Abstract

A mass-spring-damper model may serve as an extension of biomechanical data from three-dimensional motion analysis and epidemiological data which help to delineate populations at-risk for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. The purpose of this study was to evaluate such a model.

Thirty-six ACL reconstruction (ACLR) group subjects and 67 controls (CTRL) completed single-leg drop landing and single-leg broad jump tasks. Landing ground reaction force data were collected and analyzed with a mass-spring damper model. Medians, interquartile ranges, and limb symmetry indices were calculated and comparisons were made within and between groups.

During a single-leg drop landing, the ACLR group had a lower spring LSI than the CTRL group (P = 0.015) and landed with decreased stiffness in the involved limb relative to the uninvolved limb (P = 0.021). The ACLR group also had an increased damping LSI relative to the CTRL group (P = 0.045). The ACLR subjects landed with increased stiffness (P = 0.006) and decreased damping (P = 0.003) in their involved limbs compared to CTRL subjects non-dominant limbs. During a single-leg forward broad jump, the ACLR group had a greater spring LSI value than the CTRL group (P = 0.045). The CTRL group also recorded decreased damping values on their non-dominant limbs compared to the involved limbs of the ACLR group (P = 0.046).

Athletes who have undergone ACLR display different lower limb dynamics than healthy controls according to a mass-spring damper model. Quadriceps dominance and leg dominance are components of ACLR athletes’ landing strategies and may be identified with a mass-spring-damper model and addressed during rehabilitation.

Keywords: anterior cruciate ligament, athletes, injury prevention

INTRODUCTION

Injury to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) of the knee is a common sports injury that can lead to physical and emotional impairments in the short term and has a high potential to progress to permanently reduced athletic participation in the long term.(49) Athletes are generally counseled that reconstructive surgery is necessary for return to full pre-injury activities.(38) Unfortunately, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) does not guarantee a return to previous levels of activity, high level knee function, or future joint preservation.(35) Moreover, for those who do resume their previous level of activity, the risk of a second ACL injury may be as high as 29%.(56) The risk can be associated with several factors like the type of graft,(7, 22, 37) level of sports,(30, 61, 63) sex,(8, 55, 56) age,(1, 3, 6, 15, 29, 31, 34, 36, 60, 63) time since surgery,(59) and biomechanical adaptations during dynamic tasks.(57) Although several of these factors are non-modifiable, the biomechanical components of second ACL injury risk may be effectively addressed with targeted neuromuscular training prior to unrestricted sports participation.(12) Hence, studies of lower extremity biomechanics are becoming more prevalent as researchers strive to further understand the complexities of lower extremity mechanical risk factors after ACLR.(14, 20, 44, 65)

In particular, stiffness has gained interest in relation to lower extremity injuries.(9) A single-leg hop task performed by a cohort of patients after ACLR revealed significant inter-limb differences in that the involved leg had reduced ability to absorb vertical ground reaction forces (VGRF).(44) In its simplest sense, stiffness is the relationship between the deformation of a body and a given force. While some stiffness may be necessary for performance, either too much or too little stiffness may lead to injury.(9)

In terms of the human body, stiffness may be examined with a variety of methodology from the muscle fiber level, to modeling the entire body as a mass and spring.(9) There are two popular approaches to the modeling of the musculoskeletal system, namely musculoskeletal modeling or a mass-spring-damper (MSD) modeling approach.(51) In the latter approach, a number of masses represent the inertial properties of body segments, accounting for both hard and soft tissues. The mechanical properties of the various body segments, including bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments, are represented in the model by springs and dampers.(52) A typical MSD model has much fewer elements than a typical musculoskeletal system model, as tissues in MSD models are grouped together as one element of the model. Due to the limited number of elements, MSD models may be easier to utilize and interpret than musculoskeletal models.(52) The other advantage of this model is that in vivo biomechanical data can be used as input for dynamic models to analyze movements. This model requires certain assumptions with regards to material properties and anatomy.(58) Nonetheless, a MSD model may serve as an extension of coupled biomechanical–epidemiological motion analysis data to relate vertical ground reaction forces (VGRF) and external loading conditions to ACL strains.(58) The addition of MSD model data to biomechanical data traditionally utilized to estimate ACL injury risk, such as the landing knee abduction moment during a drop vertical jump maneuver, may enhance pre-participation screening of athletes. Clinicians utilizing an MSD model may consider limb stiffness symmetry in addition to more commonly used measures during screening in order to identify a greater number of athletes with biomechanical asymmetries. These athletes may then be enrolled in neuromuscular training protocols and their progress continually monitored with the same biomechanical measurements in order to reduce risk of injury during play.

This prospective cohort biomechanical study and technical report utilized a novel MSD model to determine the lower limb kinetics during single-limb landing in a group of patients who had undergone ACLR and returned to play compared with those in a healthy control group (CTRL). The following were hypothesized:

The ACLR group would display different lower limb landing kinetics as measured by limb symmetry indices for both spring and damping values compared to a healthy, uninjured CTRL group.

