Abstract

The activity of DNA topoisomerase I (Top1), an enzyme that regulates DNA topology, is impacted by DNA structure alterations and by the anticancer alkaloid camptothecin (CPT). Here, we evaluated the effect of the acetaldehyde-derived DNA adduct, N2-ethyl-2′-deoxyguanosine (N2-ethyl-dG), on human Top1 nicking and closing activities. Using purified recombinant Top1, we show that Top1 nicking-closing activity remains unaffected in N2-ethyl-dG adducted oligonucleotides. However, the N2-ethyl-dG adduct enhanced CPT-induced Top1–DNA cleavage complexes depending on the relative position of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct with respect to the Top1 cleavage site. The Top1-mediated DNA religation (closing) was selectively inhibited when the N2-ethyl-dG adduct was present immediately 3′ from the Top1 site (position +1). In addition, when the N2-ethyl-dG adduct was located at the −5 position, CPT enhanced cleavage at an alternate Top1 cleavage site immediately adjacent to the adduct, which was then at position +1 relative to this new alternate Top1 site. Modeling studies suggest that the ethyl group on the N2-ethyl-dG adduct located at the 5′ end of a Top1 site (position +1) sterically blocks the dissociation of CPT from the Top1–DNA complex, thereby inhibiting further the religation (closing) reaction.

INTRODUCTION

Double-stranded DNA exhibits fluidity in its topology by fluctuating between supercoiled and relaxed states. This adaptability is advantageous in cells, where regulating the accessibility of DNA segments to facilitate cellular functions like transcription, replication and repair is of essence. The key player that aids in regulating DNA topology is the enzyme DNA topoisomerase I (Top1) (1,2). By creating a single-stranded nick in duplex DNA, Top1 unwinds supercoiled DNA. Once DNA is relaxed, Top1 reseals (or religates) the DNA nicks to which it is associated [reviewed in (1–3)].

Normally, both the forward cleavage (k1) and reverse religation (k2) reactions catalyzed by Top1 are in equilibrium, with the cleaved intermediate (referred as cleavage complex) representing a very small fraction of the Top1–DNA complexes (k2 >> k1). However, Top1 inhibitors [like camptothecin (CPT)] alter the equilibrium by inhibiting the Top1 reversal reaction (k2 < k1), resulting in DNA breaks, which if unrepaired lead to cell death (4). Structural modifications in DNA, such as abasic sites, mismatches, oxidative lesions, base methylation (O6-methyl guanine, 5-methylcytosine), base alkylations (vinyl adducts), carcinogenic adducts and DNA strand breaks have also been shown to trapTop1–DNA covalent complexes (5–10).

Alcoholic beverage consumption is strongly associated with an increased risk of cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract (11). Several lines of evidence indicate that ethanol metabolites like acetaldehyde and free radicals are predominantly responsible for alcohol-associated carcinogenesis (11–13). Acetaldehyde can react with the exocyclic amino group of the guanine moiety in 2′-deoxyguanosine and DNA leading to the formation of several different DNA adducts (14). Of these, the most well studied and biologically significant is N2-ethyl-2′-deoxyguanosine (N2-ethyl-dG) (15). This adduct has been shown to form in the livers of mice exposed to ethanol in the drinking water (16) and was also detected in DNA isolated from white blood cells obtained from human alcoholics (17).

N2-ethyl-dG adducts can be detected in urine samples from human volunteers that had not consumed alcohol for 1 week prior to analysis (18), suggesting that it can form in the body from endogenously generated acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde is produced endogenously during threonine catabolism (19), and this pathway is enhanced in non-alcoholic liver injury (20). These considerations suggest that the formation of N2-ethyl-dG adducts may not be limited to the tissues of individuals who abuse alcohol.

In view of previous data showing that benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide DNA adducts on the N2 position of guanine can trap Top1 (5,6), the initial goal of the present study was to evaluate the effect of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct on Top1 nicking-closing activity. For this purpose, we synthesized oligonucleotides with N2-ethyl-dG adducts at selected positions relative to a normal Top1 cleavage site. We studied the effect of the N2-ethyl-dG adducts at these different positions on the formation and religation of Top1 cleavage complexes. Secondly, the ability of these adduct in altering (enhancing or suppressing) the effect of the selective inhibitor of Top1, CPT (4) (see reviews at http://discover.nci.nih.gov/pommier/pommier.htm) was investigated.

