Abstract

Retinal diseases are significant by increasing problem in every part of the world. While excellent treatment has emerged for various retinal diseases, treatment for early disease is lacking due to an incomplete understanding of all molecular events. With aging, there is a striking accumulation of neutral lipids in Bruch’s membrane. These neutral lipids leads to the creation of a lipid wall at the same locations where drusen and basal linear deposit, pathognomonic lesions of Age-related macular degeneration, subsequently form. High lipid levels are also known to cause endothelial dysfunction, an important factor in the pathogenesis of Diabetic Retinopathy. Various studies suggest that 20 % of Retinal Vascular Occlusion is connected to hyperlipidemia. Biochemical studies have implicated mutation in gene encoding ABCA4, a lipid transporter in pathogenesis of Stargardt disease. This article reviews how systemic and local production of lipids might contribute to the pathogenesis of above retinal disorders.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration, Diabetic retinopathy, Retinal vascular occlusion, Stargardt disease, Lipids

Introduction

The retina is a complex neurosensory tissue comprised of at least six neuronal cell types that are organized into distinct cell layers, in addition to glia (e.g., Müller cells) and astrocytes. So far as lipids are concerned, interest in the structures and function of the retina may extend into two directions; first the retina may be regarded as an organ for photoreceptor probably depending on lipid-soluble pigments, and secondly as a mechanism for neuronal transmission and integration, since it represents an outlying portion of the brain and like the latter, contains large amount of lipid both in its nerve fibers and in its synaptic connections.

Recent studies of lipids and lipid metabolism in the retina have focused on disease processes caused by either an over-abundance or, in some instances, a deficiency of specific lipid species within retinal cells or their surrounding extracellular environment, often resulting in toxic insult to these cells and ensuing retinal dysfunction, cell death, and progressive retinal degeneration [1].

In this paper, we will explore the various aspects of how lipids might contribute to the pathogenesis of retinal vascular disease like Diabetic Retinopathy, Retinal Vascular Occlusion (RVOs) and macular disorders like AMD (age-related macular degeneration) and Stargardt disease.

Lipids and AMD

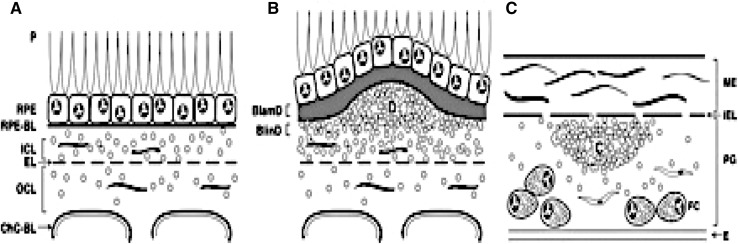

With chronological aging, Bruch’s membrane (BrM) thickens and develops heterogeneous deposits called basal deposits. The location and composition of basal deposits help to distinguish aging from AMD changes. The earliest age-related deposits are seen within the outer collagenous layer, and occur as early as 19 years of age [2]. Deposits between the RPE cell and its basement membrane, known as basal laminar deposits or BlamD (Fig. 1), are also an age-related change when thin and homogeneous in composition. When BlamDs thicken and accumulate heterogeneous debris, “long spacing collagen,” lipoproteins, and inflammatory proteins, they are associated histopathologically with AMD. When deposits accumulate within the inner collagenous layer, they are designated as basal linear deposits, or BlinDs (Fig. 1), one of the strongest histopathological markers for AMD. When sufficient debris, including lipid, accumulates within BlinD to form a mound, it can be seen clinically as large drusen (>125 μm) [3, 4].

Fig. 1.

ARMD pathogenesis. ARMD lesions versus plaque. Schematic cross-sections of RPE/BrM complex from a normal eye (a) and an eye with ARMD (b), compared with atherosclerotic arterial intima (c). Endothelium and vascular lumens (choriocapillary, a, b; artery, c) are at the bottom. Small circles indicate EC-rich lipoproteins, native and modified. P photoreceptors, RPE retinal pigment epithelium, RPE-BL RPE basal lamina, ICL inner collagenous layer, EL elastic layer, OCL outer collagenous layer, ChC-Bl basal lamina of choriocapillary endothelium. b BlamD basal laminar deposit, BlinD basal linear deposit, D druse. c ME musculo-elastic layer, IEL internal elastic layer, C lipid-rich core, PG proteoglycan layer, FC foam cells

Lipid particles accumulate within Bruch’s membrane in the exact location and prior to the development of basal deposits or drusen. Sarks et al. [5] first described these lipid particles as membranous debris within BrM, basal deposits, and drusen within the macula. The presence of membranous debris seen on histopathological examination corresponds to large drusen and severe RPE pigmentary changes in the central macula that are seen on clinical examination [5–9]. The Curcio lab has found that much of the membranous debris is actually lipoprotein particles [6].

