Abstract

The currently available anti-Toxoplasma agents have serious limitations. This systematic review was performed to evaluate drugs and new compounds used for the treatment of toxoplasmosis. Data was systematically collected from published papers on the efficacy of drugs/compounds used against Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) globally during 2006–2016. The searched databases were PubMed, Google Scholar, Science Direct, ISI Web of Science, EBSCO, and Scopus. One hundred and eighteen papers were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review, which were both in vitro and in vivo studies. Within this review, 80 clinically available drugs and a large number of new compounds with more than 39 mechanisms of action were evaluated. Interestingly, many of the drugs/compounds evaluated against T. gondii act on the apicoplast. Therefore, the apicoplast represents as a potential drug target for new chemotherapy. Based on the current findings, 49 drugs/compounds demonstrated in vitro half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of below 1 μM, but most of them were not evaluated further for in vivo effectiveness. However, the derivatives of the ciprofloxacin, endochin-like quinolones and 1-[4-(4-nitrophenoxy) phenyl] propane-1-one (NPPP) were significantly active against T. gondii tachyzoites both in vitro and in vivo. Thus, these compounds are promising candidates for future studies. Also, compound 32 (T. gondii calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 inhibitor), endochin-like quinolones, miltefosine, rolipram abolish, and guanabenz can be repurposed into an effective anti-parasitic with a unique ability to reduce brain tissue cysts (88.7, 88, 78, 74, and 69%, respectively). Additionally, no promising drugs are available for congenital toxoplasmosis. In conclusion, as current chemotherapy against toxoplasmosis is still not satisfactory, development of well-tolerated and safe specific immunoprophylaxis in relaxing the need of dependence on chemotherapeutics is a highly valuable goal for global disease control. However, with the increasing number of high-risk individuals, and absence of a proper vaccine, continued efforts are necessary for the development of novel treatment options against T. gondii. Some of the novel compounds reviewed here may represent good starting points for the discovery of effective new drugs. In further, bioinformatic and in silico studies are needed in order to identify new potential toxoplasmicidal drugs.

Keywords: Toxoplasma gondii, toxoplasmosis, drugs, compounds, in vitro, in vivo

Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii), an obligate intracellular, parasitic protozoan, is the etiologic agent of toxoplasmosis. About 30–50% of the world population is infected with the parasite, and it is the most prevalent infection among humans (Tenter et al., 2000; Flegr et al., 2014). Worldwide, over 1 billion people are estimated to be infected with T. gondii (Hoffmann et al., 2012). Its prevalence in some countries is high (e.g., Brazil, 77.5%; Sao Tome and Principe, 75.2%; Iran, 63.9%; Colombia, 63.5%; and Cuba, 61.8%) (Pappas et al., 2009). The annual incidence of congenital toxoplasmosis was estimated to be 190,100 cases globally (Torgerson and Mastroiacovo, 2013).

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 22.5% of the population 12 years and older have been infected with Toxoplasma with 1.1 million new infections each year, making it the second most common cause of deaths due to foodborne diseases (an estimated 327 deaths) and the fourth leading cause of hospitalizations attributable to foodborne illness (an estimated 4428 hospitalizations). Also, an estimated 400–4000 infants are born with congenital toxoplasmosis in the United States each year (Jones et al., 2014).

T. gondii has three infectious stages of sporozoites (in oocysts), tachyzoites (rapidly multiplying form), and bradyzoites (tissue cyst form). Among them, tachyzoites are responsible for clinical manifestations and the acute phase of the disease. They are susceptible to the immune response of the host and to drug action. The resistant cyst form of the parasite is resistant to both the immune system and drugs (Hill and Dubey, 2002).

Acute toxoplasmosis in healthy individuals is usually subclinical and asymptomatic, but may lead to chronic infection. However, toxoplasmosis can lead to great morbidity and mortality rates in imunocompromised or congenitally infected individuals (Dubey and Jones, 2008; Ahmadpour et al., 2014). In AIDS patients, presence of the parasite causes necrotizing encephalitis and focal cerebral lesions in the central nervous system (CNS) from primary or recrudescent infection. In immunocompetent patients, latent toxoplasmosis occurs with the formation of cysts principally in the CNS (Martins-Duarte et al., 2006).

In the recent years, the development of well-tolerated and safe specific immunoprophylaxis against toxoplasmosis is a highly valuable goal for global disease control (Lim and Othman, 2014). Immunotherapeutics strategies for improving toxoplasmosis control could either be a vaccine which would induce strong protective immunity against toxoplasmosis, or passive immunization in cases of disease recrudescence. In the last few years, much progress has been made in vaccine research on DNA vaccination, protein vaccination, live attenuated vaccinations, and heterologous vaccination; while there were few candidates on passive immunization. New vaccine candidates have been tested, including in particular proteins from T. gondii ROP, MIC, and GRA organelles, multi-antigen vaccines, novel adjuvants but until now the researches could not access to a proper vaccine for prevention of toxoplasmosis in human (Zhang et al., 2013, 2015).

The recommended drugs for treatment or prophylaxis of toxoplasmosis are pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine. Unfortunately, these drugs have side effects such as neutropenia, severe drop of platelet count, thrombocytopenia, leucopenia, elevation in serum creatinine and serum liver enzymes, hematological abnormalities, and hypersensitivity reactions (Bosch-Driessen et al., 2002; Silveira et al., 2002; Schmidt et al., 2006). In addition, other drugs, such as azithromycin, clarithromycin, spiramycin, atovaquone, dapsone, and cotrimoxazole (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), have been used for clinical toxoplasmosis. However, these drugs are poorly tolerated and have no effect on the bradyzoite form (Araujo and Remington, 1992; Petersen and Schmidt, 2003; Serranti et al., 2011).

In a clinical trial, 24% of sera positive women treated with spiramycin and pyrimethamine plus sulfadoxine combination delivered Toxoplasma infected infants in France (Bessières et al., 2009). Spiramycin monotherapy can be effective during the early stage of pregnancy to prevent prenatal transmission (Julliac et al., 2010). More than 50% of patients treated with spiramycin retained T. gondii DNA in blood and remained infected (Habib, 2008).

In recent years, studies have focused on finding safe drugs with novel mechanisms of action against T. gondii. Accordingly, there is an urgent need to evaluate new drugs based on novel and innovative therapeutic strategies against T. gondii that are both efficacious and nontoxic for humans (Rodriguez and Szajnman, 2012; Vanagas et al., 2012; Angel et al., 2013). Therefore, the goal of the present systematic review was to retrieve published studies related to in vitro and in vivo evaluation of drugs and compounds for the treatment of toxoplasmosis (2006–2016) in order to prepare comprehensive data for designing more accurate investigations in future.

Methodology

This review followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009).

Literature search, study selection, and data extraction

English databases, including PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Google Scholar, ISI Web of Science, and EBSCO, were systematically searched for papers on in vitro and in vivo evaluation of anti-Toxoplasma activities of drugs and compounds, published worldwide, from 2006 to 2016. The keywords included were: “Toxoplasmosis,” “T. gondii,” “Anti-Toxoplasma,” “Drug,” “Anticoccidial,” “Treatment,” “In vitro,” “In vivo,” and “Compound.”

Papers written in English were selected. Gray literature and abstracts of articles which were published in congresses were not explored. In addition, in order to avoid missing any articles, whole references of the papers were meticulously hand-searched. Among English articles found with the mentioned strategies, full text papers that used laboratory method both in vitro and in vivo were included.

Also, studies with at least one of the following criteria were excluded: (1) studies that were not relevant; (2) articles not available in English; (3) studies on treatments for ocular infection; (4) articles that were of review or descriptive study type; (5) articles which contained no eligible data; (6) case series reports; (7) the data were duplicated from other studies or we were unable to obtain them; (8) those that were on efficacy of anti-T. gondii medicines in humans; and (9) any drug with an IC50 value > 10 μM.

Data collection

All the experimental studies that were carried out to evaluate the efficacy of either drugs or compounds against T. gondii both in vitro and in vivo were included, and replicates were excluded. The inclusion criteria for selection of in vitro studies were important information about medication used for the experiments, type of cells used for culture, identification of the Toxoplasma strain, laboratory methods used for assessing drug activities, and main results comprising of the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50). We reported in vivo studies used animal models, Toxoplasma strain, route of infection, the treatment schedule (dosage, route of administration, duration of treatment), the criteria for assessing drug activity (mainly survival for acute toxoplasmosis, histology, and brain cyst burdens for chronic infection), and the main results.

Results

Analysis of the included literature

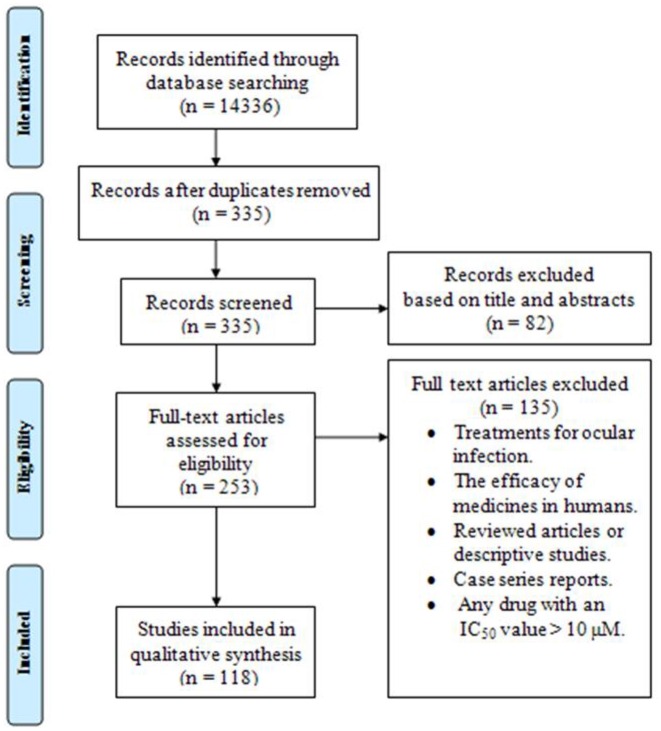

A total of 118 papers (83 studies in vitro, 59 in vivo, 27 both in vitro and in vivo) published from 2006 to 2016, were included in the systematic review. Figure 1 briefly shows the search process in this systematic review article.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram of the search strategy, study selection, and data management procedure of in vitro and in vivo activities of anti-Toxoplasma drugs and compounds (2006–2016).

