Abstract

BACKGROUND

The purpose of this study was to describe a single institution’s experience with adult intussusception and determine how this was influenced by evolving computed tomography (CT) technology.

METHODS

Adults treated between 1978 and 2013 for intussusception were reviewed. CT utilization and utilization of multislice technology over time were determined. Sensitivity of CT was calculated.

RESULTS

A total of 318 patients were identified. CT utilization was 72% and it increased over time. The number of channels ranged from 1 to 128. CT sensitivity was greater than 85% for single and multislice scanners. A lead point was identified in 69% of patients and a malignancy in 40%. Surgical exploration was required in 60% of patients and 40% were managed nonoperatively.

CONCLUSIONS

The diagnosis of intussusception in adults is increasing over time, particularly idiopathic intussusception. This is associated with increased utilization of highly sensitive CT technology, which facilitates the safe nonoperative management in many patients.

Keywords: Adult intussusception, Computed tomography

Intussusception, or telescoping of a proximal segment of intestine (ie, the intussusceptum) into a more distal segment (intussuscipiens), is the most common cause of obstruction in patients younger than 5 years of age.1 It is rare, however, in the adult population, as only 5% of cases occur in patients aged older than 18 years.2,3 Although pediatric patients may present with the classic triad of currant jelly stools, colicky abdominal pain, and a palpable abdominal mass, adults typically present with obstructive symptoms.4,5 Diagnosis is increasing because of widespread availability and use of computed tomography (CT), which identifies intussusception as a sausage—shaped mass with a target sign. Intussusception in adults has traditionally been highly associated with a malignant lead point and, thus, required surgical exploration.6

This belief has been questioned recently given the rapid advancement in CT technology over the past 30 years. CT technology has evolved over the years by the introduction of multislice CT scans, with a sensitivity of 58% to 100% and specificity of 57% to 71% in recognizing the intussusception.3,7,8 Given this fact, transient and asymptomatic intussusceptions without a lead point have been recognized more frequently as well. We aimed in this study to describe the etiology, diagnosis, and management of intussusception in adults, with emphasis on the role of CT scan technology advancement.

Patients and Materials

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained to perform a review of patients diagnosed with intussusception in our institution between 1978 and 2013 using the Mayo Clinic Life Sciences Services/Data Discovery Query Builder. It is maintained collaboratively with IBM, Armnonk, NY by dedicated information technologists, regularly audited, and validated in the literature as accurate for International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9) searches.9 The Data Discovery Query Builder was queried for ICD-9 code for intussusception (560.0). A formal review of patients’ clinical charts was done to collect data that included demographic features of age and sex, as well the presenting signs and symptoms, method of diagnosis, radiological findings, method of management (surgical vs nonsurgical), pathological and surgical findings, and duration of follow-up. Patients were excluded if they had rectal intussusception and those who had intussusception related to their stoma or after intestinal intubation. Transient intussusceptions were defined as asymptomatic intussusceptions noted on CT imaging, which were not present on subsequent imaging. Lead points were verified with CT findings and/or surgical findings and classified etiology: tumor (benign vs malignant), inflammatory, adhesive, foreign body, and idiopathic. The number of data channels (slices) for each CT study was also identified when available. This information was first available in 1995. Patients were categorized according to the site of intussusception:

Small bowel to small bowel;

Ileocolic where the ileum intussuscepts through a stationary ileocecal valve;

Ileocecal where the ileocecal valve is part of the intussusceptum;

Colocolic.

Continuous variables were presented as mean (ranges) and categorical variables as percentages. True positive CT results for intussusception and false negative CT results were used to calculate the sensitivity of CT. Trends were evaluated using the Cochran Armitage Trend Test. Statistical significance was set at P value less than .05.

