Abstract

Aim

The drugs of choice in the treatment of urticaria in children are H1-antihistamines. The aim of the study was to evaluate children with urticaria and define risk factors for requirement of high-dose H1-antihistamines in children with urticaria.

Material and Methods

The medical data of children who were diagnosed as having urticaria admitted to our outpatient clinic between January 2014 and January 2016 were searched. The medical histories, concomitant atopic diseases, parental atopy histories, medications, treatment responses, blood eosinophil and basophil counts, and serum total IgE levels were recorded. In addition, the urticaria activity score for seven days, autoimmune antibody tests, and skin prick test results were evaluated in children with chronic urticaria.

Results

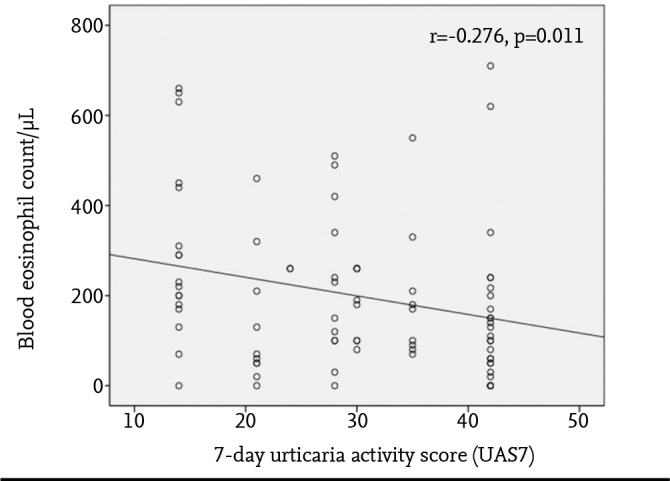

The numbers of the children with acute and chronic urticaria were 138 and 92, respectively. The age of the children with chronic urticaria was higher than that of those with acute urticaria (p<0.0001). There was no difference between the two groups in terms of blood eosinophil and basophil counts, and serum total IgE levels (p>0.05). There was a negative correlation between blood eosinophil count and the UAS7 score in children with chronic urticaria (r=−0.276, p=0.011). Chronic urticaria and requirement of high dose H1-antihistamines were significant in children aged ≥10 years (p<0.001, p=0.015). High UAS7 score (OR: 1.09; CI 95%: [1.03–1.15]) and basopenia (OR: 6.77; CI 95%: [2.01–22.75]) were associated with the requirement of high-dose H1-AH in children with chronic urticaria.

Conclusion

The requirement of high-dose H1-antihistamines was higher with children’s increasing age. Disease severity and basopenia were risk factors for the requirement of high-dose H1-antihistamines.

Keywords: Acute urticaria, antihistamine, chronic urticaria, pediatrics, treatment, urticaria

Introduction

Urticaria is defined as suddenly-occurring raised and itchy bumps that shift during the day. Urticaria is divided into two subtypes as acute and chronic urticaria. Approximately 20% of children have at least one urticaria episode during their lifetime (1). Chronic urticaria is observed substantially rarely in childhood. The incidence of chronic urticaria ranges between 0.1% and 3% (2).

Symptoms regress in a time period shorter than six weeks in acute urticaria, but this time period is ≥6 weeks in chronic urticaria (3). Chronic urticaria is mainly classified as chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), physical urticaria (PU), and other urticaria types. CSU constitutes the majority of chronic urticaria (1–3). Chronic spontaneous urticaria is defined as urticaria that occurs without the presence of any triggering factor. Chronic autoimmune urticaria (CAU) is observed in 40–45% of children with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Autoantibodies against high-affinity immunoglobulin (Ig) E receptors and autoreactive functional IgG antibodies against IgE antibodies are present in chronic autoimmune urticaria (1). The diagnosis of chronic autoimmune urticaria is made using the basophil histamine release or basophil activation tests (4). Physical urticaria is classified as late pressure urticaria, cold urticaria, heat contact urticaria, urticaria factitia and vibratory urticaria. Other urticaria types include cholinergic urticaria, water-induced urticaria, contact urticaria, and exercise-induced anaphylaxis/urticaria (1).