Here, we show that the N2-ethyl-dG adduct by itself does not trap detectable amounts of Top1–DNA cleavage complexes. However, this adduct does enhance the effect of CPT selectively when present on the base immediately downstream from the Top1 cleavage site by inhibiting the religation (closing) reaction. Our results indicate that N2-ethyl-dG adducts enhance CPT-mediated trapping of Top1. These results are discussed in light of the recently reported crystal structures of the Top1–DNA complexes with a CPT derivative (21).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs, enzymes and chemicals

CPT was obtained from the Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD). Drug stock solutions were made in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at 10 mM. Aliquots were stored at −20°C and further dilutions were made in DMSO immediately before use. The final concentration of DMSO in the reactions did not exceed 10% (v/v).

Recombinant human Top1 was purified from TN5 insect cells (HighFive, Invitrogen Corp., San Diego, CA) using a Baculovirus construct for the N-terminus-truncated human Top1 cDNA as described previously (7). Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), dNTP [where N is A (adenosine), C (cytosine), G (guanosine) or T (thymine)], and polyacrylamide/bis were purchased from GIBCO BRL (Gaithersburg, MD) or New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Oligo quick spin columns were purchased from Roche Diagnostics Corporation (Indianapolis, IN). [α-32P]cordycepin 5′-triphosphate was purchased from DuPont-New England Nuclear (Boston, MA). The oligonucleotides were synthesized by MWG-Biotech (High Point, NC).

Synthesis of oligonucleotides containing single N2-ethyl-dG adducts

A phosphoramidite containing N2-ethyl-dG adduct was synthesized by Glen Research Inc. (Sterling, VA). Oligonucleotides containing the lesion and control oligonucleotides were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems 394 DNA/RNA synthesizer using standard methods, followed by overnight deprotection in 28% ammonium hydroxide at 50°C. Oligonucleotides were lyophilized and purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

The presence of the lesion in oligonucleotides was confirmed by digestion with venom phosphodiesterase and alkaline phosphatase, followed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. A sample of pure N2-ethyl-dG was chemically synthesized essentially as described previously (14) and purified by HPLC for using as a standard in both methods. The presence of the lesion in the oligonucleotides was additionally confirmed using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (Midland Certified Reagent Company, Midland, TX).

Top1 reactions

Single-stranded oligonucleotides were 3′-labeled with [α-32P]cordycepin and TdT as described. Labeling mixtures were subsequently centrifuged through mini quick spin Oligo columns (Roche Diagnostics Corporation) to remove the unincorporated [α-32P]cordycepin. Annealing to the unlabeled complementary strand was performed in 1× annealing buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.8, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) by heating the reaction mixtures to 95°C for 5 min, followed by slow cooling to room temperature.

For Top1 cleavage assays, labeled oligonucleotides (∼50 fmol/reaction) were incubated with 5 ng of recombinant Top1 with or without drug at 25°C in 10 μl reaction buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 15 μg/ml BSA, final concentrations). The reactions were stopped by adding SDS (0.5% final concentration). For reversal experiments, the SDS stop was preceded by the addition of NaCl to a final concentration of 0.35 M followed by incubation for varying time points (min) at 25°C.

To the reaction mixtures, 3.3 vol of Maxam Gilbert loading buffer (80% formamide, 10 mM NaOH, 1 mM NaEDTA, 0.1% xylene cyanol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue, pH 8.0) was added. Aliquots were separated in 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels (7 M urea) in 1× TBE (89 mM Tris-borate, 2 mM EDTA) for 2 h at 40 V/cm at 50°C.

Imaging was performed using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Quantification of the labeled DNA bands was performed using the software ImageQuant (that calculates the intensity of the band/product within a given area). Then the percent cleavage of product was calculated relative to the total product + substrate.

Calculation of the cleavage (k1) and religation (k2) rate constants for ethyl adduct- and CPT-induced Top1-mediated DNA cleavage

Top1 catalyzes two transesterification reactions. The first reaction results in the formation of a covalent enzyme–DNA complex, the rate of which is denoted as k1. The second reaction religates the ends of the broken DNA, and the rate of this reverse reaction is denoted as k2. Under normal conditions, the Top1-mediated cleavage is transient (k2 >> k1). CPT traps the Top1 cleavage complex by inhibiting religation reversibility (i.e. by decreasing k2). This can be schematically represented as:

At steady state,

![]()

In the presence of salt (NaCl), assuming that k1 = 0, the time taken for half of the cleaved product to reverse (T1/2) was calculated from the semi-log plot of the percentage of cleavage product remaining after salt reversal (see Figures 2D and 3D).

Figure 2.

