Abstract

Despite a long and successful history of citrate production in Aspergillus niger, the molecular mechanism of citrate accumulation is only partially understood. In this study, we used comparative genomics and transcriptome analysis of citrate-producing strains—namely, A. niger H915-1 (citrate titer: 157 g L−1), A1 (117 g L−1), and L2 (76 g L−1)—to gain a genome-wide view of the mechanism of citrate accumulation. Compared with A. niger A1 and L2, A. niger H915-1 contained 92 mutated genes, including a succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase in the γ-aminobutyric acid shunt pathway and an aconitase family protein involved in citrate synthesis. Furthermore, transcriptome analysis of A. niger H915-1 revealed that the transcription levels of 479 genes changed between the cell growth stage (6 h) and the citrate synthesis stage (12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h). In the glycolysis pathway, triosephosphate isomerase was up-regulated, whereas pyruvate kinase was down-regulated. Two cytosol ATP-citrate lyases, which take part in the cycle of citrate synthesis, were up-regulated, and may coordinate with the alternative oxidases in the alternative respiratory pathway for energy balance. Finally, deletion of the oxaloacetate acetylhydrolase gene in H915-1 eliminated oxalate formation but neither influence on pH decrease nor difference in citrate production were observed.

Aspergillus niger, a black aspergillus with “generally regarded as safe” status, is widely used in the biotechnological production of organic acids and industrial enzymes1. As a workhorse of organic acids, A. niger is a proficient producer of citrate, which is used extensively in the food and pharmaceutical industries owing to its safety, pleasant acidic taste, high water solubility, and chelating properties2.

If A. niger is to be used as a cell factory platform, its genetic background must be thoroughly understood. The available genome sequence of A. niger offers a new horizon for both scientific studies and biotechnological applications3. A. niger strains NRRL 3 and ATCC 1015, which can synthesize citrate, have undergone genome-wide analysis1,3, and a complete genome-scale metabolic model with genomic annotation has been constructed based on the genome sequence of A. niger ATCC 10154. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism of citrate accumulation remains only partially understood5,6. For example, 5 citrate synthases have been identified in ATCC 90297; however, the primary gene and the timing of the activity of each enzyme during fermentation remain a mystery. Furthermore, the citrate transporter remains unknown even though the transport process is critical in the production of citrate. In addition, the role of alternative oxidases for energy balance during citrate production must be clarified8.

In this study, the genomes of three A. niger strains with different citrate production efficiencies were sequenced, among which the genome of industrial strain A. niger H915-1 was sequenced with third-generation sequencing, which provides much longer reads and unbiased genome coverage compared with those of second-generation sequencing. Moreover, transcriptome analysis during citrate fermentation by A. niger H915-1 was conducted to explore how the regulation of enzyme expression facilitates citrate accumulation. Finally, the oxaloacetate acetylhydrolase gene (oah) was deleted in A. niger H915-1 to exam the role of oxalate on pH decrease and citrate production. The results of this study deepen the understanding of citrate accumulation by A. niger and provide potential engineering targets for further improvement in citrate production.

Materials and Methods

Strains

A. niger strains H915-1, L2, and A1 were provided by Jiangsu Guoxin Union Energy Co., Ltd (Yixing, Jiangsu Province, China), the third citrate producer in China. Strain H915-1 is an industrial producer, which was generated through several round of compound mutation, whereas strains L2 and A1 are the degenerated isolates of A. niger H915-1 during subsequent culture, as filamentous fungi frequently and spontaneously degenerate during maintenance in artificial media due to chromosome instability9. Escherichia coli JM109 was used as a host for recombinant DNA manipulation.

Citrate fermentation by A. niger in 50-mL flasks

For citrate fermentation, conidia were inoculated in seed culture broth (a mixture of corn steep liquor and corn starch with a total sugar content of 10% and total nitrogen content of 0.2%). Eighty milliliters of seed culture was placed in 500-mL flasks and mixed at 250 rpm and 35 °C for 24 h. With 10% inoculum, the fermentation was performed in culture medium (a mixture of corn steep liquor and corn starch with a total sugar content of 16% and total nitrogen content of 0.08%) at 250 rpm and 35 °C until the reducing sugar was exhausted.

