Abstract

Objective

To compare between two of the largest U.S. clinical practice research datasets the risks of histologic high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or worse after different cervical cancer screening test results.

Methods

The New Mexico Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Pap Registry is a statewide registry representing a diverse population experiencing varied clinical practice delivery. Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is a large integrated health care delivery system practicing routine HPV cotesting since 2003. In this retrospective cohort study, a logistic-Weibull survival model was used to estimate and compare the cumulative 3- and 5-year risks of histologic cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse (CIN3+) among women age 21–64 screened in 2007–2011 in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and 2003–2013 in KPNC. Results were stratified by age and baseline screening result: negative cytology, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) (with or without HPV triage), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL).

Results

There were 453,618 women in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and 1,307,528 women at KPNC. The 5-year CIN3+ risks were similar within screening results across populations: cytology negative (0.52% and 0.30%, respectively p=<.001), HPV-negative and ASC-US (0.72% and 0.49%, respectively, p=.5), ASC-US (3.4% and 3.4%, respectively, p=.8), HPV-positive and ASC-US (7.7% and 7.1%, respectively, p=.3), LSIL (6.5% and 5.4%, respectively, p=.009), and HSIL (53.1% and 50.4%, respectively, p=.2). CIN2+ risks and 3-year risks had similar trends across populations. Age-stratified analyses showed more variability, especially among women age <30, but patterns of risk stratification were comparable.

Conclusion

Current U.S. cervical screening and management recommendations are based on comparative risks of histologic high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia after screening test results. The similar results from these two large cohorts from different real-life clinical practice settings support risk-based management thresholds across US clinical populations and practice settings.

Précis

Results from two large cohorts from different clinical settings support risk-based management thresholds for cervical screening across U.S. clinical populations and practice settings.

Introduction

U.S. practice guidelines for cervical cancer screening and management are becoming increasingly complex, as new tests become available (1–5). The latest cervical screening and management guidelines evaluate tests and determine appropriate management strategies by comparing the risk of precancer or cancer after each test result to a threshold risk that defines management (1, 2). For example, colposcopy referral is recommended when the risk after a given screening or histology result is similar to or greater than the risk associated with a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) cytology result. Similarly, a return to routine screening is considered safe when the risk after a given test result is similar to or less than the risk associated with negative cervical cytology.

The current guidelines were based in large part on one source of data, namely, women undergoing cervical screening at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), a large integrated health delivery system that has practiced routine cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) cotesting since 2003. Yet, the KPNC practice setting does not necessarily reflect most parts of the U.S. medical system that include more diverse demographic characteristics, patient management and laboratory methods and quality (6–8); the generalizability of risk estimates could be questioned.

The New Mexico Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Pap Registry provides a valuable comparison to KPNC. The longitudinal data from the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry are derived from a heterogeneous population attending diverse health care settings. To investigate whether the risk estimates from KPNC that informed current guidelines are generalizable, we compared the risks of cervical cancer and precancer for cytology and HPV results at the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and KPNC. Similar risk relationships across the large contrasting settings would provide supporting evidence for current and potentially future guidelines.

Materials and Methods

Established in 2006 as a statewide public health surveillance activity, the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry encompasses the screening and diagnostic cervical cancer screening services for residents across the entire state of New Mexico (9, 10). The structure of the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry has been described previously (9). Under state regulation, laboratories must report to the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry all results of cervical cytology, cervical pathology and HPV tests as well as vulvar and vaginal pathology performed on New Mexico residents (10). Cervical cytology and HPV results are routinely ascertained from 9 laboratories in New Mexico and 9 out-of-state laboratories that serve New Mexico residents. All hospitals and clinical practices in New Mexico report through these laboratories. Probabilistic matching and linking of different tests to a particular woman are performed and augmented by manual reviews when linkage is uncertain. Ongoing evaluations of cervical screening, diagnosis, and treatment by the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry have been reviewed and approved under exempt status by the University of New Mexico Human Research Review Committee. The National Institutes of Health Office of Human Subjects Research has similarly deemed this study exempt from IRB review because does not contain personally identifiable information.

This analysis expands upon an earlier, separate analysis of the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry data and therefore presents some risk estimations previously published (11). Women age 21–64 were included if their baseline cytology result was negative, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) or high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) reported during January 1, 2007 (when complete data collection commenced) through December 31, 2011. This analysis excluded women with baseline cytology results of atypical glandular cells (AGC), atypical squamous cells cannot rule out high-grade (ASC-H) or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Baseline is defined as the first screening result reported for a woman on or after January 1, 2007. Women were excluded if records indicated that they had a prior cervical cytology within 300 days of their baseline screening cytology (suggesting that the baseline test was a follow-up rather than screening test) or if they had a prior cervical excisional procedure reported to the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (i.e., loop electrosurgical excisional procedure [LEEP] or cone biopsy) or hysterectomy, prior to their baseline screening cytology (9, 12). Women with abnormal baseline cytology and no subsequent follow-up were excluded from all analyses.