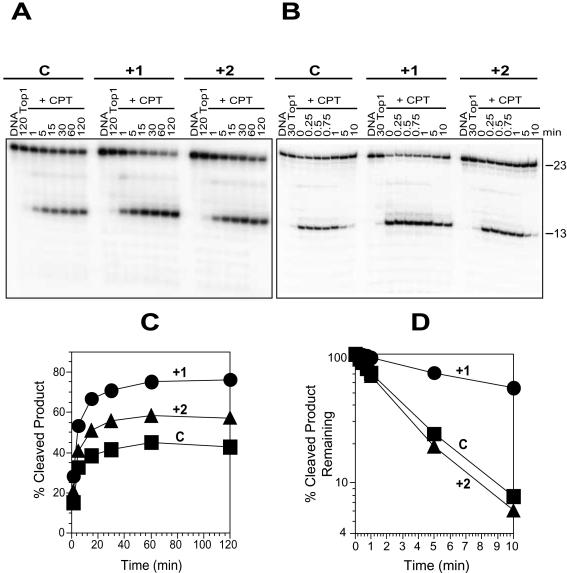

Selective enhancement of CPT-induced trapping of Top1 by N2-ethyl-dG adducts at the +1 position relative to the Top1–DNA cleavage site. (A) The labeled control (C) oligonucleotide as in Figure 1B was reacted with Top1 in the absence of drug for 120 min (120 Top1) or in the presence of 1 μM CPT (+CPT) at 25°C for the indicated time points (min). Similar reactions were carried out with the adducted oligonucleotides (+1 and +2). (B) Using the same 3′-labeled oligonucleotides as in (A), Top1 reactions were carried out at 25°C for 30 min in the absence of drug (30 Top1) or in the presence of 1 μM CPT (+CPT). Reactions were stopped before (0) and after salt reversal in 0.35 M NaCl at 25°C for the indicated time periods (min). Numbers 23 and 13 indicate the size of the 3′-labeled oligonucleotide substrate and the Top1-mediated DNA fragment produced with CPT respectively. (C) CPT-induced Top1-mediated cleavage products obtained for control (square), adducted +1 (circle) and +2 (triangle) oligonucleotides from (A) were quantified and represented graphically. (D) Reactions carried out as in (B) were quantified and the percentage of Top1-mediated cleavage products remaining after salt reversal for control (square), adducted +1 (circle) and +2 (triangle) oligonucleotides were represented as semi-log plots. Values are normalized to the drug-induced cleavage product remaining at time 0 taken as 100%. Computation of the kinetic constants is shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

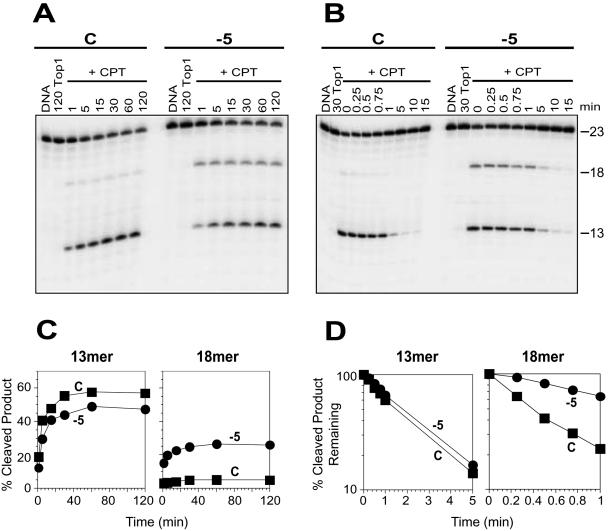

Selective enhancement of CPT-induced trapping of Top1 at a secondary site by the N2-ethyl-dG adduct at the position −5. (A) Top1 reactions were carried out as in Figure 2A with the 3′-labeled unadducted (C) and adducted oligonucleotide (−5) in the absence of drug for 120 min (120 Top1) or in the presence of 1 μM CPT (+CPT) at 25°C for the indicated times (min). (B) Using the same oligonucleotides as in (A), the reactions were carried out with Top1 at 25°C for 30 min in the absence (30 Top1) or in the presence of 1 μM CPT (+CPT). Reactions were stopped before (0) and after reversal at 25°C for the indicated time periods (min). Numbers 23, 18 and 13 indicate the size of the 3′-labeled oligonucleotide substrate and the Top1-mediated DNA fragments induced by CPT, respectively. (C) CPT-induced Top1-mediated 13 and 18mer cleavage products obtained using control (square) and adducted −5 (circle) oligonucleotides from (A) were quantified and represented graphically. (D) Reactions carried out in (B) were quantified and the percentage of CPT-induced Top1-mediated 13mer and 18mer cleavage products remaining after salt reversal at 25°C in the control (square) and adducted −5 (circle) oligonucleotides were represented as semi-log plots. Values are normalized to the drug-induced cleavage product remaining at time 0 taken as 100%. Computation of the kinetic constants is shown in Table 2.

