Abstract

The mammalian mitochondrial genome contains a single tRNAMet gene that gives rise to the initiator and elongator tRNAMet. It is generally believed that mitochondrial protein synthesis begins with formylmethionyl-tRNA, which indicates that the formylation of mitochondrial Met-tRNA specifies its participation in initiation through its interaction with initiation factor 2 (IF-2). However, recent studies in yeast mitochondria, suggest that formylation is not required for protein synthesis. In addition, bovine IF-2mt could replace yeast IF-2mt in strains that lack fMet-tRNA which suggests that this paradigm may extend to mammalian mitochondria. Here, the importance of the formylation of mitochondrial Met-tRNA for the interaction with IF-2mt was investigated by measuring the ability of bovine IF-2mt to bind mitochondrial fMet-tRNA. In direct binding experiments, bovine IF-2mt has a 25-fold greater affinity for mitochondrial fMet-tRNA than Met-tRNA, using either the native mitochondrial tRNAMet or an in vitro transcript of bovine mitochondrial tRNAMet. In addition, IF-2mt will not effectively stimulate mitochondrial Met-tRNA binding to mitochondrial ribosomes, exhibiting a 50-fold preference for fMet-tRNA over Met-tRNA in this assay. Finally, the region of IF-2mt responsible for the interaction with fMet-tRNA was mapped to the C2 sub-domain of domain VI of this factor.

INTRODUCTION

Of the 22 tRNAs encoded in mammalian mitochondrial DNA, there is a single tRNA that represents each amino acid, except for tRNASer and tRNALeu, which have 2 isoacceptors each. In mammals, there is no evidence of tRNA import into mitochondria, hence these species represent the complete set of tRNAs available for the translational apparatus. The presence of a single species of tRNAMet is quite unusual. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic cytoplasmic translational systems use two tRNAMet species, one designated for initiation and one for elongation. Even the mitochondria of most lower eukaryotes possess two specialized tRNAMet species. The mammalian mitochondrial translational system, therefore, must have a unique mechanism by which this single tRNAMet species is partitioned between the initiation and elongation phases of protein synthesis. In addition to the single tRNAMet species, mitochondria possess an alternate genetic code in which both AUG and AUA code for methionine (1). A novel modification (5-formyl cytidine) in the first position of the anticodon in tRNAMet may give rise to its ability to decode both AUG and AUA (2,3).

Translational initiation in prokaryotes and mammalian mitochondria generally occurs with fMet-tRNA (4). The gene that encodes the bovine mitochondrial methionyl-tRNA transformylase (MTFmt) has been cloned and the protein has been studied biochemically (5–7). The partitioning of tRNAMet into either the initiation phase or the elongation phase of protein synthesis is assumed to occur by a competition between MTFmt and mitochondrial elongation factor Tu (EF-Tumt) for the Met-tRNAMet (6). Once Met-tRNAMet is formylated by MTFmt, it becomes a substrate for mitochondrial initiation factor 2 (IF-2mt) and participates in the initiation phase of protein synthesis. However, if Met-tRNA binds to EF-Tumt:GTP before it is formylated, it acts as an elongator tRNA. This partitioning mechanism requires that IF-2mt strongly discriminates against Met-tRNAMet and that EF-Tumt preferentially binds Met-tRNAMet. For bovine IF-2mt, a strong preference for fMet-tRNA has been demonstrated using both the yeast and Escherichia coli initiator tRNAMet species (8). It has also been shown that EF-Tumt strongly discriminates against E.coli fMet-tRNAfMet (9). Taken together, these observations suggest that the formylation of mitochondrial tRNAMet governs its identity as either an initiator or an elongator tRNAMet.

Recently, however, studies in yeast mitochondria have suggested that formylation of Met-tRNA is not required for mitochondrial protein synthesis. Yeast mutants that lacked the ability to formylate the mitochondrial initiator Met-tRNA had normal protein synthesis, which indicates that formylation is not essential for mitochondrial translation in yeast (10). Further, bovine IF-2mt, at least, when over-expressed in yeast, can support translation in the yeast mitochondria that lacks the ability to formylate Met-tRNAMet (11). These data prompted the suggestion that formylation of Met-tRNA may not be required for translation in mammalian mitochondria. To further understand the role of formylation of Met-tRNA in the yeast mitochondria, yeast IF-2mt was cloned and characterized biochemically (12). In contrast to previous studies on bovine IF-2mt, yeast IF-2mt showed a small but significant degree of binding to Met-tRNAMet (12). These observations support the in vivo findings that formylation of initiator tRNA is not essential in the yeast mitochondrial translational system.

