Abstract

We have developed a novel aptamer-targeting photoresponsive drug delivery system by non-covalent assembly of a Cy5.5-AS1411 aptamer conjugate on the surface of graphene oxide wrapped doxorubicin (Dox)-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN-Dox@GO-Apt) for light-mediated drug release and aptamer-targeted cancer therapy. The two “off–on” switches of the MSN-Dox@GO-Apt were controlled by aptamer targeting and light triggering, respectively. The Cy5.5-AS1411 ligand provides MSN-Dox@GO-Apt with nucleolin specific targeting and real-time indicator abilities by “off–on” Cy5.5 fluorescence recovery. The GO acts as a gatekeeper to prevent the loaded Dox from leaking in the absence of laser irradiation, and to control the Dox release in response to laser irradiation. When the GO wrapping falls off upon laser irradiation, the “off–on” photoresponsive drug delivery system is activated, thus inducing chemotherapy. Interestingly, with an increase in laser power, the synergism of chemotherapy and photothermal therapy in a single MSN-Dox@GO-Apt platform led to much more effective cancer cell killing than monotherapies, providing a new approach for treatment against cancer.

Introduction

Photoresponsive drug delivery systems (PDDSs) have been developed for sophisticated controlled drug release to reduce the side effects of traditional chemotherapy on normal tissues and improve therapeutic efficacy in treating lesions.1–8 Typically, ultraviolet (UV), visible (Vis) or near-infrared (NIR) light is used as an exogenous stimuli to trigger drug release.2 However, UV or Vis light exhibits high toxicity to normal tissue or low penetration depth (~10 mm) due to the strong scattering ability of skin and soft tissues in this optical window.2,4 Therefore, the development of NIR-light triggered PDDSs allowing deeper penetration, lower scattering and minimal harm is highly desirable.9

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs), due to their large loading capacity, high thermal stability, good biocompatibility, and versatile chemistry for surface functionalization, have been employed as building blocks for PDDSs.10,11 For MSN-based PDDSs, light-sensitive gatekeepers are utilized to block the pores of the MSNs and prevent guest drugs from leaking. UV-Vis reversible photoisomerization of the azobenzene group (and its derivatives),12–14 UV spiropyran–merocyanine isomerization,15 and the photodimerization–cleavage cycle of thymine16 have been reported as intelligent switches for the opening and closing of the pore mouths of MSNs. However, most of these strategies are rather complicated and time-consuming. Meanwhile, the occupation of gatekeepers at important locations of the pore interior or mouth would jeopardize either drug loading or release efficiency.12 Therefore, it is desirable to find a better way to block the pores of the MSN-based PDDSs.

Graphene oxide (GO), a flexible 2-dimensional carbon nanosheet, has been widely used as the basic building block of hierarchical ensembles due to its light and heat sensitivity, as well as good biocompatibility and highly functional surface.17–19 GO can effectively transduce NIR light into heat, potentially acting as a photothermal switch for controlled drug release. GO also exhibits unique abilities such as DNA/RNA adsorption20,21 and excellent quenching of dye-labeled DNA/ RNA.22 Wang et al.22 used GO to deliver dye-labeled aptamer to demonstrate that GO can serve as a platform with high fluorescence quenching efficiency for targeted imaging in living cells. Recently, GO has been used to enwrap MSNs, gold nanoparticles and gold nanorods.23–25 Through appropriate wrapping, GO can act as a great gatekeeper for MSNs without occupying the pore interior or mouth. Zhao et al.23 reported a hybrid material using GO sheets to wrap squaraine dye-loaded MSNs to protect the dye molecules from nucleophilic attack. Therefore, GO can potentially play multiple roles in the construction and development of PDDSs.

In addition to sophisticated photoactivation properties, the active targeting function of PDDSs is also very important in the delivery of drugs/agents to specific disease sites or cell populations such as tumor cells. Aptamers, a class of artificial DNA/RNA probes, have attracted much attention in the engineering of target platforms.26 They have significant advantages over antibodies, such as flexible design, inexpensive synthesis, easy modification, low immunogenicity and rapid tissue penetration.20,26 AS1411, a 26 nt G-rich DNA aptamer, which recognizes nucleolin on the surface of cancer cells with high affinity and specificity, has been widely reported for tumor targeting.27–29

