Abstract

Purpose

Effective targeting of cancer stem cells is necessary and important for eradicating cancer and reducing metastasis-related mortality. Understanding of cancer stemness-related signaling pathways at the molecular level will help control cancer and stop metastasis in the clinic.

Experimental Design

By analyzing microRNA profiles and functions in cancer development, we aimed to identify regulators of breast tumor stemness and metastasis in human xenograft models in vivo and examined their effects on self-renewal and invasion of breast cancer cells in vitro. To discover the direct targets and essential signaling pathways responsible for microRNA functions in breast cancer progression, we performed microarray analysis and target gene prediction in combination with functional studies on candidate genes (overexpression rescues and pheno-copying knockdowns).

Results

In this study, we report that hsa-miR-206 suppresses breast tumor stemness and metastasis by inhibiting both self-renewal and invasion. We identified that among the candidate targets, twinfilin (TWF1) rescues the miR-206 phenotype in invasion by enhancing the actin cytoskeleton dynamics and the activity of the mesenchymal lineage transcription factors, megakaryoblastic leukemia (translocation) 1 (MKL1) and serum response factor (SRF). MKL1 and SRF were further demonstrated to promote the expression of interleukin-11 (IL-11), which is essential for miR-206’s function in inhibiting both invasion and stemness of breast cancer.

Conclusion

The identification of the miR-206/TWF1/MKL1-SRF/IL-11 signaling pathway sheds lights on the understanding of breast cancer initiation and progression, unveils new therapeutic targets, and facilitates innovative drug development to control cancer and block metastasis.

Keywords: microRNA, Twinfilin, MKL1, SRF, interleukin-11, actin cytoskeleton

INTRODUCTION

Cancer stem cells are a subset of cancer cells that are capable of self-renewing and mediating tumor generation and metastasis (1–3). It is necessary and essential to discover and target the stemness regulators of breast cancer, the leading cancer in women, in order to reduce cancer-related mortality. While both genetic and epigenetic alterations regulate cancer stem cell (CSC) functions, we focused on identifying microRNA regulators of breast cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis. MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) are short, non-coding RNAs that have emerged as important posttranscriptional regulators of genes in various cellular processes such as cell growth, motility, invasion, and stress response (4, 5). The major mechanisms by which miRNAs regulate target genes include induction of mRNA degradation and repression of mRNA translation by binding to partial complementary sequences in the 3’ untranslated regions (3’UTRs) (6, 7). Discovery of miRNA-regulated molecular pathways in controlling breast cancer would lead to better understanding of cancer biology as well as future development of novel targeting strategies for the treatment of breast cancer.

Using a forward functional screen on a list of miRNAs differentially expressed in less metastatic tumors, we discovered miR-206 as a suppressor of breast tumor initiation and metastasis. Although miR-206 has been reported in promoting myogenic differentiation (8), its role and signaling in breast cancer stemness were unclear. We sought to identify the role and signaling pathway of miR-206 in stemness-related self-renewal and metastasis-related invasion. Self-renewal is a process of cell division in which at least one daughter cell is identical to the parent cell thereby maintaining the pool of stem cells (2). The gold standard assay of CSC is the tumor regenerating assay in vivo, which is complemented by colony formation or sphere assays in vitro. Mesenchymal features have been implicated in cellular invasion, characterized by cancer cells losing cell-to-cell contacts and migrating away from the cohesive tumor tissue along with altered expression levels of adhesion molecules and cellular skeletons (9, 10). Furthermore, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) enables epithelial cells to adopt a mesenchymal-like morphology along with the formation of actin-rich protrusive and invasive structures, such as invadopodia (11). The question remains whether actin-related cytoskeleton proteins and mesenchymal transcription factors are involved in the miR-206 signaling pathway and EMT regulation.

To fully elucidate the downstream signaling pathway of miR-206, we utilized a global profiling approach to identify the genes inhibited by miR-206. In combination with target gene prediction software and functional rescuing studies, twinfinlin (TWF1 or PTK9) was the top candidate target of the list downregulated by miR-206. The connection of TWF1 function with cell motility and chemotherapy sensitivity was revealed in a systemic RNA interference screening study (12). However, it was unknown whether TWF1 is an essential target of miR-206 and what downstream signaling of TWF1 would regulate stemness. TWF1 is a conserved actin-binding protein with two actin depolymerizing factor homology (ADF-H) domains and belongs to a family of proteins containing the ADF-H domain (13), including cofilin, N-WASP, Arp2/3, and cortactin (14–18). Our previous work demonstrated that TWF1 promotes F-actin (stress fiber) formation as a mesenchymal marker (19, 20). We hypothesized that TWF1 may relay the messages from the actin structures to downstream transcription factors that regulate mesenchymal phenotypes.

Notably, recent breast cancer genomics studies identified susceptibility-related single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located within megakaryoblastic leukemia (translocation) 1 (MKL1) introns (21), implicating a potential relevance of the well-known muscle cell regulator MKL1 in breast cancer development. The transcriptional activity of MKL1, also known as myocardin-related transcription factor (MRTF-A), is regulated by the G-actin monomer concentration and dependent upon binding to and activating serum response factor (SRF) (22, 23). However, the molecular mechanisms by which MKL1 regulates breast cancer progression are unclear. Our work examined whether miR-206 and/or TWF1 signaling pathways were involved in the activation of the mesenchymal lineage transcription factors MKL1/SRF and whether MKL1 and SRF regulate the EMT and invasive phenotype of breast cancer cells. By profiling the self-renewal related cytokines regulated by miR-206, we discovered interleukin-11 (IL-11) as an important effector of miR-206 and further linked it to the MKL1/SRF pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal studies (PDX models and cell line xenografts)

Patient-derived human-in-mouse breast tumor xenograft (PDX) models with spontaneous metastases were generated using patient tumors as described (3). Experiments were performed under the approval of the Institutional Biosafety Committee, Institutional Review Board and the Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care of Case Western Reserve University and the University of Chicago.

Cell culture and transfections

MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, HS578t, and Hek293T were obtained from ATCC or NCI cancer cell line database. Authentication was done by microarray analyses (MDA-MB-231) and phenotypic analyses (MCF-7, HS578t, and Hek293T). Cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin. Cells were transfected with miRNAs (Dharmacon, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; negative control #4) or pooled siRNAs (Dharmacon) at 100nM using Dharmafect (Dharmacon) according to manufacturer’s instructions. 6-hour transfections were repeated twice over consecutive days. TWF1 (as described (19)) Il-11, SRF cDNA vectors (Origene) were transfected using Fugene HD (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions and repeated twice over consecutive days.

Vectors and cloning

A lentiviral gateway vector pFU-attr-PGK-L2G (19) was used to constructed miR-206 expression vector with a precursor entry clone (provided by Dr. Jun Lu at Yale University) using LR clonase II (Invitrogen). Human TWF1 cDNA was subcloned into pDEST40 (Invitrogen) (19). Human G6PD, SRF and IL-11 expression vectors were purchased from Origene. Luciferase vectors containing the 3’UTR of TWF1, G6PD, and Notch were obtained from Switchgear Genomics.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Cell pellets from 6-well plates were dissolved in Trizol and total RNA was extracted using isopropanol and glycogen (Invitrogen). Approximately 1µg RNA per sample was reverse transcribed using qScript SuperMix (Quanta Biosciences). RT-PCR was performed using Taqman primers (Invitrogen) and the relative expressions of the target genes were quantified using the comparative CT method. Mean gene expression levels were normalized to the mean expression levels of the GAPDH reference gene.

Gene expression microarray analyses

Samples were profiled as described previously using oligo microarrays (19) (Agilent Technologies). All microarray data is available in the University of North Carolina (UNC) Microarray Database and have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the accession number GEO-GSE 59751. The log2 transformed expression levels are presented in the supplementary table with paired t Test analyses between miR-206 and other controls in three experiments.

Western blot

Cell were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer (Amresco N653). 20–50 µg of protein samples were loaded and run on mini-PROTEAN 4–20% gradient TGX BIORAD gels. Transferred membraned were blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and probed for antibodies to TWF1 (Genetex GTX11439), MKL1 (Atlas Antibodies) or FAK (Cell Signaling 3285) overnight at 4C. Appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies were incubated for one hour at room temperature for TWF1 and MKL1; and the signals were visualized using LI-COR scanner (LI-COR). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody was used for FAK blotting and incubated for one hour at room temperature and signals were visualized on exposed films.

