Abstract

Congenital generalized lipodystrophy (CGL) is a genetically heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by the absence of functional adipose tissue. We identified two pedigrees with CGL in the community of the Mestizo tribe in the northern region of Peru. Five cases, ranging from 15 months to 7 years of age, presented with generalized lipodystrophy, muscular prominence, mild intellectual disability, and a striking aged appearance. Sequencing of the BSCL2 gene, known to be mutated in type 2 CGL (CGL2; Berardinelli–Seip syndrome), revealed a homozygous deletion of exon 3 in all five patients examined, suggesting the presence of a founder mutation. This intragenic deletion appeared to be mediated by recombination between Alu sequences in introns 2 and 3. CGL2 in this population is likely underdiagnosed and undertreated because of its geographical, socio-economic, and cultural isolation.

Keywords: Berardinelli–Seip syndrome, BSCL2, congenital generalized lipodystrophy, molecular genetics, Mendelian disease

INTRODUCTION

Lipodystrophies are primarily characterized by abnormal distributions of fat tissues resulting from acquired or inherited causes [Garg, 2004]. These include congenital generalized lipodystrophy (CGL), a genetically heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by the nearly complete lack of functional adipocytes. Metabolic abnormalities such as hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance are also characteristic features of these disorders [Prieur et al., 2014; Cortes and Fernandez-Galilea, 2015; Patni and Garg, 2015]. CGL is usually caused by pathogenic variants in either the AGPAT2 or the BSCL2 genes, which are responsible for a milder CGL1 and a more severe CGL2 (Berardinelli–Seip syndrome), respectively [Van Maldergem et al., 2002; Agarwal et al., 2003; Haghighi et al., 2016]. A small number of patients with CAV1 mutations are reported in CGL3 [Kim et al., 2008] and PTRF mutations have been observed in CGL4 [Hayashi et al., 2009; Rajab et al., 2010]. The proteins encoded by these four genes are involved in the various steps of lipid droplet formation in adipocytes [Patni and Garg, 2015]. In particular, BSCL2 encodes a transmembrane protein, seipin, associated with lipid droplet biogenesis [Magre et al., 2001; Wee et al., 2014].

CGL2 or Berardinelli–Seip syndrome (OMIM# 269700) was originally described by Berardinelli [Berardinelli, 1954] and Seip [Seip, 1959] and is usually recognized during infancy because of the paucity of subcutaneous fat [Van Maldergem, 2012]. Due to the absence of functional adipose tissue, lipids are stored within other tissues, including liver and both skeletal and cardiac muscles. Hepatomegaly (a result of hepatosteatosis) and skeletal muscle hypertrophy are seen in virtually all cases [Van Maldergem et al., 2002]. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a significant cause of morbidity and is considered a specific endophenotype of CGL2 [Rheuban et al., 1986; Friguls et al., 2009]. Infantile cardiomyopathy has also been reported in a Pakistani AGPAT2 mutant case [Debray et al., 2013].

Since the initial identification of BSCL2 pathogenic variants as the causes of CGL2 [Magre et al., 2001], there have been a number of reports of BSCL2 disease-causing variants from European, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries [Van Maldergem et al., 2002; Agarwal et al., 2003; Shirwalkar et al., 2008; Rahman et al., 2013; Schuster et al., 2014; Akinci et al., 2016; Haghighi et al., 2016]. While most identified pathogenic variants are null mutations, the result of either nonsense, indel, or splicing mutations, a small number of missense variants have also been reported in CGL2 [Van Maldergem et al., 2002]. We now report a new set of pedigrees from northern Peru with a childhood onset of severe lipodystrophy and a novel homozygous variant in BSCL2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This group of Peruvian patients was initially referred to the Progeria Research Foundation (www.progeriaresearch.org) and subsequently to the International Registry of Werner Syndrome for a molecular genetic diagnosis of CGL. Consents to enroll in the genetic studies and allow the use of clinical and genetic data and the photographs in publications were signed by parents. The present study, including appropriate consent forms, has been approved by an Institutional Review Board of the University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Blood sample processing and exon sequencing were done as previously described [Friedrich et al., 2010]. Primers used to determine the breakpoints are listed in supplemental materials.