The ACLR group would display different lower limb landing kinetics as measured by limb symmetry indices for the spring value in the reconstructed limb compared with their contralateral limb.

METHODS

Experimental Approach to the Problem

Biomechanical data were collected during single leg drop landing and single leg broad jump tasks. A generalized cross-validation spline was used to filter raw VGRF data at a 50-Hz cutoff frequency. Peak VGRF during the first 250 ms (landing phase) was calculated for each trial. Maximum VGRF was divided by potential energy to calculate normalized VGRF (in Newton/joules [N/J]).

For the current study, a single mass MSD model with a linear spring and a linear damper (9, 13, 16) was used and is described below:

The force produced by the spring is Fs = kspring*L

The force produced by the damper is Fd = kdamper*V

given that L is the length of the spring (leg deformation) and V is the velocity of the mass. The model was developed by one of the authors (B.O.) and coded in MatLab (Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts, United States) and applied to the VGRF. The constants kspring, kdamper as well as the drop height were optimized using the polytope search algorithm available in MatLab to fit the sum of Fs and Fd to the filtered ground reaction force data. Displacement of the center of mass is determined through the double integration of the vertical ground reaction force divided by the mass of the subject. The resulting spring and damping constants were considered independent variables in the study, while the type of landing was considered the dependent variable. Spring and damping constants in the ACLR group were then compared to those in the CTRL group. Inter-limb comparisons of the spring and damping constants were also made within the ACLR group.

Subjects

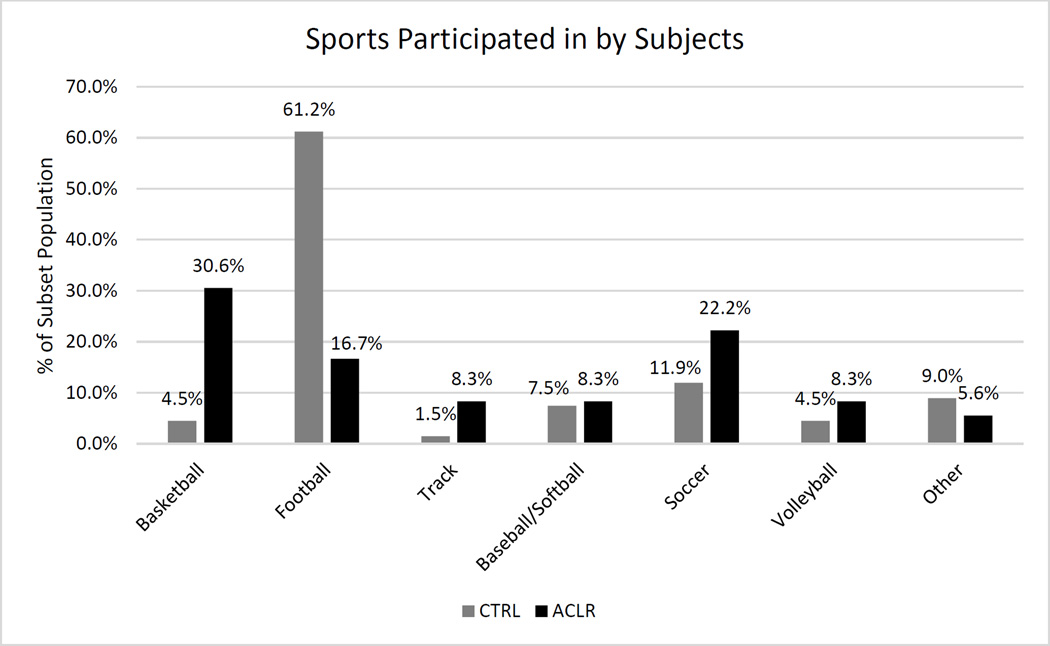

A total of 103 subjects involved with running/cutting sports were included in this study. The ACLR group was comprised of athletes who had undergone unilateral ACLR and returned to full participation in their primary sport within 1 year following surgery. Subjects in the ACLR group were asked to bring 1 to 2 matched teammates to be tested. These uninjured teammates served as the CTRL group (Table 1). Sixty-seven subjects (45 male, 22 female) served as the CTRL group and 36 subjects (10 male, 26 female) comprised the ACLR group. The sports played by subjects in each group at the time of testing are displayed in Figure 1. For the CTRL group, 78% indicated past participation in resistance training compared to 83% indicating resistance training experience in the ACLR group. The study was approved by the institutional review board at XXXXX and all participants (age 14.1 – 22.2 years) and guardians (if necessary) were informed of the benefits and risks of the investigation prior to signing an institutionally-approved informed consent document to participate in the study.. Participants completed a questionnaire to characterize their knee injury history. This history was confirmed via a personal interview with investigators. All testing occurred in a single day in early June.

Table 1.

