Abstract

To establish a novel strategy for the control of fungal infection, we examined the antifungal and neutrophil-activating activities of antimicrobial peptides. The duration of survival of 50% of mice injected with a lethal dose of Candida albicans (5 × 108 cells) or Aspergillus fumigatus (1 × 108 cells) was prolonged 3 to 5 days by the injection of 10 μg of peptide 2 (a lactoferrin peptide) and 10 μg of α-defensin 1 for five consecutive days and was prolonged 5 to 13 days by the injection of 0.1 μg of granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and 0.5 μg of amphotericin B. When mice received a combined injection of peptide 2 (10 μg/day) with amphotericin B (0.5 μg/day) for 5 days after the lethal fungal inoculation, their survival was greatly prolonged and some mice continued to live for more than 5 weeks, although the effective doses of peptide 2 for 50 and 100% suppression of Candida or Aspergillus colony formation were about one-third and one-half those of amphotericin B, respectively. In vitro, peptide 2 as well as GM-CSF increased the Candida and Aspergillus killing activities of neutrophils, but peptides such as α-defensin 1, β-defensin 2, and histatin 5 did not upregulate the killing activity. GM-CSF together with peptide 2 but not other peptides enhanced the production of superoxide (O2−) by neutrophils. The upregulation by peptide 2 was confirmed by the activation of the O2−-generating pathway, i.e., activation of large-molecule guanine binding protein, phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase, protein kinase C, and p47phox as well as p67phox. In conclusion, different from natural antimicrobial peptides, peptide 2 has a potent neutrophil-activating effect which could be advantageous for its clinical use in combination with antifungal drugs.

Phagocytes play an essential role in the host defense against fungal invasion and growth. Functional phagocytes eliminate fungi from infected organs by releasing nitrogen oxide and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (2, 15, 29, 35). One approach to the control of fungal infections is therefore to enhance the generation of ROS in phagocytes. Several kinases are involved in the signal pathways in the generation of ROS, and the phosphorylating signal is eventually transduced to the electron-transporting complex, NADPH oxidase (12, 14, 39). It is therefore indicated that activation of the kinases involved in ROS generation is a useful means of controlling fungal infection (2). However, few agents have been developed for this purpose, and only granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is in clinical use (27).

During the last decade, biological studies have revealed much about the innate immune system. Along with the signals of bacterial toxins (polysaccharides and lipopolysaccharides) and viral DNA via Toll-like receptors, the biological characteristics of antimicrobial peptides continue to be clarified (19, 28). Each peptide exhibits a wide spectrum of activity against a variety of bacteria and fungi (25, 26). Defensins exhibit superior antimicrobial activities against gram-positive and -negative bacteria as well as fungi (10, 21, 43). α-Defensin 1 and β-defensin 2 are not constitutively expressed but are inducible. They are generated by and released from neutrophils and epithelial cells, respectively, in response to bacterial and fungal infections (13, 23, 32). These defensins therefore appear to play an important role in the protection of the host against microbial invasion. If both defensins have neutrophil-potentiating activities, especially ROS generation-stimulating activities, the defense coordinated with neutrophils and the peptides would be firm and functional. However, no investigation has indicated such neutrophil-activating activities of antimicrobial peptides.

Lactoferrin (Lf) was first found more than 30 years ago in human maternal milk, and its antimicrobial activity was ascertained soon thereafter (1, 34, 41, 42, 45). About 10 years later, the peptides lactoferricins B and H were synthesized, along with the bovine and human Lf amino acid sequences. These peptides possess higher anti-Candida activities than each original Lf (6, 7, 18). With reference to these peptides, our group synthesized a novel peptide (peptide 2) with stronger anticandidal activity than the full-length peptide, bovine Lf (38). Peptide 2 consists of the N-terminal 17 to 26 amino acids (FKCRRWQWRM) of bovine Lf. We already reported that the injection of peptide 2 and an antifungal drug, amphotericin B, combined prolonged the survival of mice into which Candida cells were injected (37). The in vivo effect of peptide 2 appeared to depend largely on neutrophil activation because the in vitro anticandidal activity of peptide 2 was less than 1/10 that of amphotericin B. Previous studies indicate that some antimicrobial peptides enhance neutrophil killing activity by stimulating the signal in the pathway to generate ROS (26). On the basis of this possibility, we examined the ex vivo and in vivo anticandidal and anti-Aspergillus activities of peptide 2, α-defensin 1, β-defensin 2, and histatin 5 and the influences of these peptides on neutrophils. The present study revealed that peptide 2 upregulates the generation of ROS in mouse neutrophils and protects mice against lethal Candida and Aspergillus infections in cooperation with amphotericin B.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell preparation and culture.

Candida albicans KSC1 was isolated from the oral cavity of a patient with oral candidiasis. The swabbed material was cultivated with Sabouraud dextrose agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C, and the growth was cultured in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium for about 20 h at 37°C. The growth in YPD medium was identified as C. albicans by using Candida check (Iatron Lab. Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and the organism was classified as serotype A according to the criteria of Fukazawa et al. (16). C. albicans strain TIMM0134 was used as a standard. Aspergillus fumigatus IF033022 was supplied by the Institute for Fermentation (Osaka, Japan). The organism was grown in potato dextrose agar at 24°C. The cells were then harvested and fixed by gently scraping the fungal mat into 1% Tween 80 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). All blastoconidial cells were filtered through sterile gauze, washed with PBS, counted with a hemacytometer, and stored at 4°C until they were needed. Cells in the exponential phase of growth were used in all experiments.

