Abstract

Induction chemotherapy is likely to be effective for biologically distinct subgroups of cancer patients with biomarker detection. In order to investigate the prognostic and predictive values of cyclin D1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma(OSCC) who were treated in a prospective, randomized, phase 3 trial evaluating standard treatment with surgery and post-operative radiotherapy preceded or not by induction docetaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil(TPF). Immunohistochemical staining for cyclin D1 was performed in pretreatment biopsy specimens of 232 out of 256 clinical stage III/IVA OSCC patients randomized to the clinical trial. Cyclin D1 index was estimated as the proportion of tumor cells with cyclin D1 nuclear staining. A low cyclin D1 expression predicted significantly better overall survival(P=0.001), disease-free survival(P=0.005), locoregional recurrence-free survival(P=0.003) and distant metastasis-free survival(P=0.002) compared to high cyclin D1 expression. Cyclin D1 expression levels were not predictive of benefit from induction TPF in the population overall. However, patients with nodal stage cN2 whose tumors had high cyclin D1 expression treated with TPF had significantly greater overall survival(P=0.025) and distant metastasis-free survival(P=0.025) when compared to high cyclin D1 cN2 patients treated with surgery upfront. Patients with low cyclin D1 level or patients with cN0 or cN1 disease did not benefit from induction chemotherapy. This study indicates that cN2 OSCC patients with high cyclin D1 expression can benefit from the addition of TPF induction chemotherapy to standard treatment. Cyclin D1 expression could be used as a biomarker in further validation studies to select cN2 patients that could benefit from induction therapy.

Keywords: Cyclin D1, Oral squamous cell carcinoma, Induction chemotherapy, Predictive biomarker, Prognostic biomarker

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common malignant tumor in the oral and maxillofacial region, with about 300,000 new cases worldwide each year (1,2). Many efforts have been made to improve the diagnosis and treatment of OSCC patients; however, the prognosis is still poor with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 50–60% (3,4), with even poorer outcomes noted in those patients with local-regionally advanced disease. For patients with resectable locally advanced OSCC, the most commonly recommended treatment is radical surgery followed by post-operative radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy depending on the presence of high risk features in the surgical specimen.

Induction chemotherapy has been investigated as a possible strategy to shrink or downstage locally advanced head and neck cancers, increase organ preservation rates, and/or reduce the risk of locoregional and/or distant recurrence, ultimately improving treatment outcomes. Induction chemotherapy with a combination of docetaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (TPF) followed by radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy has been shown to improve overall survival (OS) compared to induction chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (PF) in two randomized phase 3 trials (TAX323 and TAX324) (5–7). As a result, TPF is suggested as the preferred combination chemotherapy regimen when induction treatment is used for non-surgical management of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients. Despite the potential benefits seen in these initial studies, the role of TPF induction chemotherapy for non-surgical management of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas has been questioned especially after presentation of the results of the recently completed DeCIDE and PARADIGM trials. These studies compared chemoradiotherapy upfront versus induction TPF followed by chemoradiotherapy, and failed to demonstrate a significant improvement in OS or disease-free survival (DFS) for patients receiving TPF (8,9).

To address the role of induction TPF in HNSCC treated with surgery (as opposed to the non-surgical approach utilized in the aforementioned studies), we recently conducted and presented the results of a randomized, phase 3 trial of induction TPF followed by surgical resection versus surgical resection upfront in patients with locally advanced OSCC (10). In concert with DeCIDE and PARADIGM, we were also unable to demonstrate a survival advantage for induction chemotherapy in the overall study population. Taken together, these data demonstrate that induction chemotherapy should not be universally integrated into non-surgical or surgical management of patients with OSCC. It is possible, however, that induction chemotherapy with TPF might improve outcomes in molecularly defined subgroups of patients, and correlative studies from the aforementioned randomized trials could assist in identifying candidate biomarkers predictive of benefit from induction treatment.

The cyclin D1 gene is a proto-oncogene located on chromosome 11q13, which encodes the cyclin D1 nuclear protein, a positive cell cycle regulator. Cyclin D1 binds and activates CDK4 and CDK6, forming a complex that catalyzes Rb protein phosphorylation resulting in the release of transcriptional regulators E2F from Rb. This promotes cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase (11). Although increased expression of cyclin D1 in OSCC has been reported, there are controversial data on the prognostic value of cyclin D1 overexpression in OSCC. Some studies suggest that increased expression of cyclin D1 is associated with poor survival (12–16), while other studies demonstrate that cyclin D1 overexpression provides little prognostic information for patients with OSCC (17,18).

