Abstract

Proteomes of even well characterized organisms still contain a high percentage of proteins with unknown or uncertain molecular and/or biological function. A significant fraction of those proteins is predicted to have catalytic properties. Here we aimed at identifying the function of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ydr109c protein and its human homolog FGGY, both of which belong to the broadly conserved FGGY family of carbohydrate kinases. Functionally identified members of this family phosphorylate 3- to 7-carbon sugars or sugar derivatives, but the endogenous substrate of S. cerevisiae Ydr109c and human FGGY has remained unknown. Untargeted metabolomics analysis of an S. cerevisiae deletion mutant of YDR109C revealed ribulose as one of the metabolites with the most significantly changed intracellular concentration as compared with a wild-type strain. In human HEK293 cells, ribulose could only be detected when ribitol was added to the cultivation medium, and under this condition, FGGY silencing led to ribulose accumulation. Biochemical characterization of the recombinant purified Ydr109c and FGGY proteins showed a clear substrate preference of both kinases for d-ribulose over a range of other sugars and sugar derivatives tested, including l-ribulose. Detailed sequence and structural analyses of Ydr109c and FGGY as well as homologs thereof furthermore allowed the definition of a 5-residue d-ribulokinase signature motif (TCSLV). The physiological role of the herein identified eukaryotic d-ribulokinase remains unclear, but we speculate that S. cerevisiae Ydr109c and human FGGY could act as metabolite repair enzymes, serving to re-phosphorylate free d-ribulose generated by promiscuous phosphatases from d-ribulose 5-phosphate. In human cells, FGGY can additionally participate in ribitol metabolism.

Keywords: carbohydrate metabolism, enzyme kinetics, mass spectrometry (MS), metabolomics, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), protein motif, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, structural model, FGGY carbohydrate kinase family, ribulose

Introduction

A major challenge in the post-genomic era is that a large fraction of protein-coding genes remain functionally unknown or poorly characterized in all sequenced genomes (1, 2). Even in a well characterized organism such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the number of protein-coding genes with no known biological function, based on database searches in UniProt, amounts to ∼30%, which corresponds to about 2000 proteins. In this study, we investigated the function of two proteins of unknown function, the S. cerevisiae Ydr109c protein (Q04585) and its human homolog FGGY (Q96C11). Both proteins contain the highly conserved FGGY_N and FGGY_C Pfam domains. The members of the FGGY family of carbohydrate kinases, of which more than 8000 sequences are known according to the Pfam database, are widespread across the various kingdoms of life and show a high functional diversification (3). They phosphorylate C3 to C7 sugars or sugar derivatives, and a divergent subfamily of the FGGY protein family is involved in quorum sensing by phosphorylating the signaling molecule autoinducer-2 (AI-2, a furanosyl borate diester) (3). There are seven Swiss-Prot-reviewed FGGY domain-containing proteins encoded by the human genome as follows: sedoheptulokinase (Q9UHJ6); xylulose kinase (O75191); glycerol kinase (P32189); glycerol kinase 2 (Q14410); putative glycerol kinase 3 (Q14409); putative glycerol kinase 5 (Q6ZS86); and FGGY carbohydrate kinase domain-containing protein (Q96C11; designated hereafter as “FGGY”). The S. cerevisiae genome encodes four Swiss-Prot-reviewed FGGY domain-containing proteins: xylulose kinase (P42826); glycerol kinase (P32190); Mpa43 (P53583); and Ydr109c (Q04585). The motivation behind this study was the existence of a functionally uncharacterized carbohydrate kinase (Ydr109c) in S. cerevisiae with a homologous protein in humans (FGGY), which has been linked to S-ALS2 and bipolar disorder.

The first study reporting an FGGY association to S-ALS was by Dunckley et al. (4). Performing a genome-wide association study comparing healthy controls and S-ALS patients of European Caucasian descent living in the United States, the authors reported 10 statistically significant single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with S-ALS. The most significant gene associated with S-ALS was FGGY (FLJ10986). Assessment of FGGY expression in the same study using Western blotting indicated the presence of FGGY protein in cerebrospinal fluid, spinal cord, small intestine, lung, kidney, liver, and fetal brain. Association of the FGGY gene with S-ALS could, however, not be confirmed in subsequent studies using different cohorts (5–9). The contradictory results on the involvement of FGGY in S-ALS were suggested to be due to the variable causes and complexity of the disease itself (10). An exome sequencing study, which was carried out in a family with three female patients affected by bipolar disorder and one unaffected male sibling, identified heterozygous, very rare, and likely protein-damaging variants in eight brain-expressed genes, including FGGY (11). These variants were shared by the three affected siblings but were not present in the unaffected sibling and in more than 200 controls. Replication and functional studies would, however, be required to confirm disease association and test causality, respectively, of the identified variants. Although these observations suggest a possible link of the FGGY gene with neurodegenerative or psychiatric disorders, the overall evidence supporting this link thus remains limited at this stage.

In recent years, metabolomics has emerged as a new tool for discovery of enzyme function. Untargeted metabolomics has enabled us to analyze metabolites in biological samples in a much more comprehensive way and is a powerful technique for hypothesis generation. A remaining challenge of this methodology is metabolite identification; the data obtained via untargeted metabolomics contains thousands of metabolite features, with relatively few being identified in the end (12). In contrast to untargeted metabolomics, targeted metabolomics serves to identify and/or quantify a more or less limited set of preselected metabolites. In the field of enzymology, metabolomics or metabolite profiling techniques may be exploited to identify endogenous enzyme substrates. Ewald et al. (13) studied the effect of single enzymatic gene deletions in central carbon metabolism and of environmental changes on the metabolome of S. cerevisiae. 30–40% of the enzymatic gene deletions tested led to a very local metabolic response in proximity of the enzyme deficiency (often accumulation of the substrate of the deleted enzyme) (13). The observations suggest that this approach is a viable strategy for enzyme function identifications through comparative metabolomics analyses of wild-type cells and cells deficient in metabolic enzymes of unknown function. A notable advantage of this type of approach over in vitro substrate screens with purified enzymes is the higher likelihood of identifying the true physiological or endogenous substrate(s) of the deleted enzyme under investigation (14). Two recent examples of enzyme identifications in connection with the pentose phosphate pathway and using LC-MS-based metabolite profiling in samples derived from enzyme-deficient organisms are yeast sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphatase (SHB17) (15) and mammalian sedoheptulokinase (SHPK) (16).

LC-MS-based metabolite profiling can involve full scan or tandem MS methods. In the full scan MS methods, only the m/z of parent ions and/or adducts of the parent ions are utilized along with the retention time characteristic of each molecule to identify detected metabolites. Tandem MS methods increase the potential for metabolite identification by allowing the generation of m/z fingerprints (MS2 spectra), obtained by fragmenting the parent ions, that can then be matched with those of metabolite standards. We used a combination of untargeted full scan MS, ddMS2, and targeted methods to search for the endogenous substrate of the S. cerevisiae Ydr109c protein using ydr109cΔ knock-out strains. We found that ribulose was one of the most significantly changed metabolites, accumulating in the ydr109cΔ mutants as compared with the wild-type control strains. d-Ribulose was subsequently shown to be the preferred substrate of the yeast Ydr109c kinase as well as for its human homolog FGGY in vitro. In contrast to yeast cells, ribulose formation in human HEK293 cells could only be detected when ribitol was supplemented to the cultivation medium. Under this condition, FGGY knockdown led to ribulose accumulation in the HEK293 cells. Taken together, our results establish the molecular identity of d-ribulokinase in yeast and humans. Furthermore, combined sequence and structural analyses allowed us to identify a conserved signature motif that enables the prediction of d-ribulokinase activity with high confidence for FGGY protein family members.

Results

YDR109C Gene Deletion Leads to Ribulose Accumulation in Different S. cerevisiae Strains

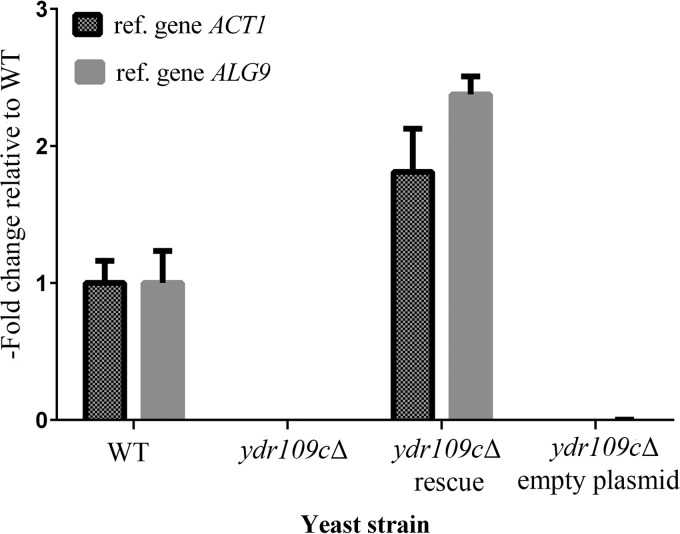

The YDR109C gene is currently annotated as an uncharacterized open reading frame in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD), which means, according to the SGD glossary, that “there are no specific experimental data demonstrating that a gene product is produced in S. cerevisiae.” In addition, no molecular or biological function has been assigned to this gene yet. Therefore, we started by investigating YDR109C expression in our prototrophic WT strain by quantitative RT-PCR. The YDR109C transcript was readily detected in exponentially growing wild-type cells (Fig. 1), with an average measured cycle threshold (Ct) value of 26.3 ± 0.3 (mean ± S.D.; n = 3) as compared with an average measured Ct value of 23.8 ± 0.5 (mean ± S.D.; n = 3) for the mannosyltransferase ALG9, which is commonly used as a reference gene for quantitative RT-PCR studies in S. cerevisiae (17). The YDR109C transcript was not detectable in our ydr109cΔ prototrophic knock-out strain (Fig. 1). These results show that YDR109C is transcribed in S. cerevisiae and indicate that our knock-out strain is a good model to explore the function of this gene. The Ydr109c protein was also detected and quantified (119 molecules/cell) in a proteomics study (18).

FIGURE 1.

Expression levels of the YDR109C gene in the prototrophic yeast strains used in this study. Total RNA was extracted from exponentially growing cells of the WT and ydr109cΔ strains as well as the ydr109cΔ strain transformed with the p41Hyg 1-F::YDR109C plasmid (rescue) or the corresponding empty plasmid. The expression fold change of the YDR109C gene in the indicated strains relative to the WT strain was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The expression level of the YDR109C gene in each sample was either normalized to reference gene ACT1 or ALG9. Means and standard deviations of three biological replicates are shown.

