Introduction

Humans rely heavily on the corticospinal tract (CST) for skilled arm and hand movements1,2, and injury to the CST is largely responsible for impairments following brain and spinal cord injury2–5. Rodents are commonly used to model CST injury because they are relatively dexterous, and they balance the cost and ethical considerations for injury and repair research. However, current tests of rat motor function are insensitive to CST injuries6. This is partly because rats rely less strongly on the CST and more strongly on brain stem descending systems7 to perform skilled tasks compared to humans2. Further, the deficits produced by CST injury may not be detected by current behavioral tests because they do not directly measure movements that are most impaired. We hypothesized that quantifying supination, the ability to rotate the hand from palm down to palm up, would allow detection of deficits in skilled forelimb movements after CST injury.

Supination is an important hand function that relies on the CST. Among arm and hand impairments caused by CST injury, loss of hand supination is among the most severe and disabling8. Supination is critical for people’s daily functions such as unlocking or opening doors. But more importantly, supination brings the hand into a position for manipulation. This likely explains why out of all individual arm and hand movements impaired by injury, supination loss most strongly predicts loss of hand function9–11. Clinically, testing for “pronator drift”, evidence of supination loss, is a sensitive and specific sign or CST injury12. Finally, supination is selectively impaired in rats as well. Previous studies in our lab13,14 and others15,16 demonstrate that CST injury results in a greater loss of forelimb supination compared to other forelimb movements.

Current tests of rat forelimb supination are either qualitative or impractical. The single pellet reaching task, a standard forelimb task in rats, measures retrieval rate quantitatively and the quality of movement elements of reach qualitatively. While CST injury does not impair pellet retrieval17, supination is qualitatively impaired15,18. Further, given the labor intensive and subjective nature of the single pellet reaching task has made researchers hesitant to adopt this technique widely19. Similarly, we have also quantified the large loss of supination after lesion of the pyramidal tract14. However, we had to measure paw angle from video recording using frame-by-frame measurement, which is both labor-intensive and subjective.

To test the hypothesis that supination loss is a good measure of CST function in rats, we compared performance of the single pellet reaching task and a novel knob supination task. We tested rats before and after cutting the pyramids at the level of the medulla (called pyramidotomy), which interrupts both the direct corticospinal projections and the projections to the lower medulla, including reticular formation. We found that following such lesion, supination was more impaired than other reaching movements. We followed the performance of the rats for 6 weeks after injury and found that animals showed partial recovery of supination function, similar to human motor recovery after CST injury. We also inactivated motor cortex using different concentrations of the GABAA-agonist muscimol. This pharmacological approach allows us to test the effects of different doses, corresponding to increased loss of motor cortex function. We found that inactivation caused a dose-dependent loss of supination that outstripped the loss of other components of reach. In both models—injury and inactivation—the knob supination task was highly sensitive to loss of function of the pyramidal tract and motor cortex. Thus, measuring supination in rats with the knob supination task allows interrogation of CST function and recovery that has not been possible with current behavior tests.

Methods

Overview

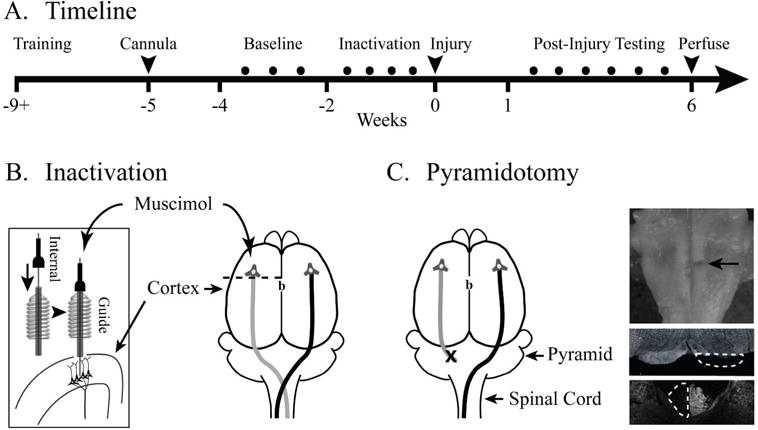

A timeline of the experimental protocol is shown in Fig. 1A. Rats were trained and tested on the knob supination task and the single pellet reaching task (Fig. 1A). After the rats reached criterion performance on each task, CST function was perturbed with one or both interventions. To test the sensitivity of the tests to the degree of motor cortex inactivation, we infused two different doses of the GABAA agonist muscimol into the forelimb area of motor cortex (Fig. 1B). To test dependence of the task on the pyramidal tract, the tract was lesioned at the medulla (Fig. 1C). Performance of each task was measured before pyramidotomy and each week after for 6 weeks.

Figure 1.

Experimental schema. (A) Experimental timeline. (B) After four weeks of behavioral training, animals were implanted with a cannula for muscimol inactivation. Anterior-posterior position of the cannula is 1.5mm anterior to bregma (shown as ‘b’) and medio-lateral position was 2.5mm lateral. The cannula consisted of an outer guide cannula positioned at the pia surface through which an internal cannula was placed during inactivation 1.5mm deep to the pia to target layer 5 of motor cortex. (C) The CST was lesioned by cutting the left pyramid (X). The ventral brainstem, top, shows a lesion of the left pyramid (arrow). A cross section through the injury site, middle, confirmed the complete lesion of the left pyramid (interrupted line). In select cases, lesion was confirmed by PKC gamma immunohistochemistry of the cervical spinal cord, bottom.