Women were followed through electronic and paper medical records submitted to the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (13). The outcomes were defined by local community readings of histopathology results from biopsy, endocervical curettage, excisional procedure or hysterectomy without central review, from the date of baseline screening through December 31, 2013. A histologic outcome of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 2 or worse (CIN2+) included results of CIN1-2, CIN2, CIN2-3, CIN3, CIS, adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), squamous-cell carcinoma or high-grade (not otherwise specified [NOS]). An outcome of CIN3+ was defined as a result of CIN2-3, CIN3, CIS, AIS, or squamous-cell carcinoma. Adenocarcinomas (n=154) were excluded from this report due to ongoing work related to potential misclassifications of cervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas. Follow-up for outcomes was terminated at the date of an excisional procedure, or hysterectomy.

Kaiser Permanente is a non-profit integrated health care system which, as part of its mission, researches health outcomes within its membership. Under a data sharing agreement with NCI, KPNC shared aggregate data, stripped of personal identifying information, from its electronic medical records on cervical cytology results, HPV test results, and histopathology diagnoses. The KPNC cohort consists of a longitudinal dataset of over 1 million women and is a large cohort, providing precise risk estimations. The KPNC cervical screening program and our methods for risk calculation have been described previously (14, 15). Women enrolled in KPNC represent a generally well-screened population whose medical services are managed according to guidelines established by the Kaiser Permanente Medical Group. Most cytology specimens are processed and read at the Regional Laboratory, which benefits from intensive quality control. All HPV testing (using HC2, Qiagen, Germantown, MD) is performed at that same laboratory.

Briefly, women age 30–64 undergoing HPV cotesting and women age 21–29 mainly undergoing cervical cytology testing with HPV triage of ASC-US, in the period of 2003-June 2013. Cotesting was performed on two separate co-collected specimens, with cervical cytology tests performed on the first of the two. Women were followed according to routine local practice: 1) Women with HPV-positive and ASC-US cytology, and LSIL or more severe results regardless of HPV status were referred to colposcopy; 2) HPV-negative and ASC-US cytology led to a recommendation of rescreening in one year; 3) women age 30–64 who tested both HPV and cervical cytology negative (cotest negative) were rescreened in 3 years; and women age 21–29 who tested cervical cytology negative were rescreened in 3 years.

For each woman age 21–64 years undergoing cervical cancer screening in the period of 2003–June 2013, we considered as the enrollment screen the first available cervical screening tests in the study period. Among women with an enrollment cervical cytology or HPV result, we excluded women with the following clinical history: previous excisional biopsy, hysterectomy or treatment, concurrent treatment or biopsy at the time of enrollment screen, previous diagnosis of CIN2+ or HSIL/ASC-H cytology, an immediately previous screening result that was HPV-positive or ASC-US or worse cytology, or a prior biopsy or cervical cytology test of any result within 300 days of enrollment screen (suggesting enrollment screen was a follow-up rather than screening test). Histologically confirmed cases of CIN2, CIN3 and cancer were ascertained from histopathology results of biopsies and excisional treatment through December 31, 2013.

Of note, cytology practice evolved at KPNC during the 12 years of HPV cotesting. Conventional cytology was replaced by SurePath (BD Diagnostics, Burlington, NC, USA), pre-review of slides by FocalPoint automated cytology readings was instituted, and beginning in 2007 HPV status was routinely revealed to cytologists.

The overall distribution of cytology screening results (normal, ASC-US, LSIL and HSIL cytology plus ASC-US and HPV-positive and ASC-US and HPV-negative for HPV triage of ASC-US) was compared between the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and KPNC. The age-stratified distribution of screening results was also compared between cohorts with age categorized as: 21–24, 25–29, 30–39, 40–49 and 50–64 years. The age ranges of 21–24 and 25–29 were chosen to show risks during ages for which there are different screening guidelines in the U.S. (i.e. primary HPV screening is now recommended among women age 25 and older while HPV testing from the start of screening at 21 to age 24 is not recommended due to high HPV prevalence and very rare cancer). The age-standardized distribution of screening results was calculated using the age distribution among females in the 2012 U.S. Census as a reference.