Fed-batch cultivations of citrate by A. niger H915-1 in a 3-L fermenter

Batch cultivations were performed in 3-L fermenters with a working volume of 1.5 L, and the temperature was maintained at 35 °C. For inoculation of the bioreactor, the stirring rate was adjusted to 900 rpm and aeration was set at 3.5 volumes of air per volume of fluid per minute (vvm).

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis

For quantification of extracellular metabolites, a culture sample was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was immediately filtered through a filter with a 0.45-μm pore size. The filtrate was kept at −20 °C until for analysis. Citrate and oxalate concentration was detected and quantified with ultraviolet light at 210 nm by using an Amethyst C18-H column (250 × 4.6 mm; Sepax Technologies, Newark, DE, USA). Elution was carried out at 30 °C with 0.01% H3PO4 at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min.

Reducing sugar assay

Reducing sugar was detected with the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid reducing sugar method10.

Biomass determination

Five milliliter of sample was filtrated through Miracloth (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) to collect the hyphae and washed with distilled water. The hyphae in miracloth was heated at 105 °C until the weight did not change. For calculation of dry cell weight (DCW), the weight of Miracloth was measured previously and deducted from the total weight to generate net weight, then the net weight per unit volume was calculated as DCW.

A. niger cultivation and DNA preparation for genome sequencing and annotation

Conidia (1 × 106) were cultivated in 100 mL malt extract liquid medium (3% malt extract and 0.5% tryptone) for 2 days at 35 °C. The mycelia were harvested with Miracloth and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The genome DNA of A. niger was isolated with a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA) and subjected to quality control and library construction for genome sequencing.

Next-generation sequencing and genome assembly

Genome sequencing of A. niger H915-1, L2, and A1 was performed with an Illumina Miseq 2000 system using paired-end libraries. After clean data were obtained, reads of A. niger A1 were assembled by using the Celera Assembler with the optimal linear combination algorithm11. The sequence data for A. niger A1 were deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number LMYC00000000.

Third-generation sequencing and genome assembly

Genome sequencing of A. niger H915-1 and L2 were performed by using a PacBio RS II system with a 20-kb library. Sequences were de novo assembled with the hierarchical genome assembly process12. The longest sequencing reads were selected as a seeding sequence data set, according to which, as a reference, shorter reads were recruited and preassembled by using basic local alignment with successive refinement13. These preassembled reads were assembled by using the Celera Assembler with the optimal linear combination algorithm11. Then, the assembly was refined by using initial read data, and accuracy was improved by using Quiver12. Subsequently, minimus2 was used to connect the contigs and generate the final consensus that represented the genome14. Finally, the sequences generated by next-generation sequencing were mapped to the assembled genome for error correction by using BWA. Sequence data for A. niger H915-1 and L2 were deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession numbers LLBX00000000 and LKBF00000000, respectively.

Gene prediction and annotation

Several gene-finding software programs were used for predicting genes. AUGUSTUS15, SNAP16, and GeneMark + ES17 were used for ab initio prediction, and Genewise18 was used for homology prediction. Subsequently, EVidenceModeler was used to incorporate all of the predicted results to generate final general feature format file19.

Protein sequences of all predicted genes were mapped to a non-redundant protein database (nr, National Center for Biotechnology Information), SWISS-PROT, and the TREMBLE database by using BLASTP with an E-value of 1e-5. Gene ontology (GO) annotation was performed by using interproscan-5.4-47.0 to blast to quick GO from the Interpro database. The amino acid sequences of all predicted genes were mapped to the Eukaryotic Orthologous Group and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes databases by using BLASTP with an E-value of 1e-5.

Prediction of transfer RNA (tRNA) was carried out by using tRNAscan-SE 1.23, which combines several detection programs and analysis models20. Annotation of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was finished by using RNAmmer 1.2 with hidden Markov models21.

Repeat element analysis

Repetitive sequences were detected according to Repbase by RepeatMasker by using the default parameters22. Then, RepeatProteinMask was executed to search against the transposable element protein database to identify repeat related proteins. In addition, the tandem repeats were annotated with using the Tandem Repeats Finder program.