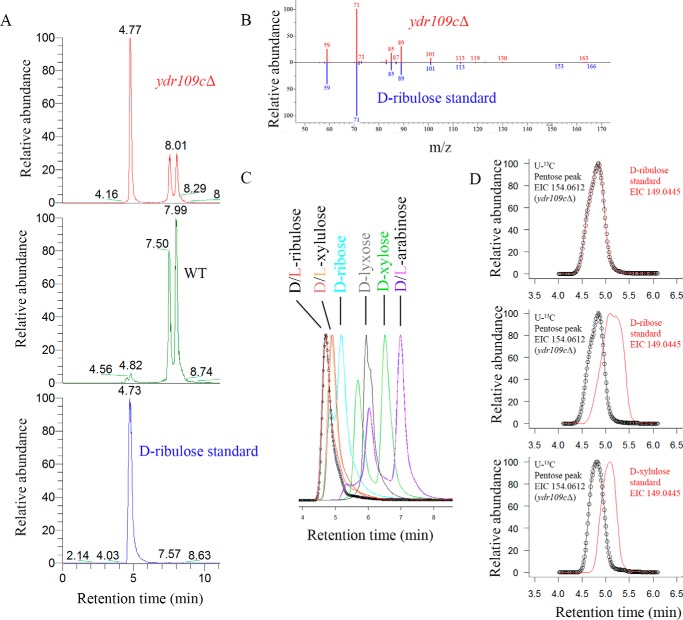

The Ydr109c protein sequence contains the widely conserved Pfam FGGY_N and FGGY_C domains, suggesting that it functions, as other members of the FGGY protein superfamily, as a kinase acting on sugars or sugar derivatives. To identify endogenous substrate candidates of this putative sugar kinase, we analyzed the polar metabolites extracted from our prototrophic WT and ydr109cΔ strains using LC-HRMS. Two complementary methods, ZIC-HILIC coupled to ddMS2 and reverse phase chromatography coupled to full scan MS with polarity switching, were used. Ribulose was found to be the metabolite with the highest fold change (more than 30-fold increase in KO versus WT), among the ones confirmed to be produced endogenously by the co-cultivation method described below, using the ZIC-HILIC-ddMS2 method in negative ionization mode (Fig. 2A and supplemental Table S1). We repeated the same analysis in metabolite extracts derived from a ydr109cΔ deletion strain in the auxotrophic background BY4741 and the corresponding WT strain. As for the prototrophic strains, ribulose was identified as the most significantly changed metabolite, accumulating in the auxotrophic ydr109cΔ mutant, among the metabolites detected in negative mode (23-fold increase in KO versus WT; supplemental Table S2). Identification of the accumulating compound as ribulose was based on accurate mass (m/z 149.0445), co-elution with a d-ribulose standard (Fig. 2A), and MS2 fragmentation pattern (Fig. 2B). Polar metabolites were separated better using ZIC-HILIC; the bulk of yeast polar metabolites eluted very early with our reverse phase chromatography method and was therefore not used for further experiments in this study. Using the ZIC-HILIC-based method, we were able to separate ribulose from other pentoses (Fig. 2C). We were, however, not able to separate the d- and l-forms of ribulose. Although we could detect a number of other sugars and sugar derivatives, including glucose, arabinose, mannitol, ribitol, maltose, xylose, galactose, and 2-deoxyribose (identification based on accurate mass and co-elution with standards) in the analyzed yeast metabolite extracts, only ribitol showed significantly different levels (>2-fold higher in the prototrophic and auxotrophic KO strains than in the corresponding WT strains; supplemental Tables S1–S4) upon YDR109C deletion in addition to ribulose. Taken together, these analyses highlighted ribulose as a strong endogenous substrate candidate for the putative Ydr109c kinase.

FIGURE 2.

Ribulose accumulates in an S. cerevisiae ydr109cΔ strain. A, extracted ion chromatograms (m/z 149.0445) obtained after ZIC-HILIC-MS analysis of ydr109cΔ and wild-type metabolite extracts as well as a d-ribulose analytical standard. B, head-to-tail comparison of the MS2 fragmentation pattern of the parent ion m/z 149.0445 detected in the ydr109cΔ extract at retention time of 4.77 min and the d-ribulose standard. C, extracted ion chromatograms (m/z 149.0445) of pentose and pentulose analytical standards analyzed by ZIC-HILIC-MS. The d- and l-forms of the sugars were not separable using ZIC-HILIC chromatography; all other isomers were separable at peak maxima. D, overlay of extracted ion chromatograms (m/z 149.0445 in red and m/z 154.0612 in black) obtained after ZIC-HILIC-MS analysis of a ydr109cΔ metabolite extract generated from cells cultivated in the presence of d-[U-13C]glucose as the sole carbon source and supplemented with non-labeled d-ribulose, d-ribose, or d-xylulose standards.

Free ribulose has not been described so far as an endogenous metabolite in S. cerevisiae, and there is also no entry for ribulose in the YMDB (19). Our detection of ribulose accumulation in yeast strains grown on controlled minimal medium containing d-glucose as the sole carbon source suggested that yeast cells can form free ribulose from d-glucose. We wanted to consolidate this observation via stable isotope labeling (SIL) experiments in which we replaced the non-labeled glucose with d-[U-13C]glucose in an otherwise identical cultivation medium. In these experiments, we observed a +5 m/z shift for the pentose peak (monoisotopic mass of 154.0612) accumulating in the ydr109cΔ mutant and perfectly co-eluting with a supplemented d-[12C]ribulose standard (Fig. 2D). As can also be seen in Fig. 2D, supplemented non-labeled d-xylulose and d-ribose standards, which elute in close proximity to the d-ribulose standard (see Fig. 2C), eluted slightly later than the labeled pentose accumulating in the ydr109cΔ mutant. These results consolidate the identity of the compound building up after deletion of the YDR109C gene as ribulose and show that S. cerevisiae can produce this compound from d-glucose. Using a 13C internal standard isotope dilution MS method and biovolume measurement by Coulter counter, we estimated an intracellular ribulose concentration of 0.054 ± 0.010 and 2.2 ± 0.3 mm (means ± S.D.; n = 6) for the prototrophic WT and ydr109cΔ strains, respectively.

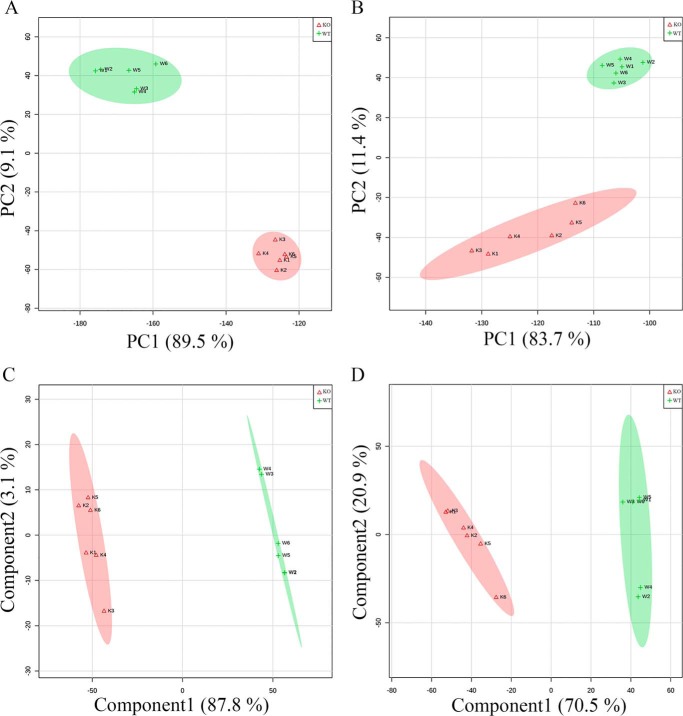

Effect of YDR109C Deletion on Metabolite Levels Other than Ribulose and Ribitol

The ZIC-HILIC-ddMS2 data obtained with the prototrophic strains were further analyzed to investigate whether the levels of additional metabolites were significantly affected in response to YDR109C gene deletion. Principal component analysis (PCA) of the mTIC-normalized negative and positive mode data produced clusters separating WT and ydr109cΔ samples in a PC1 versus PC2 plot in which all the replicates were within the 95% CI of their group centroids (Fig. 3, A and B). Because PCA is an unsupervised visualization method, which is not guaranteed to preserve well the distances between the original untransformed data points, the partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) supervised method was additionally used to investigate the separability between the sample groups and to find features important in differentiating the WT from the ydr109cΔ strain. The data showed clear separation of the WT and ydr109cΔ replicate groups using PLS-DA as well, with again all the replicates lying within the 95% CI of their respective group (Fig. 3, C and D). The supplemental Tables S1–S4 contain a column with variable importance in projection scores for all the listed m/z features, reflecting their importance for PLS-DA separation of the WT and ydr109cΔ samples.

FIGURE 3.

Multivariate statistics analyses of the metabolite profiles obtained for the wild-type and ydr109cΔ prototrophic stains using ZIC-HILIC-MS. In the score plots shown, the green and red oval shapes represent the 95% confidence intervals for the wild-type (WT; green + symbols) and ydr109cΔ (KO; red Δ symbols) replicates, respectively. A, PCA score plot showing principal component 1 (PC1) versus PC2 for the negative mode mTIC normalized data. B, PCA score plot for the positive mode mTIC normalized data. C, PLS-DA score plot showing component 1 versus component 2 for the negative mode mTIC normalized data. Leave-one-out cross-validation statistics were R2 = 0.99 and Q2 = 0.98 for component 1, and R2 = 1.00 and Q2 = 0.99 for component 2. D, PLS-DA score plot for the positive mode mTIC normalized data. Leave-one-out cross-validation statistics were R2 = 0.98 and Q2 = 0.96 for component 1 and R2 = 0.99 and Q2 = 0.96 for component 2. mTIC, metabolic total ion chromatogram.