Cell count analysis

50,000 transfected cells were plated in 24 well plates and harvested every 24 hours over three days. Cells were stained with trypan blue and then counted on hemocytometer. At each time point three wells of cells were counted.

Quantitative invasion assays

Cells were transfected as described earlier except for miR-206 rescue assays where target gene cDNAs were transfected first followed by miR-206 transfection. 100K of cells in triplets were seeded in serum-free DMEM onto matrigel (BD Biosciences) pre-coated transwell inserts (BD Biosciences) with DMEM + 10% FBS in the bottom wells and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Cells were then stained with Calcein AM (BD Biosciences). Cells on the top of inserts were swabbed. Cells on the bottom side of inserts were dissociated in a cell dissociation buffer (Trevigen) shaking for 1 hour at 37°C and the fuorescent signal was measured using a plate reader (Perkin-Elmer).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were transfected twice as stated before and harvested using trypsin. They were washed and re-suspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL in PBS, then re-suspended in 0.3 mL of PBS. To fix the cells, 70% cold ethanol was added dropwise while vortexing gently followed by incubation in ice for at least an hour. Cells were washed twice and re-suspended in 0.25 mL of PBS. 5ul of RNAse A was added (stock concentration 20mg/ml) and incubated by an hour at 37°. After incubation, 10ul of 1mg/ml propidium iodide solution (Sigma) was added. Cells were kept in the dark and at 4° until analysis. Analysis was performed using the BD Accuri flow cytometer. The figure shows multiple reads for an n=1.

Soft agar colony formation assay

For this experiment Agarose was used instead of agar. A 6 well plate was coated at a 1:1 ratio of 1% Agarose and 2× media, solidify for 30 minutes. Top portion was prepared with 0.6% agarose and 2× media with cells plated at a 4,000 cells/mL density. Pictures were taken after 10 days using DeltaVision microscopy.

Annexin V staining

MCF-7 cells were transfected once for 48 hours and collected for analyses. During collection, cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in Annexin V binding buffer (BD) and 5 µl of Annexin V-PE (BD) per manufacturer instructions. Cells were also analyzed using the BD LSR II flow cytometer.

Mammosphere assay

A 24 well plate was coated with poly hema overnight to avoid adherence. Cells were plated at a density of 500 cells per well in serum-free PRIME-XV mammary tumor sphere medium (Irvine Scientific) with 2 U/ml of heparin (Sigma Aldrich) and 0.5µg/mL hydrocortisone (Stem Cell Technologlies). Pictures of mammospheres were taken at 6 days post seeding.

Immunohistochemistry staining

After deparaffinization and rehydration, the tissue sections were incubated in antigen retrieval buffer and heated in steamer at over 97°C for 20 minutes. Anti-TWF1 (PTK9) (Genex, GT111439, rabbit IgG) was applied on tissue sections overnight at 4°C at 1:800 dilution in a humidity chamber. Following TBS wash, the antigen-antibody binding was detected with Envision+ system and DAB+ chromogen (DAKO, K4010). Tissue sections were briefly immersed in hematoxylin for counterstaining, washed with water and covered with cover slips.

Statistical Analysis

For all assays and analyses in vitro, if not specified, student’s t-test was used to evaluate the significant difference or p-values and standard deviations (SD) of mean values were depicted as error bars in figures. For animal studies in vivo, Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to check the normality of the raw data, and MANOVA, ANOVA, or student’s t-test was applied in exploring the P-value and the significant differences between vector and 206 groups. Linear mixed model was fitted to generate the tumor growth graphs with tumor volumes (bioluminescent signals) as response variables, time and each mouse ID as the random effects. The data applied on linear mixed models was derived by taking log transformation of the original tumor volumes. Dot plot was used to represent a comparison of the data distribution in metastatic burden. All the tests and models are performed in R software.

Methods on F-actin quantification, immunofluorescence staining and microscopy, gelatin invadopodia assay, sub-G1 population analysis, luciferase assay, and bioluminescence imaging are provided in supplemental information (SI).

RESULTS

MicroRNA-206 inhibits breast tumorigenesis and metastasis

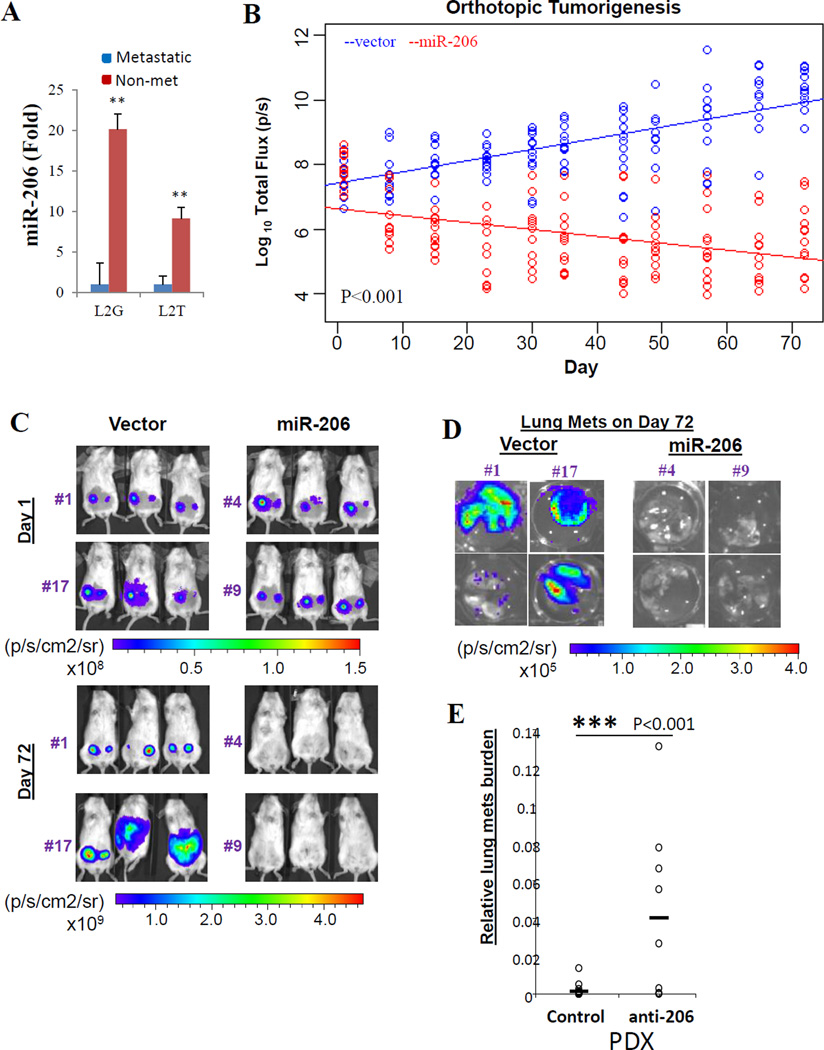

To screen microRNA regulators of breast cancer progression, we previously established patient-derived human-in-mouse breast tumor xenograft (PDX) models in immune-deficient NOD/SCID mice and labeled with Luc2-eGFP (L2G) or Luc2-tdTomato (L2T) (3). Triple negative breast tumor PDXs develop spontaneous lung metastases with altered miRNA expression profiles and differentiation scores (3, 24). Higher miR-206 levels were detected in the relatively non-metastatic tumor cells compared to the metastatic primary tumor cells sorted from L2G and L2T-labeled PDXs (Figure 1A). To investigate the functional significance of miR-206 in breast cancer progression, we modulated miR-206 precursor expression in breast cancer cell lines and PDXs. We first cloned the miR-206 precursor into a gateway lentiviral vector co-expressing the fusion reporter gene L2G, and then generated MDA-MB-231 stable clones overexpressing miR-206 or vector control (backbone). These clones were used to examine the role of miR-206 in both spontaneous metastasis models as well as blood stream-inoculated metastasis models. Compared to the vector controls (clones #1 and #17), orthotopic injection of the miR-206 stable-expression clones (#4 and #9) into the mammary fat pad of NOD-SCID mice resulted in a failure of tumor initiation and progression, as measured by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) of the growth curves over a time course of 72 days (Figure 1B–C). Compared to the empty vector controls, the lungs dissected from the mice bearing miR-206 clones also showed negative bioluminescent tumor signals (Figure 1D). We then inhibited miR-206 function in primary tumor cells isolated from PDXs by transducing its antagonist anti-miR-206. While breast tumor growth did not show significant changes, lung metastasis burden (ratio) based on primary tumor signals significantly increased (Figure 1E), suggesting an inhibitory role of miR-206 in breast cancer progression.