Prediction of ortholog group

Blastp was first used to generate the pairwise protein sequence with similarity of E-value less than 1e-5. Secondly, OrthoMCL was used to cluster similar genes by setting main inflation value 1.5 and other default parameters23.

Variants analysis

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions and deletions (indels) were detected by using SAMtools and comparing the genomes of A. niger L2 and A1 to A. niger H915-1. Then, SnpEff was used to annotate the effects of the variants24. Structural variation (SV) was detected by using Pindel.

RNA extraction and purification for RNA-seq

Mycelia were frozen and ground under liquid nitrogen by using a mortar and pestle. RNA was isolated with an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and checked for RNA integrity by using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, US). Qualified total RNA was further purified successively with an RNeasy micro kit (QIAGEN) and RNase-Free DNase Set (QIAGEN).

Complementary DNA (cDNA) library preparation and sequencing

Purified total RNA was digested to eliminate rRNA. The RNA was then fragmented by heating at 94 °C and used to synthesize cDNA. The double-stranded cDNA was adenylated at the 3′ end, then ligated to the sequencing adapters. Pair-end sequencing was performed by using Illumina HiSeq 2500 according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Analysis of Illumina transcriptome sequencing results

Raw data were filtered to remove low-quality sequences by using FASTX (version 0.0.13; http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/index.html) to generate clean data. Clean reads were mapped to the genome of A. niger H915-1 as a reference by using TopHat (version 2.0.9)25 according to the spliced mapping algorithm. The Cufflinks program (version 2.1.1)26 was used to calculate unigene expression with the using FPKM method (Fragments per kb per million reads). Gene expression differences among the samples were analyzed by using Cufflinks (version 2.1.1) with a false discovery rate of ≤0.05 and a fold change of ≥2. A Perl script was used to assign a functional class to each unigene and establish pathway associations between unigenes and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database. The sequence data have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database under the GEO accession number GSE74544.

Real-time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

For verification of transcriptome data, qPCR was performed by LightCycler 480 system (Roche, Germany) with 2 × SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Dalian, China). The primers were designed by Beacon Designer 7 and the sequences were listed in Supplementary Table S1.

As the major genes of central metabolism were identified by transcriptome, these genes’ expression levels of H915-1 at 48 h and A1 at 60 h were compared. The primers used were also listed in Supplementary Table S1.

