Abstract

This article describes Health for Hearts United, a longitudinal church-based intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in mid-life and older African Americans. Using community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches and undergirded by both the Socio-ecological Theory and the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change, the 18-month intervention was developed in six north Florida churches, randomly assigned as treatment or comparison. The intervention was framed around three conceptual components: awareness building (individual knowledge development); clinical learning (individual and small group educational sessions); and efficacy development (recognition and sustainability). We identified three lessons learned: providing consistency in programming even during participant absences; providing structured activities to assist health ministries in sustainability; and addressing changes at the church level. Recommendations include church-based approaches that reflect multi-level CBPR and the collaborative faith model.

Keywords: Cardiovascular Disease, Church-based Health, African Americans, Longitudinal Intervention, Community-Based Participatory Research, Older Adults

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to be the leading cause of death in the United States.1 As a group, African Americans have higher age-adjusted morbidity and mortality rates than Caucasians for both heart disease and stroke.1 While a decline in morbidity and mortality rates from heart disease have been noted recently for both groups, African Americans (352.4 men, 248.6 women per 100,000) continue to have higher death rates than Caucasians (271.9 and 181.1, respectively).1 CVD risk is associated with several factors including elevated blood pressure, excess body weight, sedentary lifestyle and diet.1

Healthy People 2020 recommends that community-based approaches be used to reach and improve the health of African Americans and other underserved populations.2 For African Americans, faith-based organizations are key community organizations where participation rates have continued to increase.3 Further, much evidence suggests that health behavior change, such as increased fruit and vegetable consumption, increased physical activity, and improved health status, including lower body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and lower blood pressure, can occur as a result of church-based health programming.4-9 However, church-based health research has several challenges. First, consistent with broader community interventions, few church-based interventions have rigorous outcome evaluation data. Crook and colleagues, for example, in an analysis of published studies of CVD-related interventions with African Americans, showed that, of 524 studies examined, only 33 met the criterion of intervention research.6 Second, church-based interventions often have weak designs, including lack of longitudinal studies that examine sustainability of individual health change and church-based health programming.10 With regard to sustainability, types of approaches to the church-based interventions from the literature include faith-based (emanating from existing committees or groups in the church such as health ministries), faith-placed (emanating from an outside entity), and collaborative (partnerships between churches and outside groups).10, 11 While all three approaches can lead to individual health change, it is unclear which approach(es) are effective in sustaining impactful church-based health.11 Finally, little is known about church-based health programs tailored for mid-life and older African Americans, although this age group is more likely to have higher church attendance than younger age groups.12 To address these issues, intervention studies are needed that focus on mid-life and older African Americans, use rigorous longitudinal evaluation designs, and examine sustainability in individual behavior change and in church health programming.

This article describes Health for Hearts United (HHU), an 18-month longitudinal church-based intervention to reduce CVD risk in mid-life and older African Americans. Specifically, this article: 1) provides background and need for the overall project; 2) presents the intervention, including theoretical and conceptual perspectives, developmental processes, and distinctive features; and 3) discusses lessons learned.

The Reducing CVD Risk Project

The purpose of the Reducing CVD Risk Project was to evaluate the effectiveness of HHU implemented in a two-county area in north Florida.13 The need to develop the project grew out of local community initiatives to form county-based coalitions that included churches in partnership with local universities and health organizations to address health issues in the north Florida region.13 This broader context for the project is consistent with the collaborative approach in working with faith-based organizations. The counties targeted for this project were selected because of the high prevalence of CVD risk factors and mortality rates compared with the overall Florida population. For example, at the time of the study, both counties had a majority of African Americans who had reported their weight as either overweight or obese (60%), consumed less than five vegetables/fruits a day (range from 77% to 82.5%), and reported no moderate (59%-69.4%) or vigorous (75.2%-86.3%) physical activity.14 Further, both counties had a high risk of strokes (203-228 per 100,000 for those aged ≥35 years), a rate that exceeded the state average (181 per 100,000).14 Six churches were recruited to participate in the project, and were randomly assigned as treatment or comparison, stratifying by community within county. Using a quasi-experimental longitudinal design, the study targeted 300 mid-life and older African American members of the churches, including a subsample of 100 participants selected for clinical assessments.13

