Abstract

S100B belongs to a family of calcium-binding proteins implicated in intracellular and extracellular regulatory activities. This study of serum S100B in primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) is based on data obtained from a randomized, controlled trial of Interferon β-1a in subjects with PPMS. The key questions were whether S100B levels were associated with either disability or MRI findings in primary progressive MS and whether Interferon β-1a has an effect on their S100B levels. Serial serum S100B levels were measured using an ELISA method. The results demonstrated that serum S100B is not related to either disease progression or MRI findings in subjects with primary progressive MS given Interferon β-1a. Furthermore there is no correlation between S100B levels and the primary and secondary outcome measures.

Keywords: serum S100B, primary progressive multiple sclerosis, Interferon β-1a, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

S100B belongs to a family of calcium-binding proteins implicated in intracellular and extracellular regulatory activities [2]. Intracellularly, it exhibits regulatory effects on cell growth, differentiation, cell shape and energy metabolism. Extracellularly, S100B stimulates neuronal survival, differentiation, astrocytic proliferation, neuronal death via apoptosis, and stimulates (in some cases) or inhibits (in others) activity of inflammatory cells.

Several studies suggest that S100B has a role in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS). Phenotypically and functionally similar T cells specific against S100B can be detected in the peripheral blood of MS patients making S100B a putative candidate auto-antigen in MS [15]. Furthermore, S100B may act as a cytokine [2,10,11] and in vitro studies show that, at high levels, S100 can induce the neuronal expression and secretion of pro-inflammatory interleukin-6. In addition, elevated levels of S100B have been detected in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of MS patients during acute phases or exacerbations of the disease [10] and it has therefore been proposed that elevated S100B may be indicative of active cell injury [11].

Interferon-β (IFN-β) is effective in reducing relapse rate in relapsing-remitting [6,14,17] and secondary progressive MS [3] but the mechanisms behind the beneficial action of IFNβ are not fully understood. Two potential sites of action are on cytokine production [1,4,12] and on the entry of leukocytes into the CNS [8,9,16,18].

In this clinically negative phase II study [7], we assessed the effect of IFNβ-1a on serum levels of S100B at 3-month intervals in subjects with primary progressive MS (PPMS). The key questions were whether serum S100B levels correlated with disability or MRI findings in patients with PPMS, and whether IFN-β has an effect on levels of serum S100B.

Methods

Patients and examination

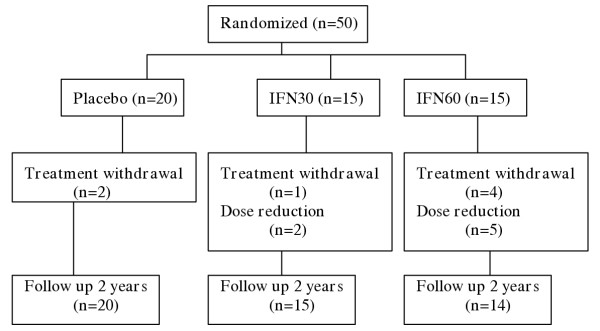

Fifty patients with PPMS were recruited in a phase II trial of IFNβ-1a (Avonex®, Biogen) and were assessed three monthly over a study period of 2 years. Fifteen of these patients were treated with IFNβ-1a 30μg intramuscularly (im) weekly (IFN30), 15 received IFNβ-1a 60μg im weekly (IFN60) and 20 with placebo. IFNβ-1a was reduced to half dose in 5 subjects receiving 60μg im weekly, and in 2 subjects receiving IFNβ-1a 30μg im weekly. Seven subjects withdrew from treatment [7] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fifty subjects with PPMS were randomised in a phase II trial of Interferon β-1a and were assessed 3 monthly over a 2-year study period. n = number of subjects with PPMS

Neurological examination was performed at each visit and disability was measured using Kurtzke's expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Progression was defined as a sustained (3 months apart) increase of at least 1.0 on the EDSS scale between 0 to 5 and 0.5 for subjects with EDSS score of 5.5 and above.