Peptides and antifungal drugs.

Peptide 2 was synthesized by Iwaki Glass Biolab Co. (Chiba, Japan) by a solid-phase method and was purified by high-performance liquid chromatography on a reverse-phase C18 column. The level of purity was >95%, as analyzed from the peak integration with high-performance liquid chromatograms at 214 nm. Both α-defensin 1 and β-defensin 2 were purchased from Peptide Institute Inc. (Osaka, Japan). Amphotericin B and histatin 5 were obtained from Sigma (Steinheim, Germany).

Determination of ED.

The effective dose (ED) of each agent against C. albicans or A. fumigatus was determined by a standard microdilution technique. Blastoconidial cells (103) were cultured in the presence or absence of each agent for 4 h. They were then transferred onto Sabouraud agar plates and cultured for 24 h at 37°C. The colonies that formed in each plastic dish were then counted. Five plates were used for each sample, and the mean colony counts were calculated from the colonies on the five plates. ED50 and ED100 indicate the concentrations of agent that limited growth to 50 and 0% of the number of CFU of the control (which received no treatment), respectively.

Treatment of mice.

Specific-pathogen-free inbred CBA/N female mice (age, 8 weeks) were used in the present study. A total of 5 × 108 spores of C. albicans were administered intraperitoneally, and 1 × 108 spores of A. fumigatus were administered into the lungs of other groups of mice through an intratracheal tube. From the day of challenge, saline, peptide 2 (10 or 20 μg/mouse), α-defensin 1 (10 or 20 μg/mouse), GM-CSF (0.1 or 0.5 μg/mouse), amphotericin B (0.1 or 0.5 μg/mouse), or a combination of these agents was administered intravenously once a day for five consecutive days. The mice were fed solid feed (Clea Japan, Inc.). Ten mice were used in each treatment group.

Neutrophil preparation.

Neutrophils were separated from heparinized peripheral blood from healthy individuals. After centrifugation at 400 × g for 10 min, the buffy coat layer was collected, diluted in 3 volumes of PBS, and centrifuged on Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Piscataway, N.J.) gradients by Boyüm's method. The pellets were resuspended in PBS containing 3% (wt/vol) dextran to remove any contaminating erythrocytes. After centrifugation, the neutrophils were resuspended in a hypotonic buffer solution, and the residual erythrocytes were removed. A purity of >95% and cell viability of >98% were confirmed by Giemsa staining and trypan blue exclusion, respectively.

O2− generation assay.

The generation of superoxide (O2−) was assayed by the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction method. Neutrophils (106 cells/well) were incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 1 h at 37°C in Hanks buffered saline solution containing 1 mg of NBT per ml, with or without 10−9 M phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), 10−7 M N-formylmethionyl leucyl phenylalanine (FMLP), or 2.5 mg of opsonized zymosan (OZ) per ml. The optical density at 550 nm in each well was examined with a plate reader.

Killing activities of neutrophils.

C. albicans or A. fumigatus blastoconidia were labeled with Na251CrO4 at a concentration of 100 μCi per 108 cells for 1 h at 37°C. The blastoconidia were then washed twice and used as targets. The effector cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and were then mixed with the 51Cr-labeled blastoconidia to give an effector cell/target cell ratio of 1:10 in a final volume of 0.2 ml/flat-bottom well. The mixtures were incubated for 4 h at 37°C, and the isotope activity in 0.1 ml of the supernatant from each well was measured with a gamma scintillation counter. The percent cytotoxicity was calculated by the following formula: [(experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximal release − spontaneous release)] × 100, where spontaneous release is the isotope activity in the target cells incubated without effector cells, maximal release is the isotope activity in the supernatant after treatment of the blastoconidia with 0.1% Triton X-100, and the units for all release values are counts per minute. Values were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate assays.

Western blotting.

Proteins were extracted from the separated neutrophils by lysing them with TNE lysis buffer (1 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 0.5 M EDTA, 10% Nonidet P-40), and the total protein level in each sample was determined by the method of Lowry et al. (24). The protein level in each lysate was adjusted to 40 μg/30 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, and the lysate samples were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting, which was performed with anti-p47phox, anti-p67phox, anti-PI3-K, and anti-PKC antibodies (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, Ky.) and anti-Ras GAP antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.).

PKC activity.

Protein kinase C (PKC) activity was measured with a MESACUP protein kinase assay kit (MBL, Nagoya, Japan), based on the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Briefly, after the fractionation of neutrophils by the method of Balazovich and Boxer (4), the cytosol fraction was reacted with phosphatidylserine peptide-coated microplates in the presence of 1 mM ATP. After 20 min of incubation at 25°C, biotinylated monoclonal antibody 2B9, which bound to the phosphorylated form of the phosphatidylserine peptide, was added, and the mixture was incubated at 25°C for 60 min. After the mixture was washed, peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin was added and the mixture was incubated for 60 min; peroxidase substrate was then added. The PKC activity was determined from the intensity of the color measured photometrically at 492 nm.

G-protein activation.