Subjects

Experiments were conducted on adult female Sprague Dawley rats (250–300g) because female rats are known to be better at task acquisition and hence require less time to train to criterion20. We trained 14 animals for this study, out of which 6 were trained in the knob task only, 4 were trained in the pellet reaching task only, and the remaining 4 were trained on both tasks. We chose to train fewer animals on the pellet reaching task compared to the knob task since there are several previous studies on the pellet reaching task21–23. The distributions of animals in the pyramidotomy and inactivation experiments are shown in the legends of the pertinent figures. Each animal is identified with individual symbols in the figures for further clarification. The timeline (Fig. 1A) is for rats trained and tested on both tasks. The rats were housed in standard conditions with reversed 12h dark: 12h light cycle; all training and testing was performed during the dark cycle with lights kept as low as possible. Animals were initially food restricted to a maximum 85% of their normal body weight. After the initial restriction, body weight was maintained to grow along their normal weight curve. All housing and procedures were approved by the Institute Animal Care and Use Committee at Weill Cornell Medical College.

The Knob Supination Task: Apparatus

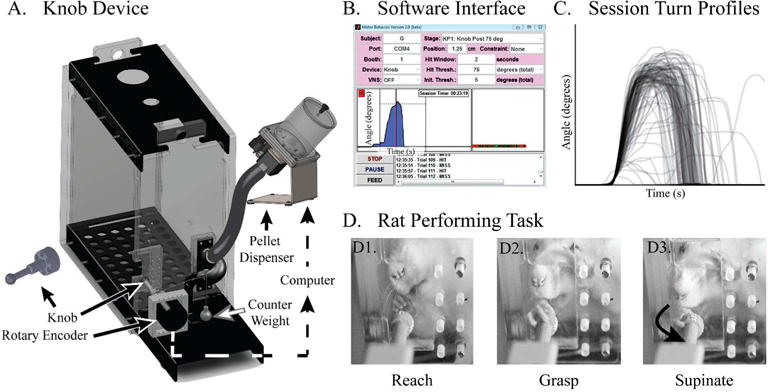

We designed the knob supination task to specifically measure forelimb supination in rodents. Rats are placed into a reaching box, and the target of the reach is a knob that must be grasped and turned in supination (Fig. 2A). The turn angle is measured with a rotary encoder (1/4th of degree resolution) that is attached to a knob. The attached computer running custom software captures turn angle at 100 Hz and sets the reward parameters (Fig. 2B). If a rat turns the knob beyond a user-defined threshold, the computer instantaneously provides an audio-feedback with attached speaker and simultaneously triggers the feeder to dispense a pellet (45 mg; Bio-Serv; Flemington, NJ). Thus, the system immediately rewards the rat for performing supination. The automated nature of the task facilitates training and testing, while the continuous measurement of performance allows quantification of the number of trials and the kinetics of each turn. The software interface is shown in Fig. 2B, and the traces from 207 trials during a 30-minute session is shown in Fig. 2C. Figure 2D demonstrates a typical turn sequence, which is also shown in Supplemental Video 1.

Figure 2.

The knob supination task. (A) The rat is placed in a reaching box with an aperture through which it reaches to a knob that must be turned in supination. The knob is attached to a rotary encoder which measures the angle with an accuracy of ¼ of a degree. An attached computer running custom software records the knob angle at 100 Hz. If the knob is turned beyond a user-defined threshold, the computer triggers audio-feedback and a pellet dispenser to drop a food pellet reward. A counter weight (6g) provides a torque that opposes supination and prevents turning by swiping the knob. (B) The software user interface shows the different parameters that can be customized. A single supination trial captured by the device is also shown. (C) Turn profiles of all of the trials from a single 30-minute session. Each trace represents the knob angle (y-axis) over time (x-axis). (D) A rat performing the task. (D1) A rat reaches towards the knob, and (D2) grasps it with a precision grip before, (D3) turning it in supination.

To ensure the rats use forelimb supination to turn the knob, we constrained the task to prevent alternative strategies. We chose a size and smoothness that require the rat to grasp the knob with the paw rather than use its claws. We added three other constraints: 1) a stop on the knob so that it cannot be pronated, 2) counter-torque to the knob to prevent turning by swiping, and 3) a high bottom lip of the aperture to prevent rats from turning the knob by lowering their elbow. The dimensions of the box are shown in Supplemental Fig. S1.

The Knob Supination Task: Training

Ten rats were trained twice a day for 30 minutes each session. During the initial phase of training, the knob manipulandum is placed 0.5″ inside the cage wall without any counter weight. After approximately one week of highly supervised training, animals began to turn the knob independently. The knob was retracted to a final location of 0.5″ outside the inner cage wall in 0.25″ increments, and counter weight was added progressively up to 6 grams. After 2–3 weeks of training, automated adaptive training software was used to train and reward the animals. Unlike previous automated tasks that use stages24, the adaptive algorithm uses the median turn angle of the previous 10 trials as threshold for the next trial, so long as it is >90% of the previous threshold. This stage of training was largely unsupervised, with one experimenter able to monitor 4 cages simultaneously. Animals were trained to a final criterion of 75% of supination. The threshold was set to 75% and testing continued until animals achieved 75% success rate or greater across 4 consecutive sessions. The average training period was 11 ± 1.1 weeks per animal.

The Knob Supination Task: Analysis

All analysis was automated, using custom MATLAB scripts, which allowed performance to be analyzed with a few commands. The main outcome measure was the percentage of turns that reached 75 degrees of supination, which is the reward criterion. Average turn angle, latency to achieve the peak angle, and peak angular velocity of the turn were secondary outcome measures.