The religation rate constant k2 was calculated as:

![]()

The cleavage rate constant k1 was then calculated as:

![]()

where r is the fraction of cleavage product at the plateau (see Figures 2C and 3C). Derivations of these equations are described in detail previously (22).

RESULTS

The N2-ethyl-dG adduct enhances CPT-induced trapping of Top1

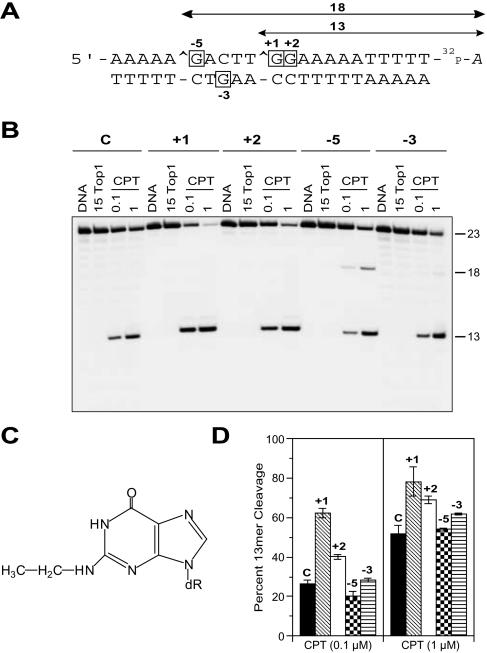

To assess whether the N2-ethyl-dG adduct (Figure 1C) influences the nicking-closing activity of Top1, we used a labeled 23 bp oligonucleotide (sequence shown in Figure 1A) containing a unique Top1 site, which can be trapped by CPT yielding a 13mer product (5,6). Additional oligonucleotides were synthesized which contained a single N2-ethyl adduct (structure shown in Figure 1C) at the position +1, +2 or −5 relative to the Top1–DNA cleavage site on the top (scissile) strand, or at the position −3 on the bottom strand. As shown in Figure 1B, no effect of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct on Top1 cleavage was observed in the absence of CPT irrespective of their location relative to the Top1–DNA cleavage site (Figure 1B, 15 Top1).

Figure 1.

Enhancement of CPT-induced Top1-mediated DNA cleavage by N2-ethyl-dG adducts at specific positions. (A) Sequence of the 22mer oligonucleotide used for this study with the 3′ radiolabel (cordycepin indicated by 32P-A) on the scissile strand of the duplex. Algebraic numbers represent the four modified oligonucleotides studied, where the numbered dG is adducted to an ethyl group (C). The modified bases corresponding to these positions within the oligonucleotides are indicated as boxed bases. The Top1-mediated DNA cleavage site is indicated by a caret (∧). (B) The control (C) oligonucleotide was reacted for 15 min at 25°C with Top1 in the absence of drug (15 Top1) or in the presence of 0.1 or 1 μM CPT (CPT). Similar reactions were carried out using each of the four adducted (+1, +2, −5 and −3) duplex oligonucleotides. Numbers 23, 18 and 13 indicate the size of the 3′-labeled oligonucleotide and the Top1-mediated DNA fragments, respectively. (C) Chemical structure of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct. (D) Quantitation of the Top1-mediated cleavage products obtained with CPT (0.1 and 1 μM) (mean ± SD of three independent experiments).

To further evaluate the possible influence of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct on the cleavage of the DNA by Top1, we next tested the effect of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct on Top1 in the presence of CPT. Trapping of Top1 induced by CPT was enhanced by the presence of N2-ethyl-dG adduct depending on its location relative to the Top1–DNA cleavage site. When present 1 bp downstream to the cleavage site position (+1), the enhancement of Top1-trapping was the most significant, by about two times that in the control DNA. In contrast, placement of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct in either the +2 or −5 positions of the scissile strand or in the −3 position of the non-scissile strand had little effect on CPT-induced Top1 trapping. The N2-ethyl-dG adduct at the −5 position enhanced cleavage at an alternate site yielding an 18mer product (see Figure 1B). Based on these observations, we conclude that the N2-ethyl-dG adduct by itself does not affect the nicking-closing activity of Top1, but the adduct does enhance the CPT-induced Top1 cleavage when located on the +1 base relative to a Top1–DNA cleavage site.