Fold changes between the prototrophic WT and ydr109cΔ strains for each metabolite feature detected by ZIC-HILIC-ddMS2 and associated p values were calculated using Welch's t test for unequal variances. Unexpectedly, the levels of as many as 92 and 213 non-redundant metabolite features having m/z matches in the KEGG database were found to be changed at least 2-fold and with a p value lower than 0.05 between the two strains in the negative and positive ionization modes, respectively. These numbers dropped to 26 and 69 non-redundant metabolite features, respectively, when only features with additional m/z matches in the YMDB (19) were retained (supplemental Tables S1 and S3). Interestingly, several intermediates of the arginine synthesis pathway (N-acetylglutamate, ornithine, N-acetylornithine, and N-acetylglutamate semialdehyde; supplemental Table S3) as well as several intermediates or derivatives of the kynurenine pathway for tryptophan catabolism (tryptophan itself, formylkynurenine, kynurenine, 3-hydroxykynurenine, 3-hydroxyanthranilate, kynurenic acid, and xanthurenic acid) ranged among the most significantly changed metabolites, and accordingly, some of those metabolites also had the highest scores in the PLS-DA. Given that those two pathways do not share any obvious connection with ribulose metabolism, we wanted to test whether similar changes could also be found upon YDR109C deletion in a different genetic background. We therefore also analyzed the ZIC-HILIC-ddMS2 data obtained for the auxotrophic WT and ydr109cΔ strains using multivariate and univariate statistics. In strong contrast to the prototrophic strains, the auxotrophic WT and ydr109cΔ strains showed much more similar metabolite profiles, and corresponding samples did not form two separate clusters after PCA of the non-targeted metabolomics data obtained in negative or positive ionization mode (data not shown). Data analysis using the Welch's t test yielded nevertheless 8 and 21 significantly changed metabolite features (2 and 11 metabolite features when retaining only features with matches in both the KEGG and YMDB databases; supplemental Tables S2 and S4) in the auxotrophic ydr109cΔ strain compared with the WT strain in the negative and positive ionization mode, respectively. Comparing those changes to the ones observed for the prototrophic strains, only two metabolites differed significantly between WT and KO in both genetic backgrounds in the negative mode (ribulose and ribitol), and nine metabolites were changed significantly in the KO versus the WT strain in both genetic backgrounds in the positive mode (all metabolites listed in supplemental Table S4, except for 4-aminobutanoate and methionine sulfoxide). As described above, this showed that the ribulose and ribitol accumulations observed upon YDR109C deletion are robust changes likely to be specifically linked to this gene, whereas the metabolite changes observed in the arginine synthesis and tryptophan degradation pathways upon YDR109C deletion in the prototrophic strain are background-specific.

To further test which of the KO versus WT metabolite changes in the prototrophic background were specifically caused by YDR109C deficiency, we generated a rescue strain (KOres or ydr109cΔ rescue) expressing YDR109C under the control of the endogenous promoter from a low copy number plasmid conferring resistance to hygromycin B (p41Hyg 1-F) in the ydr109cΔ background. Using quantitative RT-PCR, we measured two times higher YDR109C transcript levels in the rescue strain than in the corresponding wild-type strain (Fig. 1), validating the rescue strategy at the gene expression level. The YDR109C transcript was not detectable in a ydr109cΔ strain transformed with an empty plasmid (KOcnt or ydr109cΔ empty plasmid; Fig. 1). Polar metabolites extracted from the KOcnt and KOres strains were analyzed using ZIC-HILIC-ddMS2 in positive and negative ionization mode. Although ribulose levels were consistently lower in the rescue strain than in the empty vector control strain (KOcnt/KOres ratio of 1.7 with a p value of 0.0000005 calculated using the unequal variances Welch's t test; n = 6), the rescue efficiency was only very partial at the metabolite level given the more than 30-fold higher levels of ribulose measured in the non-transformed ydr109cΔ strain compared with the prototrophic wild-type control strain (supplemental Table S1). Except for N-acetylglutamate, N-acetylglutamate 5-semialdehyde, ribitol, and deoxyribose, other metabolite changes observed in the prototrophic ydr109cΔ strain compared with the wild type were either not found or were found to vary in opposite direction in the KOcnt versus KOres strain comparison (data not shown). Such results typically would suggest that those supplementary changes in the metabolite profiles of the original strains were due to the presence of secondary mutations present in the ydr109cΔ mutant but not in the wild-type control strain. However, given the incomplete rescue of the ribulose metabolic phenotype, it seems that the rescue plasmid used led, for reasons that remain unclear, to the formation of a transcript that does not allow reconstitution of wild-type protein and/or wild-type enzyme activity levels, potentially explaining why other metabolic changes were not rescued.

We next adapted a recently published SIL workflow (20) for improved untargeted metabolomics data analysis to our experimental model. Our prototrophic wild-type and ydr109cΔ strains were cultivated in parallel in controlled minimal medium supplemented either with non-labeled d-glucose or with d-[U-13C]glucose as the sole carbon source (both the non-labeled and the fully labeled glucose were added at a final concentration of 2% (w/v)). Polar metabolites were extracted from the four cultivations, and the 13C-labeled extracts derived from both the wild type and the ydr109cΔ cells were pooled. This labeled pooled sample was added as an internal standard into the individual non-labeled metabolite extracts of the wild-type and ydr109cΔ strains, and the supplemented samples were analyzed by ZIC-HILIC-ddMS2 in positive or negative ionization mode. Data analysis was performed using an extended version of the MetExtract software (20, 21). The data filtering based on SIL-specific isotopic patterns and subsequent grouping of 12C and 13C feature pairs greatly enriches the processed mass spectrometry dataset in small molecules that are produced intracellularly and assists with metabolite identification by the number of carbon atoms that can be deduced for each metabolite from the difference in mass between the 13C and 12C ions. Using this strategy, we again confirmed that ribulose (as well as ribitol) is produced endogenously by S. cerevisiae cells from d-glucose, but we also could extend this conclusion to all the other detected metabolite features that had a matching U-13C counterpart, and we could use this information to improve metabolite identification in our untargeted metabolomics dataset, with a focus on the metabolites that were found up- or down-regulated in the ydr109cΔ strain (supplemental Tables S1 and S3). This added an additional level of confidence to identifications for metabolites that were not represented in our in-house metabolite library (and conversely also allowed questioning of metabolite identifications based on accurate mass matches in the KEGG and YMDB databases; see, for example, the most significantly changed metabolite, detected in the positive mode, identified as N-acetyl-l-glutamate-5-semialdehyde by the KEGG and YMDB accurate mass match, but for which the co-cultivation method revealed a carbon number that does not concur with this identification). Notably, the identities of some of the arginine synthesis pathway intermediates (N-acetylglutamate and ornithine) as well as of the kynurenine pathway intermediates or derivatives (tryptophan, formylkynurenine, kynurenine, 3-hydroxykynurenine, 3-hydroxyanthranilate, kynurenic acid, and xanthurenic acid) that were found to significantly change between the prototrophic WT and ydr109cΔ strains were in this way further consolidated (supplemental Tables S1 and S3).

Deficiency of Another FGGY Protein Family Member Encoded by the S. cerevisiae Genome, Mpa43, Does Not Lead to Pentose Accumulation

BLAST searches revealed that the S. cerevisiae genome encodes a protein (Mpa43) that is highly similar to the Ydr109c protein. Mpa43 is a smaller protein (542 amino acids) than Ydr109c (715 amino acids), and the N- and C-terminal sequences of the two proteins do not share sequence similarity. However, about 70% of the Ydr109c protein sequence (from amino acids 41–552) aligns well with Mpa43, showing 28% sequence identity. Mpa43 also contains the conserved FGGY_N and FGGY_C domains. While nothing is known on the subcellular localization of Ydr109c, the Mpa43 protein was detected in highly purified mitochondria in high throughput studies (22, 23). This is in disagreement with scores obtained with the TargetP program (24), which predicted Mpa43 to be neither mitochondrial nor targeted to the secretory pathway, although for Ydr109c it computed the highest score for a mitochondrial localization (with, however, a low reliability). Given the protein sequence similarities between Ydr109c and Mpa43, we also analyzed metabolite extracts derived from a prototrophic strain knocked out for the MPA43 gene. In strong contrast to the findings described for the ydr109cΔ strain, the metabolite profile of the mpa43Δ strain showed only few significant metabolite level changes compared with the wild-type strain, and the mpa43Δ and wild-type metabolite profiles were not clearly separable using PCA (data not shown). Importantly, we could not detect an increase in free ribulose (or any other pentose) or ribitol levels in the mpa43Δ strain, suggesting that Ydr109c and Mpa43 are not isozymes.

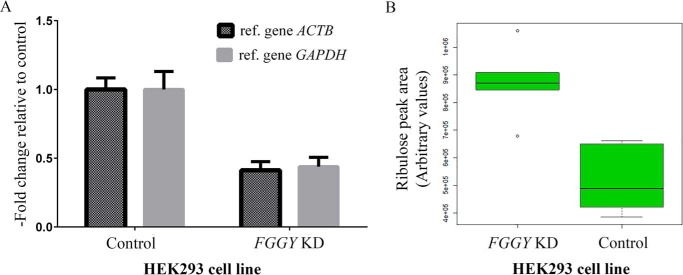

FGGY Silencing in Human Embryonic Kidney Cells Leads to Increased Ribulose Levels under Certain Conditions

The human genome contains a homolog of the yeast YDR109C gene, designated FGGY (40% identity at the amino acid sequence level). As for the yeast protein, the molecular and biological roles of the human FGGY protein remain largely unknown. Based on our results in the yeast model, we searched for ribulose or other pentoses in metabolite extracts derived from HEK293 cells and from the hepatocyte cell line PH5CH8 using a targeted ZIC-HILIC-MS method. Extracted ion chromatograms (m/z = 149.0445) did not reveal the presence of ribulose in either the HEK293 or PH5CH8 cells when cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 5 mm d-glucose (in addition to the 25 mm glucose already contained in the DMEM formulation). The analyses were repeated in a HEK293 cell line stably expressing an FGGY-specific small hairpin RNA (shRNA) and in PH5CH8 cells transfected with FGGY-specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Despite a knockdown efficiency of about 60% in both cell types at the mRNA level (Fig. 4A and data not shown), ribulose could not be detected in any of the conditions tested.

FIGURE 4.

Ribulose accumulates in FGGY knockdown human cells exposed to ribitol. HEK293 FGGY knockdown (KD) and control cells were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10 mm ribitol. Metabolites and total RNA were extracted 41 h after addition of ribitol, and pentoses were measured using a targeted ZIC-HILIC-MS method. A, FGGY knockdown efficiency was evaluated using quantitative RT-PCR. The relative expression level of FGGY was estimated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The expression level of the FGGY gene in each sample was either normalized to reference gene ACTB or GAPDH. Means and standard deviations of 12 (FGGY KD cells) and 11 (control cells) biological replicates are shown. B, box-and-whisker plot representing the area of the ribulose peak (m/z 149.0445, [M − H]− ion in the negative mode). Statistical analysis by Welch's t test confirmed that the mean ribulose peak area was significantly increased in the FGGY KD cells compared with the control cells (p value = 0.0005; six biological replicates for each cell line). KD, knockdown.

