Highlights

-

•

Retroperitoneal Castleman’s disease in the peripancreatic region is a rare entity.

-

•

Preoperative diagnosis is most often difficult and mimics malignant disease.

-

•

Surgical en bloc excision is the most commonly performed treatment due to diagnostic dilemma.

-

•

Preoperative biopsy in cases with strong clinical suspicion can avoid radical surgery.

Abbreviations: CD, Castleman’s disease; HV, hyaline vascular type of Castleman’s disease; PC, plasma cell type of Castleman’s disease

Keywords: Castleman’s disease, Retroperitoneum, Lymph node hyperplasia, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Castleman’s disease (CD) is an angio-follicular lymph node hyperplasia presenting as a localized or a systemic disease masquerading malignancy. The most common sites of CD are mediastinum, neck, axilla and pelvis. Unicentric CD in the peripancreatic region is very rare.

Presentation of case

We report a case of the 34-year-old lady presenting with epigastric pain for 3 months. Abdominal imaging revealed a retroperitoneal mass arising from the pancreas suspected to be neuroendocrine tumor. Tumor markers were not elevated. Complete surgical excision was performed and patient had uneventful recovery. Pathologic findings demonstrated localized hyaline-vascular type of Castleman’s disease.

Discussion

CD is a very rare cause for development of retroperitoneal mass. It is more frequent in young adults without predilection of sex. It can occur anywhere along the lymphoid chain. Abdominal and retroperitoneal locations usually present with symptoms due to the mass effect on adjacent organs. CD appears as a homogeneously hypoechoic mass on ultrasound and non-specific enhancing homogeneous mass with micro calcifications on computed tomography. Histologically, the hyaline vascular type demonstrates a follicular and inter-follicular capillary proliferation with peri-vascular hyalinization, with expansion of the mantle zones by a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of numerous small lymphocytes and plasma cells. The standard therapy of localized form is en bloc surgical excision as performed in our case.

Conclusion

Unicentric CD in the peripancreatic region is difficult to differentiate from pancreatic neoplasm preoperatively. However, preoperative biopsy in cases of high clinical suspicion can help in avoiding extensive surgery for this benign disease.

1. Introduction

Abdominal masses are a clinical enigma and pre-operative diagnosis is always difficult due to varied presentations of the tumors. This problem is more so with retroperitoneal masses [1]. Castleman’s disease (CD), or angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia, is an uncommon condition distinguished by the development of benign lymph node masses. This condition was first described in 1956 by Castleman et al. [2]. It has been described mainly in case reports and series, so the true incidence and prevalence of CD is difficult to ascertain [3]. The most common location of CD is mediastinum (70%) but the involvement of extrathoracic sites like neck, axilla and pelvis have also been reported [4]. Retroperitoneal CD in the peripancreatic region is a rare entity [5], [6]. We report a case of the 34-year-old lady with suspected pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor diagnosed to have Castleman’s disease on histological examination of resected specimen. This case has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [7].