Patient demographics. Independent t tests were utilized for comparing CTRL and ACLR groups. CTRL, control. ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

| Patient Demographics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL (n = 67) | ACLR (n = 36) | ||||

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | P = | |

| Age (yr) | |||||

| Total | 16.4 | ± 1.1 | 17.3 | ± 1.9 | 0.0096 |

| Male | 16.1 | ± 1.0 | 18.1 | ± 2.5 | 0.0380 |

| Female | 17 | ± 1.1 | 17 | ± 1.5 | 0.9768 |

| Height (cm) | |||||

| Total | 175.2 | ± 8.6 | 170.6 | ± 8.8 | 0.0137 |

| Male | 178.7 | ± 7.6 | 181 | ± 6.0 | 0.3363 |

| Female | 168 | ± 5.6 | 166.6 | ± 6.1 | 0.3947 |

| Body Mass (kg) | |||||

| Total | 76.5 | ± 23.9 | 73.6 | ± 17.8 | 0.4824 |

| Male | 83.8 | ± 25.6 | 93 | ± 17.8 | 0.2109 |

| Female | 61.7 | ± 8.2 | 66.1 | ± 10.7 | 0.1196 |

Figure 1.

Sports currently played by subjects, expressed as the percentage of each group, CTRL or ACLR, which participated in a particular sport.

Procedures

Data collection took place on one day in a setting designed to mimic National Football League (NFL) Combine testing procedures, but with certain modifications.(47) At each testing station, the same member of the research team instructed participants on how to properly perform the appropriate test and also demonstrated proper performance of the task. If a task was performed incorrectly or data could not be recorded, the participant immediately stopped and rested. As a result of participants’ previous experience in running/cutting sports with demands similar to those of the tested tasks, proper test performance frequently occurred after 1 practice trial by each participant. The order of limb testing was counterbalance randomized. Participants were given a minimum of 2 minutes rest and were encouraged to wait until they achieved full recovery after each testing station prior to testing the opposite limb or transferring to the next station. Prior to the testing session, analyses were performed on the testing force plates to assess reliability of single leg jumping and landing measures. During reliability testing the single leg vertical hop test showed good to excellent within-session reliability for peak power of both the right (ICC = 0.942) and left (ICC = 0.895) sides. Jump height showed excellent within session reliability for both the right (ICC = 0.963) and left (ICC = 0.940) sides. The between-session reliability for peak power between jumps was good for the right (ICC = 0.748) and left (ICC = 0.834) sides. Jump height showed good to excellent between-session reliability on the right (ICC = 0.794) and left (ICC = 0.909) sides.(28)

Anthropometric data (height, mass) were collected using a standard stadiometer (Weigh and Measure, LLC, Maryland, USA) and a digital scale (Tanita Health Equip. HK Ltd., Hong Kong). Limb dominance was determined by asking participants which leg they would use to kick a ball a maximum distance. Data from 2 jump tasks, described below, were analyzed for the current study. While nutrition and hydration were not controlled variables in the present study, ACLR group participants’ testing was matched for the time of day with CTRL group participants to limit the potential confounding effects of these variables.

Single Leg Drop Landing

Each subject was given a demonstration of a single leg drop landing from a box height of 0.31 m.(17) Subjects were instructed to drop off the box, to land on the ipsilateral foot directly in front of the box and to hold the landing for 3 seconds. Three randomized trials were performed for each limb. Two portable force platforms (AMTI, Accupower) were used to collect landing force. The portable force platforms used in this study were previously compared to a laboratory mounted force platform and demonstrated high validity and reliability.(62) Time history of VGRF was measured after the drop off of the box during the landing phase.

Single Leg Forward Broad Jump

Subjects were instructed to line up at their individual starting positions located at 50% of their maximum double-limb broad jump distance (taken from a previous test). Subjects were instructed to initiate the movement while balancing on one foot, to hop as far forward as possible, and to land on the ipsilateral foot with their heels beyond a tape line located at the front edge of a portable force plate. A landing stabilized for 1-second was required for a successful trial. Three randomized trials were performed for each limb. Maximum VGRF was recorded for each trial.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to characterize the study population and independent t tests were used to compare group demographic data. Landing force data was expressed using limb symmetry indices (LSI). In the ACLR group, the LSI was calculated as the value of the spring or damper constant in the involved leg divided by that of the uninvolved leg and as the dominant leg divided by that of the non-dominant leg in the CTRL group al multiplied by 100. Therefore, an LSI of 100% represents complete symmetry between the limbs. LSIs for each trial were used to calculate mean LSIs for each subject in each specific task. Asymmetry was calculated as difference between 1 and the LSI multiplied by 100 and was expressed as a percentage value with positive values indicating involved or non-dominant limb deficits and negative values indicating uninvolved or dominant limb deficits. As data was non-parametric, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was utilized for within group comparisons and the Mann-Whitney test was used for between group comparisons. Medians and interquartile ranges (the difference between 25th and 75th percentiles) were reported. Statistical significance was judged by an alpha level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Tables 2 and 3 present the mean spring and damping values for both groups during each task. Table 4 summarizes the results from the single-leg drop landing task. The ACLR group recorded significantly lower spring LSI (86.1%) than the CTRL group (98.2%; P = 0.015), meaning that the ACLR athletes had a greater tendency to land with decreased stiffness on their involved limb than the CTRL group athletes did on their dominant legs. The median spring asymmetry in the CTRL group was insignificant (1.8%; P = 0.46), while the ACLR group landed with increased stiffness in the uninvolved limb (13.9%; P = 0.021). The damping LSI was increased in the ACLR group (111.1%) relative to the CTRL group (103.6%; P = 0.045). The ACLR group had a median damping asymmetry of 11.1% in favor of the uninvolved limb (P = 0.004). The ACLR subjects landed with decreased stiffness (P = 0.006) and increased damping (P = 0.003) in their involved limbs compared to the non-dominant limbs of CTRL subjects.