Fourteen healthy subjects served as controls.

All subjects provided informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. This study was approved by the ethics committee and has therefore been performed with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

MR imaging and analyses

MRI was performed at baseline and 6 monthly for 2 years. Only baseline and year 2 data were included in this study. Brain and spinal cord atrophy, ventricular volume, T1 and T2 lesion load were measured as described elsewhere [7].

Serum S100B levels

Serum samples were centrifuged and stored at -20°C. Serum S100B levels were quantified using a modified ELISA method as previously described by Green et al. [5]. Ninety-six-well plates were coated with 100μl 0.05 M carbonate buffer containing 10μl monoclonal anti-S100B (Affiniti Research Products, Exeter, UK). The plates were washed with 0.67 M barbitone buffer containing 5 mM calcium lactate, 0.1% BSA and 0.05% Tween and then blocked with 2% BSA and washed again. Diluted serum (1:1) in 0.67 M barbitone buffer containing 5 mM calcium lactate was added in duplicate. After incubation and wash 0.1% HRP conjugated polyclonal anti-S100B (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used as detecting antibody. The OPD colour reaction was stopped with 1 M hydrochloric acid and the absorbance read at 492 and 405 nm. The antigen concentration was calculated against a standard curve ranging from 0.01 to 2.5 ng/ml.

Statistical analyses

Median, interquartile range and significance of group differences (Mann-Whitney U tests) were evaluated. Changes of serum level over time were examined using variance components regression models of serum response variable on time as predictor, with random subject-specific intercepts and fixed common slopes. Curvature was assessed using a quadratic term in time; modification of curve over time by treatment was assessed using additional terms for treatment and treatment by time interaction in the model. Two sets of treatment terms were used: i) indicators of assigned weekly dose ii) average weekly dose over follow-up (including changes to dose regime) as continuous variable. Modification of the curve over time by MRI variable values were similarly examined using terms for MRI variable and MRI variable by time interaction.

Direct associations between serum level and MRI/clinical variables were examined by regression models of 24 month serum on 24 month MRI variable, adjusting for baseline serum and MRI values (this type of model takes into account change from baseline), with additional terms for treatment and treatment by MRI variable interaction, the latter to assess possible modifications of the relationship by treatment.

Software used were the SPSS software package (version 11.0 for Windows) and Stata 7.0 (Stata Corporation. Stata Statistical Software: Release 7.0. College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Serum S100B between subjects with PPMS and controls

The median and interquartile ranges for all subjects are described in Table 1. There were no significant differences between any of the groups in relation to age. When comparing S100B levels at baseline of subjects with PPMS and controls, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.3).

Table 1.

Age and serial serum S100B levels expressed as median (interquartile range). n = number of subjects; mo, months; N/A, non-applicable.

| Control (n = 14) | Placebo (n = 20) | IFN30 (n = 15) | IFN60 (n = 15) | |

| Male:Female | 6:8 n = 14 | 15:5 n = 20 | 10:5 n = 15 | 7:8 n = 15 |

| Age (years) | 32 (29–44) n = 14 | 43 (36–51) n = 20 | 51 (39–53) n = 15 | 52 (43–54) n = 15 |

| S100B-0mo | 0.08 (0.08–0.10) n = 14 | 0.09 (0.02–0.10) n = 20 | 0.06 (0.04–0.10) n = 12 | 0.07 (0.04–0.10) n = 14 |

| S100B-3mo | N/A | 0.08 (0.05–0.10) n = 20 | 0.06 (0.05–0.10) n = 15 | 0.07 (0.04–0.10) n = 14 |

| S100B-6mo | N/A | 0.10 (0.03–0.20) n = 18 | 0.07 (0.04–0.10) n = 15 | 0.07 (0.04–0.10) n = 14 |