2. Patient and observation

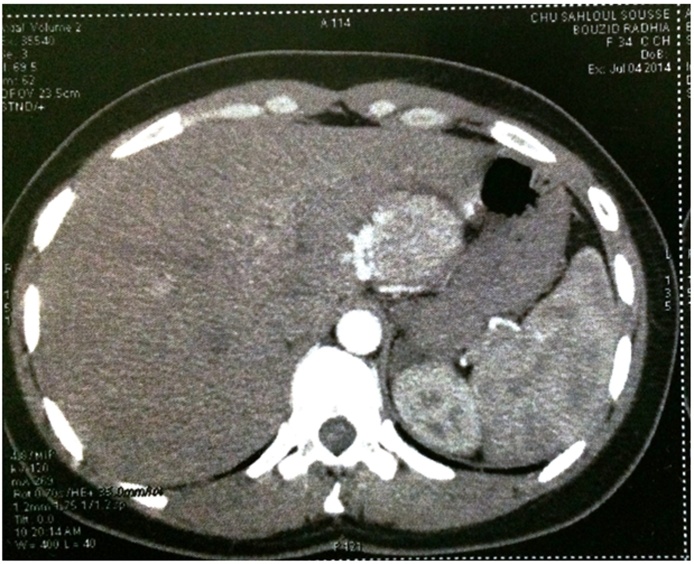

A 34-year-old lady, without past medical or surgical history, presented to our University hospital with epigastric pain for 3 months. Epigastric pain was dull aching in nature with the aggravation of pain after meals. There was no history of fever, night sweats, abdominal lump, decreased appetite, weight loss, or alteration of bowel habit. She has a history of smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for 10 years. Family history was non-contributory. Physical examination was unremarkable. Routine blood investigations including hematological and biochemical tests were normal. Values of the tumor markers were within normal range (Carcinoembryonic antigen: 0.9 ng/ml, Carbohydrate antigen 19-9:2 U/ml). Upper digestive endoscopy detected a bulge in the stomach near the lesser curvature due to extrinsic compression. Abdominal ultrasonography (USG) revealed a retroperitoneal tumor of size 5 × 5 × 3 cm probably arising from the pancreas. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed a solid, homogenous, hypervascular and well-delineated mass measuring 48 × 50 mm located in the retroperitoneum behind the body of pancreas (Fig. 1). The mass was in close contact with the branches of the celiac trunk. No significant deformation of adjacent retroperitoneal structures was observed. There was no evidence of abdominopelvic lymphadenopathy or intraperitoneal disease. Kidneys, spleen and liver were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging found a well-defined mass measuring 5 × 5 × 4 cm in the lesser sac, hypointense on T1 weighted and hyperintense on T2 weighted images with heterogeneous enhancement. It was in close contact with the body of the pancreas and the lesser curvature of the stomach.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal CT showing a hypervascular retroperitoneal mass arising from the peripancreatic region.

Based on the radiological findings, a provisional diagnosis of retroperitoneal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor was made and the patient was prepared for surgical resection. On exploration, the pancreas, liver, stomach and other organs appeared to be normal. The encapsulated mass was seen bulging through the lesser omentum and arising from the retroperitoneum close to the pancreatic body. The mass was completely excised along with its capsule with preservation of the surrounding organs.