The N2-ethyl-dG adduct at the +1 position enhances CPT-induced Top1 cleavage by inhibiting the Top1-mediated reversal (religation) reaction

Of the two reactions (single-strand DNA cleavage and religation) catalyzed by Top1, prior studies have shown that CPT traps Top1–DNA complexes by inhibiting the religation reaction (23–27). To determine the Top1 reaction influenced by N2-ethyl-dG adduct that results in enhancing the CPT effect, we carried out a kinetic analysis of cleavage and religation of the CPT–Top1–DNA cleavage complexes with adducts located downstream (+1 and +2) of the cleavage site (Figure 2).

As shown in Figure 2A, in the presence of N2-ethyl-dG adduct, the CPT-mediated trapping of Top1 increased with time and reached a steady state as it does in the control. The steady state cleavage for the +1 adduct was almost twice that of the control, while the effect of the +2 adduct was only marginally greater than control (Figure 2C). Upon addition of salt that prevents Top1 from nicking the DNA, the Top1 cleavage complexes reverse (26,28). The CPT–Top1–DNA complexes formed in the +1 adduct oligonucleotide reversed markedly slower than either the control or the +2 adduct (see Figure 2B). Even after 10 min, more than 50% of the complexes persisted (Figure 2C), implying that the +1 N2-ethyl-dG adduct is inhibiting the reversal reaction of the CPT-Top1–DNA complexes.

An evaluation of the rates of the forward cleavage (k1) and reverse religation (k2) reactions of CPT–Top1–DNA complexes in the presence of the +1 and +2 adducts (Table 1) shows that k1 is not significantly altered in the presence of adduct. However, k2 in the +1 adduct (0.07) was reduced by more than 5 times, as compared to the control (0.37) and the +2 adduct (0.42), which were about the same. These experiments indicate that the enhancing effect of the +1 N2-ethyl-dG adduct on CPT-mediated trapping of Top1 is due to a stabilization of the CPT–Top1–DNA complexes.

Table 1. Cleavage and religation rate constants of CPT-induced DNA cleavage products in Control (C) and the N2-ethyl-dG adducted 23mer oligonucleotides (+1 and +2).

| C | +1 | +2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1/2 (min) | 1.87 ± 0.23 | 9.73 ± 1.52 | 1.72 ± 0.36 |

| k2 (min−1) | 0.37 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.42 ± 0.1 |

| k1 (min−1) | 0.65 ± 0.23 | 0.71 ± 0.16 | 1.2 ± 0.26 |

| r | 0.59 ± 0.1 | 0.85 ± 0.06 | 0.69 ± 0.03 |

T1/2, religation rate half-life determined from the salt reversal experiments (see Figure 2D); k2, religation rate constant determined from T1/2; k1, cleavage rate constant (see Materials and Methods); r: fraction of cleavage product at the plateau (see Figure 2C).

The values are an average of three independent experiments.

Enhancement of a secondary CPT–Top1–DNA cleavage site by the N2-ethyl-dG adduct located upstream (−5) to the primary Top1 cleavage site

From Figure 1B, it is evident that the −5 adduct does not alter the trapping of Top1 by CPT at the primary site that yields a 13mer product, but does enhance cleavage at a secondary site yielding an 18mer product (see Figure 1A). Kinetic analyses of the cleavage and religation reactions were carried out to identify the mechanism of Top1 cleavage enhancement by the −5 adduct.

Figure 3 is a comparison of the differential effects of the −5 N2-ethyl-dG adduct on the two Top1 sites generating the 13 and 18mer cleavage products. From Figure 3A and C, the amount of the 13mer product was comparable in the −5 adducted and unadducted (C) oligonucleotides, and the reversal kinetics of the 13mer product were comparable (Figure 3B and D and Table 2) in the control and −5 oligonucleotides. However, with regard to the 18mer product, the steady state level of CPT–Top1–DNA complexes was increased to ∼5-fold in the −5 oligonucleotide as compared to the unadducted control (C) (Table 2). This enhancement was related to about a 5-fold reduction of reversal rate of the 18mer product in the −5 adducted oligonucleotide (see Table 2).