The aim of this study is to evaluate cyclin D1 expression in the pretreatment biopsy samples from patients who had local-regionally advanced, resectable OSCC and had been enrolled in a randomized phase 3 trial of TPF induction chemotherapy followed by surgery and post-operative radiotherapy compared to upfront surgery and post-operative radiotherapy, and to examine its possible prognostic and predictive role in this patient population. We hypothesize that high levels of expression of cyclin D1 will be associated with shortened OS in patients treated with surgery upfront, but will be predictive of OS benefit from TPF induction chemotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This study was based on patients who were enrolled in a prospective, open label, randomized, phase 3 trial at the Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, which aimed to test the hypothesis that TPF induction chemotherapy administered prior to surgery and post-operative radiotherapy would improve survival over surgery upfront in patients with resectable locally advanced OSCC (trial registration ID: NCT01542931). Details of the clinical trial have been previously described (10). Briefly, main eligibility criteria included: resectable squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, clinical stage III or IVA (T1-2N1-2M0 or T3-4N0-2M0, UICC 2002), Karnofsky performance status >60%, and adequate hematologic, hepatic and renal function. Eligible patients were randomly allocated to the control arm (surgery followed by post-operative radiotherapy) or experimental arm (TPF induction chemotherapy followed by surgery and post-operative radiotherapy). TPF induction chemotherapy consisted of docetaxel 75mg/m2 intravenously on day 1, followed by cisplatin 75mg/m2 intravenously on day 1, followed by 5-fluorouracil 750mg/m2/day as a 120-hour continuous intravenous infusion on days 1 through 5, every 3 weeks for 2 cycles. Surgery was performed at least 2 weeks after completion of induction chemotherapy, and consisted of radical resection of the primary lesion and full neck dissection (functional or radical) with appropriate reconstruction (pedicle or free flap). Post-operative radiotherapy was initiated 4–6 weeks after surgery, at a dose of 1.8–2Gy/day, 5 days/week for 6 weeks, totally 54–60Gy; in patients with high risk features, such as positive surgical margins, extracapsular nodal spread, or vascular embolism, a total radiation dose of 66Gy was recommended.

The clinical tumor response was determined by clinical evaluation and imaging studies (performed at baseline and 2 weeks after cycle 2 of induction chemotherapy). Responses were characterized according to the RECIST version1.0 (19). The pathologic response to TPF induction chemotherapy was assessed by examination of at least 20 slides of the resected specimen. A favorable response was defined as absence of any tumor cells (pathologic complete response) or presence of scattered foci of a few tumor cells(minimal residual disease with <10% viable tumor cells), as previously described by Licitra et al (20).

After treatment, patients were monitored every three months in the first two years, every six months in the subsequent 3–5 years, and once a year thereafter until death or data censoring.

Detection of cyclin D1 expression using immunohistochemistry

Pretreatment formalin fixed and paraffin embedded biopsy samples were collected for detection of cyclin D1 expression; however, in the control arm, if pretreatment biopsy was unavailable, a portion of the surgical resection specimen was collected for biomarker evaluation. Sections 4μm thick were studied using both hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining (for diagnostic confirmation according to the WHO histological criteria (21)) and immunohistochemical staining for cyclinD1. Immunohistochemical staining was performed as previously described (22,23). In brief, after deparaffinization, endogenous peroxidase was blocked, and the sections were heated by water bath at 98°C with 0.01M citrate buffer solution (pH 6.0) for 20min to retrieve antigen, and cooled at room temperature, then washed with PBS 3 times for 5min each, then incubated with the rabbit monoclonal antibody to cyclin D1 (clone-EPR2241, Epitomics, Inc., USA) at 1:150 dilution overnight at 4°C. After recovering to room temperature for 1h, the sections were washed with PBS 3 times for 5min each. Staining was then visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) detection kit of Dako Real™ EnVision™ Detection System, Peroxidase/DAB+, Rabbit/Mouse (Dako Cytomation, Denmark). The 1:150 dilution was the most optimal when compared to 1:50, 1:100, and 1:200. A negative control was prepared using PBS instead of cyclin D1 antibody. Two pathologists blinded to the treatment groups scored the slides. Staining for cyclin D1 expression was observed in the cellular nucleus. The cyclin D1 expression index was determined based on the proportion of stained cells using a semi-quantitative scale: negative, ≤10% of stained cells; weak positive, <50% of stained cells; and strong positive, ≥50% of stained cells (Supplemental Figure S1). Low cyclin D1 expression was defined as negative and weak positive cyclin D1 expression, whereas high cyclin D1 expression was defined as strong positive cyclin D1 expression. This was based on previous studies demonstrating that the chosen cutoff of 50% was reasonable for prognostic analysis in OSCC (12,24).

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of randomization to the date of death; disease-free survival (DFS) /locoregional recurrence-free survival (LRFS) /distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) were calculated, respectively, from the date of randomization to recurrence/locoregional recurrence/distant metastasis or death from any cause.