We calculated the cumulative incidence of histological outcomes of CIN2+ and CIN3+ for each age grouping, screening result (defined above) and age-stratified screening result using methods previously described (11, 14, 15). We concentrate on risk of CIN3+ while CIN2+, a less reproducible and severe diagnosis of precancer, is included for completeness. Using a logistic-Weibull model, we calculated the cumulative risk as the sum of risk at the baseline cervical cytology (plotted at time zero on each figure) and the incidence after baseline. Risk estimates were compared and p-values for statistical significance were calculated from 95% CI confidence intervals. This was a retrospective exploratory analysis. P-values are given as nominal values and no adjustment for multiple comparisons have been made. All analyses were conducted using SAS® software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Overall, 456,519 and 1,313,128 women in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and KPNC cohorts, respectively, had a baseline cervical cytology screening result. The distribution of cytologic abnormalities varied slightly between the cohorts with a slightly greater proportion of non-normal cytology results in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (7.19%) vs. KPNC (6.14%, p<.001) (Table 1). Among women with an ASC-US cervical cytology and concurrent HPV test for triage, HPV-positivity was lower in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry compared with KPNC (41.0% of 15,724 women vs. 49.2% of 51,527 women, p<.001).

Table 1.

The distribution of cytology results among women age 21–64 in 1) the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (NMHPVPR) and 2) Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) cohorts

| NMHPVPR | KPNC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| HSIL | 1,573 | 0.34% | 2,771 | 0.21% |

| Other high grade non-normal result* | 2,901 | 0.64% | 5,600 | 0.43% |

| LSIL | 8,211 | 1.80% | 19,096 | 1.45% |

| ASC-US | 20,117 | 4.41% | 53,107 | 4.04% |

| HPV-positive/ ASC-US | 6,451 | 41.0% | 25,336 | 49.2% |

| HPV-negative/ ASC-US | 9,273 | 59.0% | 26,191 | 50.8% |

| HPV-unknown/ ASC-US | 4,393 | - | 1,580 | - |

| Negative | 423,717 | 92.81% | 1,232,554 | 93.86% |

| TOTAL | 456,519 | 100.0% | 1,313,128 | 100.0% |

All women with an AGC, ASC-H or SCC Pap.

NMHPVPR is a state-wide registry capturing all cervical cytology and HPV tests and all cervical pathology under the New Mexico Notifiable Diseases and Conditions. Women were screened between 2007–2011.

KPNC is an integrated health care management system. Women were screened between 2003–June 2013.

The ratio of ASC-US vs. LSIL was 2.45 in NMHPV and 2.79 in KPNC.

LSIL: Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HPV: human papillomavirus, ASC-US: atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance, AGC: Atypical glandular cells, ASC-H: atypical squamous cells cannot rule out high-grade, HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, SCC: squamous cell carcinoma.