Results

A total of 318 patients were identified with a mean age of 51 years (range 18 to 94), of whom 57% were women (n = 184). The most common presenting symptoms were abdominal pain (77%, n = 245), complete obstruction (27%, = 87), partial obstruction (15%, = 47), heme-positive stool (12%, = 39), and a palpable mass (8%, = 25). Forty-five patients were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis (14%). Of the 229 patients (72%) who underwent CT, 206 (65%) had findings positive for intussusception on the scan. The remaining 112 patients were diagnosed by endoscopy (16%, = 51), intraoperative findings (14%, = 45), small bowel contrast study (3%, = 9), and magnetic resonance imaging (2%, = 7). The 45 asymptomatic patients had the diagnosis found incidentally on CT (n = 33), small bowel contrast studies (n = 3), endoscopy (n = 7), or operative exploration (n = 2) for presumed other etiologies.

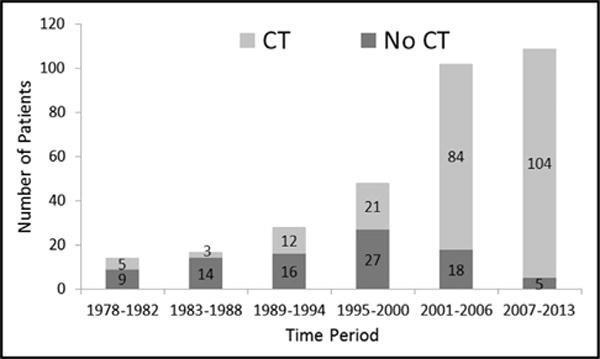

The frequency of intussusception increased with time (Fig. 1), and there was a significant trend toward increased CT utilization over time (P <.001). The number of channels (slices) of the CT scans was available for 153 of the 209 patients who underwent CT scan in 1995 or later. CT technology used in patients ranged from single slices to 128-slice scanners. The use of multislice technology increased with time, with most patients from 2007 to 2013 undergoing 64- or 128-slice scans (Table 1). Increasing resolution, however, did not appear to impact sensitivity of the test, which was 86% for single slice scans, 93% for 4 slice, 100% for 8 slice, 97% for 16 slice, 93% for 64 slice, and 85% for 128 slice scans. False negatives (CT scans that failed to show intussusception) occurred in 23 patients who went on to have intussusception diagnosed by contrast study (n = 6), endoscopy (n = 3), and intraoperatively (n = 14).

Figure 1.

Both the frequency of intussusception and the utilization of CT increased over time.

Table 1.

Utilization of advancing CT technology over time

| Year | Number of slices

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 64 | 128 | N/A | |

| 1995–2000 (n = 21) | 3 (14%) | 4 (19%) | 0 | 2 (10%) | 0 | 0 | 12 (57%) |

| 2001–2006 (n = 84) | 4 (5%) | 26 (31%) | 13 (16%) | 15 (18%) | 6 (7%) | 0 | 20 (24%) |

| 2007–2013 (n = 104) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 (20%) | 37 (36%) | 22 (21%) | 24 (23%) |

CT, computed tomography; N/A, not applicable (refers to those patients without CT specifications available).

The site of the intussusception was most commonly confined to the small bowel (75%, n = 230), followed by colocolic in 14% (n = 43), ileocecal in 8% (n = 26), and the least common site was ileocolic in 5% (n = 19). Lead points were identified in 220 patients (69%). A tumor was identified as the lead point for the intussusception in 128 patients (40%), of which 59 (19%) were malignant and 69 (21%) were benign. Of the malignant tumors, 34 (58%) were primary to the intestine, while the remainder were metastatic (42%, n = 25). Other causes of intussusception included adhesions (15%, n = 47), inflammatory processes (ie, Crohn’s disease, celiac sprue, appendicitis, or other infections; 11%, n = 35), Meckel’s diverticulum (2%, = 5), and ischemic bowel (2%, n = 5). Twenty patients (8%) had a history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Most (60%) involved the roux limb or jejunojejunostomy, while others involved the common channel or the location in the small bowel could not be pinpointed on CT. Nineteen of the 20 patients were diagnosed on CT scan, while 1 was diagnosed on small bowel contrast study. Of the 15 patients who underwent operative exploration, intussusception was found intraoperatively in 5 patients while the remaining 10 had spontaneous reduction before exploration.