The approach to urticaria should include a comprehensive assessment. Urticaria may be triggered by infection, atopy, drugs, food, food additives, and autoimmune diseases. It has been reported that the risk of chronic urticaria increases in individuals who have had multiple acute urticaria episodes. However, the differences in the mechanisms of these two diseases, which appear to be similar to each other, have not yet been elucidated fully (5).

According to guidelines prepared in accordance with data obtained mostly in adult studies, the primarily preferred drug in acute and chronic urticaria exacerbations in children is second-generation H1-antagonists (H1-AH). If success of therapy cannot be achieved with H1AH used at the usual dose, high-dose H1-AH is recommended (1, 3, 6–9). It has been reported that corticosteroids may be used short-term (up to ten days) in periods of urticaria exacerbations. However, guidelines also state that a definite recommendation cannot be made, because there are insufficient randomized controlled studies in this area (1, 3, 9).

The primary treatment option in long-term treatment of chronic urticaria is again second-generation non-sedative H1-AH. Guidelines recommend that the dose should be increased three- or four-fold in cases where response to H1-AH treatment is not obtained at normal doses (1, 3, 9). However, the number of randomized controlled studies is substantially low for evidence-based recommendations in children. In patients who do not respond to high-dose H1-antihistaminic treatment, corticosteroid, omalizumab, cyclosporin A, and montelukast constitute tertiary treatment option. However, these drugs are recommended only in eligible patients because of the adverse effects and costs of these drugs (9).

Although urticaria is extremely common in childhood, our information related with factors that affect H1-AH treatment response is considerably limited. In this study, we examined the demographic and clinical properties, laboratory values, and H1-AH treatment responses of patients who presented to our outpatient clinic during the last two years and who were diagnosed as having urticaria, and aimed to determine risk factors that necessitate high-dose H1-AH treatment.

Material and Methods

The file data of patients who presented to our outpatient clinic between January 2014 and January 2016 were evaluated. All patients with a diagnosis code of urticaria (ICD10, L-50) were included in the study. All patients were diagnosed using the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO urticaria diagnosis criteria (1). Patients who were evaluated to have anaphylaxis, food allergy, bee allergy, contact dermatitis or drug allergy, which may be accompanied by urticaria symptoms, were not included in the study. A new generation non-sedative H1-antihistaminic drug was initiated at the standard dose according to the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO urticaria treatment guideline recommendations (9). With this objective, desloratadin was initiated at a dose of 2.5 mL (1.25mg) in children aged between 2 and 6 years, at a dose of 5 mL (2.5 mg) in children aged between 6 and 12 years, and at a dose of 5 mg (one tablet) in children aged more than 12 years, and the dose was increased three-fold in patients in whom a treatment response could not be obtained. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of Adnan Menderes University Medical Faculty (2016/865).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses of the study were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). The analysis of normal distribution of the continuous variables was performed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and homogeneity was analyzed using the homogeneity test of variance. Diagnostic statistical data were defined as median and (25th–75th percentile) values. The frequency of the data was specified with frequency analysis and shown as percentage (%). The Chi-square test was used for dual and multiple comparisons of independent categorical data. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparisons between independent numerical variables that did not have normal distribution. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used for correlation analyses. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The files of 9 200 patients who presented to the outpatient clinic of our hospital were reviewed and 230 patients who were diagnosed as having urticaria were included in the study. The demographic properties and laboratory values of the patients with urticaria are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic charcteristics and laboratory data of the children with urticaria

| Demographic properties (N=230) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (%) | |

