Abstract

Biological variability has confounded efforts to confirm the role of PREX2 mutations in melanoma.

Research Organism: Mouse

Related research articles Horrigan SK, Courville P, Sampey D, Zhou F, Cai S, Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology. 2017. Replication Study: Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations. eLife 6:e21634. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21634

Chroscinski D, Sampey D, Hewitt A, Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology. 2014. Registered Report: Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations. eLife 3:e04180. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04180

Melanoma is associated with DNA damage and genomic alterations caused by ultraviolet light. In 2012, as part of efforts to better understand the causes of melanoma, researchers at the Broad Institute, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and a number of other institutes reported the results of whole genome sequencing of 25 human metastatic melanomas (Berger et al., 2012). This analysis discovered an average of 97 structural rearrangements of the genome per tumor, and some 9,653 mutations of various types in 5,712 genes. A number of known melanoma oncogenes were identified, including BRAFV600E (in 64% of tumors) and mutated NRAS (36%). The analysis also found that a significant fraction of tumors contained rearrangements and mutations of a gene called PREX2, and experiments confirmed that cancer-associated mutations of PREX2 promoted the growth of human melanoma cells in mice.

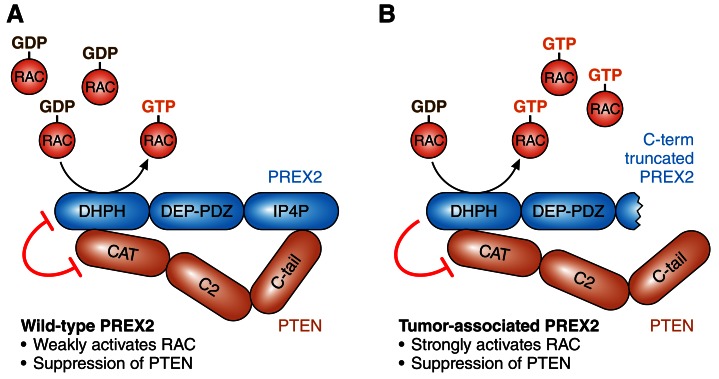

It has been known for a number of years that PREX2 is a GTP/GDP exchange factor that inhibits a tumor suppressor protein called PTEN, and that this process can promote tumorigenesis by activating the PI3K signaling pathway (Fine et al., 2009; Hodakoski et al., 2014; Figure 1A). More recently it has been shown that PTEN can inhibit PREX2, and that this can stop tumor cells invading tissue by preventing the activation of an enzyme called RAC (Mense et al., 2015). Moreover, cancer-associated mutations in PREX2 disrupt these mutual inhibition processes: mutated PREX2 can still inhibit PTEN, but PTEN cannot inhibit mutated PREX2 (Mense et al., 2015; Figure 1B). All this work supports the conclusion that the over-expression of PREX2 can increase PI3K-dependent tumor growth (Fine et al., 2009), and that mutated PREX2 promotes tumorigenesis by increasing RAC-dependent invasiveness (Mense et al., 2015).

Figure 1. The roles of PREX2 and PTEN.

(A) PREX2 (blue) is a GTP/GDP exchange factor that activates a GTPase called RAC. PTEN (brown) is a lipid phosphatase that suppresses tumors by inhibiting PI3K signaling (not shown). The interaction of PREX2 and PTEN (via their DHPH and CAT domains respectively) suppresses the catalytic activity of both. (B) Cancer-associated mutations in PREX2 (or C-terminal truncation of PREX2, as shown here) do not interfere with its ability to activate RAC or its ability to inhibit PTEN. However, PTEN is unable to inhibit mutated PREX2. Therefore mutations in PREX2 can lead to cancer by increasing both RAC and PI3K signaling. PREX2: phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate-dependent RAC exchange factor 2. PTEN: phosphatase and tensin homolog. RAC: RAS-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate.

As part of the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology, Chroscinski et al. published a Registered Report which explained in detail how they would seek to replicate selected experiments from Berger et al. (Chroscinski et al., 2014). The results of these experiments have now been published as a Replication Study (Horrigan et al., 2017).

The original paper by Berger et al. contained two major conclusions. First, PREX2 was identified as a frequently mutated gene in human melanoma. The Reproducibility Project did not attempt to replicate this finding, but subsequent studies have reported the frequency of PREX2 mutations in human melanoma (Hodis et al., 2012; Krauthammer et al., 2012; Marzese et al., 2014; Ni et al., 2013; Turajlic et al., 2012), including meta-analysis of 241 melanomas (Xia et al., 2014). Second, mutation of PREX2 can accelerate human melanoma growth. The Reproducibility Project did attempt to replicate the mouse xenograft studies that support this second conclusion.