Surgical exploration was performed in 192 (60%) patients, of whom 44 (14%) was performed laparoscopically and 148 (47%) performed in an open fashion. Of those patients who underwent exploration, 123 (39%) underwent primary resection, 19 (6%) underwent reduction alone, 16 (5%) underwent reduction followed by resection, 11 (4%) underwent lysis of adhesions without the need for resection or reduction, and the remaining 23 (7%) patients had nontherapeutic explorations. Of the remaining 126 (40%) patients diagnosed with intussusception who did not undergo surgical exploration, 15 had colonoscopic decompression and polypectomy, 1 underwent colonoscopic decompression alone, and the remaining 110 (35%) patients’ intussusception resolved without intervention.

The mean follow-up of the patients was 64 months (range 0 to 1,223 months). There were 24 patients (7.5%) with a recurrence. Of these, 21 (88%) involved the small bowel, 2 were colocolic, and 1 was ileocecal. Recurrences were at the site of initial intussusception. Fifteen of the 24 recurrences were managed surgically (9 resections, 6 reductions). One patient with celiac disease had several recurrences that were all managed nonoperatively. Mortality within 30 days of diagnosis was 1.5%.

Comments

Intussusception in adults is a rare entity that has traditionally required operative exploration when suspected.6,8 This dogma has been called into question by evidence that intussusceptions identified by CT scanning but not associated with a lead point or bowel obstruction may be safely managed nonoperatively.3,10 Unfortunately, data are limited to small institutional cohorts and, thus, no standard of care has been defined. In this study, we examined our experience of 318 adults with intussusception with focus on the role of multislice CT technology over time.

Briefly, many of the findings of this study are consistent with existing literature. Intussusception in adults most commonly presents with abdominal pain and symptoms of obstruction. The small bowel is more frequently affected than the colon, although intussusception involving the colon is more likely to be malignant. Less than half of the patients had a malignant etiology of intussusception, supporting the growing body of literature, which does not recommend mandatory operative exploration of all intussusceptions.3,10,11 Furthermore, more than a third of patients were managed nonoperatively with resolution of intussusception with acceptable recurrence rates. As bariatric procedures increase, more intussusceptions involving roux limbs are expected. In this study, 20 patients had intussusception attributed to the roux limb. Intussusception should then be in the differential diagnosis for patients with previous Roux-en-Y gastric bypass who present with abdominal pain or obstructive symptoms.

As expected, CT utilization in the diagnosis of intussusception in this study increased over time. The widespread availability of CT scanning is used in the literature to explain the increased identification of unsuspected intussusceptions.11 Liberal use of abdominal CT scans has also led to diagnosis of intussusception in patients without a lead point. The literature demonstrates that these patients are likely to have successful nonoperative management.10,11 As the resolution of CT scanning increases over time through evolution of multislice CT technology, we expect to see more idiopathic intussusceptions. Although we found similar sensitivity between single and multislice CT scans, the increased frequency of intussusceptions diagnosed at our institution over the study period may be explained by increased utilization of multislice technology. Although high-resolution CT technology will continue to identify more asymptomatic or idiopathic intussusceptions, it will help guide therapy and facilitate nonoperative management when appropriate.

This is a retrospective, single institution study with the associated limitations. It is possible that patients with intussusception at our institution were not captured. Additionally, 56 patients did not have CT scan specifications available. Although sensitivity of CT was determined, specificity and positive predictive value were not determined, as patients who were evaluated for possible intussusception but determined not to have the condition were not included. We were also unable to determine a false positive rate of CT, as it is unknown whether those diagnosed with intussusception on CT who go on to have spontaneous resolution were transient intussusceptions or actual false positives.

In conclusion, the diagnosis of intussusception in adults is increasing over time, particularly in those with idiopathic etiologies. This is associated with increased utilization of high-resolution CT technology, which facilitates the safe pursuit of nonoperative management in patients without concerning symptoms or evidence of a lead point on CT. Additional studies with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm the safety of conservative management.