Table 2.

Mean spring values ± SD for each limb in both groups. ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. CTRL, control.

| Single-Leg Drop Landing | ACLR (n=36) | CTRL (n=67) |

| Involved or Non-dominant | 79.25 ± 29.4 | 93.47 ± 26.53 |

| Uninvolved or Dominant | 92.29 ± 48.71 | 96.44 ± 28.80 |

| Single-Leg Broad Jump | ACLR (n=36) | CTRL (n=67) |

| Involved or Non-dominant | 166.74 ± 64.26 | 161.89 ± 65.42 |

| Uninvolved or Dominant | 160.71 ± 116.90 | 155.08 ± 74.44 |

Table 3.

Mean damping ratio values ± SD for each limb in both groups. ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. CTRL, control.

| Single-Leg Drop Landing | ACLR (n=36) | CTRL (n=67) |

| Involved or Non-dominant | 0.60 ± 0.11 | 0.54 ± 0.07 |

| Uninvolved or Dominant | 0.57 ± 0.18 | 0.52 ± 0.08 |

| Single-Leg Broad Jump | ACLR (n=36) | CTRL (n=67) |

| Involved or Non-dominant | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.07 |

| Uninvolved or Dominant | 0.52 ± 0.20 | 0.57 ± 1.07 |

Table 4.

Medians, interquartile ranges, and asymmetry of spring LSI and damping LSI for the CTRL and ACLR groups from the single-leg drop landing task. LSI, limb symmetry ratio. CTRL, control. ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

| Quartile | CTRL (n=67) (%) |

CTRL Asymmetry (%) |

ACLR (n=36) (%) |

ACLR Asymmetry (%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSI spring ratio |

25th percentile |

84.0 | 16.0 | 73.8 | 26.2 | N/A |

| 50th percentile |

98.2 | 1.8 | 86.1 | 13.9 | 0.015 | |

| 75th percentile |

113.3 | −13.3 | 95.3 | 4.7 | N/A | |

| LSI damping ratio |

25th percentile |

0.97.1 | 2.9 | 100.4 | −0.4 | N/A |

| 50th percentile |

103.6 | −3.6 | 111.1 | −11.1 | 0.045 | |

| 75th percentile |

109.3 | −9.3 | 117.3 | −17.3 | N/A |

Tables 2–4 about here The results from the single-leg forward broad jump are shown in Table 5. For this task, the ACLR group (111.7%) had a greater spring LSI than the CTRL group (90.3%; P = 0.045). The damping LSI was lower, but not to a significant degree, in the ACLR group (96.4%) than in the CTRL group (105.0%; P = 0.081). There were no significant interlimb differences in spring or damping values in either group.

Table 5.

Medians, interquartile ranges, and asymmetry of spring LSI and damping LSI for the CTRL and ACLR groups from the single leg forward broad jump task. LSI, limb symmetry ratio. CTRL, control. ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

| Quartile | CTRL (n=67) |

CTRL Asymmetry (%) |

ACLR (n=36) |

ACLR Asymmetry (%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSI spring ratio |

25th percentile |

74.1 | 25.9 | 8.01 | 19.9 | N/A |

| 50th percentile |

90.3 | 9.7 | 111.7 | −11.7 | 0.045 | |

| 75th percentile |

124.0 | −24.0 | 163.8 | −63.8 | N/A | |

| LSI damping ratio |

25th percentile |

92.0 | 8.0 | 76.1 | 23.9 | N/A |

| 50th percentile |

105.0 | −5.0 | 96.4 | 3.6 | 0.081 | |

| 75th percentile |

113.0 | −13.0 | 112.3 | −12.3 | N/A |

DISCUSSION

Biomechanical data has been utilized extensively to evaluate risk factors for ACL injury and deficits following ACL injury and surgical reconstruction.(11, 18, 23, 25, 44, 47, 48, 53, 54, 57, 64, 66) However, at the present time, these data have yet to adequately address the property of leg stiffness. As either too much and too little stiffness has been related to injury,(9) it is important for researchers to continue to investigate methods and models for the evaluation of leg stiffness. The purpose of this study was to use an MSD model to evaluate lower limb landing kinetics during two jumping tasks in uninjured athletes and athletes who had previously undergone ACLR. The data supported the a priori hypotheses that subjects who had undergone ACLR would display different lower limb kinetics than a healthy control group and that the ACLR subjects would display different kinetics on their involved limb relative to their uninvolved limb.

