Abstract

Activated sludge is an artificial ecosystem known to harbor complex microbial communities. Bacterial diversity in activated sludge from pulp and paper industry was studied to bioprospect for laccase, the multicopper oxidase applicable in a large number of industries due to its ability to utilize a wide range of substrates. Bacterial diversity using 454 pyrosequencing and laccase diversity using degenerate primers specific to conserved copper binding domain of laccase like multicopper oxidase (LMCO) genes were investigated. 1231 OTUs out of 11,425 sequence reads for bacterial diversity and 11 OTUs out of 15 reads for LMCO diversity were formed. Phylum Proteobacteria (64.95 %) with genus Thauera (13.65 %) was most abundant followed by phylum Bacteriodetes (11.46 %) that included the dominant genera Paludibacter (1.93 %) and Lacibacter (1.32 %). In case of LMCOs, 40 % sequences showed affiliation with Proteobacteria and 46.6 % with unculturable bacteria, indicating considerable novelty, and 13.3 % with Bacteroidetes. LMCOs belonged to H and J families.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12088-016-0624-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Bacteria, LMCO, Diversity, Activated sludge, Paper industry

Introduction

Industrial demand for novel biocatalysts is on the rise due to strict Government legislations on the usage of hazardous chemicals. Diversity analysis of complex ecosystems provides the opportunity to identify novel rare enzymes. Bacteria form the major population of any ecosystem due to their metabolic versatility arising from the ability to transfer genes. Structures of several bacterial communities using culture dependent and independent methods have been studied in order to identify the major players responsible for biodegradation of organic compounds and transformation of toxic compounds into harmless products [1]. Moreover, genes of enzymes having industrial potential were cloned directly from metagenome of activated sludge [2, 3]. Microbial populations of activated sludge were investigated by various researchers using PCR-based 454 pyrosequencing [4, 5]. However, activated sludge of pulp and paper industry has not been explored so far. Microbial community and novel features of enzymes depend on the physical and chemical characteristics of the sludge which further depend on the type of industry [6]. In pulp and paper industry, lignin, lignin derivatives or chloro-lignin derivatives are the major released compounds. The lignin polymer is highly resistant towards chemical and biological degradation due to its structure. Recently, Christopher et al. [7] reviewed the biodegradation of lignin with laccase mediator system and observed that no ideal laccase has been reported till now for its degradation. Laccase is a multicopper enzyme found in a wide range of taxa including plants, fungi, bacteria, insects and bacteria. Recently, laccase was also reported in yeast [8]. It performs reactions in ecofriendly manner, requires only oxygen to catalyze the oxidation of phenolic compounds and produces water as by product. The majority of known laccases are from fungi. However, bacterial laccases show higher stability at variable pH and temperature and are easier to produce [9]. Diamantidis et al. [10] identified the first bacterial laccase in Azospirillum lipoferum. Formation of spore coat protein in Bacillus [11], morphogenesis in Streptomyces [12], protection of nitrogenase from oxygen in Azotobacter and detoxification of phenolic compounds in nodules and roots are some known functions of laccases in bacteria [13]. Bacterial laccases generally require high cost mediators, due to their low redox potential, which hampers their use at industrial level. Another drawback of bacterial laccases is their low production. Attempts were made to immobilize the laccase in order to enhance stability [14]. However, conformational changes and a slight loss of activity during immobilization processes are some hurdles for their application in the industry [15]. Identifying potential sources can play a role in isolation of novel bacterial laccases that have the ability to stand industrial conditions. In this work, activated sludge from paper industry was explored for bacterial and laccase diversity based on the premise that microbes living in harsh conditions like high concentration of chemicals and varied pH may have evolved unique novel features in their enzymes for their survival.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

Activated sludge was obtained from Ballarpur pulp and paper industry, Yamuna Nagar, India (average pH-7.8). DNA from sludge samples was extracted [16] and purified [17].

Phenol Oxidase Activity in Sludge

Laccase activity in activated sludge was measured as described by Floch et al. [18]. 1 g of activated sludge was mixed with 9 ml of normal saline and was shaken for 1 h with glass beads on a horizontal shaker. This suspension was centrifuged and supernatant was used for assaying the activity using 2 mM ABTS at different pH (5, 6, 7, 8) and temperatures 37–75 °C. Controls were set up using autoclaved sludge suspension.