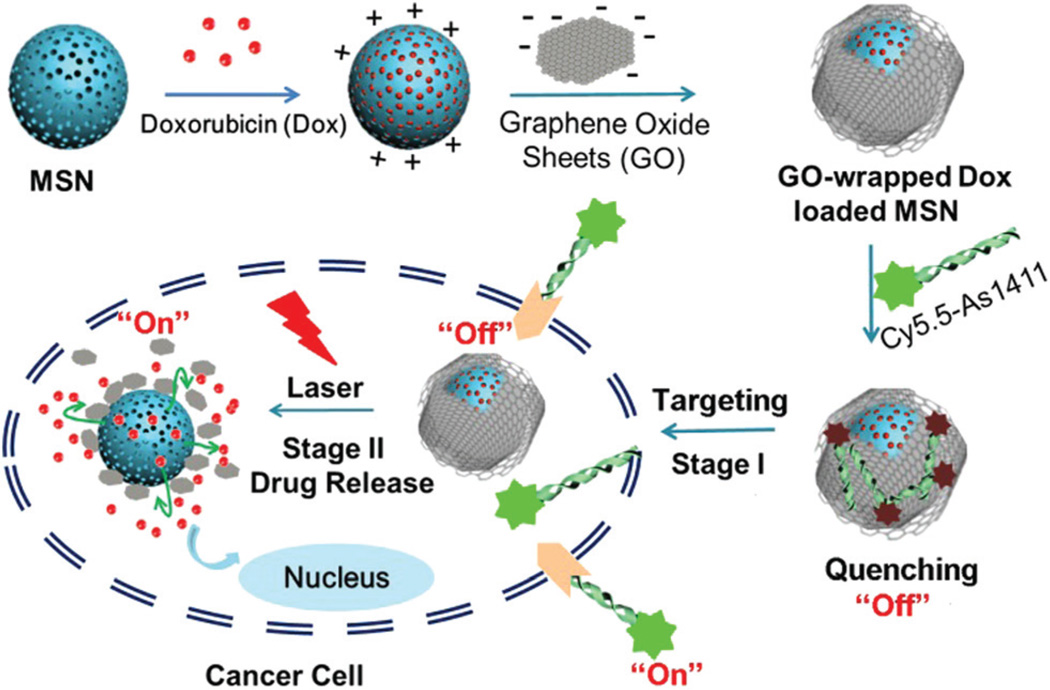

Herein we strategically designed and constructed a novel photoresponsive drug delivery system based on graphene oxide wrapped mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN@GO) for light-mediated drug release and aptamer-targeted cancer therapy (Scheme 1). The model drug, doxorubicin (Dox), was loaded on MSN. Then, negatively-charged GO nanosheets were successfully wrapped around the surface of the positively-charged MSN via electrostatic interactions. Afterwards, Cy5.5-labeled AS1411 aptamer (Cy5.5-AS1411) was assembled on the surface of GO via hydrophobic interactions and π–π stacking, with dramatic quenching of the Cy5.5 fluorescence. After selective uptake of the nanocarrier via nucleolin (NCL) receptor-mediated endocytosis, the Cy5.5 fluorescence is recovered. In the absence of laser irradiation, GO is remarkably stable and efficiently protects the loaded drug from leaking. Upon laser irradiation, GO transduces NIR light into heat and the local high temperature leads to the expansion of the GO sheets and vibration of GO and the MSNs, causing on-demand Dox release.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of GO-wrapped Dox-loaded MSN-NH2 bound with Cy5.5-labeled AS1411 aptamer and the corresponding NIR light-controlled intracellular drug release. The two “off–on” switches of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt were controlled by aptamer targeting and light triggering, respectively.