Both individual muscle stiffness and damping increase with increased muscle activation.(5, 10, 33, 39) These two properties are highly coupled by the (length-force, length-velocity) volume of the particular muscle which is activated.(50) On a larger scale, whole limb stiffness depends not only on muscle stiffness but also on the geometry of the leg itself, as limb stiffness increases with knee extension. The current findings indicate that ACLR athletes land with decreased involved limb stiffness (decreased spring constant values as calculated by the mass-spring damper model) relative to healthy counterparts during a single-leg drop landing task. Subjects who had undergone ACLR had a decreased spring LSI relative to the CTRL group, indicating that the ACLR cohort landed less stiffly on their involved leg than the CTRL group did on their dominant legs. Furthermore, the ACLR group exhibited a greater damping LSI than the CTRL group. This relationship persisted when directly comparing the ACLR involved limb to the CTRL non-dominant limb, as ACLR subjects landed on their involved limbs with decreased stiffness and increased damping. However, in the single-leg broad jump task, the ACLR athletes landed with a significantly greater spring LSI than the CTRL group. In addition, the ACLR group landed with a lower damping LSI than the CTRL group. Together, these results indicate that involved limb spring and damping characteristics in ACLR subjects may be task-specific.

The task-specific landing strategies may be influenced by the athletes’ height above the ground while jumping. The current data suggest that, as athletes land from a greater height above ground level, as in the single-leg drop landing task, leg stiffness in the ACL-involved limb decreases while damping increases. Kinematic data was not collected in the current study; however, increased knee flexion is the main method to decrease limb stiffness while muscle activation is constant. Overdamping, as seen in the ACLR group in the single-leg drop landing task, may serve to limit knee angle excursion (i.e. peak knee flexion) during landing. Decreased peak knee flexion angle has been reported as a predictor of ACL injury in female athletes.(25) Therefore, the decreased limb stiffness observed in the involved limbs of ACLR group participants relative to the non-dominant limbs of CTRL group participants may result in compensatory overdamping via quadriceps activation. The current cohort included an increased proportion of females, and this strategy is consistent with two previous reported neuromuscular imbalances commonly noted in female athletes at high risk for ACL injury.(26, 40, 43) Quadriceps dominance refers to the tendency towards greater quadriceps recruitment relative to hamstrings recruitment.(24, 43) For example, an ACLR athlete playing volleyball and landing after attempting a spike may initially contact the ground with greater knee flexion than a healthy peer. Based on the current data, a healthy athlete may be more likely to exhibit increased peak knee flexion while a similar athlete following ACLR may be more likely to use increased eccentric quadriceps activity that prevents him/her from achieving similar peak knee flexion angles. While quadriceps dominance is a risk factor for ACL injury,(24) it is unknown whether the strategy to initially decrease stiffness while landing is present prior to ACL injury or is a result of neuromuscular adaptations following ACLR. The current model may aid in the further investigation of this question thru the testing of healthy athletes followed by injury surveillance.

The neuromuscular imbalance known as leg dominance was also observed in the landing strategies of the ACLR cohort. Subjects who had undergone ACLR landed with lesser stiffness and damping on their involved limbs relative to their uninvolved limbs during the single-leg drop landing task. This asymmetry was not observed in this subset during the single-leg broad jump task. These data further support a theory of task-specific landing strategies in ACLR athletes and indicate that these athletes may display greater inter-limb differences in landing kinematics during athletic maneuvers as height above the ground increases. Side-to-side deficits in strength and coordination are commonly reported as predictors of injury risk, and may increase the risk for both limbs.(4, 25, 32, 43). Decreased stiffness has been previously implicated in etiology of musculoskeletal injury and these data indicate that ACL-involved knees may be at greater risk during landing maneuvers with greater vertical and lesser horizontal velocities.(2, 21) A spring-damper model may serve as a valuable adjunct to 3-D motion analysis data in that it may identify and track side-to-side asymmetries in stiffness so that they may be corrected via rehabilitation prior to sports participation.