Amplification and Next Generation Sequencing of 16S rRNA Amplicon

PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes was done by a primer set specific to bacteria: 8F (GAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG) and 1492R (GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT). Amplification was carried out in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 1X Taq buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 U Taq DNA Polymerase (Fermentas), 200 μM dNTP’s, 0.1 μM of each primer, 50 ng extracted DNA, using the conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 10 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 58 °C for 1 min and extension at 72 °C for 1 min 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min that was followed by cooling to 4 °C.

Purified DNA was further used to amplify the variable region of the 16S rRNA gene (V1-3) using 8F and 519R (GTNTTACNGCGGCKGCTG) primers. These primers contained the appropriate adaptor (454 Adapter 1-CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTCCGAC; 454 Adapter 2-CCTATCCCCTGTGTGCCTTGGCAGTC) and barcode sequences that were necessary for running the samples on the GS-FLX-Titanium (Roche) sequencer. PCR reaction was done as described above. The entire PCR amplicon was loaded onto a 1 % agarose gel and the correct size band (500–600 bp) was excised from the gel and purified. The DNA concentrations were quantified using Nanodrop spectrophotometer. DNA was pyrosequenced using the GS-FLX-Titanium series (Roche) by Chun Lab, South Korea. The raw sequence reads were deposited in the NCBI sequencing read archive under Accession No. SRR1997905.

Assessment of Bacterial Community

Chimeric sequences were removed using UCHIME program after trimming the barcode, linker, and PCR primer sequences [19]. Further, sequence reads were assembled and taxonomic assignment of each read was conducted using the EzTaxon-e database, which contains representative phylotypes of cultured and uncultured sequences in the GenBank database [20]. The operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were defined with the CD-HIT program [21]. The richness and diversity of samples were calculated according to the Chao1 estimation and Shannon index at the 3 % dissimilarity level using the Mothur program [22].

Amplification, Cloning and Sequencing of LMCO Genes

The PCR reaction was performed on the extracted DNA samples using degenerate primers Cu1AF (ACMWCBGTYCAYTGGCAYGG) and Cu2R (GRCTGTGGTACCAGAANGTNCC) [23] for the amplification of conserved LMCO gene region. Each PCR reaction contained 1X Taq buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 1.5 U Taq Polymerase (Fermentas), 200 μM dNTP’s, 1.2 μM of each primer, 50 ng extracted DNA and nuclease free water in the final reaction volume of 20 μl. The PCR amplification program was initiated at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 32 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 49.5 °C for 1 min and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min that was then followed by cooling to 4 °C. Purified DNA was ligated to T-Vector (INSTANT CLONING KIT, GeNei) according to protocol provided by manufacturer. Electrocompetent cells of Escherichia coli DH10β were prepared [24] and electroporated with ligated DNA using optimal settings (1.0 mm cuvette 10 µF capacitor and 1800 Volts). Screening of positive clones was done on the basis of blue white colonies [25] and colony PCR [26].

Analysis of LMCO Sequences

Nucleotide sequences were deposited in the GeneBank under the accession numbers KT187938 to KT187952 and were compared with the NCBI database the BLAST search algorithm. Sequences were aligned using clustalW, implemented in MEGA5 software which was also used for neighbor joining tree construction using nucleic acid sequences. OTUs were established at 3 % genetic distance. The OTU based analysis (Shannon and Simpson diversity indices) was performed using Mothur software [22].

Results and Discussion

Phenol Oxidase Activity

The culturable bacterial diversity isolated by using M162 medium [27] containing guaiacol (2 mM) and CuSO4 (100 uM) at different temperatures did not show any laccase activity. However, phenol oxidase activity (43 nkat/g) was observed in sludge suspension maximally at 60 °C and pH 6.5.