| Female/Male | 112/118 |

| Age (years) | |

| Median (25–75 p.) | 7 (4–13) |

| Type of urticaria | |

| Acute | 138 (60%) |

| Chronic | 92 (40%) |

| Chronic spontaneous urticaria | 64 (27.8%) |

| Chronic autoimmune urticaria | 7/15 (46.6%) |

| Physical urticaria | 19 (8.3%) |

| Urticaria factitia | 11 (4.8%) |

| Cholinergic | 6 (2.6%) |

| Other | |

| Cold urticaria | 2 (0.9%) |

| Familial history of atopy (%) | 43 (18.7%) |

| Asthma | 11 (4.8%) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 21 (9.1%) |

| Association of asthma and allergic Rhinitis | 4 (1.7%) |

| Drug allergy | 5 (2.1%) |

| Urticaria | 2 (0.9%) |

| Personal history of atopy (%) | 57 (24.8%) |

| Asthma | 31(13.5%) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 15 (6.5%) |

| Drug allergy | 3 (1.3%) |

| Other | 8 (0.8%) |

| Triggering factors (%) | |

| Acute infection | 86 (37.4%) |

| Food | 26 (11.3%) |

| Drug | 34 (14.8%) |

| Parasite | 14 (6%) |

| Unknown | 70 (30.5%) |

| 7-Day Urticaria activity score (UAS7) | |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 30 (21–42) |

| Treatment | |

| H1-AH | 173 (75.2%) |

| High-dose H1-AH | 53 (23%) |

| Anti-IgE | 4 (1.7%) |

| Laboratory | |

| Eosinophil count/μL | |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 170 (80–320) |

| Basophil number/μL | |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 20 (20–40) |

| Serum total IgE (IU/mL) | |

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 71 (22–167) |

H1-AH: H1 antihistamines

Acute urticaria was found in 138 (60%) of patients, and chronic urticaria was found in 92. The comparison of the demographic properties and laboratory values of the patients with acute and chronic urticaria is shown in Table 2. The age and need for high-dose H1-AH were found higher in patients with chronic urticaria compared with patients with acute urticaria (p<0.001, p<0.001, respectively). The basophil histamine release test was performed in 15 patients with chronic urticaria. A diagnosis of CAU was made in seven (46.7%) of these patients. The basophil histamine release test could not be performed in the other patients with chronic urticaria, because this test was being performed abroad and had a high cost.

Table 2.

Comparison of the demographic properties and laboratory data of the children with acute and chronic urticaria

| Demographic properties | Acute Urticaria (n=138) | Chronic Urticaria (n=92) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (%) | |||

| Female/Male | 63/75 | 49/43 | 0.258 |

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 7 (4–11) | 10.5 (6–14.75) | <0.001 |

| Familial history of atopy (%) | |||

| Yes/No | 17/121 | 26/66 | 0.002 |

| Personal history of atopy (%) | |||

| Yes/No | 34/104 | 23/69 | 0.95 |

| Triggering factors | |||

| Acute infection | 67 (48.5%) | 19 (20.6%) | |

| Food | 16 (11.6%) | 10 (10.9%) | |

| Drug | 12 (8.7%) | 22 (23.9%) | 0.006 |

| Insect/Parasite | 14 (10.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unknown | 29 (21%) | 41 (44.6%) | |

| Treatment (%) | |||

| H1-AH response (+) | 116 (84.1%) | 57 (62%) | |

| H1-AH response (−) | 22 (15.9%) | 35 (38%) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory | |||

| Eosinophil count/μL | |||

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 155 (87.5–342.5) | 180 (80–290) | 0.717 |

| Basophil count/μL | |||

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 20 (20–40) | 30 (12.5–40) | 0.792 |