RESULTS

Clinical Reports

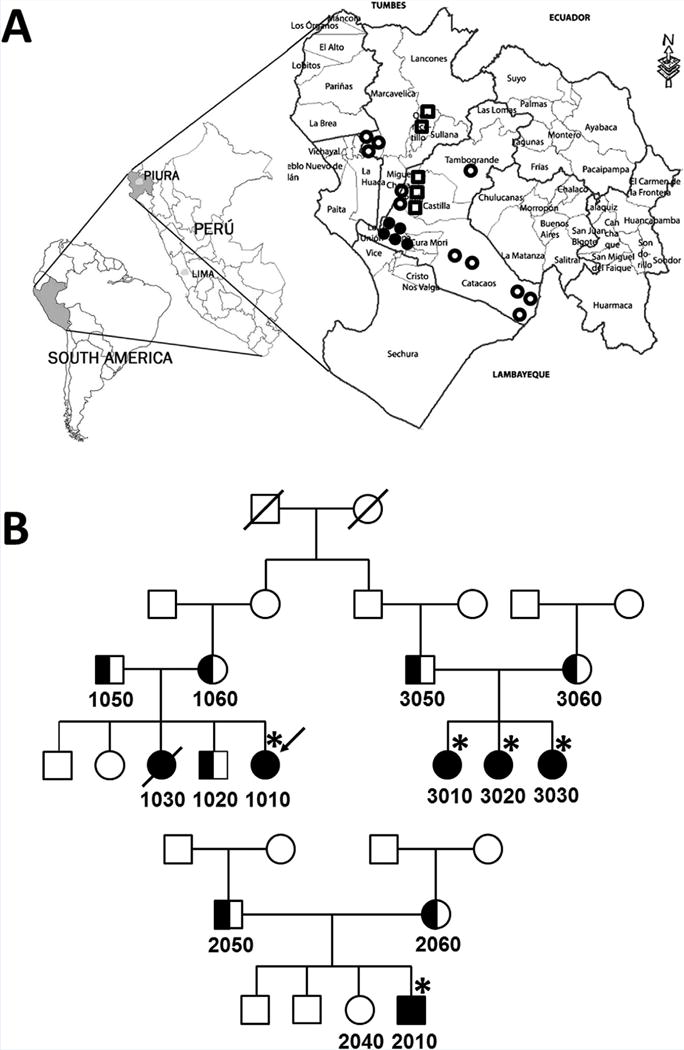

Both pedigrees are from a small community of the isolated Mestizo people who founded a remote rural village, Loma Negra (population ~ 2,500) approximately 100 years ago. It is located in the La Arena District of Piura Province in northern Peru (Fig. 1A). There is only limited access to regular medical care, and children are born at home. Consanguinity is strongly suspected because of the sharing of a few common last names among the villagers. The clinical features are summarized in Table I.

FIG. 1.

Peruvian pedigrees of the Berardinelli–Seip syndrome and their geographical locations. A: Geographic location of Loma Negra in Piura Province, Peru. Closed circles indicate genetically confirmed CGL2 patients. Open circles are clinically diagnosed CGL2 with no genetic confirmation. Open squares represent those reported in 1999 [Torres et al., 1999]. B: Pedigrees of three Peruvian families. Individuals who are clinically evaluated in person are marked (*). Individuals with assigned numbers of Registry# PERU are used in this study (see text).

TABLE I.

Clinical Features of Peruvian CGL2 Patients

| PERU1010 | PERU3010 | PERU3020 | PERU3030 | PERU2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 7y 6mo | 4y 1mo | 2y 5mo | 1y 5mo | 5y 5mo |

| Gender | F | F | F | F | M |

| Major criteria | |||||

| Generalized lipodystrophy | + | + | + | + | + |

| Acromegaloid features | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hepatomegaly | + | + | − | − | + |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | + | + | + | + | + |

| Acanthosis nigricans | + | + | − | − | + |

| Minor criteria | |||||

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | ND | ND | ND | ND | + |

| Developmental delay | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hirsutism | − | − | − | − | − |

| Early puberty | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bone cysts | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Prominent veins | + | + | + | − | + |

| Others | |||||

| Short stature | − | − | + | + | − |

| BMI | 17.1 | 16.2 | 15.2 | 12.2 | 16.7 |

| Premature graying of hair | + | + | − | − | − |

| Muscular prominence | + | + | + | + | + |

| Mild anemia | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hypercholesterolemia | − | − | − | − | − |

| Abnormal liver enzyme | + | − | − | − | + |

| Diabetes mellitus | + | − | − | − | − |

ND, not done.

Criteria has been described previously [Van Maldergem, 2012].