The Single Pellet Reaching Task: Behavior Training and Analysis

Eight rats were trained on the standard pellet reaching task, using previously published protocols25. We ended training after each animal’s success rate reached a plateau for a week; the average training period was 4.3 ± 0.8 weeks per animal. During each testing session, animals attempted to reach and retrieve 10 warm-up pellets before attempting to reach and retrieve 20 pellets for scoring (45 mg chocolate-flavored grain pellets; Bio-Serv, Flemington, NJ).

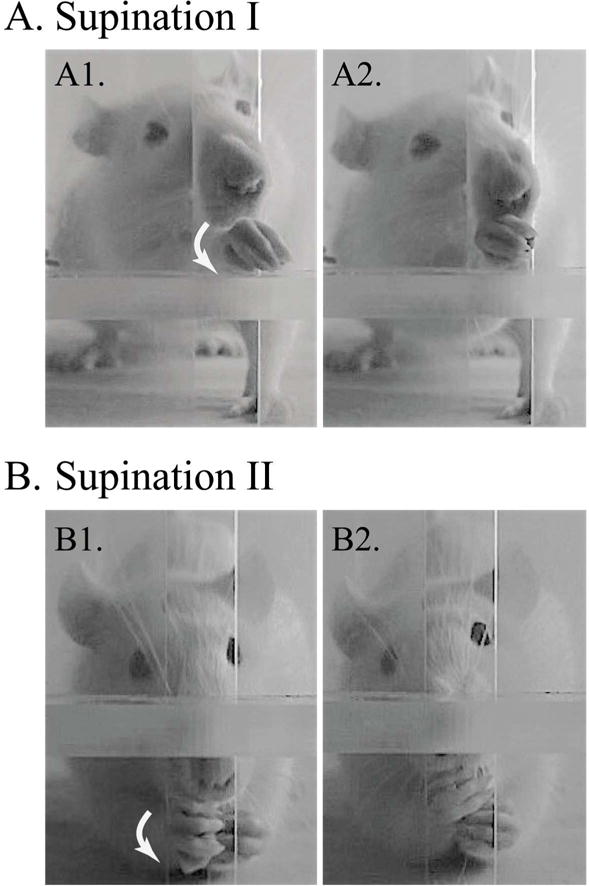

The person analyzing the video recordings was different than the person administering the test, and analysis was blinded to the condition. The experimenter administering the test was not blinded to the conditions, but we avoided any bias during training and testing by not baiting the animals until they went all the way to the back of the cage regardless of the animal’s group identity. The primary outcome measure, success rate, is calculated as retrievals/20 attempts × 100. Quality of movement was scored as ‘1’ if normal, ‘0.5’ if impaired and ‘0’ if absent for each of ten component movements25 : 1) Limb Lift, 2) Digits Close, 3) Aim, 4) Advance, 5) Digits Open, 6) Pronation, 7) Grasp, 8) Supination I, 9) Supination II, 10) Release. Out of these 10 movements, supination I and supination II were categorized as the supination components (Fig. 3), and the rest of the reaching movements were categorized as ‘other’ components.

Figure 3.

Supination during single pellet reaching task. (A) Supination I: The first frame shows the pellet grasp and paw rotating in supination (arrow), followed by second frame after supination. (B) Supination II: The first frame shows the rat sitting back while grasping a pellet and the paw rotating in supination (arrow), followed by the second frame shown after supination.

Corticospinal Injury and Validation

We performed a cut lesion of the pyramid at the level of the medulla, as in our prior studies13,14,26–28. Histology to confirm the pyramidotomy was complete was performed as in our previous studies13,26,29. The lesion site in the medulla (Fig. 1C, top inset, arrow) and the cervical spinal cord were cryosectioned at 40μm. The lesion was examined under dark field microscopy (Fig. 1C, middle inset). Any pyramidal sections that appeared ambiguous under dark field microscopy were verified for lesion completeness by immunohistochemical technique using the PKC-λ staining of the cervical spinal cord as shown29 (Fig. 1C, bottom inset).

Pharmacological Inactivation

We inactivated the caudal forelimb area of motor cortex by infusing muscimol (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat # M1523-5MG), a GABAA agonist, at two different concentrations. A cannula was implanted 1.5mm anterior and 2.5mm lateral to bregma (Fig. 1B, inset). In our published work, we found 1 μl of 0.1 μg/μl in saline produced impairment in walking similar to cutting the CST29. After 0.1 μg/μl, rats were neither able to reach and grasp nor supinate. Hence, we performed inactivations at 0.05 μg/μl (high-dose) and 0.025 μg/μl (low-dose). Both the knob task and the single pellet reaching task were performed one hour following drug infusion, as we have done previously.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS (Version 22, Chicago, IL). All figures show mean ± standard error. Data were tested for normality by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Performance of the knob task and the pellet reaching task before and after pyramidotomy was compared using related-samples Friedman’s one-way ANOVA and post-hoc tests were compared using Mann-Whitney U-Test with Bonferroni corrections, since the data were not normally distributed. The data from inactivation experiments was normally distributed, so one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used. All the data reported as mean ± SE. Significance for single comparison was set at p<0.05. For multiple comparisons, the significance level was corrected using the Bonferroni method, dividing by the number of comparisons. Thus, for 3 comparisons, the p value significance level is less than 0.05/3=0.0167.

Results

We tested the hypothesis that quantification of supination with the knob task would be a sensitive measure of pyramidal tract function. We compared performance on the pellet reaching and the knob supination tasks after two perturbations of the pyramidal tract: a cut lesion of the medullary pyramid and inactivation of motor cortex. All lesions of the pyramid were complete without intrusion into the underlying medulla (Fig. 1C). The main outcome measure for each task was success rate. In addition, we described the quality of movement for pellet reaching and measured the kinetics of knob supination.