Here, we have investigated the interaction of bovine IF-2mt with mitochondrial fMet-tRNA to determine the role of formylation of mitochondrial Met-tRNA in mammalian mitochondrial protein synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific or Sigma. [35S]Met was obtained from Perkin Elmer Life Science Products. SUPERase•In™ RNase inhibitor was purchased from Ambion. Pyruvate kinase and folinic acid were from Sigma. E.coli tRNA was purchased from Roche. E.coli tRNAfMet was partially purified from crude E.coli tRNA as described previously (13). The bovine mitochondrial tRNAMet (mtRNAMet) transcript and human mitochondrial methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MetRSmt) were purified as described previously (14). Crude bovine mitochondrial tRNA was kindly provided by Senyene Eyo Hunter (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). IF-2mt and various N- or C-terminal truncated derivatives were expressed and purified as described by A. Spencer and L. Spremulli (submitted for publication). Mitochondrial initiation factor 3 (IF-3mt) was kindly provided by Dr Emine Koc (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). Bovine liver mitochondria, 55S ribosomes and 28S subunits were prepared as described previously (15,16).

Expression and purification of bovine MTFmt

A plasmid containing the cDNA for bovine MTFmt was kindly provided by Dr Kimitsuna Watanabe (University of Tokyo). The DNA was transformed into E.coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells (Stratagene) for expression. A single colony of cells that harbored the pET15-bovine MTFmt construct was used to inoculate 10 ml of 2YT media (17) that contained 50 μg/ml of ampicillin. This culture was grown at 37°C to saturation and was used to inoculate 2 l of 2YT media (2 × 1 l), which were grown at 37°C to an A600 of 0.6–0.8. The expression of bovine MTFmt was induced by the addition of 140 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Expression was carried out at 18°C for 16 h on a rotary shaker at 150 r.p.m. Following expression, cells were harvested, resuspended in a volume of at least 100 ml of buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6) and pelleted by low speed centrifugation (4000 g for 30 min at 4°C). At this point, cells were either fast-frozen and stored at −70°C until future use or treated as described below.

Cell pellets (∼9 g) were resuspended in Buffer 1 [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 500 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM imidazole, 3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (BME) and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride] at a ratio of ∼10 ml/g cell weight and sonicated at 60 W on ice using 1 s bursts with 4 s cooling periods for 12 min (performed in 3 min intervals). DNase I (5 μg/ml) was added and the lysate was subjected to centrifugation at 38 000 r.p.m. in a Beckman Type 60 rotor for 1 h at 4°C. Following centrifugation, 1.0 ml of Ni-NTA resin (50% slurry in Buffer 1) was added to the supernatant and incubation was carried out at 4°C for 1 h with rocking. The sample was transferred to a polypropylene column and the resin was subsequently washed with ∼100 ml Buffer 1. Bovine MTFmt was eluted from the Ni-NTA resin with Buffer 1 containing 220 mM imidazole for 20 min at 4°C. The elution was repeated twice and all eluates were combined before dialyzing the sample against 250 ml of Buffer 2 [20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 3 mM BME, 100 mM KCl and 10% glycerol] for 45 min at 4°C with one change of buffer and an additional 45 min of dialysis. This preparation gave a major band on SDS–PAGE with an apparent molecular weight of ∼40 kDa and was estimated to be at least 50% pure by Coomassie staining. The sample was used without further purification since it was active and free of nuclease contamination (data not shown).

Preparation of Met-tRNAMet

The large-scale aminoacylation of partially purified E.coli tRNAfMet was carried out essentially as described (18).The large-scale aminoacylation of a bovine mitochondrial tRNAMet transcript was carried out in a reaction (1 ml) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM ATP, 0.2 mM spermine, 0.2 mg/ml BSA, 8 μM [35S]Met (15 000 c.p.m./pmol), 260 μg of partially purified human MetRSmt, 100 U SUPERase•In™ and 300 pmol of the bovine mtRNAMet transcript. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and the tRNA was purified by two extractions with phenol and one extraction with chloroform. The tRNA was precipitated with ethanol overnight at −20°C and resuspended in 10 mM potassium succinate (pH 6.0). The large-scale aminoacylation of native bovine mtRNAMet was carried out as described above except that the reaction mixtures contained 120 μg of human MetRSmt and 190 μg of crude native bovine mitochondrial tRNA.

Formylation activity of bovine MTFmt

Folinic acid (6.4 mg) was dissolved in 1 ml of 100 mM HCl containing 5 mM DTT and incubated in the dark, at room temperature, for 12 h. The sample was diluted to 10 ml with distilled H2O to a final concentration of 1.25 mM. The ability of bovine MTFmt to formylate Met-tRNA was monitored using thin layer chromatography (TLC). Formylation reactions (10 μl) contained 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 0.1 mM EDTA, 150 mM KCl, 7 mM MgCl2, 10 mM BME, 10 pmol (1 μM) E.coli [35S]Met-tRNAfMet (5000 c.p.m./pmol), 1 μg of partially purified bovine MTFmt and, where indicated, 0.125 mM folinic acid. Following incubation at 37°C for 10 min, 0.5 M NaOH was added to a final concentration of 0.1 M and incubation was continued at 37°C for 30 min. Approximately one-tenth of the reaction mixture was spotted on a Whatman LK2 TLC plate that had previously been run with distilled H2O and dried. The mobile phase for TLC analysis was butanol/acetic acid/H2O (4:1:1). The plate was dried and placed on a phosphor screen for at least 12 h. The [35S]fMet was visualized by phosphorimaging with a Molecular Dynamics' Storm 840.