Table 2. Cleavage and religation rate constants of the 13 and 18mer Top1–DNA cleavage products trapped by CPT in Control (C) and N2-ethyl-dG adducted (−5) oligonucleotide.

| 13mer product | 18mer product | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | −5 | C | −5 | |

| T1/2 (min) | 1.87 ± 0.23 | 1.88 ± 0.33 | 0.43 ± 0.1 | 1.83 ± 0.33 |

| k2 (min−1) | 0.37 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 1.69 ± 0.36 | 0.38 ± 0.07 |

| k1 (min−1) | 0.65 ± 0.23 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.15 ± 0.04 |

| r | 0.59 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.02 |

T1/2, religation rate half-life determined from the salt reversal experiments (see Figure 3D); k2, religation rate constant determined from T1/2; k1, cleavage rate constant (see Materials and Methods); r, fraction of cleavage product at the plateau (see Figure 3C).

The values are an average of three independent experiments.

It is notable that the −5 N2-ethyl-dG adduct is on the base immediately downstream (3′) from the 18mer, and therefore is at the ‘+1’ position with respect to this secondary Top1 cleavage site.

Molecular modeling of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct at the +1 position

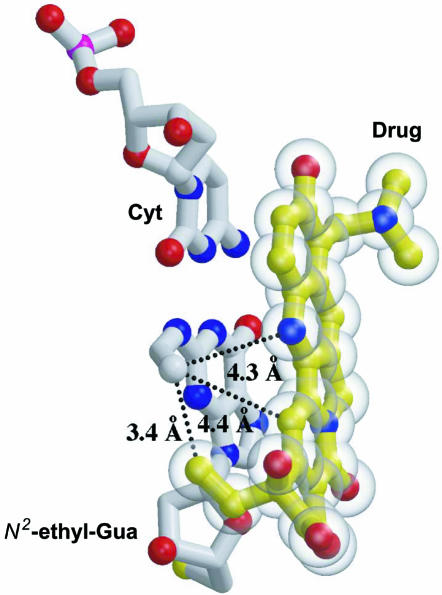

To gain insight into the molecular interactions that could account for the enhanced trapping of CPT–Top1–DNA complexes by the N2-ethyl-dG adduct at the +1 position, molecular modeling was carried out. An N2-ethyl-dG adduct was modeled (see Figure 4) into the guanine base at the +1 position of the scissile strand of the crystal structure of human Top1 in complex with DNA and a CPT derivative (21).

Figure 4.

Molecular modeling of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct at the +1 position. The N2-ethyl-guanine, modeled into the guanine base (white) at the +1 position of the scissile DNA strand of the human TopI–DNA–topotecan crystal structure (21), forms a 3.4 Å Van der Waals contact with the ethyl group of topotecan (yellow). This N2-ethyl-dG adduct also comes within 4.3 and 4.4 Å of the N1 and C14 positions on the drug. Each of these interactions is likely to block the dissociation of the drug from the covalent Top1–DNA complex.

The terminal methyl of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct forms a 3.4 Å Van der Waals contact with the CPT ethyl group at the position 20 on the drug. The ethyl adduct also comes within 4.3 and 4.4 Å of the C14 and N1 positions, respectively, on the central rings of the drug. Van der Waals interactions between the adduct and the drug is likely to increase the affinity of drug for an enzyme–DNA complex containing this adduct at the scissile strand +1 position.

DISCUSSION

As Top1 is an abundant and essential nuclear enzyme (1), in the present work, we evaluated the effect of theN2-ethyl-dG adduct on Top1 activity in vitro. We observed that the adduct does not by itself trap Top1 cleavage complexes to any significant extent. This is in contrast to the N2-benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide–dG adducts (7,10) that act both as effective inhibitors of Top1 cleavage and religation reactions depending on the position of the adduct. Although both the benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide and the N2-ethyl-dG adducts occupy the DNA minor groove from the N2-dG position, the difference in their effects on Top1 is probably due to the difference in adduct size. While the N2-ethyl-dG adduct is relatively small (see Figure 1C), the benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide adducts are significantly bulkier (7), which is probably why they interfere with Top1 activity.