Berger et al. expressed six different mutated PREX2 proteins in TERT-immortalized human melanoma cells. These cells were transplanted into immuno-deficient mice. Control studies were performed using cells expressing either wild-type PREX2 or green fluorescent protein (GFP). Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that most of the mice injected with cells expressing wild-type PREX2 or GFP exhibited tumor-free survival for more than ten weeks. In contrast, cancer-associated mutations in PREX2 significantly reduced tumor-free mouse survival (Figures 3B and S6 of Berger et al.). The work of Berger et al. supported the conclusion that cancer-associated PREX2 mutations can promote the growth of human melanoma cells.

Attempts to replicate these xenograft experiments were confounded by a serious technical problem. The tumors grew rapidly in the control experiments (the median time for tumor-free survival was one week) and any differences in tumor-free survival for the controls and the mice injected with cells expressing mutated PREX2 were not statistically significant (Horrigan et al., 2017). Consequently, no conclusions could be drawn concerning the possible contribution of PREX2 mutations to melanoma growth.

This Replication Study represents a cautionary tale concerning the impact of biological variability on experimental design. While strenuous efforts were made to precisely copy the experimental conditions employed in the original study, the xenografts in the Replication Study behaved in a fundamentally different way to those in the original study. The mechanistic basis for the observed differences is unclear. Presumably, there was a difference in the melanoma cells and/or the mice. Although the cells were obtained from the same source, small differences in culture conditions or passage history could have contributed to differences between the studies. Similarly, although the mice were obtained from the same source, housing the animals in a different facility may have contributed to differences between the studies.

A key lesson to be drawn from this experience is that biological variability is a critical factor in experimental design. Pilot studies to explore biological variation would have allowed this Replication Study to be redesigned to inject fewer melanoma cells and thus delay tumor growth. Biological variability means, therefore, that direct replication of a reported study might not always be the best way to assess reproducibility in certain fields.

Questions remain concerning the role of PREX2 mutations in cancer. It is established that PREX2 can be mutated in melanoma and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (Berger et al., 2012; Waddell et al., 2015), and that cancer-associated PREX2 mutations can promote both tumorigenesis in vivo (Lissanu Deribe et al., 2016) and tumor cell invasiveness (Mense et al., 2015). However, wild-type PREX2 can also promote tumor growth by suppressing PTEN activity and increasing PI3K signaling (Fine et al., 2009). There is a clear need for further mechanistic studies to explore the role of PREX2 and mutations of PREX2 in cancer.

Note

Roger J Davis was the eLife Reviewing Editor for the Registered Report (Chroscinski et al., 2014) and the Replication Study (Horrigan et al., 2017).

Competing interests

The author declares that no competing interests exist.