Mechanisms of action

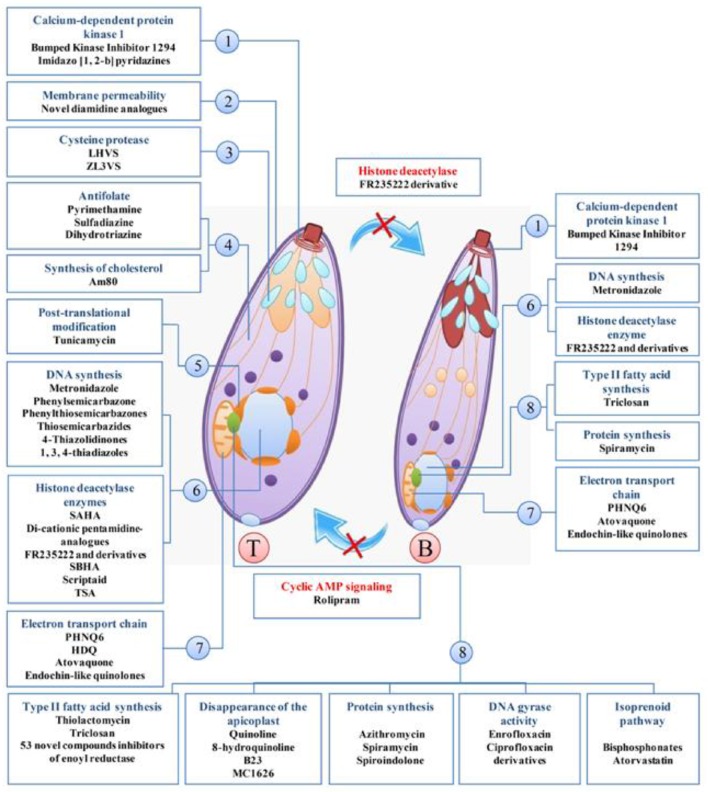

In the current systematic review, 80 clinically available drugs (Table 1) and several new compounds with more than 39 pathways/ mechanisms of action were evaluated against T. gondii in both in vitro and in vivo studies. Several target based drug screens were also identified against T. gondii include mitochondrial electron transport chain, calcium-dependent protein kinase 1, type II fatty acid synthesis, DNA synthesis, DNA replication, etc. (Table 2). Also, drugs/compounds with known mechanisms of action on life stages of T. gondii are shown in Figure 2. Our collective data indicated that many of the drugs/ compounds evaluated against T. gondii act on the apicoplast. Therefore, the apicoplast represents as a potential drug target for new chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Clinically available drugs/compounds evaluated against T. gondii in vitro and in vivo studies.

| Common clinical uses | Drugs/compounds | References |

|---|---|---|

| Antiprotozoal agents | Bisphosphonates | Baramee et al., 2006; Ferreira et al., 2006; Rajapakse et al., 2007; Strobl et al., 2007; Leepin et al., 2008; Shubar et al., 2008; Liesen et al., 2010; Aquino et al., 2011; Franco et al., 2011; Martins-Duarte et al., 2011; Chew et al., 2012; Asgari et al., 2013; Bilgin et al., 2013; Gomes et al., 2013; Gaafar et al., 2014; da Silva et al., 2015; El-Zawawy et al., 2015a,b |

| Diamidine analogs | ||

| Spiramycin (Rovamycin) | ||

| Thiosemicarbazides | ||

| 4-thiazolidinones | ||

| 1,3,4-thiadiazoles | ||

| Naphthalene-sulfonyl-indole | ||

| Thiosemicarbazone | ||

| Phenylsemicarbazone | ||

| Ivermectin | ||

| Silver nanoparticles | ||

| Novel ferrocenic atovaquone derivatives | ||

| Triclosan | ||

| Triclosan liposomal nanoparticles | ||

| Metronidazole | ||

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | ||

| Naphthoquinone | ||

| PHNQ6a | ||

| Novel azasterols | ||

| Apicidin | ||

| Antimalarial agents | Pyrimethamine | Meneceur et al., 2008; Mui et al., 2008; Doggett et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2014; Jain et al., 2015 |

| Atovaquone | ||

| Triazine JPC-2067-B | ||

| Spiroindolone | ||

| Endochin-like quinolones | ||

| Halofuginone | ||

| Antibacterial agents | Sulfadiazine | Meneceur et al., 2008; Costa et al., 2009; Barbosa et al., 2012; Payne et al., 2013; Castro-Filice et al., 2014; Gaafar et al., 2014; Martins-Duarte et al., 2015 |

| Azithromycin | ||

| Enrofloxacin | ||

| Fusidic acid | ||

| Ciprofloxacin | ||

| Chitosan | ||

| Antiretroviral agents | Atazanavir | Monzote et al., 2013 |

| Fosamprenavir | ||

| Indinavir | ||

| Nelfinavir | ||

| Ritonavir | ||

| Saquinavir | ||

| Anticoccidial agents | NPPPb | Kul et al., 2013; Choi et al., 2014; Oz, 2014a,b |

| Diclazuril | ||

| Toltrazuril | ||

| Antihelminthic agents | Niclosamide | Fomovska et al., 2012; Galván-Ramírez et al., 2013 |

| Nitazoxanide | ||

| Antifungal agents | Itraconazole | Martins-Duarte Edos et al., 2008; Martins-Duarte et al., 2010, 2013; Gaafar et al., 2014 |

| Fluconazole | ||

| Chitosan | ||

| Anticancer agents | SAHAc | Strobl et al., 2007; Portes Jde et al., 2012; Leyke et al., 2012; Barna et al., 2013; Kadri et al., 2014; de Lima et al., 2015; Eissa et al., 2015; Opsenica et al., 2015; Dittmar et al., 2016 |

| Pterocarpanquinone | ||

| Ruthenium complexes | ||

| Quinoline derivatives 4-aminoquinoline | ||

| 4-piperazinylquinoline analogs | ||

| Miltefosine | ||

| Tetraoxanes | ||

| Gefitinib | ||

| 3-bromopyruvate | ||

| Tamoxifen | ||

| Immunosuppressants agents | Auranofin | Ghaffarifar et al., 2006; Wei et al., 2007; Andrade et al., 2014; Ihara and Nishikawa, 2014 |

| Am80 | ||

| Betamethasone | ||

| Pyridinylimidazole | ||

| Imidazopyrimidine | ||

| Immunomodulators agents | Rolipram | Afifi and Al-Rabia, 2015 |

| Immunoregulatory agents | Levamisole | Köksal et al., 2016 |

| Antipsychotic agents | Aripiprazole | Saraei et al., 2015 |

| Antioxidant agents | Resveratrol | Bottari et al., 2015 |

| Antischizophrenic agents | Haloperidol | Goodwin et al., 2011; Fond et al., 2014; Saraei et al., 2016 |

| Clozapine | ||

| Fluphenazine | ||

| Trifluoperazine | ||

| Thioridazine | ||

| Amisulpride | ||

| Cyamemazine | ||

| Levomepromazine | ||

| Loxapine | ||

| Olanzapine | ||

| Risperidone | ||

| Tiapride | ||

| Moodstabilizing agents | Valproate | Fond et al., 2014 |

| Anti hypertensive agents | Guanabenz | Benmerzouga et al., 2015 |

| Anti hypertensive and irregular heart rate agents | Propranolol | Montazeri et al., 2015, 2016 |

2-hydroxy-3-(1′-propen-3-phenyl)-1,4-naphthoquinone.

(4-nitrophenoxy) phenyl] propane one.

Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid.

Table 2.

Drugs/compounds with pathways/ mechanisms of action against T. gondii.

| Pathway/mechanism of action | Drugs/compounds | References |

|---|---|---|

| Electron transport chain | PHNQ6*a | Baramee et al., 2006; Ferreira et al., 2006, 2012; Saleh et al., 2007; Meneceur et al., 2008; Bajohr et al., 2010; Doggett et al., 2012; Kul et al., 2013; de Lima et al., 2015 |

| HDQ*b | ||

| Atovaquone* | ||

| Endochin-like quinolones* | ||

| Ferrocenic atovaquone derivatives | ||

| Naphthoquinones | ||

| Toltrazuril | ||

| 3-Bromopyruvate | ||

| Sterol biosynthesis | Novel quinuclidine (ER119884, E5700) | Martins-Duarte et al., 2006 |

| Synthesis of cholesterol | Am80* | Ihara and Nishikawa, 2014 |

| Antifolate | Pyrimethamine* | Meneceur et al., 2008; Mui et al., 2008; Martins-Duarte et al., 2013 |

| Sulfadiazine* | ||

| Dihydrotriazine* | ||

| (JPC-2067-B, JPC-2056) | ||

| Calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 | 1 NM-PP1* | Sugi et al., 2011; Doggett et al., 2014; Moine et al., 2015b; Vidadala et al., 2016 |

| Bumped Kinase Inhibitor 1294* | ||

| Imidazo [1,2-b] pyridazines* | ||

| Compound 32* | ||

| Human mitogen-activated protein kinase | Pyridinylimidazole* | Wei et al., 2007 |

| Imidazopyrimidine* | ||

| Nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase (NTPase) | 2-(Naphthalene-2-γlthiol)-1H indole* | Asgari et al., 2013, 2015 |

| Isoprenoid pathway | 2- alkylaminoethyl- 1,1- bisphosphonic acids* | Shubar et al., 2008; Szajnman et al., 2008; Li et al., 2013 |

| Newly synthesized bisphosphonates* | ||

| Atorvastatin* | ||

| Type II fatty acid synthesis | Thiolactomycin* | Martins-Duarte et al., 2009; Tipparaju et al., 2010; El-Zawawy et al., 2015a,b |

| 53 novel compounds* | ||

| Inhibitors of enoyl reductase | ||

| Triclosan and triclosan liposomal* | ||

| Protein synthesis | Azithromycin* | Costa et al., 2009; Franco et al., 2011; Chew et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2014; Palencia et al., 2016 |

| Spiramycin* | ||

| Spiroindolone | ||

| 3-aminomethyl benzoxaborole (AN6426) | ||

| Disappearance of the Apicoplast | Quinoline derivatives* | Smith et al., 2007; Kadri et al., 2014 |

| (MC1626, quinoline, 8-hydroquinoline and B23) | ||

| Histone deacetylase enzyme | SAHA*c | Strobl et al., 2007; Maubon et al., 2010; Kropf et al., 2012 |

| SBHA*d | ||

| Scriptaid* | ||

| Trichostatin A* | ||

| Di-cationic pentamidine-analog* | ||

| FR235222, FR235222 derivative* | ||

| DNA synthesis | Metronidazole* | Liesen et al., 2010; Chew et al., 2012; Gomes et al., 2013 |

| Phenylsemicarbazone* | ||

| Phenylthiosemicarbazones* | ||

| Thiosemicarbazides* | ||

| 4-Thiazolidinones* | ||

| 1,3,4-thiadiazoles* | ||

| Cyclic AMP signaling pathways | Rolipram* | Afifi et al., 2014; Afifi and Al-Rabia, 2015 |

| Post-translational modification by N-linked glycosylation of proteins | Tunicamycin* | Luk et al., 2008 |

| Membrane permeability | Novel diamidine analog* | Leepin et al., 2008 |

| Microfilament functional | Cromolyn sodium | Endeshaw et al., 2010; Rezaei et al., 2014; Montazeri et al., 2015, 2016 |

| Ketotifen | ||

| Propranolol | ||

| Oryzalin analogs | ||

| Micronemal secretion pathway, cysteine protease | Peptidyl vinyl sulfone compounds* (LHVS and ZL3VS) | Teo et al., 2007 |

| Immuno-regulatory | Levamisole* | Köksal et al., 2016 |

| Translational control | Guanabenz* | Payne et al., 2013; Benmerzouga et al., 2015; Jain et al., 2015 |