Figure 1. MiR-206 suppresses breast cancer initiation and metastasis in vivo.

A. miR206 expression levels (fold change) in sorted primary breast tumor cells, metastatic (mainly CD44+) and non-metastatic (mainly CD44−) from triple negative patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), measured by Taqman realtime PCR.

B. Log10 plots of bioluminescent signals (total flux, p/s) of mammary tumors versus day, after mammary fat pad injections of L2G vector (blue) or miR-206 overexpressing (red) MDA-MB-231 cells within a time course of 72 days. P values are calculated between linear curves using R software MANOVA.

C. Representative images of mammary tumors on day 1 and day 72, post fat pad injections of L2G vector (left panels: clone #1 and #17) or miR-206 overexpressing (right panels: clone #4 and #9) MDA-MB-231 cells.

D. Representative images of dissected lungs from the mice bearing vector controls (left panels: clone #1 and #17) and miR-206 expressing tumor cells (right panels: clone #4 and #9) on day 72.

Antagonist of miR-206 (anti-206) increased lung metastasis burden of patient-derived breast tumor xenografts (PDXs) while the primary tumor growth was not significantly changed.

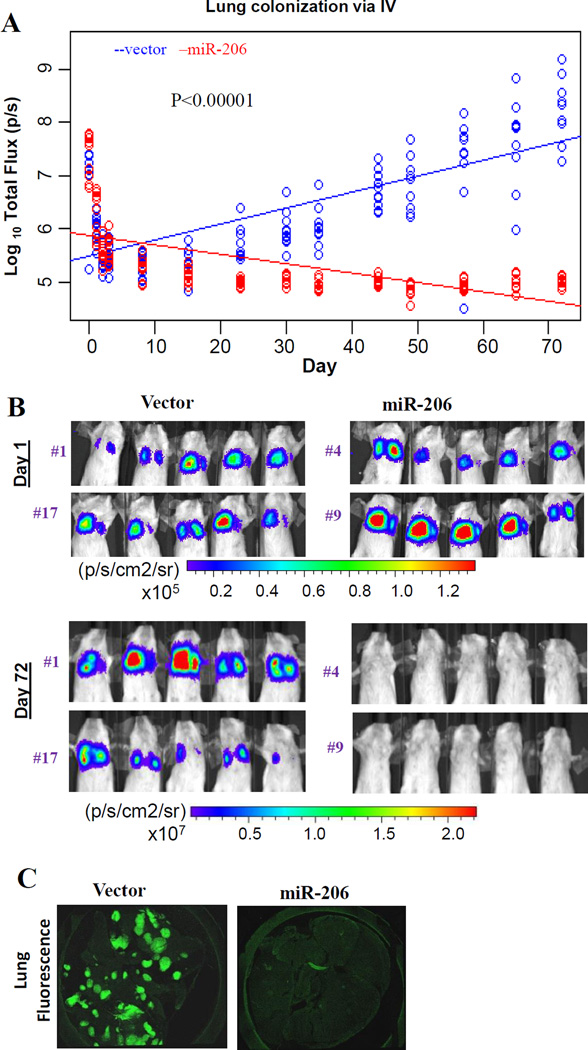

To further evaluate the regulatory effects of miR-206 in lung metastasis, we conducted colonization assays with tail vein injections of the miR-206 stable clones (#4 and #9 clones) or control cells (#1 and #17 clones) into NOD-SCID mice. The miR-206 cells regressed whereas the control cells colonized the lungs with increased bioluminescent tumor metastases (Figure 2A–B). Two-photon imaging of the dissected lungs on day 72 post tail vein injection showed remarkable GFP+ metastases of control cells but an absence of miR-206 overexpression cells in the lungs (Figure 2C). These studies demonstrate the importance of miR-206 in breast cancer initiation and metastasis in vivo.

Figure 2. miR-206 inhibits lung colonization in vivo.

A. Log10 plots on bioluminescent signals (total flux, p/s) of lung micro-metastases versus day within 72 days post tail-vein injections of vector or miR-206 precursor-transduced MDA-MB-231 cells. P values are calculated between linear curves using R software MANOVA.

B. Representative bioluminescent images of lung metastases on day 1 and day 72 post tail-vein injections of the clones from above Figure 1C.

C. Representative confocal microscopy images of mouse lungs dissected from the recipients of miR-206 and vector control cells on day 72 post tail vein injections.

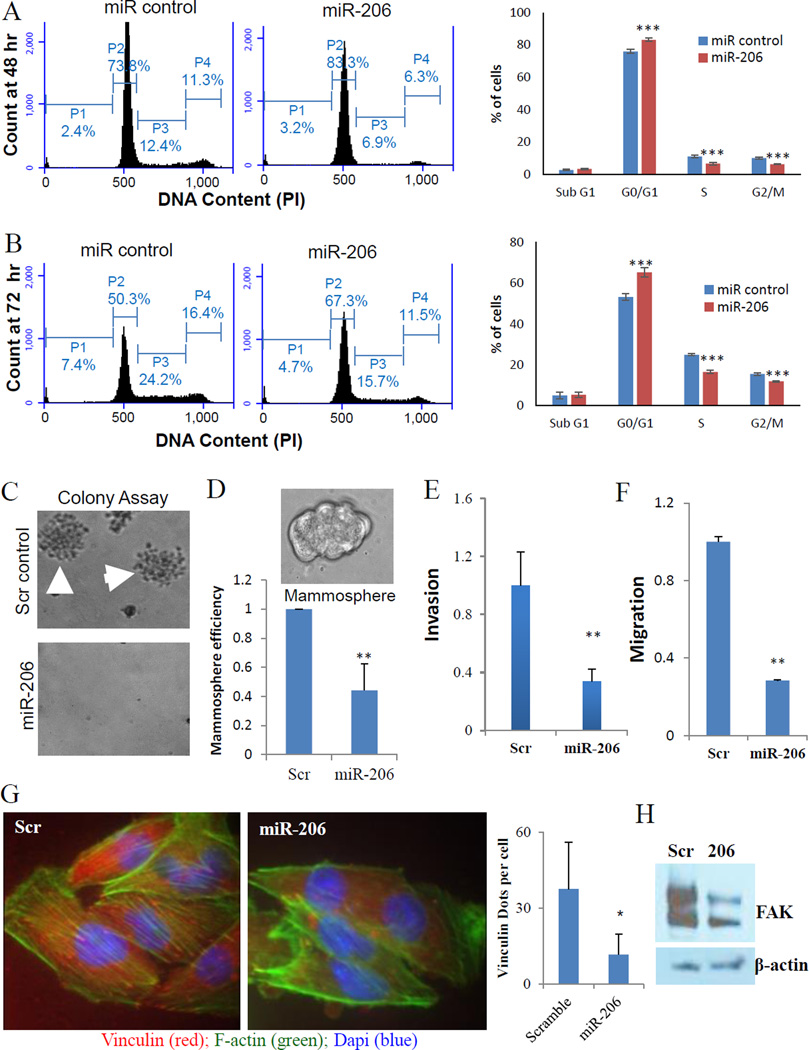

MicroRNA-206 suppresses self-renewal, invasion, and EMT

We continued to examine the effects of transiently transfected miR-206 mimics on cell cycle, self-renewal, invasion, migration, growth, and EMT of triple negative breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231, BT-20, and HS578T) as well as estrogen receptor-positive MCF-7 cells.

We first investigated the role of miR-206 in self-renewal related cell cycle regulation. Shown by DNA content analyses with PI staining, miR-206-transfected MDA-MB-231 cells increased G1 phase population along with decreased S and G2/M phases within 48 hours, and further strengthened the cell cycle arrest at 72 hours post transfection (Figure 3A–B). Furthermore, upregulation of miR-206 in MCF-7 cells caused not only G1 arrest but also additional cell death within 48 hours post transfection, measured by Annexin-V staining (Supplementary Figure 1A–C). By seeding individual tumor cells into solid culture of soft agar or suspension culture with stem cell medium, we demonstrated that miR-206 overexpression abolished the colony formation of MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 3C) and dramatically reduced mammosphere formation efficiency (counts) of MCF-7 cells (Figure 3D). The phenotypic regulation of miR-206 in cell cycle, colony formation, and mammosphere generation in vitro is consistent with its role in inhibiting breast tumor initiation in vivo.