For descriptive analysis, categorical data were expressed as number and percentage. The chi-square test was applied to compare the difference between the baseline factors and cyclin D1 expression. The survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model. The intention-to-treat principle was applied for efficacy analysis. All hypothesis-generating tests were two-sided at a significance level of 0.05. Data were analyzed with the statistical software SPSS13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., USA)

Results

Patient characteristics and treatment outcomes

From 03/2008 to 12/2010, 256 eligible patients were enrolled in this study (128 patients in each arm), and 232 (91%, 127 patients in the control arm, 105 patients in the experimental arm) patients were assessed for pretreatment cyclin D1 expression levels in the tumor. The distribution of baseline characteristics in the subset of patients that had biomarker evaluation was similar to the distribution in the entire trial population (Table 1). No patients were lost to follow-up. The median follow-up time was 30 months among the censored patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and Cyclin D1 expression

| Characteristics | Total patients N=256 | Cyclin D1 expression

|

P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low N=155 | High N=77 | |||

|

| ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 179 (69.9) | 103 (66.5) | 57 (74.0) | 0.240 |

| Female | 77 (30.1) | 52 (33.5) | 20 (26.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| <60 | 168 (65.6) | 105 (67.7) | 52 (67.5) | 0.974 |

| ≥60 | 88 (34.4) | 50 (32.3) | 25 (32.5) | |

|

| ||||

| Site | ||||

| Tongue | 113 (44.1) | 62 (40.0) | 36 (46.8) | 0.366 |

| Buccal | 45 (17.6) | 31 (20.0) | 12 (15.6) | |

| Gingiva | 40 (15.6) | 28 (18.1) | 10 (13.0) | |

| Floor of mouth | 30 (11.7) | 18 (11.6) | 11 (14.3) | |

| Palate | 18 (7.0) | 10 (6.5) | 4 (5.2) | |

| Retromolar trigone | 10 (3.9) | 4 (2.6) | 6 (7.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Clinical T descriptor | ||||

| T1/T2 | 66 (25.8) | 42 (27.1) | 19 (24.7) | 0.693 |

| T3/T4 | 190 (74.2) | 113 (72.9) | 58 (75.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Clinical N descriptor | ||||

| N0 | 110 (43.0) | 65 (41.9) | 34 (44.2) | 0.905 |

| N1 | 94 (36.7) | 59 (38.1) | 27 (35.1) | |

| N2 | 52 (20.3) | 31 (20.0) | 16 (20.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Clinical stage | ||||

| III | 177 (69.1) | 109 (70.3) | 51 (66.2) | 0.526 |

| IVA | 79 (30.9) | 46 (29.7) | 26 (33.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Pathologic differentiation | ||||

| Well | 80 (31.2) | 49 (31.6) | 16 (20.8) | 0.178 |

| Moderately | 165 (64.5) | 98 (63.2) | 58 (75.3) | |

| Poorly | 11 (4.3) | 8 (5.2) | 3 (3.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Smoking status** | ||||

| Current/former | 126 (49.2) | 69 (44.5) | 41 (53.2) | 0.210 |

| Never | 130 (50.8) | 86 (55.5) | 36 (46.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Alcohol use*** | ||||

| Positive | 98 (40.6) | 54 (34.8) | 34 (44.2) | 0.168 |

| Negative | 158 (59.4) | 101 (65.2) | 43 (55.8) | |

P value from the chi-square test was reported to compare the difference between low and high cyclin D1 expression based on the different baseline factors.

Former/current smokers defined as at least a one pack-year history of smoking.

Positive alcohol use was defined as current alcohol use of more than one drink per day for 1 year (12 ounces of beer with 5% alcohol, or 5 ounces of wine with 12%–15% alcohol, or one ounce of liquor with 45%–60% alcohol). All other patients were classified as negative alcohol use.

As previously described, no significant differences in OS, DFS, LRFS, or DMFS could be identified between the experimental and control arms in the entire patient population10. On exploratory analysis, cN2 patients benefited from TPF induction chemotherapy as regards to OS and DMFS10. The same analysis was performed in the 232 patients who had baseline cyclin D1 levels evaluated (Supplemental Figure S2). In this subset, OS at 2 years for the control and experimental arms was 68.8% and 72.6%, respectively (P=0.472). Disease-free survival at 2 years was 64.5% and 66.0%, respectively (P=0.592). The locoregional recurrence rate and distant metastasis rate in the control arm were 30.5% and 8.7%, respectively; in the experimental arm, the locoregional recurrence rate and distant metastasis rate were 31.3% and 5.5%, respectively. As observed for the entire trial population, cN2 patients benefited from TPF induction chemotherapy as regards to OS and DMFS (Supplemental Table S1).