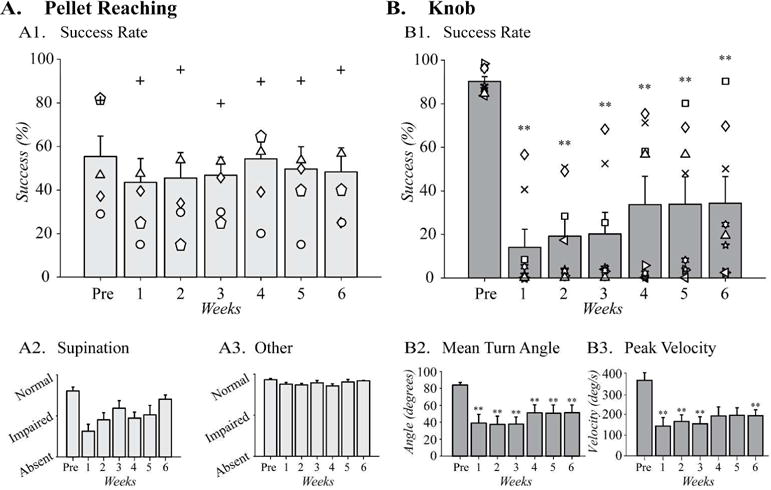

The Pellet Reaching Task is not sensitive to pyramidal tract injury

We compared performance of the single pellet reaching task before and after pyramidotomy (Fig. 4). Reaching success was the main outcome measure (Fig. 4A1). After training, rats (n=5) had an average success rate of 55.4 ± 11.1%. The success rates before and after the injury did not show significant changes for any of the six weeks post injury (Fig. 4A1, X2(6)=2.3, p=0.9).

Figure 4.

Pyramidotomy impairs supination. Ability to supinate following pyramidotomy in (A) the pellet reaching task (n = 5) and (B) the knob task (n = 8). (A1) In the pellet reaching task, success rate did not change with pyramidotomy. (A2) The quality of movement scores of the reaching movements associated with supination and the ‘other’ movements showed significant difference after injury. (B1) In the knob task, the success rate is significantly reduced for each week after CST injury and it also partially recovered during the post-injury stages. (B2) Turn angle was also significantly reduced in the knob task compared to pre-injury during all weeks post-injury and this parameter also showed partial recovery in the last 3 weeks. (B3). Peak velocity was also significantly reduced after injury in the first 3 weeks and the function partial recovered in the following 2 weeks. However, the differences were still significant at the 6th week after injury. Two animals were crossover animals between the two tasks (symbols up arrowhead and diamond). **p<0.01 by related samples Friedman’s one-way ANOVA comparing pre- and post-injury performance.

Next, we examined the effects of pyramidotomy on supination, which comprises 2 of the 10 component movements of the single pellet reaching task (Fig. 3). Supination was significantly impaired by injury (Fig. 4A2, X2(6)=17.8, p=0.007). Supination recovered to varying degrees following pyramidotomy; post-hoc comparisons, however, did not show significant differences for any of the time points. A combined analysis of the 8 other components of the reaching movements did not show significant changes after pyramidotomy (Fig. 4A3, X2(6)=11.9, p=0.07). Detailed analyses of each of the 10 movements are shown in the supplemental Fig. S1.

The Knob Supination Task is sensitive to pyramidal tract injury

Pyramidotomy caused a large decline in knob supination performance. The success of this task is quantified by the percentage of turns that reached the criterion 75° turn angle. After training, rats (n=8) achieved a success rate of 90.3 ± 2.1% (Fig. 4B1). Injury strongly and persistently impaired supination (Fig. 4B1, X2(6)=27.6, p<0.001). Following injury, the success rate fell to 14.1 ± 7.8% in the 1st week post-injury. In the following weeks, the success rate gradually improved to 34.3 ± 11.5% by the 6th week after injury. However, this recovery was still 61.9% less than the pre-injury success rate. Two animals in this task were trained and tested on both the pellet and the knob tasks (symbols triangle and diamond). The success rate declined more with the knob task than the pellet reaching task.

Pyramidotomy also produced large-scale loss of secondary outcomes, turn angle and peak velocity. Mean turn angle quantifies the degrees of supination achieved with 75° as the criterion for reward. Pyramidotomy produced a large and significant loss of mean turn angle (Fig. 4B2, X2(6)=27.4, p<0.001). Turn angle before injury was 84.8 ± 2.9°, which dropped to 38.2 ± 10.1° in the 1st week following injury, a decrease of 55.0%. The turn angle partially recovered up to 51.5 ± 9.2° by the 6th week after injury. Like turn angle, the peak velocity during the knob turn also decreased significantly following pyramidotomy (Fig. 4B3, X2(6)=20.7, p<0.01). Peak velocity of the knob turning from 365.4 ± 34.5 deg/s pre-pyramidotomy to 143.5 ± 41.6 deg/s one week after the pyramidotomy, a decrease of 60.7%. Similar to the success rate and the turn angle data, velocity of the knob turning also showed partial recovery with time. However, the recovery at the 6th week post-injury was still only 193.6 ± 27.4 deg/s, 47.1% below the pre-injury velocity; post-hoc tests indicated that these differences were significant.