Given that ribulose was shown not to be taken up by human fibroblasts (25), we supplemented the basal cell culture medium with the potential ribulose precursor ribitol, both at a concentration of 5 or 10 mm, for the PH5CH8 and HEK293 cells. In addition, we tested supplementation with 5 mm d-arabinose for the HEK293 cells. d-Arabinose and ribitol can be metabolized in bacteria via pathways that include d-ribulose as an intermediate (26, 27). Although we detected intracellular d-arabinose in the HEK293 cells cultivated in the presence of this pentose, we did not detect any intracellular ribulose 48 h after the addition of d-arabinose, without or with FGGY silencing. In contrast, in HEK293 cells cultivated in the presence of ribitol, we detected ribulose, and the latter accumulated to higher levels in cells knocked down for FGGY (Fig. 4B). When non-labeled ribitol was replaced by [U-13C]ribitol in these experiments, a +5 m/z shift was observed for the peak co-eluting with a ribulose standard (data not shown), confirming the identity of the peak as ribulose and showing that the ribulose measured derived from the supplemented ribitol under the cultivation conditions used. PH5CH8 cells cultivated in the presence of ribitol did not produce measurable amounts of ribulose, even when FGGY was knocked down (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that free ribulose is not produced in detectable amounts by the cell lines tested here under standard cultivation conditions, but that in certain cell types ribitol can be oxidized to ribulose. The increased ribulose levels measured in HEK293 FGGY knockdown cells cultivated in the presence of ribitol also confirm that FGGY can use ribulose as a substrate in a living cell.

Recombinant Yeast Ydr109c and Human FGGY Specifically Convert d-Ribulose to d-Ribulose 5-Phosphate in the Presence of ATP

Our findings in yeast and mammalian cells suggested that ribulose is an endogenous substrate of the yeast Ydr109c and human FGGY proteins. Additionally being members of the FGGY family of sugar kinases, this strongly indicated that Ydr109c and FGGY are ribulokinases. To confirm this hypothesis and find out whether the enzymes act on d-ribulose or l-ribulose (not separated by our liquid chromatography method preceding the MS analysis), we expressed recombinant N-terminally His-tagged Ydr109c and FGGY in a bacterial system and purified the proteins by Ni2+ affinity chromatography for subsequent enzyme activity assays.

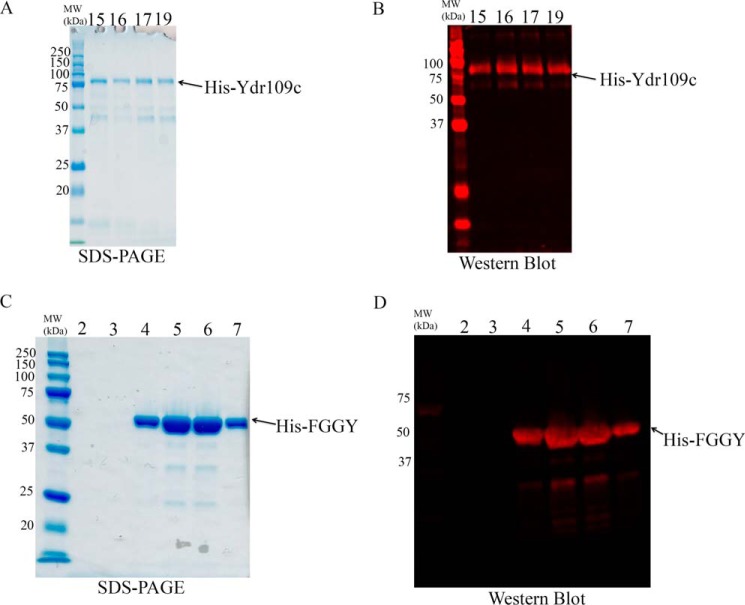

The purified His-Ydr109c protein generated a band at the expected size (83 kDa) as shown by SDS-PAGE analysis and Western blotting using an anti-His antibody (Fig. 5, A and B). Using the PK/LDH coupled spectrophotometric assay, we tested the putative kinase activity of recombinant Ydr109c on 19 different sugars or sugar derivatives (9 pentoses, 4 sugar alcohols, d-glucose, d-gluconate, d-glycerol, d-ribulose-5-P, d-ribose-1-P, and d-ribose-5-P) at a concentration of 1 mm (Table 1). Enzymatic activity was only detected in the presence of d-ribulose. With this substrate, the enzyme showed Michaelis-Menten kinetics, and we determined a Km of 217 ± 15 μm and a Vmax of 22 ± 2 μmol·min−1·mg protein−1 (means ± S.D., n = 3). The recombinant His-Ydr109c protein was very unstable and lost activity upon freezing and thawing or during prolonged purification procedures. Therefore, enzyme activity assays with recombinant His-Ydr109c were carried out within 24 h after affinity purification, without prior desalting, keeping the protein at 4 °C throughout the purification procedure and until the measurements.

FIGURE 5.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analyses of recombinant His-Ydr109c and His-FGGY proteins. The indicated purified His-Ydr109c (A and B) and His-FGGY (C and D) fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining and Western blotting using an antibody directed against the N-terminal polyhistidine tag fused to each of the recombinant proteins. Fractions eluted from an Ni2+ affinity column were analyzed either before (His-Ydr109c) or after desalting (His-FGGY). The expected molecular mass of the His-Ydr109c and His-FGGY proteins is 82.8 and 63.7 kDa, respectively. MW, molecular mass.

TABLE 1.

Substrate specificity of the carbohydrate kinase activity of Ydr109c and FGGY

The kinase activities of the recombinant purified His-Ydr109c and His-FGGY proteins were measured spectrophotometrically using the PK/LDH assay with 19 different sugars or sugar derivatives (all at a concentration of 1 mm). Enzymatic activities were corrected by control assays run in the absence of carbohydrate substrate. The results shown are mean relative activities ± S.D. resulting from three replicative measurements. ND, not detected; S.D., standard deviation.

| Substrate | FGGY activity | Ydr109c activity |

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| d-Ribulose | 100 ± 2 | 100 ± 3 |

| l-Ribulose | 8 ± 1 | ND |

| Ribitol | 21 ± 1 | ND |

| d-Xylulose | 1 ± 0.3 | ND |

| l-Xylulose | 1 ± 0.3 | ND |

| d-Glucose | ND | ND |

| Arabitol | ND | ND |

| Erythritol | ND | ND |

| l-Arabinose | ND | ND |

| d-Arabinose | ND | ND |

| d-Ribose | 1 ± 0.3 | ND |

| Glycerol | ND | ND |

| d-Ribulose 5-phosphate | ND | ND |

| Gluconate | ND | ND |

| 2-Deoxy-d-ribose | ND | ND |

| d-Lyxose | ND | ND |

| d-Ribose 5-phosphate | ND | ND |

| d-Mannitol | ND | ND |

| d-Ribose 1-phosphate | ND | ND |

The human recombinant His-FGGY protein was, unlike its yeast homolog, very stable. SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analyses of the fractions collected after Ni2+ affinity purification and desalting showed a major band at about 50 kDa, i.e. below the expected mass of 64 kDa for the His-FGGY protein (Fig. 5, C and D). LC-MS/MS analysis after trypsin digestion of the purified protein preparation confirmed, however, the sequence identity of the protein, the detected peptides showing the best match to the Q96C11-1 (UniProt) sequence, with 76% sequence coverage (data not shown). The reason for protein migration at a lower apparent molecular mass during SDS-PAGE remains unknown. To determine the substrate specificity of the enzyme, we screened the same 19 compounds that we used for Ydr109c substrate specificity testing, at two different concentrations (100 μm and 1 mm). The recombinant human FGGY protein clearly showed the highest activity with d-ribulose, but it also phosphorylated ribitol and l-ribulose at lower rates (Table 1). We determined a Km of 97 ± 25 μm and a Vmax of 5.6 ± 0.4 μmol·min−1·mg protein−1 (means ± SDs, n = 3) for the d-ribulokinase activity and a Km of 1468 ± 541 μm and a Vmax of 2.4 ± 0.3 μmol·min−1·mg protein−1 (means ± S.D., n = 4) for the ribitol kinase activity. Human FGGY is thus 35-fold more efficient as a d-ribulokinase than as a ribitol kinase. Purified human His-FGGY protein was found to be enzymatically active even after 1 year of storage at −80 °C.

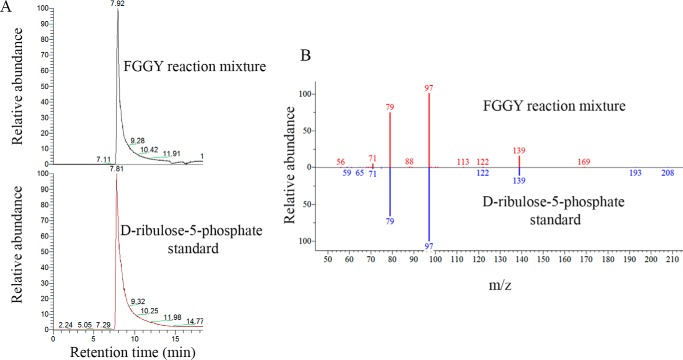

The identity of the pentose phosphate product formed by human recombinant FGGY when incubated with its preferred substrate d-ribulose was confirmed by analyzing the enzymatic reaction mixture by LC-MS/MS. A major compound contained in this mixture displayed a detected mass corresponding to the theoretical mass of ribulose-5-P, co-eluted with a d-ribulose 5-phosphate analytical standard, and showed the same MS2 fragmentation pattern as this analytical standard (Fig. 6, A and B). After incubation of recombinant FGGY with ribitol or l-ribulose (both at a concentration of 1 mm), we also detected the masses of the expected ribitol 5-phosphate (theoretical m/z 231.0264; detected m/z 231.0273) or l-ribulose 5-phosphate (theoretical m/z 229.0108; detected m/z 229.0116) products in the reaction mixtures (data not shown); further support (co-elution and MS2 spectrum match with standards) for these compound identities could, however, not be gathered as appropriate analytical standards were not commercially available.

FIGURE 6.

Confirmation of the product of the reaction catalyzed by human FGGY as ribulose 5-phosphate. A, a reaction mixture resulting from the PK/LDH coupled d-ribulokinase assay was analyzed using ZIC-HILIC-ddMS2. The extracted ion chromatogram (m/z 229.0108, negative ionization mode) shows a peak at retention time 7.92 min that co-elutes with the external analytical standard d-ribulose 5-phosphate. B, head-to-tail comparison of the MS2 fragmentation pattern of the parent ion m/z 229.0108 eluting at 7.92 min during analysis of the enzyme assay mixture and of the co-eluting ion from the external d-ribulose 5-phosphate standard.