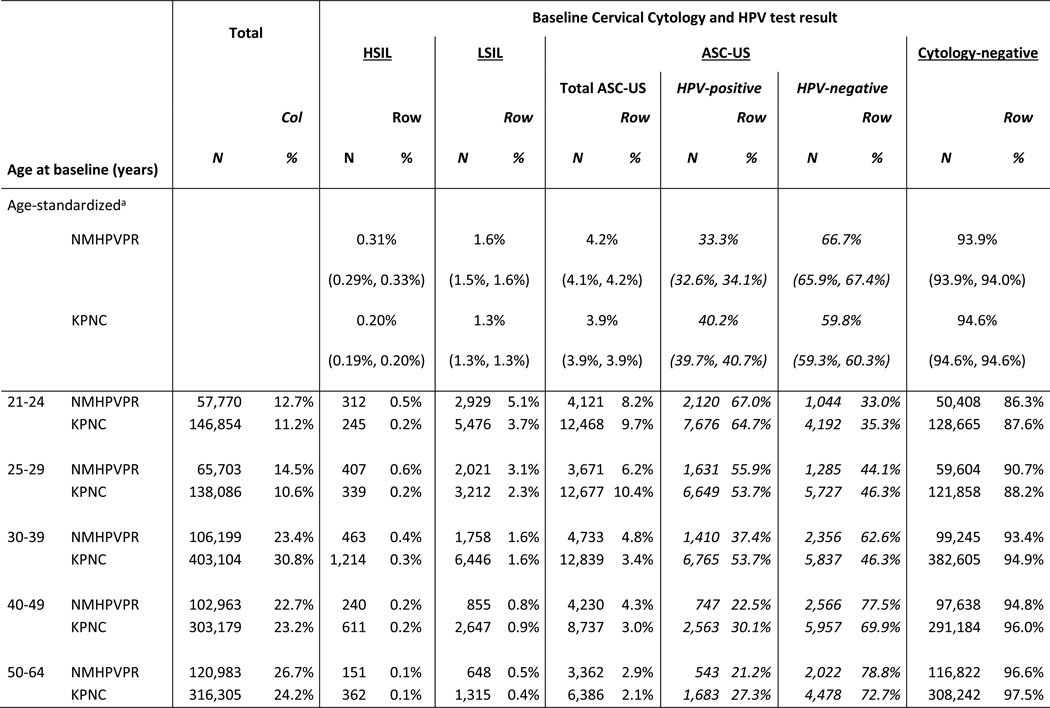

Women in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry were younger than women in KPNC (14.5% vs. 10.6% were age 25–29, left column in Table 2, p<.001). Within some age groups, the distribution of abnormal baseline screening results varied between cohorts. Women aged 21–24 years in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry were more likely to have an abnormal baseline screening cytology results compared with women of a similar age in KPNC (HSIL: 0.5% vs. 0.2%, respectively, p<.001; LSIL: 5.1% vs. 3.7%, respectively, p<.001). Women aged 25–29 years in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry were also more likely to have an abnormal baseline screening cytology results compared with women of a similar age in KPNC (HSIL: 0.6% vs. 0.2%, respectively, p<.001; LSIL: 3.1% vs. 2.3%, respectively, p<.001).

Table 2.

Distribution of cytology results by age among women age 21–64 in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and Kaiser Permanente Northern California cohorts with a Pap negative, ASC-US, LSIL or HSIL Pap test

NMHPVPR, New Mexico HPV Pap Registry; KPNC, Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

Standardized to the female population in 2012 US Census. 95% confidence intervals are shown in parenthesis below percent.

Women with baseline Pap results of AGC, ASC-H or SCC Pap are not presented.

NMHPVPR is a state-wide registry capturing all cervical cytology and HPV tests and all cervical pathology under the New Mexico Notifiable Diseases and Conditions. Women were screened between 2007-2011.

KPNC is an integrated health care management system Women were screened between 2003-June 2013.

LSIL: Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HPV: human papillomavirus, ASC-US: atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance, AGC: atypical glandular cells, ASC-H: atypical squamous cells cannot rule out high-grade, HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, SCC: squamous cell carcinoma.

The overall cumulative 3- and 5-year risks of CIN2+ and CIN3+, regardless of baseline screening result, are presented in Table 3 with risks stratified by age. The numbers of cases are presented in Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx. Overall risks in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry cohort were slightly higher compared with KPNC (5-year CIN3+: 0.88% vs. 0.59%, respectively, p<.001). The age-stratified findings showed that the primary difference in risks was observed among women age 21–24 years and 25–29 years in which women in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry had a higher 5-year risk of CIN3+ compared with women in KPNC (age 21–24 years: 2.0% vs. 0.69%, respectively, p<.001 and age 25–29 years: 1.7% vs. 1.2%, respectively, p<.001).

Table 3.

The age-stratified 3 and 5-year cumulative risks of CIN2+ and CIN3+ among women with negative, ASC-US, LSIL or HSIL Pap in 1) the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (NMHPVPR) and 2) Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) cohorts

| Cumulative 3 and 5-year risks of

CIN2+ (95% confidence intervals) |

Cumulative 3 and 5-year risks of

CIN3+ (95% confidence intervals) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline (years) | NMHPVPR | KPNC | p-value | NMHPVPR | KPNC | p-value | |

| Overall age 21–64 | (3-year risk) | 1.39 (1.36–1.43) | 1.12 (1.10–1.14) | <.0001 | 0.61 (0.59–0.64) | 0.44 (0.42–0.45) | <.0001 |

| (5-year risk) | 2.01 (1.95–2.06) | 1.52 (1.49–1.54) | <.0001 | 0.88 (0.85–0.92) | 0.59 (0.57–0.60) | <.0001 | |

| Overall age 21–29 | (3-year risk) | 3.00 (2.90–3.11) | 2.29 (2.22–2.37) | <.0001 | 1.23 (1.16–1.29) | 0.77 (0.73–0.82) | <.0001 |

| (5-year risk) | 4.35 (4.20–4.50) | 3.20 (3.08–3.32) | <.0001 | 1.83 (1.73–1.93) | 1.12 (1.05–1.19) | <.0001 | |

| Overall age 30–64 | (3-year risk) | 0.80 (0.77–0.83) | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | <.0001 | 0.39 (0.37–0.41) | 0.46 (0.44–0.47) | <.0001 |

| (5-year risk) | 1.15 (1.10–1.19) | 1.40 (1.37–1.43) | <.0001 | 0.54 (0.51–0.57) | 0.59 (0.57–0.61) | .007 | |

| Age 21–24 | (3-year risk) | 3.34 (3.19–3.50) | 1.67 (1.59–1.76) | <.0001 | 1.27 (1.17–1.37) | 0.48 (0.44–0.53) | <.0001 |

| (5-year risk) | 4.95 (4.72–5.19) | 2.34 (2.22–2.48) | <.0001 | 1.98 (1.83–2.14) | 0.69 (0.62–0.76) | <.0001 | |

| Age 25–29 | (3-year risk) | 2.71 (2.58–2.84) | 2.51 (2.34–2.70) | .092 | 1.19 (1.10–1.28) | 0.88 (0.78–0.99) | <.0001 |