Pedigree 1—Registry# PERU 1010, PERU3010, PERU3020, and PERU3030

The proband (PERU1010) is a 7 year and 6-month-old girl who was small for gestational age, with a birth weight of 1.2 kg at full-term. Motor development was delayed; she began to walk at 3 years of age. She had generalized lipodystrophy in infancy, which gave her a striking progeroid appearance (Fig. 2A). On examination, her height was 122 cm (Z score = −0.30 using WHO reference) and her weight was 25.4 kg (Z score = 0.47). She had graying, thinning hair, lipodystrophy affecting the face and limbs, and acanthosis nigricans of the neck and arms. Cardiac physical examination did not show overt abnormalities. An examination by an ophthalmologist was normal. She appeared to have mild intellectual disability, but a formal evaluation could not be accomplished. She was 2 years delayed at school. Laboratory evaluation showed a mild microcytic anemia with hemoglobin 11.6 g/dl (normal range 12–16), hematocrit 33.6% (normal range 35–45), and MCV 66.7 fl (normal range 78–96). An elevated level of serum glucose was noted: 331.7 mg/dl (normal range 83–110). There was a marked elevation of HgA1C: 13.18% (normal range 4.5–5.9%). Liver enzymes were also elevated: the SGOT was 90.6 U/L (normal range 0–31), SGPT was 100.5 U/L (normal range 0–31), and GGT was 112 U/L (normal range 0–40). Her lipid profile showed a normal total cholesterol of 144.3 mg/dl (normal less than 200) and elevated triglycerides of 297.6 mg/dl (normal less than 100). The HDL was 27.4 mg/dl (normal range 40–56), the LDL was 57.38 mg/dl (normal less than 100), the VLDL was 59.52 mg/dl (normal range 10–50).

FIG. 2.

Clinical features of five Peruvian children affected by the Berardinelli–Seip syndrome: Registry# PERU1010 (A), at age 7 years 6 months: PERU2010 (B) at age 5 years 5 months. Note the acanthosis nigricans (elbow flexor creases) of PERU1010 and PERU2010 and the distended abdomen of PERU2010 associated with hepatomegaly. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com].

The family history was notable for a similarly affected sister (Registry# PERU1030) who died at age 18 years. She had severe joint pains and difficulty walking during the last year of her life. No autopsy was performed. There are three unaffected sibs (two males and one female).

Three girls (Registry# PERU 3010, PERU3020, and PERU3030) born to the son of a paternal uncle of the proband’s mother (second cousins) were also affected. The oldest (PERU 3010), 4 years and 1 month old, was delivered by Caesarean section because of fetal distress. Her birthweight was normal at 2.8 kg. At 4 years of age, her height was 97 cm (Z Score = −1.45) and she weighed 15.2 kg (Z Score = −0.46). Their normal mother’s height was 141 cm. The father’s height was not available. She has identical clinical signs of generalized lipodystrophy which started during infancy, a progeroid appearance, acanthosis nigricans, graying/loss of hair beginning at age 3 years, umbilical hernia, and hepatomegaly. At 49 months, she was evaluated using a standard screening assessment tool of pediatric growth and development endorsed by the Peruvian Ministry of Health, CRED (Crecimiento y Desarrollo, available at http://datos.minsa.gob.pe/sites/default/files/norma_cred.pdf). She did not meet the age appropriate milestones for a 3–4 year old child; namely to verbalize her first and last name (language), to copy a circle (fine motor), to know the value of an object (social), and buttoning and unbuttoning (coordination). Her gross motor development was also delayed; she began to walk at age 3 years, and could not walk on tip-toe.

Laboratory testing showed a mild anemia with hemoglobin 11.5 g/dl (normal 12–16) and hematocrit 31.6% (normal 35–45). Her glucose level was normal at 75.5 mg/dl (normal 83–110). Liver enzymes were also normal: SGOT 21.9 U/L (normal 0–31), SGPT 15.2 U/L (normal 0–31), and GGT 31 U/L (normal 0–40). Her lipid profiles showed total cholesterol 183.1 mg/dl (normal less than 200), HDL 21.3 mg/dl (normal 40–56), LDL 126.18 mg/dl (normal less than 100), VLDL 35.6 mg/dl (normal 10–50), and elevated triglycerides of 178.1 mg/dl (normal less than 100).

The middle sister (PERU 3020) was 2 years 5 months old (height 79 cm, Z Score = −3.13; weight 9.5 kg; Z Score = −1.92). She also had generalized lipodystrophy noted during infancy. At 29 months old, using the CRED for children less than 30 months old, she was delayed in the following domains: motor (could not make a tower using seven cubes) language (say three simple sentences), and social (unscrew a cap to look inside a bottle). Laboratory testing showed a mild anemia with hemoglobin 11.9 g/dl (normal 12–16), hematocrit 31.7% (normal 35–45), and MCV 78.1 fl (normal 78–96). The glucose level was normal at 70.67 mg/dl (normal range 83–110). Liver enzymes were SGOT 30.1 U/L (normal 0–31), SGPT 21.3 U/L (normal 0–31), and GGT was 63 U/L (normal 0–40). Her lipid profile showed a total cholesterol 189.9 mg/dl (normal less than 200), HDL 11.7 mg/dl (normal 40–56), and LDL 89.3 mg/dl (normal less than 100), and elevated triglycerides of 444.5 mg/dl (normal less than 100).