Cyclin D1 expression and baseline characteristics

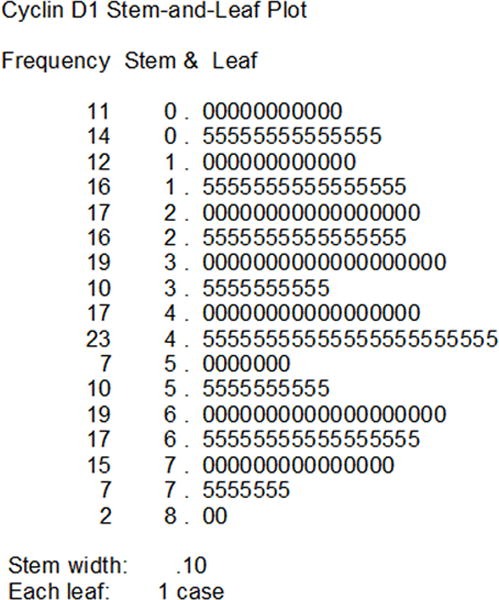

Figure 1 shows the relative frequency distribution of cyclin D1 expression index in this study. A total of 155 samples (84 in the control arm and 71 in the experimental arm) were found to have low cyclin D1 expression, including 37 negative (19 in the control arm and 18 in the experimental arm) and 118 weak positive (65 in the control arm and 53 in the experimental arm). There were 77 samples (43 in the control arm and 34 in the experimental arm) with high cyclin D1 expression. The distribution pattern of cyclin D1 expression was balanced between the two arms (Chi-square test=0.215, P=0.898). There were no significant differences in cyclin D1 expression according to gender, age, primary tumor site, stage, grade, tobacco or alcohol use (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Relative frequency distribution of cyclin D1 expression index in the 232 patients with resectable locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Cyclin D1 expression and patients’ outcomes