| (5-year risk) | 3.83 (3.64–4.03) | 3.47 (3.23–3.73) | .028 | 1.70 (1.58–1.84) | 1.23 (1.09–1.39) | <.0001 | |

| Age 30–39 | (3-year risk) | 1.53 (1.45–1.61) | 1.54 (1.49–1.60) | .749 | 0.73 (0.68–0.79) | 0.64 (0.60–0.68) | .0058 |

| (5-year risk) | 2.17 (2.07–2.29) | 2.14 (2.07–2.21) | .559 | 1.01 (0.94–1.09) | 0.87 (0.83–0.92) | .0015 | |

| Age 40–49 | (3-year risk) | 0.64 (0.59–0.69) | 0.75 (0.71–0.79) | .0009 | 0.31 (0.28–0.35) | 0.32 (0.30–0.35) | .623 |

| (5-year risk) | 0.91 (0.84–0.99) | 1.03 (0.97–1.08) | .021 | 0.43 (0.38–0.48) | 0.43 (0.40–0.47) | .842 | |

| Age 50–64 | (3-year risk) | 0.28 (0.25–0.31) | 0.43 (0.40–0.46) | <.0001 | 0.15 (0.13–0.17) | 0.18 (0.16–0.20) | .038 |

| (5-year risk) | 0.41 (0.36–0.46) | 0.60 (0.56–0.64) | <.0001 | 0.21 (0.18–0.25) | 0.25 (0.22–0.28) | .132 | |

Women with baseline Pap results of AGC, ASC-H or SCC Pap are excluded from analysis.

NMHPVPR is a state-wide registry capturing all cervical cytology and HPV tests and all cervical pathology under the New Mexico Notifiable Diseases and Conditions. 453,618 women screened between 2007–2011 with a Pap negative, ASC-US, LSIL or HSIL Pap test were included.

KPNC is an integrated health care management system. 1,307,528 women screened between 2003–June 2013 with a Pap negative, ASC-US, LSIL or HSIL Pap test were included.

LSIL: Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HPV: human papillomavirus, ASC-US: atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance, AGC: Atypical glandular cells, ASC-H: atypical squamous cells cannot rule out high-grade, HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, SCC: squamous cell carcinoma.

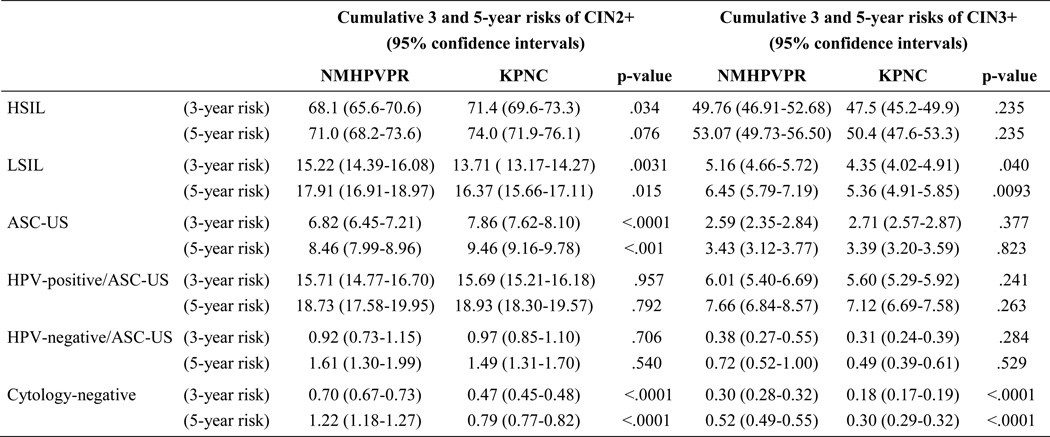

Table 4 stratifies the 3- and 5-year CIN2+ and CIN3+ risks by baseline screening result and compares risks between the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and KPNC. The numbers of cases are presented in Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx. For all screening results, the 5-year CIN3+ risk estimates were close between the two cohorts with small differences among women with LSIL cytology (6.5% vs. 5.4%, respectively, p=.009), HPV andnegative/ASC-US (0.72% vs. 0.49%, respectively, p=.5) and cytology-negative (0.52% vs. 0.30%, respectively, p<.001).

Table 4.

Cumulative risks of CIN2+ and CIN3+ in 3 and 5 years among women age 21–64 in 1) the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (NMHPVPR) and 2) Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) cohorts-stratified by screening result at enrollment.

NMHPVPR is a state-wide registry capturing all cervical cytology and HPV tests and all cervical pathology under the New Mexico Notifiable Diseases and Conditions. 453,618 women age 21-64 screened between 2007-2011 were included.