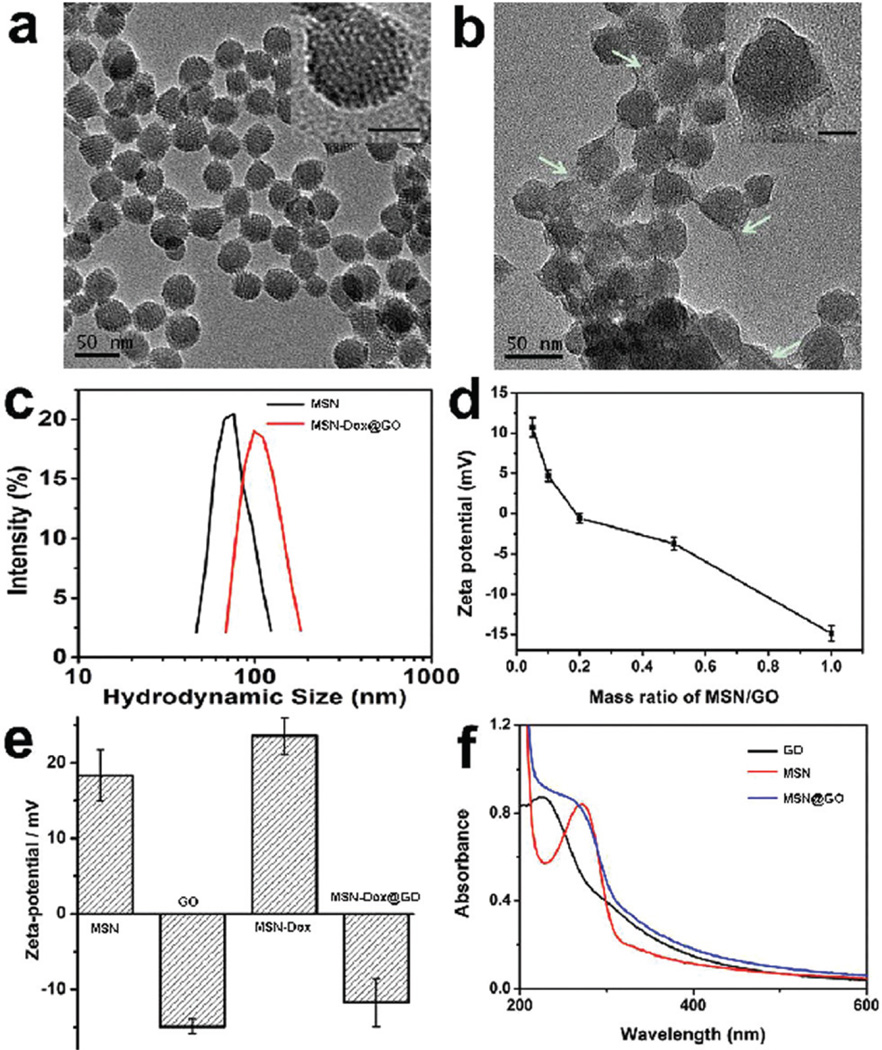

MSNs were synthesized according to a previously reported method.30,31 As shown in Fig. 1a, the MSNs present well-defined spherical nanostructures with radial mesoporous channels. Different sized GO sheets were obtained using the sonication cutting approach. The hydrodynamic size of the GO sheets decreased with prolonged sonication time (Fig. S1†). GO sheets of sizes 151 ± 11 nm after 2 h sonication were chosen for wrapping experiments. In a typical experiment, Dox was loaded on the MSNs at a pH of 7.4 (MSN-Dox) and the loading efficiency was 17% when 1 mg of MSNs was mixed with 0.5 mg of Dox. MSN-Dox was then mixed with GO under gentle sonication for a few minutes and stirred for 24 h to obtain GO wrapped MSN-Dox (MSN-Dox@GO). After GO wrapping, the TEM image shown in Fig. 1b exhibits clear evidence for the complete wrapping of GO sheets around the surface of the Dox-loaded MSNs (see high-resolution TEM image in the insets of Fig. 1a and b). The average hydrodynamic size increased from 76 to 111 nm after GO wrapping (Fig. 1c). The zeta potential for MSN-Dox@GO decreased from 12 to −15 mV upon increasing the mass ratio of GO/MSNs from 0.05 to 1 (Fig. 1d). When the mass ratio of GO/MSNs was 0.5, the zeta potentials of the MSNs, GO, MSN-Dox, and MSN-Dox@GO were 18.34, −14.9, 23.56, and −11.7 mV, respectively (Fig. 1e). The MSN-Dox@GO maintained good stability (Fig. S2 and S3†). In addition, the changes in the UV/Vis absorption spectra of the GO, MSNs and MSN@GO also demonstrated the successful wrapping of GO around the MSNs (Fig. 1f). The fluorescence of Dox was dramatically quenched after being loaded on the MSNs due to self-aggregation of the hydrophobic Dox molecules and the GO coating (Fig. S4†).

Fig. 1.

TEM images of (a) MSN-NH2, (b) GO-wrapped Dox-loaded MSN (MSN-Dox@GO) (the inset scale bar = 20 nm and the white arrows indicate GO sheets), (c) the size distribution of MSN-NH2 and MSN-Dox@GO, (d) ζ potential changes for MSN-Dox@GO with various mass ratios of GO/MSN, (e) ζ potentials for MSNs, GO sheets, MSN-Dox, and MSN-Dox@GO at a GO/MSN mass ratio of 0.5 and (f) UV/Vis absorption spectra of GO, MSN and MSN@GO in distilled H2O.

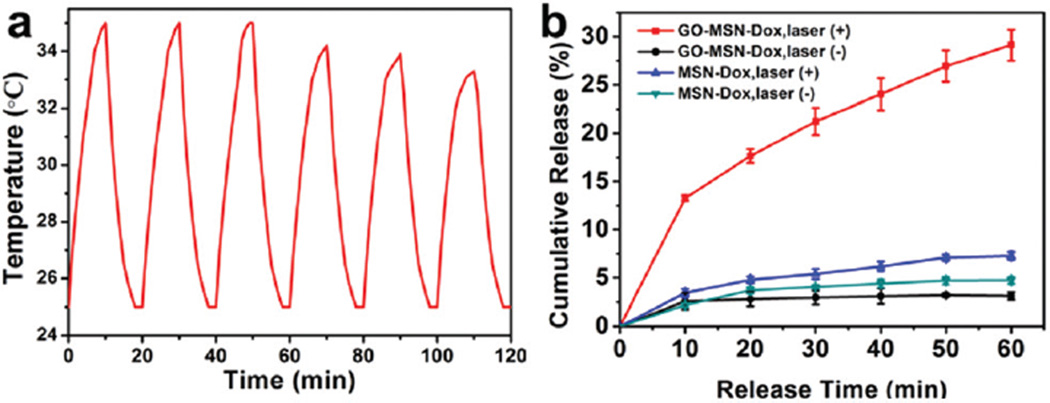

The in vitro drug release profiles of MSN-Dox@GO and MSN-Dox with and without laser irradiation were investigated in pH 7.4 buffer. The temperature change was monitored using an infrared camera. When the MSN-Dox@GO solution was irradiated by an 808 nm laser (0.25 W cm−2) for six on–off cycles, the change in temperature was consistent, exhibiting a 8–10 °C increase for each bout of laser irradiation (Fig. 2a). Fig. 2b shows the slow release of MSN-Dox without and with laser irradiation, which corroborates the slow drug release profile of typical Dox-loaded MSNs. The lack of a significant difference in the released amount of Dox with and without laser irradiation is attributed to the weak temperature increase of the MSN-Dox solution under laser irradiation (Fig. S5†). To achieve NIR light-triggered drug release, an 808 nm NIR laser at 0.25 W cm−2 was used to irradiate the MSN-Dox@GO solution, which raised the temperature by 34 °C. As the GO gatekeeper converted NIR light into heat, the resulting high local temperature as well as the expansion of the GO sheets and the vibration of GO and MSNs, consequently caused fast release of Dox. TEM images of MSN-Dox@GO after laser irradiation showed the detachment of the GO sheets from the MSNs (Fig. S6†). Since light can be operated very conveniently and precisely, MSN@GO is an ideal carrier to deliver drugs via a light-responsive mechanism with exact control of the area, time, and dosage of laser irradiation.

Fig. 2.

(a) A temperature plot of MSN-Dox@GO solution irradiated by an 808 nm laser (0.25 W cm−2) for six on–off cycles (on: 10 min, off: 10 min). (b) Dox release profiles of MSN-Dox@GO and MSN-Dox with and without NIR laser irradiation.