The Intervention: Health for Hearts United

The development of the HHU intervention was guided by community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches including church steering committees organized in each church, community stakeholder advisory groups in each county, and a research advisory group comprising the investigative team and project staff.13 The name for the intervention, HHU, was identified by one of the community stakeholder advisory groups and then adopted by the church steering committees and other advisory groups.

Theoretical and Conceptual Perspectives

Socioecological (SE) Theory along with the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (TTM) were the theoretical frameworks for the Reducing CVD Risk Project.12,15-17 Levels reflected in SE include intrapersonal (individual characteristics that influence health behavior); interpersonal (group influences such as social networks and social support that help to support healthy behaviors); organizational (policies, facilities and organizational structures); and environment/policy (community or government resources, policies, advocacy).16 Consistent with the intrapersonal level, TTM is an integrative theory that uses individual decision-making processes as a basis to explain intentional behavior change, and is based on the premise that people move through a series of changes in their attempt to change a behavior.17

The HHU intervention reflects these theoretical perspectives, specifically intrapersonal, which includes the baseline and follow-up health behaviors, health status and individual characteristics of church members; interpersonal, which includes the group influences of the church leadership (pastors, treatment church steering committees) that support health behavior change on the part of church members; and organizational, which includes structures (health ministries) and policies (church health policies and practices) that help to sustain church health programming.16,17

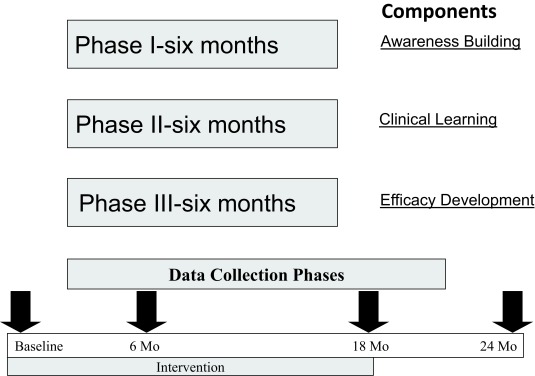

Finally, a three-component conceptual perspective for the intervention was developed based on effectiveness of interventions with African Americans: awareness building (individual knowledge development); clinical learning (individual and small group educational sessions); and efficacy development (recognition and sustainability)6,18-22 (Figure 1). These components reflect the theoretical perspectives of individual, group and organizational levels to promote health behavior change.

Figure 1. Health for Hearts United Model.

Development Processes

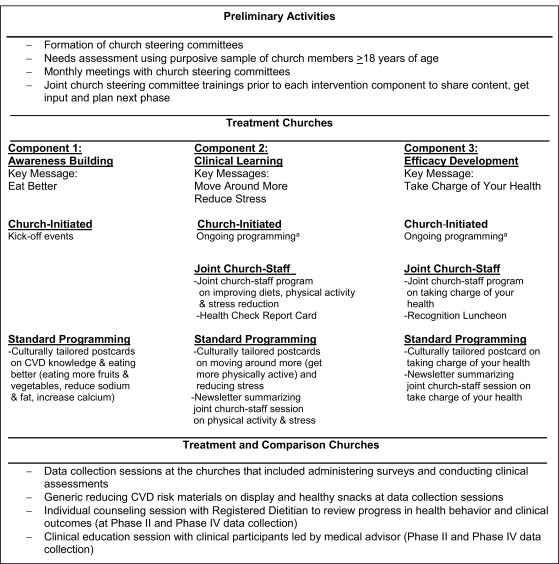

The development of the HHU intervention involved an interactive, iterative process between the project team, the advisory groups and treatment church steering committees, consistent with CBPR approaches. (Figure 2 describes the intervention, including preliminary activities, components of the intervention for the treatment churches, and activities implemented with both treatment and comparison churches.