| Serum total IgE (IU/mL) | |||

| Median (25th–75th percentile) | 60 (19.7–163.5) | 87 (28.4–173) | 0.17 |

H1-AH: H1 antihistamines

Acute infections and contact with insects/presence of parasites were observed more frequently in children with acute urticaria, and familial history of atopy and development of urticaria following drug intake were observed more frequently in patients with chronic urticaria (p<0.05) (Table 2). The infections included acute upper respiratory tract infection (66%), urinary tract infection (22%), acute gastroenteritis (7%) and others (5%). The drugs that caused urticaria frequently included antibiotics with a beta-lactam ring (64%), non-steroid analgesic drugs (21%), and other drugs (15%). Eosinophilia (>400/μL) was found in 43 patients and basopenia (<20μL) was found in 55 (23.9%). Serum total IgE levels were measured in a total of 176 patients and were found increased (>100 IU/mL) in 67 of these patients (38%). Antithyroid antibodies (anti-thyroglobulin and anti-peroxidase), antinuclear antibody level, parasite in stool, complete urinalysis, and urinary cultures were studied in all patients with chronic urticaria. Hashimoto thyroiditis was found in four patients (4.3%) and parasitic infection was found in two patients (2.2%).

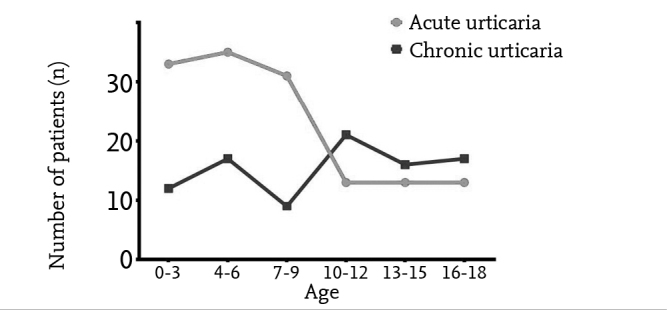

When variance of the frequency of urticaria by age was examined, it was observed that acute urticaria was more frequent between the ages of 0 and 9 years, and it decreased markedly after the age of 9 years (Figure 1). Chronic urticaria tended to increase slightly after the age of ten years. A marked difference was found between children aged <10 years and children aged ≥10 years in terms of the frequency of acute and chronic urticaria (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Course of the frequency of acute and chronic urticaria by ages

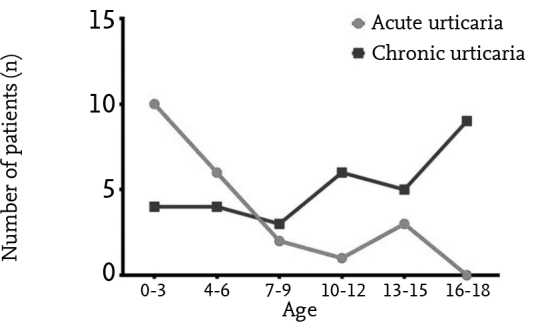

High-dose H1-AH treatment was initiated in 22 (15.9%) patients with acute urticaria and in 35 (38%) patients with 200 chronic urticaria. A diagnosis of severe acute urticaria was made in 31 (22.5%) patients with acute urticaria and short-term oral corticosteroid treatment was initiated in addition to high-dose H1-AH treatment. Montelukast was added to treatment in 14 (15.2%) patients with chronic urticaria, because a sufficient response could not be obtained with high-dose H1-AH treatment. However, no improvement in clinical findings was observed in any patients. Anti-IgE (Omalizumab) at a dose of 300 mg was administered for 12 months in four (4.3%) of these patients. The symptoms improved in all patients from the first dose of treatment. The symptoms did not recur during the first year of follow-up following discontinuance of treatment in three patients. Symptoms recurred three months after anti-IgE treatment was discontinued in only one patient who had CAU and anti-IgE treatment was initiated again. Presence of atopy was not found to have an effect on treatment response in children with chronic urticaria (p>0.05). When the frequency of absence of response to normal dose H1-AH was examined by age, it was observed that high-dose H1-AH was required mostly at earlier ages in children with acute urticaria and at older ages in children with chronic urticaria. High-dose H1-AH was required more frequently in children aged ≥10 years compared with children aged <10 years (p=0.015). The distribution of children who required high-dose H1-AH by ages is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The frequency by ages in the children with acute and chronic urticaria who required high-dose H1-antihistaminic treatment

The UAS7 score was found as 30 (21–42) in patients with chronic urticaria. A negative correlation was found between blood eosinophil number and UAS7 in children who had chronic urticaria (r=−0.276, p=0.011) (Figure 3). In the children who had chronic urticaria, severity of urticaria (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: [1.03–1.15]) and basopenia (OR: 6.77; 95% CI: [2.01–22.75]) were found correlated with the need for high-dose H1-AH.