Figure 3. miR-206 induces G1 arrest and inhibits stemness.

A. miR-206 increased G1 phase and decreased S and G2/M populations of MDA-MB-231 cells at 48 hours post transfection. Student t Test P values : ***<0.001.

B. miR-206 increased G1 phase and decreased S populations of MDA-MB-231 cells at 72 hours post transfection. Student t Test P values: ***<0.001.

C. miR-206 abolished MDA-MB-231 single cell-mediated colony formation in soft agar.

D. miR-206 decreased MCF-7 mammosphere formation in serum-free stem cell medium. Student t Test P values: **p<0.001

E. Transwell invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either miR-206 or scramble control. ** p<0.01

F. Vertical transwell migration assays of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either miR-206 or scramble control. **p<0.01

G. Left two panels: representative images (1000×) of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either miR-206 or scramble control; F-actin staining (Phalloidin-green), focal adhesions (Vinculin-red) and DNA (Dapi-blue). Right histogram: quantification of focal adhesions. * p<0.05

H. Decreased FAK protein levels in miR-206 transfected cell lysates compared to that of the scramble control, measured by immunoblotting.

We then examined the effects of miR-206 in metastasis-related cell motility such as cellular invasion and migration using the matrigel-coated transwells (20). Enforced expression of miR-206 significantly reduced invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells, measured by high throughput plate-reader signals of calcein-AM-stained cells that invaded through matrigel, the membrane, and moved to the bottom side of the transwell within 24 hours post plating (Figure 3E). Similarly, miR-206 inhibited the cellular invasion of both BT-20 and HS578T breast cancer cells (Supplementary Figure 2A–B). Elevated levels of miR-206 also suppressed the migration of MDA-MB-231 cells in a 6-hour vertical transwell assay (Figure 3F).

To determine whether the decreased invasion and migration were caused by altered cell growth and proliferation within 24 hours, we performed multiple cell growth analyses, both calcein-AM-based metabolic cell viability staining and cell counts-based growth curve analyses. We first compared the overall cell growth (metabolic) and proliferation (cell count) signals measured by calcein-AM staining which is used in the invasive cell signal quantitation in parallel to trypan blue-based cell counting. With calcein-AM staining, we did not observe a significant effect of miR-206 on the overall cell growth in both MDA-MB-231 and HS578T cells within 24 hours (time point equal to the 24-hour invasion assay or longer than the 6-hour migration assay) (Supplementary Figure 2C–D), indicating that miR-206 mediated inhibition of invasion and migration was due to intrinsic cell motility changes. The cell count-based growth curves revealed that miR-206 started to alter MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation at 72–96 hours (Supplementary Figure 2E) which is consistent with the cell cycle analyses (Figure 3B), whereas in HS578T cells miR-206 slowed down the proliferation rate at early time points without reducing the calcein AM staining signals (Supplementary Figure 2D, 2F). Cell cycle analysis using propidium iodide staining also revealed that at the 24 hour time point, miR-206 caused minimal alterations of MDA-MB-231 cell cycle (G1 and S phase) without detectable sub-G1 pro-apoptotic cell death (Supplementary Figure 2G).

To determine whether miR-206 regulates invasion with an effect on EMT, we chose to evaluate two mesenchymal markers, F-actin and vinculin (19, 24). Notably, elevated miR-206 expression reduced the formation of F-actin stress fibers (green) and vinculin stained focal adhesions (red dots at the end of green fibers) (Figure 3G). We also observed decreased focal adhesion kinase (FAK) levels in miR-206-transfected breast tumor cells (Figure 3H). These results further suggest that miR-206 suppresses EMT by inhibiting actin polymerization and focal adhesion formation.

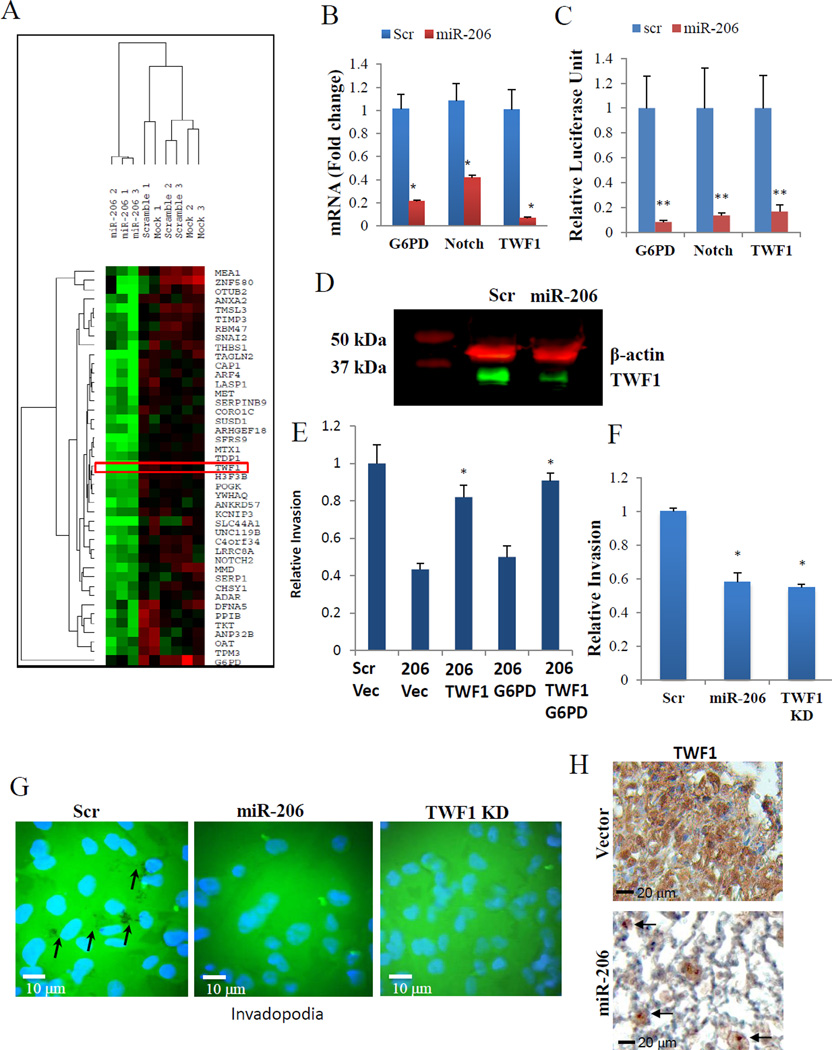

TWF1 is an important target of miR-206

To characterize pathways regulated by miR-206, we analyzed the global transcriptome using microarrays of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with miR-206, scramble, or mock controls. TWF1 was shown on the top of the most downregulated genes by miR-206 (Supplementary Table 1). To focus on the genes directly targeted by miR-206, we used the GeneSet2miR prediction analysis (25), which resulted in 43 potential direct target genes predicted by a minimum of 4 out of 11 established algorithms, as listed in the heat map, including TWF1, NOTCH2, G6PD, and others (Figure 4A, p-value <0.0001). TWF1 regulates both cell morphology and motility through sequestering ADP-actin monomers and capping filament barbed ends (26, 27), Notch2 regulates stem cell population, differentiation, and apoptotic programming (28–30), and Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) relates to glucose metabolism and protection against reactive oxygen species (31). Most importantly, all three of these genes have been shown to regulate cancer progression (19, 29, 32).

Figure 4. TWF1 is an important target of miR-206.

A. Heatmap of 43 candidate targets downregulated in miR-206-transfected MDA-MB-231 cells (n=3) compared to scramble (n=3) and mock-transfected controls (n=3).

B. Realtime PCR of G6PD, Notch2 and TWF1 gene expression in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either miR-206 or scramble control. *p<0.05.

C. Luciferase assays of Hek293T cells co-transfected with luciferase vectors containing 3’UTR of target genes and either miR-206 or scramble control. **p<0.01

D. Western blot of TWF1 (green) in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either miR-206 or scramble control. β-actin (red) was used as a loading control.