Recent studies have shown that the lipoprotein particles within Bruch’s membrane are distinct from plasma lipoproteins and have been found to contain free and esterified cholesterol [10], phosphatidylcholine (PC), and apolipoprotein B100 [11]. Curcio et al. found that esterified cholesterol comprised 60 % of total cholesterol within these lipoproteins, and esterified cholesterol was sevenfold higher in the macula than periphery [12]. Drusen contains neutral lipids, with long chain fatty acid cholesteryl esters and nonesterified cholesterol. Drusen also contains at least 29 different proteins, including apolipoproteins (e.g., apoE, apoB) [13, 14]. These components suggest that the innate immune response is involved in drusen formation.

Accumulation of lipoprotein particles in the inner collagenous layer with aging, and their presence within drusen, basal laminar, and linear deposits suggests that their deposition is a critical antecedent event in the formation of these histopathological markers of AMD. AMD lesion formation has thus been conceptualized as sharing mechanisms with atherosclerotic plaque formation (Fig. 1) where LDL retention within the arterial wall initiates a cascade of pathologic events called the “response to retention” hypothesis [15]. In atherosclerosis, apolipoprotein B100 lipoproteins become trapped and then oxidatively modified. These modifications stimulate different biological processes including innate immune system-mediated inflammation, which induces a cascade of pathologic events that culminate in atherosclerotic plaques [16]. In AMD, the following evidence supports the “response to retention” hypothesis: (1) apoB100-containing lipoproteins accumulate in BrM in the same location as basal deposits and drusen, (2) oxidatively modified proteins and lipids are present in BrM; and (3) the accumulation of inflammatory mediators within drusen and basal deposits indicates a role for the innate immune response [17].

To date, epidemiological studies on the association between serum lipid and AMD risk have been inconsistent [18–26]. Part of this variability may have resulted from reporting different forms and stages of AMD with different lipid profiles. For example, several studies have not found an association between serum lipid profile and AMD risk [18, 20, 23]. Elevated HDL but not total cholesterol was associated with an increased risk of AMD in a study by Van Leeuwen et al. [18] Non neovascular AMD was unrelated to cholesterol level in a study by Hyman et al. [20] No difference in total cholesterol, triglycerides, phospholipids, HDL, LDL concentrations were observed between AMD patients and controls in the study by Abalain et al. [23], and there was no significant difference in the concentration of the Lipoprotein(a) between the AMD and control groups in the work by Nowak et al. [24].

Some correlations between serum lipid and AMD have been made when investigators have looked specifically at high-density lipoproteins. Again, the results have been conflicting. The Rotterdam [18] and Pathologies Oculaires Liees al’Age [27] studies found an association between AMD risk and HDL-C. When separating by disease type, Klein et al. [19] showed that higher serum HDL-C at baseline was associated with pure geographic atrophy or advanced non-neovascular AMD, while Hyman et al. [20] revealed a positive association between HDL level and neovascular, but not non-neovascular AMD and dietary cholesterol level.

On the other hand, different studies have found an inverse correlation with HDL and AMD risk. Reynolds et al. [28] demonstrated that elevated HDL is associated with a reduced risk of advanced AMD, especially the neovascular (NV) subtype and that higher low density lipoprotein (LDL) is associated with increased risk of advanced AMD and the NV subtype. Higher total cholesterol was also associated with AMD risk when controlling for all covariates and genotypes.

These findings were compatible to findings in previous large studies, such as the Blue Mountain Eye Study (BRMES), a population based cohort study, and the Eye Disease Case Control Study (EDCCS). The BRMES found that increased HDL cholesterol was inversely related to incident late AMD. Elevated total/HDL cholesterol ratio predicted late AMD and geographic atrophy [29]. The EDCCS also reported a statistically significant fourfold increased risk of exudative AMD with the highest serum cholesterol levels [25].