The youngest sister (PERU 3030) was 17 months old (length 66 cm, Z Score = −4.80; weight 5.3 kg, Z Score = −3.83). She had generalized lipodystrophy and at 17 months, she did not meet age expected milestones of putting a bean inside a bottle (fine motor), eating at a table with others or pulling a toy (social), and language (identify common objects). Laboratory evaluation showed a mild anemia with hemoglobin 10.8 g/dl (normal 12–16) and hematocrit 31.7% (normal 35–45) and elevated triglycerides of 288 mg/dl (normal than 100). Other testing results were glucose 79.7 mg/dl (normal 83–110), SGOT 31.7 U/L (normal 0–31), SGPT 25.5 U/L (normal 0–31), GGT 12 U/L (normal 0–40), a total cholesterol of 186.1 mg/dl (normal less than 200), HDL was 20 mg/dl (normal 40–56), LDL 108.5 mg/dl (normal less than 100), and VLDL 57.6 mg/dl (normal 10–50).

Pedigree 2—Registry# PERU2010

A 5 year and 4-month-old boy from the same village in Loma Negra, Peru, was also evaluated (Fig. 2B). He was born at home with a birthweight of 4 kg. He began to exhibit lipodystrophy at age 2 years. At age 5 years 5 months, his height was 120 cm (Z score = 1.73) and his weight was 24 kg (Z score = 1.99). He had generalized lipodystrophy and extensive acanthosis nigricans of the elbow flexor creases and dorsal regions of the ankles. He had normal dark scalp hair, a distended abdomen, an umbilical hernia, and hepatosplenomegaly. A neurological examination revealed limited speech, and he was delayed by 1 year at school. Laboratory evaluation showed a mild anemia with hemoglobin 11.3 g/dl (normal 12–16) and hematocrit 32.5% (normal 35–45) and a normal level of glucose, 83.4 mg/dl (normal range 83–110). Liver enzymes were also elevated: SGOT 126.4 U/L (normal 0–31), SGPT 114.3 U/L (normal range 0–31), and GGT 81 U/L (normal range 0–40). Her lipid profile showed a total cholesterol of 152.1 mg/dl (normal less than 200), HDL 33.5 mg/dl (normal 40–56), the LDL was 94.7 mg/dl (normal less than 100), the VLDL was 23.8 mg/dl (normal 10–50), and triglycerides 119.4 mg/dl (normal less than 100). Chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly and echocardiography revealed mild mitral and tricuspid insufficiencies and evidence of mild cardiac hypertrophy.

None of these patients have received any drug treatments or dietary supplements to date.

Sequencing Analysis of the BSCL2 Gene

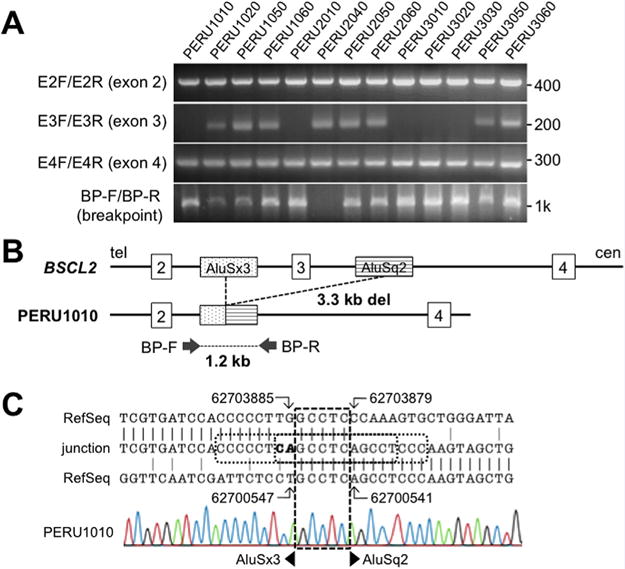

Initial Sanger sequencing of BSCL2 ruled out mutations in all exons except for exon 3, which repeatedly failed to amplify, suggesting a deletion involving exon 3. We, therefore, searched for a deletion between exons 2 and 4 (Fig. 3A). PCR using primers located within approximately 3 kb surrounding exon 3 failed to amplify any products in patient DNAs. Using the primers closest to the deleted region, BSCL2_BP-F (5′-TCCCAGAGAGTCTTGCGTCT-3′) and BP-R (5′-CTCCTCCCTTCAAAAGTGTGAC-3′), a PCR product of 1.2 kb was amplified from patient DNA (Fig. 3A and B). Sequence alignment revealed breakpoints of a 3,339 bp deletion in introns 2 and 4 (Fig. 3C). The breakpoint in intron 2 was within the AluSx3 (chr11:62703838–62704153) and that in intron 4 was within the AluSq2 (chr11:62700359–62700665), with overlapping GCCTC at ch11: 62703884–62703880 and 62700546–62700542. The overall similarity of these two Alu repeats was 83% (E value = 2e-27), suggesting an intragenic homologous recombination as the primary mutational mechanism. In addition, there was an insertion of an adjacent adenine residue (5′ with respect to the BSCL2 gene) in the overlapping GCCTC, creating a repeat of CCC CCT CAG CCT CAG CCT CCC at the junction (c.213-1336_c.294 + 1921delinsCA). This deletion would cause an 82 bp deletion at the mRNA level (r.213_294del), resulting in a frame shift and premature termination (p.Thr72Cysfs*2).