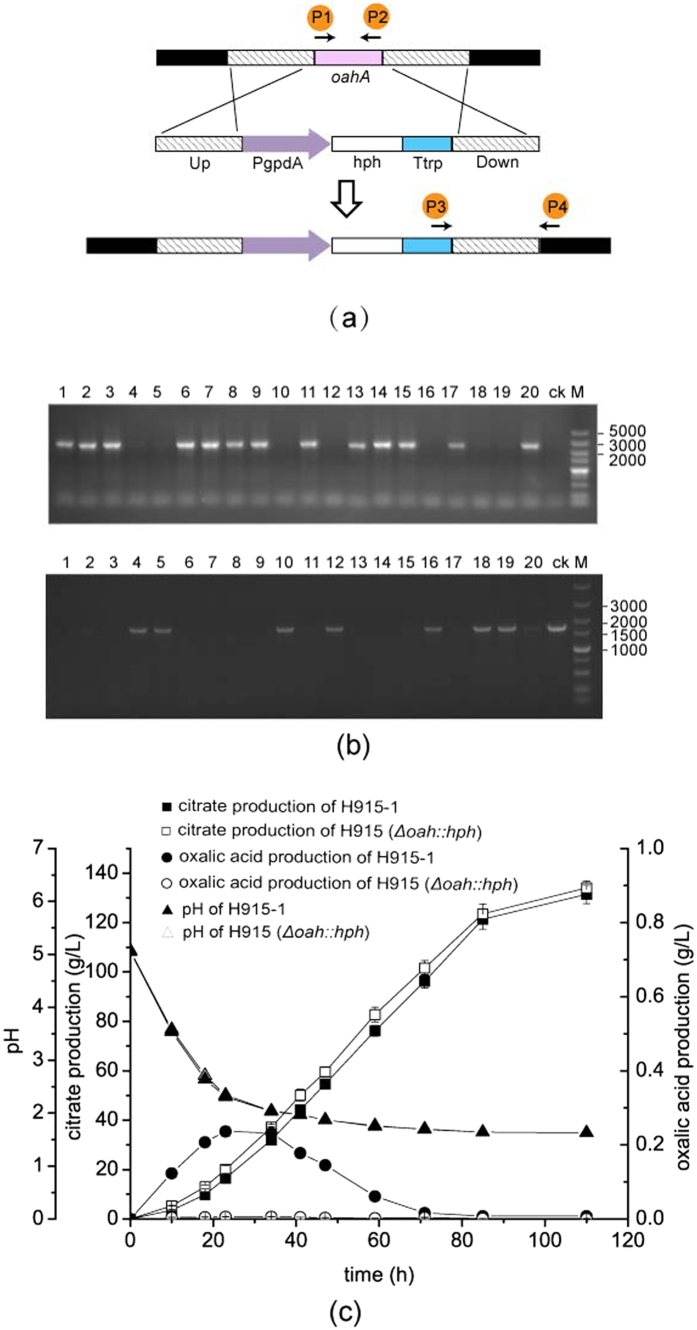

Construction of the gene-knockout cassette for oah

The 2.3-kb sequence upstream of oah, called oahA5, was cloned by using primers (Supplementary Table S1) of oahA5-F and oahA5-R and the genome of A. niger H915-1 as a template. The 2.3-kb sequence downstream of oah, called oahA3, was cloned using primers of oahA3-F and oahA3-R. The sequence oahA3 was digested with Spe I and Hin dIII and subsequently ligated to pAN7-1 (GenBank accession no. Z32698) and digested with Xba I and Hin dIII to construct plasmid pAN-oah3. pAN-oah3 was digested with Xho I and Xba I, ligated to the plasmid pSZH-XynB27, and digested with Xho I and Nde I to construct the plasmid pSZH-oah3. pSZH-oah3 was digested with Xba I and Xho I, ligated to oahA5, and digested with Xba I and Sal I to construct the plasmid pSZH-oahA. The gene-knockout cassette of oah was obtained through PCR with primer oahA5-F and oahA3-R by using pSZH-oahA as a template. The primers used to validate the recombinant genome were P1, P2, P3, and P4 (Supplementary Table S1).

Transformation of A. niger

Protoplast formation and transformation was performed based on a method published by Blumhoff et al.28. Conidia (1 × 108) were cultivated in 100 mL malt extract medium for 11 h at 35 °C. The mycelium was harvested via filtration through Miracloth (Calbiochem) and washed with deionized water. Protoplastation was achieved in the presence of 5 g L−1 lysing enzymes from Trichoderma harzianum (Sigma. Saint Louis, MO, USA), 0.075 U mL−1 chitinase from Streptomyces griseus (Sigma), and 460 U mL−1 glucuronidase from Helix pomatia (Sigma) in KMC (0.7 M KCl, 50 mM CaCl2, 20 mM Mes/NaOH, pH 5.8) for 2 h at 37 °C and 120 rpm. Protoplastation was monitored every 30 min with a microscope. The protoplasts were filtered through Miracloth and collected via centrifugation at 2,000 × g and 4 °C for 10 min. The protoplasts were washed with cold STC (1.2 M sorbitol, 10 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5) and subsequently resuspended in 100 μL STC and directly used for transformation. Ten micrograms of linear knock-out cassette was mixed with 100 μL STC solution containing at least 107 protoplasts and 330 μL freshly prepared polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution (25% PEG 6000, 50 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5) and kept on ice for 20 min. After mixing with an additional 2 mL PEG solution and incubating at room temperature for 10 min, the protoplast mixture was diluted with 4 mL STC. The aliquots were mixed with 4 mL liquid top agar warmed to 50 °C, spread on bottom agar containing 180 μg mL−1 hygromycin, and incubated at 35 °C for 3–6 days. All transformants were purified three times via single-colony isolation on the selection medium. The correct integration was verified with PCR analysis by using specific genomic primers. The fermentation was performed for 3 times and the data of production and yield were analyzed for the statistical significance of differences by Tukey’s honestly significant difference text (T-text) using a standard package (SPSS for Windows, Version 17; SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA).