The association between the use of cholesterol-lowering medications, including statins, and AMD has also been intensively studied, but results are inconsistent [30–37]. The Rotterdam and several other studies did not find a relationship between cholesterol-lowering medication [30–32] including statins [33] and risk of AMD. McGwin Jr. et al. [34] evaluated the association between the use of cholesterol-lowering medications and AMD in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, a large, prospective, population-based cohort study conducted in four communities across the United States. The large sample size in this study was a strength over previous research on statins and AMD risk. Adjusting for the confounding influence of age, gender, and race, the authors found a significant relationship between AMD and use of cholesterol-lowering medications.

Lipids and Diabetic Retinopathy

Dysfunction of the vascular endothelium is regarded as an important factor in the pathogenesis of diabetic vascular complications and high lipid levels are known to cause endothelial dysfunction due to a reduced bioavailability of nitric oxide. It was also reported that the peroxidation of lipids in lipoproteins in the vascular wall leads to local production of reactive carbonyl species that mediate recruitment of macrophages, cellular activation and proliferation, and also chemical modification of vascular proteins by advanced lipoxidation end products which affect both the structure and function of the vascular wall [38]. Consequently, it was proposed that, hyperlipidemia might contribute to Diabetic Retinopathy and Macular Edema by endothelial dysfunction and breakdown of the blood retinal barrier leading to exudation of serum lipids and lipoproteins [39].

However, there are conflicting reports in the literature regarding the effect of lipid profile on retinopathy or maculopathy. In ETDRS report, Chew et al. [40] stated that patients with high total cholesterol and LDL levels were more likely to have retinal hard exudates compared to patients with normal lipid profile. Moreover, patients with elevated serum total cholesterol, LDL, or triglyceride levels that did not have retinal hard exudate initially, were at increased risk of developing retinal hard exudate during follow up. Other studies showed that retinal exudates or ME was associated either with LDL or total cholesterol, or both [41–43]. In another study, it was reported that lipid profile was not associated with retinal thickness, mild or moderate DME but only clinically significant ME [39].

In the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study, Rema et al. [41] showed that mean cholesterol, triglyceride and non HDL levels were higher in patients with DR compared to those without DR. However, only triglycerides were independently associated with [41]. Similarly, Ebeling and Koivisto reported that duration, age, and triglyceride level explained nearly half of the variation in the severity of retinopathy [44]. Significant associations between DR and total cholesterol was found in patients in Sweden [45].

On the contrary, Ozer et al. [46] could not show a correlation between serum lipid levels and macular edema in diabetic patients. Similarly, Hove et al. [47] reported no significant association between DR, triglycerides, HDL and total cholesterol in diabetic population in Denmark. Miljanovic et al. [48] reported no lipid profile association with progression of DR or with PDR. In another study, there was no association between DR and lipid profile, however, clinically significant ME was found to be associated with serum lipids [39]. Moreover, Singapore Malay Eye study showed that higher cholesterol levels were protective of any retinopathy [49].

Recent data from the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) Study indicated that fenofibrate, a lipid-altering medication, reduced diabetic retinopathy progression and the need for laser treatment in type 2 diabetes [50]. This benefit was unrelated to serum lipid levels, with unclear underlying mechanisms.

It was speculated that serum lipids may have a strong influence only in the severe forms of diabetic microvascular disease. They may not cause direct injury to the endothelium but are rather involved in the pathogenesis of DME only via exudation of lipids through damaged retinal vasculature, which occurs at a later stage. Thus, it was suggested that serum lipids are involved in the later, more severe stages than in earlier stages; as an explanation to the discrepancies among the findings of the studies [39].

Another cause of discrepancy might be ethnicity at least in part. Significant differences in the prevalence of DR and DME between different ethnic groups was reported [51]. Although all ethnic groups are susceptible to the established risk factors of DR such as duration the disease, severity of hyperglycemia and hypertension, ethnicity specific risk factors also may have an effect. Such risk factors may include differential susceptibility to conventional risk factors, insulin resistance, truncal obesity and genetic susceptibility [52]. It may be hypothesized that serum lipid levels may also affect such different populations at a different level, however, this should be supported by further studies.

Lipids and RVOs

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is the second most common retinal vascular disease after diabetic retinopathy. Its pathogenesis is still not completely understood. The condition may be due to a combination of three systemic changes known as Virchow’s triad: (1) hemodynamic changes (venous stasis), (2) degenerative changes of the vessel wall, and (3) blood hypercoagulability [53]. LDL cholesterol, which, like serum globulins and total proteins, clearly contribute to the plasma viscosity. If LDL is increased it may predispose to a hyperviscosity syndrome.