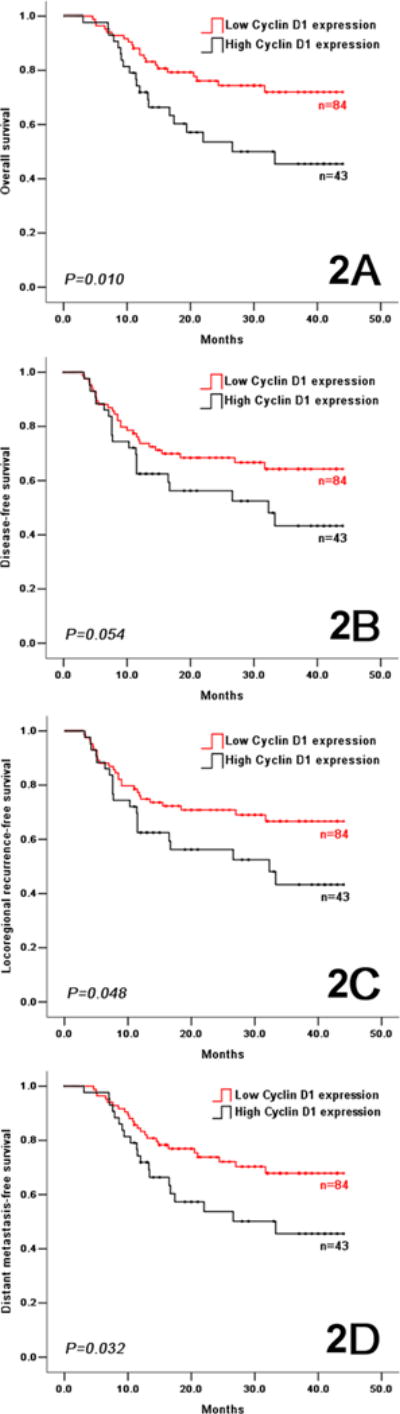

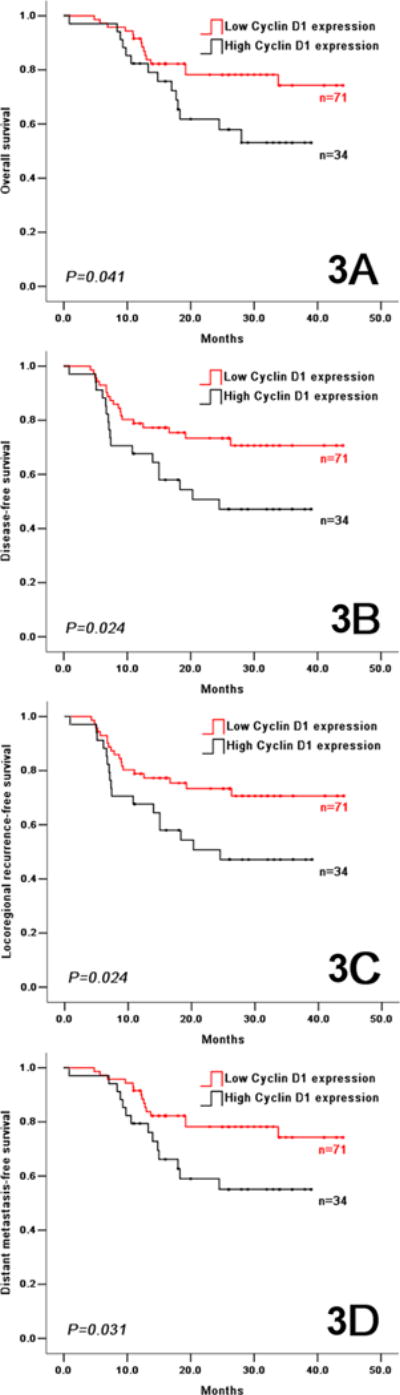

In the control arm, a low cyclin D1 expression predicted better outcomes with regard to OS, DFS, LRFS and DMFS (Figure 2). OS at 2 years was 76.3% and 53.7% in patients with low and high cyclin D1 expression, respectively (HR=0.453, 95% CI 0.245–0.838, P=0.012). DFS at 2 years was 68.7% and 56.5% in patients with low and high cyclin D1 expression, respectively (HR=0.571, 95% CI 0.321–1.006, P=0.053). The locoregional recurrence rate was 25.2% and 40.3% in the patients with low and high cyclin D1 expression, respectively; the distant metastasis rate was 5.2% and 9.1% in the patients with low and high cyclin D1 expression, respectively. The same association between high cyclin D1 expression levels and poor treatment outcomes (including OS, DFS, LRFS, and DMFS) were observed in patients treated with induction TPF (Figure 3), and in patients when putting the two arms together (Supplemental Figure S3). Exploratory subgroup analysis was performed on the cyclin D1 expression according to the baseline characteristics (Supplemental Figure S4). Female patients with low cyclin D1 expression had better outcomes, similar results were seen in elderly patients, patients with tongue cancer, patients with large tumor size, patients at clinical stage III, patients with moderately/poor differentiation grade, non-smokers, and non-drinkers.

Figure 2.

In the control arm, overall survival (2A), disease-free survival (2B), locoregional recurrence-free survival (2C), and distant metastasis-free survival (2D) in OSCC patients with low and high cyclin D1 expression.

Figure 3.

In the experimental arm, overall survival (3A), disease-free survival (3B), locoregional recurrence-free survival (3C), and distant metastasis-free survival (3D) in OSCC patients with low and high cyclin D1 expression.

Univariate Cox model was used to analyze the impact of baseline characteristics and cyclin D1 expression on the time-to-event endpoints in the control and experimental arms, separately. Cyclin D1 expression (low vs. high), lymph node status (cN0-1 vs. cN2) and clinical stage (stage III vs. stage IVA) were identified as risk factors for OS, DFS, LRFS and DMFS in the control arm; cyclin D1 expression (low vs. high) and clinical stage (stage III vs. stage IVA) were identified as risk factors for prognosis in the experimental arm (Supplemental Table S2). A multivariate Cox model analysis was performed including cyclin D1 expression and lymph node status (clinical stage was not included because of the overlap between lymph node status and clinical stage) in the control arm, cyclin D1 expression and clinical stage in the experimental arm. Cyclin D1 expression was found to be an independent risk factor for prognosis (Supplemental Table S3). Taken together, these data demonstrate that high level of expression of cyclin D1 is a poor prognostic biomarker in patients with OSCC.

Cyclin D1 expression and response to induction chemotherapy

In the experimental arm, the responses by RECIST in 105 patients with assessment of cyclin D1 that initiated induction chemotherapy were: 78.1% clinical response (4 patients with complete response and 78 patients with partial response) and 18.1% clinical non-response (18 patients with stable disease and 1 patient with disease progression), 4 patients were unevaluable for response. Favorable and unfavorable pathologic responses were observed in 26.7% (27/101) and 73.3% (74/101) of patients, respectively. Pathologic response could not be evaluated in 4 patients. Cyclin D1 expression did not correlate with clinical response to TPF induction chemotherapy (Chi-square test=2.297, P=0.130), or pathologic response to induction chemotherapy (Chi-square test=0.763, P=0.382) (Supplemental Table S4).

Cyclin D1 expression, treatment, and survival outcomes

To assess whether cyclin D1 expression could serve as a predictive biomarker of benefit from induction chemotherapy, we analyzed the interaction between the biomarker, treatment and survival outcomes. There were no significant differences in outcome between the experimental and control arms in patients with low cyclin D1 expression or in patients with high cyclin D1 expression (Table 2).

Table 2.

Survival comparison between the patients treated with and without TPF induction chemotherapy according to cyclin D1 expression

| Characteristics | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with low cyclin D1 expression | |||