| Fusidic acid | ||

| Halofuginone* | ||

| DNA gyrase activity, transcription | Enrofloxacin | Barbosa et al., 2012; Martins-Duarte et al., 2015 |

| Ciprofloxacin derivatives* | ||

| Thioredoxin reductase | Auranofin | Andrade et al., 2014 |

| Topoisomerases I and II HSP90 protein | Harmane, norharmane, and harmine | Alomar et al., 2013 |

| Metabolism of neurotransmitters in the brain | Resveratrol | Bottari et al., 2015 |

| Effect on the liver biochemical parameters | ATT-5126 and KH-0562 | Choi et al., 2014 |

| Vascular ATP synthase subunit C and/or methyltransferase | NPPP | Choi et al., 2015 |

| Sterol biosynthesis enzyme-sterol methyl transferase. | 22, 26-azasterol and 24, 25-(R, S)- epiminolanosterol | Martins-Duarte et al., 2011 |

| Downregulates expression of serine/threonine protein phosphatase | Diclazuril | Oz, 2014a,b |

| Ergosterol synthesis | Fluconazole | Martins-Duarte Edos et al., 2008; Martins-Duarte et al., 2013 |

| Itraconazole | ||

| Interruption of mitosis | Trifluralin | Wiengcharoen et al., 2007 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | Niclosamide | Fomovska et al., 2012 |

| Apocynin-dependent pathway | NSC3852 | Strobl et al., 2009 |

| Phospholipid metabolism | Miltefosine | Eissa et al., 2015 |

| Quinone oxidoreductase expression | Nitaxozanide | Galván-Ramírez et al., 2013 |

| Kinase inhibitors | Small-molecules | Kamau et al., 2012 |

| Tyrosine kinase | Gefitinib | Yang et al., 2014 |

| Crizotinib | ||

| Adenosine kinase in the purine salvage pathways | N6-benzyladenosine analog* | Kim et al., 2007; Szajnman et al., 2008 |

| Purine nucleoside phosphorylase | 3-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,2,4-triazole-5-thione | Dzitko et al., 2014b |

| Damage on the microneme proteins | 7-nitroquinoxalin-2-ones (VAM2-2) | Fernández et al., 2016 |

Drugs/compounds with known pathway/mechanisms of action gainst T. gondii.

2-hydroxy-3-(1′-propen-3-phenyl)-1,4-naphthoquinone.

1-hydroxy-2-dodecyl-4 (1H) quinolone.

Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid.

Suberic bishydroxamic acid.

Figure 2.

Drugs/compounds with known mechanisms of action on life stages of T. gondii, tachyzoites (T), and bradyzoites (B). 1, apical end; 2, Cell membrane; 3, microneme; 4, cytosol; 5, endoplasmic reticulum; 6, core; 7, mitochondria; 8, apicoplast.

The investigated strains

T. gondii has three main clonal lineages in population structure; type I (including a highly virulent RH strain), Type II (including ME49 and PRU, avirulent strains), and Type III (including avirulent strains like NED), which is correlated with virulence expression in mice (Howe and Sibley, 1995).

In vitro and in vivo screening methods were used of type I T. gondii (mostly RH strain; 76 studies in vitro, and 36 in vivo). Because type I RH strain is highly virulent in mice, causing 100% mortality, but types II and III are relatively less virulent. Although in some studies, ME49 (7 studies in vitro, and 17 in vivo), Prugniaud, EGS, and VEG strains were used, which showed that the outcome of infections depends on the challenge dose and on the genotype of the host (Szabo and Finney, 2016). Details about the investigated strains in vitro and in vivo are shown in Tables 3, 4, respectively.

Table 3.

Summary of in vitro studies evaluated the anti-Toxoplasma activity of drugs/compounds.

| No | Drug | Strain | Cells | Culture | Evaluation | Main results | Effectivity | Positive control | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Two novel quinuclidine (ER119884, E5700) | RH | LLCMK2 | 24, 48 h | IC50 valuesa | IC50 ER119884, E5700 = 0.66, 0.23 μM | Effective | Sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine | Martins-Duarte et al., 2006 |

| 2 | Fourteen novel ferrocenic atovaquone derivatives | 76K, PLK, A to R | HFF | 48 h | IC50 values | IC50 2d, 2e, 2f = 5.0, 2.5, 6.25 μM | Effective 2d, 2e, 2f | – | Baramee et al., 2006 |

| 3 | Betamethasone and IFN-γb | RH | Hela | 24, 48, 72 h | Counting the number of tachyzoites | High number of plaques was seen in group with 40 μg/ml of betamethasone. | Betamethasone not effective, IFN–γ effective | – | Ghaffarifar et al., 2006 |

| 4 | Suberoylanilide hydroxamic, suberic bishydroxamic acid, scriptaid, trichostatin A | RH | HS68 HFF | 48, 72 h | IC50 values | IC50 scriptaid = 0.039 μM | Scriptaid was the most effective | – | Strobl et al., 2007 |

| 5 | RWJ67657, RWJ64809c, RWJ68198d | RH, ME49 | HFF | 48 h | IC50 values | RWJ67657 was at least as potent as RWJ68198, SB203580, or SB202190 in reducing of T. gondii replication | RWJ67657, SB203580 effective | – | Wei et al., 2007 |

| 6 | Novel drug compounds (A–I) (B,F,G,H) (trifluralin analogs) | RH | Vero | 72 h | MTT assaye, crystal violet assay | IC50 drug F = 10 μM | Drugs F was the most effective | – | Wiengcharoen et al., 2007 |

| 7 | 1-hydroxy-2-dodecyl-4(1H) quinolone (HDQ) | RH | HFF | 24 h | Replication rate determined | IC50 HDQ = 0.0024 ± 0.0003 μM | Effective | – | Saleh et al., 2007 |

| 8 | Quinoline derivative MC1626 | RH | HFF | 24 h | Standard [3H]uracil uptake and plaque assays | 100 μM reducing growth | Effective | – | Smith et al., 2007 |

| 9 | N6-benzyladenosine analogs | RH | HFF | 24 h | MTT assay | IC50 N6-(2,4-dimethoxybenzyl) Adenosine = 8.7 ± 0.6 μM, exhibited the most favorable activity | Effective | Sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine | Kim et al., 2007 |

| 10 | Fluorine-containing aryloxyethyl thiocyanate derivatives | RH | HFF | 24 h | IC50 values | IC50 compounds 1 and 3 = 2.80 and 3.99 μM | Effective | Atovaquone | Liñares et al., 2007 |

| 11 | LHVS, ZL3VSf | RH or 2F1 | HFF | 45 min | B galg, Red/green invasion assay, SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting, gliding motility assay | IC50 LHVS and ZL3 VS = 10 and 12.5 μM | Effective | 3,4-dichloroisocoumarin | Teo et al., 2007 |

| 12 | 1,25(OH) 2D3 | RH | MICc12 | 72 h | Trypan blue assay | Ruled out any toxic effects of 1,25(OH) 2D 3 for T. gondii | Effective | – | Rajapakse et al., 2007 |

| 13 | Tunicamycin | RH | HFF | 2, 24, or 48 h | Fluorescence and electron microscopy | N-Glycosylation is completely inhibited by treatment of parasites with tunicamycin | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Luk et al., 2008 |

| 14 | Novel diamidine analogs | RH | Vero HFF | 2 or 3 days | IC50 values, Q-PCRh | IC50 DB750, DB786 = 0.16, 0.22 μM | Effective | – | Leepin et al., 2008 |

| 15 | Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and atovaquone | 17 strains T. gondii | THP-1 MRC-5 | 7 days | IC50, real-time PCR | IC50 pyrimethamine = 0.0002, 0.01 μM | Effective | – | Meneceur et al., 2008 |

| IC50 atovaquone = 0.0001, 0.00005 μM | |||||||||

| IC50 sulfadiazine = 0.01, 0.07 μM for | |||||||||

| 13 strains and were > 0.1 μM for three strains | |||||||||

| 16 | Novel triazine JPC-2067-B | RH | HFF | 3 days | Liquid scintillation counting | IC50 JPC-2067-B = 0.02 μM, | Effective | – | Mui et al., 2008 |

| IC90 JPC-2067-B = 0.05 μM | |||||||||

| 17 | Newly synthesized bisphosphonates (15 new compounds) | RH | Mouse macrophages (J 744A.1) | 24, 48 h | MTT assay, flow cytometry | 91A and 282A showed moderate and low toxicity (cell viability between 70% and 100%) | Effective | – | Shubar et al., 2008 |

| 18 | 2-alkylaminoethyl- 1,1-bisphosphonic acids | RH | HFF | Daily | IC50 values, radiometric assay | IC50 compound 19 = 2.6 μM | Compound 19 was very effective | . | Szajnman et al., 2008 |

| 19 | Itraconazole | RH | LLCMK2 | 24 or 48 h | IC50 values, TEMi analysis | IC50 = 0.11, 0.05 μM for 24, 48 h | Effective | – | Martins-Duarte Edos et al., 2008 |

| 20 | Thiolactomycin analogs (8 new compounds) | RH | LLCMK2 | 24, 48 h | IC50 values, Lipid extraction, chromatographic analysis | IC50 compounds = 1.6-29.4 μM | Compound 5 was very effective | Sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine | Martins-Duarte et al., 2009 |

| 21 | NSC3852j | RH | HS 68 HFF | 2 h | SYBR green assay, MTS assay, ROS assay, NO assays | EC50 NSC3852 = 0.08 μM, | NSC3852, NSC74949 were the most effective | – | Strobl et al., 2009 |

| EC50 NSC74949 = 0.6 μM | |||||||||

| 22 | FR235222, FR235222 derivative compounds (W363, W371, W399, W406, W425) | RH, PRU (type II) | HFF | 24 h | EC50 determination, Western blot analysis, immunofluorescence microscopy | 100% altered cysts 24 h after treatment with the lowest concentration of FR235222 | Effective | – | Maubon et al., 2010 |

| 23 | Thiosemicarbazides, 4-thiazolidinones and 1,3,4-thiadiazoles | RH | Vero | 24 h | Mean number of intracellular parasitesa, LD50k | A significant decrease in the percentage of infected cells and in the mean number of tachyzoites per cell from the concentrations of 0.1, 1, 10 mM | Effective | Hydroxyurea, sulfadiazine | Liesen et al., 2010 |

| 24 | FLZl and ITZm | RH | LLCMK2 | 24, 48 h | IC50 values | IC50 FLZ = 8.9, 3.1 μM after 24, 48 h | Effective | Sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine | Martins-Duarte et al., 2010 |

| IC50 ITZ = 0.1, 0.05 μM for 24, 48 h | |||||||||

| 25 | 1-Hydroxy-2-Alkyl-4(1H) Quinolone Derivatives | RH (type I) | HFF | 24 h | IC50 values | IC50 compound A, B = 0.0004, 0.0008 μM | Effective | Atovaquone | Bajohr et al., 2010 |

| 26 | Oryzalin Analogs | RH | HFF | 8 day 26 h | Plaque assay, Immunofluorescence assay, IC50 values | IC50 18b = 0.03 μM | Effective | – | Endeshaw et al., 2010 |