E. Transwell invasion assays of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either scramble (Scr) or miR-206 (206) followed by either TWF1 cDNA, G6PD cDNA, both, or pcDNA control (Vec) vectors. *p<0.05

F. Transwell invasion assays of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either miR-206, TWF1 siRNA or scramble control. *p<0.05

G. Representative images of Gelatin Invadopoida Assay 24 hours after MDA-MB-231 cell culture. The black dots in scramble is due to degradation of matrix by localized protrusions of invadopodia, and are absent in miR-206 and TWF1 KD.

H. Immunohistochemistry staining indicates decreased TWF1 in the residual miR-206-transduced breast tumor cells (arrow pointed) compared to the vector control tumor in the lung sections of recipient mice, dissected on Day 72 post tail vein injections (as shown in Fig 2B–C).

To determine whether these genes are real targets of miR-206, we first measured their expression levels upon miR-206 modulation in MDA-MB-231 cells using RT-PCR. Forced expression of miR-206 caused a significant decrease in mRNA levels for NOTCH2, G6PD, and TWF1 compared to the scrambled control (Scr) (Figure 4B). We then set out to determine whether these genes are direct targets of miR-206. By co-transfecting HEK293T cells with miR-206 and the luciferase vector with the 3’UTR of candidate genes cloned downstream of the luciferase gene, we found that miR-206 mediated an inhibitory interaction with the 3’UTR regions of all three candidate genes, thereby reducing the expression levels and activity of the upstream luciferase reporter (Figure 4C). Western blot further showed a decrease in protein levels of TWF1 in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with miR-206 (Figure 4D).

To determine the importance of its target genes in miR-206 mediated functions such as invasion, we performed rescue assays where candidate genes were overexpressed in cells with elevated miR-206 levels. If a gene is an essential downstream player in the miR-206 signaling, overexpression of the gene would reverse miR-206-mediated phenotype. Among three tested candidates, we only observed that TWF1 overexpression was able to prevent or reverse the decreased invasiveness in MDA-MB-231 cells caused by miR-206 (Figure 4E). Other direct targets, such as G6PD, failed to restore the invasiveness of miR-206-overexpressing breast cancer cells back to the control level (Figure 4E). To demonstrate that TWF1 is not only necessary but also sufficient for miR-206 induced phenotype, we knocked down TWF1 in MDA-MB-231 and HS578T cells, which mimicked miR-206 in inhibiting breast cancer cell invasion (Figure 4F and Supplementary Figure 2B). These data indicate that TWF1 is an important and direct target of miR-206 in regulating breast cancer cell invasion. In the subset of clinical breast tumor data set METABRIC (33, 34), we observed a negative correlation between TWF1 and miR-206 expression (Supplementary Table 2), suggesting the clinical relevance of the regulatory role of miR-206 in TWF1 levels in breast tumors.

Cancer cell migration and invasion are dependent upon actin-based cytoskeletal dynamics, such as the formation of stress fibers, focal adhesion, and invadopodia (small localized protrusions that preferentially degrade the matrix). Our data shown in Figure 4D supported that miR-206 inhibits EMT markers of stress fibers (F-actin) and focal adhesion. Our previous studies demonstrated that TWF1 promotes invasion, EMT, F actin formation, and vinculin-stained focal adhesion(19). We further examined the functions of miR-206 and TWF1 in invadopodia formation, which was measured with cells cultured on a fluorescently labeled gel matrix. After 24 hours incubation, MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with scramble controls displayed the invadopodia area (devoid of fluorescence) in the matrix whereas miR-206 overexpressing cells and TWF1 knockdown cells had minimal detectable invadopodia (Figure 4G), indicating the regulatory role of the miR-206/TWF1signaling pathway in the invasiveness related invadopodia. To examine whether miR-206 regulates in TWF1 in breast tumor in vivo, we measured TWF1 protein levels in the lung sections of mice that received MDA-MB-231 cancer cells via tail vein injections. Consistent with Figure 2B–C, in comparison to the L2G vector control cells which regenerated tumors, miR-206 transduced tumor cells did not colonize the lungs where the sparsely distributed single tumor cells had remarkably lower levels of TWF1 (Figure 4H).

Knockdown of TWF1 also mimicked miR-206 upregulation in decreasing cell motility (migration) of MCF-7 cells (Supplementary Figure 2H). However, the downstream signaling of TWF1 was not fully understood, and we decided to seek out mesenchymal regulators related to miR-206/TWF1 functions.

miR-206 and TWF1 regulate MKL1/SRF activities

It has been previously suggested that the mesenchymal lineage transcription factor MKL1 is regulated by G-actin monomers in the cytoplasm which promotes its nuclear export and inhibits its nuclear import (22, 23). This movement of MKL1 outside of the nucleus prevents the activation of the MKL1–SRF (serum response factor) complex in the nucleus that targets many genes encoding cytoskeletal components, including actin (22, 23, 35). We hypothesized that miR206 and TWF1 regulate the mesenchymal phenotype through actin-dynamics and MKL1/SRF signaling.

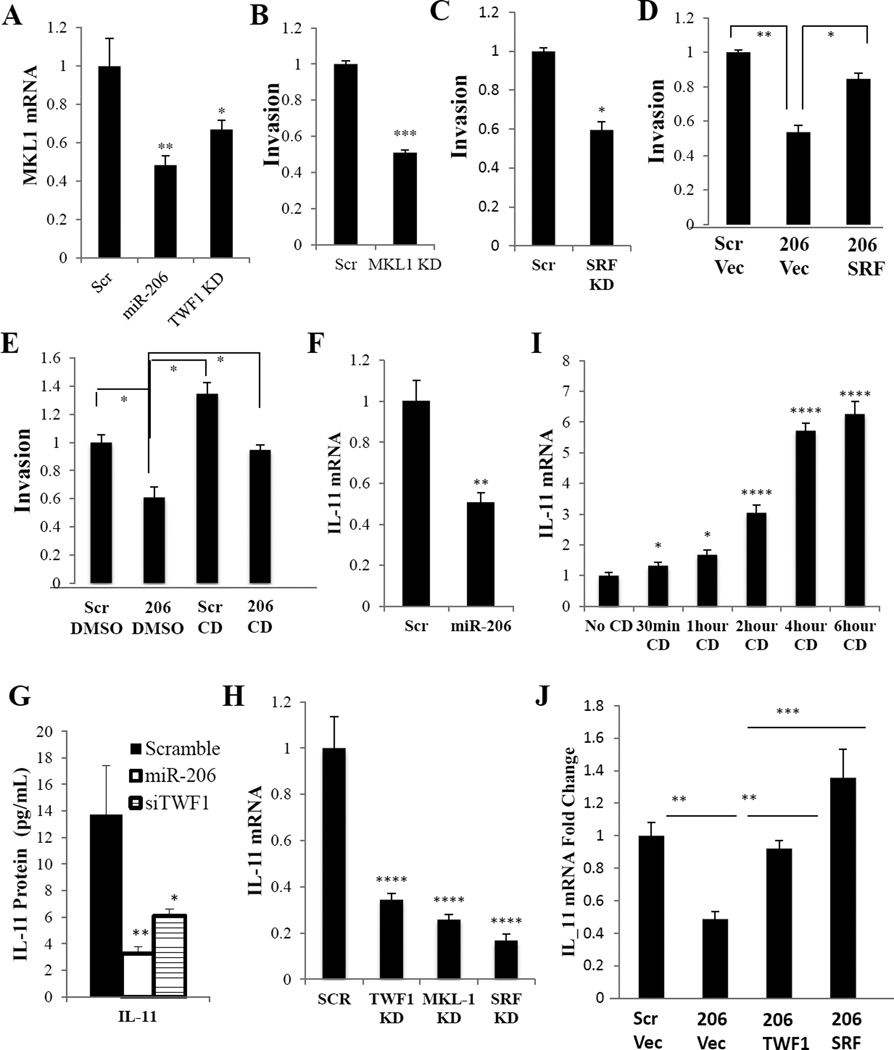

We first investigated the impact of miR-206 on MKL1 mRNA stability and expression levels. Both overexpression of miR-206 and knockdown of TWF1 decreased the mRNA levels of MKL1 (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure 3A). SiRNA-mediated knockdown of either MKL1 or SRF decreased the invasiveness of both MDA-MD-231 and HS578T cells, phenocopying the inhibitory effect of miR-206 overexpression (Figures 5B–C and Supplementary Figure 2B). Furthermore, overexpression of SRF was also sufficient to rescue or restore the invasiveness inhibited by miR-206 in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. miR-206 decreases invasion through regulating MKL1/SRF and IL-11.