Figure 2. Description of Health for Hearts United intervention.

a. Ongoing programming referred to any health programs that the treatment churches continued independently during the course of the intervention. Examples included: newsletters initiated by the health ministry; health messages integrated into women’s ministry events; and Health Sundays where health messages were incorporated into services.

With regard to preliminary activities, church steering committees were formed at the treatment churches and initial meetings were held.13 At these meetings, the timeline for the project was discussed and determined. A monthly meeting schedule was adopted for each treatment church. In the initial meetings, a needs assessment was discussed as a best practice for input into the planning process and was offered as a service by the project staff. Each committee decided to have the needs assessment conducted. A brief survey to determine health programming needs, health status and background characteristics of church members was drafted by the project team with input from the treatment church steering committees and then pilot-tested with a small group of African American adults not included in the church sample. The committees and project staff decided to administer the survey to members (aged ≥ 18 years) of the three treatment churches following a church service. Selected results were then shared with the respective church steering committee. Table 1 shows that the majority of participants in the three treatment churches perceived that they, along with someone in their family, had high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes. These data demonstrate that church members’ health status was consistent with county health status data.

Table 1. Perceived health problems of church members, n (%).

| Perceived Health Problem | Church 1, n=71 | Church 2, n=161 | Church 3, n=56 | |||

| Self | Family member | Self | Family member | Self | Family member | |

| High blood pressure | 32 (44.4) | 34(47.2) | 44 (26.8) | 110 (67.1) | 28 (49.1) | 29 (50.9) |

| High cholesterol | 16 (22.2) | 20 (27.8) | 30 (18.3) | 67 (40.9) | 20 (35.1) | 17 (29.8) |

| Diabetes | 16 (22.2) | 30 (41.7) | 17 (10.4) | 101 (61.6) | 17 (29.8) | 27 (47.4) |

| Heart disease | 4 (5.6) | 10 (13.9) | 9 (5.5) | 39 (23.8) | 4 (5.6) | 10 (13.9) |

| Stroke | 2 (2.8) | 9 (12.5) | 6 (3.7) | 46 (28.0) | 2 (2.8) | 9 (12.5) |

| Cancer | 2 (2.8) | 14 (19.4) | 4 (2.4) | 36 (22.0) | 2 (2.8) | 9 (12.5) |

| Sickle cell anemia | 1 (1.4) | 10 (13.9) | 7 (4.3) | 25 (15.2) | 0 (0) | 10 (13.9) |

| HIV/AIDS | 0 (0) | 7 (9.7) | 7 (4.3) | 11 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 7 (9.7) |

Another decision made by the treatment church steering committees was the adoption of the SE and TTM theoretical frameworks and the three-component conceptual model as the framework for the intervention. Finally, joint trainings for the treatment church steering committees were proposed and adopted to help build capacity in health knowledge in the church leaders, get input and debrief regarding project implementation, and provide information for use in planning each component of the intervention.

Distinctive Features

In the planning process with the treatment church steering committees, three distinctive features evolved in the development of the HHU intervention: types of programs; key messages; and materials.

Types of Programs

Four types of programming for treatment and comparison churches were developed: church-initiated programming (treatment only), joint church-project staff programming (treatment only), project staff-initiated standard programming (treatment only), and data collection health promotion (treatment and comparison) (Figure 2). For the most part, all four types of programs were implemented across the three components of the intervention.