Yeast Ydr109c and Human FGGY Are Homologs of a Proteobacterial d-Ribulokinase Involved in Ribitol Metabolism

A specific d-ribulokinase was first reported in Klebsiella aerogenes by Neuberger et al. (28), and the gene encoding this enzyme (rbtK) was cloned in 1998 from Klebsiella pneumoniae (27). Certain enteric bacteria, including many Klebsiella strains, but only a few Escherichia coli strains (e.g. E. coli C, but not E. coli K12 and B), can use the pentitols d-arabitol and ribitol as sole carbon sources. Although both pentitols are catabolized via oxidation followed by phosphorylation, specific transporters, repressors, and enzymes encoded by two different operons govern the metabolism of each of these pentitols. The K. pneumoniae ribitol operon includes a ribitol transporter, a ribitol dehydrogenase, the d-ribulokinase, and a repressor that is induced by d-ribulose (27). The existence of this ribitol operon greatly helped us to identify “true” d-ribulokinases in other bacterial species, and we found d-ribulokinase genes clustering with ribitol dehydrogenase genes in other γ-proteobacteria, α-proteobacteria, and the β-proteobacterium Burkholderia sp. Ch1-1 using the SEED viewer browser (29). The K. pneumoniae d-ribulokinase sequence (UniProt A6TBJ4) was also used to identify d-ribulokinase ortholog candidates in eukaryotic species using blastp searches. This analysis showed that d-ribulokinase is conserved in many animal species, fungi, and plants with close to 40% amino acid sequence identity or more to the bacterial sequence. Among those ortholog candidates, S. cerevisiae Ydr109c shared 39% amino acid sequence identity (E-value of 6e-114), and human FGGY (RefSeq isoform b or UniProt Q96C11-1) shared 42% amino acid sequence identity (E-value of 7e-143) with the bacterial d-ribulokinase protein. The S. cerevisiae protein Mpa43 also aligned with the latter but showed lower amino acid sequence conservation (25% identity; E-value of 2e-31).

Fig. 7 shows a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of d-ribulokinase candidate sequences selected across different kingdoms of life (γ-, α-, and β-proteobacteria, yeast, Drosophila, zebrafish, Arabidopsis, mice, and humans). It also includes the yeast Mpa43 protein sequence. Despite the considerable evolutionary distance between most of the chosen species, highly conserved sequence motifs can be found over the entire length of the d-ribulokinase sequence. Strikingly, the yeast Ydr109c protein shows, however, an approximate 20-amino acid N-terminal sequence extension and an approximate 100-amino acid sequence insertion toward the C-terminal extremity that are found in none of the other d-ribulokinase protein sequences analyzed. Although the N-terminal sequence may be involved in targeting the protein to a specific subcellular compartment, we cannot currently speculate on the role of the C-terminal insertion. Using the strain sequence alignment function in SGD, we found that the 20-amino acid N-terminal extension and the 100-amino acid C-terminal insertion are highly conserved within the S. cerevisiae species. Using the fungal sequence alignment function in SGD, it appears that Ydr109c homologs in other budding yeasts such as Saccharomyces paradoxus, Saccharomyces bayanus, Saccharomyces uvarum, and Saccharomyces mikatae also include an N-terminal extension and C-terminal insertion that is absent from bacterial, animal, and plant d-ribulokinase proteins (in many of the budding yeast species analyzed, the Ydr109c homologous proteins have a size of more than 700 amino acids as opposed to the smaller protein size of around 550 amino acids displayed by bacterial, animal, and plant d-ribulokinase proteins); these additional sequences show, however, as opposed to the rest of the Ydr109c protein sequence, no significant sequence similarity between the different yeast species analyzed. These observations suggest that the additional sequences found in the S. cerevisiae Ydr109c protein are “real” and do not result from erroneous gene structure annotation or genome sequencing errors. This was further consolidated by the fact that our own sequencing of the Ydr109c ORF that we PCR-amplified from S. cerevisiae genomic DNA yielded a result that was in perfect agreement with the sequence contained in the SGD database.

FIGURE 7.

Multiple sequence alignment of d-ribulokinase proteins across different kingdoms of life. Conserved amino acids are highlighted in different shades of blue according to the degree of conservation (the darker the shading the higher the conservation). The top 20 specificity determining positions (SDPs) are highlighted in red. The number above the SDPs indicates the ranking based on the scores calculated by the GroupSim+ConsWin software (number 1 corresponds to the SDP with the highest score). Amino acids predicted to interact with the pentose substrate based on structural homology models of the yeast Ydr109c and human FGGY proteins are highlighted in yellow. The UniProt identifiers of the protein sequences shown are A6TBJ4 (K. pneumoniae), B6XGJ3 (Providencia alcalifaciens), M9RKB9 (Octadecabacter arcticus), B9K586 (Agrobacterium vitis), I2IVR0 (Burkholderia sp. Ch1-1), P53583 (Mpa43, S. cerevisiae), Q04585 (Ydr109c, S. cerevisiae), Q96C11 (H. sapiens), A2AJL3 (Mus musculus), Q6NUW9 (Danio rerio), Q9VZJ8 (Drosophila melanogaster), and F4JQ90 (Arabidopsis thaliana). Note that the alignment includes the yeast Mpa43 protein, which, unlike the other proteins shown, most likely does not act as a d-ribulokinase. Accordingly, the d-ribulokinase signature motif defined in this study (TCSLV sequence highlighted by the box frame) is not strictly conserved in the MPA43 protein.

Zhang et al. (3) performed a detailed bioinformatics analysis of proteins belonging to the FGGY carbohydrate kinase family to better understand the evolutionary mechanisms underlying functional diversification in this family. They assembled a confidently annotated reference set (CARS) of 446 FGGY proteins with high quality functional annotations based not only on sequence homology but also on experimental evidence (if available) and on genomic as well as pathway context. The CARS protein set comprised only three eukaryotic FGGY family members (1 glycerol kinase and 2 xylulose kinases), all the other proteins were of bacterial origin. The CARS proteins were used for phylogenetic analyses and to predict amino acid residue positions that are important for the recognition of a specific substrate within isofunctional groups of proteins (also referred to as specificity-determining positions or SDPs). Here, we extended the phylogenetic analysis of this CARS protein set by adding the protein sequences that we confidently identified as d-ribulokinases and used for the MSA shown in Fig. 7, including the S. cerevisiae Ydr109c and human FGGY proteins. As expected, the resulting phylogenetic tree displayed a very similar topology to the one constructed by Zhang et al. (3), with most of the proteins forming tight clusters according to their enzymatic function (e.g. glycerol kinase cluster, xylulokinase cluster) and suggesting a divergent evolution model (supplemental Fig. S1). We also found a more complex branching for the l-ribulokinase (AraB) group whose members split into several subgroups interspersed with the gluconokinase and d-ribulokinase groups. All the d-ribulokinase sequences that we included additionally in the phylogenetic analysis cluster with the d-ribulokinase group that evolved from one of the l-ribulokinase subgroups (supplemental Fig. S1). This suggests that the prokaryotic and eukaryotic d-ribulokinases evolved from the same common ancestor by divergent evolution.

We further extended our d-ribulokinase sequence analyses by applying the GroupSim+ConsWin method (30) for the identification of sequence positions determining the sugar substrate specificity (SDPs) of d-ribulokinase proteins. The GroupSim method predicts SDPs based on sequence information only. ConsWin is a heuristic that can be combined with the GroupSim method to improve SDP predictions by taking into account sequence conservation of neighboring amino acids. SDP predictions were made by applying GroupSim+ConsWin to the MSA built from our extended CARS dataset (enriched in d-ribulokinase sequences), where sequences were grouped according to the high quality functional annotations (for isofunctional groups spanning multiple subgroups only the subgroup with the highest number of protein sequences was kept; see under “Experimental Procedures” for more details). The top 20 SDPs identified for the yeast and human d-ribulokinases (Ydr109c and FGGY, respectively) are highlighted in red in Fig. 7. The majority of these SDPs correspond to residues that are highly conserved between prokaryotic and eukaryotic d-ribulokinases (Fig. 7). It should be noted that among the 12 SDPs with strictly conserved residues in all of the d-ribulokinase sequences shown in Fig. 7, three positions contain different residues in the yeast Mpa43 protein (Ser to Val, Cys to Gly, and Ala to Ser substitutions), which, together with the absence of ribulose accumulation in the yeast mpa43Δ deletion strain, further supports that this protein most likely does not function as a d-ribulokinase. As described below, these predictions, as well as structural predictions provided the basis for the identification of a sequence motif that appears to be specific for d-ribulokinases.

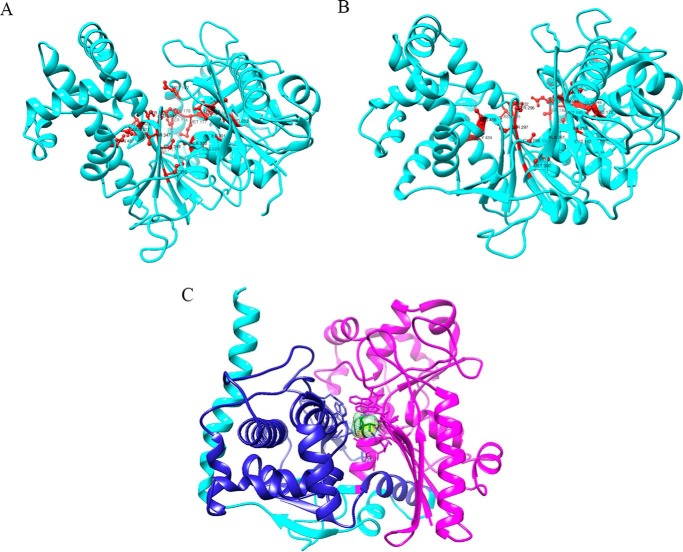

Structural Homology Modeling of Yeast and Human d-Ribulokinases and Definition of a d-Ribulokinase Signature Motif

Three-dimensional structural homology models of the yeast Ydr109c and human FGGY proteins were generated using the crystal structure of a Yersinia pseudotuberculosis FGGY carbohydrate kinase (PDB code 3L0Q chain A and 3GGA chain A for FGGY and Ydr109c, respectively) as a template (Fig. 8). Of the 20 proteins with an FGGY_N domain for which three-dimensional structures have been deposited in PDB, this Y. pseudotuberculosis protein Q665C6 has the highest sequence similarity to the yeast Ydr109c and human FGGY proteins (39 and 51% amino acid sequence identity, respectively). A d-xylulose molecule is contained in the putative active site of the PDB 3L0Q crystal structure, and the protein is annotated as a xylulose kinase in the PDB. Sequence analysis clearly suggests, however, that this protein is in fact a d-ribulokinase, given the high sequence similarity with the yeast Ydr109c and human FGGY proteins and the presence of the TCSLV motif, identified here as a d-ribulokinase signature motif as described below.