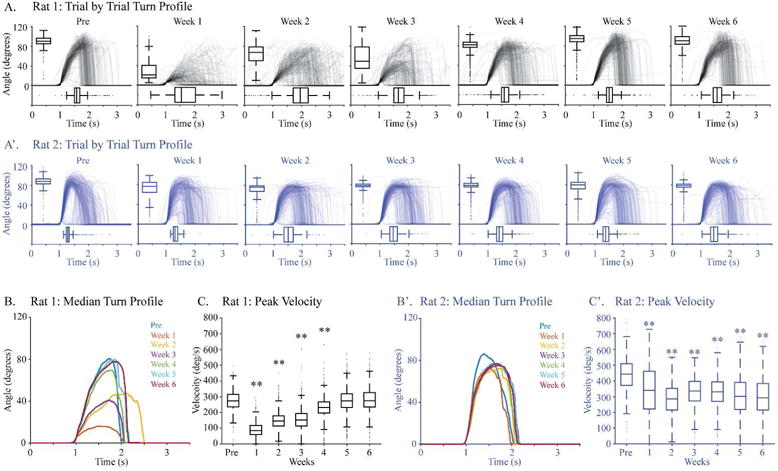

These performance measures–success rate, mean turn angle, and peak velocity–distinguish rats before and after injury for the majority of individuals and for the group. However, two rats had post-injury performance that was not very different from baseline at one or more points (Fig. 4B1, square and diamond symbols). We used knob turn kinetics to help determine whether their performance after injury constituted recovery of pre-injury performance. The kinetic data for rat 1 (Fig. 4B1, square) are shown in Fig. 5, panels A, B, and C (black). Turn profiles from before pyramidotomy and each week after are shown in Fig. 5A. In these graphs, each trace represents an individual knob supination attempt; the turn angle (Y-axis) and latency to the peak (X-axis) are quantified using box-and-whisker plots. Rat 1 shows a large decline in performance with pyramidotomy followed by gradual recovery of supination function. The medians of the turn profiles for each week for rat 1 are shown in Fig. 5B. Finally, the peak velocities are shown in Fig. 5C. By each of these measures, supination performance was severely diminished, but fully recovered by 5 weeks after injury, even though the pyramidotomy was complete (data not shown). The data for rat 2 (Fig. 4B1, diamond) are shown in Figs. 5A′, 5B′, and 5C′ (blue). This rat had a small but significant loss of success rate, turn angle, and velocity with pyramidotomy. Turns after injury achieved a lower angle and took longer to achieve the peak angle, creating an outsized decline in velocity. In addition, each of these measures was more variable than before injury.

Figure 5.

Knob kinetics. The turn profiles and kinetics for two rats: rat 1 (A) and rat 2 (B). (A) Turn profiles for rat 1 (Fig. 4B1; square symbol) for each week before and after injury indicated immediate decline of function and near full recovery by 6th week. (B) The median waveforms for each week fare colored differently. (C) Peak velocity for rat 1 showed significant differences in the first 4 weeks only. (A′) Turn profiles for rat 2 (Fig. 4B; diamond symbol) for each week before and after injury indicated small but persistent decline of function after pyramidotomy. (B′) The median waveforms for each week for rat 2 in different colors. (C′) Changes in the peak velocity for rat 2 showed significant differences for every week after injury.

Motor Cortex Inactivation in the Single Pellet Reaching Task

We tested whether pharmacological inactivation of motor cortex at two different doses caused proportionate changes in forelimb function. In dose-finding studies, we found that the dose we previously used29 (0.1 μg in 1 μL of saline) caused complete inability to supinate the knob (data not shown), so we decreased the dose to 0.05 μg/μL (high-dose) and 0.025 μg/μL (low-dose).

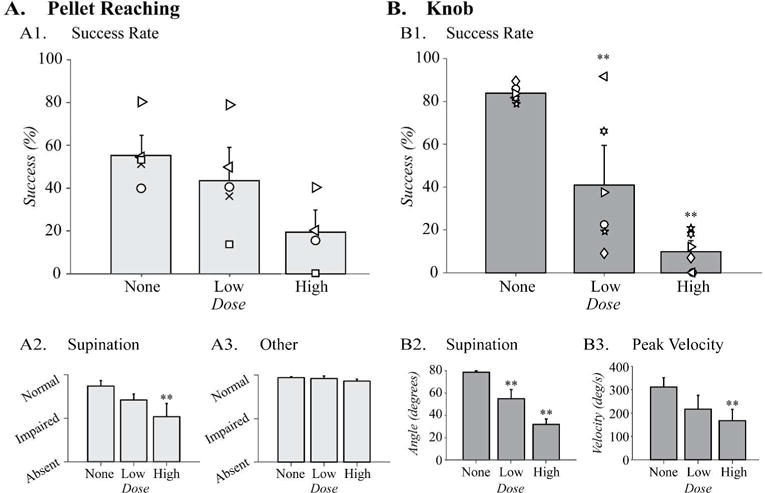

Motor cortex inactivation did not significantly decrease pellet reaching success. The animals were 55.3 ± 7.4% successful during baseline testing which decreased to 41.9 ± 13.5% with low-dose inactivation (n=5) and 19.4 ± 7.9% with high-dose inactivations (n=4) (Fig. 6A1). Although, we observed larger deficit in success rate with the higher dose of muscimol inactivation, the differences were not statistically significant (F(2,27)=3.0, p=0.09).

Figure 6.

Motor cortex inactivation causes a dose-dependent loss of supination. Task performance during muscimol inactivations in (A) the pellet reaching task (None and Low: n = 5, High: n = 4) and (B) the knob task (n = 6). (A1) Success rate did not show significant changes with muscimol inactivation with the low or the high dose of muscimol. (A2) Quality of movement scores of supination significantly decreased with high dose of muscimol, but (A3) the scores for the other reaching movements showed no changes following inactivation. (B1) Success rate decreased significantly during the knob task in dose-dependent manner following low dose and high dose motor cortex inactivations. (B2) Supination angle also decreased significantly in dose-dependent manner. (B3). Peak velocity was significantly reduced after high dose inactivation. Three animals were crossover animals between the two tasks (symbols left/right facing triangles and circle). ** p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA comparing pre- and post-inactivation at Low and High dose.