Church-initiated Programming

Church-initiated programming was included in the intervention to build capacity among the churches to independently implement health programs.10,23

Joint Programming

Joint programming between the treatment church steering committees and the project team was planned to develop more depth in health knowledge related to reducing CVD risk. The decision was made to hold educational sessions at the local churches, bringing speakers and other resources to the community to demonstrate how to facilitate bringing health resources into the church.10

Standard Programming

To ensure that all participants received consistent CVD-related content, standard programming was initiated that included culturally tailored materials disseminated to participants across the treatment churches.

Data Collection Health Promotion

Both treatment and comparison participants had access to healthy snacks and generic materials on reducing CVD risk during data collection, and participated in counseling sessions with a registered dietitian to compare their data outcomes on selected project outcomes at 6 and 24 months. The clinical subsample treatment and comparison participants also participated in a clinical education session led by the project medical advisor and received their clinical data confidentially.

Key Messages

Four health messages were developed jointly by the treatment church steering committees and integrated into the programming components: Eat Better, Move Around More, Reduce Stress and Take Charge of Your Health.

Materials

Culturally tailored postcards were developed by the project staff to promote and reinforce the key health messages with research participants, using interactive feedback from treatment church steering committee members. In addition to the cards, a newsletter was developed to provide reinforcement of the information presented during church-initiated and joint programming and to ensure all participants received the same evidenced-based content. Finally, a self-monitoring tool called the Health Check Report Card (HCRC) was developed in conjunction with the project; the HCRC measured types of food eaten and amount of physical activity using a pre-determined point system that provided a mechanism for participants to jumpstart health behavior change.24

Intervention Components

Component 1: Awareness Building (Months 1-6)

In the first component of the intervention, organizational meetings for the treatment church steering committees were held to review the overall project and to develop a structure and timeline for getting ongoing input and guidance for development of the intervention, including key messages. As a part of this process, each treatment church steering committee was asked to develop a strategic plan, including mission, vision, goals and activities that provided the foundation for health ministry development. In addition, the first joint project training was held with the steering committees to increase general knowledge regarding CVD and nutrition, and to assist health leaders in promoting the first message regarding “Eat Better.” Church-initiated programming was implemented in this phase with kick-off events to promote CVD awareness and dietary health. In addition, standard programming was initiated with the development of culturally tailored postcards on the following topics: increase CVD knowledge, increase fruit and vegetables, increase calcium, and decrease fat, sodium and sugar. The postcards were mailed to all participants.

Component 2: Clinical Learning (Months 7-12)

The second component of the intervention focused on promoting the key messages of “Move Around More” and “Reduce Stress.” First, trainings were held with the treatment church steering committees to build their capacity in promoting these messages. Training presenters included a licensed psychologist, exercise physiologist, personal trainer, and health leaders from churches with active health ministries that provided ideas on how to incorporate physical activity into church health programming. Second, joint programming (educational sessions) focused on physical activity and messages on how to reduce stress messages; these sessions used the same speakers from the treatment church steering committee trainings. Third, culturally tailored postcards were again developed to promote the messages for this component of the intervention. In addition to the cards, the decision was made with input from the steering committees to develop a newsletter summarizing content from the joint programming sessions and mailed to each participant. This step provided reinforcement of the information presented and ensured that all participants, including those unable to attend, received the same evidenced-based content.

Finally, the health check report card (HCRC) was implemented during this component of the intervention. The steering committees decided to hold a competition among the three treatment churches, using a subcommittee with representatives from each committee to develop the rules for participation. The subcommittee decided that the HCRC was to be used for three weeks, including during a major football classic weekend and Thanksgiving. Those who completed the HCRC were recognized at the third project training, receiving certificates of completion and a small gift. In addition, framed participation certificates were provided for each participating church.

Component 3: Efficacy Development (months 13-18)

In the third component, the final training for the treatment church steering committees was held utilizing roundtable discussion groups to provide feedback on the HCRC and on the progress of the project. This training also served as a planning session to determine next steps for the intervention. Steering committees discussed reinforcing key messages, identifying any additional messages needed, determining sustainability of health ministries, and recognizing project participants. Evolving from these discussions was the fourth health message of “Take Charge of Your Health.”