FIGURE 8.

Structural homology models of yeast Ydr109c and human FGGY proteins. A, homology models of the Ydr109c protein (A) and the FGGY protein (B) created using template structures from PDB entries 3GG4 chain A and 3L0Q chain A, respectively, of Y. pseudotuberculosis d-ribulokinase. Residues corresponding to the top 20 specificity determining positions predicted in this study are highlighted in red. C, homology model of the FGGY protein in complex with the ligand d-xylulose (light green color). The FGGY_C and FGGY_N domains are highlighted in dark blue and pink, respectively.

We used the available ligand information from the 3L0Q structure to position d-xylulose within our human FGGY structural models (Fig. 8C) and to identify the localization of the active site as well as amino acid residues important for substrate binding and/or catalysis. For yeast Ydr109c, a molecular docking approach was used to determine both ligand position and orientation, as the original structure of 3GGA chain A was not bound to any ligand molecule. As for other FGGY carbohydrate kinases, a catalytic cleft is formed at the interface between the two conserved actin-like ATPase domains (Pfam domains FGGY_N and FGGY_C). It has been shown for other members of the family that the sugar substrate binds deeply within the catalytic pocket and interacts mainly with residues of the FGGY_N domain whereas the ATP co-substrate binds more toward the opening of the cleft interacting with both the FGGY_N and FGGY_C domains (31). Accordingly, the xylulose ligand in our d-ribulokinase structural models contacts only residues of the FGGY_N domain (Fig. 8C for the human protein; not shown for the yeast protein). Using the human FGGY homology model, we found that the residues Thr-86, Ile-259, Asp-260, Ala-261, and His-262 can take part in van der Waals interactions and that Cys-87, Asp-260, and Glu-328 have the potential to form hydrogen bonds with the substrate (residues highlighted in yellow in Fig. 7). Based on the Ydr109c homology model, the residues Cys-117, Ile-301, and Asp-302 are potentially involved in van der Waals interactions and Thr-116, Cys-117, Lys-224, Asp-302, Tyr-304, Glu-378, and Arg-449 potentially form hydrogen bonds with the substrate (also highlighted in yellow in Fig. 7). It can be seen in Fig. 7 that all the residues predicted to be important for sugar substrate binding using the structural models coincide or are found in close proximity to identified SDPs. Mapping the top 20 SDPs onto the human and yeast homology models, it can also be seen in Fig. 8, A and B, that most of them, although sometimes distant from each other in sequence, are located in or near the catalytic cleft in the structural models.

Two highly conserved motifs in the MSA shown in Fig. 7 stand out by featuring residues important for substrate specificity or binding as predicted by both the SDP or structural modeling approaches: the TCSLV motif (starting with Thr-86 in FGGY and Thr-116 in Ydr109c) and the IDA(H/Y) motif (starting with Ile-259 in FGGY and Ile-301 in Ydr109c). Using the master MSA used for construction of the phylogenetic tree, we found that the TCSLV motif is strictly conserved in the entire d-ribulokinase cluster of sequences but is not found in other isofunctional groups of the FGGY protein family, whereas the IDA(H/Y) motif was also retrieved in a few l-ribulokinase sequences. The TCSLV motif was further validated as a d-ribulokinase signature motif using a second master MSA based on more than 600 reviewed FGGY family members retrieved from UniProt (see “Experimental Procedures”). Interestingly, the Val residue of this signature motif is replaced by an Ala residue in the Mpa43 protein. This second master MSA also allowed us to confirm the existence of multiple distinctive subgroups within the l-ribulokinase functional group and to identify additional conserved sequence motifs distinguishing the l-ribulokinase subgroups in a homologous position to the TCSLV motif in the d-ribulokinase group (namely TGTST, TSST, TGSSP, TGSTP, MMHGY, and TACTM). Zhang et al. (3) also made SDP predictions and, based on structural information available in PDB, selected five (generally non-consecutive) SDPs as “signature residues” for all the subgroups in their FGGY CARS dataset. Of the five SDPs selected for the d-ribulokinase subgroup (Thr, Cys, Glu, Ala, and Tyr), three (Thr, Glu, and Ala) coincide with SDPs predicted using a different method in this study (see under “Experimental Procedures”), and two (Thr and Cys) are comprised in the d-ribulokinase signature motif defined and validated here using protein datasets containing a higher number of evolutionary more distant d-ribulokinase sequences than in the study by Zhang et al. (3).

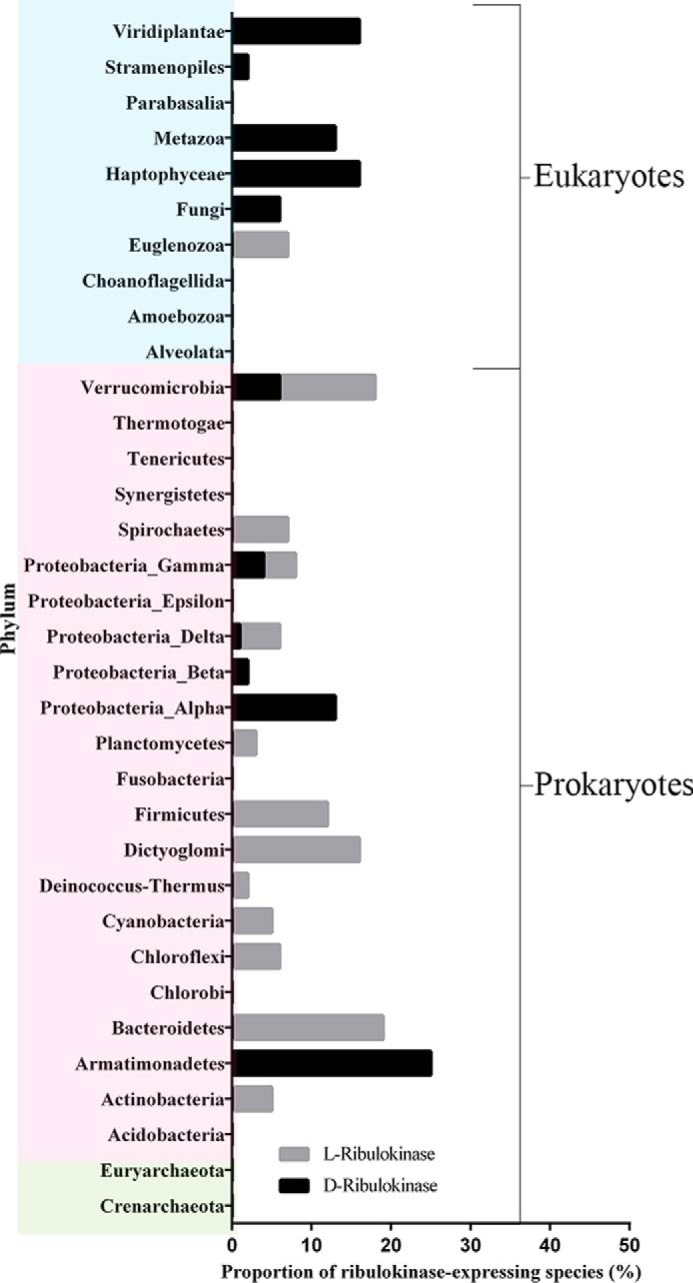

Finally, using the described d-ribulokinase and l-ribulokinase sequence motifs, we analyzed the phylogenetic spread of these kinases based on FGGY_N domain sequences retrieved for 34 different phyla from the Pfam database, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Strikingly, as can be seen in Fig. 9, d-ribulokinase is much more widely conserved in eukaryotes (including animals, plants, and fungi), whereas l-ribulokinases are more broadly distributed in prokaryotes. In prokaryotes, d-ribulokinase is found only in proteobacterial lineages as well as in Verrucomicrobia and Armatimonadetes. No ribulokinase homologs (neither d- nor l-) were found in Archaea.

FIGURE 9.

Phyletic spread of d-ribulokinase and l-ribulokinases. The taxonomic distribution of d- and l-ribulokinase proteins was determined using the FGGY_N domain sequences present in the Pfam database at the time of analysis and the d-ribulokinase and l-ribulokinase motifs defined in this study (TCSLV and TGTST, TSST, TGSSP, TGSTP, MMHGY, and TACTM, respectively). Eukaryotic, bacterial, and archaeal phyla are represented on blue, pink, and green backgrounds, respectively.

Discussion

Identification of YDR109C and FGGY as Genes Encoding a Specific Eukaryotic d-Ribulokinase

In this study, we aimed at identifying the molecular and biological roles of two homologous proteins of unknown function (Ydr109c in yeast and FGGY in humans), both of which are members of the FGGY protein family of carbohydrate kinases. To reach this objective, we started by comparing the polar metabolite profiles of yeast cells deleted in the YDR109C gene and of wild-type control cells using non-targeted LC-HRMS or LC-MS/MS. One of the most prominent and robust changes, observed in both a prototrophic and an auxotrophic genetic background and partially rescued when restoring YDR109C expression in the deletion strain, was the accumulation, in the ydr109cΔ strain, of a pentose identified as ribulose by comparing elution time, accurate mass, and MS2 fragmentation pattern with those of a ribulose standard. Ribulose did not accumulate in a yeast strain deleted for a closely related protein encoded by the S. cerevisiae genome (Mpa43), suggesting that Ydr109c is the only kinase responsible for free ribulose conversion in this organism. Labeling experiments in which d-[U-13C]glucose was used as the sole carbon source confirmed that yeast cells can produce free ribulose from d-glucose and that this pentose accumulates upon YDR109C deletion. In contrast, we could not detect free ribulose in the two human cell lines tested in this study (HEK293 and PH5CH8), even after silencing of the YDR109C homologous gene FGGY. In the HEK293 cells, but not in the PH5CH8 cells, ribulose became detectable upon supplementation of the cultivation medium with ribitol. Under those conditions, FGGY knockdown led to increased ribulose levels in the HEK293 cells. Finally, in vitro enzymatic assays with recombinant purified Ydr109c and FGGY proteins confirmed that both act as ATP-dependent sugar kinases and showed that d-ribulose is by far the best substrate for those enzymes. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that Ydr109c and FGGY phosphorylate d-ribulose in budding yeast and human cells, respectively, and associate the eukaryotic d-ribulokinase activity, which had been reported to exist in guinea pig liver before (32, 33), with a protein sequence. Although numerous other metabolites were significantly changed in the ydr109cΔ prototrophic strain compared with the corresponding wild-type strain in addition to ribulose, the facts that we did not observe a majority of those other changes in a different genetic background and that they were not restored in a prototrophic rescue strain do not allow us to firmly associate those changes with the YDR109C gene based on our current results.