Guanine binding protein (G-protein) activation was determined by measuring the stimulation of [γ-35S]GTP binding. After pretreatment with or without 50 ng of pertussis toxin per ml and 100 ng of cholera toxin per ml for 1 h, the neutrophils were washed twice with buffer A, which contained 20 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.4). The cells were harvested and homogenized with a kinematica Polytron homogenizer in buffer A. The suspension was centrifuged twice at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The pellet, which included the membrane fraction, was then preincubated for 15 min with peptide 2 in buffer B, which contained 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.1 μM GDP, 50 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl; and the reaction was started with 0.2 nM [γ-35S]GTP in a final volume of 200 μl in 96-well plates at room temperature for 60 min. The experiments were terminated by rapid filtration of the mixture through Unifilter-96 GF/B filters by use of a Filtermate harvester. The amount of radioactivity that was retained on the filters was determined with a Top Count microplate scintillation counter. The examination was performed in triplicate, and the values presented in the figures are expressed as the means ± standard deviations of triplicate assays.

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were performed in duplicate, and each value is shown as the mean ± standard deviation. The significance of differences between sets of data was determined by Student's t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Antifungal activities of peptides in vitro.

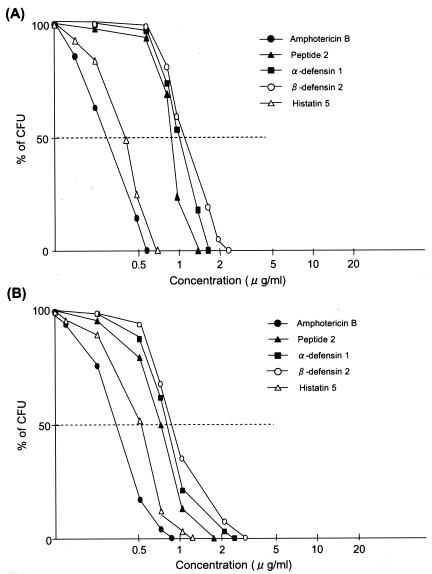

Compared with the activity of amphotericin B, all peptides examined had very weak antifungal activities (Fig. 1). The ED100 of amphotericin B was 0.62 μg/ml against C. albicans strain KSC1, obtained from a patient, and those of peptide 2, α-defensin 1, β-defensin 2, and histatin 5 were 1.22, 1.50, 2.50, and 0.77 μg/ml, respectively. The standard strain, TIMM0134, was a little more sensitive to these agents than KSC1, with the ED100s of amphotericin B, peptide 2, α-defensin 1, β-defensin 2, and histatin 5 against TIMM0134 being 0.50, 1.15, 1.25, 2.25, and 0.70 μg/ml, respectively. Amphotericin B and these peptides exhibited similar patterns of inhibition of A. fumigatus and C. albicans growth, although the ED of each agent was a little higher against A. fumigatus than against C. albicans; the ED100s of amphotericin B, α-defensin 1, and peptide 2 were 0.85, 2.25, and 1.65 μg/ml, respectively.

FIG. 1.

In vitro antifungal activities of antimicrobial peptides. C. albicans (A) and A. fumigatus (B) (103 cells/ml) were cultured in Dulbecco minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum in the presence or absence of amphotericin B (0.125 to 1 μg/ml), peptide 2 (0.25 to 2 μg/ml), α-defensin 1 (0.25 to 5 μg/ml), β-defensin 2 (0.25 to 5 μg/ml), or histatin 5 (0.125 to 2 μg/ml) for 4 h at 37°C. After two washes with PBS, the cells were cultured on Sabouraud dextran agar for 24 h at 37°C, and the colonies that formed were counted.

Survival-prolonging effects of peptides for mice infected with C. albicans or A. fumigatus.

When 5 × 108 cells of C. albicans were inoculated intraperitoneally, all the mice died within 8 days, with a 50% survival duration (the duration from the time of Candida inoculation to the times of death of five mice) of 6 days (Table 1). Serial injection of 10 and 20 μg of peptide 2/day for 5 days prolonged the 50% survival rates to 10 and 14 days, respectively. The anticandidal effect of α-defensin 1 was a little less than that of peptide 2. Compared with the activities of these two peptides, amphotericin B at 0.5 μg/day revealed a further strong anticandidal effect, with a 50% survival rate of 19 days, although all the infected mice had died by 25 days after the injection. The mice that underwent treatment with both peptide 2 and amphotericin B or with both α-defensin 1 and amphotericin B survived for a long time, and four of the mice treated with 20 μg of peptide 2 and 0.5 μM amphotericin B survived throughout the observation period. The mean length of survival of mice treated with the combination of peptide 2 (20 μg/ml) and amphotericin B (0.5 μg/ml) was longer than that of mice treated with amphotericin B alone (P < 0.05, Student's t test) (Table 1). The combination of α-defensin 1 and GM-CSF with peptide 2 had a weak anticandidal effect compared with the effects of the other combinations. The prolongation of survival as a result of treatment with each peptide and combination of peptides with amphotericin B for A. fumigatus-injected mice was similar to that for C. albicans-injected mice. The effect of the combination of peptide 2 and amphotericin B was most prominent in both C. albicans- and A. fumigatus-inoculated mice.

TABLE 1.