Joint programming was implemented again with sessions held at the churches focusing on the “Take Charge” message, using health professionals and community representatives to address the key themes of increasing knowledge, using community resources, and becoming empowered. In addition, the second joint programming activity implemented was a Recognition Luncheon held at the end of the third intervention component and planned by a subcommittee representing the treatment steering committees. The purpose of this event was to recognize all treatment participants who had completed data collection phases, and to promote efficacy for, and sustainability of, health behavior change.10 Each participant was individually recognized, receiving a personalized framed certificate and refrigerator magnet with the four health messages highlighted. A motivational speech was provided by a local cardiologist selected by the subcommittee.

Finally, standard programming was again implemented with a culturally tailored postcard and newsletter focusing on the “Take Charge” message mailed to all participants.

Comparison Church Intervention Protocol

At the beginning of the project, the pastors of the three comparison churches identified a health leader to assist the project team in recruiting participants and in conducting the data collection sessions. As described earlier, all comparison church participants had access to healthy snacks and generic materials on reducing CVD risk, participated in sessions led by registered dietitians and, for clinical participants, were invited to participate in clinical education sessions. In addition, meetings were held with the pastors of the comparison churches and their health leaders to begin development of church steering committees. Two project trainings were held on understanding CVD and on health ministry development, with comparison church steering committees developing strategic plans. After all data were collected from comparison church participants, a third project training was held that provided an overview of the intervention components including content on nutrition, physical activity and stress reduction. Culturally tailored materials were distributed at this training.

Fidelity Procedures

Fidelity procedures included ensuring intervention delivery, receipt and enactment.25 Intervention delivery involves: the implementation of the intervention as intended; receipt of intervention are the processes to monitor and ensure that the participants understand the desired intervention-related skills; and enactment is the extent to which the participants actually perform intended intervention skills.25 In the HHU project, delivery consistency procedures included: regular trainings to get input from the treatment church steering committees; holding staff meetings to discuss the input; and then outlining each phase of the intervention (joint programming, standard programming) with a feedback loop to steering committee leadership to ensure the planning appropriately reflected input. Weekly meetings with staff were held throughout the project to debrief as activities were held and to provide rigorous feedback on culturally tailored materials. Intervention receipt procedures included: getting regular feedback from treatment church steering committee leadership as intervention phases were implemented; keeping records of attendance for programming sessions; and assessing the intervention through the self-report questionnaires. The assessment included whether or not the participant attended activities (church-initiated and joint programming) or received materials (postcards, newsletters) and, if attended/received, the extent to which they found the programming/materials useful. Intervention enactment was determined through completion of the four phases of data collection.

Because the purpose of this article is to describe the intervention, including developmental processes, we provide illustrations of how fidelity procedures were tracked for the first two procedures: delivery and receipt. Future articles will provide a more thorough process evaluation for the intervention. With regard to intervention delivery, the discussions by treatment church steering committees during the training in component 3 of the intervention demonstrate the feedback loop from the community to project staff. Tables 2 and 3, respectively, show examples of intervention receipt: records of attendance for programming sessions; and data regarding receipt and usefulness of the newsletters.

Table 2. Attendance of church participants in intervention components, n (%.

| Church | Participant Attendance in Intervention Components | ||

| Awareness building | Clinical learning | Efficacy development | |

| Church-initiated kick off | Joint program | Joint program | |

| Church 1a | 20(51.2) | 21(39.6) | 11(22.9) |

| Church 2b | 16(55.1) | 13(36.1) | 11(26.8) |

| Church 3c | 19(54.2) | 17(40.4) | 20(48.7) |

a. n=39, 53 and 48, respectively.

b. n=29, 36 and 41,respectively.

c. n=35, 42 and 41,respectively.