d-Ribulokinase Is the Major Ribulokinase in Eukaryotes, while l-Ribulokinase Is More Widely Distributed in Prokaryotes

Prior to this study, a specific d-ribulokinase involved in ribitol metabolism had been cloned from K. pneumoniae (27). The d-ribulokinases from Aerobacter aerogenes (34) and K. aerogenes (28) have been extensively purified and characterized. The enzyme was shown to be active as a homodimer, and Km values for d-ribulose of 85 and 400 μm were reported for the Aerobacter and Klebsiella enzymes, respectively. A Vmax of 71 μmol·min−1·mg protein−1 was found for the Klebsiella d-ribulokinase, and this enzyme showed low side activities with ribitol (Km of 220 mm, Vmax of 12 μmol·min−1·mg protein−1) and d-arabitol (Km of 140 mm, Vmax of 6.6 μmol·min−1·mg protein−1) (28). The kinetic properties for d-ribulose are similar to the ones determined in this study for the S. cerevisiae and human d-ribulokinases (Km of 217 μm and Vmax of 22 μmol·min−1·mg protein−1 for Ydr109c; Km of 97 μm and Vmax of 5.6 μmol·min−1·mg protein−1 for FGGY). For the human enzyme, we also found lower but detectable activities with ribitol and l-ribulose; d-arabitol was not tested as it could not be obtained commercially at the time of this study. The highly similar enzymatic properties shared by those enzymes from evolutionary divergent organisms, in addition to the high sequence identity, support that they are orthologous proteins.

The molecular identification of the eukaryotic d-ribulokinase allowed us to incorporate eukaryotic d-ribulokinase sequences into phylogenetic analyses. In agreement with an extensive previous study on the evolution of functional specificities of prokaryotic members of the FGGY carbohydrate kinase family (3), we found that eukaryotic d-ribulokinases, just as the bacterial d-ribulokinases, have evolved from an l-ribulokinase (AraB) FGGY subgroup. Based on our sequence and structural analyses, we also defined and validated a d-ribulokinase signature motif (TCSLV), which can now be used with high confidence to functionally identify FGGY protein sequences as d-ribulokinase. Using this motif, we found that d-ribulokinase is conserved in only a few bacterial lineages, although it is widespread in eukaryotes (see Fig. 9). Notable exceptions of eukaryotic species that do not encode a d-ribulokinase are Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Caenorhabditis elegans, and trypanosomatid species. By contrast, l-ribulokinase, which is required for l-arabinose metabolism in bacteria, is much more broadly conserved in prokaryotes than d-ribulokinase, but it is not found in eukaryotic species, except for trypanosomatid species such as Leptomonas, Trypanosoma, and Leishmania (Fig. 9); the genomes of S. pombe and C. elegans do not encode either l- or d-ribulokinase. In summary, while l-ribulokinase is more broadly distributed in prokaryotes, d-ribulokinase is more broadly conserved in eukaryotes. Bacterial species that encode d-ribulokinase can also encode l-ribulokinase (e.g. K. pneumoniae), but many bacterial species encode only l-ribulokinase. Similarly, the trypanosomatid species that encode l-ribulokinase do not encode d-ribulokinase; unlike for many bacteria, however, the eukaryotic genomes that contain a d-ribulokinase gene do not contain an l-ribulokinase gene. So, whereas bacterial genomes can contain two types of ribulokinases, eukaryotic genomes generally encode either the d- or the l-ribulokinase form (Fig. 9).

Although this study on eukaryotic proteins and previous studies on bacterial proteins (28, 34) have shown that d-ribulokinase is highly specific for d-ribulose, l-ribulokinase is much more promiscuous in terms of sugar substrate specificity. E. coli l-ribulokinase (AraB) for example has been reported to use d-ribulose with a catalytic efficiency that is only 2–3-fold lower than its best substrate l-ribulose (35). In addition, AraB showed significant activity with l-xylulose, l-arabitol, and ribitol and also acted on d-xylulose (35). This enzyme could therefore also be designated 2-ketopentokinase. The substrate promiscuity of l-ribulokinase as well as the significant sequence similarity between l-ribulokinase and d-ribulokinase are certainly the reasons for many misannotations of d-ribulokinases as l-ribulokinases and vice versa in gene and protein databases. Human FGGY, for example, displays more than 40% sequence identity with the K. pneumoniae d-ribulokinase, but it also shares 25% sequence identity with the E. coli l-ribulokinase. Our enzymatic characterizations have clearly established the yeast and human ribulokinases as d-ribulokinases. This study, and more particularly the d-ribulokinase sequence signature that we defined, should therefore help to correct the numerous database misannotations of FGGY protein family members and more specifically of the ribulokinases. Although the numerous bacterial species that only encode an l-ribulokinase may not be able to grow on ribitol due to the lack of an inducible ribitol utilization pathway, including the specific d-ribulokinase (see below), the substrate promiscuity of their l-ribulokinase may ensure that free d-ribulose can be metabolized to a certain degree. Conversely, eukaryotic species, which for the most part only encode the more specific d-ribulokinase, should have a good metabolic capacity for d-ribulose, but more poorly, if at all, metabolize ribitol or l-ribulose.

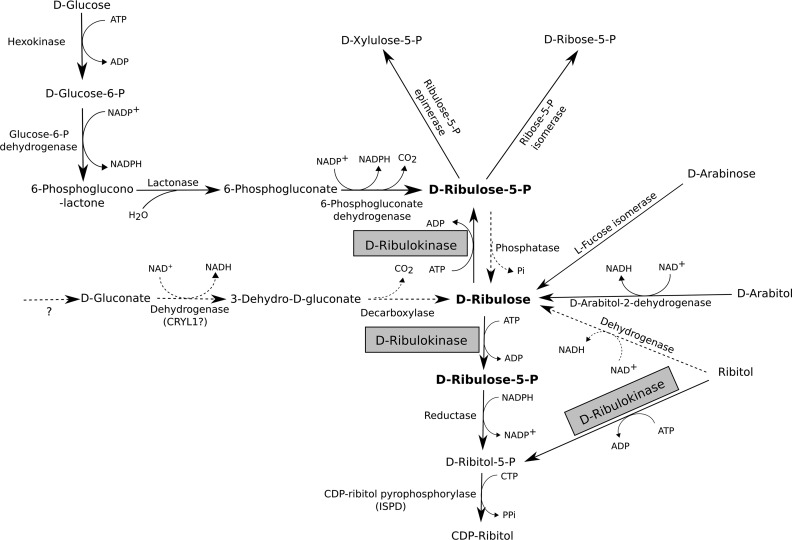

Known and Putative Physiological Roles of d-Ribulokinase in Bacteria and Eukaryotes

Fig. 10 shows an overview of known and hypothetical reactions and pathways leading to the formation and metabolization of d-ribulose in various organisms. In K. pneumoniae and other enterobacteria that can use ribitol as the sole carbon source (36), the d-ribulokinase gene is located in a ribitol utilization operon that contains in addition a ribitol transporter, a ribitol dehydrogenase, and a repressor; d-ribulose is an inducer of this operon (27). In addition, Elsinghorst and Mortlock (26) reported in 1988 that in E. coli B a d-ribulokinase gene is contained in the l-fucose regulon. The latter encodes the enzymes required for l-fucose utilization but can also be induced by d-arabinose, which can then be metabolized to d-ribulose and d-ribulose-5-P via l-fucose isomerase and d-ribulokinase, respectively (26). In the bacterial species that encode d-ribulokinase, this enzyme thus allows to direct carbon from ribitol or d-arabinose to the pentose phosphate pathway via phosphorylation of the d-ribulose intermediate that is formed in the respective sugar utilization pathways. We found that d-ribulokinase sequences contained in either the ribitol or some enterobacterial l-fucose operons share high sequence similarity with yeast Ydr109c and human FGGY and contain the d-ribulokinase signature motif defined in this study.

FIGURE 10.

Known and putative routes involved in d-ribulose metabolism. Overview of reactions and pathways leading to the production or utilization of d-ribulose. Some of the pathways shown are only known to occur in certain microorganisms, as detailed in the main text. Dotted arrows represent hypothetical reactions for which no corresponding gene has been identified yet in any organism. The d-ribulokinase enzyme, for which the eukaryotic gene has been identified in this study, is highlighted.

The only previous reports on a eukaryotic d-ribulokinase activity, in our knowledge, go back to the early 1960s, when Kameyama and Shimazono (32, 33) detected such an activity in guinea pig liver. A corresponding gene has not been cloned since. In these early studies, the authors had become interested in the metabolism of d-ribulose in mammals after having found that d-ribulose can be formed from d-gluconate in guinea pig liver extracts (37). We did not find subsequent studies on this putative pathway, but d-gluconate to d-ribulose conversion may be initiated by a side activity of l-gulonate 3-dehydrogenase (encoded by the CRYL1 gene), an enzyme involved in the pentose pathway for d-glucuronate catabolism in mammals (38, 39). The subsequent step in the pentose pathway is the decarboxylation of 3-dehydro-l-gulonate to l-xylulose (40); a similar reaction could convert 3-dehydro-d-gluconate to d-ribulose. The gene encoding 3-dehydro-l-gulonate decarboxylase has not yet been identified. The mechanism of formation of d-gluconate in mammalian cells, if it occurs at all, also remains unclear. The existence of a mammalian pathway for d-ribulose formation from d-gluconate therefore remains highly speculative.

Using LC-MS-based metabolite profiling and isotopic labeling, we could measure d-ribulose formation from externally supplemented ribitol in human HEK293 cells but not from glucose. By contrast, in S. cerevisiae, we were able to detect formation of d-ribulose from glucose, although the conversion of ribitol to d-ribulose was not observed in this organism. Our results suggest that, whereas yeast cells constantly produce detectable amounts of free d-ribulose under standard cultivation conditions from glucose, this may not be the case for mammalian cells. However, our observations in the HEK293 cells suggest that ribitol can serve as a precursor for d-ribulose at least in certain mammalian cell types; d-ribulose was not detected in PH5CH8 cells (this study) or human fibroblasts (25) cultivated in the presence of ribitol, and no ribitol dehydrogenase activity could be detected in human erythrocyte lysates (25). Ribitol dehydrogenase activity has, however, been measured during early studies with partially purified enzyme preparations from rat liver (41) and from guinea pig liver mitochondria (42). Comparing gene expression profiles of HEK293 and PH5CH8 cells could be a promising strategy to identify the putative dehydrogenase responsible for the oxidation of ribitol to d-ribulose in certain mammalian cell types. The prototrophic yeast strain used in this study did not grow in rich medium (yeast extract and peptone) supplemented with 100–200 mm ribitol instead of 100–200 mm glucose. Moreover, when adding 5 mm [U-13C]ribitol to minimal medium containing 2% glucose, we could not detect any 13C-labeled ribulose in cellular extracts prepared from the yeast cultivations, neither for the wild-type nor for the ydr109cΔ strains. This suggests that, unlike for certain mammalian cell types and in agreement with previous observations (43), ribitol is not metabolized by S. cerevisiae cells.