To measure the ability of MTFmt to formylate either a bovine mitochondrial Met-tRNAMet transcript or native bovine mitochondrial Met-tRNAMet, the formylation reaction was carried out as described above except that it contained 6 pmol (0.6 μM) [35S]Met-tRNAMet (5000 c.p.m./pmol) transcript or 1.5 pmol (0.15 μM) of native mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNAMet (15 000 c.p.m./pmol).

Preparation of mitochondrial fMet-tRNAMet

Large-scale charging and formylation of mitochondrial tRNAMet was performed in a coupled assay essentially as described above for the aminoacylation of mtRNAMet with the following modifications. Reaction mixtures (1 ml) contained 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM ATP, 0.2 mM spermine, 0.2 mg/ml BSA, 8 μM [35S]Met (15 000 c.p.m./pmol), 100 U SUPERase•In™, 0.125 mM folinic acid, 340 μg of partially purified human MetRSmt, 50 μg of partially purified bovine MTFmt and 300 pmol of the bovine mtRNAMet transcript. For large-scale aminoacylation and formylation of the native bovine mtRNAMet, reaction mixtures (1 ml) were prepared as described above except that they contained 120 μg of partially purified human MetRSmt and 210 μg of crude native mitochondrial tRNA. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and the tRNA was purified from the reaction components as described above. Following purification of the tRNA, an aliquot of the products was analyzed for formylation by using the TLC procedure.

Interaction of bovine IF-2mt with mitochondrial fMet-tRNAMet

The RNase protection assays were carried out essentially as described (19). Reaction mixtures (25 μl) contained 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 2 mM DTT, 7 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NH4Cl, 0.25 mM guanosine 5′-[β,γ-imido]triphosphate (GDPNP), 2 pmol (0.08 μM) bovine mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNAMet transcript or native bovine mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNAMet (15 000 c.p.m./pmol) and the indicated amounts of the mature form of IF-2mt (typically 2.8–10 μM). Following incubation at 0°C for 15 min, 5 μg of RNase A was added. Incubation was continued for an additional 30 s at 0°C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 3 ml of ice-cold 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Incubation at 0°C was continued for 10 min. The precipitate formed was collected on nitrocellulose filters which were washed with 2 ×3 ml cold 5% TCA and dried for 6 min at 100°C. The amount of [35S]fMet-tRNA remaining was determined by scintillation counting. A blank representing the amount of [35S]fMet-tRNA that remained in the absence of IF-2mt was subtracted from each point (generally <0.1 pmol).

The ability of various derivatives of IF-2mt to bind mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA was measured as described above using 3 pmol (0.12 μM) bovine mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA transcript and 0.6–1.2 μM of each derivative. For direct comparison of each derivative, the ability of 1.0 μM of each IF-2mt derivative to protect 2.5 pmol (0.1 μM) of the bovine mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA transcript was measured. The remainder of the assay was carried out as described above.

Initiation complex formation on mitochondrial ribosomes with mitochondrial fMet-tRNAMet

The ability of IF-2mt to stimulate the binding of mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA to 28S subunits was measured in an in vitro binding assay essentially as described previously (8,20). Reaction mixtures (50 μl) contained 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM spermine, 35 mM KCl, 7.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM GDPNP, 5 μg poly(A,U,G), 10 U SUPERase•In™, 2.5 pmol (0.05 μM) 28S subunits, 0.13–3 pmol (2.6–60 nM) of mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA (15 000 c.p.m./pmol) and the indicated amounts of IF-2mt (3–7 pmol, 0.06–0.14 μM). Following incubation of the reactions at 27°C for 20 min, 3 ml of ice-cold buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 35 mM KCl and 7.5 mM MgCl2] was added and the reactions were filtered through a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore type HA). Each filter was washed twice with 3 ml of the above buffer and dried at 100°C for 6 min. The amount of [35S]fMet-tRNA bound to the ribosome was determined by liquid scintillation counting. A blank representing the amount of [35S]fMet-tRNA that bound to the 28S subunit in the absence of IF-2mt at each concentration of fMet-tRNA was subtracted from each value (∼0.01–0.03 pmol).