| Overall survival | 0.857 | 0.442–1.663 | 0.649 |

| Disease-free survival | 0.797 | 0.445–1.427 | 0.445 |

| Locoregional recurrence-free survival | 0.863 | 0.477–1.559 | 0.625 |

| Distant metastasis-free survival | 0.736 | 0.386–1.403 | 0.351 |

|

| |||

| Patients with high cyclin D1 expression | |||

| Overall survival | 0.798 | 0.403–1.581 | 0.517 |

| Disease-free survival | 1.046 | 0.551–1.984 | 0.891 |

| Locoregional recurrence-free survival | 1.046 | 0.551–1.984 | 0.891 |

| Distant metastasis-free survival | 0.829 | 0.418–1.641 | 0.590 |

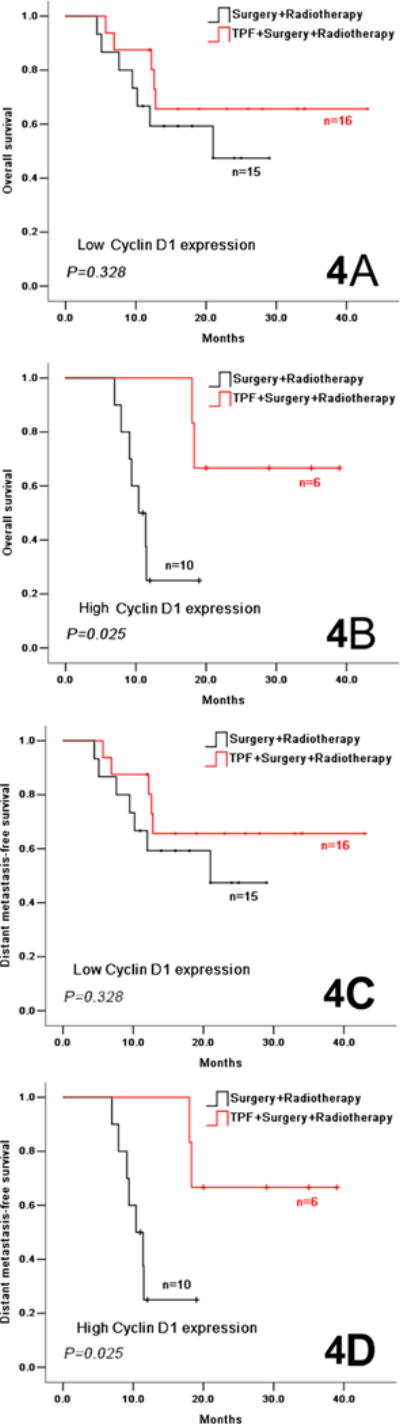

As previously described, both high cyclin D1 expression and cN2 were found to be associated with a higher risk for distant metastasis and reduced OS. We also demonstrated that TPF improves OS and DMFS in the cN2 subgroup. To assess whether cyclin D1 expression could serve as a predictive biomarker of benefit from TPF in a subset of patients at high risk for distant metastases and death, we performed an exploratory analysis of the interaction between cyclin D1, cN2 and survival outcomes. cN2 patients with high cyclin D1 expression benefited from TPF induction chemotherapy with respect to OS (HR=5.888, 95% CI 1.097–31.613, P=0.025) and DMFS (HR=5.888, 95% CI 1.097–31.613, P=0.025), while the cN2 patients with low cyclin D1 expression did not benefit from TPF induction chemotherapy (Figure 4, Supplemental Table S5). In contrast, the cN0 and cN1 patients, with either low or high cyclin D1 expression, did not benefit from TPF induction chemotherapy with regard to OS, DFS, LRFS and DMFS (Supplemental Table S5). There was no clear benefit from induction chemotherapy in any other subgroups (data not shown). Taken together, these exploratory analyses suggest that high expression level of cyclin D1 could serve as a predictive biomarker of benefit from induction chemotherapy in OSCC patients with cN2 disease.

Figure 4.

Overall survival (4A, 4B) and distant metastasis-free survival (4C, 4D) in cN2 OSCC patients in the experimental and control arms according to the low cyclin D1 expression (4A, 4C) and high cyclin D1expression (4B, 4D).

Discussion

In this study, we found that lower cyclin D1 expression in the pretreatment biopsy samples was a favorable prognostic biomarker, as it was associated with better OS, DFS, LRFS and DMFS in patients with resectable locally advanced OSCC treated in a prospective, randomized, phase 3 trial. Cyclin D1 expression was not a predictive biomarker of benefit from induction TPF in the population overall. However, on exploratory analysis, patients with cN2 nodal staging and high cyclin D1 expression benefited from TPF induction chemotherapy in terms of OS and DMFS; while cN2 patients with low cyclin D1 expression did not derive benefit from induction treatment.

Cyclin D1 plays an important role in cell cycle regulation. It forms a complex with and functions as a regulatory subunit of CDK4/CDK6, whose activity is required for cell cycle G1/S transition through phosphorylation of the Rb protein (11). Therefore, cyclin D1 overexpression promotes cell growth as well as tumorigenesis. In OSCC, both cyclin D1 overexpression and cyclin D1 gene amplification have been reported to correlate with adverse patients’ outcomes. Nimeus et al. and Miyamoto et al. have reported the cyclin D1 gene amplification could be a more reliable biomarker of poor clinical outcomes than cyclin D1 overexpression (25,26); however, data from Kaminagakura et al. suggest that cyclin D1 gene amplification may not be useful for predicting the patients’ outcomes (15). Potential explanations for this observation include the fact that cyclin D1 protein expression can be up-regulated by mechanisms other than gene amplification, such as increased transcription and impaired protein degradation (27–29). In addition, cyclin D1 protein levels can be increased by a post-transcriptional mechanism of Ras-dependent or Stat3-dependent induction (30,31). As such, we opted to evaluate cyclin D1 protein expression as a potential prognostic and predictive biomarker in this study. To our knowledge, this is the first time that cyclin D1 is assessed in a cohort of patients prospectively followed within the context of a randomized induction chemotherapy trial.

We found that lower or absent cyclin D1 expression is independently associated with better outcome in univariate and multivariate analyses, findings that are in accordance with results from previous retrospective studies (12–16). Patients with low cyclin D1 expression also had a relatively lower tumor locoregional recurrence rate and distant metastasis rate after treatment compared to the patients with high cyclin D1 expression.