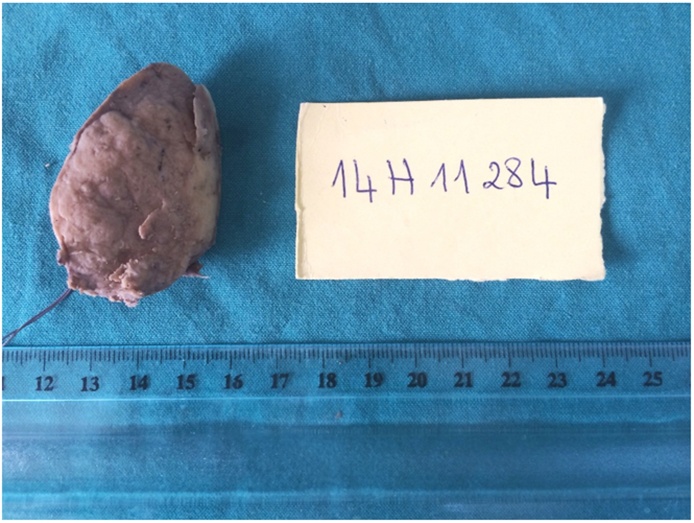

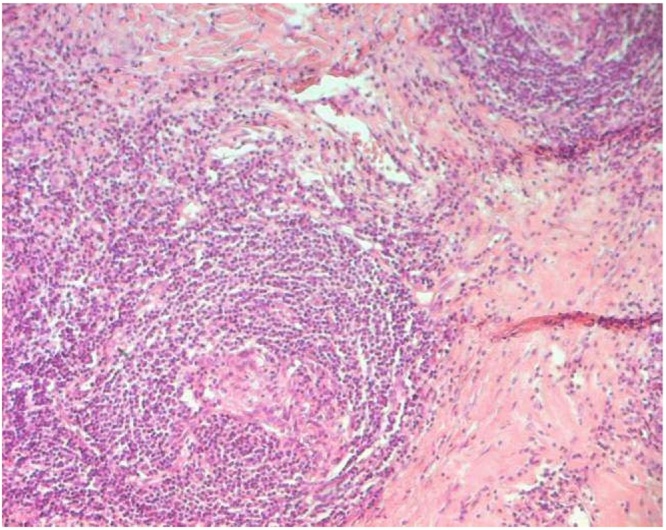

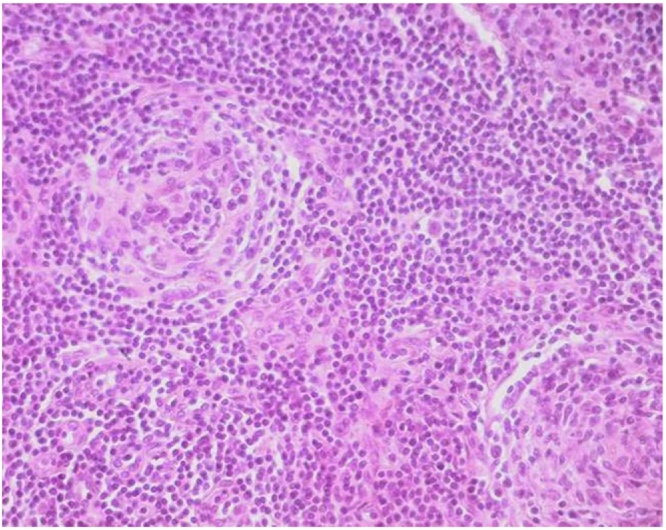

On gross examination, it was an encapsulated mass, measuring 5 × 6 × 3 cm with a yellowish color and a multinodular cut surface (Fig. 2). Microscopic examination showed enlarged lymphoid follicles with onion peel like appearance characterized by atrophic germinal centers with surrounding concentric rings of B-lymphocytes (Fig. 3). Inter-follicular areas showed extensive hyaline vascular stromal changes without aggregates of plasma cells (Fig. 4). There was no evidence of pancreatic tissue. Immunostaining for CD23 demonstrated the follicular dendritic network of residual germinal centers (Fig. 5). CD10 was also weakly positive in some of the transformed germinal centers and immunostaining for HHV-8 was negative. These findings were consistent with Castleman’s disease, hyaline vascular (angio-follicular) variant. Patient had uneventful postoperative recovery. After discharge, patient was clinically assessed in outpatient department every 3–4 months and CT abdomen was performed twice at 6 months and 1 year with no evidence of recurrence. The patient was satisfied with the treatment and is currently symptom free more than a year after surgery.

Fig. 2.

Macroscopic findings: an encapsulated mass measuring 5 × 6 × 3 cm with a yellowish grey color.

Fig. 3.

Lymphoid follicles with features of onion peel cell deposition with Inter-follicular areas showed extensive hyaline vascular stromal changes (HEx40).

Fig. 4.

Regressed germinal centers with hyperplastic dendritic cells and surrounded by concentric rings of B-lymphocytes (HEx200).