The ability of IF-2mt to promote the binding of mitochondrial fMet-tRNA to mitochondrial 55S ribosomes was carried out essentially as described above, except that reaction mixtures (50 μl) contained 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM spermine, 35 mM KCl, 7.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM GTP, 1.25 mM phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), 0.5 U pyruvate kinase, 5 μg poly(A,U,G), 10 U SUPERase•In™, 20 pmol (0.4 μM) mitochondrial IF-3, 3.0–3.5 pmol (0.06–0.07 μM) 55S ribosomes, 0.125–1.5 pmol (2.5–30 nM) of either native or the transcript of bovine mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA (15 000 c.p.m./pmol) and the indicated amounts of IF-2mt (4–14 pmol, 0.08–0.28 μM). The reactions were incubated at 27°C for 20 min and treated as described above. A blank representing the amount of [35S]fMet-tRNA binding to the 55S ribosome in the absence of IF-2mt (∼0.01–0.04 pmol) at each concentration of fMet-tRNA has been subtracted from each value.

RESULTS

Ability of bovine MTFmt to formylate mitochondrial tRNAMet

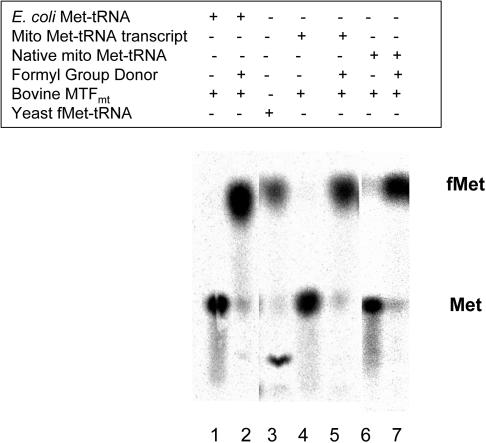

The ability of bovine MTFmt to formylate various Met-tRNAMet substrates was tested to assess whether the enzyme was active with the transcript of the tRNAMet gene as well as with the native tRNA. Following the reaction, the ester bond on the tRNA was hydrolyzed by NaOH, releasing the radiolabeled amino acid that was analyzed for formylation by TLC, which clearly separates Met and fMet. The primary determinant for substrate recognition by bovine MTFmt is the amino acid methionine, and previous studies have shown that E.coli Met-tRNAfMet is efficiently formylated by the mitochondrial enzyme (6,7). E.coli Met-tRNA was initially used to test the experimental approach for monitoring the formylation reaction, before using the mitochondrial Met-tRNA. As expected, bovine MTFmt efficiently formylated the heterologous E.coli Met-tRNAfMet substrate in the presence of the formyl group donor (Figure 1, lanes 1 and 2) (7). Yeast [35S]fMet-tRNA was used as a control for the location of fMet in these experiments and contains a small amount of methionine oxidation products that have a lower Rf value than methionine (Figure 1, lane 3). In the presence of the formyl group donor, bovine MTFmt effectively formylated the in vitro transcript of mitochondrial Met-tRNAMet (Figure 1, lanes 4 and 5) and the native mitochondrial Met-tRNAMet (Figure 1, lanes 6 and 7). Under the conditions used, close to 100% of the mitochondrial Met-tRNA could be formylated.

Figure 1.

TLC analysis of the formylation of Met-tRNA by bovine MTFmt. Formylation reactions contained bovine MTFmt and either E.coli [35S]Met-tRNA or mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA as indicated. The numbers in parentheses indicate the amount applied in each lane in the TLC analysis. Lane 1: E.coli [35S]Met-tRNA (1 pmol) in the absence of a formyl group donor. Lane 2: E.coli [35S]Met-tRNA (1 pmol) in the presence of a formyl group donor. Lane 3: yeast [35S]fMet-tRNA (1 pmol) prepared as described in (18) as a marker for fMet. Lane 4: mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA transcript (1 pmol) in the absence of a formyl group donor. Lane 5: mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA transcript (1 pmol) in the presence of a formyl group donor. Lane 6: native mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA (0.2 pmol) in the absence of a formyl group donor. Lane 7: native mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA (0.2 pmol) in the presence of a formyl group donor.