Cyclin D1 was found to have limited utility as a predictive biomarker of clinical or pathologic response to TPF induction chemotherapy when we looked at the entire cohort of patients that received neoadjuvant treatment. However, an exploratory subgroup analysis showed that cN2 patients with high cyclin D1 expression had higher DMFS when treated with TPF, which translated to an improvement in OS. While this requires further validation in other data sets, one could envision a personalized treatment scenario in which OSCC patients with cN2 disease with high cyclin D1 expression receive TPF induction chemotherapy prior to surgery while those patients with low cyclin D1 expression are treated with surgery upfront, in order to avoid the toxicity from chemotherapeutic agents and the delay of definitive treatment.

Meta-analyses on induction chemotherapy in HNSCC patients have reported that induction chemotherapy followed by locoregional treatment can significantly decrease 5-year distant metastasis rate (32,33). The DeCIDE trial (8) and the study by Licitra et al (20) also demonstrated that induction chemotherapy reduces the risk of distant failure in this setting. In our prospective clinical trial, induction TPF also reduced the risk of distant failure rate from 8.7% to 5.5%, although the difference was not statistically significant. As demonstrated by the correlative studies presented herein, integration of evaluation of biomarkers such as cyclin D1 into the overall work-up and treatment strategy of locally advanced HNSCC patients may allow for a more accurate identification of individuals that are at highest risk of distant recurrence and that may potentially benefit from addition of systemic therapy prior to definitive treatment.

A limitation of our study, however, includes the fact that only 47 cN2 patients were assessed for cyclin D1 expression in the pretreatment biopsy samples. As such, these results need to be considered exploratory and hypothesis generating, and clearly need to be confirmed in further clinical trials with larger sample sizes.

In addition to our findings related to cyclin D1 expression, other biomarkers have been evaluated as potential predictors of benefit from induction treatment by other groups: p53 gene mutations have been found to be strongly associated with lower response rates to PF induction chemotherapy (34,35); Beta-tubulin and Bcl-xl (36–38) have also been found to be prognostic and predictive biomarkers in HNSCC patients receiving induction TPF or PF. However, before being widely embraced, further clinical trials using cyclin D1 and other prognostic and/or predictive biomarkers are needed to validate their clinical utility, and to realize the goal of personalized treatment of HNSCC patients based on their biomarker blueprint.

In conclusion, our study suggests that cyclin D1 high expression level should be considered a prognostic biomarker of poor outcomes in patients with resectable locally advanced OSCC, and as a possible predictive biomarker of benefit from TPF induction chemotherapy in patients with cN2 disease. Based on these findings, we plan to launch a randomized study of induction TPF in patients with cN2 OSCC, prospectively embedding cyclin D1 expression as a predictive biomarker in the clinical trial design. This will hopefully contribute to the development of a personalized induction treatment strategy for HNSCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Han-bing Fu and Dr. Ting Gu for providing technical support, and Dr. Dong-xia Ye for administrative assistance.

Grant supports: This study was supported by research grant 2007BAI18B03 from National Key Technology R&D Program of China (Z.Y. Zhang); by research grants 30973344 and 81272979 from National Natural Science Foundation of China (L.P. Zhong); by research grant 10dz1951300 from Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (C.P. Zhang), and by MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant: R21 NS091630.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interests