| S100B-9mo | N/A | 0.08 (0.03–0.10) n = 18 | 0.05 (0.02–0.10) n = 15 | 0.06 (0.04–0.10) n = 14 |

| S100B-12mo | N/A | 0.07 (0.03–0.10) n = 17 | 0.08 (0.05–0.10) n = 15 | 0.08 (0.04–0.10) n = 14 |

| S100B-15mo | N/A | 0.07 (0.02–0.10) n = 19 | 0.07 (0.04–0.10) n = 14 | 0.09 (0.04–0.10) n = 14 |

| S100B-18mo | N/A | 0.07 (0.04–0.10) n = 18 | 0.06 (0.02–0.09) n = 13 | 0.09 (0.03–0.20) n = 14 |

| S100B-21mo | N/A | 0.06 (0.05–0.10) n = 18 | 0.08 (0.04–0.10) n = 14 | 0.08 (0.04–0.20) n = 13 |

| S100B-24mo | N/A | 0.07 (0.02–0.10) n = 18 | 0.07 (0.05–0.10) n = 15 | 0.06 (0.04–0.10) n = 13 |

Serum S100B change over time

There was no change over time in the serum S100B levels. The shape of the serum trajectory did not vary between the treatment regimes, i.e. placebo vs. IFN30 vs. IFN60.

Serum S100B versus Clinical and MRI parameters (Table 2)

Table 2.

Serum S100B versus Clinical and MRI variables. Estimated mean change in 24-month serum S100B associated with unit increase in mean value of T1 and T2 lesion load, ventricular and spinal cord volume, adjusted for baseline values of both serum S100B and of MRI parameters. Baseline adjustment ensures that the coefficient assesses the 'effect' of the 24-month MRI parameters value relative to its baseline. * Test of treatment interactions with row variable.

| Variable | Coefficient | P-value | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | P-value for treatment modification*: Assignment average dose | |

| 24 month T1 load | -4 × 10-6 | 0.35 | -1 × 10-5, 4 × 10-6 | 0.76 | 0.59 |

| 24 month T2 load | -3 × 10-6 | 0.16 | -7 × 10-6, 1 × 10-6 | 0.57 | 0.89 |

| 24 month ventricular volume | 7 × 10-7 | 0.75 | -3 × 10-6, 5 × 10-6 | 0.46 | 0.24 |

| 24 month cord volume | -2 × 10-3 | 0.54 | -9 × 10-3, 5 × 10-3 | 0.58 | 0.88 |

There was no evidence that the 24-month serum S100B values were associated with either changes in the T1 or T2 loads, or ventricular or cord volumes at 24 months, after adjusting for the baseline values of each subject. There was no correlation with disease progression on the EDSS. There was also no evidence that these relationships were modified by treatment assignment (intention-to-treat analysis) (Table 2) or the overall average dose, which included the changes to treatment regime (non-intention-to-treat analysis) (Table 2).

Discussion

These results suggest that serum S100B levels in patients with PPMS were not affected by intramuscular IFNβ-1a and that there was no observable change in S100B over time. Furthermore, we did not observe any correlation between S100B levels and clinical disability or between S100B and quantitative MRI measures.

This study therefore suggests Although there is evidence that S100B elevation in MS is related to inflammatory activity [10,11,13], this study has shown that S100B was not sensitive to disease progression in PPMS. This supports the view that PPMS is less inflammatory than other forms of MS and that serum S100B would be ineffective as a surrogate marker of disease progression in this subgroup.

It would be valuable to identify surrogate markers of clinical progression in PPMS to aid the development of effective therapeutic intervention, since clinical trials with a disability endpoint are very large and resource consuming. It is possible that such markers would need to be less related to acute inflammation and more dependant on other neuropathology such as axonal loss and regeneneration.

Contributor Information

Ee Tuan Lim, Email: e.lim@ion.ucl.ac.uk.