Pathogenic (e.g. Candida albicans) and osmotolerant (e.g. Zygosaccharomyces rouxii) yeast species are known to produce high amounts of d-arabitol (44, 45). Based on studies using [2-14C]glucose, it was shown that C. albicans produces d-arabitol by dephosphorylating d-ribulose-5-P and then reducing d-ribulose by an NAD-dependent d-arabitol 2-dehydrogenase (d-ribulose reductase; Ard1) (46). The latter enzyme was also purified and characterized from Candida tropicalis (47). Many of the d-arabitol-producing yeast species are also able to utilize this pentitol as the sole carbon source (45). The d-arabitol utilization pathway most likely involves oxidation of arabitol to d-ribulose by d-arabitol 2-dehydrogenase and phosphorylation of d-ribulose to the pentose phosphate pathway intermediate d-ribulose-5-P by the homolog of the d-ribulokinase protein identified in this study. Ydr109c is indeed well conserved in Candida as well as in osmotolerant Zygosaccharomyces species. S. cerevisiae does not produce d-arabitol (44), and it is unlikely that d-ribulokinase participates in d-arabitol utilization in this species.

Why then, one may ask, has d-ribulokinase been conserved in species such as baker's yeast and higher eukaryotes, including humans? The most plausible endogenous precursor, in these species, for the d-ribulokinase substrate is certainly d-ribulose-5-P. Therefore, we propose that a possible physiological role of d-ribulokinase in species or cell types that do not produce significant amounts of free d-ribulose from pentitols or other pentose precursors may be to preserve the d-ribulose-5-P pool or to prevent potentially toxic accumulations of free d-ribulose by “re-phosphorylating” d-ribulose formed by nonspecific phosphatase activities from d-ribulose-5-P. As such, d-ribulokinase could be added to the growing list of so-called metabolite repair enzymes, i.e. enzymes that function to remove useless or sometimes toxic metabolites formed via side activities of metabolic enzymes (48, 49). In both S. cerevisiae and higher eukaryotes, low molecular weight phosphatases of the haloacid dehydrogenase protein superfamily may contribute to free ribulose formation from d-ribulose-5-P. Some of these phosphatases are quite promiscuous, and in S. cerevisiae, the poorly characterized Ykr070w and Ynl010w haloacid dehalogenase phosphatases have recently been shown to hydrolyze d-ribulose-5-P in addition to a range of other phosphomonoesters tested (50). In earlier studies, a partially purified acid phosphatase preparation, but not alkaline phosphatase preparation, from Z. rouxii was shown to display ribulose-5-P phosphatase activity (51). The existence of such phosphatase activities in mammals is supported by the presence of free ribulose in the urine of humans and fasted rats (52) and of elevated pentitol levels measured in patients with inborn errors in the pentose phosphate pathway. In humans, ribitol is usually present at very low levels in extracellular fluids (less than 6 μm in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (53)), but this pentitol as well as d-arabitol accumulate in patients with ribose-5-phosphate isomerase (53) or transaldolase (54) deficiencies. In a patient with ribose-5-phosphate isomerase deficiency, millimolar levels of ribitol and d-arabitol were measured in cerebrospinal fluid (53). In these disorders, the amounts of free pentoses formed via hydrolysis of phosphopentose precursors thus seem to exceed the capacity of ribokinase and the herein identified d-ribulokinase, leading to the reduction of excess pentoses and their accumulation as pentitols. FGGY silencing did not lead to detectable ribulose levels in the human cell lines used in this study when cultivated without ribitol supplementation. This may be explained by the only partial knockdown achieved by the shRNA method used and/or low ribulose-5-P phosphatase activity in those cell lines.

Alternatively, the simultaneous presence of d-ribulose-5-P phosphatase and d-ribulokinase activities in a eukaryotic cell could in principle contribute to fine-tuning the regulation of the pentose phosphate pathway flux by substrate cycling (55) between ribulose-5-P and ribulose. As opposed to the metabolite repair hypothesis, the participation of d-ribulokinase in metabolic flux regulation through substrate cycling would, however, call for the existence of a specific and (for example allosterically) regulated ribulose-5-P phosphatase activity rather than a nonspecific and non-regulated production of free ribulose by promiscuous phosphatases.

While this work was ongoing, a new enzymatic activity producing CDP-ribitol was identified in mammals by three independent groups (56–58). This activity is carried by the ISPD protein, which acts as a CDP-ribitol pyrophosphorylase using ribitol-5-P and CTP to form CDP-ribitol. Furthermore, CDP-ribitol was shown to be used by the transferases FKTN and FKRP to incorporate ribitol-5-P from CDP-ribitol into a phosphorylated O-mannosyl glycan (CoreM3) of the α-dystroglycan glycoprotein (57, 58). Abnormal glycosylation of α-dystroglycan, a receptor for matrix and synaptic proteins, can lead to congenital syndromes that are characterized by muscle, brain, and/or eye disorders (59, 60). Mutations in ISPD, FKTN, and FKRP had been known to cause dystroglycanopathies, but until these recent molecular identifications, their role in disease development had remained unknown. The metabolic pathway leading to the formation of ribitol-5-P, the substrate of ISPD, remains unknown. Some of the bacterial homologs of ISPD are fused to a reductase that converts d-ribulose-5-P to ribitol-5-P (61). Such an activity would allow to produce CDP-ribitol from the pentose phosphate pathway intermediate d-ribulose-5-P without the need of a sugar kinase. In the mammalian system, the results obtained by Gerin et al. (58) indicate that, at physiological levels of ribitol, the pathway leading to ribitol-5-P formation involves a sorbinil-sensitive aldose reductase and may indeed be independent of the FGGY protein studied here. However, at supraphysiological ribitol levels, the authors could show that FGGY silencing clearly leads to decreased CDP-ribitol formation in HEK293 cells. Under such conditions, FGGY is thus involved in CDP-ribitol formation, either by directly phosphorylating ribitol or by phosphorylating d-ribulose formed from ribitol. Our results show indeed that HEK293 cells can oxidize ribitol to d-ribulose and that the latter is a 35-fold better substrate for FGGY than ribitol in terms of catalytic efficiency. The observation that sorbinil does not inhibit CDP-ribitol formation in HEK293 cells cultivated in the presence of externally added ribitol favors, however, the hypothesis of a direct phosphorylation of ribitol by FGGY under these conditions. Interestingly, ribitol supplementation in cultivation medium or drinking water led to increased CDP-ribitol levels in mammalian cells and mice, respectively, and ribitol supplementation partially restored α-dystroglycan glycosylation in fibroblasts from patients with ISPD mutations (58). These observations suggest that in patients with mutations in ISPD, but also FKTN and FKRP, dietary ribitol supplementation could exert therapeutic effects via a pathway that depends on the ribitol and/or d-ribulose kinase activity of FGGY.

Experimental Procedures

Chemicals

Unless otherwise indicated, chemicals were from Sigma. All solvents used were HiPerSolv CHROMANORM LC-MS grade from VWR Scientific. Most of the analytical standards were either from Sigma, Carbosynth, or Roche Applied Science and when possible were of greater than 90% purity; LC-MS grade chemicals were used when available. Cell culture media and supplements as well as trypsin were purchased from Life Technologies, Inc. The yeast minimal medium Yeast Nitrogen Base (YNB) with ammonium sulfate and peptone were from MP Biomedicals. Hygromycin B was purchased from Cayman Chemical Co.

Microbial Strains, Cell Lines, and Plasmids

To reduce metabolic and physiological biases introduced by auxotrophic markers, prototrophic S. cerevisiae strains were used for the majority of yeast experiments shown in this study. To analyze the impact of two specific gene deletions on the metabolome, strains of the prototrophic deletion collection (MATa can1Δ::STE2pr-SpHIS5 his3Δ1 lyp1Δ0 ho−), created as described previously (62), in which the YDR109C and MPA43 genes were replaced by the KanMX cassette were used. Those ydr109cΔ::KanMX and mpa43Δ::KanMX knock-out strains are designated as ydr109cΔ and mpa43Δ strains throughout this article. As a wild-type control, we used an isogenic strain from the same deletion collection in which the non-functional HO allele was replaced by the KanMX cassette, except for co-cultivation experiments where an FY4 MATa prototrophic wild-type strain was used. For some experiments, auxotrophic BY4741 strains (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) without or with deletion of the YDR109C gene by replacement with the KanMX cassette were used (Euroscarf).

The BL21(DE3)pLysS E. coli cells used for recombinant protein expression were from Life Technologies, Inc. The stable HEK293 FGGY knockdown cell line and the corresponding control cell line were provided by Dr. Guido Bommer (58). The PH5CH8 cell line was provided by Dr. Nobuyuki Kato.

The Gateway plasmid pDONR221, used to create Entry clones with attL sites upstream and downstream of the gene of interest, was from Invitrogen. The Gateway plasmid pDEST527 was a gift from Dominic Esposito (Addgene plasmid 11518). The empty Gateway plasmid p41Hyg 1-F GW was a gift from Leonid Kruglyak and Sebastian Treusch (Addgene plasmid 58547) (63).

Construction of Plasmids for Recombinant Protein Expression and Rescue Experiments

To express the yeast YDR109C gene in a bacterial system, the coding sequence was PCR-amplified from prototrophic wild-type S. cerevisiae FY4 (MATa) genomic DNA using the YDR109cFwd and YDR109cRev primers (supplemental Table S5) and high fidelity Phusion DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primers were designed to contain attB sites, and the Gateway Cloning strategy (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was followed according to the manufacturer's instructions to clone the purified attB-flanked PCR product into the pDONR221 Entry vector, and to subsequently subclone the insert into the pDEST527 Destination vector. This resulted in the pDEST527-YDR109C expression plasmid allowing for IPTG-inducible production of N-terminally His6-tagged fusion protein in E. coli.