KPNC is an integrated health care management system. 1,307,528 women age 21-64 screened between 2003-June 2013 were included.

LSIL: Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HPV: human papillomavirus, ASC-US: atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance, AGC: Atypical glandular cells, ASC-H: atypical squamous cells cannot rule out high-grade, HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, SCC: squamous cell carcinoma.

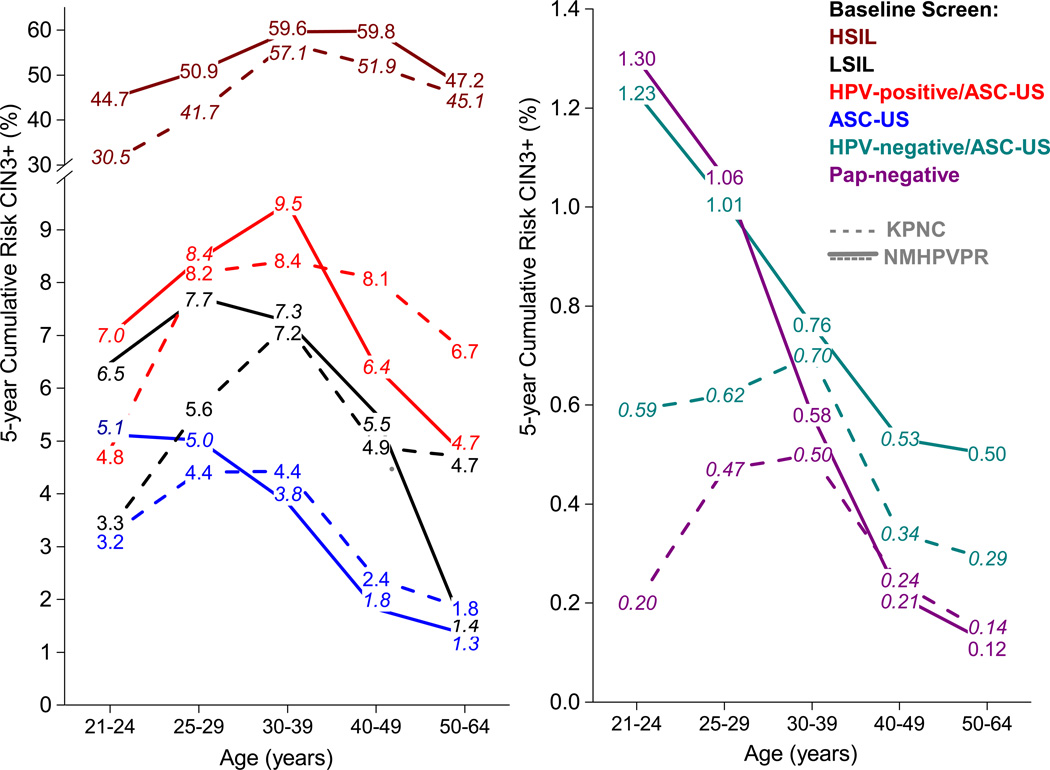

The 5-year risks of CIN3+ after baseline screening results stratified by age and referral cytology are presented in Figure 1 for the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (solid line) and KPNC (dotted line). The 5-year risks of CIN2+ are presented in Appendix 3, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx. Across all age groups, the 5-year CIN3+ risks showed a similar hierarchy for both cohorts: risks after an HSIL screening result were high (>30%), risks after an HPV-positive and ASC-US result were medium and similar to those after an LSIL cytology result, and risks after an HPV-negative and ASC-US result were low and close to those of a cytology-negative result. Across screening results, differences in risk were observed between the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and KPNC for certain age groups. Among women age 21–29 years, the 5-year CIN3+ risks in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry were higher than those in KPNC for almost all baseline screening results. Among women age 50–64 years, 5-year CIN3+ risks were lower in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry compared with KPNC after LSIL (1.4% vs. 4.7%, p=.007).

Figure 1.

Cumulative risks of CIN3+ by baseline age and screening result in 1) the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (NMHPVPR) and 2) Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) cohorts

In general, the risk relationships between cytology results and populations for 5-year CIN2+ risks were similar to 5-year CIN3+ risks and 3-year risks were similar to 5-year risks.

Discussion

The populations of the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and KPNC cohorts have slightly different immediate risks of cervical precancer (as estimated by the age-standardized prevalence of concurrent high-grade cytologic abnormalities at baseline screening) and risks of CIN2+ and CIN3+ histology within 3 and 5 years (slightly higher in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry compared to KPNC). In spite of these differences, the cumulative risks after each screening result were similar across most age groups and similarly stratified women into risk bands of high risk (HSIL), medium risk (LSIL, HPV-positive and ASC-US), low (ASC-US) and minimal risk (cytology-negative, HPV-negative and ASC-US).