Axel Petzold, Email: a.petzold@ion.ucl.ac.uk.

Siobhan M Leary, Email: siobhan_leary@hotmail.com.

Daniel R Altmann, Email: dan.altmann@lshtm.ac.uk.

Geoff Keir, Email: g.keir@ion.ucl.ac.uk.

Ed J Thompson, Email: e.thompson@ion.ucl.ac.uk.

David H Miller, Email: d.miller@ion.ucl.ac.uk.

Alan J Thompson, Email: A.Thomspon@ion.ucl.ac.uk.

Gavin Giovannoni, Email: G.Giovannoni@ion.ucl.ac.uk.

References

- Dayal A, Jensen M, Lledo A, Arnason B. Interferon-gamma-secreting cells in multiple sclerosis patients treated with interferon beta-1b. Neurology. 1995;45:2173–2177. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.12.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato R. S100: a multigenic family of calcium-modulated proteins of the EF-hand type with intracellular and extracellular functional roles. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:637–668. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Study Group on Interferon β-1b in Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Placebo-controlled multicentre randomised trial of interferon β-1b in treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998;352:1491–1497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayo A, Mozo L, Suarez A, Tunon A, Lahoz C, Gutierrez C. Interferon beta-1b treatment modulates TNF alpha and IFN gamma spontaneous gene expression in MS. Neurology. 1999;52:1764–1770. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.9.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AJ, Keir G, Thomspon EJ. A specific and sensitive ELISA for measuring S-100b incerebrospinal fluid. J Immunol Methods. 1997;205:35–41. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(97)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG) Intramuscular interferon-beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:285–294. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary SM, Miller DH, Stevenson VL, Brex PA, Chard DT, Thompson AJ. Interferon beta-1a in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: an exploratory randomised controlled trial. Neurology. 2003;60:44–51. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert D, Waubant E, Burk MR, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL. Interferon beta-1b inhibits gelatinase secretion and in vitro migration of human T cells: a possible mechanism for treatment efficacy in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:846–852. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou J, Gasche Y, Zheng L, Giroud C, Morel P, Clements J, Ythier A, Grau GE. Interferon-β inhibits activated leukocyte migration through human brain microvascular endothelial cell monolayer. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1015–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro AR, Michetti F, Laudisio A, Bergonzi P. Myelin basic protein and S-100 antigen in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis in the acute phase. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1985;6:53–56. doi: 10.1007/BF02229218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michetti F, Massaro A, Russo G, Rigon G. The S-100 antigen in cerebrospinal fluid as a possible index of cell injury in the nervous system. J Neurol Sci. 1980;44:259–263. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(80)90133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panitch H, Hirsch R, Schindler J, Johnson K. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with gamma interferon: exarcebations associated with activation of the immune system. Neurology. 1987;37:1097–1102. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.7.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold A, Eikelenboom MJ, Gveric D, Keir G, Chapman M, Lazeron RH, Cuzner ML, Polman CH, Uitdehaag BM, Thompson EJ, Giovannoni G. Markers for different glial cell responses in multiple sclerosis: clinical and pathological correlations. Brain. 2002;125:1462–1473. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRISMS Study Group Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon β-1a in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998;352:1498–1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S. S100B: pathogenetic and pathophysiologic significance in neurology. Nervenarzt. 1998;69:639–646. doi: 10.1007/s001150050323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuve O, Dooley NP, Uhm JH, Antel JP, Francis GS, Williams G, Yong VW. Interferon β-1b decreases the migration of T lymphocytes in vitro: effects on matrix metalloproteinase-9. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:853–863. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The INFB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1993;43:655–661. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhm JH, Dooley NP, Stuve O, Francis GS, Duquette P, Antel JP, Yong VW. Migratory behaviour of lymphocytes isolated from multiple sclerosis: effects of interferon beta-1b therapy. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:319–324. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199909)46:3<319::AID-ANA7>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]