In vivo antifungal effects of antimicrobial peptidesa

| Time (days) to death of 50% of mice

|

Mean survival time (days)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | Peptide 2 (μg)

|

α-Defensin 1 (μg)

|

GM-CSF (μg)

|

Amphotericin B (μg)

|

Peptide 2 (10) + amphotericin B (0.5) | Peptide 2 (20) + amphotericin B (0.5) | Peptide 2 (10) + α-defensin 1 (10) + amphotericin B (0.5) | Peptide 2 (10) + α-defensin 1 (10) + GM-CSF (0.1) | Saline | Peptide 2 (μg)

|

α-Defensin 1 (μg)

|

GM-CSF (μg)

|

Amphotericin B (μg)

|

Peptide 2 (10) + amphotericin B (0.5) | Peptide 2 (20) + amphotericin B (0.5) | Peptide 2 (10) + α-defensin 1 (10) + amphotericin B (0.5) | Peptide 2 (10) + α-defensin 1 (10) + GM-CSF (0.1) | |||||||||

| 10 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | |||||||||||

| C. albicans | 6 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 19 | 24 | >28 | >29 | 23 | 5.4 ± 1.8 | 7.8 ± 2.8 | 11.1 ± 3.0 | 7.3 ± 3.3 | 9.4 ± 4.0 | 12.2 ± 4.2 | 13.7 ± 4.5 | 14.4 ± 4.4 | 17.9 ± 5.6b | >24.9 ± 6.8b | >28.1 ± 6.3bc | >30.3 ± 6.8bc | >20.8 ± 6.3b |

| A. fumigatus | 7 | 12 | 14 | 10 | 14 | 12 | 16 | 13 | 17 | 26 | >30 | >30 | 23 | 6.8 ± 2.6 | 9.8 ± 3.5 | 13 ± 3.5 | 8.9 ± 3.7 | 11.8 ± 4.5 | 12.9 ± 3.2 | 14.3 ± 4.7 | 14.6 ± 5.8 | 17.6 ± 4.7b | >24.3 ± 7.1b | >28.5 ± 6.0bc | >31.2 ± 7.1bc | >20.4 ± 6.8b |

Each mouse received an intraperitoneal inoculation of 5 × 108 cells of A. fumigatus. From the first day to the fifth day, saline, peptide 2 (10 or 20 μg), α-defensin 1 (10 or 20 μg), GM-CSF (0.1 or 0.5 μg), amphotericin B (0.1 or 0.5 μg), or peptide 2 (10 μg)-α-defensin 1 (10 μg)-amphotericin B (0.5 μg) was administered through the caudal vein each day. Ten mice were used in each treatment group. For combinations, values in parentheses are in micrograms.

P < 0.05 versus results for group treated with saline.

P < 0.05 versus results for group treated with amphotericin B alone.

Influences of antimicrobial peptides on Candida and A. fumigatus killing activities of neutrophils and O2− generation.

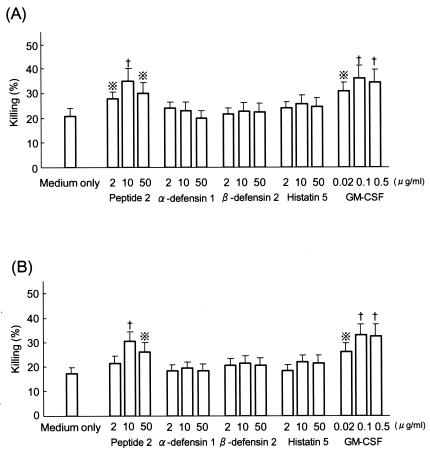

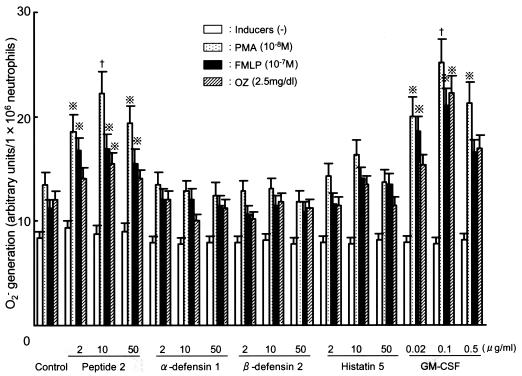

Although α-defensin 1, β-defensin 2, and histatin 5 did not upregulate the killing activities of neutrophils against C. albicans and A. fumigatus, peptide 2 did (Fig. 2). The killing activity upregulated by peptide 2 (10 μg/ml)-treated neutrophils was similar to that upregulated by GM-CSF (0.1 μg/ml)-treated neutrophils. Neutrophils pretreated with peptide 2 or GM-CSF and then treated with an O2− inducer, PMA, FMLP, or OZ, generated higher levels of O2− than control neutrophils (Fig. 3). O2− generation was most strongly induced by PMA in peptide 2-pretreated neutrophils. The level of upregulation of O2− generated by peptide 2 (10 μg/ml) pretreatment was almost the same as that generated by GM-CSF (0.1 μg/ml) pretreatment.

FIG. 2.

Influence of antimicrobial peptides on Candida and Aspergillus killing activities of neutrophils. Neutrophils separated from human peripheral blood were treated with each agent for 30 min at 37°C and then cocultured with 51Cr-labeled C. albicans (A) or A. fumigatus (B) at an effector cell/target cell ratio of 1 to 10 for 4 h at 37°C. The amount of isotope in the culture supernatant was then measured with a gamma scintillation counter. Cross with dots symbol, P < 0.05 by Student's t test; †, P < 0.02 by Student's t test.

FIG. 3.

Priming effects of antimicrobial peptides on O2− generation by neutrophils. Neutrophils obtained from human peripheral venous blood were treated with each agent for 30 min at 37°C. Then, 106 cells were poured into each microplate well and the O2− inducer was added. One hour after the addition of the inducers, the amount of O2− generated in the supernatants was measured by an NBT reduction method. Cross with dots symbol, P < 0.05 by Student's t test; †, P < 0.02 by Student's t test.