Given the high reinjury rates in patients who return to sports involving pivoting and cutting after ACLR,(1, 55, 56, 58, 59, 63, 67) prevention strategies should have more priority during rehabilitation.(41, 42, 45, 46) Previous investigators implemented a jump-training program to examine the alterations of landing mechanics.(27) The program was focused on teaching subjects to land “softer”, thereby decreasing lower extremity stiffness. As a result of the jump-training program, subjects were able to decrease peak VGRF and reduce knee adduction and abduction moments while exhibiting similar knee flexion during landings. These data indicate that stiffness may be altered through training, and that the alteration can influence the loads experienced by the lower extremity, thereby potentially decreasing the risk of injury in healthy athletes. Recently, investigators demonstrated that simple instructions during a single-leg hop resulted in significant improvement of landing kinematics in patients after ACLR.(19). Those patients who received instructions with an external focus of attention (focus on the outcome) landed more softly, that is, with increased knee flexion. Patients who received internal focus instructions (attention directed to body movements) had compared to external focus, unfavorable lower knee flexion angles. Both of these examples are indications that specific biomechanical risk factors can be effectively modified in healthy athletes in order to reduce their risk of subsequent ACL injury. The current mass-spring-damper model may provide a more valid estimate of limb stiffness than VGRF and could be used alongside VGRF and other motion analysis data during screening and in injury prevention and rehabilitation programs to identify and correct landing asymmetries in at-risk and injured athletes.

Limitations

The model utilized in the current study is very simple and describes the overall stiffness and damping properties of the limbs during landing. The fitting of the model to previously collected data increases the ease with which comparisons can be made. However, a link to actual kinematic data would have allowed for further investigation of these comparisons and forms a limitation in the present paper. A greater proportion of the ACLR cohort were females compared to the control group. Differences in landing biomechanics have been reported between genders and may exist in the current study, but sex-specific analysis is beyond the scope of the current report, the aim of which was to compare lower limb kinetics of ACL-injured and healthy athletes with a mass-spring-damper model.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

The mass-spring-damper model employed in the current study identified differences in lower limb kinematics during two jumping tasks between healthy athletes and their peers who have undergone ACLR. These data indicated quadriceps dominance and leg dominance which likely played role a role in primary risk for ACL injury, persists in the landing strategies of athletes who undergo reconstruction and hope to return to sport following ACL injury. The proposed mass-spring-damper model may be a sensitive tool to support strength and conditioning practitioners in the identification of these previously reported imbalances. More importantly, the simplicity and limited equipment needed for this analysis indicate that the proposed mass-spring-damper model may support practitioners in the longitudinal monitoring of athletes’ responses to neuromuscular training protocols aimed at correcting biomechanical asymmetries in order to mitigate the risk of injury related to inadequate dynamic control.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of Funding:

The authors would like to acknowledge funding support from NFL Charities, National Institutes of Health/NIAMS grants R21 AR065068-01A1 and R01 AR056259-01

Footnotes

Laboratory:

Human Performance Laboratory, Division of Sports Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahldén M, Samuelsson K, Sernert N, Forssblad M, Karlsson J, Kartus J. The Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Register A Report on Baseline Variables and Outcomes of Surgery for Almost 18,000 Patients. The American journal of sports medicine. 2012;40:2230–2235. doi: 10.1177/0363546512457348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alentorn-Geli E, Myer GD, Silvers HJ, Samitier G, Romero D, Lazaro-Haro C, Cugat R. Prevention of non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer players. Part 1: Mechanisms of injury and underlying risk factors. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17:705–729. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andernord D, Desai N, Bjornsson H, Ylander M, Karlsson J, Samuelsson K. Patient Predictors of Early Revision Surgery After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Cohort Study of 16,930 Patients With 2-Year Follow-up. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;43:121–127. doi: 10.1177/0363546514552788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumhauer JF, Alosa DM, Renstrom AF, Trevino S, Beynnon B. A prospective study of ankle injury risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:564–570. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergmark A. Stability of the lumbar spine. A study in mechanical engineering. Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica Supplementum. 1989;230:1–54. doi: 10.3109/17453678909154177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourke HE, Gordon DJ, Salmon LJ, Waller A, Linklater J, Pinczewski LA. The outcome at 15 years of endoscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using hamstring tendon autograft for 'isolated' anterior cruciate ligament rupture. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 2012;94:630–637. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B5.28675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourke HE, Salmon LJ, Waller A, Patterson V, Pinczewski LA. Survival of the anterior cruciate ligament graft and the contralateral ACL at a minimum of 15 years. The American journal of sports medicine. 2012;40:1985–1992. doi: 10.1177/0363546512454414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brophy RH, Schmitz L, Wright RW, Dunn WR, Parker RD, Andrish JT, McCarty EC, Spindler KP. Return to play and future ACL injury risk after ACL reconstruction in soccer athletes from the Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) group. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2517–2522. doi: 10.1177/0363546512459476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler RJ, Crowell HP, 3rd, Davis IM. Lower extremity stiffness: implications for performance and injury. Clinical biomechanics. 2003;18:511–517. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(03)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crisco JJ, 3rd, Panjabi MM. The intersegmental and multisegmental muscles of the lumbar spine. A biomechanical model comparing lateral stabilizing potential. Spine. 1991;16:793–799. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199107000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Stasi S, Hartigan EH, Snyder-Mackler L. Sex-specific gait adaptations prior to and up to 6 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45:207–214. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2015.5062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Stasi S, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training to target deficits associated with second anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43:777–792. A771–A711. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutto DJ, Smith GA. Changes in spring-mass characteristics during treadmill running to exhaustion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1324–1331. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200208000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst GP, Saliba E, Diduch DR, Hurwitz SR, Ball DW. Lower extremity compensations following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Physical Therapy. 2000;80:251–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fältström A, Hägglund M, Magnusson H, Forssblad M, Kvist J. Predictors for additional anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: data from the Swedish national ACL register. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farley CT, Gonzalez O. Leg stiffness and stride frequency in human running. Journal of biomechanics. 1996;29:181–186. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Valgus knee motion during landing in high school female and male basketball players. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2003;35:1745–1750. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000089346.85744.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank BS, Gilsdorf CM, Goerger BM, Prentice WE, Padua DA. Neuromuscular fatigue alters postural control and sagittal plane hip biomechanics in active females with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sports Health. 2014;6:301–308. doi: 10.1177/1941738114530950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gokeler A, Benjaminse A, Welling W, Alferink M, Eppinga P, Otten B. The effects of attentional focus on jump performance and knee joint kinematics in patients after ACL reconstruction. Physical therapy in sport : official journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine. 2015;16:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gokeler A, Hof AL, Arnold MP, Dijkstra PU, Postema K, Otten E. Abnormal landing strategies after ACL reconstruction. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20:e12–e19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granata KP, Padua DA, Wilson SE. Gender differences in active musculoskeletal stiffness. Part II. Quantification of leg stiffness during functional hopping tasks. Journal of electromyography and kinesiology : official journal of the International Society of Electrophysiological Kinesiology. 2002;12:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(02)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hettrich CM, Dunn WR, Reinke EK, Group M, Spindler KP. The rate of subsequent surgery and predictors after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: two- and 6-year follow-up results from a multicenter cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1534–1540. doi: 10.1177/0363546513490277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hewett TE, Di Stasi SL, Myer GD. Current concepts for injury prevention in athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:216–224. doi: 10.1177/0363546512459638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR. Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Current women's health reports. 2001;1:218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Heidt RS, Jr, Colosimo AJ, McLean SG, van den Bogert AJ, Paterno MV, Succop P. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;33:492–501. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hewett TE, Paterno MV, Myer GD. Strategies for enhancing proprioception and neuromuscular control of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002:76–94. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hewett TE, Stroupe AL, Nance TA, Noyes FR. Plyometric training in female athletes. Decreased impact forces and increased hamstring torques. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:765–773. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hickey KC, Quatman CE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Brosky JA, Hewett TE. Methodological report: dynamic field tests used in an NFL combine setting to identify lower-extremity functional asymmetries. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:2500–2506. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b1f77b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaeding CC, Aros B, Pedroza A, Pifel E, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Dunn WR, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Wright RW, Spindler KP. Allograft Versus Autograft Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Predictors of Failure From a MOON Prospective Longitudinal Cohort. Sports health. 2011;3:73–81. doi: 10.1177/1941738110386185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaeding CC, Pedroza AD, Reinke EK, Huston LJ, Consortium M, Spindler KP. Risk Factors and Predictors of Subsequent ACL Injury in Either Knee After ACL Reconstruction: Prospective Analysis of 2488 Primary ACL Reconstructions From the MOON Cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1583–1590. doi: 10.1177/0363546515578836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamien PM, Hydrick JM, Replogle WH, Go LT, Barrett GR. Age, graft size, and Tegner activity level as predictors of failure in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring autograft. The American journal of sports medicine. 2013;41:1808–1812. doi: 10.1177/0363546513493896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knapik JJ, Bauman CL, Jones BH, Harris JM, Vaughan L. Preseason strength and flexibility imbalances associated with athletic injuries in female collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:76–81. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee H, Wang S, Hogan N. Relationship between Ankle Stiffness Structure and Muscle Activation. Ieee Eng Med Bio. 2012:4879–4882. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6347087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lind M, Menhert F, Pedersen AB. Incidence and outcome after revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction results from the Danish Registry for Knee Ligament Reconstructions. The American journal of sports medicine. 