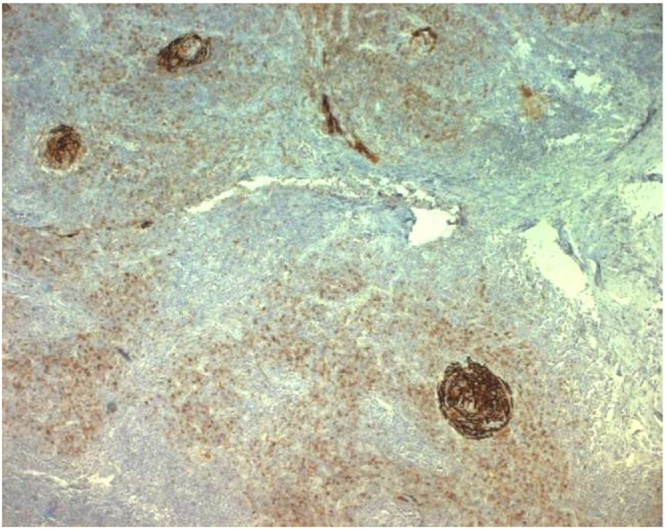

Fig. 5.

Immunostaining for CD23 demonstrated the characteristic follicular dendritic network of residual germinal centers.

3. Discussion

CD represents a very rare cause for development of retroperitoneal mass. CD is more common in young adults without predilection of sex, although age varies from 8 to 66 years [4]. CD may occur anywhere along the lymphoid chain. In 1972, Keller et al. subclassified CD into a hyaline-vascular (HV) type and a plasma-cell (PC) type based on their histologic features [4]. Clinically, CD can be divided into a localized form (unicentric disease) and a generalized form (multicentric disease). Clinical manifestations of CD are heterogeneous, ranging from asymptomatic discrete lymphadenopathy to recurrent episodes of diffuse lymphadenopathy with severe systemic symptoms [8]. The HV variety of CD is more common (90%) and is usually asymptomatic and presents as a localized disease [9], [10]. Abdominal and retroperitoneal locations may present with symptoms due to mass effect on adjacent organs as anorexia, weight loss, vomiting, urinary retention, and abdominal pain [11].

Radiologically, CD is seen as a homogeneously hypoechoic mass on USG and non-specific enhancing homogeneous mass with micro-calcifications on CT, both of which are not diagnostic as seen in our case [12]. Although, MRI is superior to CT as it shows better soft tissue delineation, but is also not definitive for the diagnosis of CD. Preoperative fine-needle aspiration cytology has no role in diagnosis because of its low specificity. So, a definitive diagnosis can only be made by pathological examination of the biopsy tissue or resected specimen.

Grossly, CD appears as an encapsulated homogenous mass with an orange-yellowish color [1]. Histologically, the HV type demonstrates a follicular and inter-follicular capillary proliferation with peri-vascular hyalinization and expansion of the mantle zones by a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of numerous small lymphocytes and plasma cells. The germinal centers typically form concentric rings, a phenomenon that known “onion skinning” [13]. Often, a single penetrating vessel is located at the center of the follicle. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell collections may be present [13].

Treatment of CD differs between localized and multifocal or systemic forms. The standard therapy for the localized form is en bloc surgical excision as performed in our case. As these lesions are hypervascular, embolization before surgery could be of help in reducing blood loss during surgery [14]. The five-year survival after resection is nearly 100% for the localized form. Recurrences have rarely been reported mainly in cases when excision was incomplete [15]. For the systemic form, no curative therapies have been found yet. Corticosteroid therapy, immunosuppressive drugs, chemotherapy and radiotherapy have been tried without any convincing results [12], [15], [16].

4. Conclusion

Unicentric CD, though a rare clinical entity, should be included in the differential diagnosis of peripancreatic masses. It’s a diagnostic challenge to differentiate it from pancreatic neoplasm. Accurate preoperative diagnosis by image-guided biopsy can prevent extensive surgery for this benign disease.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Written informed consent for the publication of this case report and all accompanying images was obtained from the patient and the patient’s family. Copies of the written consents are available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Funding

This study was not funded by any organization or institution.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Hospital Sahloul.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Author contribution

Study concept or design − NA, HA, AB.

Data collection − HA, NA.

Data interpretation − AB, HA, RG, MN, MG.

Literature review − HA, RG, NA, AB.