HPV triage of ASC-US was useful as shown previously in studies worldwide (11, 16, 17). HPV positivity among women with ASC-US cytology results was lower in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry compared with KPNC. ASC-US was called slightly less often in KPNC, perhaps because the standardized cytology practices (including knowledge of HPV status) at the Kaiser laboratories may affect ASC-US proportions and HPV positivity.

Women in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry were younger and, compared with young women in KPNC, the young women in the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry had higher risks of cervical precancer. Notably, although risks differed, the overall risk stratification patterns for baseline screening results within both groups of younger women were similar. The reason for this higher risk of cervical precancer among younger women in New Mexico is unclear but has been observed in other studies (18). It is possible that among young women, the risk of HPV infection might be higher in New Mexico compared to KPNC although this difference was not observed among women with ASC-US screening results (12). We had no information on known etiologic cofactors such as smoking, multiparity, and hormonal contraceptive use.

Risks of precancer declined as women aged (11, 17, 19). Although these trends might reflect a true decline of risk as women accumulate years of cervical cancer screening, they could also be an artifact of declining sensitivity of screening or colposcopic biopsy to detect cervical precancer as women age (20, 21). Neither cohort has completely accounted for the prevalence of benign hysterectomy in the years after baseline screening.

Both the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and KPNC cohorts are from real-life clinical practices and are not a prospective study where women are systematically followed to ascertain disease status across standard multiple time points. Because women at KPNC had HPV cotesting, those testing cytology-negative and HPV-positive (3.7% of women testing cytology-negative) have repeat cotest in one year (16). Therefore, risk estimates for the first 3 years among women testing cytology-negative in KPNC could be slightly higher than would be observed in New Mexico where HPV cotesting was only used in 19.1% of women aged 30–65 years attending for screening in 2012 (although it has more than tripled from 2007 to 2012) (22).

Overall, the cumulative risks after each screening result were remarkably close between the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and KPNC, with the exception of the youngest and oldest ages. These differences in overall risks between the populations are likely explained by disparities in access to cervical cancer screening; approximately 29% of women age 21–65 years in New Mexico were not screened for cervical cancer between 2008–2011 compared with a much higher screening coverage in KPNC (9).

It was also assumed that risk estimates would vary by screening result between the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and KPNC because of the variability of clinical and laboratory practices. The New Mexico HPV Pap Registry represents a typical U.S. opportunistic screening scenario, with great diversity in health plans, clinical practice settings, and providers. By nature, the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry state-wide setting includes great variability in patient management, pathology and HPV laboratories with varying performance (23). KPNC is a large integrated healthcare delivery system that follows screening and management guidelines established by Kaiser Permanente Medical Group.

The risk estimates after screening results that are reported from the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry and KPNC cohorts are lower than those from other U.S. screening studies reporting higher CIN2+ and CIN3+ risks (24–26). This difference might be a result of study design as screening studies involve more rigorous follow-up including more frequent screening and colposcopy or the difference might represent different underlying risks within U.S. screening settings.

While absolute risk estimates for given screening results likely do not apply across all settings, the overall risk stratification patterns in other U.S. settings are consistent. Reassuringly, screening and treatment algorithms based upon cumulative risks of precancer or worse can apparently be applied across U.S. settings. Application to international settings with substantially different screening modalities and cervical cytology classification systems presents a greater challenge, although sometimes similar patterns might be observed (11).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by U54CA164336 (to CM Wheeler) from the US National Cancer Institute-funded Population-Based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) consortium and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services). The overall aim of PROSPR is to conduct multi-site, coordinated, transdisciplinary research to evaluate and improve cancer screening processes.

Dr. Wheeler has received funding through the University of New Mexico from Merck and Co., Inc. and Glaxo SmithKline for HPV vaccine studies and equipment and reagents from Roche Molecular Systems for HPV genotyping. Dr. Schiffman and Dr. Gage have received HPV testing for research at no cost from Roche and BD. Dr. Cuzick has received research funding and reagents from Qiagen, Roche, GenProbe/Hologic, Abbott, BD, Cepheid, Genera and Trovagene, and has been personally compensated for Advisory Boards or Speakers Bureau activities from Trovagene, GenProbe/Hologic, Abbott, BD, Merck and Cepheid. Dr. Castle has received HPV tests and testing for research at a reduced or no cost from Qiagen and Roche, has been compensated for serving as a member on a Data and Safety Monitoring Board for Merck and as a consultant for BD, Cepheid, Roche, GE Healthcare, ClearPath, Guided Therapeutics and Gen-Probe/Hologic. Dr. Wentzensen has received cervical cancer screening assays in-kind or at reduced cost from BD, Cepheid, Hologic, and Roche.

Footnotes

Presented at the Annual Meeting American Association of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) in New Orleans, LA on April 15, 2016.