| 27 | 53 novel compounds (Inhibitors of Enoyl reductase) | RH | HFF | 3 days | IC50 values | IC50 compounds 2, 19 = 0.04, 0.02 μM, | Compounds 2, 19, 39 greatest effect | – | Tipparaju et al., 2010 |

| IC50 compounds 39 less active | |||||||||

| 28 | Haloperidol, clozapine, fluphenazine, trifluoperazine, thioridazine | RH | HFF | 48 h | IC50 values | IC50 fluphenazine, thioridazine, trifluoperazine = 1, 1.2, and 3.8 μM | Fluphenazine, thioridazine, trifluoperazine were effective | – | Goodwin et al., 2011 |

| 29 | Azithromycin, spiramycin | RH | Bewo cell line | 24 h | MTT assay, measurement of Th1/Th2 | Increase TNF-an, IL-10, IL-4 production, but decreased IFN-γ | Effective | – | Franco et al., 2011 |

| 30 | Novel azasterols | RH ME49 | LLCMK2 | 24 or 48 h | IC50 values, imunofluorescence assays | IC50 compounds 1, 2, 3 = 0.8–4.7 μM | Compound 3 was the most effective | – | Martins-Duarte et al., 2011 |

| 31 | Ciprofloxacin derivatives | RH | LLC-MK2 | 24 or 48 h | IC50, MTS assay | IC50 compounds 2, 4, 5= 0.42, 1.24, and 0.46 μM | Effective | – | Dubar et al., 2011 |

| 32 | 2-hydrazolyl-3-phenyl-5-(4-nitrobenzylidene)-4-thiazolidinone substituted | RH | Vero | 24 h | LD50 values | LD50 = 0.5, 10 mM | Effective | Hydroxyurea, Sulfadiazine | Aquino et al., 2011 |

| 33 | Nanoparticles | RH (CAT-GFP) | Macrophages J 774-A1 | 3 day | HPLCo: flow cytometry | Cap.85% observed maximum in Toxoplasmosis therapy efficiency | Effective | – | Leyke et al., 2012 |

| 34 | Enrofloxacin | RH | HFF | 72 h | MTT assays | Enrofloxacin resulted in a significant inhibition of the percentage of infected cells by the parasite (58.72%) | Effective | Sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine | Barbosa et al., 2012 |

| 35 | ELQ-271 and ELQ-316q | 2F | HFF | 4 days | Host-cell toxicity | IC50 ELQ-271, ELQ-316 = 0.0001, and 0.000007 μM | Effective | Atovaquone | Doggett et al., 2012 |

| 36 | Pterocarpanquinone | RH | LLCMK2 | 24 or 48 h | Direct counts, viability, imunofluorescence assays | IC50= 2.5 μM | Effective | – | Portes Jde et al., 2012 |

| 37 | New naphthoquinones and an alkaloid | RH, EGS | HFF | 48 h | MTT assays | IC50 QUI-5, and QUI-6r = 69.35, and 172.81 μM | Effective | Atovaquone, Sulfadiazine | Ferreira et al., 2012 |

| 38 | Spiramycin coadministered with metronidazole | ME49 | Vero E6 | 1 week | Numbers of cysts and tachyzoites | Spiramycin reduced in vitro reactivation, metronidazole alone did not have significant effect | Effective | – | Chew et al., 2012 |

| 39 | Di-cationic pentamidine-analogs | RH ME49 | HFF | 72 h | Cytotoxicity assays | IC50 arylimidamide DB745 = 0.11, 0.13 μM (tachyzoites of Rh, Me49) | Effective | Atovaquone | Kropf et al., 2012 |

| 40 | Small-Molecule (n=527) | Strains 5A10 (type III strain) | HFF | 72 h | Luciferasebased assay, Host cell viability, electron microscopy, invasion, motility assays | EC50 s for the 14 compounds = 0.14–8.7 μM | 14 compounds effect | – | Kamau et al., 2012 |

| 41 | Salicylic acids (39 compounds) | RH, RH-YFP, and ME49 | HFF | 1 h | [3H]-Uracil incorporation and YFP Fluorescence assay | 3i, 3j, 7a, 14a, and 14b were active at low nanomolar concentrations | Effective | Pyrimethamine, Sulfadiazine | Fomovska et al., 2012 |

| 42 | FLZ combined with sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine | RH | LLCMK2 | 24 h | IC50 values and MTS assay | IC50 FLZ = 8.4 ± 1.2, IC50 sulfadiazine/pyrimethamine, pyrimethamine = 8.7 ± 0.8 μM | Effective | – | Martins-Duarte et al., 2013 |

| 43 | Harmane, Norharmane (β-carboline alkaloids) | RH | Vero HFF | 1, 24 h | Parasite invasion and replication rate | harmane and harmine showed 2.5- to 3.5-fold decrease in the invasion rates at doses of 40 μM, norharmane 2.5 μM | Effective | Sulfadiazine | Alomar et al., 2013 |

| 44 | Fusidic acid | Prugniaud | HFF | 7 days | Lytic plaques counted | IC50 = 7.7 μM, decreased the number of T. gondii plaques in a dosedependent manner | Effective | – | Payne et al., 2013 |

| 45 | Two naphthalene-sulfonyl-indole compounds | RH | – | 1.5 h | Stained by PI, analyzed by FACS | LD50 compound A, B = 62, 800 μmol | Effective | Saponin | Asgari et al., 2013 |

| 46 | (Benzaldehyde)-4-phenyl-3- thiosemicarbazone, (benzaldehyde)-(4 or 1)- phenylsemicarbazone (9 compounds) | RH | Vero | 24 h | Cytotoxicity, number of intracellular parasites | LD50 compound 8 = 0.3 mM, reduced the number of intracellular parasites by 82 % in a concentration of 0.01 mM | Effective | Sulfadizine | Gomes et al., 2013 |

| 47 | Ivermectin and sulphadiazine | RH | Hep- 2 | 24, 48, 72 h | IC50, invert microscopy, ELISA assay | IC50 ivermectin and sulphadiazine = 0.2, and 29.1 μM | Effective | – | Bilgin et al., 2013 |

| 48 | Novel ruthenium complexes | RH | HFF | 72 h | cytotoxicity assessment, TEM | EC50 compounds 16, 18 = 18.7, 41.1 nM | Compounds 16, and 18 effective | – | Barna et al., 2013 |

| 49 | Atazanavir, fosamprenavir, indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, and saquinavir | RH | Macrophages Swiss Webster | 48 h | IC50 determination, MTT assay | IC50 atazanavir ritonavir, and saquinavir = > 1 μM | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Monzote et al., 2013 |

| IC50 fosamprenavir, and nelfinavir = > 5 μM | |||||||||

| 50 | Atorvastatin | RH | HFF | 8 days | IC50 values | IC50 = 50 μM | Effective | – | Li et al., 2013 |

| 51 | Nitaxozanide | RH | Astrocyte | 24,48 h | Immunocytochemical method, microscopic analysis, viability | Nitazoxanide produced 97% T. gondii death in a concentration of 10 mg/mL in 48 h infected astrocytes | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Galván-Ramírez et al., 2013 |

| 52 | Amisulpride, cyamemazine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, levomepromazine, loxapine, olanzapine, risperidone, tiapride, and valproate | RH | HFF | 4 h | Growth inhibition assay | Amisulpride, tiapride and valproate did not have inhibitory activity | Zuclopenthixol, high effective | – | Fond et al., 2014 |

| 53 | Spiroindolone | RH | HFF | 72 h | Fluorescence assays, cytotoxicity assessment | IC50 = 1 μM | Effective | Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine | Zhou et al., 2014 |

| 54 | Auranofin | RH | HFF | 5 days | Invasion and replication assays and plaque assays | TD50 = 8.21 μM, IC50 = 0.28 μM | Effective | Pyrimethamine, Sulfadiazine | Andrade et al., 2014 |

| 55 | Azithromycin | 2 F1 | Placental tissues | 48 h | Production of cytokines and hormones | Increases IL-6 production, reduced secretion of estradiol, progesterone, and HCG + β | Effective | Pyrimethamine, Sulfadiazine, folinic acid | Castro-Filice et al., 2014 |

| 56 | 6-Trifluoromethyl-2-thiouracil (ATT-5126), (KH-0562) | RH | Hela | 24 h | MTS assay, IC50 | IC50 ATT-5126, KH-0562 = 19.7, 32.2 μM | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Choi et al., 2014 |

| CC50 ATT-5126, KH-0562 = 35.4, 56.3 μM | |||||||||

| 57 | Cromolyn sodium and ketotifen | RH | Macrophage monolayer | 24 h | Inhibition rate | After 60 min the best efficacy was observed at 15 μg/ml (78.9 ± 1.70, 91.97 ± 0.37%) | Effective | – | Rezaei et al., 2014 |

| 58 | 200 drug-like and 200 probe-like compounds of Malaria Box | TS-4 (mutant of the RH) | HFF | 24 h | Cytotoxicity assays | Seven compounds with IC50 < 5 μM, SI > 6 | 7 compounds effected | Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine | Boyom et al., 2014 |

| 59 | Am80 | RH, PLK, its recombinants | J 774A.1 | 20 h | Uracil incorporation assay, RT–PCRs, flow cytometry | Am80 inhibited parasite growth by decreasing intracellular accumulation of cholesterol | Effective | – | Ihara and Nishikawa, 2014 |

| 60 | Pyrimethamine –loaded lipid-core nanocapsules | RH | LLC-MK2 | 72 h | MTS assay | TC50 PYR loaded lipid-core nanocapsules = 6.0 μM | Effective | – | Pissinate et al., 2014 |

| 61 | Quinoline derivatives (58 compounds) | 2F | HFF | 4 days | Cytotoxicity assays | IC50 B23 = 0.4 ± 0.03 μM, the most effective compound | 32 compounds effected | – | Kadri et al., 2014 |

| 62 | 74 novel thiazolidin-4-one derivatives | – | HFF | 5 days | Cytotoxicity assays | IC50 derivatives 12 A, 27 A = 0.9, 2.9 μM | Effective | Timethoprim | D'Ascenzio et al., 2014 |

| 63 | Gefitinib and Crizotinib | RH | Hela | 24, 48, 72 h | Counting the number of T. gondii per parasitophorous vacuolar membrane | Gefitinib inhibited the growth of T. gondii over 5 μM whereas Sunitinib did not | Gefitinib effected | Pyrimethamine | Yang et al., 2014 |

| 64 | 1,4-disubstituted thiosemicarbazides | RH | Mouse L929 fibroblasts | 24 h | MTT assay and q-pcr | 1g, 2b, 3d, 3l showed significant anti-parasitic effects | 1 g was very effective | Sulfadiazine | Dzitko et al., 2014a |

| 65 | 3-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,2,4-triazole-5-thione | RH | Mouse L929 fibroblasts | 24 h | IC50 values and q-pcr | IC50 at least 30 times better than that of sulfadiazine | Effective | Sulfadiazine | Dzitko et al., 2014b |

| 66 | 1-[4-(4-nitrophenoxy) phenyl]propane-1-one (NPPP) | RH | Hela | 24 h | CC50, EC50 values | EC50, CC50 = 36.2 ± 0.2, 67.0 ± 0.2 μM | Effective | – | Choi et al., 2015 |