Results and Discussion

Citrate production by A. niger H915-1, L2, and A1

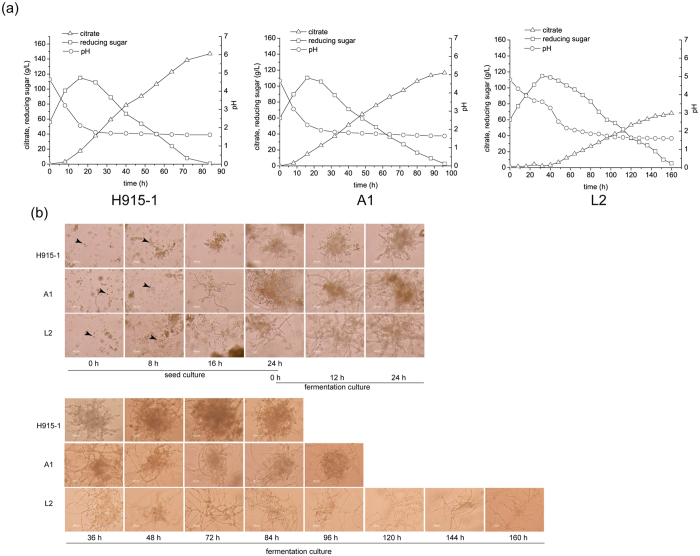

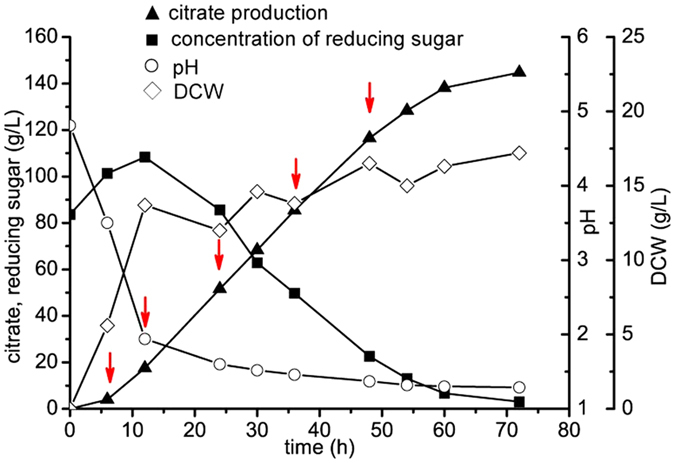

Among A. niger strains with different citrate production efficiencies, A. niger H915-1 produced the highest citrate titer of 157 g L−1 in 85 h, whereas A. niger A1 produced 117 g L−1 in 92 h and A. niger L2 produced 76 g L−1 in 160 h (Fig. 1a). We found that during citrate fermentation, the mycelia of different strains aggregated in various forms (Fig. 1b), which indicated that citrate production was influenced by the morphology of the microcolonies6. A. niger H915-1 formed bulbous hyphae with short, swollen hyphal branches, whereas A. niger A1 formed less compact pellets with less hyphal branching and longer mycelia, and A. niger L2 formed mycelial clumps. These differences in morphology may influence the viscosity of the medium and further affect hyphal respiration29. The tight pellet form facilitated citrate formation, and the diffused filamentous form reduced citrate production and productivity. In addition, aeration rate was an important parameter for citrate production. When aeration was maintained at 3.5 vvm, the citrate production of A. niger H915-1 reached 145 g L−1 in 72 h (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Citrate fermentation of different A. niger strains.

(a) Citrate titer and fermentation time. Δ, citrate production. □, concentration of reducing sugar. ○, pH. (b) Morphology of different strains. Bar represents 40 μm. Black arrow pointed to a conidium.

Figure 2. Fed-batch culture of A. niger H915-1 for citrate production.

Aeration was maintained at 3.5 vvm. Sample time was shown in red arrows. ▲, citrate production. ■, concentration of reducing sugar. ○, pH. ◊, DCW.