Trapping of Top1 by CPT was enhanced in the presence of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct (see Figure 1). The ethyl adduct-mediated enhancement of CPT-induced cleavage was specifically observed when the adduct was located at the (+1) position relative to the site of Top1 cleavage (Figure 2). This was observed for two of the five adducts examined (−5 and +1). In both cases, the N2-ethyl-dG adduct was immediately flanking the cleavage site at the +1 position (5′ end of the cleaved DNA). Analysis of the kinetics of Top1 reactions demonstrated inhibition of the reversal (religation) reaction (Figures 2D and 3D and Tables 1 and 2). We interpret this finding as a stabilization of CPT within the Top1–DNA complex by (+1) N2-ethyl-dG adduct. As no structural data are presently available for the Top1–DNA–CPT complex, we used the published crystal structure of the Top1–DNA–Topotecan complex (21) to understand how the (+1) N2-ethyl-dG adduct could stabilize CPT within the Top1–DNA complex. The binding of topotecan in the Top1–DNA complex appears very similar to the binding of CPT (data not shown). As modeled in Figure 4, the terminal methyl of the N2-ethyl-dG adduct forms a 3.4 Å Van der Waals contact with the ethyl group on the drug. Such an interaction is likely to increase slightly the affinity of the drug for an enzyme–DNA complex containing this adduct at the scissile strand +1 position. The ethyl adduct also comes within 4.3 and 4.4 Å of the N1 and C14 positions, respectively, on the central rings of the drug. While this is not within Van der Waals contact distance, it does highlight an additional role that this adduct might play in stabilizing the Top1–DNA–drug ternary complex. An entrance and exit path for the drug into the enzyme–DNA complex was recently proposed based on an available channel from the surface of the enzyme to the DNA (29). The ethyl adduct at the N2 position in this guanine sterically blocks this pathway, and thus would be expected to slow dissociation of the drug from the enzyme–DNA complex. Indeed, as described above and shown in Figure 2 and Table 1, an N2-ethyl-dG adduct at the (+1) site impacts the dissociation of CPT-trapped Top1 cleavage complexes rather than its association with the Top1–DNA complexes.