FIG. 3.

Molecular analysis of the BSCL2 mutation in Peruvian pedigrees. A: PCR results of BSCL2 exon 2–4 and the breakpoints of the PCR product using BP-F and BP-R primers. Eleven Sample IDs correspond to those in the pedigrees. Numbers on the right side are the positions of the closest markers. B: Diagram of the exon 2–4 region of BSCL2 gene. Top line represents the diagram of the wild-type allele with the location of the deletion breakpoints. Bottom line shows the diagram of the deleted allele. Only those Alu sequences involved in the deletions are shown. C: Breakpoint sequence in the DNA of the proband, PERU1010. The patient sequence (middle) was aligned to introns 2 (top) and 4 (bottom) of the chr 11 RefSeq, NG_008461.1 using the genomic coordinates of the GRCh38/hg38 assembly. The broken square shows the overlapping GCCTC. The dotted square indicates the region of short repeats present only in the recombined allele. Bold letters (CA) emphasize nucleotides that are not aligned to either reference sequences. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com].

Analysis of DNA samples from all available family members showed an absence of exon 3 in all five affected individuals; it was present, however, in an unaffected sibling and in both of the parents. The 1,210-bp breakpoint PCR product was seen in all of the patients and parents confirming the obligatory heterozygosity of parents (Fig. 3A and B).

The disease frequency in Negra Loma is approximately 0.0020 (five patients in a population of 2,452 as of June 2016). The mutant allele frequency (q) was calculated to be 0.045 and the heterozygote frequency was calculated to be 0.086 (1 in 11.6 persons). This unusually high frequency of heterozygotes and a previous case report of Peruvian Berardinelli–Seip syndrome [Torres et al., 1999] prompted us to search for additional families in neighboring areas. Thus far, an additional 10 cases with very similar clinical features have been identified in Piura and surrounding regions by local physicians (authors, NP and YB) (Fig. 1A). Their ages range from 20 months to 17 years. The anticipated genetic diagnoses of these subjects have not yet been confirmed.

DISCUSSION

We identified a novel BSCL2 mutation, c.213-1336_c.294+1921 delinsCA, which is expected to result in p.Thr72Cysfs*2, among classical Berardinelli–Seip syndrome patients in northern Peru. This null mutation was shared by five patients from two pedigrees, indicating the presence of a founder mutation. All five cases had a nearly complete lack of subcutaneous fat. Muscular prominence, another common feature of CGL, was found in all five patients. Other typical features included: acanthosis nigricans, hepatomegaly, diabetes mellitus, and mild intellectual disability. Microcytic anemia was also seen in all five cases; this is not a typical feature of Berardinelli–Seip syndrome, and more likely reflects poor nutritional status such as iron deficiency, although we were not able to perform iron studies.

One deceased case from our study (Registry# PERU1030) was reported to have died of a “heart problem.” Although detailed information concerning the nature of the pathophysiology was not available, it is quite possible that she have suffered from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a feature of Berardinelli–Seip syndrome [Friguls et al., 2009; Debray et al., 2013].

The oldest patient, PERU1010 (age 7 years and 6 months) showed evidence of hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes mellitus, and mild liver function abnormalities, conditions frequently seen in patients with the Berardinelli–Seip syndrome [Van Maldergem et al., 2002; Van Maldergem, 2012; Haghighi et al., 2016]. The age of onset is unknown, she had no prior laboratory testing. The youngest patient (age 17 months, PERU 3030), exhibited hypertriglyceridemia but had no evidence of diabetes or liver dysfunction. This patient, therefore, did not yet meet the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of CGL2 (three major criteria or two major and minor criteria) (Table I) [Van Maldergem, 2012], probably because of the early stage of the disease. Due to the limited demographic information of the Mestizo tribe, population-specific growth metrics could not be obtained. Although short stature was seen in two patients (PERU3020 and PERU3030) using World Health Organization (WHO) standards, we were unable to conclude that this was a feature of the CGL2 phenotype.

All five of our cases were said to have had evidence of mild intellectual disability or developmental delay. This is in agreement with two previous genotype–phenotype studies of CGL2, which reported that approximately 80% of the BSCL2 mutant patients had some degree of intellectual disability [Van Maldergem et al., 2002; Agarwal et al., 2003]. There appeared to be no clear correlation, however, between intellectual ability and the type of mutations, including a missense mutation, p. Ala112Pro [Van Maldergem et al., 2002].