Discussion

Dr Conor P. Delaney (Cleveland, OH): Can you clarify how you defined your patients? Specifically, did your database search discharge codes or inpatient EMR text and radiology reports or a combination? Second, the specificity for CT is generally about 50 to 70%, while the malignancy rate for those undergoing surgery is 40%. Knowing these facts, did any of the conservatively treated patients present later on with malignancy or other complications? And do you have data or recommendations for follow-up of conservatively treated patients? Third, 80% of patients were diagnosed since 1995, and yet laparoscopy was only used for about a third of the patients undergoing surgery. Can you explain why this might be so or whether this was explained by a high conversion rate because of obstructive patients? And, finally, were there any false positive patients through CT who underwent surgery and were found not to have an intussusception?

Dr Polites: For the first question, we identified patients using a database that we have at Mayo that’s been in place since the beginning of the study period. We searched both by ICD-9 code, which there is only one code for intussusception, and also by Free-text code and these were on the discharge abstract diagnosis list, and this database has been validated in the literature as accurate for both ICD-9 and Free-text searching. That being said, I’m sure we missed a few patients, which is, unfortunately, a problem with any retrospective study.

Unfortunately, we only had 30-day follow-up in this study, so certainly even though an intussusception would be transient that doesn’t mean that it didn’t have necessarily a lead point, so for managing every transient or incidentally identified intussusception non-operatively, we are missing the opportunity to definitively identify if there is a lead point there or not. CT is accurate for identifying lesions in the small bowel but not perfect. Ideally in our study, we would like to be able to determine specificity and positive and negative predictive value of CT for identifying these lesions, but we don’t have the denominator to do that. Your third question about utilization of laparoscopy, these procedures are generally done by our emergency general surgeons often in the middle of the night and the weekend, so especially in the ’90s and early 2000’s, laparoscopy was not utilized as much as it is starting to be now in this setting. The false positives, so these patients would be CT evidence of intussusception and then you don’t find anything on operative exploration. We believe that these would actually be the transient intussusception. There is no way to know whether it was just a false positive on the CT scan versus an intussusception that was reduced on its own.

Dr James Madura (Phoenix, AZ): In your resected patients, did you review the pathology? Did I miss that in your presentation? What did you find? Was it just intussuscepted intestine, or were these lipomas and intraluminal lesions?

Dr Polites: The most common was benign tumors or benign lead points, so things like lipomas and that, that was 21%; 19% were malignant lead points, and then after that it was inflammatory diseases, celiac disease. And then we also had eight patients where the only possible explanation was that they did have a previous gastric bypass in the Roux limb.

Dr William Cirocco (Columbus, OH): I suspect the ileocolonic or colo-colonic would have a much higher rate of malignancy than 24% and maybe we could say the small bowel we could perhaps observe more safely than the colonic-involving tumors.

Dr Polites: A national database found that the chances of a malignancy are much higher with an intussusception affecting the colon.

Acknowledgments

There were no relevant financial relationships or any sources of support in the form of grants, equipment, or drugs.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM, editors. Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindor RA, Bellolio MF, Sadosty AT, et al. Adult intussusception: presentation, management, and outcomes of 148 patients. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onkendi EO, Grotz TE, Murray JA, et al. Adult intussusception in the last 25 years of modern imaging: is surgery still indicated? J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1699–705. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1609-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuppermann N, O’Dea T, Pinckney L, et al. Predictors of intussusception in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:250–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandeville K, Chien M, Willyerd FA, et al. Intussusception: clinical presentations and imaging characteristics. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:842–4. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318267a75e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azar T, Berger DL. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg. 1997;226:134–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199708000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundaram B, Miller CN, Cohan RH, et al. Can CT features be used to diagnose surgical adult bowel intussusceptions? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:471–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barussaud M, Regenet N, Briennon X, et al. Clinical spectrum and surgical approach of adult intussusceptions: a multicentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:834–9. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0789-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh B, Singh A, Ahmed A, et al. Derivation and validation of automated electronic search strategies to extract Charlson comorbidities from electronic medical records. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:817–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olasky J, Moazzez A, Barrera K, et al. In the era of routine use of CT scan for acute abdominal pain, should all adults with small bowel intussusception undergo surgery? Am Surg. 2009;75:958–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rea JD, Lockhart ME, Yarbrough DE, et al. Approach to management of intussusception in adults: a new paradigm in the computed tomography era. Am Surg. 2007;73:1098–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]