General genome statistics and differences among the three strains

Three A. niger strains (H915-1, A1, and L2) capable of gradient citrate production were selected for genome sequencing. The genome sequences of A. niger H915-1 and L2 were obtained with a PacBio RS II system, and A. niger A1 was sequenced by using whole-genome shotgun paired-end sequencing. Sequences of A. niger H915-1 and L2 were further improved to high-quality assemblies of 30 finished contigs (Table 1). The assembled genome of A. niger A1 consisted of 319 contigs. The genome sizes of A. niger H915-1, L2, and A1 were 35.98 Mb, 36.45 Mb, and 34.64 Mb, respectively, and the number of predicted genes ranged from 10,123 to 10,433—approximately 26% smaller than A. niger CBS 513.88 and 10% smaller than A. niger SH2, both of which are enzyme production strains. The number of tRNA in A. niger H915-1 and L2 were more than 2-fold those of A. niger A1, CBS 513.88, and SH2. To investigate the reason of dramatic changes on tRNA number, the genome of H915-1 was assembled either de novo or using LLBX00000000 as reference only with the “next-generation” sequencing data. The de novo assembly genome was 35.5 M with 255 tRNA, and the genome assembled using LLBX00000000 as reference was 36.0 M with 667 tRNA, indicating that the problem of losing information by second-generation sequencing was not significant, but the assembly method influenced the genome result a lot and also the “next-generation” sequencing with different read lengths was importance for rectify assembly results30,31. The ortholog names was provided in Supplementary Table S2 for matching gene ID of H915-1 to gene ID of CBS513.88.

Table 1. General features of genomes of A. niger H915-1, L2 and A1.

| A. niger H915 | A. niger L2 | A. niger A1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (Mb) | 35.98 | 36.45 | 34.64 |

| Contigs | 30 | 30 | 319 |

| N50 (bp) | 4,441,427 | 4,157,665 | 247,692 |

| Sequencing depth | 88.05 | 88.07 | 83 |

| Gene models | 10,318 | 10,433 | 10123 |

| Protein length (amino acids) | 498 | 501 | 498 |

| Exons per gene | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Average gene length (bp) | 1,787 | 1,781 | 1,756 |

| Number of tRNA | 666 | 557 | 278 |

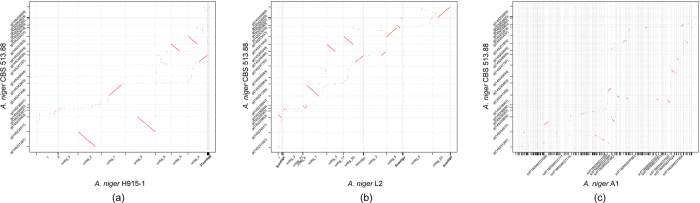

The Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) is a database where the orthologous gene products were classified. We searched the annotated sequences for the genes involved in COG classifications and more than 3,700 sequences had a COG classification. Compared with strain L2 and A1, there are more genes belonging to categories A (RNA processing and modification), C (Energy production and conversion), F (Nucleotide transport and metabolism), G (Carbohydrate transport and metabolism) and S (Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport) in strain H915-1 (Supplementary Table S3). The three strains shared 9097 gene groups (Supplementary Figure S1). Compared with A. niger L2 and A1, A. niger H915-1 contained only 1 unique gene group and lacked 58 groups of genes (Supplementary Table S4). Syntenic dot plot analysis of the three experimental strains and A. niger CBS 513.88 (Fig. 3) and extensive structural reorganizations were observed. When compared to genome of H915-1 as reference, the genome of L2 and A1 contained 1210 SNP/indel and 52 SVs, within which existed 57 non-synonymous SNPs (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6) and 35 SVs involving gene mutation (Supplementary Table S7).

Figure 3. Syntenic dot plot of A. niger H915, A. niger L2 and A. niger A1 with A. niger CBS 513.88.

(a) A. niger H915. (b) A. niger L2. (c) A. niger A1.

For the genes mutated in strains of A1 and L2, the most notable was a succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase involved in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) shunt pathway for succinate supplement in TCA cycle, indicating that metabolite flux was modulated for citrate production. Also, a mutation was found in an aconitase family protein, which could relate to the production of citrate. Furthermore, mutations of a proline utilization trans-activator and a branched-chain-amino-acid aminotransferase indicated amino acid metabolism may relate to citrate synthesis. The synthesis of amino acids were started from organic acids in glycolysis and TCA cycle. Pyruvate, 3-phospho-D-glycerate, oxaloacetate and 2-oxoglutarate were all precursors of amino acids, as a result, amino acids synthesis pathway could drain metabolites used in organic acids synthesis. In addition, SVs were found in 60S ribosomal protein L5 relevant for mediating 5S rRNA binding32, DNA repair protein, DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit, RNA-splicing protein and mRNA transport regulator, suggesting changes on cell viability. As citrate is a primary metabolite for A. niger, the production of citrate may associate with the vegetative growth rate.