Table 3. Receipt and perceived usefulness of newsletter.

| Newsletters | Receipt of Newsletter by Churcha, n (%) | Perceived usefulness | |||||||

| Church 1 | Church 2 | Church 3 | Total | ||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | M (SD) | |

| Increase physical activity & reduce stress | 18 (48.6) | 19 (51.3) | 21 (72.4) | 8 (27.6) | 30 (85.7) | 5 (14.3) | 69 (68.3) | 32 (31.7) | 4.6 (.75) |

| Take charge of your health | 25 (67.5) | 12 (32.5) | 20 (68.9) | 9 (31.1) | 29 (85.2) | 5(14.8) | 74(74.0) | 26(26.0) | 4.6 (.71) |

a. Because this was a longitudinal study, number of participants varied by data collection phase. Also, participants could enter the project at either phase 1 or phase 2. Thus, the total sample possible were: phase 1 (n=103), phase 2 (n=131) and phase 3 (n=121).

Challenges and Lessons Learned

Several challenges were addressed in the development and implementation of the HHU intervention, providing lessons learned. Three key challenges encountered included: a) lack of consistent involvement by participants in intervention programming; b) sustainability of health ministries; and c) overcoming changes at the church level. Lack of consistent involvement by participants in intervention programming was especially noted as the clinical learning component was implemented. As shown in Table 2, the percent of participant attendance at the program sessions decreased for the most part across the three components (awareness building, 51.2%, 55.1%, and 54.2%; clinical learning 39.6%, 36.1% and 40.4%; efficacy development, 22.9%, 26.8%, and 48.7%). These results occurred even though we initiated a very thorough communication strategy that worked very well with getting participants to data collection sessions.13 The concern by project staff was that this lack of participation would affect the efficacy of the intervention in that content delivered would be inconsistent, thus affecting learning and the move toward health behavior change. Mid-course corrections during the implementation of an intervention are considered a best practice in process evaluation. For example, the FORECAST model incorporates these mid-course corrections as markers, measures and meaning.26 Markers are short-term steps that can assess incremental achievement in implementing the intervention; measures assess whether markers are accomplished by a certain timeline; and meaning provides quality standards or benchmarks for implementation of markers.26 Thus, as a marker, we decided to develop the newsletter following each program session in both components 2 and 3 to ensure that all participants received the content on a consistent basis. The newsletters were mailed to all participants in the treatment churches two to three weeks following each joint programming session. To evaluate whether the newsletter was received (yes or no) and perceived as useful (1=not very useful, 5=very useful), we included these items in the questionnaire in phase 3. The results (Table 3) showed that the majority of the participants responding to the question remembered receiving the newsletters (68.3%, increasing physical activity & reducing stress; 74.0%, taking charge of your health), and most of the data by church revealed these same trends. Further, those responding perceived the two newsletters as very useful (4.6±.75, 4.6±.71, respectively). These data served as measure and meaning in that we were able to develop a timely assessment of the newsletter to determine if this mid-course correction would enhance intervention implementation. The findings suggest that the newsletters may have helped in delivering the content dosage for the project. However, ultimately, the effectiveness study will determine whether the intervention achieved the desired goals related to changes in health behavior and health status.

The second challenge of sustaining health ministries was noted as we moved into components 2 and 3. Although component 1 involved the development of health ministries with planning documents generated by each church health ministry, there was unevenness in how the health ministries were being implemented due to a variety of issues related to leadership, commitment and broader church concerns. Not all of these challenges were resolved. However, we were able to develop strategies to improve communication and to further build capacity in health ministry members. For example, we held regular meetings with each health ministry that helped us to continue to gain input on the intervention as we prepared for the next phase. At these meetings, we got debriefings from the health ministry on opportunities and challenges in health ministry development and provided feedback and encouragement to continue the work. In addition, we developed a sequence of “Meet & Greet” events (brief 1.5-hour after-work receptions at a local hotel accessible to both counties in September or October) and a project training in the winter (half-day session in January or February) that brought all treatment steering committees across churches together and provided opportunities at these sessions for getting input, identifying challenges and sharing of ideas. In general, these three activities—regular meetings with health ministries, Meet & Greet events, and project trainings for all treatment church steering committees – helped to establish bonds across health ministries and assisted with problem-solving.