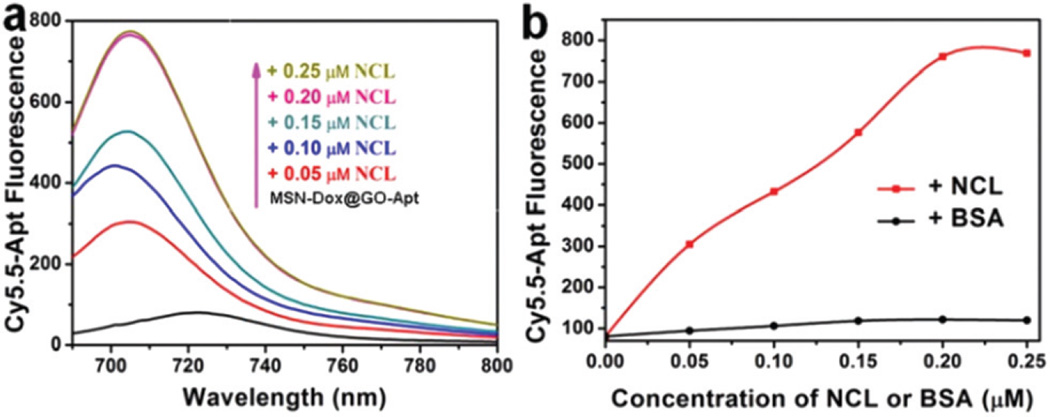

Targeted delivery is a critical demand of nanomedicine.32–34 Cy5.5-labeled AS1411 aptamer was used as a targeting ligand to functionalize the surface of GO. After incubation of Cy5.5-AS1411 and MSN-Dox@GO for 15 min, nearly 80% of the fluorescence was quenched (Fig. S7†) because of fluorescence resonance energy transfer between Cy5.5 and GO, which implies successful non-covalent assembly of Cy5.5-AS1411 on the surface of GO. The fluorescence response of Cy5.5 towards the target nucleolin (NCL) was tested against different concentrations of NCL ranging from 0.05 to 0.25 µM. No obvious change in fluorescence was observed over several aging days (Fig. S8†), which indicates that Cy5.5-AS1411 remained stable assembled on the surface of MSN-Dox@GO, and did not dissociate from the GO sheets. Fig. 3 shows that a significant increase in fluorescence was observed with increasing NCL concentration. In contrast, a negligible amount of fluorescence was recovered when incubated with bovine serum albumin (BSA), which demonstrated the high NCL binding affinity and specificity of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt.

Fig. 3.

The fluorescence response of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt towards nucleolin (NCL). (a) Fluorescence emission spectra of 0.05 µM Cy5.5-Apt quenched with GO (black line) and fluorescence recovery upon addition of NCL with concentration in the range 0.05–0.25 µM (from bottom to top). (b) The fluorescence intensity of Cy5.5-Apt with the addition of NCL and BSA.

After exposure of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt to NCL positive MCF-7 cancer cells, it selectively bound to the surfaces of the cells with high NCL expression, and then triggered receptor-mediated endocytosis. Once selective targeting was achieved Cy5.5 fluorescence was recovered. This reports the endocytosis process of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt, and suggests a suitable time to start laser irradiation. NCL specificity of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt was confirmed by effective blocking of the Cy5.5 signal when MCF-7 cells were incubated with MSN-Dox@GO-Apt and free AS1411 (Fig. S9†).

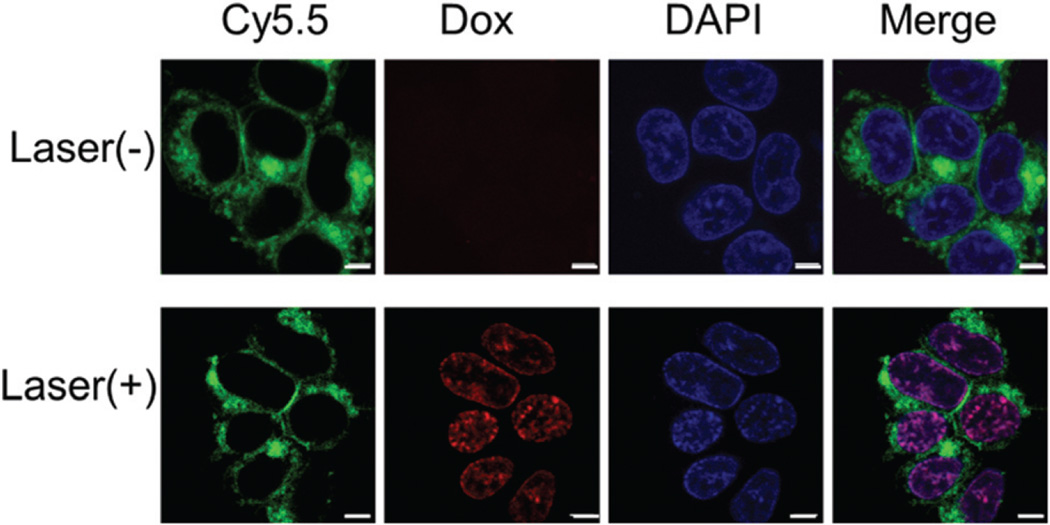

In the control experiment, with 293 T cells with low expression of NCL, no Cy5.5 fluorescence was observed regardless of incubation time (Fig. S10†). As the recovery of Cy5.5 fluorescence in MCF-7 cells was indicated, NIR light triggered Dox release was investigated. After incubation for 4 h, MCF-7 cells were irradiated with an 808 nm laser for 10 min, and then further incubated for 2 h. As shown in Fig. 4, the Cy5.5 fluorescence was observed inside the cytoplasm and Dox was released into the nucleus upon laser irradiation, while no release of Dox was observed without the presence of laser irradiation.

Fig. 4.

The fluorescence of MCF-7 cells incubated with MSN-Dox@GO-Apt (Dox equivalent concentration is 0.2 µg mL−1) for 4 h (a) without and (b) with laser irradiation (808 nm, 0.25 W cm−2) for 10 min. Dox (red color), Cy5.5-Apt (green color) and the nuclei stained with DAPI (blue color) were recorded. The scale bar is 5 µm.