For citrate fermentation of A. niger, the morphological development was considered to start with the aggregation of conidia right after inoculation, then the conidia begun to germinate and formed mycelium33,34. The pathways for formation of hydrophobin and melanin (Supplementary Table S8), which induced conidia aggregation and subsequent germ tube aggregation34,35,36 had no differences, though the 3 strains showed different morphology of micro-colonies. Fungal cell wall consists of 80–90% polysaccharides, and most of the remainders are protein and lipid37. The functions of these diverse cell wall proteins included defense response38, maintaining cell surface hydrophobicity39, and regulation of morphogenesis40. The cell wall protein lrx1 mutated Arabidopsis thaliana developed swell and branch root hairs40. In this study, a cell wall protein lacked in H915-1, and there existed the possibility to influence the cell morphology.

Transcriptome analysis of H915-1 during citrate production

To obtain a general picture of A. niger cell physiology during citrate production, we studied the transcriptome of H915-1 during this process in a 3-L fermenter. In the case that aeration was maintained at 3.5 vvm, hyphae were sampled at 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h and 48 h. When fermented for 6 h, the medium pH dropped from 4.8 to 3.5, and the hyphae were still at growing age and citrate productivity was slow at 0.66 g L−1 h−1. Subsequently, citrate productivity increased to 2.34 g L−1 h−1, 3.26 g L−1 h−1, 2.75 g L−1 h−1, and 1.94 g L−1 h−1 at 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h, respectively (Fig. 2).