The third challenge of changes at the church level emerged as we moved into component 3 of the intervention when one of the treatment churches began to have some internal disagreements that affected the performance of church ministries, including the health ministry. We had no way of resolving the problems but we had to determine our modus operandi as a project staff. We decided that our commitment was to the participants regardless of their position on the issues. Thus, we communicated with them about events directly and engaged an associate pastor supported by all church members to attend sessions on behalf of the pastor. In some cases, we held joint program sessions with one of the other treatment churches located nearby. This was helpful since, under these circumstances, some church members did not feel comfortable attending their old church. Thus, through these efforts, we were able to continue the project with church members and then engage the new pastor once the issues were resolved.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This article describes Health for Hearts United (HHU), a theory-driven, 18-month longitudinal church-based intervention to reduce CVD risk in mid-life and older African Americans. Lessons learned suggest that, through the intervention, the project team was able to provide consistency in programming even during participant absences, developed structured activities to assist health ministries in sustainability, and addressed changes at the church level. The next step will be to determine the extent to which HHU is effective in reducing cardiovascular disease risk in mid-life and older African Americans.

This article also provides the basis for broader recommendations for researchers seeking to address CVD risk or other health issues using church-based interventions. First, we found it beneficial to implement multi-level CBPR strategies as a tool in developing church-based interventions.27-29 We found, for example, that having meetings of the treatment church steering committees at both the church and project levels allowed for two perspectives to view the project. At the church level, we learned more about the church context for health that was either facilitating or perhaps hindering participants in their completion of the project. At the same time, the project-level activities (eg, trainings) helped us understand cross-church similarities and differences. Consistent with CBPR principles, integration of diverse perspectives and identification of shared commitments and priorities served as a foundation for partnership building and provided a broader context for problem solving.27-29 Thus, through using this multi-level CBPR approach, we were better able to understand the real-world challenges faced by participants in completing health-related activities for the project and the difficulties and yet resilience of health ministries and the churches themselves.

Second, consistent with the literature, we noted the strength of the collaborative approach to intervention development in addition to the faith-based and faith-placed models.10,11 The HHU intervention evolved from a broader community effort to develop church coalitions in partnership with universities and health organizations to promote health in a multi-county area of north Florida. As a part of HHU, we helped churches develop health ministries that would have an opportunity to connect to this broader community effort. Thus, from our perspective, the collaborative approach was a preferred model because the church coalitions provide an ongoing organizational framework to assist the churches in continuing their health programming. Clearly, work is needed to thoroughly evaluate these approaches, keeping in perspective both research and community needs.

Our work has demonstrated that a church-based intervention to reduce CVD risk in African Americans can be developed using CBPR and a collaborative approach. Future efforts will need to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention in relation to changes in individual health as well as the extent to which this collaborative approach facilitated sustainability of church-based health.

Acknowledgments and Compliance with Ethical Standards

This project was supported by Award Number R24MD002807 (P.I. Ralston) from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIMHD. Appreciation is expressed to the pastors and health leaders from the participating churches and to project staff and students in the development of the Health for Hearts United intervention.

There are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors. Our research was approved by the Florida State University Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all treatment church participants for the needs assessment.

