Abstract

Specific immunoglobulin G antibody for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus was detected in maternal blood, umbilical blood, and amniotic fluid from a pregnant SARS patient. Potential protection of fetus from infection was suggested.

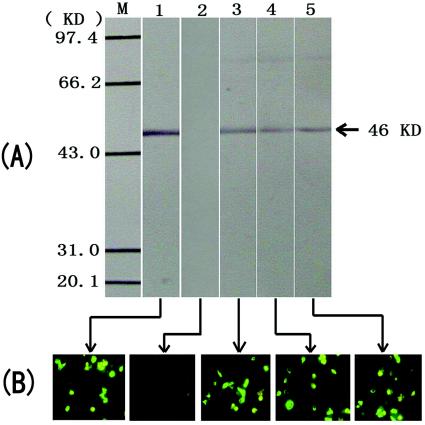

The rapid spread of the coronavirus (CoV) that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) has led to the report of 5,326 probable cases in China alone since 11 June 2003. A female patient at Beijing had asked for an abortion, following recovery from infection with this deadly disease. There was no evidence that indicated that the fetus was also infected. The patient experienced a fever of 39°C on April 13 while in the seventh month of her pregnancy. The patient lived with her husband who had visited his father in the hospital several times after he was diagnosed with SARS on March 10. Her husband contracted a fever on April 11 and was clinically diagnosed as a probable SARS case soon afterwards. The pregnant patient had experienced fever since April 13 and was admitted to Ditan Hospital and diagnosed as a suspected SARS case on April 24. An abortion was performed on May 10, and the specimens of maternal blood, umbilical blood, and amniotic fluid were collected in the surgery with her permission. A high titer of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody against SARS-CoV was observed in both the maternal and umbilical blood samples. The antibody titer was evaluated in series dilution by a SARS IgG detection kit from Huada Biochemical Company (Beijing, China) and indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) against SARS-CoV. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit has been licensed by the State Food and Drug Administration for serological diagnosis for SARS. The kit is based on a plate coated with purified whole virus from culture lysate and labeled anti-human IgG antibodies. It is an indirect ELISA for the detection of SARS-CoV antibodies in human serum or plasma. The mean time to seroconversion was suggested to be 20 days. The serum-specific IgG against CoV was reported to be detected in 70 out of 75 (93%) clinically diagnosed SARS patients 28 days after the onset of the disease (8, 10). The procedure was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Western blotting with purified protein of whole SARS-CoV showed that specific IgG antibody against nucleocapsid (N) protein was also present in maternal blood, umbilical blood, and amniotic fluid (Fig. 1A). The IFA against SARS-CoV was also positive (Fig. 1B). The kit was provided by Euroimmun (Medizinische Labordiagnostika AG, Lübeck, Germany) (slides with SARS virus-infected cells). However, no SARS-CoV genes were detected in either the maternal blood, umbilical blood, or fluid when using a SARS virus fluorescence quantitative PCR diagnostic kit (Da An Gene Co. Ltd. of Zhong Shan University, Guangzhou, China). The specific primers and the fluorescence-labeled probe were designed within the Pol1b gene according to the sequence found at GenBank accession no. AY278741.1. The product size is 85 bp. Each run included positive SARS-CoV genomic template controls (supplied by the manufacturer) to construct a standard curve and a no-template control for the extraction to detect any possible contamination that may have occurred during the processing of samples. Data were analyzed with software provided by the manufacturer (9).

FIG. 1.

Detection of IgG antibody by Western blotting with purified whole-cell proteins of SARS-CoV and by IFA against SARS-CoV in maternal blood, umbilical blood, and amniotic fluid. (A) Western blot. (B) IFA. Lanes: M, molecular standard weight marker of proteins; 1, positive control; 2, negative control; 3, maternal blood; 4, umbilical blood; 5, amniotic fluid. The serum specimens from a clinically diagnosed probable SARS patient and a healthy individual were used as positive and negative controls, respectively, which were confirmed by the methods of ELISA, IFA, and Western blotting.