Figure 3.

Correlation between the blood eosinophil count and seven day-urticaria activity score (UAS7) in children with chronic urticaria

Discussion

Although urticaria is observed extremely frequently in the childhood, its pathogenesis has not yet been elucidated fully. A limited number of studies have investigated the clinical properties and antihistaminic treatment responses of children with urticaria in the literature. In this study, we reported our experience of 230 children with urticaria who were followed up in the last two years in our tertiary care center. In addition to presenting the demographic and clinical characteristics of our patients, we attempted to specify risk factors that affect the requirement for high-dose H1-AH for the first time in the literature.

In our study, no significant difference was found between children with acute urticaria and children with chronic urticaria in terms of sex. Similarly, no significant difference was found in terms of sex in children with acute and chronic urticaria by Chang et al. (10), in children with acute urticaria who presented to emergency department by Liu et al. (11), or in children with food-induced urticaria by Wananukul et al. (12). However, urticaria is observed more frequently in adult women compared with adult men (3). This suggests that hormones may have an impact on the development of urticaria (3). As Chang et al. (10) proposed in their study, we also think that sex has no impact on urticaria, because the mean age of our patients corresponded to the period before adolescence.

In our study, the mean age of children with acute urticaria was significantly lower compared with children who had chronic urticaria. Acute urticaria was observed more frequently in children aged below ten years and chronic urticaria was observed more frequently in children aged 10 years and older. In the literature, the age range is 3–8 years for acute urticaria and 8.8–10.4 years for chronic urticaria in childhood (10, 11, 13–15). The main reasons for the age difference between the two diseases may include triggering of acute urticaria, mostly by external factors; a shorter time period required for occurrence of symptoms in acute urticaria; development of chronic urticaria over a longer time period; and presence of autoimmune mechanisms in chronic urticaria.

The success of specifying triggering factors in urticaria ranges between 21% and 83% in different studies (10–16). In our study, we found no factors that could lead to urticaria in approximately one fifth of the children with acute urticaria, and in approximately half of the children with chronic urticaria.

The most common etiologic factors in children with acute urticaria include acute infections, food, insect bites, and parasitic infections, respectively (11, 14, 17–19). In our study, the triggering factors we found were similar to those in many studies in the literature. The rate of specifying the triggering factors in urticaria ranges between 12.4% and 17% in different studies (11, 19, 20). It is very difficult to differentiate etiologic factors in urticaria that occurs after use of medication during acute infection in children. It is thought that the reaction frequently arises from infectious agents or the interaction between medication and infectious agents (21). It is difficult to establish a cause-effect relationship between urticaria and drug allergy in patients who present to the emergency department, because further tests are needed for a diagnosis of drug allergy (22). We think our rates were lower compared with other studies, because the actual drug reactions were found later by performing the necessary diagnostic tests for drug allergy in all patients who presented to our outpatient clinic.

The basophil histamine release test was performed in only 15 patients who were diagnosed with chronic urticaria in our study, and a diagnosis of CAU was made in approximately half of these patients. Our results were found compatible with the frequencies of CAU reported in the literature (40% and 47%) (23, 24).

In our study, we found the blood eosinophil and basophil counts as low in children with urticaria. In addition, no difference was found between the blood eosinophil and basophil levels and total serum IgE levels in children with acute and chronic urticaria. In the study conducted by Chang et al. (10), no difference was found between children who had acute urticaria and the children who had chronic urticaria in terms of the blood eosinophil count and total IgE levels. Cell accumulation of eosinophils, basophils, neutrophils and lymphocytes in the skin due to migration may lead to a decrease in the numbers of the cells circulating in the blood (25). This may be the reason why an increase in blood eosinophil and basophil counts was not found.