An interesting recently described BSCL2-related clinical entity includes encephalopathy. This type of neurodegeneration has been observed in certain Spanish pedigrees described as cases of progressive encephalopathy, with or without lipodystrophy (PELD) [Guillen-Navarro et al., 2013]. The underling BSCL2 mutation, c.985C > T mutation, results in exon 7 skipping [Guillen-Navarro et al., 2013]. Infant mortality was observed in patients with at least one c.985C > T allele. Interestingly, mutant message containing exon 7 skipping was expressed at higher levels than wild-type BSCL2 messages. This led to the accumulation of truncated products, p.Try289Leufs*64, in the central nervous system, presumably a cause of neurodegeneration [Guillen-Navarro et al., 2013]. In our patients, we were unable to determine the expression levels of our exon 3 deletion allele relative to that of wild-type alleles due to a lack of patient materials. The possibility that the truncated exon deletion product in our patient, p.Thr72Cysfs*2, may play a role in the pathogenesis of our cases deserves further research.

BSCL2 mutations have also been reported for autosomal dominant neuropathies, with some overlaps with distal hereditary motor neuropathy type V(a) and Silver spastic paraplegia syndrome type 17 [Windpassinger et al., 2004; van de Warrenburg et al., 2006; Cafforio et al., 2008; Brusse et al., 2009; Rakocevic-Stojanovic et al., 2010], suggesting a role of seipin in neurotransmission [Wei et al., 2014].

Our breakpoint analysis suggests that Alu-mediated intragenic recombination can be a mechanism of deletional mutation in CGL2, as reported in other loci that undergo non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) following the ectopic cross-over of repeat sequences [Oshima et al., 2009, 2011; Liu et al., 2012]. Alignments of breakpoint sequences revealed two interesting features, raising additional mechanistic possibilities. The first is the presence of an adenine residue at the junction that is not in the reference sequence. Double strand breaks might have occurred by chance as a founder mutation in either intron 2 or 4 that was subsequently repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or NAHR. It is not uncommon that extra nucleotides are inserted during this process, in this case an A residue. A second interesting feature is the presence of short repeat sequence (CCC CCT CAG CCT CAG CCT CCC) at the junction. It is possible that a T-to-A substitution at Ch11: 62700547 in intron 4 occurred during mitosis, creating a short repeat of CAG CCT CAG CCT. Such substitutions might cause regional genomic instability and could trigger a genomic deletion as a secondary event [Oshima et al., 2009].

Despite the high frequency of the CGL2 patients in northern Peru, there have been no previous reports of genetic characterizations of this cohort. Our calculated carrier frequency of ~1 in 12 for this small highly inbred population should be viewed as only a tentative estimate, as it may well be the result of an ascertainment bias. Socio-economic factors such as low income (average yearly income ~$500), illiteracy, and lack of appropriate medical care are likely confounders. As the awareness of this disorder increases, a clearer picture of the extent of CGL2 in this unique population will be revealed. Although there is no cure for CGL, favorable results have been reported with the use of injections of recombinant methionyl human leptin (metreleptin) [Patni and Garg, 2015; Meehan et al., 2016]. Efforts are underway to provide more comprehensive clinical evaluations and to provide pharmacological interventions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Leslie Gordon and the Progeria Research Foundation for the referral of the patients. This work was supported by a NIH grants, R24AG42328 and R01CA210916 (Martin/Oshima).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