Various studies suggest that 48 % of RVO is connected to hypertension (HTN), 20 % to Hyperlipidemia (HLD), and 5 % to DM [54]. The Diabetes Control and Complications Study (DCCT) and Blue Mountains Study also reported that HTN, HLD, arteriosclerosis, and DM are risk factors for RVO [55, 56]. Schmidt on small sample of patients with RVO in combination with retinal artery occlusion (RAO) described a variety of systemic risk factors. Systemic risk factors were present in 11 out of 14 subjects (mainly HTN 8×, HLD 3×, and chronic smoking 3×) [57].

Lipids and Stargardt Disease

Autosomal recessive Stargardt disease, the most common macular dystrophy, is caused by mutations in the gene encoding ABCA4, a photoreceptor ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter. Biochemical studies [58] together with analysis of ABCA4 knockout mice and Stargardt patients have implicated ABCA4 as a lipid transporter that facilitates the removal of potentially toxic retinal compounds from photoreceptors following photo excitation. An autosomal dominant form of Stargardt disease also known as Stargardt like dystrophy is caused by mutations in a gene encoding ELOVL4, an enzyme that catalyzes the elongation of very long chain fatty acids in photoreceptors and other tissues.

Conclusion

The retina is indeed a unique and enigmatic tissue. Although exquisitely organized for the reception of light, the retina may by damaged easily be exposure to light. The outer segment membranes of the photoreceptor cells contain extremely high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids, yet these constituents are also extremely labile to oxidation. The retina has the highest consumption of oxygen by weight of any tissue and also maintains a prodigious oxygen tension, yet oxygen may be very toxic to the retina. Although the retina possesses certain antioxidant components (e.g. vitamin E, superoxide dismutase, selenium), the levels of glutathione peroxidase and catalase (enzymes which destroy hydrogen peroxide) are relatively low in this tissue [59].

Till date, epidemiologic, molecular & cell biology, and genetic studies have not clearly explained the role of lipids and lipoproteins in various retinal disorders. The contribution of the individual retinal cell types to the overall metabolism of lipids in the retina has not been examined in sufficient detail. Autoradiographic analyses coupled with biochemical techniques should prove extremely useful in such studies. Use of isolated cell preparations for various biochemical studies may be of particular advantage in furthering our knowledge in these areas.

As previously mentioned accumulation of lipoprotein particles in Bruchs’ membrane and their presence within drusen suggests that their deposition is a critical antecedent event in AMD. However, to date studies on the association between serum lipid and AMD risk have been inconsistent. Some correlations between HDL and AMD have been made. Again, the results have been conflicting. It was reported that the peroxidation of lipids in lipoproteins in the vascular wall affect both the structure and function of the blood vessels, which is regarded as an important factor in the pathogenesis of DR. However, there are conflicting reports in the literature regarding the effect of lipid profile on DR. It may be hypothesized that serum lipid levels may affect different populations at a different level, however, this should be supported by further studies. DCCT and Blue Mountains Study reported that hyperlipidemia is a risk factor for RVO. But again no study was able to find correlation between type of lipid and RVO.

It is now necessary for the epidemiologists, and molecular & cellular biologists to work together to figure how lipids influence the pathophysiology of various retinal disorders. It is hoped that greater understanding of the molecular biology will help us to develop multiple treatment targets for the benefit of patients.