From our results, we conclude that the N2-ethyl-dG adduct permits Top1-mediated DNA cleavage but that depending on its position in the DNA sequence relative to the Top1 cleavage site, in the presence of CPT, the N2-ethyl-dG adduct can inhibit religation, resulting in accumulation (trapping) of the Top1–DNA cleavage complex. Based on the inhibition of the religation reaction and the observed interactions in the model, we conclude that the enhancement of CPT-mediated Top1 cleavage complexes by the N2-ethyl-dG adduct most likely results from a combination of conformational and electrostatic effects. These results can be interpreted in light of the recently published crystal structures of Top1–DNA complexes (30).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang J.C. (2002) Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 3, 430–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Champoux J.J. (2001) DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 70, 369–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keck J.L. and Berger,J.M. (1999) Enzymes that push DNA around. Nature Struct. Biol., 6, 900–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pommier Y., Redon,C., Rao,V.A., Seiler,J.A., Sordet,O., Takemura,H., Antony,S., Meng,L., Liao,Z., Kohlhagen,G. et al. (2003) Repair of and checkpoint response to topoisomerase I-mediated DNA damage. Mutat. Res., 532, 173–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pommier Y., Laco,G.S., Kohlhagen,G., Sayer,J.M., Kroth,H. and Jerina,D.M. (2000) Position-specific trapping of topoisomerase I-DNA cleavage complexes by intercalated benzo[a]-pyrene diol epoxide adducts at the 6-amino group of adenine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 10739–10744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pommier Y., Kohlhagen,G., Pourquier,P., Sayer,J.M., Kroth,H. and Jerina,D.M. (2000) Benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide adducts in DNA are potent suppressors of a normal topoisomerase I cleavage site and powerful inducers of other topoisomerase I cleavages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 2040–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pommier Y., Kohlhagen,G., Laco,G.S., Kroth,H., Sayer,J.M. and Jerina,D.M. (2002) Different effects on human topoisomerase I by minor groove and intercalated deoxyguanosine adducts derived from two polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon diol epoxides at or near a normal cleavage site. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 13666–13672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pourquier P., Ueng,L.M., Kohlhagen,G., Mazumder,A., Gupta,M., Kohn,K.W. and Pommier,Y. (1997) Effects of uracil incorporation, DNA mismatches, and abasic sites on cleavage and religation activities of mammalian topoisomerase I. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 7792–7796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pourquier P., Bjornsti,M.A. and Pommier,Y. (1998) Induction of topoisomerase I cleavage complexes by the vinyl chloride adduct 1,N6-ethenoadenine. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 27245–27249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian L., Sayer,J.M., Kroth,H., Kalena,G., Jerina,D.M. and Shuman,S. (2003) Benzo[a]pyrene-dG adduct interference illuminates the interface of vaccinia topoisomerase with the DNA minor groove. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 9905–9911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poschl G. and Seitz,H.K. (2004) Alcohol and cancer. Alcohol Alcohol., 39, 155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks P.J. (1997) DNA damage, DNA repair, and alcoholtoxicity—a review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res., 21, 1073–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quertemont E. and Tambour,S. (2004) Is ethanol a pro-drug? The role of acetaldehyde in the central effects of ethanol. Trends Pharmacol. Sci., 25, 130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hecht S.S., McIntee,E.J. and Wang,M. (2001) New DNA adducts of crotonaldehyde and acetaldehyde. Toxicology, 166, 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaca C.E., Fang,J.L., Mutanen,M. and Valsta,L. (1995) 32P-postlabelling determination of DNA adducts of malonaldehyde in humans: total white blood cells and breast tissue. Carcinogenesis, 16, 1847–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang J.L. and Vaca,C.E. (1995) Development of a 32P-postlabelling method for the analysis of adducts arising through the reaction of acetaldehyde with 2′-deoxyguanosine-3′-monophosphate and DNA. Carcinogenesis, 16, 2177–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang J.L. and Vaca,C.E. (1997) Detection of DNA adducts of acetaldehyde in peripheral white blood cells of alcohol abusers. Carcinogenesis, 18, 627–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda T., Terashima,I., Matsumoto,Y., Yabushita,H., Matsui,S. and Shibutani,S. (1999) Effective utilization of N2-ethyl-2′-deoxyguanosine triphosphate during DNA synthesis catalyzed by mammalian replicative DNA polymerases. Biochemistry, 38, 929–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa H., Gomi,T. and Fujioka,M. (2000) Serine hydroxymethyltransferase and threonine aldolase: are they identical? Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol., 32, 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma X.L., Baraona,E., Hernandez-Munoz,R. and Lieber,C.S. (1989) High levels of acetaldehyde in nonalcoholic liver injury after threonine or ethanol administration. Hepatology, 10, 933–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staker B.L., Hjerrild,K., Feese,M.D., Behnke,C.A., Burgin,A.B.,Jr and Stewart,L. (2002) The mechanism of topoisomerase I poisoning by a camptothecin analog. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 15387–15392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antony S., Jayaraman,M., Laco,G., Kohlhagen,G., Kohn,K.W., Cushman,M. and Pommier,Y. (2003) Differential induction of topoisomerase I-DNA cleavage complexes by the indenoisoquinoline MJ-III-65 (NSC 706744) and camptothecin: base sequence analysis and activity against camptothecin-resistant topoisomerases I. Cancer Res., 63, 7428–7435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kjeldsen E., Svejstrup,J.Q., Gromova,II, Alsner,J. and Westergaard,O. (1992) Camptothecin inhibits both the cleavage and religation reactions of eukaryotic DNA topoisomerase I. J. Mol. Biol., 228, 1025–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsiang Y.H., Hertzberg,R., Hecht,S. and Liu,L.F. (1985)Camptothecin induces protein-linked DNA breaks via mammalian DNA topoisomerase I. J. Biol. Chem., 260, 14873–14878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaxel C., Capranico,G., Kerrigan,D., Kohn,K.W. and Pommier,Y. (1991) Effect of local DNA sequence on topoisomerase I cleavage in the presence or absence of camptothecin. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 20418–20423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanizawa A., Kohn,K.W., Kohlhagen,G., Leteurtre,F. and Pommier,Y. (1995) Differential stabilization of eukaryotic DNA topoisomerase I cleavable complexes by camptothecin derivatives. Biochemistry, 34, 7200–7206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter S.E. and Champoux,J.J. (1989) The basis for camptothecin enhancement of DNA breakage by eukaryotic topoisomerase I. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 8521–8532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valenti M., Nieves-Neira,W., Kohlhagen,G., Kohn,K.W., Wall,M.E., Wani,M.C. and Pommier,Y. (1997) Novel 7-alkyl methylenedioxy-camptothecin derivatives exhibit increased cytotoxicity and induce persistent cleavable complexes both with purified mammalian topoisomerase I and in human colon carcinoma SW620 cells. Mol. Pharmacol., 52, 82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chrencik J.E., Burgin,A.B., Pommier,Y., Stewart,L. and Redinbo,M.R. (2003) Structural impact of the leukemia drug 1-beta-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine (Ara-C) on the covalent humantopoisomerase I-DNA complex. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 12461–12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Redinbo M.R., Champoux,J.J. and Hol,W.G. (2000) Novel insights into catalytic mechanism from a crystal structure of human topoisomerase I in complex with DNA. Biochemistry, 39, 6832–6840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]