We analyzed the quality of movement scores of the reaching movements for supination and ‘other’ movements separately, as described above. Supination (i.e. supination I and II movements) was diminished with inactivation (Fig. 6A2, F(2,11)=6.4, p=0.01). The differences between the pre-injury and high-dose inactivation scores were significant (p<0.05). In contrast, the quality of movement scores for the ‘other’ forelimb movements during pellet reaching did not change with the low-dose or the high-dose inactivations (Fig. 6A3, F(2,11)=1.8, p=0.2). The detailed analyses of all the forelimb reaching movements during inactivation are shown in supplemental Fig. S3. Thus, the pellet retrieval efficiency and the quality of movement for pellet reaching were not highly sensitive to CST inactivation.

Motor cortex inactivation in the Knob Supination Task

In contrast to pellet reaching, pharmacologic inactivation (n=6) significantly reduced the success rate of knob supination compared to baseline (Fig. 6B1, F(2,15)=22.3, p<0.001). The success rate in this task was on average 83.8 ± 1.4% before inactivation and it declined to 40.9 ± 13% with low-dose inactivation and 9.8 ± 3.7% with high-dose inactivation. Subsequent post-hoc analyses indicated significant differences from baseline success rate with both the low-dose (p=0.005) and the high-dose (p<0.001). Three animals were crossover animals between the knob and pellet task in this experiment (symbols right-facing triangle, left-facing triangle, and circle). The decrease in success rate for each of these animals after the low and high-dose inactivations showed similar trends with the rest of the group.

Pharmacologic inactivation also induced dose-dependent changes in the turn angle and velocity during the knob task. Before inactivation, rats supinated an average of 78.2 ± 1.2°. The turn angle decreased to 54.9 ± 8.2° and 32.1 ± 4.8° following low-dose and high-dose inactivations respectively (Fig. 6B2, F(2,15)=17.9, p<0.001). Finally, the velocity of knob supination was also significantly diminished by muscimol inactivation. The velocity differed significantly between the baseline and the post-inactivation testing (Fig. 6B3, F(2,15)=4.3, p<0.05). Thus, the knob supination task demonstrated impairment of the forelimb supination proportionate to the dose of the pharmacologic inactivation of motor cortex.

Discussion

The knob supination task proved sensitive to pyramidal tract injury and motor cortex inactivation in rats. The results mimic 4 features of human CST injury: 1) large-scale loss of function soon after injury30,31 2) gradual recovery of function in the weeks after injury32 3) persistent hand function impairment after endogenous recovery33 and 4) loss of function in proportion to the degree of CST damage34.

CST injury causes distal impairments, with the hand more affected than the upper arm16,35. Indeed, the pellet reaching movements most perturbed by injury to pyramidal tract injury (supplemental Fig. S2) or inactivation (supplemental Fig. S3) were pronation, supination, and grasp; proximal movements were hardly affected. The knob supination task involves each of these 3 most impaired movements. The rat must pronate before grasping the knob, otherwise there is not enough range of motion to supinate. Rats often fail to turn well after injury (supplemental video 2) or inactivation (supplemental videos 3 and 4) because they do not fully pronate first and grab the knob with digits on the side (partly supinated) rather than the top (fully pronated). The rats also perform a precision grip of the knob, which appeared challenging after injury and inactivation (supplemental videos 2, 3, and 4). Of course, the rats then have to supinate against a counter torque. For this aspect, the knob supination task showed alterations both in success rate and turn kinetics (Fig. 5).

Most people regain significant function after corticospinal injury, but rodent models often do not capture this recovery. This is perhaps because some rodent tasks are less reliant on CST and hence show minimal impairment post-injury16 while in other cases, it may be that they remain impaired following injury27. For example, the amount of recovery in stroke patients with usual care outstrips the effects of any current therapy36. Understanding injury-induced plasticity and how this process enables functional recovery is a key, but we have previously failed to show spontaneous recovery in rats29,37. A key advantage of recording the data from each trial performed on the knob is the ability to chart change over the course of a long experiment. This allows capture both of spontaneous recovery and recovery due to neural repair or rehabilitation.

For rodents to serve as models of repair, there must be an impairment to fix in the chronic stage of injury. Even though rats recover some supination during the 6 weeks after pyramidotomy, we observed a large residual deficit. This large delta provides the opportunity for CST repair strategies to translate into behavioral recovery. Importantly, the test cannot only answer whether function was recovered, but also whether the function is performed the same as before injury. Indeed, knob turn kinetics help distinguish a partially recovered animal from a fully recovered one (Fig. 5). Likewise, the test clearly distinguishes performance after low- and high-dose motor cortex inactivation (Fig. 6).

Currently available rodent studies are less focused on deficits of supination. Tests such as the horizontal ladder walking task or the rearing test not only are less suitably designed to study supination but they also measure metrics that aren’t relevant to CST function, such as paw placements on the rungs or paw preference29,38. And tasks such as the rotarod test, which is widely used in rodents, quantify behavior such as motor coordination and balance39,40. However, these behaviors are less reliant on the CST.