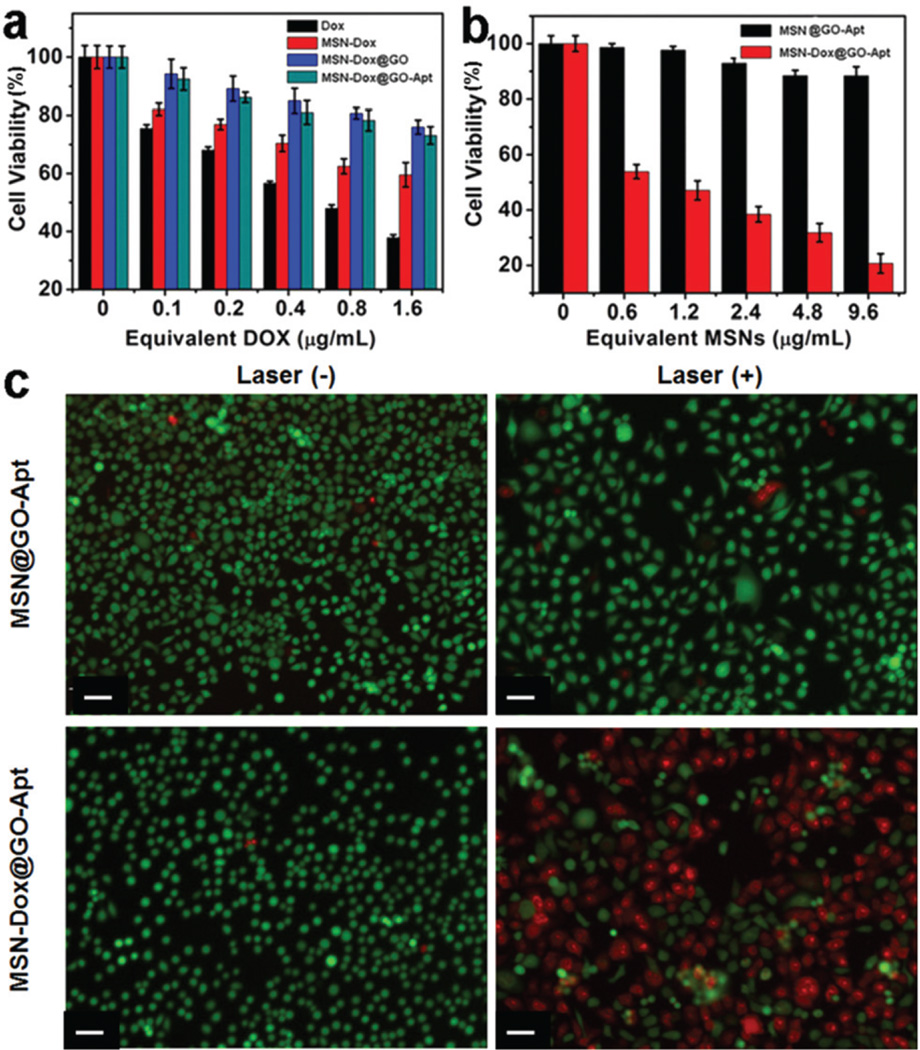

The cytotoxicity of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt, MSN-Dox@GO, MSN-Dox and free Dox to MCF-7 cells was studied by MTT assay. All four formulas exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity (Fig. 5a). MSN-Dox@GO-Apt and MSN-Dox@GO exhibited less cytotoxicity than free Dox and MSN-Dox, suggesting that only a very small amount of Dox was released from MSN-Dox@GO-Apt and MSN-Dox@GO in MCF-7 cells without laser irradiation. The chemotherapeutic efficacy of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt in MCF-7 cells was also evaluated in the presence of laser irradiation. A low power density laser of 0.25 W cm−2 was chosen to avoid killing the MCF-7 cells directly by the hyperthermic effect of GO (Fig. 5b). As the hyperthermic effect is related to GO, cells treated with MSN@GO-Apt for 4 h and then irradiated by a laser for 10 min were used as a control. No obvious decrease in viability was observed after laser irradiation, which indicates that the hyperthermic effect of MSN@GO-Apt itself does not kill cells. When MCF-7 cells were incubated with MSN-Dox@GO-Apt, a significant dose-dependent cell death was observed after laser irradiation, in accordance with the results from live/dead cell staining (Fig. 5c). We studied the cell cytotoxicity of GO on human breast cancer MCF-7 cells, which indicated that GO exhibited negligible toxicity to MCF-7 cells at all of the studied concentrations (1–10 µg mL−1) by MTT assay (Fig. S11†). Therefore we should not worry about the cytotoxicity induced by the dissociation of GO from the MSNs. The above results demonstrate that the increased cell death and loss of cell viability was caused by laser-triggered Dox release, thus inducing chemotherapy.

Fig. 5.

In vitro viability of MCF-7 cells incubated with (a) free DOX, MSN-Dox, MSN@GO-Apt and MSN-Dox@GO-Apt for 24 h, (b) MSN@GO-Apt and MSN-Dox@GO-Apt with laser irradiation for 10 min, (c) fluorescence images of MCF-7 cells treated with MSN@GO-Apt and MSN-Dox@GO-Apt at an equivalent concentration of 2.4 µg mL−1 MSNs for 4 h and then irradiated with a laser for 10 min and incubated for a further 24 h. Calcein (green, live cells) and PI (red, dead cells). The laser wavelength was 808 nm and the power density was 0.25 W cm−2. The scale bar is 10 µm.