In our study, autoimmune antibody tests were performed in all patients with chronic urticaria, and Hashimoto thyroiditis was found in only four patients. Caminiti et al. (26) reported four patients with Hashimoto thyroiditis out of 95 patients with chronic urticaria, similar to our results. Brunetti et al. (23) found no autoimmune diseases in any of 93 patients with chronic urticaria. In the other studies, the rate of increased anti-thyroid antibodies ranged between 1.1% and 4.3% (13, 27).

In our study, the need for high-dose H1-AH was found higher than our expectations in children with both acute and chronic urticaria. This may be related with the primary treatment preference of high-dose H1-AH instead of systemic corticosteroid in our outpatient clinic. We found no other studies in relation with this issue with which we could compare our data. The requirement for high-dose H1-AH was more frequent at the earlier ages in children with acute urticaria, whereas it started from age ten years in children with chronic urticaria and increased in years.

In addition, a diagnosis of severe acute urticaria was made only in one fifth of patients with acute urticaria in our study, and short-term oral corticosteroid treatment was initiated in addition to high-dose H1-AH treatment. Similarly, the rate of oral corticosteroid use was reported as 20% by Ricci et al. (14), the rate of intravenous corticosteroid use was reported as 27%, and oral corticosteroid use was reported as 18.9% by Liu et al. (11). Lee et al. (28) reported treatment unresponsiveness with normal dose H1-AH in 50% of patients in their study of 98 children with chronic urticaria. Urticaria symptom control was achieved with a two-fold higher H1-AH dose in 37.5% of these patients, a three-fold higher dose in 6.2%, and a four-fold higher dose in 5.3%. In addition, the risk factors related with H1-AH unresponsiveness were found as severity of urticaria and basopenia in our study. There are very few studies in this area in the literature. Only one study reported a relationship between the presence of familial history of atopy, angioedema, and drug allergy, and the need for high-dose H1-AH (28).

In conclusion, the differences between acute and chronic urticaria, the effect of the patient’s age on the type of urticaria and H1-AH treatment response, and the risk factors related with requirement for high-dose H1-AH treatment were reported in this study, in which we presented our single-center experience. We think that our data will be useful in assessment and follow-up of patients with urticaria in daily practice. Specifying H1-AH treatment response in advance in patients with urticaria is considerably important in terms of establishing more efficient treatment approaches in a shorter time. However, our results should be confirmed with prospective studies with larger patient series.