References

- Agarwal AK, Simha V, Oral EA, Moran SA, Gorden P, O’Rahilly S, Zaidi Z, Gurakan F, Arslanian SA, Klar A, Ricker A, White NH, Bindl L, Herbst K, Kennel K, Patel SB, Al-Gazali L, Garg A. Phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity in congenital generalized lipodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4840–4847. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinci B, Onay H, Demir T, Ozen S, Kayserili H, Akinci G, Nur B, Tuysuz B, Nuri Ozbek M, Gungor A, Yildirim Simsir I, Altay C, Demir L, Simsek E, Atmaca M, Topaloglu H, Bilen H, Atmaca H, Atik T, Cavdar U, Altunoglu U, Aslanger A, Mihci E, Secil M, Saygili F, Comlekci A, Garg A. Natural history of congenital generalized lipodystrophy: A nationwide study From Turkey. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:2759–2767. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardinelli W. An undiagnosed endocrinometabolic syndrome: Report of 2 cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1954;14:193–204. doi: 10.1210/jcem-14-2-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusse E, Majoor-Krakauer D, de Graaf BM, Visser GH, Swagemakers S, Boon AJ, Oostra BA, Bertoli-Avella AM. A novel 16p locus associated with BSCL2 hereditary motor neuronopathy: A genetic modifier? Neurogenetics. 2009;10:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0193-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafforio G, Calabrese R, Morelli N, Mancuso M, Piazza S, Martinuzzi A, Bassi MT, Crippa F, Siciliano G. The first Italian family with evidence of pyramidal impairment as phenotypic manifestation of Silver syndrome BSCL2 gene mutation. Neurol Sci. 2008;29:189–191. doi: 10.1007/s10072-008-0937-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes VA, Fernandez-Galilea M. Lipodystrophies: Adipose tissue disorders with severe metabolic implications. J Physiol Biochem. 2015;71:471–478. doi: 10.1007/s13105-015-0404-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debray FG, Baguette C, Colinet S, Van Maldergem L, Verellen-Dumouin C. Early infantile cardiomyopathy and liver disease: A multisystemic disorder caused by congenital lipodystrophy. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109:227–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich K, Lee L, Leistritz DF, Nurnberg G, Saha B, Hisama FM, Eyman DK, Lessel D, Nurnberg P, Li C, Garcia FVMJ, Kets CM, Schmidtke J, Cruz VT, Van den Akker PC, Boak J, Peter D, Compoginis G, Cefle K, Ozturk S, Lopez N, Wessel T, Poot M, Ippel PF, Groff-Kellermann B, Hoehn H, Martin GM, Kubisch C, Oshima J. WRN mutations in Werner syndrome patients: Genomic rearrangements, unusual intronic mutations and ethnic-specific alterations. Hum Genet. 2010;128:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0832-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friguls B, Coroleu W, del Alcazar R, Hilbert P, Van Maldergem L, Pintos-Morell G. Severe cardiac phenotype of Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy in an infant with homozygous E189X BSCL2 mutation. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52:14–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A. Acquired and inherited lipodystrophies. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1220–1234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra025261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillen-Navarro E, Sanchez-Iglesias S, Domingo-Jimenez R, Victoria B, Ruiz-Riquelme A, Rabano A, Loidi L, Beiras A, Gonzalez-Mendez B, Ramos A, Lopez-Gonzalez V, Ballesta-Martinez MJ, Garrido-Pumar M, Aguiar P, Ruibal A, Requena JR, Araujo-Vilar D. A new seipin-associated neurodegenerative syndrome. J Med Genet. 2013;50:401–409. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi A, Kavehmanesh Z, Salehzadeh F, Santos-Simarro F, Van Maldergem L, Cimbalistiene L, Collins F, Chopra M, Al-Sinani S, Dastmalchian S, de Silva DC, Bakhti H, Garg A, Hilbert P. Congenital generalized lipodystrophy: Identification of novel variants and expansion of clinical spectrum. Clin Genet. 2016;89:434–441. doi: 10.1111/cge.12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi YK, Matsuda C, Ogawa M, Goto K, Tominaga K, Mitsuhashi S, Park YE, Nonaka I, Hino-Fukuyo N, Haginoya K, Sugano H, Nishino I. Human PTRF mutations cause secondary deficiency of caveolins resulting in muscular dystrophy with generalized lipodystrophy. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2623–2633. doi: 10.1172/JCI38660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CA, Delepine M, Boutet E, El Mourabit H, Le Lay S, Meier M, Nemani M, Bridel E, Leite CC, Bertola DR, Semple RK, O’Rahilly S, Dugail I, Capeau J, Lathrop M, Magre J. Association of a homozygous nonsense caveolin-1 mutation with Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1129–1134. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Carvalho CM, Hastings PJ, Lupski JR. Mechanisms for recurrent and complex human genomic rearrangements. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magre J, Delepine M, Khallouf E, Gedde-Dahl T, Jr, Van Maldergem L, Sobel E, Papp J, Meier M, Megarbane A, Bachy A, Verloes A, d’Abronzo FH, Seemanova E, Assan R, Baudic N, Bourut C, Czernichow P, Huet F, Grigorescu F, de Kerdanet M, Lacombe D, Labrune P, Lanza M, Loret H, Matsuda F, Navarro J, Nivelon-Chevalier A, Polak M, Robert JJ, Tric P, Tubiana-Rufi N, Vigouroux C, Weissenbach J, Savasta S, Maassen JA, Trygstad O, Bogalho P, Freitas P, Medina JL, Bonnicci F, Joffe BI, Loyson G, Panz VR, Raal FJ, O’Rahilly S, Stephenson T, Kahn CR, Lathrop M, Capeau J. Identification of the gene altered in Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy on chromosome 11q13. Nat Genet. 2001;28:365–370. doi: 10.1038/ng585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan CA, Cochran E, Kassai A, Brown RJ, Gorden P. Metreleptin for injection to treat the complications of leptin deficiency in patients with congenital or acquired generalized lipodystrophy. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9:59–68. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2016.1096772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima J, Lee JA, Breman AM, Fernandes PH, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Ward PA, Wolfe LA, Eng CM, Del Gaudio D. LCR-initiated rearrangements at the IDS locus, completed with Alu-mediated recombination or non-homologous end joining. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:516–523. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima J, Magner DB, Lee JA, Breman AM, Schmitt ES, White LD, Crowe CA, Merrill M, Jayakar P, Rajadhyaksha A, Eng CM, del Gaudio D. Regional genomic instability predisposes to complex dystrophin gene rearrangements. Human Genet. 2009;126:411–423. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0679-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patni N, Garg A. Congenital generalized lipodystrophies-new insights into metabolic dysfunction. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:522–534. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieur X, Le May C, Magre J, Cariou B. Congenital lipodystrophies and dyslipidemias. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2014;16:437. doi: 10.1007/s11883-014-0437-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman OU, Khawar N, Khan MA, Ahmed J, Khattak K, Al-Aama JY, Naeem M, Jelani M. Deletion mutation in BSCL2 gene underlies congenital generalized lipodystrophy in a Pakistani family. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:78. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajab A, Straub V, McCann LJ, Seelow D, Varon R, Barresi R, Schulze A, Lucke B, Lutzkendorf S, Karbasiyan M, Bachmann S, Spuler S, Schuelke M. Fatal cardiac arrhythmia and long-QT syndrome in a new form of congenital generalized lipodystrophy with muscle rippling (CGL4) due to PTRF-CAVIN mutations. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakocevic-Stojanovic V, Milic-Rasic V, Peric S, Baets J, Timmerman V, Dierick I, Pavlovic S, De Jonghe P. N88S mutation in the BSCL2 gene in a Serbian family with distal hereditary motor neuropathy type V or Silver syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2010;296:107–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheuban KS, Blizzard RM, Parker MA, Carter T, Wilson T, Gutgesell HP. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in total lipodystrophy. J Pediatr. 1986;109:301–302. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster J, Khan TN, Tariq M, Shaiq PA, Mabert K, Baig SM, Klar J. Exome sequencing circumvents missing clinical data and identifies a BSCL2 mutation in congenital lipodystrophy. BMC Med Genet. 2014;15:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-15-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seip M. Lipodystrophy and gigantism with associated endocrine manifestations. A new diencephalic syndrome? Acta Paediatr. 1959;48:555–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirwalkar HU, Patel ZM, Magre J, Hilbert P, Van Maldergem L, Mukhopadhyay RR, Maitra A. Congenital generalized lipodystrophy in an Indian patient with a novel mutation in BSCL2 gene. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:S317–S322. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres R, Ballona R, Caytano M. Síndrome de Seip Berardinelli: Reporte de 5 casos en el Instituto de Salud del Niño. Folia Dermatol (Perú) 1999;10:43–47. [Google Scholar]