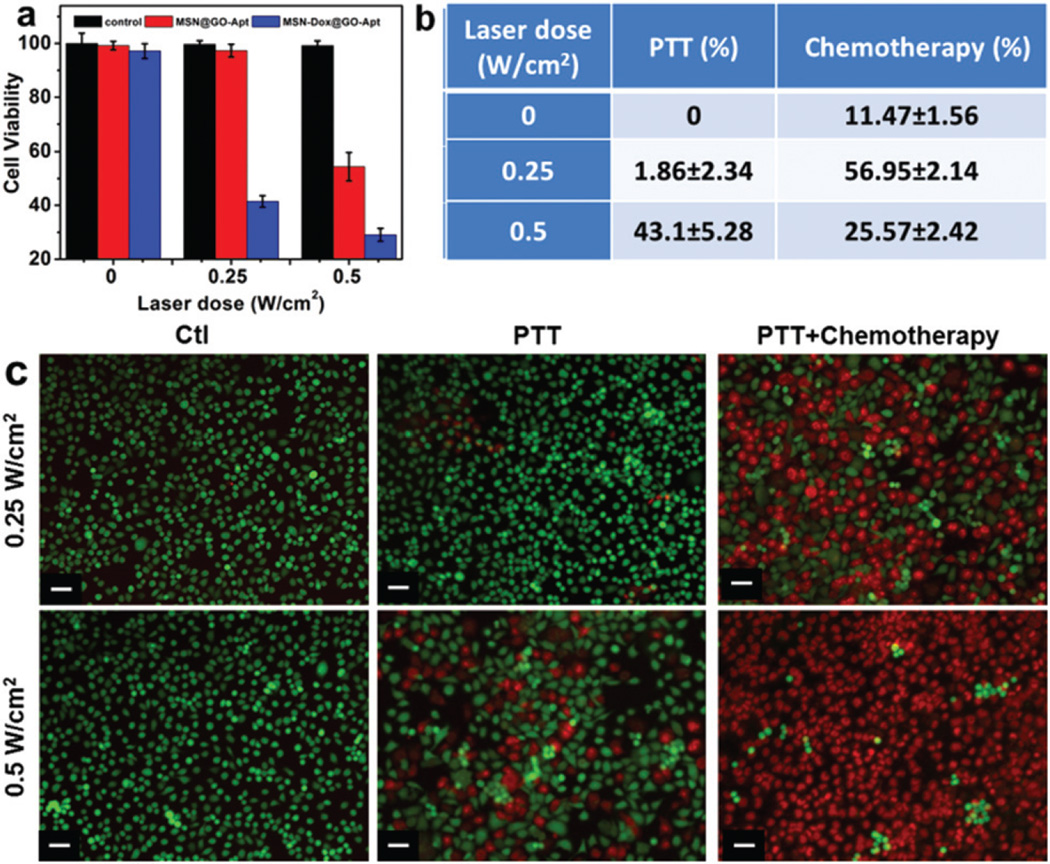

The synergistic dual-mode chemotherapy and photothermal therapy (PTT) of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt were further investigated on MCF-7 cells (Fig. 6). At low power density (0.25 W cm−2) laser irradiation, 57.0% of cells were killed by chemotherapy, and only 1.86% of cells were killed by PTT. At higher power density (0.5 W cm−2) laser irradiation 25.6% of cells were killed by chemotherapy, and 43.1% of cells were killed by PTT (Fig. 6a and b). With the increase in laser power, the main therapeutic effect shifted from chemotherapy to PTT. Similar results were also evidenced by live/dead cell staining (Fig. 6c). These results indicate that synergistic therapies of chemotherapy and PTT exhibit much higher therapeutic efficacy compared to either individual chemotherapy or PTT alone.

Fig. 6.

(a) NIR light triggered synergistic therapies of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt at different laser power densities. (b) PTT and therapy percentages of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt at different laser power densities. (c) Fluorescent imaging of MCF-7 cells treated with MSN@GO-Apt or MSN-Dox@GO-Apt at an equivalent concentration of 2.4 µg mL−1 MSNs for 4 h and then irradiated with a laser for 10 min and stained for Live/Dead assay after further incubation for 24 h (cells only irradiated with a laser were the control). Calcein (green, live cells) and PI (red, dead cells). The wavelength of the laser was 808 nm and the power density was 0.25 and 0.5 W cm−2. The scale bar is 10 µm.

Experimental section

Materials

Millipore water (18 MΩ cm; Millipore Co., USA) was used in all experiments. Nucleolin peptide was purchased from Abcam (ab25315). AS1411 aptamer with Cy5.5 modification at the 5′- end (sequence: 5′-Cy5.5-TTG GTG GTG GTG GTT GTG GTG GTG GTG G-3′) was purchased from IDT DNA, Inc. after HPLC-purification. A live/dead stain kit was purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTES, >99%), tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS), anhydrous ethanol and ammonia (NH3·H2O) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. and used as received without further purification.

Instruments

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were recorded using a Tecnai TF30 TEM (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) equipped with a Gatan Ultrascan 1000 CCD camera (Gatan, Pleasaton, CA) at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV. UV-Vis spectra were acquired using a Genesys 10S spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) with a 1 cm path length quartz cell. Fluorescence measurements were recorded on an F-7000 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Zeta potential and particle size measurements were performed using a SZ-100 nano particle analyzer (HORIBA Scientific, USA). Cell fluorescence images were observed using an IX81 Epifluorescence microscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany).