References

- Berger MF, Hodis E, Heffernan TP, Deribe YL, Lawrence MS, Protopopov A, Ivanova E, Watson IR, Nickerson E, Ghosh P, Zhang H, Zeid R, Ren X, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko AY, Wagle N, Sucker A, Sougnez C, Onofrio R, Ambrogio L, Auclair D, Fennell T, Carter SL, Drier Y, Stojanov P, Singer MA, Voet D, Jing R, Saksena G, Barretina J, Ramos AH, Pugh TJ, Stransky N, Parkin M, Winckler W, Mahan S, Ardlie K, Baldwin J, Wargo J, Schadendorf D, Meyerson M, Gabriel SB, Golub TR, Wagner SN, Lander ES, Getz G, Chin L, Garraway LA. Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations. Nature. 2012;485:502–506. doi: 10.1038/nature11071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chroscinski D, Sampey D, Hewitt A, Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology Registered Report: Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations. eLife. 2014;3:e04180. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine B, Hodakoski C, Koujak S, Su T, Saal LH, Maurer M, Hopkins B, Keniry M, Sulis ML, Mense S, Hibshoosh H, Parsons R. Activation of the PI3K pathway in cancer through inhibition of PTEN by exchange factor P-REX2a. Science. 2009;325:1261–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1173569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodakoski C, Hopkins BD, Barrows D, Mense SM, Keniry M, Anderson KE, Kern PA, Hawkins PT, Stephens LR, Parsons R. Regulation of PTEN inhibition by the pleckstrin homology domain of P-REX2 during insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis. PNAS. 2014;111:155–160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213773111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov GV, Arold ST, Imielinski M, Theurillat JP, Nickerson E, Auclair D, Li L, Place C, Dicara D, Ramos AH, Lawrence MS, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Voet D, Saksena G, Stransky N, Onofrio RC, Winckler W, Ardlie K, Wagle N, Wargo J, Chong K, Morton DL, Stemke-Hale K, Chen G, Noble M, Meyerson M, Ladbury JE, Davies MA, Gershenwald JE, Wagner SN, Hoon DS, Schadendorf D, Lander ES, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Garraway LA, Chin L. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan SK, Courville P, Sampey D, Zhou F, Cai S, Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology Replication Study: Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations. eLife. 2017;6:e21634. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauthammer M, Kong Y, Ha BH, Evans P, Bacchiocchi A, McCusker JP, Cheng E, Davis MJ, Goh G, Choi M, Ariyan S, Narayan D, Dutton-Regester K, Capatana A, Holman EC, Bosenberg M, Sznol M, Kluger HM, Brash DE, Stern DF, Materin MA, Lo RS, Mane S, Ma S, Kidd KK, Hayward NK, Lifton RP, Schlessinger J, Boggon TJ, Halaban R. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic RAC1 mutations in melanoma. Nature Genetics. 2012;44:1006–1014. doi: 10.1038/ng.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissanu Deribe Y, Shi Y, Rai K, Nezi L, Amin SB, Wu CC, Akdemir KC, Mahdavi M, Peng Q, Chang QE, Hornigold K, Arold ST, Welch HC, Garraway LA, Chin L. Truncating PREX2 mutations activate its GEF activity and alter gene expression regulation in NRAS-mutant melanoma. PNAS. 2016;113:E1296–E1305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513801113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzese DM, Scolyer RA, Roqué M, Vargas-Roig LM, Huynh JL, Wilmott JS, Murali R, Buckland ME, Barkhoudarian G, Thompson JF, Morton DL, Kelly DF, Hoon DS. DNA methylation and gene deletion analysis of brain metastases in melanoma patients identifies mutually exclusive molecular alterations. Neuro-Oncology. 2014;16:1499–1509. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mense SM, Barrows D, Hodakoski C, Steinbach N, Schoenfeld D, Su W, Hopkins BD, Su T, Fine B, Hibshoosh H, Parsons R. PTEN inhibits PREX2-catalyzed activation of RAC1 to restrain tumor cell invasion. Science Signaling. 2015;8:ra32. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni TK, Landrette SF, Bjornson RD, Bosenberg MW, Xu T. Low-copy piggyBac transposon mutagenesis in mice identifies genes driving melanoma. PNAS. 2013;110:E3640–3649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314435110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turajlic S, Furney SJ, Lambros MB, Mitsopoulos C, Kozarewa I, Geyer FC, Mackay A, Hakas J, Zvelebil M, Lord CJ, Ashworth A, Thomas M, Stamp G, Larkin J, Reis-Filho JS, Marais R. Whole genome sequencing of matched primary and metastatic acral melanomas. Genome Research. 2012;22:196–207. doi: 10.1101/gr.125591.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell N, Pajic M, Patch AM, Chang DK, Kassahn KS, Bailey P, Johns AL, Miller D, Nones K, Quek K, Quinn MC, Robertson AJ, Fadlullah MZ, Bruxner TJ, Christ AN, Harliwong I, Idrisoglu S, Manning S, Nourse C, Nourbakhsh E, Wani S, Wilson PJ, Markham E, Cloonan N, Anderson MJ, Fink JL, Holmes O, Kazakoff SH, Leonard C, Newell F, Poudel B, Song S, Taylor D, Waddell N, Wood S, Xu Q, Wu J, Pinese M, Cowley MJ, Lee HC, Jones MD, Nagrial AM, Humphris J, Chantrill LA, Chin V, Steinmann AM, Mawson A, Humphrey ES, Colvin EK, Chou A, Scarlett CJ, Pinho AV, Giry-Laterriere M, Rooman I, Samra JS, Kench JG, Pettitt JA, Merrett ND, Toon C, Epari K, Nguyen NQ, Barbour A, Zeps N, Jamieson NB, Graham JS, Niclou SP, Bjerkvig R, Grützmann R, Aust D, Hruban RH, Maitra A, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Wolfgang CL, Morgan RA, Lawlor RT, Corbo V, Bassi C, Falconi M, Zamboni G, Tortora G, Tempero MA, Gill AJ, Eshleman JR, Pilarsky C, Scarpa A, Musgrove EA, Pearson JV, Biankin AV, Grimmond SM, Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Jia P, Hutchinson KE, Dahlman KB, Johnson D, Sosman J, Pao W, Zhao Z. A meta-analysis of somatic mutations from next generation sequencing of 241 melanomas: a road map for the study of genes with potential clinical relevance. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2014;13:1918–1928. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]