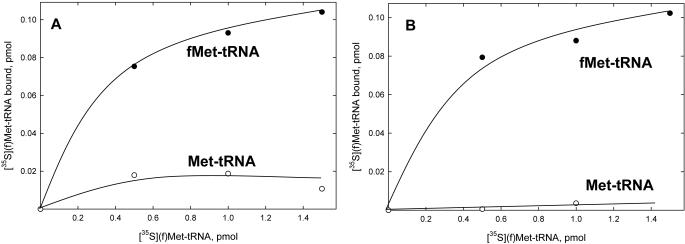

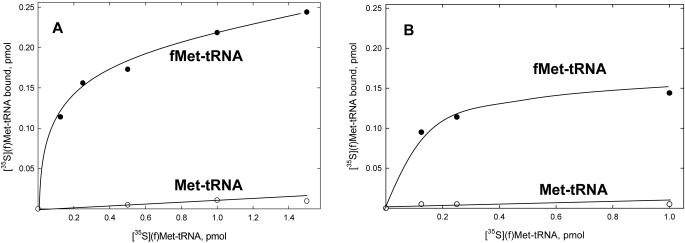

Interaction of IF-2mt with mitochondrial fMet-tRNAMet

The ability of bovine IF-2mt to bind formylated and unformylated Met-tRNA in solution was assessed by measuring the amount of fMet-tRNA protected from hydrolysis by RNase A in the presence of increasing amounts of IF-2mt. The binding of fMet-tRNA and Met-tRNA to bovine IF-2mt was determined both for the in vitro transcript and for the native bovine mitochondrial fMet-tRNAMet. Bovine IF-2mt clearly has a much higher affinity for fMet-tRNAMet and discriminates against Met-tRNA when either the transcript or the native mitochondrial tRNAMet is used (Figure 2). The amount of protection achieved with the transcript is slightly higher than that obtained with the native fMet-tRNAMet, which indicates that the modified nucleotides present in the native bovine mtRNAMet do not play a role in the recognition of mitochondrial fMet-tRNAMet by bovine IF-2mt. These modifications include two pseudouridines and the f5C that is located in the first position of the anticodon. The lower degree of binding to the native mitochondrial fMet-tRNAMet could also indicate that the presence of a large excess of non-specific mitochondrial tRNA interferes with the binding to IF-2mt. Nonetheless, the binding of mitochondrial fMet-tRNA to bovine IF-2mt was at least 50-fold greater than the binding observed with mitochondrial Met-tRNA.

Figure 2.

Interaction of bovine IF-2mt with mitochondrial fMet-tRNA. The ability of bovine IF-2mt to protect mitochondrial fMet-tRNA from hydrolysis by RNase A was measured as described in Materials and Methods. A blank representing the amount of [35S]fMet-tRNA that remained in the absence of IF-2mt was subtracted from each point. Data were fit by linear least-squares analysis. (A) Protection assays contained 2 pmol of either mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA transcript (closed circles) or 2 pmol of mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA transcript (open circles) and the indicated amounts of IF-2mt. (B) Protection assays contained 2 pmol of either native mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA (closed circles) or 2 pmol native mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA (open circles) and the indicated amounts of IF-2mt.

The strong preference of IF-2mt for fMet-tRNA contrasts with the weaker, 4-fold, preference for fMet-tRNA observed with yeast IF-2mt (12). This measurement, however, was done in a filter binding assay in the absence of magnesium and may not reflect a biologically relevant interaction (12). Similar to bovine IF-2mt, yeast IF-2mt did not protect the unformylated Met-tRNA in a RNase protection assay (12). It should also be noted that GDPNP did not affect the binding of fMet-tRNA to bovine IF-2mt. The same observation was made for the interaction of E.coli IF-2 with fMet-tRNA (21).

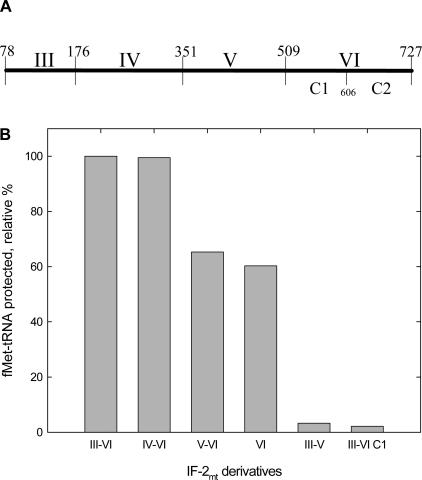

Bovine IF-2mt is organized into four domains and contains the equivalent of domains III–VI of E.coli IF-2 (Figure 3A) (22). To determine the domain(s) of bovine IF-2mt involved in the interaction with mitochondrial fMet-tRNA, the ability of a number of IF-2mt derivatives truncated at the N- and/or C-terminus to bind mitochondrial fMet-tRNA was measured in the RNase protection assay. Initially, the ability of the various derivatives to protect fMet-tRNA was determined for several concentrations of IF-2mt. The protection of [35S]fMet-tRNA was linear for each derivative over the concentration range tested (0.6–1.2 μM) (data not shown). To simplify the analysis, the ability of each derivative to bind mitochondrial fMet-tRNA was measured at a single concentration of IF-2mt (1.0 μM) (Figure 3B). There was no significant difference in the ability of either the domains III–VI or the domains IV–VI derivative to bind fMet-tRNA (Figure 3B). Thus, domain III does not appear to play a role in the binding of fMet-tRNA to IF-2mt. Removal of domain IV, however, caused a 40% reduction in the ability of IF-2mt to bind fMet-tRNA. The isolated domain VI alone was capable of binding fMet-tRNA (Figure 3B), although it was somewhat less active than the full-length factor. The decrease in binding observed in both the domains V and VI, and domain VI derivatives does not imply a direct role of domain IV in the interaction with fMet-tRNA, but presumably reflects the influence of domain IV on the overall conformation of IF-2mt (A.C. Spencer and L.L. Spremulli, unpublished data). Both derivatives lacking the C2 sub-domain of domain VI (domains III–V and domains III–VI C1) were completely inactive in binding fMet-tRNA. Thus, it appears that domain VI of IF-2mt is responsible for the interaction of IF-2mt with fMet-tRNA. These data indicate that, like prokaryotic IF-2, domain VI C2 is directly responsible for the interaction with fMet-tRNA (23–26).