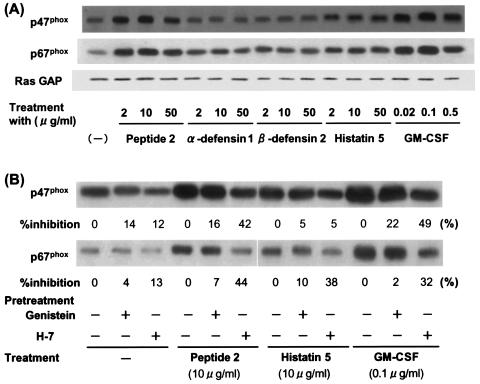

Influences of peptides on NADPH oxidase and O2− signal pathway.

The expression of NADPH oxidase components, p47phox and p67phox, was increased by peptide 2 as well as by GM-CSF, but the other peptides tested only weakly upregulated the expression of these components (Fig. 4). When neutrophils were pretreated with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, genistein, or a PKC inhibitor, H-7, the expression of p47phox and p67phox upregulated by peptide 2 and GM-CSF was strongly suppressed, especially by H-7 pretreatment. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) expression was increased by treatment of the neutrophils with peptide 2 or GM-CSF (Fig. 5A). Histatin 5 also upregulated PI3-K expression, but the increase was very low (Fig. 5B). In parallel with PI3-K activation, PKC activity was strongly increased by GM-CSF and peptide 2 treatment and was weakly increased by treatment with histatin 5 and other peptides.

FIG. 4.

Influence of antimicrobial peptides on p47phox and p67phox. Neutrophils obtained and separated from human peripheral blood were treated with each agent for 30 min without pretreatment (A) or after a 30-min pretreatment with genistein (20 μM) or H-7 (50 μM) (B). Cellular proteins were then extracted and blotted with antibodies against p47phox and p67phox.

FIG. 5.

Influence of antimicrobial peptides on PI3-K (A) and PKC (B) activities. (A) Neutrophils separated from human peripheral venous blood were treated with each agent for 5 or 10 min at 37°C, and extracted cellular proteins were blotted with antibody against PI3-K. (B) Neutrophils separated from human peripheral venous blood were treated with peptide 2 (2, 10, and 50 μg/ml), GM-CSF (0.02, 0.1 and 0.5 μg/ml), α-defensin 1 (2, 10, and 50 μg/ml), β-defensin 2 (2, 10, and 50 μg/ml) and histatin 5 (2, 10, and 50 μg/ml) for the indicated periods. Cont, control.

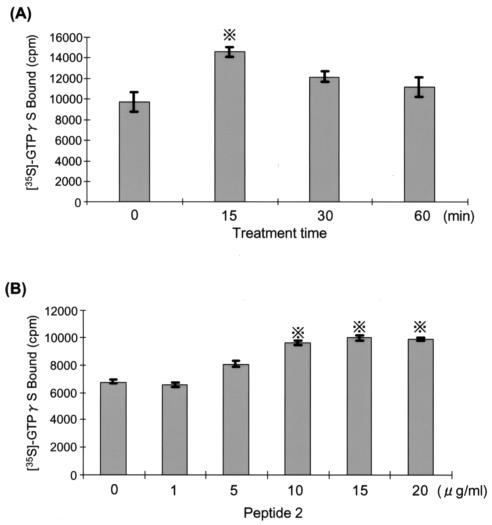

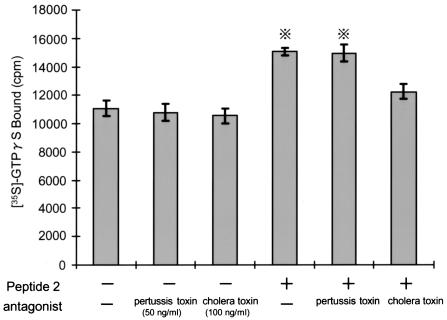

Peptide 2 activated G protein in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6). The activation reached a peak after 15 min of treatment with 10 μg of peptide 2/ml. The membrane fraction was obtained from neutrophils pretreated with a G-protein antagonist, pertussis toxin or cholera toxin, and the amount of [γ-35S]GTP bound was estimated (Fig. 7). G-protein activation by peptide 2 was not influenced by pertussis toxin but was suppressed by cholera toxin.

FIG. 6.

Influence of peptide 2 on large G protein. Neutrophils separated from human peripheral venous blood were fractionated into the cytosol and membrane, and the membrane fraction was treated with peptide 2 (10 μg/ml) for the indicated times (A) or with the indicated doses of peptide 2 for 15 min (B). The membrane fraction was then reacted with [γ-35S]GTP for 60 min at 37°C and the amount of membrane-bound [γ-35S]GTP was measured with a gamma scintillation counter. Cross with dots symbol, P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

FIG. 7.