The design of the knob task offers several features that address the drawbacks in current rodent tasks. First, the task is automated, both in training and in analysis. In other tests, differences in how people train or test the rats is an important source of variability41. The adaptive algorithm we have implemented removes the subjective decision about how to advance task difficulty and rewards rats immediately, thereby motivating task learning. Automating the task enabled the training and testing of multiple animals simultaneously. In addition, it’s been shown that automating the task allows objective and efficient data analysis42 compared to current video based behavioral analysis. Finally, although the knob supination task was created as a measure of CST function, it can also be used to train supination. This could be very helpful in motor rehabilitation, given that task-specific motor skill training itself is known to improve skill reaching in rodents with stroke43. Rats consistently perform hundreds of trials a day, matching the intensity of studies that demonstrated training-induced functional recovery44.

Even though the knob task incorporates several features beneficial for understanding CST function, there are a few limitations in our approach. Firstly, by constraining forelimb movement to supination, we limit the ability to detect other forelimb movements important for arm and hand function. In addition, while we have established that the task is sensitive to pyramidotomy, we have not tested whether supination is a specific function of the CST. Given that pyramidotomy damages both direct CST connections and cortico-reticulospinal connections, functional loss may be due to both direct and indirect pathways. Also, although supination is an important part of forelimb function in the rats in the laboratory and in wild, reaching to grasp and turn is not a natural movement for them. Perhaps because it is not a natural movement, our supination task requires highly intensive training in order for rats to acquire proficiency. Further, the behavioral improvement observed after pyramidotomy was likely a combination of spontaneous and training-induced recovery. We do not observe any differences between rats that performed each of the two behavioral tasks individually and those that performed both tasks. However, the numbers of animals in each group was limited, and there is a possibility of interaction between the training effects of each task. We are addressing the long training time not just by automating the task, but also by experimenting with home cage habituation and a less restrictive baseline criterion.

Finally, we hypothesize that testing functions important to people with neurological impairments in rats will help translate promising therapies from the lab to the clinic. To further facilitate translation, devices to test supination in people are becoming available45,46 allowing the same outcome measure for both preclinical and clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Brendan Flynn’s contributions in early stages of the knob device development and behavior testing.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant number NS091737 (JBC). Development of the task as also supported by a National Institutes of Health SBIR grant NS086344 (AMS, RLR).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: JBC received a one-time consulting fee from Vulintus, Inc., which is developing behavioral tests used in this research under NINDS SBIR grant R44NS086344. JBC owns no shares and has no financial interest in Vulintus, Inc. AMS and RLR own shares in, and AMS is now primarily employed by, Vulintus, Inc. AMS and RLR participated in the device design, but did not contribute to data collection, analysis or the decision to publish.