2012;40:1551–1557. doi: 10.1177/0363546512446000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Logerstedt D, Grindem H, Lynch A, Eitzen I, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Single-legged hop tests as predictors of self-reported knee function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2348–2356. doi: 10.1177/0363546512457551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magnussen RA, Lawrence JT, West RL, Toth AP, Taylor DC, Garrett WE. Graft size and patient age are predictors of early revision after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring autograft. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:526–531. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maletis GB, Inacio MC, Funahashi TT. Risk factors associated with revision and contralateral anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions in the Kaiser Permanente ACLR registry. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:641–647. doi: 10.1177/0363546514561745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marx RG, Jones EC, Angel M, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Beliefs and attitudes of members of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons regarding the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:762–770. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(03)00398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milner TE, Cloutier C. Damping of the wrist joint during voluntary movement. Experimental brain research. 1998;122:309–317. doi: 10.1007/s002210050519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myer GD, Brent JL, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Real-time assessment and neuromuscular training feedback techniques to prevent ACL injury in female athletes. Strength and conditioning journal. 2011;33:21–35. doi: 10.1519/SSC.0b013e318213afa8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myer GD, Ford KR, Brent JL, Hewett TE. An integrated approach to change the outcome part I: neuromuscular screening methods to identify high ACL injury risk athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26:2265–2271. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31825c2b8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myer GD, Ford KR, Brent JL, Hewett TE. An integrated approach to change the outcome part II: targeted neuromuscular training techniques to reduce identified ACL injury risk factors. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26:2272–2292. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31825c2c7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myer GD, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Rationale and Clinical Techniques for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention Among Female Athletes. J Athl Train. 2004;39:352–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myer GD, Martin L, Jr, Ford KR, Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Heidt RS, Jr, Colosimo A, Hewett TE. No association of time from surgery with functional deficits in athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: evidence for objective return-to-sport criteria. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2012;40:2256–2263. doi: 10.1177/0363546512454656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Myer GD, Paterno MV, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training techniques to target deficits before return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22:987–1014. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31816a86cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myer GD, Paterno MV, Ford KR, Quatman CE, Hewett TE. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: criteria-based progression through the return-to-sport phase. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:385–402. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myer GD, Schmitt LC, Brent JL, Ford KR, Barber Foss KD, Scherer BJ, Heidt RS, Jr, Divine JG, Hewett TE. Utilization of modified NFL combine testing to identify functional deficits in athletes following ACL reconstruction. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2011;41:377–387. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Myer GD, Wordeman SC, Sugimoto D, Bates NA, Roewer BD, Medina McKeon JM, DiCesare CA, Di Stasi SL, Barber Foss KD, Thomas SM, Hewett TE. Consistency of clinical biomechanical measures between three different institutions: implications for multi-center biomechanical and epidemiological research. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2014;9:289–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myklebust G, Bahr R. Return to play guidelines after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:127–131. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.010900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Needle AR, Baumeister J, Kaminski TW, Higginson JS, Farquhar WB, Swanik CB. Neuromechanical coupling in the regulation of muscle tone and joint stiffness. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24:737–748. doi: 10.1111/sms.12181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nikooyan AA, Veeger HE, Westerhoff P, Graichen F, Bergmann G, van der Helm FC. Validation of the Delft Shoulder and Elbow Model using in-vivo glenohumeral joint contact forces. Journal of biomechanics. 2010;43:3007–3014. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nikooyan AA, Zadpoor AA. Mass-spring-damper modelling of the human body to study running and hopping--an overview. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part H, Journal of engineering in medicine. 2011;225:1121–1135. doi: 10.1177/0954411911424210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palmieri-Smith RM, Lepley LK. Quadriceps Strength Asymmetry After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Alters Knee Joint Biomechanics and Functional Performance at Time of Return to Activity. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1662–1669. doi: 10.1177/0363546515578252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paterno MV, Ford KR, Myer GD, Heyl R, Hewett TE. Limb asymmetries in landing and jumping 2 years following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine. 2007;17:258–262. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31804c77ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of Contralateral and Ipsilateral Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injury After Primary ACL Reconstruction and Return to Sport. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22:116–121. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318246ef9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of Second ACL Injuries 2 Years After Primary ACL Reconstruction and Return to Sport. Am J Sports Med. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0363546514530088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Rauh MJ, Myer GD, Huang B, Hewett TE. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1968–1978. doi: 10.1177/0363546510376053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quatman CE, Quatman CC, Hewett TE. Prediction and prevention of musculoskeletal injury: a paradigm shift in methodology. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:1100–1107. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.065482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salmon L, Russell V, Musgrove T, Pinczewski L, Refshauge K. Incidence and risk factors for graft rupture and contralateral rupture after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:948–957. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.04.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shelbourne KD, Gray T, Haro M. Incidence of subsequent injury to either knee within 5 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:246–251. doi: 10.1177/0363546508325665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sward P, Kostogiannis I, Roos H. Risk factors for a contralateral anterior cruciate ligament injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:277–291. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-1026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walsh M, Ford K, Bangen K, Myer G, Hewitt T. Validation of a portable force plate to assessing jumping and landing performance; Presented at ISBS-Conference Proceedings Archive; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Webster KE, Feller JA, Leigh WB, Richmond AK. Younger patients are at increased risk for graft rupture and contralateral injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:641–647. doi: 10.1177/0363546513517540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Webster KE, Feller JA, Wittwer JE. Longitudinal changes in knee joint biomechanics during level walking following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Gait & posture. 2012;36:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Webster KE, Gonzalez-Adrio R, Feller JA. Dynamic joint loading following hamstring and patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Webster KE, Santamaria LJ, McClelland JA, Feller JA. Effect of fatigue on landing biomechanics after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:910–916. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31823fe28d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wiggins AJ, Grandhi RK, Schneider DK, Stanfield D, Webster KE, Myer GD. Risk of Secondary Injury in Younger Athletes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0363546515621554. 0363546515621554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]