Influences of pertussis and cholera toxins on peptide 2-activated large G protein. Neutrophils separated from human peripheral venous blood were pretreated with pertussis toxin (50 ng/ml) or cholera toxin (100 ng/ml) for 60 min at 37°C. After a wash, the membrane fraction was separated, treated with peptide 2 (10 μg/ml) for 15 min, and allowed to react with [γ-35S]GTP for 60 min. The amount of membrane-bound [γ-35S]GTP was measured with a gamma scintillation counter. Cross with dots symbol, P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

DISCUSSION

Fungal infections are serious problems during the treatment of immunosuppressive viral infections, malignant tumors, and other immunocompromising disorders (17, 30, 31). Novel drugs with potent antifungal activities have been developed (9, 11), but they have insufficiently controlled fungal infections in immunocompromised patients, and a new strategy for control is desired. Recently, antimicrobial peptides have been found, and their biological activities have been studied with the hope that they may be used clinically (10, 22, 25, 26, 33, 36, 40). It was reported, for example, that histatin 5, which is generated from epithelial cells such as salivary gland cells and secreted into saliva, exhibited antifungal activity by binding to the fungal cell membrane and inducing ATP efflux (3, 8, 13, 20, 44). Other investigators have reported that defensins as well as histatins induce histamine release from mast cells (5). These reports suggest that antimicrobial peptides generally possess both fungal growth-inhibitory activities and leukocyte-activating activities. If they do possess both types of activities, combined therapy with antimicrobial peptides and synthesized antifungal drugs can be expected to control fungal infections.

Compared with the antifungal drug amphotericin B, all peptides examined exhibited weaker activities on the inhibition of colony formation. Of the peptides tested, histatin 5 possessed the strongest activity against C. albicans and A. fumigatus, but its effect was slight lower than that of amphotericin B. The low levels of antifungal activity of the peptides appear to indicate that peptides alone, even at high doses, cannot remove fungi from an infected site if they do not activate phagocytes or if they do not cooperate synergistically with antifungal drugs. In vitro, the C. albicans- and A. fumigatus-killing activities of neutrophils were increased by peptide 2 to levels near those of GM-CSF-treated neutrophils. However, the remaining three peptides, α-defensin 1, β-defensin 2, and histatin 5, did not upregulate the killing activities of neutrophils. Consistent with this result, peptide 2 and GM-CSF primed neutrophils to generate O2−, although combinations of GM-CSF with other peptides did not. The priming effect of peptide 2 was most strongly observed in PMA-treated neutrophils and was almost completely suppressed by a PKC inhibitor, H-7, while the upregulation of O2− production by GM-CSF was nearly the same among PMA-, FMLP-, and OZ-treated neutrophils. This result suggests that peptide 2 activates some molecules on the PKC pathway to O2− generation. Dose-dependent increases in the killing activity and O2− generation were not observed in the upregulation of neutrophil function by peptide 2; that is, the upregulated activities of the neutrophils were instead decreased by treatment of neutrophils with a high dose (50 μg/ml) of peptide 2. The accurate mechanism is unclear, but the decrease in neutrophil function obtained with 50 μg of peptide 2/ml was consistent with the decreased levels of expression of p47phox and p67phox in neutrophils treated with the same dose of peptide 2. A suppressive signal appears to be induced by the high dose of peptide 2, which was similarly observed with 0.5 μg of GM-CSF/ml.

Although treatment with 20 μg of peptide 2 and α-defensin 1 per mouse revealed the survival prolongation effects in mice, their effects were weaker than that of amphotericin B. The combination of peptide 2 and amphotericin B, however, largely prolonged the survival times of the mice. The effect of the combination was, however, weakly synergistic. The weak synergistic effect appears to be derived from the neutrophil-activating activity of peptide 2.

The generation of O2− is under the control of the NADPH oxidase-activating signal (39, 46). For the activation of NADPH oxidase, its cytosol components, p47phox, p67phox and GTP-bound Rac, must move to the membrane and form a complex with p22phox and gp91phox (2). Interestingly, the present study revealed that peptide 2 as well as GM-CSF upregulated p47phox and p67phox expression, but the other peptides tested did not. The upregulated expression was almost completely suppressed by H-7 and was only weakly suppressed by a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, genistein. The suppression by H-7 suggested that the activation of PKC was induced by peptide 2 and GM-CSF. As expected, an increase in PKC activity was observed by the treatment of human peripheral blood neutrophils with peptide 2 and GM-CSF. The activation of PKC was supported by the finding that peptide 2 and GM-CSF increased the level of expression of PI3-K, which is the upstream kinase of PKC. Compared with the increase in PKC activity achieved with these two agents, α-defensin 1, β-defensin 2, and histatin 5 increased PKC activity only slightly.

Cell surface receptors and cell membrane-associated kinases play a critical role in the signal pathways associated with cell activation. Large G proteins are involved in the signal pathways in the generation of ROS, and some O2− inducers, for example, FMLP, bind to large G proteins; the signal required to generate O2− is transduced downward via PI3-K and PKC to NADPH oxidase (2, 14, 39). The present study demonstrated that peptide 2 activated G protein and that the activation was largely suppressed by cholera toxin but not by pertussis toxin, and cholera toxin suppressed p47phox and p67phox activation by peptide 2. From these results, peptide 2 appears to activate the cytosol components of NADPH oxidase through the G protein-PI3-K-PKC pathway and does not appear to use a pathway that involves mitogen-activated kinase. In addition, peptide 2 likely binds to certain receptors on the cell surface which are coupled with G protein, perhaps the Gs subunit. However, the result that cholera toxin did not completely suppress G-protein activation by peptide 2 suggests the existence of other pathways in the signaling of peptide 2.