References

- 1.Lawrence DG, Kuypers HG. The functional organization of the motor system in the monkey. II. The effects of lesions of the descending brain-stem pathways. Brain. 1968;91(1):15–36. doi: 10.1093/brain/91.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemon RN. Descending pathways in motor control. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:195–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng WW, Wang J, Chhatbar PY, et al. Corticospinal Tract Lesion Load: An Imaging Biomarker for Stroke Motor Outcomes. Annals of neurology. 2015;78(6):860–870. doi: 10.1002/ana.24510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friel KM, Kuo HC, Carmel JB, Rowny SB, Gordon AM. Improvements in hand function after intensive bimanual training are not associated with corticospinal tract dysgenesis in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Experimental brain research. 2014;232(6):2001–2009. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-3889-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin JH. Systems neurobiology of restorative neurology and future directions for repair of the damaged motor systems. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2012;114(5):515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alstermark B, Pettersson LG. Skilled reaching and grasping in the rat: lacking effect of corticospinal lesion. Fronteirs in neurology. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alstermark B, Ogawa J, Isa T. Lack of monosynaptic corticomotoneuronal EPSPs in rats: disynaptic EPSPs mediated via reticulospinal neurons and polysynaptic EPSPs via segmental interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91(4):1832–1839. doi: 10.1152/jn.00820.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell WW, DeJong RN. DeJong’s the neurologic examination/William W. Campbell. 7th. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braendvik SM, Elvrum AK, Vereijken B, Roeleveld K. Relationship between neuromuscular body functions and upper extremity activity in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(2):e29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klotz MC, Kost L, Braatz F, et al. Motion capture of the upper extremity during activities of daily living in patients with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Gait & posture. 2013;38(1):148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackey AH, Walt SE, Stott NS. Deficits in upper-limb task performance in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy as defined by 3-dimensional kinematics. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2006;87(2):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teitelbaum JS, Eliasziw M, Garner M. Tests of motor function in patients suspected of having mild unilateral cerebral lesions. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002;29(4):337–344. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100002201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmel JB, Berrol LJ, Brus-Ramer M, Martin JH. Chronic electrical stimulation of the intact corticospinal system after unilateral injury restores skilled locomotor control and promotes spinal axon outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2010;30(32):10918–10926. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1435-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmel JB, Kim S, Brus-Ramer M, Martin JH. Feed-forward control of preshaping in the rat is mediated by the corticospinal tract. The European journal of neuroscience. 2010;32(10):1678–1685. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raineteau O, Fouad K, Noth P, Thallmair M, Schwab ME. Functional switch between motor tracts in the presence of the mAb IN-1 in the adult rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(12):6929–6934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111165498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whishaw IQ, Piecharka DM, Drever FR. Complete and partial lesions of the pyramidal tract in the rat affect qualitative measures of skilled movements: impairment in fixations as a model for clumsy behavior. Neural plasticity. 2003;10(1–2):77–92. doi: 10.1155/NP.2003.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whishaw IQ. Loss of the innate cortical engram for action patterns used in skilled reaching and the development of behavioral compensation following motor cortex lesions in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39(5):788–805. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLellan CL, Gyawali S, Colbourne F. Skilled reaching impairments follow intrastriatal hemorrhagic stroke in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175(1):82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurd C, Weishaupt N, Fouad K. Anatomical correlates of recovery in single pellet reaching in spinal cord injured rats. Exp Neurol. 2013;247:605–614. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simpson J, Kelly JP. An investigation of whether there are sex differences in certain behavioural and neurochemical parameters in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 2012;229(1):289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alaverdashvili M, Whishaw IQ. A behavioral method for identifying recovery and compensation: hand use in a preclinical stroke model using the single pellet reaching task. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(5):950–967. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whishaw IQ, Gorny B, Sarna J. Paw and limb use in skilled and spontaneous reaching after pyramidal tract, red nucleus and combined lesions in the rat: behavioral and anatomical dissociations. Behav Brain Res. 1998;93(1–2):167–183. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whishaw IQ, Pellis SM, Gorny BP, Pellis VC. The impairments in reaching and the movements of compensation in rats with motor cortex lesions: an endpoint, videorecording, and movement notation analysis. Behav Brain Res. 1991;42(1):77–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khodaparast N, Hays SA, Sloan AM, et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Delivered During Motor Rehabilitation Improves Recovery in a Rat Model of Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1545968314521006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna JE, Whishaw IQ. Complete compensation in skilled reaching success with associated impairments in limb synergies, after dorsal column lesion in the rat. J Neurosci. 1999;19(5):1885–1894. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01885.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brus-Ramer M, Carmel JB, Chakrabarty S, Martin JH. Electrical stimulation of spared corticospinal axons augments connections with ipsilateral spinal motor circuits after injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27(50):13793–13801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3489-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brus-Ramer M, Carmel JB, Martin JH. Motor cortex bilateral motor representation depends on subcortical and interhemispheric interactions. J Neurosci. 2009;29(19):6196–6206. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5852-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmel JB, Kimura H, Berrol LJ, Martin JH. Motor cortex electrical stimulation promotes axon outgrowth to brain stem and spinal targets that control the forelimb impaired by unilateral corticospinal injury. The European journal of neuroscience. 2013;37(7):1090–1102. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carmel JB, Kimura H, Martin JH. Electrical stimulation of motor cortex in the uninjured hemisphere after chronic unilateral injury promotes recovery of skilled locomotion through ipsilateral control. J Neurosci. 2014;34(2):462–466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3315-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duncan PW, Goldstein LB, Horner RD, Landsman PB, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Similar motor recovery of upper and lower extremities after stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1994;25(6):1181–1188. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.6.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feys H, De Weerdt W, Nuyens G, van de Winckel A, Selz B, Kiekens C. Predicting motor recovery of the upper limb after stroke rehabilitation: value of a clinical examination. Physiotherapy research international: the journal for researchers and clinicians in physical therapy. 2000;5(1):1–18. doi: 10.1002/pri.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwakkel G, Kollen B, Lindeman E. Understanding the pattern of functional recovery after stroke: Facts and theories. Restor Neurol Neuros. 2004;22(3–5):281–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwakkel G, Kollen B, Twisk J. Impact of time on improvement of outcome after stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2006;37(9):2348–2353. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000238594.91938.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng W, Wang J, Chhatbar PY, et al. Corticospinal tract lesion load: An imaging biomarker for stroke motor outcomes. Annals of neurology. 2015;78(6):860–870. doi: 10.1002/ana.24510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shelton FN, Reding MJ. Effect of lesion location on upper limb motor recovery after stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2001;32(1):107–112. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf SL, Winstein CJ, Miller JP, et al. Effect of constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity function 3 to 9 months after stroke: the EXCITE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;296(17):2095–2104. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qin L, Jing D, Parauda S, et al. An adaptive role for BDNF Val66Met polymorphism in motor recovery in chronic stroke. J Neurosci. 2014;34(7):2493–2502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4140-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Starkey ML, Barritt AW, Yip PK, et al. Assessing behavioural function following a pyramidotomy lesion of the corticospinal tract in adult mice. Experimental Neurology. 2005;195(2):524–539. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carter RJ, Morton J, Dunnett SB. Motor coordination and balance in rodents. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0812s15. Chapter 8: Unit 8 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding Y, Li J, Lai Q, et al. Motor balance and coordination functional outcome in rat with cerebral artery occlusion training enhances transient middle. Neuroscience. 2004;123(3):667–674. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caro TM, Roper R, Young M, Dank GR. Inter-Observer Reliability. Behaviour. 1979;69:303–315. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sloan AM, Fink MK, Rodriguez AJ, et al. A Within-Animal Comparison of Skilled Forelimb Assessments in Rats. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maldonado MA, Allred RP, Felthauser EL, Jones TA. Motor skill training, but not voluntary exercise, improves skilled reaching after unilateral ischemic lesions of the sensorimotor cortex in rats. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22(3):250–261. doi: 10.1177/1545968307308551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacLellan CL, Keough MB, Granter-Button S, Chernenko GA, Butt S, Corbett D. A critical threshold of rehabilitation involving brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for poststroke recovery. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25(8):740–748. doi: 10.1177/1545968311407517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lambercy O, Dovat L, Gassert R, Burdet E, Teo CL, Milner T. A haptic knob for rehabilitation of hand function. IEEE transactions on neural systems and rehabilitation engineering: a publication of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2007;15(3):356–366. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2007.903913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin S, Park E, Lee DH, Lee KJ, Heo JH, Nam HS. An objective pronator drift test application (iPronator) using handheld device. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.