References

- 1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;132:e1-e324. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2020 Website. https://www.healthypeople.gov/. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 3. Barnes S. Enter into his gates: an analysis of Black church participation patterns. Sociol Spectr. 2009;29(2):173-200. 10.1080/02732170802584351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baruth M, Wilcox S, Laken M, Bopp M, Saunders R. Implementation of a faith-based physical activity intervention: insights from church health directors. J Community Health. 2008;33(5):304-312. 10.1007/s10900-008-9098-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campbell MK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Symons M, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevention of cancer: the Black Churches United for Better Health project. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1390-1396. 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crook ED, Bryan NB, Hanks R, et al. A review of interventions to reduce health disparities in cardiovascular disease in African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):204-208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peterson J, Atwood JR, Yates B. Key elements for church-based health promotion programs: outcome-based literature review. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(6):401-411. 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19602.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilcox S, Laken M, Bopp M, et al. Increasing physical activity among church members: community-based participatory research. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(2):131-138. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yanek LR, Becker DM, Moy TF, Gittelsohn J, Koffman DM. Project Joy: faith based cardiovascular health promotion for African American women. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(90001)(suppl 1):68-81. 10.1093/phr/116.S1.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campbell M, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: Lessons learned. Annu Review of Publ Health; 2007:213-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry J. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):1030-1036. 10.2105/AJPH.94.6.1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallup. Seven in 10 Americans are very or moderately religious. Website: http://www.gallup.com/poll/159050/seven-americans-moderately-religious.aspx?utm_source=church%20attendance%20by%20age&utm_medium=search&utm_campaign=tiles. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 13. Ralston PA, Lemacks JL, Wickrama KK, et al. Reducing cardiovascular disease risk in mid-life and older African Americans: a church-based longitudinal intervention project at baseline. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;38(1):69-81. 10.1016/j.cct.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Florida Department of Health Florida behavioral risk factor data. Website. http://www.floridacharts.com/charts/brfss.aspx, Accessed April 25, 2015.

- 15. Yeary KH, Klos LA, Linnan L. The examination of process evaluation use in church-based health interventions: a systematic review. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(4):524-534. 10.1177/1524839910390358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351-377. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390-395. 10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Croft JB, Temple SP, Lankenau B, et al. Community intervention and trends in dietary fat consumption among black and white adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94(11):1284-1290. 10.1016/0002-8223(94)92461-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaul L, Nidiry JJ. Management of obesity in low-income African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 1999;91(3):139-143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumanyika SK, Cook NR, Cutler JA, et al. ; Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group . Sodium reduction for hypertension prevention in overweight adults: further results from the Trials of Hypertension Prevention Phase II. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19(1):33-45. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rankins J. Modified soul: A culturally sensitive process model for helping African Americans achieve dietary guidelines for cancer prevention. Ecol Food Nutr. 2002;41:181-201. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Resnicow K, Wallace DC, Jackson A, et al. Dietary change through African American churches: baseline results and program description of the eat for life trial. J Cancer Educ. 2000;15(3):156-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carter-Edwards L, Jallah YB, Goldmon MV, Roberson JT Jr, Hoyo C. Key attributes of health ministries in African American churches: an exploratory survey. N C Med J. 2006;67(5):345-350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McDole M, Ralston PA, Coccia C, Young-Clark I. The development of a tracking tool to improve health behaviors in African American adults. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):171-184. 10.1353/hpu.2013.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, et al. ; Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the NIH Behavior Change Consortium . Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):443-451. 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Katz J, Wandersman A, Goodman RM, Griffin S, Wilson DK, Schillaci M. Updating the FORECAST formative evaluation approach and some implications for ameliorating theory failure, implementation failure, and evaluation failure. Eval Program Plann. 2013;39:42-50. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andrews JO, Tingen MS, Jarriel SC, et al. Application of a CBPR framework to inform a multi-level tobacco cessation intervention in public housing neighborhoods. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50(1-2):129-140. 10.1007/s10464-011-9482-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Coombe CM, et al. A community-based participatory planning process and multilevel intervention design: toward eliminating cardiovascular health inequities. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(6):900-911. 10.1177/1524839909359156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frerichs L, Lich KH, Dave G, Corbie-Smith G. Integrating systems science and community-based participatory research to achieve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):215-222. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]