The upregulation of O2− generation and the fungicidal activities of peptide 2-treated neutrophils indicate a potent antifungal effect in vivo. In fact, the injection of peptide 2 and amphotericin B combined brought about a far greater prolongation of the survival time in mice inoculated with a lethal dose of C. albicans or A. fumigatus. A combination of peptide 2 and gentamicin also had a potent anticandidal effect in vivo (data not shown). The synergistic effect of peptide 2 in the combination largely appears to depend on the neutrophil-activating activity of peptide 2. However, another mechanism likely appears to be involved in the synergistic cooperation between peptide 2 and amphotericin B. Furthermore, compared with histatin 5, peptide 2 increased the rate of ATP efflux from both C. albicans and A. fumigatus cells and decreased the intracellular ATP level, although GM-CSF did not affect the ATP level (unpublished data), suggesting that the levels of intracellular antifungal drugs were increased by peptide 2 because of the decreased levels of efflux of antifungal drugs. These effects of peptide 2 on neutrophils and fungal cells therefore appear to indicate a new strategy for the control of fungal infections. For the application of peptide 2 as part of combination therapy, a pharmacological investigation of peptide 2, including the possibility of antibody formation, is required.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilera, O., M. T. Andres, J. Heath, J. F. Fierro, and C. W. Douglas. 1998. Evaluation of the antimicrobial effect of lactoferrin on Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, and Prevotella nigrescens. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 21:29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aratani, Y., F. Kura, H. Watanabe, H. Akagawa, Y. Takano, K. Suzuki, M. C. Dinauer, N. Maeda, and H. Koyama. 2002. Relative contributions of myeloperoxidase and NADPH-oxidase to the early host defense against pulmonary infections with Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Med. Mycol. 40:557-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baev, D., X. S. Li, J. Dong, P. Keng, and M. Edgerton. 2002. Human salivary histatin 5 causes disordered volume regulation and cell cycle arrest in Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 70:4777-4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balazovich, K. J., and L. A. Boxer. 1990. Extracellular adenosine nucleotides stimulate protein kinase C activity and human neutrophil activation. J. Immunol. 144:631-637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Befus, A. D., C. Mowat, M. Gilchrist, J. Hu, S. Solomon, and A. Bateman. 1999. Neutrophil defensins induce histamine secretion from mast cells: mechanisms of action. J. Immunol. 163:947-953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellamy, W., M. Takase, H. Wakabayashi, K. Kawase, and M. Tomita. 1992. Antibacterial spectrum of lactoferricin B, a potent bactericidal peptide derived from the N-terminal region of bovine lactoferrin. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 73:472-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellamy, W., M. Takase, K. Yamauchi, H. Wakabayashi, K. Kawase, and M. Tomita. 1992. Identification of the bactericidal domain of lactoferrin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1121:130-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bercier, J. G., I. Al-Hashimi, N. Haghighat, T. D. Rees, and F. G. Oppenheim. 1999. Salivary histatins in patients with recurrent oral candidiasis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 28:26-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowman, J. C., P. S. Hicks, M. B. Kurtz, H. Rosen, D. M. Schmatz, P. A. Liberator, and C. M. Douglas. 2002. The antifungal echinocandin caspofungin acetate kills growing cells of Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3001-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cullor, J. S., M. J. Mannis, C. J. Murphy, W. L. Smith, M. E. Selsted, and T. W. Reid. 1990. In vitro antimicrobial activity of defensins against ocular pathogens. Arch. Ophthalmol. 108:861-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denning, D. W. 2003. Echinocandin antifungal drugs. Lancet 362:1142-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dreiem, A., O. Myhre, and F. Fonnum. 2003. Involvement of the extracellular signal regulated kinase pathway in hydrocarbon-induced reactive oxygen species formation in human neutrophil granulocytes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 190:102-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edgerton, M., S. E. Koshlukova, M. W. Araujo, R. C. Patel, J. Dong, and J. A. Bruenn. 2000. Salivary histatin 5 and human neutrophil defensin 1 kill Candida albicans via shared pathways. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3310-3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Bekay, R., M. Alvarez, M. Carballo, J. Martin-Nieto, J. Monteseirin, E. Pintado, F. J. Bedoya, and F. Sobrino. 2002. Activation of phagocytic cell NADPH oxidase by norfloxacin: a potential mechanism to explain its bactericidal action. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71:255-261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fierro, I. M., C. Barja-Fidalgo, F. Q. Cunha, and S. H. Ferreira. 1996. The involvement of nitric oxide in the anti-Candida albicans activity of rat neutrophils. Immunology 89:295-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukazawa, Y., T. Shinoda, and T. Tsuchiya. 1968. Response and specificity of antibodies for Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 95:754-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottfredsson, M., J. J. Vredenburgh, J. Xu, W. A. Schell, and J. R. Perfect. 2003. Candidemia in women with breast carcinoma treated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation. Cancer 98:24-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groenink, J., E. Walgreen-Weterings, W. van't Hof, E. C. Veerman, and A. V. Nieuw Amerongen. 1999. Cationic amphipathic peptides, derived from bovine and human lactoferrins, with antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:217-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi, F., T. K. Means, and A. D. Luster. 2003. Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood 102:2660-2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helmerhorst, E. J., P. Breeuwer, W. van't Hof, E. Walgreen-Weterings, L. C. Oomen, E. C. Veerman, A. V. Amerongen, and T. Abee. 1999. The cellular target of histatin 5 on Candida albicans is the energized mitochondrion. J. Biol. Chem. 274:7286-7291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagan, B. L., T. Ganz, and R. I. Lehrer. 