| 67 | C-type lectin from Bothropspauloensis venom | RH | Hela | 24 h | MTT assay, cytokine measurements | MTT assay between 0.195, 12.5 μg/mL MIF, IL-6 productions were increased | Effective | – | Castanheira et al., 2015 |

| 68 | Ciprofloxacin derivatives Compounds (2, 4, 5) | RH | LLCMK2 HFF | 24, 48, 72 h | Immunofluorescence, TEM | Inhibited parasite replication early in the first cycle of infection | Effective | – | Martins-Duarte et al., 2015 |

| 6 h | |||||||||

| 69 | New chiral N-cylsulfonamide bis-oxazolidin-2-ones | RH | MRC-5 | – | IC50 values | IC50 of Mol 1 was less than Mol 2 | Effective | Sulfadiazine | Meriem et al., 2015 |

| 70 | Guanabenz | ME49 Prugniaud | HFF | 32 h | EC50 values | EC50 = 6 μM | Effective | – | Benmerzouga et al., 2015 |

| 71 | 3-Bromopyruvate, Atovaquone | RH | LLC-MK2 | 24, 48 h, or 6 days | Light-microscopic analysis, indirect immunofluorescent assays | 73 and 71% reduction in intracellular parasites after 24, 48 h | Effective | – | de Lima et al., 2015 |

| 72 | Biphenylimidazoazines | RH | HFF | 96 h | EC50 values and fluorescence microscopy assay | EC50 < 1 μM | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Moine et al., 2015a |

| 73 | Halofuginone | RH | HFF | 24 h | EC50 values | EC50 = 0.94 nM | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Jain et al., 2015 |

| 74 | Naphthoquinone derivative | RH | LLC-MK2 | 24, 48 h | IC50 and MTT assay | IC50 LQB 151 = < 1 μM | Effective | – | da Silva et al., 2015 |

| 75 | Aryloxyethyl thiocyanates | RH | Vero | 24 h | Determination of ED50 | ED50 derivatives 15 and 16 = 1.6 μM and 1.9 μM | Effective | – | Chao et al., 2015 |

| 76 | Imidazo [1,2-b] pyridazines derivatives | RH-GFP | HFF | 24 h | Cytotoxicity assay | EC50 16a, 16f = 100, 70 nM | Effective | – | Moine et al., 2015b |

| 77 | Nitrofurantoin | RH | Hela | 24 h | MTS assay | Selectivity = 2.3 | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Yeo et al., 2016 |

| EC50 = 14.7 μM | |||||||||

| 78 | Quinoxalinone derivatives | RH | HEp-2t | 24 h | IC50 values, viability, invasion, and intracellular growth | MIC50 VAM2-2 = 3.3 ± 1.8 μM | VAM2-2 was very effective | – | Fernández et al., 2016 |

| 79 | 1120 compounds | RH-GFP | HFF | 72 h | Parasite invasion, Microneme secretion, Luciferase, and LC3-GFP assays | 94 compounds with IC50 < 5 μM | Tamoxifen effective | – | Dittmar et al., 2016 |

| 80 | 3-aminomethyl benzoxaborole (AN6426) | RH | HFF | 24 h | Determination of EC50 | EC50 = 76.9 μM | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Palencia et al., 2016 |

| 81 | Sulfur-containing linear bisphosphonates | RH, Prugniard | Human fibroblasts (hTert cells) | 5 days | Determination of EC50 | EC50 = 0.11 ± 0.02 μM | Compound 22 was very effective | – | Szajnman et al., 2016 |

| 82 | Fluorine-containing Analogs of WC-9 (4-phenoxyphenoxyethyl thiocyanate) | RH | Vero | 24 h | Determination of EC50 | EC50 3-(3-fluorophenoxy), 3-(4-fluorophenoxy) phenoxyethyl thiocyanates, and 2-[3-(phenoxy)phenoxyethylthio]ethyl-1,1-bisphosphonat = 1.6 4.9 and 0.7 μM | Effective | – | Chao et al., 2016 |

| 83 | 6-(1,2,6,7-tetraoxaspiro[7.11] nonadec-4-yl)hexan-1-ol (N-251) | RH | Human hepatocyte, Huh-7 | 72 h | IC50 values, q-pcr, ultrastructural Change by TEM | LC50 = 1.11 μg/ml | Effective | Sulfadiazine | Xin et al., 2016 |

Half maximal inhibitory concentration.

Interferon gamma.

Pyridinylimidazole.

Imidazopyrimidine.

3− (4, 5−Dimethyl−2−Thiazyl) − 2, 5−Diphenyl−2H−Tetrazoliu Bromide.

Morpholinourea-leucyl-homophenolalaninyl-phenyl-vinylsulfone, N-benzoxycarbonyl-(leucyl) 3-phenyl-vinyl-sulfone.

B galactosidase.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Transmission electron microscopy.

5- nitroso-8-quinolinol.

Lethal Dose, 50%.

Fluconazole.

Itraconazole.

Tumor necrosis factor.

High Performance Liquid Chromatography.

Carriers achieved.

Endochin-like quinolones.

7-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-2-pyrrolidine-[1, 4]-naphthoquinone (QUI-5), 6-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-2-pyrrolidine-[1, 4]-naphthoquinone (QUI-6).

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Human larynx epidermoid carcinoma epithelial cells.

Table 4.

Summary of in vivo studies evaluated the anti-Toxoplasma activity of drugs/ compounds.

| No | Drug | Animal | Strain | Type of infection | Inoculum | Treatment | Assessment of efficacy | Main results | Effectivity | Positive control | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PHNQ6a alone or combined with sulfadiazine | Female Swiss mice | RH EGS P | Acute, chronic | 1000 tachyzoites (ip) 10 brain cysts (orally) | PHNQ6 50 mg/kg/day Sulfadiazine, 40 mg/L | Survival rates, IFATb, and liver histology | Treatment protected at least 70, 90% of mice infected with RH and EGS strains | Effective | Sulfadiazine | Ferreira et al., 2006 |

| 2 | 1, 25(OH) 2D3 | BALB/c | ME49 | Acute | 20 cysts | 0.5 μg/kg/2 days ip | Histopathology, RT-PCRc | Low parasitic burdens were found | Effective | – | Rajapakse et al., 2007 |

| 3 | Pyridinylimidazole (RWJ67657, RWJ64809), imidazopyrimidine (RWJ68198) | Female CBA/J, CD8 / – | RH ME49 | Acute | 1000, 100, and 20 tachyzoites | 3.8, 7.5, 15, 30, or 60 mg/kg i.p | Survival rates | The highest dose (60 mg/kg) significantly improved survival | RWJ67657 effective | – | Wei et al., 2007 |

| 4 | Novel triazine JPC-2067-B | Outbred Swiss Webster | RH | Acute | 10000 tachyzoites i.p | 1.25 mg/kg/day orally | Peritoneal T. gondii burden | Intraperitoneal parasite numbers were reduced | Effective | – | Mui et al., 2008 |

| 5 | Newly synthesized bisphosphonates | NMRI | RH | Acute | 100 000 tachyzoites i.p | 490, 1000, 512, 44.05, and 47.6 μM | Flow cytometry | Therapeutic efficacy was 100% for bisphosphonates 2F, 3B, 18A, 22A, and 30B | Effective | – | Shubar et al., 2008 |

| 6 | Azithromycin, Artemisia annua, spiramycin, SPFA | Females C. callosus | ME49 | Chronic | 20 cysts | Azithromycin (9 mg/24 h), A. annua (1.0 mg/8 h), spiramycin (0.15 mg/8 h) | Morphological, immunohistochemical analyses, mouse bioassay, and PCRd | No morphological changes were seen in the placenta and embryonic tissues from females treated with azithromycin, spiramycin, and SPFA | Azithromycin more effective | – | Costa et al., 2009 |

| 7 | Dihydroartemisinin and azithromycin | Kunming mice | . | Acute | 2 × 103tachyzoites | Dihydroartemisinin and azithromycin 75 and 200 mg/kg | The ultrastructure of tachyzoites | The ultrastructure of tachyzoites was observed in the treatment groups such as edema, enlarged, broken or damaged | Effective | – | Yin et al., 2009 |

| 8 | FLZf and ITZg | Outbred female Swiss | CF1 ME49 | Chronic | 20 cysts of the ME49 orally or i.p | 10,20 mg/kg/day orally | Survival rates and brain cyst burden | ITZ survival of 90, 87% FLZ survival rate of 71, 85% | Effective | Sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine | Martins-Duarte et al., 2010 |

| 9 | HDQh derivatives | Female NMRI, IRF-8 /– | RH ME49 | Acute, chronic | 105 green fluorescent protein, i.p 10 cysts | 32 mg/kg body weight/day | Parasite loads in lungs, livers by qPCRe, and flow cytometry analyses | Derivatives of HDQ had lower parasite concentrations than mice treated with HDQ | Effective | Atovaquone | Bajohr et al., 2010 |

| 10 | FR235222, FR235222 derivative, (W363, W371, W399, W406, W425) | Outbred female Swiss | PRU | Chronic | Living cysts i.p | 200 nM | Presence or absence of cysts in brain was assessed by staining | No cysts were detected in mice inoculated with FR235222-treated | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Maubon et al., 2010 |

| 11 | Azithromycin combined with metronidazole | BALB/c | – | Acutly | 50 tissue cysts orally or i.p | 250, 200 mg/kg/day | Microscopical examination, bioassay were done for brain, and survival rates | Cure rate 100% | Effective | – | H.Al-jader and Al-Mukhtar, 2010 |

| 12 | Novel compounds 2,19 (Inhibitors of Enoyl Reductase) | CD1 | RH | Acute | 2000 | 10 mg/kg i.p | Parasite burdens in the peritoneal cavity and survival rates | Reduction of parasite burden | Effective | – | Tipparaju et al., 2010 |

| 13 | SDS-coated atovaquone | C57BL/6 | ME49 | Acute, chronic | 10 cysts orally | 100 mg/kg | Histology, PCR | Parasite loads and inflammatory changes in brains were significantly reduced | Effective | – | Shubar et al., 2011 |

| 14 | 1NM-PP1 | Old female ICR strain | RH | Acute | 1.0 × 105 tachyzoites i.p | 5 μM orally | Survival rates, parasite load by qPCR | Reduced the parasite load in the brains, livers, lungs | Effective | – | Sugi et al., 2011 |

| 15 | Enrofloxacin | Calomys callosus, C57BL/6 | RH ME49 | Acute, chronic | 100 tachyzoites RH strain 20 cysts per 100/ l (orally) | Subcutaneously for 3 days, 3 mg/kg twice a week for the duration of 25-day | Histological analysis, immunohistochemical assay, survival, cyst counts | diminished significantly the tissue parasitism as well as the inflammatory alterations in the brain | Effective | Sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine | Barbosa et al., 2012 |

| 16 | Small-Molecule (C1, C2, C3, C5) | BALB/c | 5A10, PB3-10 | Acute, chronic | 10,000 tachyzoites i.p | 4.4 mg/kg/day | Survival rates, recording the total number of photons per second from each mouse | C2 showed a significant reduction in parasite load in acute and reduced levels of parasite proliferation and increased survival in chronic phase | C2 effective | – | Kamau et al., 2012 |