A. Realtime PCR of MKL1 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either scramble, miR-206 or TWF1 siRNA. *p<0.05, **p<0.01

B. Transwell invasion assays of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with scramble or MKL1 siRNA. ***p<0.001

C. Transwell invasion assays of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with scramble or SRF siRNA. *p<0.05

D. Transwell invasion assays of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with miR-206 or scramble control followed by a second transfection with either SRF cDNA or pcDNA control vectors. *p<0.05, **p<0.01

E. Transwell invasion assays of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either scramble or miR-206, followed by treatment with either DMSO control or Cytochalasin D (CD). *p<0.05

F. Realtime PCR of IL-11 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with miR-206 or scramble control. **p<0.01

G. IL-11 cytokine assay in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with miR-206, TWF1 siRNA or scramble control. *p<0.05, **p<0.01

H. qPCR of IL-11 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either TWF1, MKL1 or SRF siRNA or scramble control. ****p<0.00001

I. qPCR of IL-11 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with Cytochalasin D (CD) from 30 minutes to 6 hours. *p<0.05, ****p<0.00001

J. qPCR of IL-11 expression levels of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either miR-206 or scramble control followed by either TWF1 cDNA or SRF cDNA or pcDNA control. ****p<0.00001

We then examined the effects of modulated miR-206 and TWF1 levels on actin dynamics, such as the F/G actin ratio in MDA-MB-231 cells. The ratio of F actin to G actin was reduced by miR-206 overexpression or TWF1 knockdown (siRNA-TWF1) (Supplementary Figure 3B). To determine whether miR-206-induced alteration of F/G actin ratio and MKL1/SRF activity regulates invasion, we performed functional rescue assays by using cytochalasin D (CD) to promote MKL1 translocation and SFR activity. As reported, MKL1 is a cytoplasmic protein trapped by G-actin, and its release from G-actin results in its translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus where it binds to SRF as a coactivator (36). CD has a high affinity to G-actin so it releases MKL1 from its G-actin trap and thereby triggers MKL1 translocation and SRF activation (36). Relative to the DMSO vehicle control, CD itself promoted cellular invasion and reversed the inhibitory effects of miR-206 on invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 5E). That is consistent with the functional rescuing effects of SRF in reversing the miR-206 phenotype in invasiveness of breast cancer cells (Figure 5D).

miR-206 and TWF1 regulate IL-11 expression

Interleukin 6 family members, such as leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and interleukin 11 (IL-11) are known to regulate STAT3 activity and self-renewal of embryonic stem cells (37, 38). We previously reported that IL-11 promotes EMT and chemo-resistance in breast cancer (19). We examined the relevance of these cytokines in the miR-206-mediated signaling pathway. We found that compared to the scramble control, miR-206 mediated a reduction of IL-11 at both mRNA and protein levels in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figures 5F–G). Furthermore, TWF1 siRNA also reduced the IL-11 mRNA and/or protein levels in multiple breast cancer cells (Figures 5G–H and Supplementary Figure 3C).

We also determined the effects of MKL1-SRF transcription complex on IL-11 expression. Similar to the inhibitory effects of miR-206 and siTWF1, knockdown of MKL1 or SRF decreased IL-11 expression in MDA-MB-231 and HS578T cells (Figure 5H and Supplementary Figure 3C). We then examined the effects of altered activity of MKL1 and SRF on IL-11 expression. Within 30 mins to 6 hours, the treatment with the MKL1 activator CD resulted in a rapid time-dependent increase of the IL-11 mRNA levels in both MDA-MB-231 and HS578T cells as measured by real-time PCR (Figure 5I and Supplementary Figure 3D), suggesting a quick, likely direct, transcriptional control of IL-11 by activated MKL-SRF. More importantly, functional rescuing studies further demonstrated that both TWF1 and SRF are able to restore the IL-11 expression suppressed by miR-206 (Figure 5J), suggesting that TWF1 and MKL1/SRF are essential downstream players of miR-206 in regulating IL-11.

Since there was a report that estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) regulates miR-206 expression in ER-positive breast cancer (39), we sought to determine whether miR-206 induces a similar signaling pathway in ER-positive cells. RT-PCR results also demonstrated that in MCF7 cells miR-206 overexpression led to a comparable reduction of TWF1, MKL1, and IL-11 expression levels and signaling from TWF1 to MKL1 and IL-11 as in other breast cancer cells (Supplementary Figure 3E). These observations suggest that miR-206 regulation of breast cancer cell phenotypes through targeting TWF1 pathway is independent of ER status.

The next task was to determine the importance of IL-11 in miR-206 signaling pathway and its function in breast cancer.

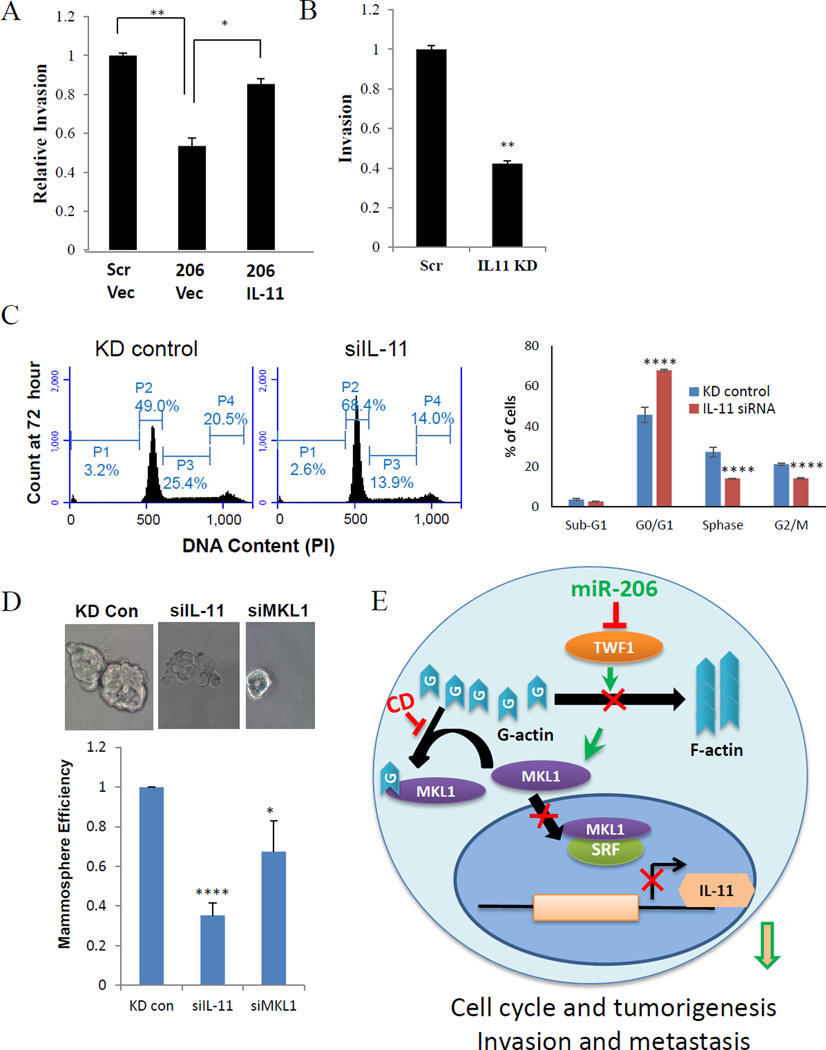

IL-11 promotes invasion and self-renewal of breast cancer cells

We decide to perform functional rescue studies to evaluate the role of IL-11 in miR-206 phenotype regulation. Using transwell invasion assays, we observed that IL-11 overexpression reversed the inhibitory effect of miR-206 on invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 6A). Furthermore, IL-11 siRNAs transfected in MDA-MB-231 and HS578T cells pheno-copied miR-206 in inhibiting cell invasion (Figure 6B and Supplementary Figure 2B). These findings show IL-11 is an important downstream target of miR-206 and TWF1 in regulating breast cancer invasion and metastasis.

Figure 6. IL-11 promotes invasion, cell cycle and self-renewal.