1994. Defensins: a family of antimicrobial and cytotoxic peptides. Toxicology 87:131-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, D. G., Y. Park, H. N. Kim, H. K. Kim, P. I. Kim, B. H. Choi, and K. S. Hahm. 2002. Antifungal mechanism of an antimicrobial peptide, HP (2-20), derived from N-terminus of Helicobacter pylori ribosomal protein L1 against Candida albicans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 291:1006-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehrer, R. I., T. Ganz, D. Szklarek, and M. E. Selsted. 1988. Modulation of the in vitro candidacidal activity of human neutrophil defensins by target cell metabolism and divalent cations. J. Clin. Investig. 81:1829-1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosenbrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lupetti, A., R. Danesi, J. W. van't Wout, J. T. van Dissel, S. Senesi, and P. H. Nibbering. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides: therapeutic potential for the treatment of Candida infections. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 11:309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller, F. M., C. A. Lyman, and T. J. Walsh. 1999. Antimicrobial peptides as potential new antifungals. Mycoses 42:77-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Natarajan, U., N. Randhawa, E. Brummer, and D. A. Stevens. 1998. Effect of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor on candidacidal activity of neutrophils, monocytes or monocyte-derived macrophages and synergy with fluconazole. J. Med. Microbiol. 47:359-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Netea, M. G., C. A. Van Der Graaf, A. G. Vonk, I. Verschueren, J. W. Van Der Meer, and B. J. Kullberg. 2002. The role of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 in the host defense against disseminated candidiasis. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1483-1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Netea, M. G., J. W. Meer, I. Verschueren, and B. J. Kullberg. 2002. CD40/CD40 ligand interactions in the host defense against disseminated Candida albicans infection: the role of macrophage-derived nitric oxide. Eur. J. Immunol. 32:1455-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reichart, P. A. 2003. Oral manifestations in HIV infection: fungal and bacterial infections, Kaposi's sarcoma. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berlin) 192:165-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiss, E., K. Tanaka, G. Bruker, V. Chazalet, D. Coleman, J. P. Debeaupuis, R. Hanazawa, J. P. Latge, J. Lortholary, K. Makimura, C. J. Morrison, S. Y. Murayama, S. Naoe, S. Paris, J. Sarfati, K. Shibuya, D. Sullivan, K. Uchida, and H. Yamaguchi. 1998. Molecular diagnosis and epidemiology of fungal infections. Med. Mycol. 36:249-257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schroder, J. M., and J. Harder. 1999. Human beta-defensin-2. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 31:645-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Situ, H., G. Wei, C. J. Smith, S. Mashhoon, and L. A. Bobek. 2003. Human salivary MUC7 mucin peptides: effect of size, charge and cysteine residues on antifungal activity. Biochem. J. 375:175-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soukka, T., J. Tenovuo, and M. Lenander-Lumikari. 1992. Fungicidal effect of human lactoferrin against Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 69:223-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takao, S., E. H. Smith, D. Wang, C. K. Chan, G. B. Bulkley, and A. S. Klein. 1996. Role of reactive oxygen metabolites in murine peritoneal macrophage phagocytosis and phagocytic killing. Am. J. Physiol. 271:C1278-C1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang, Y. Q., M. R. Yeaman, and M. E. Selsted. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides from human platelets. Infect. Immun. 70:6524-6533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanida, T., R. Fu, T. Hamada, E. Ueta, and T. Osaki. 2001. Lactoferrin peptide increases the survival of Candida albicans-inoculated mice by upregulating neutrophil and macrophage functions, especially in combination with amphotericin B and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Infect. Immun. 69:3883-3890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ueta, E., T. Tanida, and T. Osaki. 2001. A novel bovine lactoferrin peptide, FKCRRWQWRM, suppresses Candida cell growth and activates neutrophils. J. Pept. Res. 57:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vignais, P. V. 2002. The superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase: structural aspects and activation mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:1428-1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voganatsi, A., A. Panyutich, K. T. Miyasaki, and R. K. Murthy. 2001. Mechanism of extracellular release of human neutrophil calprotectin complex. J. Leukoc. Biol. 70:130-134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wada, T., Y. Aiba, K. Shimizu, A. Takagi, T. Miwa, and Y. Koga. 1999. The therapeutic effect of bovine lactoferrin in the host infected with Helicobacter pylori. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 34:238-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakabayashi, H., S. Abe, T. Okutomi, S. Tansho, K. Kawase, and H. Yamaguchi. 1996. Cooperative anti-Candida effect of lactoferrin or its peptides in combination with azole antifungal agents. Microbiol. Immunol. 40:821-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss, J. 1994. Leukocyte-derived antimicrobial proteins. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 1:78-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu, T., S. M. Levitz, R. D. Diamond, and F. G. Oppenheim. 1991. Anticandidal activity of major human salivary histatins. Infect. Immun. 59:2549-2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu, Y. Y., Y. H. Samaranyake, L. P. Samaranyake, and H. Nikawa. 1999. In vitro susceptibility of Candida species to lactoferrin. Med. Mycol. 37:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamori, T., O. Inanami, H. Nagahata, Y. Cui, and M. Kuwabara. 2000. Roles of p38 MAPK, PKC and PI3-K in the signaling pathways of NADPH oxidase activation and phagocytosis in bovine polymorphonuclear leukocytes. FEBS Lett. 467:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]