References

- 1.Kademani D. Oral cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:878–87. doi: 10.4065/82.7.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century-the approach of WHO Global Oral Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(suppl):3–23. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neville BW, Day TA. Oral cancer and precancerous lesions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:195–215. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.4.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Posner MR, Hershock DM, Blajman CR, Mickiewicz E, Winquist E, Gorbounova V, et al. Cisplatin and fluorouracil alone or with docetaxel in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1705–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vermorken BJ, Remenar E, Herpen VC, Gorlia T, Mesia R, Degardin M, et al. Cisplatin, fluorouracil, and docetaxel in unresectable head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1695–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorch JH, Goloubeva O, Haddad RI, Cullen K, Sarlis N, Tishler R, et al. Induction chemotherapy with cisplatin and fluorouracil alone or in combination with docetaxel in locally advanced squamous-cell cancer of the head and neck: long-term results of the TAX 324 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:153–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen EE. DeCIDE: A phase III randomzed trial of docetaxel(D), cisplatin(P), 5-fluorouracil(F)(TPF) induction chemotherapy(IC) in patients with N2/N3 locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck(SCCHN) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl):356s. abstr5500. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haddad RI. The RARADIGM trial: A phase III study comparing sequential therapy(ST) to concurrent chemoradiotherapy(CRT) in locally advanced head and neck cancer(LAHNC) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl):356s. abstr5501. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong LP, Zhang CP, Ren GX, Guo W, William WN, Jr, Sun J, et al. A randomized phase III trial of induction chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil followed by surgery versus surgery upfront in locally advanced and resectable oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.8820. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pestell RG, Albanese C, Reutens AT, Segall JE, Lee RJ, Arnold A. The cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in hormonal regulation of proliferation and differentiation. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:501–34. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.4.0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bova RJ, Quinn DI, Nankervis JS, Cole IE, Sheridan BF, Jensen MJ, et al. Cyclin D1 and p16INK4A expression predict reduced survival in carcinoma of the anterior tongue. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2810–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlos de Vicente J, Herrero-Zapatero A, Fresno MF, Lopez-Arranz JS. Expression of cyclin D1 and Ki-67 in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: clinicopathological and prognostic significance. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:301–8. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng Z, Guo W, Zhang C, Xu Q, Zhang P, Sun J, et al. CCND1 as a predictive biomarker of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaminagakura E, Werneck da Cunha I, Soares FA, Nishimoto IN, Kowalski LP. CCND1 amplification and protein overexpression in oral squamous cell carcinoma of young patients. Head Neck. 2011;33:1413–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.21618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang SF, Cheng SD, Chuang WY, Chen IH, Liao CT, Wang HM, et al. Cyclin D1 overexpression and poor clinical outcomes in Taiwanese oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:40. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah NG, Trivedi TI, Tankshali RA, Goswami JV, Jetly DH, Shukla SN, et al. Prognostic significance of molecular markers in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a multivariate analysis. Head Neck. 2009;31:1544–56. doi: 10.1002/hed.21126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perisanidis C, Perisanidis B, Wrba F, Brandstetter A, El Gazzar S, Papadogeorgakis N, et al. Evaluation of immunohistochemical expression of p53, p21, p27, cyclin D1, and Ki67 in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:40–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Licitra L, Grandi C, Guzzo M, Mariani L, Lo Vullo S, Valvo F, et al. Primary chemotherapy in resectable oral cavity squamous cell cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:327–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours; pp. 168–75. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong LP, Li J, Zhang CP, Zhu HG, Sun J, Zhang ZY. Expression of E-cadherin in cervical lymph nodes from primary oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:740–7. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong LP, Wei KJ, Yang X, Pan HY, Ye DX, Wang LZ, et al. Overexpression of Galectin-1 is positively correlated with pathologic differentiation grade in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:1527–35. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0810-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mineta H, Miura K, Takebayashi S, Ueda Y, Misawa K, Harada H, et al. Cyclin D1 overexpression correlates with poor prognosis in patients with tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:194–8. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(99)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nimeus E, Baldetorp B, Bendahl PO, Rennstam K, Wennerberg J, Akervall J, et al. Amplification of the cyclin D1 gene is associated with tumour subsite, DNA non-diploidy and high S-phase fraction in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:624–9. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyamoto R, Uzawa N, Nagaoka S, Hirata Y, Amagasa T. Prognostic significance of cyclin D1 amplification and overexpression in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:610–8. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang M, Spitz MR, Gu J, Lee JJ, Lin J, Lippman SM, et al. Cyclin D1 gene polymorphism as a risk factor for oral premalignant lesions. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:2034–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akervall JA, Michalides RJ, Mineta H, Balm A, Borg A, Dictor MR, et al. Amplification of cyclin D1 in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and the prognostic value of chromosomal abnormalities and cyclin D1 overexpression. Cancer. 1997;79:380–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akervall J, Borg A, Dictor M, Jin C, Jin Y, Tanner M, et al. Chromosomal translocations involving 11q13 contribute to cyclin D1 overexpression in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Oncol. 2002;20:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo Y, Stacey DW, Hitomi M. Post-transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1 expression during G2 phase. Oncogene. 2002;21:7545–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinibaldi D, Wharton W, Turkson J, Bowman T, Pledger WJ, Jove R. Induction of p21WAF1/CIP1 and cyclin D1 expression by the Src oncoprotein in mouse fibroblasts: role of activated STAT3 signaling. Oncogene. 2000;19:5419–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma J, Liu Y, Huang XL, Zhang ZY, Myers JN, Neskey DM, et al. Induction chemotherapy decreases the rate of distant metastasis in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma but does not improve survival or locoregional control: a meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:1076–84. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pignon JP, le Maître A, Maillard E, Bourhis J, MACH-NC Collaborative Group Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Temam S, Flahault A, Perie S, Monceaux G, Coulet F, Callard P, et al. p53 Gene status as a predictor of tumor response to induction chemotherapy of patients with locoregioally advanced squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:385–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perrone F, Bossi P, Cortelazzi B, Locati L, Quattrone P, Pierotti MA, et al. TP53 mutations and pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant cisplatin and fluorouracil chemotherapy in resected oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:761–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Y, Posner MR, Schumaker LM, Nikitakis N, Goloubeva O, Tan M, et al. Novel biomarker panel predicts prognosis in human papillomavirus-negative oropharyngeal cancer: an analysis of the TAX 324 trial. Cancer. 2012;118:1811–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar B, Cordell KG, Lee JS, Worden FP, Prince ME, Tran HH, et al. EGFR, p16, HPV Titer, Bcl-xL and p53, sex, and smoking as indicators of response to therapy and survival in oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3128–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cullen KJ, Schumaker L, Nikitakis N, Goloubeva O, Tan M, Sarlis NJ, et al. beta-Tubulin-II expression strongly predicts outcome in patients receiving induction chemotherapy for locally advanced squamous carcinoma of the head and neck: a companion analysis of the TAX 324 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6222–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.