Drafting of the paper − NA, RG, AB.

Editing of the paper − NM, MG, MM.

Registration of research studies

This was a case report and not a clinical trial, this study does not require registration.

Guarantor

Ahlem Bdioui.

Nihed Abdessayed.

Acknowledgements

None.

Contributor Information

Ahlem Bdioui, Email: ahlem.bdioui@rns.tn, ahlembdioui@hotmail.com.

Houssem Ammar, Email: Hosshoss24@hotmail.fr.

Rahul Gupta, Email: rahul.g.85@gmail.com.

Nozha Mhamdi, Email: nozham@yahoo.com.

Marwa Guerfela, Email: guerfalamarwa@gmail.com.

Moncef Mokni, Email: moncefmokni@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Nirhale D.S., Bharadwaj R.N., Athavale V.S., Gupta R.K., Bora C. Castleman's disease-A rare diagnosis in the retroperitoneum. Indian. J. Surg. 2013;75:9–11. doi: 10.1007/s12262-011-0301-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castleman B., Iverson L., Menendez V.P. Localized mediastinal lymphnode hyperplasia resembling thymoma. Cancer. 1956;9:822–830. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195607/08)9:4<822::aid-cncr2820090430>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams A.D., Sanchez A., Hou J.S., Rubin R.R., Hysell M.E., Babcock B.D. Retroperitoneal Castleman's disease: advocating a multidisciplinary approach for a rare clinical entity. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2014;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller A.R., Hochholzer L., Castleman B. Hyaline vascular and plasma-cell types of giant lymph node hyperplasia of the mediastinum and other locations. Cancer. 1972;29:670–683. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197203)29:3<670::aid-cncr2820290321>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain S., Chatterjee S., Swain J.R., Rakshit P., Chakraborty P., Sinha S. Unicentric Castleman's disease masquerading pancreatic neoplasm. Case Rep. Oncol. Med. 2012;2012:793403. doi: 10.1155/2012/793403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bucher P., Chassot G., Zufferey G., Ris F., Huber O., Morel P. Surgical management of abdominal and retroperitoneal Castleman's disease. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2005;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P. for the SCARE group: the SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waisberg J., Satake M., Yamagushi N., Matos L.L., Waisberg D.R., Artigiani Neto R. Retroperitoneal unicentric Castleman's disease (giant lymph node hyperplasia): case report. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2007;125:253–255. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802007000400013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg M.A., Deluca S.A. Castleman’s disease. Am. Fam. Physician. 1989;49:151–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo H., Shen Y., Wang W.L., Zhang M., Li H., Wu Y.S. Castleman disease mimicked pancreatic carcinoma: report of two cases. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2012;10:154. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apodaca-Torrez F.R., Filho B.H., Beron R.I., Goldenberg A., Goldman S.M., Lobo E.J. Castleman’s disease mimetizing pancreatic tumor. JOP. 2012;13:94–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim T.J., Han J.K., Kim Y.H., Kim T.K., Choi B.I. Castleman disease of the abdomen: imaging spectrum and clinicopathologic correlations. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2001;25:207–214. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cronin D.M., Warnke R.A. Castleman disease: an update on classification and the spectrum of associated lesions. Adv Anat Patho. 2009;l16:236–246. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181a9d4d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiguchi H., Ishii T., Ishikawa Y., Masuda S., Asuwa N., Yamafuji K. Castleman’s disease of the abdomen and pelvis: report of three cases and a review of the literature. J. Gastroenterol. 1995;30:661–666. doi: 10.1007/BF02367795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shahidi H., Myers J.L., Kvale P.A. Castleman's disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1995;70:969–977. doi: 10.4065/70.10.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horster S., Jung C., Zietz C., Cohen C.D., Siebeck M., Goebel F.D. AIDS, multicentric Castleman's disease, and plamablastic leukemia: report of a long-term survival. Infection. 2004;32:296–298. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-3148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]