| 17 | Endochin-like quinolones (ELQ-271, ELQ-316) | Female CF-1 CBA/J | RH ME49 | Acute, chronic | 20000 tachyzoites (express YFP) i.p 18 cysts of ME49 | 50, 20, 5, 1 mg/kg for 5 day | Counted by flow cytometry | ED50 values of 0.14, 0.08 mg/kg reducing cyst burden by 76–88% | Effective | Atovaquone | Doggett et al., 2012 |

| 5 or 25 mg/kg for 16 day | |||||||||||

| 18 | Spiramycin coadministered with metronidazole | Male BALB/c | ME49 | Chronic | 1000 tachyzoites orally | 400 mg/kg daily for 7 days | Brain cysts counted | Metronidazole increased spiramycin brain penetration, causing a significant reduction of T. gondii brain cysts | Metronidazole alone showed no effect | – | Chew et al., 2012 |

| 500 mg/kg daily | |||||||||||

| 19 | New naphthoquinones, an alkaloid | Female Swiss-Webster | EGS | Chronic | 10 tissue cysts orally | 50 μg/mL of QUI-11, 100 μg/mL of either QUI-6 or QUI-11 | Presence of tachyzoites in the peritoneal cavities and survival rates | The survival rates increased | Effective | Atovaquone | Ferreira et al., 2012 |

| 20 | Prednisolone | Swiss albino | RH ME49 | Acute, chronic | 1 × 104 tachyzoites, iP | 235, 470, 705 mg/kg | Number of tachyzoites present | Greatly improved the number of tachyzoite, cyst forms in mice | No effective | – | Puvanesuaran et al., 2012 |

| 21 | Salicylic acids compounds 14a, 14b | Swiss Webster | RH, RH-YFP, ME49 | Acute | Oocysts orall gavage | 100 or 25 mg/kg orally | Survival rates | Increased survival by 1 day | Effective | Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine | Fomovska et al., 2012 |

| 22 | Atorvastatin | Female Swiss Webster, BALB/c | RH TATi | Acute | 5–20 tachyzoites i.p 10,000–100,000 tachyzoites | 20 mg/kg/day ip | Plaque assays and containing tachyzoites in peritoneal fluid | Atorvastatin protect mice against death, cures a lethal infection | Effective | – | Li et al., 2013 |

| 23 | Fusidic acid | Female BALB/c | Prugniaud | Acute | 5 × 103 or 5 × 104 tachyzoites i.p | 20 mg/kg | Parasite burdens, analyses of host cytokine, and survival rates | There was no statistically significant difference between mice treated with fusidic acid versus saline | No effective | Trimethoprim, sulfadiazine | Payne et al., 2013 |

| 24 | FLZ combined with sulfadiazine, and pyrimethamine | CF1 | RH | Acute | 103 tachyzoites | 10 mg/kg/day of fluconazole with 40/1 mg/kg/day sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine | Survival rates | 93% survival | Effective | Sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine | Martins-Duarte et al., 2013 |

| 25 | Two naphthalene-sulfonyl-indole compounds | BALB/c | RH | Acute | 2 × 106 tachyzoites | 25–800 μmol i.p | Survival rates, liver touch smears with giemsa stained | Both of the compounds was preserved | Effective | Asgari et al., 2013 | |

| 26 | Toltrazuril | lambs | ME49 | Chronic | 1 × 105oocysts | 20, 40 mg/kg orally 2 times, once every week | Presence of tissue cysts by histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and nested-PCR | Cyst presence was determined as 44.4% | Effective | Kul et al., 2013 | |

| 27 | Auranofin | Chicken embryos | RH | Acute | 1 × 104 tachyzoites chorioallantoic vein | 1 mg/kg | Histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and qPCR | Significantly reduced parasite load | Effective | Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine | Andrade et al., 2014 |

| 28 | Spiroindolone | Mice | RH | Acute | 2000 tachyzoites | 100 mg/kg/day | Parasite burdens, measuring the fluorescence intensity | Reduced the parasite burden in mice by 90% | Effective | – | Zhou et al., 2014 |

| 29 | 6-Trifluoromethyl-2-thiouracil KH-0562i and ATT-5126j | ICR female | RH | Acute | 1 × 105 tachyzoites | 100 mg/kg KH-0562i or ATT-5126j orally | Measuring amount of the tachyzoites in mice ascites,LPOk, GSHl, ALTm, ASTn in mouse liver | LPO level-KH-0562 and ATT-5126 = 87.4 and 105.2 nmol/g | KH-0562 more effective | Pyrimethamine | Choi et al., 2014 |

| 30 | Pyrazolopyrimidine-1294 | BALB/c | RH Pru | Acute, chronic | 105 tachyzoites | 100, 30 mg/kg/day for 5 days | Survival rates and number of T. gondii per ml | Decreasing the numbers of T. gondii tachyzoites at both 100, 30 mg/kg | Effective | – | Doggett et al., 2014 |

| 31 | 6-Trifluoromethyl-2-thiouracil KH-0562i, ATT-5126j | Female ICR | RH | Acute | 1 × 105 tachyzoites | 100 mg/kg | Proteomic profiles of T. gondii tachyzoites | Decreased the amount of tachyzoites, mean numbers of tachyzoites = (66.8 ± 0.8) × 106 | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Choi et al., 2014 |

| 32 | Cromolyn sodium, ketotifen | Balb/c | RH | Acute | 4 × 105 tachyzoites | Ketotifen 1, 2 mg/kg, cromolyn sodium 5, 10 mg/kg, ip | Inhibition evaluated under a light microscope with giemsa staining | After 60 min ketotifen at 2 mg/kg (69.83 ± 2.25 %), cromolyn sodium, at 10 mg/kg in (80.47 ± 2/49 %) had the best effect | Effective | – | Rezaei et al., 2014 |

| 33 | Diclazuril plus atovaquone | CD1 mice | PTG Strain | Chronic | 600 tachyzoites-i.p | 65, 120 mg/kg diclazuril | Hematoxylin eosin,Giemsa,immuno histochemical staining | Combination diclazuril plus atovaquone was safe | Effective | – | Oz, 2014b |

| 34 | Diclazuril plus atovaquone | CD1 mice | PTG strain | Chronic | 300, or 600 tachyzoites i.p | 65, 120 mg/kg diclazuril | Hematoxylin and eosin, slides evaluated of colonic tissues | Combined therapy synergistically normalized pathology and to a lesser degree monotherapy | Effective | – | Oz, 2014a |

| 35 | Am80 | BALB/c mice | RH, PLK | Acute | 1 × 10 3 tachyzoites i.p | 1 mg/kg | Survival rates | Percent survival of mice increased statistically | Effective | – | Ihara and Nishikawa, 2014 |

| 36 | Chitosan and silver nanoparticles | Swiss albino | RH | Acute | 3.5 × 103 tachyzoites i.P | 100, 200 μg/ml | Parasite density and ultrastructural parasite changes | Statistically significant decrease in the mean number of the parasite count in the liver and the spleen | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Gaafar et al., 2014 |

| 37 | Pyrimethamine/sulfadiazine | Female C57BL/6 mice | ME49 | Chronic | 20 cysts i.p | Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine 4, 100 mg/kg daily for one month | Histology, qPCR, measured KP metabolites | Significant increases in these kynurenine pathway metabolites were observed in the brain at 28 days post-infection | Effective | – | Notarangelo et al., 2014 |

| 38 | Pyrimethamine-loaded lipid-core nanocapsules | Female CF1 mice | RH | Acute | 103 tachyzoites | 5.0–10 mg/kg/day | Surviving mice, cyst brain evaluation, bioassay urea, AST and ALPo | Survival rate higher than the animals treated with the same doses of non-encapsulated pyrimethamine | Effective | – | Pissinate et al., 2014 |

| 39 | Atovaquone and astragalus combination | BALB/c | RH | Acute | 2 × 104/ml trophozoites | Atovaquone, astragalus 100, 0.075 mg/kg/day oral gavage | Peritoneal trophozoite numbers, IL-2, IL-12, IFN-γp levels were determined by ELISA | The number of trophozoites in the combination groups were found significantly lower than the number of trophozoites in the control group | Effective | – | Sönmez et al., 2014 |

| 40 | Rolipram | Female Swiss albino mice | KSU strain | Chronic | 20 tissue cysts | 10 mg/kg daily for three weeks | Life expectancy, serum Alt, histopathology of liver and brain | Rolipram exerts a significant lowering effect on ALT levels, pathology | Partially effective | – | Afifi et al., 2014 |

| 41 | Rolipram | Female Swiss albino mice | Low pathogenic strain | Chronic | 20 tissue cysts | – | Tissue injury scoring, brain cyst count, specific Ig G titers, TNF- αq, IFN- γ and IL-12 assays | Significant reduction of TNFα (84.6%), IFN- γ (76.7%), IL-12 (71%) | Partially effective | – | Afifi and Al-Rabia, 2015 |

| 42 | Triclosan (TS) and triclosan-loaded liposomal nanoparticles | Swiss strain Albino mice | RH HXGPRT (-) | Acute | 104 tachyzoites | 150 mg/kg TS or 100 mg/kg TS liposomes | Mice mortality, peritoneal, liver parasite burdens | Reduction in mice mortality, parasite burden | Effective | – | El-Zawawy et al., 2015b |

| 43 | Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (ST) associated with resveratrol | Male Swiss albino mice | VEG strain | Chronic | 50 cysts containing bradyzoites | ST (groups B, F), free resveratrol (groups C,G) 0.5, 100 mg kg−1 | Cyst counts in the brain, and histopathology analyses | Combination was able to reduce the number of cysts in the brain, inflammatory infiltrates in the liver, prevented the occurrence of hepatocytes lesions | Effective | Sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim | Bottari et al., 2015 |

| 44 | Ciprofloxacin derivatives (compounds 2, 4,5) | Female Swiss mice | RH | Acute | 5 × 103 tachyzoites i.p | 25, 50, 100, or 200 mg/kg/day a single oral dose | Survival rate, determine the serum levels of urea and creatinine kinase | Increased mouse survival significantly, with 13–25% of mice surviving for up to 60 days post infection | Effective | – | Martins-Duarte et al., 2015 |

| 45 | Triclosan (TS), TS liposomal | Swiss albino mice | ME49 | Chronic | 10 cysts | 200, 120 mg/kg | Mortality,brain parasite burden | TS significant diminution in the parasite burden, great reduction in the infectivity power of T.gondii cysts | Effective | – | El-Zawawy et al., 2015a |

| 46 | 2-(Naphthalene-2-γlthiol)-1H Indole 2-(naphhalene-2-ylthio)-1H-indole | BALB/c | RH | Acute | 2 × 106 tachyzoites exposed to the concentrations of the compound i.p. | 25–800 μM for 1.5 h | Surviving mice, stained by PI and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) | The longevity of mice was dose dependent. Five mice out of group 400 μmol and 3 out of group 800 μmol showed immunization to the parasite | Effective | – | Asgari et al., 2015 |