Figure 3.

Binding of various IF-2mt derivatives to mitochondrial fMet-tRNA. (A) Domain organization of bovine IF-2mt and the derivatives used to determine the domain(s) of IF-2mt responsible for the interaction with fMet-tRNA. The domains have been assigned based on the E.coli IF-2 nomenclature (22) and the amino acid residues that encompasses each domain are indicated. (B) The relative percentage of fMet-tRNA protected was calculated based on the amount of [35S]fMet-tRNA (2.5 pmol input, 0.1 μM) protected by 1.0 μM of each derivative. The percentage of fMet-tRNA protected by the full-length IF-2mt was set at 100% (∼5% of input tRNA) to facilitate comparison. The amount of [35S]fMet-tRNA that remained in the absence of IF-2mt has been subtracted from each value (0.05 pmol).

Initiation complex formation on mitochondrial ribosomes with mitochondrial fMet-tRNA

The ability of bovine IF-2mt to stimulate the binding of mitochondrial fMet-tRNA to mitochondrial 28S subunits was measured in the presence of poly(A,U,G) and a non-hydrolyzable analogue of GTP, GDPNP (Figure 4). In the context of the small ribosomal subunit and the synthetic mRNA, bovine IF-2mt prefers the formylated mitochondrial Met-tRNA transcript up to 10-fold over the unformylated Met-tRNA (Figure 4A). Similarly, there is also a clear discrimination of the native mitochondrial fMet-tRNA over the native Met-tRNA by bovine IF-2mt in the context of 28S subunits (Figure 4B). Bovine IF-2mt prefers the native mitochondrial fMet-tRNA over Met-tRNA by ∼25-fold. When assayed on E.coli 30S subunits, yeast IF-2mt showed only a 6- to7-fold preference for fMet-tRNA over Met-tRNA (12).

Figure 4.

Binding of mitochondrial fMet-tRNA to mitochondrial 28S subunits in the presence of IF-2mt. (A) Reaction mixtures contained 2.5 pmol (0.05 μM) 28S subunits, 3 pmol (0.06 μM) bovine IF-2mt and the indicated amounts of mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA transcript (closed circles) or mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA transcript (open circles). Curves represent a visual best-fit of the data. (B) Reaction mixtures contained 2.5 pmol (0.05 μM) 28S subunits, 7 pmol (0.14 μM) IF-2mt and the indicated amounts of native mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA (closed circles) or native mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA (open circles).

The ability of bovine IF-2mt to stimulate fMet-tRNA binding to mitochondrial 55S ribosomes was measured in the presence of poly(A,U,G), GTP and mitochondrial IF-3 (Figure 5). Again, bovine IF-2mt clearly prefers both the transcript and the native mitochondrial fMet-tRNAMet by ∼20-fold and 50-fold, respectively (Figure 5A and B).

Figure 5.

Binding of mitochondrial fMet-tRNA to mitochondrial 55S ribosomes in the presence of bovine IF-2mt. (A) Reaction mixtures contained 3.5 pmol (0.07 μM) 55S ribosomes, 14 pmol (0.3 μM) IF-2mt and the indicated amounts of mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA transcript (closed circles) or mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA transcript (open circles). Curves represent a visual best-fit of the data. (B) Reaction mixtures contained 3 pmol (0.06 μM) 55S ribosomes, 4 pmol (0.08 μM) IF-2mt and the indicated amounts of native mitochondrial [35S]fMet-tRNA (closed circles) or native mitochondrial [35S]Met-tRNA (open circles).

DISCUSSION

In contrast to recent studies in yeast mitochondria, it is clear that bovine IF-2mt strongly prefers mitochondrial fMet-tRNA over Met-tRNA. These observations support the idea that protein synthesis in mammalian mitochondria does in fact involve fMet-tRNA. Earlier support of this idea comes from the analysis of the N-terminal amino acid of mitochondrially synthesized proteins, which were found to contain formylmethionine, as well as the requirement of N10-formyl tetrahydrofolate for mitochondrial protein synthesis (4,10). In addition, the discovery of Met-tRNA transformylase activity in bovine mitochondria gave further support to the belief that fMet-tRNA initiates mitochondrial protein synthesis, as it does in prokaryotic systems (6).

