed. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(11):1077–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Bai S, Carroll W, et al. Validation of the risk model: high-risk classification and tumor pattern of invasion predict outcome for patients with low-stage oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(3):211–223. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0412-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canis M, Ihler F, Martin A, Wolff HA, Matthias C, Steiner W. Enoral laser microsurgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Head Neck. 2014;36(6):787–794. doi: 10.1002/hed.23365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook: From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed Springer; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duvvuri U, Seethala RR, Chiosea S. Margin assessment in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2014;120(3):452–453. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valotto C, Falconieri G, Pizzolitto S, et al. Residual prostatic tumour in the surgical bed following radical prostatectomy in organ-confined prostate cancer: possible prognostic significance. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2011;83(2):78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hessel AC, Moreno MA, Hanna EY, et al. Compliance with quality assurance measures in patients treated for early oral tongue cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(14):3408–3416. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillemaud JP, Patel RS, Goldstein DP, Higgins KM, Enepekides DJ. Prognostic impact of intraoperative microscopic cut-through on frozen section in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;39(4):370–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jäckel MC, Ambrosch P, Martin A, Steiner W. Impact of re-resection for inadequate margins on the prognosis of upper aerodigestive tract cancer treated by laser microsurgery. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(2):350–356. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000251165.48830.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwok P, Gleich O, Hübner G, Strutz J. Prognostic importance of “clear versus revised margins” in oral and pharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2010;32(11):1479–1484. doi: 10.1002/hed.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel RS, Goldstein DP, Guillemaud J, et al. Impact of positive frozen section microscopic tumor cut-through revised to negative on oral carcinoma control and survival rates. Head Neck. 2010;32(11):1444–1451. doi: 10.1002/hed.21334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholl P, Byers RM, Batsakis JG, Wolf P, Santini H. Microscopic cut-through of cancer in the surgical treatment of squamous carcinoma of the tongue: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Am J Surg. 1986;152(4):354–360. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerawala CJ, Ong TK. Relocating the site of frozen sections—is there room for improvement? Head Neck. 2001;23(3):230–232. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200103)23:3<230::aid-hed1023>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiNardo LJ, Lin J, Karageorge LS, Powers CN. Accuracy, utility, and cost of frozen section margins in head and neck cancer surgery. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(10, pt 1):1773–1776. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200010000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yahalom R, Dobriyan A, Vered M, Talmi YP, Teicher S, Bedrin L. A prospective study of surgical margin status in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a preliminary report. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98(8):572–578. doi: 10.1002/jso.21034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]