| 47 | Propranolol | BALB/c | RH | Acute | 1 × 103 tachyzoites i.p | 2, 3 mg/kg/day | Parasite load determined | In the pre-treatment group, propranolol combined with pyrimethamine was more effective | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Montazeri et al., 2015 |

| 48 | Aripiprazole | BALB/c | Tehran strain | Chronic | 50 tissue cysts, i.p | 10, 20 mg/kg | Cysts counted in smears prepared from brain homogenate by optical microscope | No significant difference between mean logarithms of brain cyst numbers of aripiprazole groups compared with control | No effective | – | Saraei et al., 2015 |

| 49 | Pyrimethamine (PYR) and sulphadiazine (SDZ) combined with levamisole and echinacea | BALB/c | RH | 30 days after treatment | 105 tachyzoite i.p | PYR; 6.25, 12.5 SDZ; 100, 200 PYR, SDZ, levamisole; 2.5, echinacea; 130, 260 mg/kg/day oral treatment 24 h later for 10 days | Survival rates | Survival rate PYR+SDZ, and levamisole = 33.3% to 88.9% | Effective | Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine | Köksal et al., 2016 |

| 50 | Miltefosine | Swiss albino mice | RH ME49 | Acute, chronic | 2500 tachyzoites i.p 10 cysts orally | 20 mg/kg for 5 days | Survival rates, tachyzoites count in the liver, spleen, cyst count and size in the brain ultra structural study, and histopathological study | Survival rate in acute = 30% Survival rate in chronic = 5% | No effective in acute. Partially effective in chronic | Sulphadizine | Eissa et al., 2015 |

| 20 mg/kg/day | |||||||||||

| 60 days post infection for 15 days | |||||||||||

| 51 | Tetraoxanes | Female Swiss Webster | RH | Acute | 102 and 106tachyzoite i.p | 10 mg/kg/day, subcutaneously for 8 days | Survival rates and pathohistological analysis | Survival rate = 20 % | Effective | – | Opsenica et al., 2015 |

| 52 | Guanabenz | BALB/c | ME49Prugniaud | Acute, chronic | 104 ME49or 106 Pru tachyzoites, i.p | 5 or 10 mg/kg repeated every 2 days | Survival of mice, qPCR | Enhanced survival, reduces cyst burdens in chronically infected mice | Effective | – | Benmerzouga et al., 2015 |

| 53 | Fluphenazine and Thioridazine | BALB/c | Tehran strain | chronic | 20 tissue cysts i.p | Thioridazine 10, 20, fluphenazine 0.06 mg/kg/ three days after inoculation for 3 weeks | The number of brain cysts | Drugs reduced the percent of cysts at higher dose compared to lower doses | Effective, not significant | Pyrimethamine | Saraei et al., 2016 |

| 54 | Nitrofurantoin | Female ICR mice | RH | Acute | 1 × 105 tachyzoites | 20, 50, and 100 mg/kg, orally once/day for 4 days | The numbers of tachyzoites in the peritoneal cavity, Hematology and biochemical parameters | The inhibition rate = 44.7% hematology indicators and biochemical parameters reduced by nitrofurantoin significantly | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Yeo et al., 2016 |

| 55 | Dextran sulfate | Pigs | RH | Acute | 1 × 106 tachyzoites, intravenously | 50–500 μg per head | host clinical, pathological, and immunological analyses | High-dose caused reversible hepatocellular degeneration of the liver | Effective | . | Kato et al., 2016 |

| 56 | Propranolol | BALB/c | RH | Acute, chronic | 1 × 103 tachyzoites i.p | 2, 3 mg/kg/day | Parasite load determined by qPCR, and survival rate | Decreased the parasite load in brain, eye, and spleen tissues | Effective | Pyrimethamine | Montazeri et al., 2016 |

| 57 | Resveratrol and sulfamethoxazole-trimetropim | Male Swiss Webster | VEG | Chronic | 50 cysts orally | Oral doses of 0.5 and 100 mg/kg/day | Counting brain cysts, tissue oxidant and antioxidant levels, and histopathology | A reduction on the number of cysts in the brain was observed | Co-administration more effective | Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim | Bottari et al., 2016 |

| 58 | Compound 22 of sulfur-containing linear bisphosphonates | Webster mice | RH | Acute | 20 or 100 or 5000 tachyzoites i.p | 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mg/kg of 22/ i.p. for 10 days | Survival rate | ED50= 0.02 mg/kg | Effective | . | Szajnman et al., 2016 |

| 59 | Compound32 (TgCDPK1 inhibitor) | Female CF-1 CBA/J | RH ME49 | Acute, chronic | less than 100 tachyzoites/mL | 20 mg/kg for | The numbers of tachyzoites in spleen, brain/ and the number of brain cysts | Reducing infection in spleen and brain (99%, 95%) 88.7% reduction of brain cyst | Effective | . | Vidadala et al., 2016 |

| 5 days/ oral gavage | |||||||||||

| 30 mg/kg for 14 days |

2-hydroxy-3-(1_-propen-3-phenyl)-1,4-naphthoquinone.

Indirect immunofluorescence antibody test.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Polymerase chain reaction.

Quantitative Polymerase chain reaction.

Fluconazole.

Itraconazole.

1-Hydroxy-2-Alkyl-4(1H) Quinolone.

6-trifluoromethyl-2-thiouracil.

3-[{2-((E)-furan-2-ylmethylene) hydrazinyl} methylene]-1, 3-dihydroindol-2-one.

Lipid peroxidation.

Glutathione-S-transferase.

Alanine aminotransferase.

Aspartate amino transferase.

Alkaline phosphatase.

Interferon gamma.

Tumor necrosis factor.

Cell culture

The cell cultures used in in vitro studies were mostly human foreskin fibroblast (HFF; 39 studies), LLCMK2 (12 studies), Vero (11 studies), Hela (6 studies), mouse macrophage cell line (J774A.1) (5 studies), and MRC-5 (2 studies; Table 3).

Laboratory animals

T. gondii can infect most warm-blooded animals, and is studied in different animal models depending on the nature of the investigation (Szabo and Finney, 2016). The animal model used in studies was mostly mice (16 studies BALB/c and 19 studies Swiss-Webster). In murine models of acute toxoplasmosis, some medicines were protective even when administered at low dosages. But some drugs despite of their excellent in vitro activity were poorly protective in murine models with acute toxoplasmosis (Payne et al., 2013).

Diagnostic tests and evaluation methods

The present review outlines the results of in vitro screening methods including morphological assay, incorporation of [3H] uracil assay, plaque assays, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), colorimetric micro titer assay (b-galactosidase assay), flow cytometric quantification assay, and cell viability assay. Numerous versions of fluorescent proteins have been expressed in T. gondii (Kim et al., 2001). The reporter genes used in vitro and in vivo studies were the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). Parasites expressing fluorescent proteins can also be analyzed and sorted by flow cytometry. This technology used for drugs screening in 10 studies.

Details about the diagnostic methods and drug dosage under in vivo conditions are shown in Table 4. Also, a comprehensive list of drugs/compounds evaluated against T. gondii with regard to IC50 is illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5.

A comprehensive list of drugs/compounds evaluated against T. gondii with regard to IC50.

| Drug | IC50 (μM) | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 1–5 | 5–10 | ||

| Novel quinuclidine | + | Martins-Duarte et al., 2006 | ||

| Novel ferrocenic atovaquone derivatives | Atovaquone (PLK strain) | 2d, 2e, 2f | Baramee et al., 2006 | |

| SAHAa, SBHAb, Scriptaid, Trichostatin A | Scriptaid | Strobl et al., 2007 | ||

| Trichostatin A | ||||

| SAHA | ||||

| SBHA | ||||

| Pyridinylimidazoles SB203580 and SB202190 | RWJ67657, (ME49 strain) | SB202190 | SB203580 | Wei et al., 2007 |

| SB203580 | ||||

| RWJ68198, (ME49 strain) | RWJ68198, (RH strain) | |||

| RWJ67657, (RH strain) | ||||

| 1-hydroxy-2-dodecyl-4(1H) quinolone | + | Saleh et al., 2007 | ||

| Fluorine-containing aryloxyethyl thiocyanate derivatives | Compound 1, 3, 9 | Compound 10 | Liñares et al., 2007 | |

| Novel diamidine analog | + | Leepin et al., 2008 | ||

| Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, atovaquone | + | Meneceur et al., 2008 | ||

| Novel triazine JPC-2067-B | + | Mui et al., 2008 | ||

| 2-alkylaminoethyl-1,1-bisphosphonic acids | Compound 19 | Compound 14, 17 | Szajnman et al., 2008 | |

| Itraconazole | + | Martins-Duarte Edos et al., 2008 | ||

| Thiolactomycin analog | Compound 5, 6 | Compound 2 | Martins-Duarte et al., 2009 | |

| Fluconazole (FLZ) | FLZ (48 h) | FLZ (24 h) | Martins-Duarte et al., 2010 | |

| 1-Hydroxy-2-Alkyl-4(1H) Quinolone derivatives | + | Bajohr et al., 2010 | ||

| Haloperidol, clozapine, fluphenazine, trifluoperazine, thioridazine | + | Goodwin et al., 2011 | ||

| Novel azasterols | Compound 3 (48 h) | Compound 1 (48 h), 2, 3 (24 h) | Compound 1 (24 h) | Martins-Duarte et al., 2011 |

| Endochin-like quinolones | + | Doggett et al., 2012 | ||

| Pterocarpanquinone | + | Portes Jde et al., 2012 | ||

| New naphthoquinones (QUI), an alkaloid | QUI-11 | Ferreira et al., 2012 | ||

| Liriodenine | ||||

| Di-cationic, pentamidine-analog | + | Kropf et al., 2012 | ||

| Fuconazole combined with sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine | Pyrimethamine | + | Martins-Duarte et al., 2013 | |

| Antipsychotic drugs and valproate | Fluphenazine | Zuclopenthixol | Fond et al., 2014 | |

| Thioridazine | ||||

| Fusidic acid | + | Payne et al., 2013 | ||

| Ivermectin and sulphadiazine | Ivermectin | Sulphadiazine | Bilgin et al., 2013 | |

| Novel ruthenium complexes,(compounds 16 and 18) | + | Barna et al., 2013 | ||

| Auranofin | + | Andrade et al., 2014 | ||

| 6-Trifluoromethyl-2-thiouracil | + | Choi et al., 2014 | ||

| 200 drug-like, 200 probe-like compounds of Malaria Box | MMV007791 | MMV007881 | Boyom et al., 2014 | |

| MMV007363 | ||||

| MMV006704 | ||||

| MMV666095 | ||||

| MMV020548 | ||||

| MMV085203 | ||||

| Quinoline derivatives | 8-Hydroxyquinoline, A 11, A14, A18, B11, B12, B15, B23, B24 | A2-6, A12, A15—17, A23, B16, B22, B26, B27, B29, Chloroquine | Quinoline | Kadri et al., 2014 |

| 2-chloroquinoline | ||||

| 5-Nitroqu | ||||

| Inoline Quinoline | ||||

| N-oxide hydrate A7, B18 | ||||

| Bumped Kinase Inhibitor 1294 | + | Doggett et al., 2014 | ||

| Salicylanilides | 3i, 3j, 7a, 14a, 14b | Fomovska et al., 2012 | ||

| Antiretroviral compounds | Atazanavir | Fosamprenavir | Monzote et al., 2013 | |

| Ritonavir | Nelfinavir | |||

| Saquinavir | ||||

| Spiroindolone | + | Zhou et al., 2014 | ||

| Ciprofloxacin derivatives | Compound 2, 5 | Compound 4 | Dubar et al., 2011 | |

| Thiazolidin-4-one derivatives | 12A | 27, 34 A | 36 A | D'Ascenzio et al., 2014 |

| N6-benzyladenosine analog | Compound 11 e, g, j, n, o, q, u, v | Kim et al., 2007 | ||

| Naphthoquinone derivative | LQB151 (48 h) | LQB94 | da Silva et al., 2015 | |

| LQB151 (24 h) | ||||

| LQB150 (24, 48 h) | ||||

| Oryzalin analogs | Compound 6a, h, i, 14a, 18a, b, c | Compound 6b, g, j, I, n, 12 | Compound 6m, 14b | Endeshaw et al., 2010 |

| 94 compounds | + | Dittmar et al., 2016 | ||

| 6-(1,2,6,7-tetraoxaspiro[7.11] nonadec-4-yl)hexan-1-ol (N-251) | + | Xin et al., 2016 | ||

Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid.