The observations made here are in contrast to those made in vivo in yeast where it has been observed that bovine IF-2mt can support protein synthesis in the absence of formylated Met-tRNA (11). One explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that bovine IF-2mt was over-expressed in these cells that perhaps compensated for its low affinity for Met-tRNA. A similar increase in the levels of IF-2 was observed in an E.coli mutant capable of initiating protein synthesis without formylated initiator tRNA (27,28). However, at physiological levels of IF-2mt, the pathway of translational initiation in mitochondria would occur via fMet-tRNA.

Biochemical data on bacterial IF-2 emphasizes the importance of the formyl group for the recognition of the initiator tRNA by IF-2. Bacterial IF-2 selects the initiator tRNA to a significant extent on the basis of the fMet moiety (29,30). Studies on Thermus thermophilus IF-2 also showed that fMet-AMP could be used as a minimal substrate for IF-2 (24). A portion of IF-2, the C2 sub-domain (Figure 3A), binds fMet-tRNA with the same affinity as full-length IF-2 (25). The structure of the C2 sub-domain of domain VI of Bacillus stearothermophilus IF-2 has been solved using NMR (31) and folds into a β-barrel similar to domain II of EF-Tu. The combination of structural information and mutagenesis data on residues near the surface of IF-2 contributed to the mapping of the binding site for fMet-tRNA on IF-2 (32). Several conserved amino acid residues in B.stearothermophilus IF-2 are important for fMet-tRNA binding (32). These include Arg-700 which lies close to the formyl group, Lys-699 and Lys-702 which are necessary for fMet-tRNA binding and Cys-668 and Gly-715 which are thought to create a groove to accommodate the Met side chain (32). The majority of these residues are conserved in IF-2mt indicating a commonality in the preferential binding to fMet-tRNA for both bacterial and mitochondrial IF-2.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Senyene Eyo Hunter for the gift of crude mitochondrial tRNA and Emine Koc for the gift of human mitochondrial IF-3.