Synthesis of MSN-NH2

APTES modified MSNs were fabricated according to the reported method.35–37 Briefly, 0.29 g of CTAB was dissolved in 150 mL of 0.256 M NH3·H2O solution at 50 °C. After one hour, 2.5 mL of 0.88 M TEOS ethanol solution was added under vigorous stirring. After 15 min, 0.5 mL of APTES was added into the solution. The system was aged for another 20 h. Then the as-synthesized MSNs were centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 30 min and washed five times with water and ethanol alternatively. The nanoparticles were then transferred to 50 mL of acidic ethanol solution (1 mL of HCl–1 L of ethanol) and heated to 60 °C for two hours under stirring. The extracted nanoparticles were further washed three times with ethanol and re-dispersed in water for further use.

Synthesis of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt

Typically, 5 mg of MSNs was mixed with 10 mL of 0.25 mg mL−1 Dox phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution at pH 7.4. The mixture was stirred for 24 h in the dark. Then, Dox loaded MSNs (MSN-Dox) were collected by centrifugation at 14 000 rpm for 10 min and washed several times to remove unloaded Dox. For GO wrapping, MSN-Dox was mixed with GO under sonication for several minutes and then stirred for 24 h to obtain GO wrapped MSN-Dox (MSN-Dox@GO).

Dox loading efficiency

To evaluate the Dox-loading efficiency, the supernatant and washed solutions were assessed using a UV-Vis spectrometer at a wavelength of 490 nm to calculate the free Dox content.

In vitro release experiments

For in vitro release experiments, MSN-Dox@GO (MSN equivalent is 1 mg) was suspended in 1 mL PBS and irradiated with an 808 nm laser for 10 min and then centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 10 min to obtain the supernatant and 1 mL fresh PBS was added to the sediment. The laser spot was adjusted to cover the whole surface of the samples. This procedure was repeated 6 times. During laser irradiation, real-time thermal imaging was recorded using a SC300 infrared thermal camera (FLIR, Arlington, VA) and the temperature of the whole solution was quantified using FLIR Examiner software. Other control groups were operated under the same conditions except irradiation. The released Dox was quantified using a UV-Vis spectro-photometer.

In vitro fluorescence recovery of Cy5.5 on the MSN-Dox@GO-Apt complex

To investigate the fluorescence recovery of Cy5.5, we added nucleolin peptide, the target of the AS1411 aptamer, into the MSN-Dox@GO-Apt complex. BSA was used as a control. Fluorescence spectra were recorded using an F-7000 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Cytotoxicity assays

MTT assays were used to measure cellular viability. Human breast cancer MCF-7 cells were seeded at a density of 5000 cells per well in 96-well plates for 24 h, and then incubated with free Dox, MSN-Dox, MSN-Dox@GO or MSN-Dox@GO-Apt (the equivalent Dox concentrations are 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 µg mL−1, respectively) for another 24 h. The standard MTT assay was carried out to evaluate the cell viability. Five replicates were done for each group.

In vitro aptamer-targeting fluorescence imaging

For aptamer-targeting imaging, 105 of MCF-7 cells per well were seeded in 24-well assay plates. MSN-Dox@GO-Apt (the equivalent aptamer concentration is 0.2 µM) was added and incubated for 1, 2, and 4 h. The cells were then washed three times with PBS. 500 µL of fixing solution (1% glutaraldehyde and 10% formaldehyde) was added to each well and incubated for 30 min. Finally, the fluorescence images were recorded using an Olympus BX-51 optical system microscopy. Pictures were taken with an Olympus digital camera. 293 T cells were studied following the same procedure as a control.

NIR light triggered Dox release and therapy efficacy

To investigate therapeutic effects of NIR light triggered drug release on MCF-7 cells, 5000 cells per well were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h. Then the cells were exposed to MSN-Dox@GO-Apt or MSN@GO-Apt at different equivalent concentrations of MSNs for 4 h. The cells were then irradiated using an 808 nm laser with a power density of 0.25 W cm−2 for 10 min and incubated for a further 24 h. The standard MTT assay was carried out to evaluate the cell viability. 2 × 104 of MCF-7 cells per well were seeded in a 12-well plate for 24 h and incubated with MSN-Dox@GO-Apt or MSN@GO-Apt at an equivalent concentration of 2.4 µg mL−1 MSNs for 4 h. Then, the cells were irradiated using an 808 nm laser with a power density of 0.25 W cm−2 for 10 min, the medium was changed to a fresh one and the cells were incubated for a further 24 h, and stained using a live/dead stain kit.

NIR light triggered synergistic therapies of chemotherapy and photothermal therapy

MCF-7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5000 cells per well for 24 h. Then, cells were incubated with MSN@GO-Apt or MSN-Dox@GO-Apt solution at an equivalent concentration of 2.4 µg mL−1 MSNs for 4 h. Afterwards, the cells were irradiated with an 808 nm laser at 0.25 and 0.5 W cm−2 for 10 min, respectively. After laser irradiation, the cells were incubated at 37 °C for a further 24 h. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay and live/dead assay. The only laser irradiation group was used as control.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a novel aptamer-targeted photoresponsive drug delivery system with two “off–on” switches, based on non-covalent assembly of Cy5.5-AS1411 on the surface of graphene oxide wrapped Dox-loaded meso-porous silica nanoparticles (MSN-Dox@GO-Apt), for light-mediated drug release and aptamer-targeted cancer therapy. The first “off–on” switch was achieved by Cy5.5-AS1411 ligand directed specific targeting of breast cancer MCF-7 cells, thus leading to Cy5.5 fluorescence recovery as a real-time indicator of the endocytosis process of MSN-Dox@GO-Apt. The second “off–on” switch was conducted by laser irradiation. GO transduces NIR light into heat and the local high temperature leads to the expansion of GO sheets and vibration of GO and the MSNs, causing on-demand Dox release. This novel “off–on” PDDS system is very promising for targeted drug delivery, controllable drug release and synergistic dual-mode therapies of chemotherapy and PTT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part, by the National Key Basic Research Program of the PRC (2014CB744504, 2014CB744503, 2013CB733802 and 2011CB707700), the Major International (Regional) Joint Research Program of China (81120108013), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81201175, 81371611, 81371596, 81401465), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2014T71012 and 2013M542576) and Jiangsu planned Projects for Postdoctoral Research Funds (1301023) and by the Intramural Research Program (IRP) of the NIBIB, NIH.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c4nr07493a