Suberic bishydroxamic acid.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the in vitro and in vivo effects of anti-Toxoplasma drugs and synthetic compounds, from 2006 to 2016. The current anti-T. gondii chemotherapy is deficient; as it is not well-tolerated by immunocompromised patients and cannot completely eradicate tissue cysts produced by the parasite (Rodriguez and Szajnman, 2012). Therefore, developing new, safe, effective, and well-tolerated drugs with novel mechanisms of action could be a global priority (Lai et al., 2012). An ideal drug for prophylaxis and/or treatment of toxoplasmosis would show effective penetration and concentration in the placenta, transplacental passage, parasiticidal properties vs. the different parasitic stages, penetration into cysts, and distribution in the main sites. No available drug fulfills these criteria (Derouin et al., 2000; Montoya and Liesenfeld, 2004).

Thus, the findings of the present systematic review article encourage and support more accurate investigations for future to select new anti-Toxoplasma drugs and strategies in designing new targets with specific activity against the parasite.

Activities of anti-toxoplasma clinically available drugs

With growing parasite resistance to therapeutic drugs and in the absence of a vaccine, to increase the effectiveness of drugs, various changes have been made in construction of the clinically available medicines. Thus, the activity of new formulations of clinically available drugs against T. gondii should be evaluated to find alternative treatments for toxoplasmosis (da Cunha et al., 2010).

Interestingly, encapsulation of pyrimethamine improved the efficacy and tolerability of this drug against acute toxoplasmosis in mice and can be considered as an alternative for reducing the dose and side effects of pyrimethamine (Pissinate et al., 2014). Recently, researchers reported that computational analysis of biochemical differences between human and T. gondii dihydrofolate reductase enabled the design of inhibitors with both improved potency and selectivity against T. gondii (Welsch et al., 2016). El-Zawawy et al. reported that incorporating triclosan into in the lipid bilayer of liposomes allowed its use in lower doses, which in turn, reduced its biochemical adverse effects (El-Zawawy et al., 2015b). In another study, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-coated atovaquone nanosuspensions (ANSs) considerably increased the therapeutic efficacy against experimentally reactivated and acquired toxoplasmosis by improving passage of gastrointestinal and blood-brain barriers. Accordingly, coating of ANSs with SDS may improve the treatment of toxoplasmic encephalitis and other cerebral diseases (Shubar et al., 2011).

Also, various studies showed that a number of drugs were investigated for the mechanisms of action summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2. One study discussing the metabolic differences between the host and the parasite noted that dihydrofolate reductase, isoprenoid pathway, and T. gondii histone deacetylase are promising molecular targets (Rodriguez and Szajnman, 2012).

Novel triazine JPC-2067-B (4, 6-diamino-1, 2-dihydro-2, 2-dimethyl-1-(3′(2-chloro-, 4-trifluoromethoxyphenoxy)propyloxy)-1, 3, 5-triazine), the anti-folate medicines, is highly effective against T. gondii with an IC50 of 0.02 μM, which is more efficacious than pyrimethamine and has in vitro cidal activity. Additionally, pro-drug JPC-2056 (1-(3′-(2-chloro-4-trifluoromethoxyphenyloxy) propyl oxy)-5-isopropylbiguanide) is effective in vivo when administered orally (Mui et al., 2008). Moreover, histone deacetylase is potentially a very important drug target in T. gondii, since scriptaid and trichostatin A had the highest effect against T. gondii tachyzoite proliferation with the IC50 of 0.039 and 0.041 μM, respectively (Strobl et al., 2007). For promising anti- T. gondii drugs/compounds, assessment of their ability to control parasite growth is a key step in drug development (McFarland et al., 2016).

A large number of research papers suggested that the apicoplast represents a potential drug target for new chemotherapy, as it is essential to the parasite and it is absent in host cells. Functions of the apicoplast include fatty acid synthesis, protein synthesis, DNA replication, electron transport, and heme biosynthesis (Yung and Lang-Unnasch, 2004). Some of the drugs evaluated against T. gondii are shown to act in the apicoplast such as thiolactomycin, triclosan (TS), azithromycin, fusidic acid, ciprofloxacin, and quinoline derivatives (Costa et al., 2009; Martins-Duarte et al., 2009, 2015; Payne et al., 2013; Kadri et al., 2014; El-Zawawy et al., 2015b).

In T. gondii, FAS-II enzymes are present in the apicoplast and are essential for its survival. The key enzyme in this process is the ENR enzyme, which is not found in mammals (Surolia and Surolia, 2001). This enzyme catalyzes the last reductive step of the type II FAS pathway. The TS, which inhibits type II FAS, significantly reduced mice mortality, parasite burden, as well as viability and infectivity of tachyzoites and cysts harvested from infected treated mice and their brains. Accordingly, TS is proved as an effective, promising, and safe preventive drug against acute and chronic murine toxoplasmosis. Liposomal formulation of TS enhanced its efficacy and allowed its use at a lower dose (Surolia and Surolia, 2001; El-Zawawy et al., 2015a,b). Among apicoplast pathways, DNA replication is an important potential chemotherapeutic target. Fluoroquinolones are the known DNA replication inhibitors that target prokaryotic type II topoisomerases (Collin et al., 2011). In two studies, researchers showed that derivatives of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone, are active against T. gondii tachyzoites both in vitro and in vivo (Neville et al., 2015). While all mice treated with ciprofloxacin died by day 10 post-infection, some mice treated with ciprofloxacin derivatives remained alive for at least 60 days, suggesting that ciprofloxacin derivatives cured T. gondii infection in treated mice (Dubar et al., 2011; Martins-Duarte et al., 2015).

Anti-toxoplasma activities of new synthetic compounds

There are numerous reports on efficacy of many new synthetic compounds with a focus on identifying drug candidates with innovative and acceptable profiles against T. gondii. The anti-coccidial effect of 1-[4-(4-nitrophenoxy) phenyl] propane-1-one (NPPP), a synthetic compound, was studied both in vitro and in vivo. Treatment with NPPP showed anti-Toxoplasma activity in vitro with a lower EC50 value than pyrimethamine. In ICR mice infected with T. gondii, oral administration of NPPP for 4 days showed statistically significant anti-Toxoplasma activity with lower number of tachyzoites than those of the negative control (Choi et al., 2015).

In a study by Kadri et al. anti-Toxoplasma properties of 58 newly synthesized quinoline compounds were evaluated. A significant improvement in anti-Toxoplasma effect among quinoline derivatives was detected in B11, B12, B23, and B24. Among these compounds, B23 was the most effective compound with the IC50 value of < 1 μM, displaying its anti-Toxoplasma effects and ability to cause the disappearance of the apicoplast (40–45% of the parasites lost their apicoplasts; Kadri et al., 2014).

In a study by Boyom et al. the strategy adopted was to repurpose the open access Malaria Box to identify chemical series active against T. gondii. The results showed that the most interesting compound was MMV007791, a piperazine acetamide, which has an IC50 of 0.19 μM. This compound is novel for its anti-Toxoplasma activity, and of course, further studies on the rates and mechanisms of compound action will elucidate these considerations (Boyom et al., 2014).

Tetraoxanes, anti-cancer molecules, were tested in vivo against T. gondii. Subcutaneous, administration of a 10 mg/kg/day dose of derivative 21, for 8 days allowed the survival of 20% of infected mice, demonstrating the high potential of tetraoxanes for the treatment of T. gondii (Opsenica et al., 2015).

In another study by Moine et al. researchers evaluated in vitro anti-T. gondii activity of 51 compounds with a biphenylimidazoazine scaffold. Eight of these compounds displayed highly potent activity against T. gondii growth in vitro, with 50% effective concentration (EC50) below 1 mM, without demonstrating cytotoxic effects on human fibroblastic cell at equivalent concentrations. However, these compounds have to be evaluated in animal models so as to confirm their in vivo activity (Moine et al., 2015a).

Several pathways were characterized and shown to differ significantly from those of the mammalian host cells, thus, revealing an attractive area for therapeutic intervention. 1-Hydroxy-2-Alkyl-4 (1H) quinolone derivatives inhibit the fourth step of the essential de novo synthesis of pyrimidine, which uses ubiquinol reduction as an electron sink for dihydroorotate oxidation (Saleh et al., 2007). Also, newly synthesized bisphosphonates interfere with the mevanolate pathway, which leads to the synthesis of sterols and polyisoprenoid compounds that are important for parasite survival (Shubar et al., 2008).

Interestingly, Kamau et al. identified novel kinases that are integral to essential pathways, elucidating their mechanism of action and ultimately, identifying new drug targets (Kamau et al., 2012). In that study, 527 compounds were evaluated in vitro; also, they assessed the impact of the inhibitory compounds C1, C2, C3, and C5 in mouse models of toxoplasmosis. C2 was found quite effective in decreasing the parasite burden and increasing mice survival. These results should be considered with caution, since there are a number of factors are at play in whether a compound will be in vivo effective, such as solubility in vivo, access to different tissues, and host metabolic processes (Kamau et al., 2012). In a recent study, Dittmar et al. screened a collection of 1,120 compounds, 94 of which were blocked parasite replications with IC50 of <5 μM. These data suggest that tamoxifen restricts Toxoplasma growth by inducing xenophagy or autophagic destruction of this parasite (Dittmar et al., 2016). According to a new study, in silico screening is useful, particularly in the identification of molecular targets in the laboratory. Fernandez et al. synthesized VAM2 compounds (7-nitroquinoxalin-2-ones), based on the design obtained from an in silico prediction with the software TOMOCOMD-CARDD. From the group of VAM2 compounds, Fernandez et al. chose VAM2-2 with an IC50 of 3.3 μM against T. gondii. However, more studies are required to evaluate its effect on the cysts formed by of the parasite and in animal models of toxoplasmosis (Fernández et al., 2016).

Activity of drugs, compounds, and combined therapy against cysts