Funding

No funding sources.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Gunjan Prakash declares that he has no conflict of interest. Rachit Agrawal declares that he has no conflict of interest. Tanie Natung declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Fliesler SJ, Anderson RE. Chemistry and metabolism of lipids in the vertebrate retina. Prog Lipid Res. 1983;22:79–131. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(83)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Schaft TL, de Bruijn WC, Mooy CM, Ketelaars DA, de Jong PT. Is basal laminar deposit unique for age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:420–425. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080030122052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curcio CA, Millican CL. Basal linear deposit and large drusen are specific for early age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:329–339. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handa JT. New molecular histopathologic insights into the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007;47(1):15–50. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e31802bd546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarks SH, Van Driel D, Maxwell L, Killingsworth M. Softening of drusen and subretinal neovascularization. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1980;100:414–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarks JP, Sarks SH, Killingsworth MC. Evolution of geographic atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Eye. 1988;2:552–577. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarks JP, Sarks SH, Killingsworth MC. Evolution of soft drusen in age-related macular degeneration. Eye. 1994;8:269–283. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Killingsworth MC, Sarks JP, Sarks SH. Macrophages related to Bruch’s membrane in age-related macular degeneration. Eye. 1990;4:613–621. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rungger Brandle E, Englert U, Leuenberger PM. Exocytic clearing of degraded membrane material from pigment epithelial cells in frog retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28:2026–2037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haimovici R, Gantz DL, Rumelt S, Freddo TF, Small DM. The lipid composition of drusen, Bruch’s membrane, and sclera by hot stage polarizing light microscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1592–1599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Clark ME, Crossman DK, Kojima K, Messinger JD, Mobley JA, et al. Abundant lipid and protein components of drusen. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curcio CA, Millican CL, Bailey T, Kruth HS. Accumulation of cholesterol with age in human Bruch’s membrane. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:265–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burns RP, Feeney-Burns L. Clinico-morphologic correlations of drusen of Bruch’s membrane. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1980;78:206–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crabb JW, Miyagi M, Gu X, Shadrach Karen, West KarenA, Sakaguchi Hirokazu, et al. Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14682–14687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222551899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curcio CA, Johnson M, Huang JD, Rudolf M. Aging, age-related macular degeneration, and the response-to-retention of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:393–422. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olofsson SO, Boren J. Apolipoprotein B: a clinically important apolipoprotein which assembles atherogenic lipoproteins and promotes the development of atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 2005;258:395–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lommatzsch A, Hermans P, Müller KD, Bornfeld N, Bird AC, Pauleikhoff D. Are low inflammatory reactions involved in exudative age-related macular degeneration? Morphological and immune histochemical analysis of AMD associated with basal deposits. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:803–810. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0749-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Leeuwen R, Klaver CCW, Vingerling JR, Hofman A, Van Duijn CM, Stricker BH, et al. Cholesterol and age-related macular degeneration: is there a link? Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:750–752. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein R, Klein BE, Tomany SC, Cruickshanks KJ. The association of cardiovascular disease with the long-term incidence of age- related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam eye study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1273–1280. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyman L, Schachat AP, He Q, Leske MC. Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and age-related macular degeneration: age- Related Macular Degeneration Risk Factors Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:351–358. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomany SC, Wang JJ, Van Leeuwen R, Klein R, Mitchell P, Vingerling JR, et al. Risk factors for incident age-related macular degeneration: pooled findings from 3 continents. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1280–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogg RE, Woodside JV, Gilchrist SECM, Graydon R, Fletcher AE, Chan W, et al. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension are strong risk factors for choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1046–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abalain JH, Carre JL, Leglise D, Robinet A, Legall F, Meskar A, et al. Is age-related macular degeneration associated with serum lipoprotein and lipoparticle levels? Clin Chim Acta. 2002;326:97–104. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(02)00288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowak M, Swietochowska E, Marek B, Szapska B, Wielkoszynski T, Kos-Kudla B, et al. Changes in lipid metabolism in women with age-related macular degeneration. Clin Exp Med. 2005;4:183–187. doi: 10.1007/s10238-004-0054-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Risk factors for neovascular age-related macular degeneration The Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:1701–1708. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080240041025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan JSL, Mitchell P, Smith W, Wang JJ. Cardiovascular risk factors and the long-term incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the blue mountains eye study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delcourt C, Michel F, Colvez A, Lacroux A, Delage M, Vernet MH. Associations of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors with age-related macular degeneration: the POLA study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;8:237–249. doi: 10.1076/opep.8.4.237.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds R, Rosner B, Seddon JM. Serum lipid biomarkers and hepatic lipase gene associations with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1989–1995. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheung N, Wong TY. Obesity and eye diseases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:180–195. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein R, Klein BE, Jensen SC, Cruickshanks KJ, Lee KE, Danforth LG, et al. Medication use and the 5-year incidence of early age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dame ye study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1354–1359. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.9.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.VanLeeuwen R, Vingerling JR, Hofman A, DeJong PTVM, Stricker BHC. Cholesterol lowering drugs and risk of age-related maculopathy: prospective cohort study with cumulative exposure measurement. BMJ. 2003;326:255–256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7383.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.VanLeeuwen R, Tomany SC, Wang JJ, Klein R, Mitchell P, Hofman A, et al. Is medication use associated with the incidence of early age-related maculopathy? Pooled findings from 3 continents. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1169–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein R, Klein BE, Tomany SC, Danforth LG, Cruickshanks KJ. Relation of statin use to the 5-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1151–1155. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.8.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGwin G, Jr, Owsley C, Curcio CA, Crain RJ. The association between statin use and age related maculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1121–1125. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.9.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarty CA, Mukesh BN, Guymer RH, Baird PN, Taylor HR. Cholesterol-lowering medications reduce the risk of age- related maculopathy progression. Med J Aust. 2001;175:340. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall NF, Gale CR, Syddall H, Phillips DIW, Martyn CN. Risk of macular degeneration in users of statins: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2001;323:375–376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7309.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarty CA, Mukesh BN, Fu CL, Mitchell P, Wang JJ, Taylor HR. Risk factors for age-related maculopathy: the visual impairment project. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1455–1462. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baynes JW, Thorpe SR. Glycoxidation and lipoxidation in atherogenesis. Free Radical Biol Med. 2000;28:1708–1716. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benarous R, Sasongko MB, Qureshi S, Fenwick E, Dirani M, Wong TY, et al. Differential association of serum lipids with diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:7464–7469. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chew EY. Association of elevated serum lipid levels with retinal hard exudate in diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:1079–1084. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140281004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rema M, Srivastava BK, Anitha B, Deepa R, Mohan V. Association of serum lipids with diabetic retinopathy in urban South Indians—the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES) Eye Study—2. Diabetic Med. 2006;23:1029–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sachdev N, Sahni A. Association of systemic risk factors with the severity of retinal hard exudates in a north Indian population with type 2 diabetes. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:3–6. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.62419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Idiculla J, Nithyanandam S, Joseph M, Mohan VA, Vasu U, Sadiq M. Serum lipids and diabetic retinopathy: a crosssectional study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(Suppl 2):S492–S494. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.104142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ebeling P, Koivisto VA. Occurrence and interrelationships of complications in insulin dependent diabetes in Finland. Acta Diabetol. 1997;34:33–38. doi: 10.1007/s005920050062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larsson L-I, Alm A, Lithner F, Dahlen G, Bergstrom R. The association of hyperlipidemia with retinopathy in diabetic patients aged 15-50 years in the county of Umea. Acta Ophthalmolo Scand. 1999;77(5):585–591. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ozer PA, Unlu N, Demir MN, Hazirolan DO, Acar MA, Duman S. Serum lipid profile in diabetic macular edema. J Diabetes Complicat. 2009;23:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hove MN, Kristensen JK, Lauritzen T, Bek T. The prevalence of retinopathy in an unselected population of type 2 diabetes patients from Arhus County, Denmark. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2004;82:443–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2004.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miljanovic B, Glynn RJ, Nathan DM, Manson JE, Schaumberg DA. A prospective study of serum lipids and risk of diabetic macular edema in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53:2883–2892. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong TY, Cheung N, Tay WT, Wang JJ, Aung T, Saw SM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1869–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keech AC, Mitchell P, Summanen PA, O’Day J, Davis TM, Moffitt MS, et al. Effect of fenofibrate on the need for laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy (FIELD study): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1687–1697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong TY, Klein R, Islam FM, Cotch MF, Folsom AR, Klein BE, et al. Diabetic retinopathy in a multiethnic cohort in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:446–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sivaprasad S, Gupta B, CrosbyNwaobi R, Evans J. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in various ethnic groups: a worldwide perspective. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:347–370. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou JQ, Xu L, Wang S, Wang YX, You QS, Tu Y, et al. The 10-year incidence and risk factors of retinal vein occlusion: the Beijing eye study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ehlers JP, Fekrat S. Retinal vein occlusion: beyond the acute event. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56:281–299. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eye Disease Case Control Study Group Risk factors for central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:545–554. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130537006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mitchell P, Smith W, Chang A. Prevalence and associations of retinal vein occlusion in Australia: the blue mountains eye study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:1243–1247. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140443012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmidt D. Comorbidities in combined retinal artery and vein occlusions. Eur J Med Res. 2013;18:27. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-18-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Molday RobertS, Zhang Kang. Defective lipid transport and biosynthesis in recessive and dominant Stargardt macular degeneration. Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49:476–492. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fliesler SJ, Anderson RE. Chemistry and metabolism of lipids in the vertebrate retina. Prog Lipid Res. 1983;22(2):79–131. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(83)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]