Human CoVs have been implicated in respiratory infections in hospitalized neonates (3). Some CoVs, such as the mouse hepatitis virus, cause infections which are mild in adult animals but often generate severe and sometimes lethal diseases in neonates (2). The maternal antibodies supplied via the placenta and colostrum efficiently protect newborn animals against the fatal consequences of acute CoV infections during the critical phase of infection. Gustafsson et al. (4) have transferred maternally derived antibody to enterotropic mouse hepatitis virus to pups by both intrauterine (IgG) and lactogenic (IgA and IgG) routes. They observed that the immune mice transmitted equal levels of antibody to three consecutive litters of pups with no evidence of any decline (4). It has also been observed that chicks hatched with high levels of maternal antibody had excellent protection (>95%) against infectious bronchitis virus challenge at 1 day of age (7). Sows naturally infected with transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) exhibited a pronounced decrease in IgG antibody titers to TGEV in the transmission from colostrum to milk. The sows primed with porcine respiratory CoV and boosted with TGEV provided the best passive protection after TGEV challenge exposure of their litter. Not only litter mortality but also morbidity was reduced (6). Our observation suggests that the maternal antibody specific for SARS virus detected in umbilical blood and amniotic fluid has the potential to protect the fetus from infection.

No SARS virus RNA was detected in umbilici fluid, fecal specimens, or mouth-washing saline from the pregnant woman when examined by the SARS virus fluorescence quantitative PCR diagnostic kit. These samples were taken hours before the abortion surgery was performed. It indicated that there is no evidence of transmission of SARS virus through the placental barrier, although the vertical transmission has been observed in mouse hepatitis virus (5). Chen et al. (1) have identified a member of the pregnancy-specific glycoprotein subgroup of the carcinoembryonic antigen gene family that serves as a receptor for mouse hepatitis virus, a murine CoV. However, unlike other pregnancy-specific glycoproteins that are expressed in the placenta, it is expressed predominantly in the brain (1). It is unlikely that pregnant women will be more easily infected by the SARS-CoV than nonpregnant women.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (2003AA208407 to J. Xu) from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen, D. S., M. Asanaka, K. Yokomori, F. Wang, S. B. Hwang, H. P. Li, and M. M. Lai. 1995. A pregnancy-specific glycoprotein is expressed in the brain and serves as a receptor for mouse hepatitis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:12095-12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Groot, A. S. 2003. How the SARS vaccine effort can learn from HIV-speeding towards the future, learning from the past. Vaccine 21:4095-4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagneur, A., J. Sizun, S. Vallet, M. C. Legr, B. Picard, and P. J. Talbot. 2002. Coronavirus-related nosocomial viral respiratory infections in a neonatal and paediatric intensive care unit: a prospective study. J. Hosp. Infect. 51:59-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gustafsson, E., G. Blomqvist, A. Bellman, R. Holmdahl, A. Mattsson, and R. Mattsson. 1996. Maternal antibodies protect immunoglobulin deficient neonatal mice from mouse hepatitis virus (MHV)-associated wasting syndrome. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 36:33-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katami, K., F. Taguchi, M. Nakayama, N. Goto, and K. Fujiwara. 1978. Vertical transmission of mouse hepatitis virus infection in mice. Jpn. J. Exp. Med. 48:481-490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanza, I., D. I. Shoup, and L. J. Saif. 1995. Lactogenic immunity and milk antibody isotypes to transmissible gastroenteritis virus in sows exposed to porcine respiratory coronavirus during pregnancy. Am. J. Vet. Res. 56:739-748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mondal, S. P., and S. A. Naqi. 2001. Maternal antibody to infectious bronchitis virus: its role in protection against infection and development of active immunity to vaccine. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 79:31-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peiris, J. S., S. T. Lai, L. L. Poon, Y. Guan, L. Y. Yam, W. Lim, J. Nicholls, W. K. Yee, W. W. Yan, M. T. Cheung, V. C. Cheng, K. H. Chan, D. N. Tsang, R. W. Yung, T. K. Ng, and K. Y. Yuen. 2003. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 361:1319-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu, X., G. Cheng, B. Di, A. Yin, Y. He, M. Wang, X. Zhou, L. He, K. Luo, and L. Du. 2003. Establishment of a fluorescent polymerase chain reaction method for the detection of the SARS-associated coronavirus and its clinical application. Chin. Med. J. (Engl. Ed.) 116:988-990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu, G., H. Lu, J. Li, Y. Li, Z. Feng, N. Hou, G. Wang, Z. D. Zhao, G. Zhang, C. Yan, H. Li, X. Gao, X. Xu, G. Wang, and H. Zhuang. 2003. Primary investigation on the changing mode of plasma specific IgG antibody in SARS patients and their physicians and nurses. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao 35(Suppl.):23-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]