References

- 1.Swaminathan S, Garcia-Amoros J, Fraix A, Kandoth N, Sortino S, Raymo FM. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:4167–4178. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60324e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mura S, Nicolas J, Couvreur P. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:991–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleige E, Quadir MA, Haag R. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2012;64:866–884. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He D, He X, Wang K, Zou Z, Yang X, Li X. Langmuir. 2014;30:7182–7189. doi: 10.1021/la501075c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rai P, Mallidi S, Zheng X, Rahmanzadeh R, Mir Y, Elrington S, Khurshid A, Hasan T. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2010;62:1094–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang P, Rong P, Lin J, Li W, Yan X, Zhang MG, Nie L, Niu G, Lu J, Wang W, Chen X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:8307–8313. doi: 10.1021/ja503115n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang P, Lin J, Wang X, Wang Z, Zhang C, He M, Wang K, Chen F, Li Z, Shen G, Cui D, Chen X. Adv. Mater. 2012;24:5104–5110. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang P, Lin J, Li W, Rong P, Wang Z, Wang S, Wang X, Sun X, Aronova M, Niu G, Leapman RD, Nie Z, Chen X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:13958–13964. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timko BP, Kohane DS. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery. 2014;11:1681–1685. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2014.930435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coll C, Bernardos A, Martinez-Manez R, Sancenon F. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:339–349. doi: 10.1021/ar3001469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Z, Wang L, Wang J, Jiang X, Li X, Hu Z, Ji Y, Wu X, Chen C. Adv. Mater. 2012;24:1418–1423. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu J, Choi E, Tamanoi F, Zink JI. Small. 2008;4:421–426. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan Q, Zhang Y, Chen T, Lu D, Zhao Z, Zhang X, Li Z, Yan CH, Tan W. ACS Nano. 2012;6:6337–6344. doi: 10.1021/nn3018365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan H, Teh C, Sreejith S, Zhu L, Kwok A, Fang W, Ma X, Nguyen KT, Korzh V, Zhao Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:8373–8377. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong R, Hemmati HD, Langer R, Kohane DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8848–8855. doi: 10.1021/ja211888a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He D, He X, Wang K, Cao J, Zhao Y. Langmuir. 2012;28:4003–4008. doi: 10.1021/la2047504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang P, Xu C, Lin J, Wang C, Wang X, Zhang C, Zhou X, Guo S, Cui D. Theranostics. 2011;1:240–250. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang K, Feng L, Shi X, Liu Z. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:530–547. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35342c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Z, Huang P, Tong G, Lin J, Jin A, Rong P, Zhu L, Nie L, Niu G, Cao F. Nanoscale. 2013;5:6857–6866. doi: 10.1039/c3nr01573d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong RM, Zhang XB, Chen Z, Tan W. Small. 2011;7:2428–2436. doi: 10.1002/smll.201100250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi M, Yang S, Peng Z, Liu C, Li J, Zhong W, Yang R, Tan W. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:3548–3554. doi: 10.1021/ac5000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Li Z, Hu D, Lin C-T, Li J, Lin Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9274–9276. doi: 10.1021/ja103169v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sreejith S, Ma X, Zhao Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:17346–17349. doi: 10.1021/ja305352d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim D-K, Barhoumi A, Wylie RG, Reznor G, Langer RS, Kohane DS. Nano Lett. 2013;13:4075–4079. doi: 10.1021/nl4014315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu C, Yang D, Mei L, Lu B, Chen L, Li Q, Zhu H, Wang T. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5:2715–2724. doi: 10.1021/am400212j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan W, Donovan MJ, Jiang J. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:2842–2862. doi: 10.1021/cr300468w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soundararajan S, Chen W, Spicer EK, Courtenay-Luck N, Fernandes DJ. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2358–2365. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo J, Gao X, Su L, Xia H, Gu G, Pang Z, Jiang X, Yao L, Chen J, Chen H. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8010–8020. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ai J, Xu Y, Lou B, Li D, Wang E. Talanta. 2014;118:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovell JF, Jin CS, Huynh E, Jin H, Kim C, Rubinstein JL, Chan WC, Cao W, Wang LV, Zheng G. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:324–332. doi: 10.1038/nmat2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang Y, Liu Y, Teng Z, Tian Y, Sun J, Wang S, Wang C, Wang J, Lu G. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2014;2:4356–4362. doi: 10.1039/c4tb00497c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z, Huang P, Zhang X, Lin J, Yang S, Liu B, Gao F, Xi P, Ren Q, Cui D. Mol. Pharm. 2009;7:94–104. doi: 10.1021/mp9001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang P, Bao L, Zhang C, Lin J, Luo T, Yang D, He M, Li Z, Gao G, Gao B, Shen F, Cui D. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9796–9809. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang P, Wang S, Wang X, Shen G, Lin J, Wang Z, Guo S, Cui D, Yang M, Chen X. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2015;11:117–125. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2015.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin YS, Abadeer N, Hurley KR, Haynes CL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:20444–20457. doi: 10.1021/ja208567v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin YS, Abadeer N, Haynes CL. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:532–534. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02923h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin YS, Haynes CL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4834–4842. doi: 10.1021/ja910846q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.