Bacterial Diversity

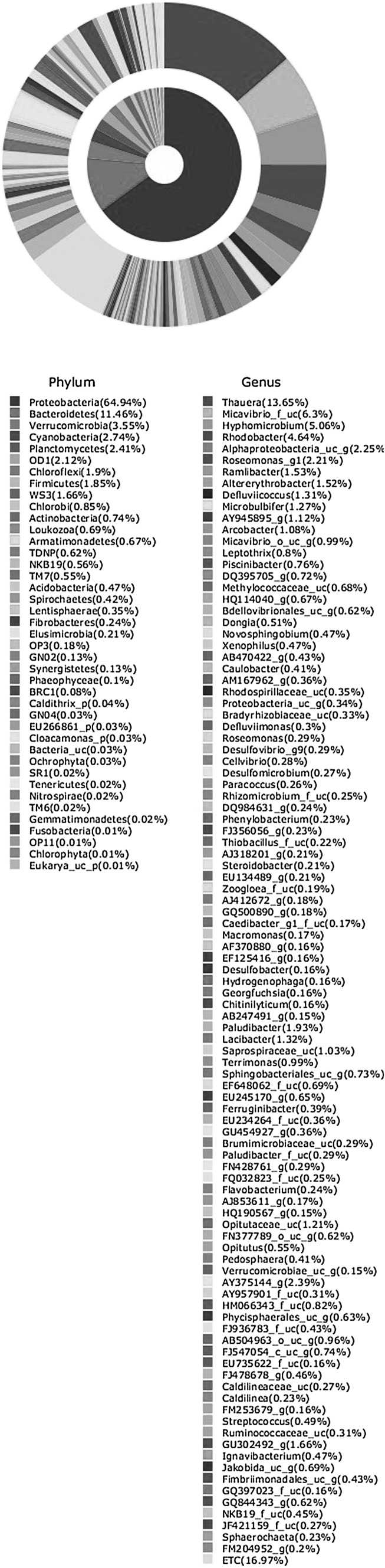

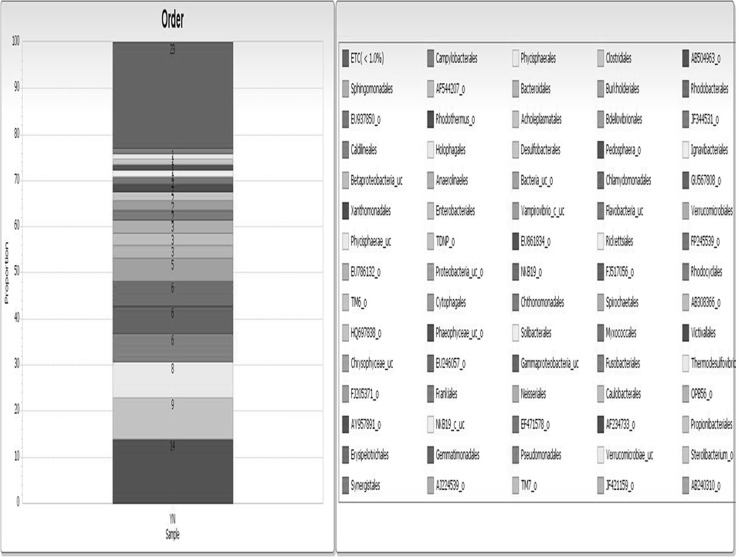

A total of 11,425 16SrRNA sequence reads generated 1231 OTUs. Diversity indices viz. Shannon-Wiener index (5.53) and Simpson index (0.012) were calculated at a genetic distance of 3 % which represented high diversity and low evenness as Simpson index approached zero. Further, these sequences were classified from phylum to genus level using EzTaxon-e database (http://www.ezbiocloud.net/eztaxon). The bacterial phylotypes detected are shown in Fig. 1. Phylum Proteobacteria (64.95 %) with genus Thauera (13.65 %) followed by phylum Bacteriodetes (11.46 %) including genera Paludibacter (1.93 %) and Lacibacter (1.32 %) were dominant. Other dominant phyla were Verrucomicrobia (3.55 %), Plactomycetes (2.41 %), Firmicutes (1.85 %) and Chloroflexi (1.9 %). Cyanobacteria also formed a dominant phylum which was not identified in previous studies (Table S1) though Kirkwood et al. [28] suggested their occurrence in paper and pulp mill wastes. Other phyla which constituted more than one percent were WS3 and OD1. Those less than one percent were Actinobacteria and Acidobacteria, TM7, Thermotogae, Spirochaetes, Nitrospira and Synergistetes. Fibrobacteres, Chrysiogenetes, Tenericutes, Elusimicrobia, Chlamydiae, Lentisphaerae and Chlorobi were the other phyla (<0.05 %). Order Zoogloea_o (14 %) was the most abundant followed by Micavibrio (9 %) and Rhizobiales (8 %) belonging to the phylum Proteobacteria. Orders Sphingobacteriales (6 %) and Bacteroidales (3 %) formed major part of the sequences belonging to Bacteroidetes. AF544207 from Cyanobacteria, AB530233 from WS3 and AB504963 from OD1 were other major orders in the community. Orders representing less than 1 % of sequences or phylotypes formed 23 % of the total microbial community (Fig. 2). Thauera was the most abundant genus belonging to subdivision β-proteobacteria followed by Micavibrio, Hyphomicrobium, Rhodobacter and Roseomonas from subdivision α-proteobacteria.