REFERENCES

- 1.Watanabe K. and Osawa,S. (1995) tRNA sequences and variations of the genetic code. In Soll,D. and RajBhandary,U. (eds), tRNA: Structure, Biosynthesis and Function. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, pp. 225–250. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takemoto C., Ueda,T., Miura,K. and Watanabe,K. (1999) Nucleotide sequences of animal mitochondrial tRNAs(Met) possibly recognizing both AUG and AUA codons. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser., 42, 77–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takemoto C., Koike,T., Yokogawa,T., Benkowski,L., Spremulli,L.L., Ueda,T., Nishikawa,K. and Watanabe,K. (1995) The ability of bovine mitochondrial transfer RNAMet to decode AUG and AUA codons. Biochimie, 77, 104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bianchetti R., Lucchini,G., Crosti,P. and Tortora,P. (1977) Dependence of mitochondrial protein synthesis on formylation of the initiator methionyl-tRNAf. J. Biol. Chem., 252, 2519–2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeuchi N., Ueda,T. and Watanabe,K. (1998) Expression and characterization of bovine mitochondrial methionyl-tRNA transformylase. J. Biochem., 124, 1069–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi N., Kawakami,M., Omori,A., Ueda,T., Spremulli,L.L. and Watanabe,K. (1998) Mammalian mitochondrial methionyl-tRNA transformylase from bovine liver: purification, characterization and gene structure. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 15085–15090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeuchi N., Vial,L., Panvert,M., Schmitt,E., Watanabe,K., Mechulam,Y. and Blanquet,S. (2001) Recognition of tRNAs by methionyl-tRNA transformylase from mammalian mitochondria.J. Biol. Chem., 276, 20064–20068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao H.-X. and Spremulli,L.L. (1991) Initiation of protein synthesis in animal mitochondria: purification and characterization of translational initiation factor 2. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 20714–20719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woriax V., Spremulli,G. and Spremulli,L.L. (1996) Nucleotide and aminoacyl-tRNA specificity of the mammalian mitochondrial elongation factor EF-Tu:Ts complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1307, 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y., Holmes,W.B., Appling,D.R. and RajBhandary,U.L. (2000) Initiation of protein synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria without formylation of the initiator tRNA. J. Bacteriol., 182, 2886–2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tibbetts A.S., Oesterlin,L., Chan,S.Y., Kramer,G., Hardesty,B. and Appling,D.R. (2003) Mammalian mitochondrial initiation factor 2 supports yeast mitochondrial translation without formylated initiator tRNA. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 31774–31780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garofalo C., Trinko,R., Kramer,G., Appling,D.R. and Hardesty,B. (2003) Purification and characterization of yeast mitochondrial initiation factor 2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 413, 243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker R.T. and RajBhandary,U.L. (1972) Studies on polynucleotides. CI. Escherichia coli tyrosine and formylmethionine transfer ribonucleic acids: effect of chemical modification of 4-thiouridine to uridine on their biological properties. J. Biol. Chem., 247, 4879–4892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer A.C., Heck,A.H., Takeuchi,N., Watanabe,K. and Spremulli,L.L. (2004) Characterization of the human mitochondrial methionyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry, 43, 9743–9754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthews D.E., Hessler,R.A., Denslow,N.D., Edwards,J.S. and O'Brien,T.W. (1982) Protein composition of the bovine mitochondrial ribosome. J. Biol. Chem., 257, 8788–8794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao H.-X. and Spremulli,L.L. (1989) Interaction of bovine mitochondrial ribosomes with messenger RNA. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 7518–7522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graves M. and Spremulli,L.L. (1983) Activity of Euglena gracilis chloroplast ribosomes with prokaryotic and eukaryotic initiation factors. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 222, 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bullard J.M., Cai,Y.-C., Zhang,Y. and Spremulli,L.L. (1999) Effects of domain exchanges between Escherichia coli and mammalian mitochondrial EF-Tu on interactions with guanine nucleotides, aminoacyl-tRNA and ribosomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1446, 102–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graves M., Breitenberger,C. and Spremulli,L.L. (1980) Euglena gracilis chloroplast ribosomes: improved isolation procedure and comparison of elongation factor specificity with prokaryotic and eukaryotic ribosomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 204, 444–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen H.U., Roll,T., Grunberg-Manago,M. and Clark,B.F. (1979) Specific interaction of initiation factor IF2 of E.coli with formylmethionyl-tRNAfMet. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 91, 1068–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mortensen K., Kildsgaard,J., Moreno,J.M.P., Steffensen,S., Egebjerg,J. and Sperling-Petersen,H. (1998) A six-domain structural model for Escherichia coli translation initiation factor 2. Characterization of twelve surface epitopes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 46, 1027–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Misselwitz R., Welfle,K., Krafft,C., Welfle,H., Brandi,L., Caserta,E. and Gualerzi,C. (1999) The fMet-tRNA binding domain of translational initiation factor IF2: role and environment of its two Cys residues. FEBS Lett., 459, 332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szkaradkiewicz K., Zuleeg,T., Limmer,S. and Sprinzl,M. (2000) Interaction of fMet-tRNAfMet and fMet-AMP with the C-terminal domain of Thermus thermophilus translation initiation factor 2. Eur. J. Biochem., 267, 4290–4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spurio R., Brandi,L., Caserta,E., Pon,C., Gualerzi,C., Misselwitz,R., Krafft,C., Welfle,K. and Welfle,H. (2000) The C-terminal subdomain (IF2 C-2) contains the entire fMet-tRNA binding site of initiation factor IF2. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 2447–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krafft C., Diehl,A., Laettig,S., Behlke,J., Heinemann,U., Pon,C.L., Gualerzi,C.O. and Welfle,H. (2000) Interaction of fMet-tRNA(fMet) with the C-terminal domain of translational initiation factor IF2 from Bacillus stearothermophilus. FEBS Lett., 471, 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumstark B.R., Spremulli,L.L., RajBhandary,U.L. and Brown,G.M. (1977) Initiation of protein synthesis without formylation in a mutant of Escherichia coli that grows in the absence of tetrahydrofolate. J. Bacteriol., 129, 457–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.RajBhandary U. and Chow,C. (1995) Initiator tRNAs and initiation of protein synthesis. In Soll,D. and RajBhandary,U. (eds), tRNA: Structure, Biosynthesis and Function. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, pp. 511–528. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sundari R.M., Stringer,E.A., Schulman,L.H. and Maitra,U. (1976) Interaction of bacterial initiation factor 2 with initiator tRNA. J. Biol. Chem., 251, 3338–3345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu X. and RajBhandary,U. (1997) Effect of the amino acid attached to Escherichia coli initiator tRNA on its affinity for the initiation factor IF2 and on the IF2 dependence of its binding to the ribosome. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 1891–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meunier S., Spurio,R., Czisch,M., Wechselberger,R., Guenneugues,M., Gualerzi,C.O. and Boelens,R. (2000) Structure of the fMet-tRNA(fMet)-binding domain of B.stearothermophilus initiation factor IF2. EMBO J., 19, 1918–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guenneugues M., Caserta,E., Brandi,L., Spurio,R., Meunier,B., Pon,C.L., Boelens,R. and Gualerzi,C.O. (2000) Mapping the fMet-tRNA binding site of initiation factor IF2. EMBO J., 19, 5233–5240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]