A. Transwell invasion assays of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either scramble or miR-206 followed by either IL-11 cDNA or pCDNA control vectors. *p<0.05, **p<0.01

B. Transwell invasion assays of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either IL-11 siRNA or scramble control. **p<0.01

C. siIL-11 significantly increased G1 phase and decreased S and G2/M populations of MDA-MB-231 cells at 72 hours post transfection. Student t Test P values: **<0.01, ***<0.001, ****<0.00001.

D. siIL-11 decreased MCF-7 mammosphere formation in serum-free stem cell medium. Student t Test P values: ****p<0.00001

E. Diagram of miR-206/TWF1/MKL1-SRF/IL-11 signaling in breast cancer cells. Mechanism proposed for miR-206 regulation in triple negative breast tumors. Higher levels of miR-206 reduces TWF1 and somewhat reduced MKL1 expression. Reduction of TWF1 leads to more free G-actin, which binds to left over MKL1 preventing its translocation into the nucleus and its subsequent activation of SRF. A reduction of SRF activity leads to lower levels of IL-11 mRNA and protein expression.

We then continued to examine whether IL-11 regulates cell cycle and self-renewal of breast cancer cells. Within 72 hours, IL-11 knockdown induced a significant increase of MDA-MB-231 cells at G1 phase arrest along with decreased cell populations in S and G2/M phases, reminiscent of the cell cycle regulatory effects of miR-206 (Figure 6C). Consistently, knockdown of IL-11 or MKL-1 also mimicked miR-206 and remarkably reduced the mammasphere formation efficiency (both number and size) in MCF-7 mammary tumor cells (Figure 6D), implicating that the MKL1/IL-11 signaling pathway is essential for miR-206 function in regulating breast tumor self-renewal and tumorigenesis. We also observed that both miR-206 upregulation and IL-11 knockdown reduced the CD44 expression that is a marker of cancer stem cells in breast cancer (Supplementary Figure 4A–B)

Overall our data report a novel signaling pathway mediated by miR-206 that targets TWF1, MKL1 and SRF, and subsequently IL-11 expression, thereby inhibiting cell cycle and self-renewal in tumorigenesis as well as cell motility (EMT, migration, invadopodia formation, and invasion) in breast cancer metastasis (Figure 6E). High levels of miR-206 reduce TWF1 expression that not only causes high free G-actin to trap MKL1 in the cytoplasm and reduce its transcriptional activity along with SRF, but also reduces its expression levels. Reduced MKL1/SRF activity leads to lower levels of IL-11 mRNA and protein, which are required for both breast cancer initiation and metastasis.

DISCUSSION

Although miR-206 has been shown to play a role in tumor regulation (8, 40–42), our studies uncovered a novel signaling cascade mediated by miR-206, TWF1, MKL1/ SRF, and IL-11 in breast cancer stemness and invasion, relevant to breast tumor regeneration and metastasis. Many of the components are potential new targets for breast cancer therapeutics, including both miR-206 and the siRNAs of its target genes. TWF1 has been reported to regulate cell cytoskeleton and motility through direct interactions with actin filaments (27, 43). Although cofilin, profilin, and other regulators of actin dynamics are well known to regulate cancer cells, the role and signaling pathways of TWF1 in cellular invasion and stemness were underappreciated. Our studies here comprehensively link TWF1 to both upstream miRNA regulators (miR-206) and downstream protein players, including transcription factor complex (MKL1/SRF) and cytokines (IL-11), demonstrating that TWF is central to miRNA functions in breast cancer development and progression.

While MKL1 and SRF are relatively known for their role in transcriptionally regulating cardiovascular growth and muscle cell differentiation (44), our studies link the mesenchymal muscle lineage transcription factors with breast cancer progression. Our data highlight the importance of the G-actin/F-actin dynamics and related MKL1/SRF activity in regulating stemness, invasion, and miRNA/TWF1/IL-11 signaling. Along with the other two coactivators, myocardin and MRTF-B, MKL1 (or called MRTF-A) is one of the three major co-activators of the transcription factor SRF (21, 22). Compared to the knockout mice of other SRF coactivators, MKL1−/− mice possess a unique phenotype of deficient mammary myoepithelial cells and premature involution during pregnancy and lactation (44, 45). Nevertheless, our work suggests that MKL1 may be the major regulator of SRF in the dissected miR-206 signaling pathway in breast cancer cells. These are consistent with the evidence reporting a breast cancer risk susceptibility variation within the MKL1 gene (21) as well as its regulatory role in cytoskeletal dynamics and cell motility in a Rho kinase-dependent manner (44, 46). The direct or indirect regulation nature of IL-11 by SRF remains to be elucidated. The immediate response of IL-11 mRNA upregulation within 30 mins upon MKL1 activation may suggest a direct regulation. Many SRF target genes control cytoskeletal components including actin, and the SRF−/− cells have defects in adhesion and migration (35, 47, 48).