Fig. 1.

Pie chart representing the composition of microbial community (phyla and genera)

Fig. 2.

Microbial orders representing the taxonomic composition of microbial community

Proteobacteria was the most abundant phylum followed by Bacteroidetes similar to the activated sludge of 14 sewage plants studied by Zhang et al. [5]. Subdivisions α and β-proteobacteria were in equal proportions. Diverse genera of α-proteobacteria were present, in comparison to β-proteobacteria, dominated by genus Thauera, known for its capability to degrade hydrocarbons and phenols which is congruous with the presence of carbohydrates and phenolic compounds in the effluent of paper industry. Other dominant genera were Micavibrio, a microbial predator of Gram negative bacteria and Hyphomicrobium, a Gram-negative budding bacterium. Some species of Hyphomicrobium carry out denitrification and use methanol as the carbon source. Rhodobacter was another dominant genus, known to degrade chlorophenols, the major compounds released by paper industry. Paludibacter and Lacibacter genera from Bacteroidetes have been isolated from the ecosystems which are rich in organic matter like rice field and eutrophic lake. Some sequences showed similarity with uncultured bacteria (AF544207, AB530233 and GU302492) derived from rumen, bay and microbial mat which are rich in organic carbon similar to activated sludge of pulp and paper industry due to usage of plant biomass for paper manufacturing. Other sequences similar to Chitinilyticum and Cellvibrio were also observed. In this study, some common genera were found which were earlier reported in activated sludge but there is variation in dominance of the genera (Table S1). This may be because activated sludge samples studied were from different industries, geographical locations and due to the variation in technique used in previous studies.