- van de Warrenburg BP, Scheffer H, van Eijk JJ, Versteeg MH, Kremer H, Zwarts MJ, Schelhaas HJ, van Engelen BG. BSCL2 mutations in two Dutch families with overlapping Silver syndrome-distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16:122–125. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Maldergem L. In: Berardinelli-Seip Congenital Lipodystrophy. Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH, Bird TD, Fong CT, Mefford HC, Smith RJH, Stephens K, editors. Seattle WA: GeneReviews(R); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Maldergem L, Magre J, Khallouf TE, Gedde-Dahl T, Jr, Delepine M, Trygstad O, Seemanova E, Stephenson T, Albott CS, Bonnici F, Panz VR, Medina JL, Bogalho P, Huet F, Savasta S, Verloes A, Robert JJ, Loret H, De Kerdanet M, Tubiana-Rufi N, Megarbane A, Maassen J, Polak M, Lacombe D, Kahn CR, Silveira EL, D’Abronzo FH, Grigorescu F, Lathrop M, Capeau J, O’Rahilly S. Genotype-phenotype relationships in Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy. J Med Genet. 2002;39:722–733. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.10.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee K, Yang W, Sugii S, Han W. Towards a mechanistic understanding of lipodystrophy and seipin functions. Biosci Rep. 2014;34:e00141. doi: 10.1042/BSR20140114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Soh SL, Xia J, Ong WY, Pang ZP, Han W. Motor neuropathy-associated mutation impairs Seipin functions in neurotransmission. J Neurochem. 2014;129:328–338. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windpassinger C, Auer-Grumbach M, Irobi J, Patel H, Petek E, Horl G, Malli R, Reed JA, Dierick I, Verpoorten N, Warner TT, Proukakis C, Van den Bergh P, Verellen C, Van Maldergem L, Merlini L, De Jonghe P, Timmerman V, Crosby AH, Wagner K. Heterozygous missense mutations in BSCL2 are associated with distal hereditary motor neuropathy and Silver syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:271–276. doi: 10.1038/ng1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]