As an IL-6 family member, IL-11 is a cytokine that enhances platelet production (49), and its recombinant protein (oprelvekin) has been used as an approved drug to treat cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and to prevent thrombocytopenia (50). Our report here, however, confirms an oncogenic role of IL-11 in promoting stemness and cancer invasion, consistent with our previous studies demonstrating the association of IL-11 with poor clinical outcome including relapse-free survival in breast cancer patients (19). This also raises questions about the current clinical applications of IL-11 in cancer patients and calls for a careful re-evaluation of its benefits and potential cancer-promoting effects in the clinical setting.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Metastasis accounts for 90% of breast cancer mortality and demands better strategies for its understanding and treatment. Cancer stem cells have been reported to mediate metastasis and resist conventional therapies, thus being considered the root of cancer and the seeds of metastasis. To stop cancer regeneration and metastasis requires effective targeting of cancer stem cells using innovative approaches against both stemness and invasion. We discovered that miR-206 inhibits both self-renewal and invasion through suppressing expression and/or activities of the cytoskeleton gene TWF1, mesenchymal transcription factors MKL1/SRF, and subsequent cytokine IL-11 in breast cancer cells. The newly identified miR-206/MKL1/IL-11 signaling pathway in regulation of breast cancer stemness provides new therapeutic targets and facilitates miRNA/siRNA-based drug development, thereby potentially impacting cancer treatment and preventing/blocking metastasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratories of Dr. Geoffrey Greene (The University of Chicago), Dr. Charles M. Perou (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), and Dr. Jun Lu (Yale University) for technical support to the project. Dr. Jun Lu provided the miRNA entry clones and the gateway vector backbone. We appreciate the experimental support of several core facilities, including animal facility, optical imaging core facility, integrated microscopy core facility (or the cytometry & imaging microscopy Core), and DNA sequencing facility at the University of Chicago and/or Case Western Reserve University. This study was supported in part by Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program W81XWH-09-1-0331 and W81XWH-16-1-0021, Paul Calabresi K12 Award 1K12CA139160-02, the University of Chicago Cancer Center Support Grant CA 014599, Case Western Reserve University start-up fund, NIH/NCI K99/R00 CA160638-02, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center Pilot Project P30 CA043703-23, American Cancer Society ACS127951-RSG-15-025-01-CSM, Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation CCR15332826, Ohio Cancer Research Associates Seeding Grant, Northern Ohio Golf Charities & Foundation, and Case Comprehensive Cancer Center VelaSano Bike for Cure Pilot grant (to H.L.).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: There is no conflict of interest for the authors of this manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.S., V.A., J.B., Y-F.C., S.H., A.P., R.D., Y.W., G.Y.W., N.H., and H.L. designed and performed experiments, and analyzed data. G.K., D.H. and H.Z. performed biostatistical analyses for animal work and association studies. R.S, V.A., J.B., S.H., and H.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adorno-Cruz V, Kibria G, Liu X, Doherty M, Junk DJ, Guan D, et al. Cancer stem cells: targeting the roots of cancer, seeds of metastasis, and sources of therapy resistance. Cancer research. 2015;75:924–929. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu H, Patel MR, Prescher JA, Patsialou A, Qian D, Lin J, et al. Cancer stem cells from human breast tumors are involved in spontaneous metastases in orthotopic mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18115–18120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006732107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, et al. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435:828–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng Y, Yi R, Cullen BR. MicroRNAs and small interfering RNAs can inhibit mRNA expression by similar mechanisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:9779–9784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630797100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutvagner G, Zamore PD. A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science. 2002;297:2056–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1073827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taulli R, Bersani F, Foglizzo V, Linari A, Vigna E, Ladanyi M, et al. The muscle-specific microRNA miR-206 blocks human rhabdomyosarcoma growth in xenotransplanted mice by promoting myogenic differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2366–2378. doi: 10.1172/JCI38075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:1420–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nature reviews. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machesky LM. Lamellipodia and filopodia in metastasis and invasion. FEBS letters. 2008;582:2102–2111. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meacham CE, Ho EE, Dubrovsky E, Gertler FB, Hemann MT. In vivo RNAi screening identifies regulators of actin dynamics as key determinants of lymphoma progression. Nature genetics. 2009;41:1133–1137. doi: 10.1038/ng.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ojala PJ, Paavilainen VO, Vartiainen MK, Tuma R, Weeds AG, Lappalainen P. The two ADF-H domains of twinfilin play functionally distinct roles in interactions with actin monomers. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3811–3821. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gligorijevic B, Wyckoff J, Yamaguchi H, Wang Y, Roussos ET, Condeelis J. N-WASP-mediated invadopodium formation is involved in intravasation and lung metastasis of mammary tumors. Journal of cell science. 2012;125:724–734. doi: 10.1242/jcs.092726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin TA, Pereira G, Watkins G, Mansel RE, Jiang WG. N-WASP is a putative tumour suppressor in breast cancer cells, in vitro and in vivo, and is associated with clinical outcome in patients with breast cancer. Clinical & experimental metastasis. 2008;25:97–108. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yokotsuka M, Iwaya K, Saito T, Pandiella A, Tsuboi R, Kohno N, et al. Overexpression of HER2 signaling to WAVE2-Arp2/3 complex activates MMP-independent migration in breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2011;126:311–318. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang W, Eddy R, Condeelis J. The cofilin pathway in breast cancer invasion and metastasis. Nature reviews Cancer. 2007;7:429–440. doi: 10.1038/nrc2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Tondravi M, Liu J, Smith E, Haudenschild CC, Kaczmarek M, et al. Cortactin potentiates bone metastasis of breast cancer cells. Cancer research. 2001;61:6906–6911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bockhorn J, Dalton R, Nwachukwu C, Huang S, Prat A, Yee K, et al. MicroRNA-30c inhibits human breast tumour chemotherapy resistance by regulating TWF1 and IL-11. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1393. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bockhorn J, Yee K, Chang YF, Prat A, Huo D, Nwachukwu C, et al. MicroRNA-30c targets cytoskeleton genes involved in breast cancer cell invasion. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:373–382. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2346-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michailidou K, Hall P, Gonzalez-Neira A, Ghoussaini M, Dennis J, Milne RL, et al. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nature genetics. 2013;45:353–361. 61e1–61e2. doi: 10.1038/ng.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miralles F, Posern G, Zaromytidou AI, Treisman R. Actin dynamics control SRF activity by regulation of its coactivator MAL. Cell. 2003;113:329–342. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vartiainen MK, Guettler S, Larijani B, Treisman R. Nuclear actin regulates dynamic subcellular localization and activity of the SRF cofactor MAL. Science (New York, NY. 2007;316:1749–1752. doi: 10.1126/science.1141084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bockhorn J, Prat A, Chang Y-F, Liu X, Huang S, Shang M, et al. Differentiation and loss of malignancy of spontaneous pulmonary metastases in patient-derived breast cancer models (PDXs) Cancer research. 2014 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1188. (accepted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonov AV, Dietmann S, Wong P, Lutter D, Mewes HW. GeneSet2miRNA: finding the signature of cooperative miRNA activities in the gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W323–W328. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poukkula M, Kremneva E, Serlachius M, Lappalainen P. Actin-depolymerizing factor homology domain: a conserved fold performing diverse roles in cytoskeletal dynamics. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2011;68:471–490. doi: 10.1002/cm.20530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helfer E, Nevalainen EM, Naumanen P, Romero S, Didry D, Pantaloni D, et al. Mammalian twinfilin sequesters ADP-G-actin and caps filament barbed ends: implications in motility. EMBO J. 2006;25:1184–1195. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazur PK, Einwachter H, Lee M, Sipos B, Nakhai H, Rad R, et al. Notch2 is required for progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:13438–13443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002423107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parr C, Watkins G, Jiang WG. The possible correlation of Notch-1 and Notch-2 with clinical outcome and tumour clinicopathological parameters in human breast cancer. International journal of molecular medicine. 2004;14:779–786. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.14.5.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiuza UM, Arias AM. Cell and molecular biology of Notch. The Journal of endocrinology. 2007;194:459–474. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leopold JA, Cap A, Scribner AW, Stanton RC, Loscalzo J. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency promotes endothelial oxidant stress and decreases endothelial nitric oxide bioavailability. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2001;15:1771–1773. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0893fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang P, Du W, Wang X, Mancuso A, Gao X, Wu M, et al. p53 regulates biosynthesis through direct inactivation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:310–316. doi: 10.1038/ncb2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, Turashvili G, Rueda OM, Dunning MJ, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486:346–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dvinge H, Git A, Graf S, Salmon-Divon M, Curtis C, Sottoriva A, et al. The shaping and functional consequences of the microRNA landscape in breast cancer. Nature. 2013;497:378–382. doi: 10.1038/nature12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Q, Chen G, Streb JW, Long X, Yang Y, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, et al. Defining the mammalian CArGome. Genome research. 2006;16:197–207. doi: 10.1101/gr.4108706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper JA. Effects of cytochalasin and phalloidin on actin. The Journal of cell biology. 1987;105:1473–1478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.4.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirai H, Karian P, Kikyo N. Regulation of embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency by leukaemia inhibitory factor. The Biochemical journal. 2011;438:11–23. doi: 10.1042/BJ20102152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niwa H, Burdon T, Chambers I, Smith A. Self-renewal of pluripotent embryonic stem cells is mediated via activation of STAT3. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2048–2060. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kondo N, Toyama T, Sugiura H, Fujii Y, Yamashita H. miR-206 expression is down-regulated in estrogen receptor alpha-positive human breast cancer. Cancer research. 2008;68:5004–5008. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun C, Liu Z, Li S, Yang C, Xue R, Xi Y, et al. Down-regulation of c-Met and Bcl2 by microRNA-206, activates apoptosis, and inhibits tumor cell proliferation, migration and colony formation. Oncotarget. 2015;6:25533–25574. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen QY, Jiao DM, Wu YQ, Chen J, Wang J, Tang XL, et al. MiR-206 inhibits HGF-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer via c-Met /PI3k/ Akt/mTOR pathway. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin K, Yin W, Wang Y, Zhou L, Liu Y, Yang G, et al. MiR-206 suppresses epithelial mesenchymal transition by targeting TGF-beta signaling in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paavilainen VO, Hellman M, Helfer E, Bovellan M, Annila A, Carlier MF, et al. Structural basis and evolutionary origin of actin filament capping by twinfilin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3113–3118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608725104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parmacek MS. Myocardin-related transcription factors: critical coactivators regulating cardiovascular development and adaptation. Circulation research. 2007;100:633–644. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259563.61091.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun Y, Boyd K, Xu W, Ma J, Jackson CW, Fu A, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia-associated Mkl1 (Mrtf-a) is a key regulator of mammary gland function. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5809–5826. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Medjkane S, Perez-Sanchez C, Gaggioli C, Sahai E, Treisman R. Myocardin-related transcription factors and SRF are required for cytoskeletal dynamics and experimental metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:257–268. doi: 10.1038/ncb1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alberti S, Krause SM, Kretz O, Philippar U, Lemberger T, Casanova E, et al. Neuronal migration in the murine rostral migratory stream requires serum response factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:6148–6153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501191102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schratt G, Philippar U, Berger J, Schwarz H, Heidenreich O, Nordheim A. Serum response factor is crucial for actin cytoskeletal organization and focal adhesion assembly in embryonic stem cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;156:737–750. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paul SR, Bennett F, Calvetti JA, Kelleher K, Wood CR, O'Hara RM, Jr, et al. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding interleukin 11, a stromal cell-derived lymphopoietic and hematopoietic cytokine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7512–7516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tepler I, Elias L, Smith JW, 2nd, Hussein M, Rosen G, Chang AY, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of recombinant human interleukin-11 in cancer patients with severe thrombocytopenia due to chemotherapy. Blood. 1996;87:3607–3614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.