Laccase Diversity

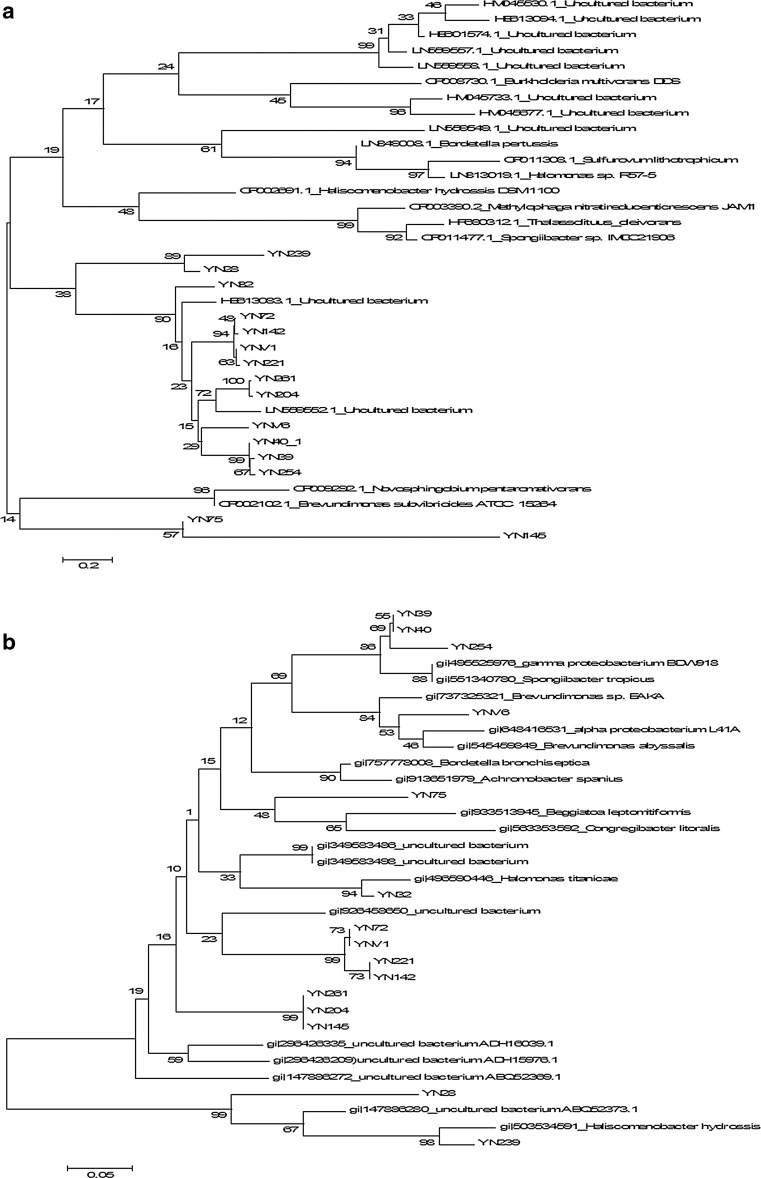

A total of 37 sequences were obtained. LMCO nucleotide sequences which were completely identical were taken as one sequence and 11 OTUs were formed out of 15 sequences based on 97 % identity cutoff. Diversity indices viz. Shannon-Wiener index (1.93) and Simpson index (0.047) at a genetic distance of 3 % indicated moderate level of diversity and low evenness. The LMCO (nucleotide and amino acid) sequences were aligned with those retrieved from Gene Bank followed by phylogenetic tree construction (Fig. 3a, b). Majority of the obtained LMCO nucleotide sequences clustered only with four reference sequences. This large clade further split into two major subclades. One subclade contained YN145 and YN75 and LMCO from Novosphingobium and Brevundimonas, belonging to class alpha proteobacteria. YN 145 and YN75 showed identity with LMCO gene from uncultured bacteria by BLASTn (Fig. 3a). In BLASTx search, YN75 showed similarity with LMCO protein from Porticoccus hydrocarbonoclasticus (77 %) and YN145 with LMCO from uncultured ABQ52369 (81 %). The second subclade contained all the LMCO sequences that clustered with unculturable bacterial LMCOs. This topology of the tree hampered the classification of YN LMCOs. However, LMCO protein sequences clustered with reference LMCO sequences retrieved from NCBI. Four distinct proteobacterial clusters were identified (Fig. 3b), each with reference sequences from different genera of Proteobacteria. The phylogenetic tree also contained one Bacteroidetes-associated cluster with different branch lengths, indicating that these sequences were notably different from their neighboring groups. The phylogenetic association of the seven sequences in the tree was not clear as they clustered with LMCO proteins from unculturable bacteria.

Fig. 3.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree based on comparison of laccase encoding gene fragment (a) and the corresponding amino acid sequences (b) with their closest phylogenetic relatives. Phylogenetic tree was constructed based on aligned datasets using Neighbour joining (NJ) method and the program MEGA 5. Numbers on the tree indicate percentage of bootstrap sampling derived from 1000 random samples

YN40 and YN254 showed similarity with LMCO from Spongibacter (88 and 86 % respectively), YN39 with LMCO from Thalassolituus oleivorans (84 %) in BLASTn search and clustered in one clade with LMCO protein from gammaproteobacterium BDW918. BLASTx search revealed similarity of YN40 and YN39 to gammaproteobacterium BDW918 (identity 96 and 93 % respectively) and YN254 to Haliea salexigens (89 %). YN32 displayed its identity with LMCO from Halomonas in BLASTn (97 %) as well as in BLASTx (96 %) searches. YN72 and YNV1 showed identity (79 %) with LMCO from uncultured bacteria with accession number HM045530, YN221 with HE601574 (79 %) and YN142 with LN559521 (86 %) in BLASTn search. BLASTx search indicated that all the sequences matched with LMCO protein from Bordetella bronchiseptica albeit with different levels of similarity. YN261 and YN204 clustered and matched with LMCO genes of uncultured bacteria from compost with accession numbers LN559552 (78 %) and LN559558 (80 %) in BLASTn search. However, BLASTx search showed that both had identity with a putative LMCO with accession number ADH16039 (YN 261 with 83 % identity; YN204 with 85 % identity). In bacterial diversity, a number of unculturable alpha and beta-proteobacteria were found not classified at genus level which depicts the possibility of LMCO genes from these unculturable Proteobactria.