Acknowledgements

We thank to our nurse Nazmiye Özdemir for her contribution in evaluation of patient files.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Local ethics committee approval was received for this study from Adnan Menderes University School of Medicine (2016/865).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was not obtained because of the retrospective design of the study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - P.U., S. A.; Design - P.U., S.A.; Supervision - D. E.; Data Collection and/or Processing - P.U., S.A.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - P.U., S.A., D.E.; Literatüre Review - P.U., S.A.; Writing - P.U., S.A.; Critical Review - D.E.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization. The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014;69:868–87. doi: 10.1111/all.12313. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan AP. Clinical practice: chronic urticaria and angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:175–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp011186. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp011186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sánchez-Borges M, Asero R, Ansotegui IJ, et al. Scientific and Clinical Issues Council. Diagnosis and treatment of urticaria and angioedema: a worldwide perspective. World Allergy Organ J. 2012;5:125–47. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182758d6c. https://doi.org/10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182758d6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann HJ, Santos AF, Mayorga C, et al. The clinical utility of basophil activation testing in diagnosis and monitoring of allergic disease. Allergy. 2015;70:1393–405. doi: 10.1111/all.12698. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnaswamy G, Youngberg G. Acute and chronic urticaria: challenges and considerations for primary care physicians. Postgrad Med. 2001;109:107–8. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2001.02.861. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2001.02.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asero R. Chronic unremitting urticaria: is the use of antihistamines above the licensed dose effective? A preliminary study of cetirizine at licensed and above-licensed doses Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:34–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuberbier T, Iffländer J, Semmler C, Henz BM. Acute urticaria: clinical aspects and therapeutic responsiveness. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76:295–7. doi: 10.2340/0001555576295297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asero R, Tedeschi A. Usefulness of a short course of oral prednisone in antihistamine-resistant chronic urticaria: a retrospective analysis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010;20:386–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: management of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1427–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02178.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang KL, Yang YH, Yu HH, Lee JH, Wang LC, Chiang BL. Analysis of serum total IgE, specific IgE and eosinophils in children with acute and chronic urticaria. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2013;46:53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.12.030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu TH, Lin YR, Yang KC, Chou CC, Chang YJ, Wu HP. First attack of acute urticaria in pediatric emergency room. Pediatr Neonatol. 2008;49:58–64. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(08)60014-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1875-9572(08)60014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wananukul S, Chatproedprai S, Tempark T, Phuthongkamt W, Chatchatee P. The natural course of childhood atopic dermatitis: a retrospective cohort study. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2015;33:161–8. doi: 10.12932/AP0498.33.2.2015. https://doi.org/10.12932/ap0498.33.2.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jirapongsananuruk O, Pongpreuksa S, Sangacharoenkit P, Visitsunthorn N, Vichyanond P. Identification of the etiologies of chronic urticaria in children: a prospective study of 94 patients. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21:508–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00912.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricci G, Giannetti A, Belotti T, et al. Allergy is not the main trigger of urticaria in children referred to the emergency room. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1347–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03634.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas N, Birkle-Berlinger W, Henz BM. Prognosis of acute urticaria in children. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:74–5. doi: 10.1080/00015550410023545. https://doi.org/10.1080/00015550410023545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volonakis M, Katsarou-Katsari A, Stratigos J. Etiologic factors in childhood chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy. 1992;69:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu CC, Kuo HC, Yu HR, Wang L, Yang KD. Association of acute urticaria with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in hospitalized children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:134–9. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60166-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wedi B, Raap U, Wieczorek D, Kapp A. Urticaria and infections. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2009;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-5-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1710-1492-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sackesen C, Sekerel BE, Orhan F, Kocabas CN, Tuncer A, Adalioglu G. The etiology of different forms of urticaria in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:102–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0736-8046.2004.21202.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0736-8046.2004.21202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konstantinou GN1, Papadopoulos NG, Tavladaki T, Tsekoura T, Tsilimigaki A, Grattan CE. Childhood acute urticaria in northern and southern Europe shows a similar epidemiological pattern and significant meteorological influences. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:36–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01093.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanca M, Thong B. Progress in understanding hypersensitivity drug reactions: an overview. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:337–40. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328355b8f5. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACI.0b013e328355b8f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seitz CS, Brocker EB, Trautmann A. Diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity in children and adolescents: discrepancy between physician-based assessment and results of testing. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:405–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01134.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunetti L, Francavilla R, Miniello VL, et al. High prevalence of autoimmune urticaria in children with chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:922–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du Toit G, Prescott R, Lawrence P, et al. Autoantibodies to the high-affinity IgE receptor in children with chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;96:341–4. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61245-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vonakis BM, Saini SS. New concepts in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:709–16. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.09.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caminiti L, Passalacqua G, Magazzu G, et al. Chronic urticaria and associated coeliac disease in children: a case-control study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16:428–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00309.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahiner UM, Civelek E, Tuncer A, et al. Chronic urticaria: etiology and natural course in children. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;156:224–30. doi: 10.1159/000322349. https://doi.org/10.1159/000322349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee XHM, Ong LX, Cheong JYV, et al. A stepwise approach in the management of chronic spontaneous urticaria in children. Asia Pac Allergy. 2016;6:16–28. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2016.6.1.16. https://doi.org/10.5415/apallergy.2016.6.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]