Financial Disclosure: The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 Mar 14; doi: 10.1309/AJCPTGD94EVRSJCG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, Katki HA, Kinney WK, Schiffman M, et al. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Apr;121(4):829–846. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182883a34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, Davey DD, Goulart RA, Garcia FA, et al. Use of Primary High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Testing for Cervical Cancer Screening: Interim Clinical Guidance. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jan 7; doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moyer VA. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jun 19;156(12):880–891. W312. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 131: Screening for cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Nov;120(5):1222–1238. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e318277c92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright TC, Jr, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Sharma K, Apple R. Interlaboratory variation in the performance of liquid-based cytology: insights from the ATHENA trial. Int J Cancer. 2014 Apr 15;134(8):1835–1843. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roland KB, Benard VB, Greek A, Hawkins NA, Manninen D, Saraiya M. Primary care provider practices and beliefs related to cervical cancer screening with the HPV test in Federally Qualified Health Centers. Prev Med. 2013 Nov;57(5):419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roland KB, Benard VB, Soman A, Breen N, Kepka D, Saraiya M. Cervical cancer screening among young adult women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013 Apr;22(4):580–588. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuzick J, Myers O, Hunt WC, Robertson M, Joste NE, Castle PE, et al. A population-based evaluation of cervical screening in the United States: 2008–2011. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014 May;23(5):765–773. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health NMDo, editor. Notifiable disease or conditions in New Mexico. 2012. http://nmhealth.org/publication/view/regulation/372/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gage JC, Hunt WC, Schiffman M, Katki HA, Cheung LC, Cuzick J, et al. Risk Stratification using Human Papillomavirus Testing among Women with Equivocally Abnormal Cytology: Results from a State-wide Surveillance Program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015 Oct 30; doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheeler CM, Hunt WC, Cuzick J, Langsfeld E, Pearse A, Montoya GD, et al. A population-based study of human papillomavirus genotype prevalence in the United States: baseline measures prior to mass human papillomavirus vaccination. Int J Cancer. 2013 Jan 1;132(1):198–207. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wheeler CM, Hunt WC, Cuzick J, Langsfeld E, Robertson M, Castle PE. The influence of type-specific human papillomavirus infections on the detection of cervical precancer and cancer: A population-based study of opportunistic cervical screening in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2014 Aug 1;135(3):624–634. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, Lorey T, Poitras NE, Cheung L, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Jul;12(7):663–672. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70145-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, et al. Benchmarking CIN 3+ risk as the basis for incorporating HPV and Pap cotesting into cervical screening and management guidelines. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2013 Apr;17(5 Suppl 1):S28–S35. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318285423c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gage JC, Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, et al. The low risk of precancer after a screening result of human papillomavirus-negative/atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance papanicolaou and implications for clinical management. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014 Nov;122(11):842–850. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, et al. Five-year risks of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer among women with HPV testing of ASC-US Pap results. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2013 Apr;17(5 Suppl 1):S36–S42. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182854253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castle PE, Fetterman B, Akhtar I, Husain M, Gold MA, Guido R, et al. Age-appropriate use of human papillomavirus vaccines in the U.S. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Aug;114(2):365–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gage JC, Katki HA, Schiffman M, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, et al. Age-stratified 5-year risks of cervical precancer among women with enrollment and newly detected HPV infection. Int J Cancer. 2014 Aug 18; doi: 10.1002/ijc.29143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rositch AF, Silver MI, Burke A, Viscidi R, Chang K, Duke CM, et al. The correlation between human papillomavirus positivity and abnormal cervical cytology result differs by age among perimenopausal women. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2013 Jan;17(1):38–47. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182503402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gravitt PE. The known unknowns of HPV natural history. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011 Dec;121(12):4593–4599. doi: 10.1172/JCI57149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuzick J, Myers O, Hunt WC, Saslow D, Castle PE, Kinney W, et al. Human papillomavirus testing 2007–2012: co-testing and triage utilization and impact on subsequent clinical management. Int J Cancer. 2015 Jun 15;136(12):2854–2863. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gage JC, Schiffman M, Hunt WC, Joste N, Ghosh A, Wentzensen N, et al. Cervical histopathology variability among laboratories: a population-based statewide investigation. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013 Mar;139(3):330–335. doi: 10.1309/AJCPSD3ZXJXP7NNB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoler MH, Wright TC, Jr, Sharma A, Apple R, Gutekunst K, Wright TL. High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Testing in Women With ASC-US Cytology: Results From the ATHENA HPV Study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011 Mar;135(3):468–475. doi: 10.1309/AJCPZ5JY6FCVNMOT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Results of a randomized trial on the management of cytology interpretations of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Jun;188(6):1383–1392. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A randomized trial on the management of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology interpretations. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 Jun;188(6):1393–1400. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.