In BLASTn search YNV6 showed similarity with LMCO from Novosphingobium pentaromativorans (84 %), but BLASTx search showed that YNV6 belonged to alpha proteobacterium U9ili (93 %). However, in phylogenetic tree YNV6 clustered with Brevundimonas from order Caulobacterales. 16S rRNA sequences for Caulobacterales were found in bacterial diversity but not for Brevundimonas which suggests that this LMCO protein may belong to unculturable genus of this order. YN239 showed identity with LMCO sequence of Heliscomenobacter hydrossis (BLASTn = 87 %; BLASTx = 93 %) and YN28 showed highest identity (77 %) with uncultured bacterial LMCO gene (HM045733). Blastx search indicated its similarity (76 %) with uncultured bacterial LMCO ADH16094. YN239 and YN28 clustered with Haliscomenobacter, a bacteroidetes from family Saprospiraceae. Presence of 16S rRNA sequences of unculturable Saprospiraceae in bacterial diversity of this sample showed association of these LMCOs with this family of bacteria.

LMCO nucleotide sequences from this study did not cluster with previously studied ones from forest [23] and peat soil [29]. However, sequences clustered with LMCO sequences (LN559552 and HE613083) retrieved from agricultural compost that shows similarity with activated sludge of pulp and paper industry in the type of organic matter or partially degraded organic matter which proposed that LMCOs with same functions may have similar sequences. However, some sequences showed significant dissimilarity with those from agricultural compost inferring them as different due to the fact that LMCOs in activated sludge are actively involved in degradation of pollutants in contrast to compost which does not contain pollutants like chloro-ligno-derivatives. LMCO sequences were also BLASTed against LaccED database and it was observed that all sequences belonged to H family except two (YN239 and YN28) belonging to J family (bacterial CueO) which did not cluster with any other sequence in phylogenetic tree.

Current knowledge about distribution of laccases is scant which causes difficulty in their isolation and production and requirement of expensive mediators further impedes their successful implementation at the industrial scale. Activated sludge of pulp and paper industry was explored for the first time for bacterial and LMCO diversity by using metagenomic approach. Exploration of this ecosystem can provide novel LMCOs due to the fact that bacteria and bacterial enzymes acquire adaptations so as to evolve. Previously, in our laboratory [30] a novel LMCO was isolated that could deink the recycled waste paper without the need of any mediator. Bacterium producing this LMCO was isolated from industrial effluent which confirms that LMCOs from this type of sources may have novel properties. Thus the approach might give clues to the involvement of LMCOs playing role in degradation of pollutants, lignin or lignin derivatives and their application in industry. Our ongoing attempts to clone these laccases may find novel enzymes for industrial application.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

References

- 1.Sharma N, Tanksale H, Kapley A, Purohit HJ. Mining the metagenome of activated biomass of an industrial wastewater treatment plant by a novel method. Indian J Microbiol. 2012;52:538–543. doi: 10.1007/s12088-012-0263-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapardar RK, Ranjan R, Puri M, Sharma R. Sequence analysis of a salt tolerant metagenomic clone. Indian J Microbiol. 2010;50:212–215. doi: 10.1007/s12088-010-0041-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang T, Han WJ. Gene cloning and characterization of a novel esterase from activated sludge metagenome. Microb Cell Fact. 2009;67:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-8-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rani A, Porwal S, Sharma R, Kapley A, Purohit HJ, Kalia VC. Assessment of microbial diversity in effluent treatment plants by culture dependent and culture independent approaches. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:7098–8107. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang T, Shao MF, Ye L. 454 Pyrosequencing reveals bacterial diversity of activated sludge from 14 sewage treatment plants. ISME J. 2012;6:1137–1147. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbride KA, Frigon D, Cesnik A, Gawat J, Fulthorpe RR. Effect of chemical and physical parameters on a pulp mill biotreatment bacterial community. Water Res. 2006;40:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christopher LP, Yao B, Ji Y. Lignin biodegradation with laccase-mediator systems. Energy Res. 2014;2:1–13. doi: 10.12989/eri.2014.2.1.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalyani D, Tiwari MK, Li J, Kim SC, Kalia VC, Kang YC, et al. A highly efficient recombinant laccase from the Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica and its application in the hydrolysis of biomass. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel SKS, Kalia VC, Choi JH, Haw JR, Kim IW, Lee JK. Immobilization of laccase on SiO2 nanocarriers improves its stability and reusability. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;24:639–647. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1401.01025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamantidis G, Effosse A, Potier P, Bally R. Purifcation and characterization of the first bacterial laccase in the rhizospheric bacterium Azospirillum lipoferum. Soil Biol Biochem. 2000;32:919–927. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(99)00221-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hullo M-F, Moszer I, Danchin A, Martin-Verstraete I. CotA of Bacillus subtilis is a copper-dependent laccase. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5426–5430. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5426-5430.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endo K, Hosono K, Beppu T, Ueda K. A novel extracytoplasmic phenol oxidase of Streptomyces: its possible involvement in the onset of morphogenesis. Microbiology. 2002;148:1767–1776. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herter S, Schmidt M, Thompson ML, Mikolasch A, Schauer F. A new phenol oxidase produced during melanogenesis and encystment stage in the nitrogen-fixing soil bacterium Azotobacter chroococcum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;90:1037–1049. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel SKS, Choi SH, Kang YC, Lee J-K. Large-scale aerosol-assisted synthesis of biofriendly Fe2O3 yolk–shell particles: a promising support for enzyme immobilization. Nanoscale. 2016;8:6728–6738. doi: 10.1039/C6NR00346J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arroyo M. Inmobilized enzymes: theory, methods of study and applications. Ars Pharmaceutica. 1998;39:23–39. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Bruns MA, Tiedje JM. DNA recovery from soils of diverse. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:316–322. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.316-322.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma P, Capalash N, Kaur J. An improved method for single step purification of metagenomic DNA. Mol Biotechnol. 2007;36:61–63. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-0015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Floch C, Alarcon-Gutierrez E, Criquet S. ABTS assay of phenol oxidase activity in soil. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;71:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim OS, Cho YJ, Lee K, et al. Introducing EzTaxon-e: a prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene sequence database with phylotypes that represent uncultured species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:716–721. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.038075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, et al. Introducing mothur: opensource, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellner H, Luis P, Zimdars B. Diversity of bacterial laccase-like multicopper oxidase genes in forest and grassland Cambisol soil samples. Soil Biol Biochem. 2008;40:638–648. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller EM, Nickoloff JA. Escherichia coli electrotransformation. In: Nickoloff JA, editor. Electroporation protocols for microorganisms. Totowa: Humana Press; 1995. pp. 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langley KE, Villarejo MR, Fowler AV, Zamenhof PJ, Zabin I. Molecular basis of beta-galacosidase α-complentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:1254–1257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green MR, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degryse E, Glansdorff N, Pierard A. A comparative analysis of thermophilic bacteria belonging to the genus Thermus. Arch Microbiol. 1978;117:189–196. doi: 10.1007/BF00402307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirkwood AE, Nalewajko C, Fulthorpe RR. The occurrence of cyanobacteria in pulp and paper waste-treatment systems. Can J Microbiol. 2001;47:761–766. doi: 10.1139/w01-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ausec L, Dirk J, Elsas V, Mandic-mulec I. Two- and three-domain bacterial laccase-like genes are present in drained peat soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43:975–983. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Virk AP, Puri M, Gupta V, Capalash N, Sharma P. Combined enzymatic and physical deinking methodology for efficient eco-Friendly recycling of old newsprint. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paranthaman SR, Karthikeyan B. Studies on different indigenous microorganisms in pulp and paper industry effluent. Indian Streams Res J. 2013;3:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah PM. Exploited application of pyrosequencing in microbial diversity of activated sludge system of common effluent treatment plants. Am J Microbiol Res. 2014;2:157–165. doi: 10.12691/ajmr-2-5-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.