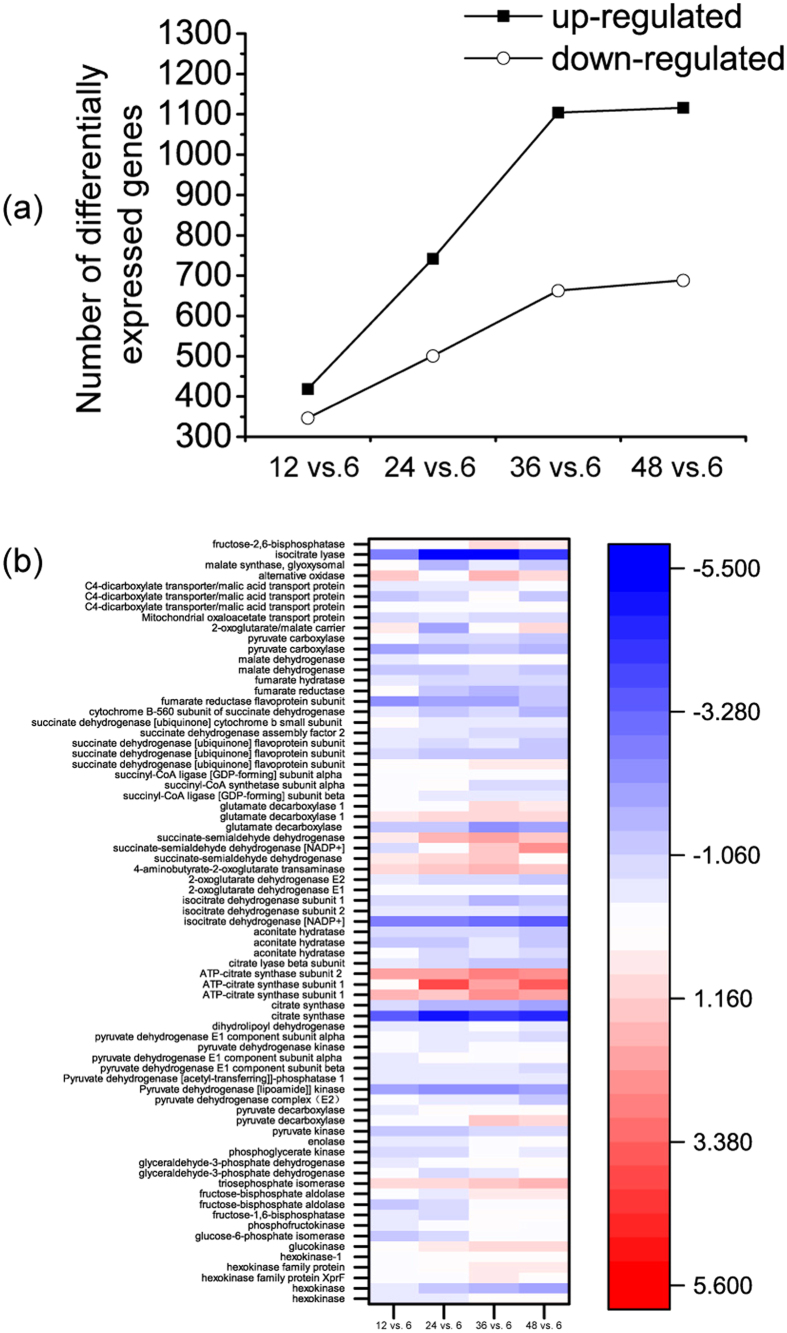

Compared with expression at the cell growth stage (6 h), the expression of 479 of 9953 genes changed at all 4 time points during the citrate synthesis stage (12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h): 269 genes showed increased expression levels, and 210 genes were down-regulated (fold change ≥ 2 and false discovery rate ≤ 0.05). These results identified the key genes for citrate production. In addition, the number of differentially expressed genes increased with fermentation time (Fig. 4a), which indicated a strong cellular response to the changing conditions of citrate secretion.

Figure 4. Transcriptional profile during citrate fermentation.

(a) Number of differentially expressed genes during fermentation. (b) Expression profile of genes in glycolysis and TCA cycle.

For verification of the transcriptome data, the fermentation was repeated and sampled at the same time as that for transcriptome analysis. Several genes including genes in central metabolism and 2 other genes (evm.model.1.1208 and evm.model.unitig_3.181), which increased greatly during fermentation, were analyzed by qPCR and the fold change of gene expression level was compared with that of the transcriptome data (Supplementary Figure 2). The result showed similar trend by qPCR and transcriptome analysis. The expression level of evm.model.1.1208 and evm.model.unitig_3.181 all increased by similar folds at 12, 24, 36 and 48 h compared to 6 h in both experiments, and the expression level of genes in central metabolism were also up-regulated/down-regulated at similar levels in both experiments, confirming the result of transcriptome analysis.

Regulation of central metabolism (glycolysis, TCA cycle, rTCA cycle and GABA shunt pathway) for citrate production

Citrate is formed mainly via cytosolic glycolysis and the subsequent mitochondrial TCA cycle. The expression levels of genes involved in glycolysis were mostly unaffected, but many genes involved in the TCA cycle were down-regulated (Fig. 4b, Table 2). Six isoenzymes catalyze glucose phosphorylation in A. niger H915-1. Of these, 5 isoenzymes are hexokinases, the transcription levels of which did not change noticeably. Hexokinase activity was non-competitively inhibited by citrate41, and to compensate for metabolite flux, the expression level of glucokinase was up-regulated gradually during citrate production (Fig. 5a).

Table 2. Transcription levels of genes involving glucose metabolism during citrate fermentation.

| EC number | gene ID | Gene function | FPKM-6h | FPKM-12h | FPKM-24h | FPKM-36h | FPKM-48h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| glycolysis | |||||||

| EC 2.7.1.1 | evm.model.unitig_0.782 | hexokinase | 335.407 | 263.428 | 264.615 | 398.452 | 396.328 |

| EC 2.7.1.1 | evm.model.unitig_1.1360 | hexokinase | 0.799634 | 0.518701 | 0.376546 | 0.25131 | 0.219428 |

| EC 2.7.1.1 | evm.model.unitig_2.1160 | hexokinase family protein XprF | 12.973 | 13.2989 | 12.8881 | 18.8512 | 14.8755 |

| EC 2.7.1.1 | evm.model.unitig_4.158 | hexokinase family protein | 49.2115 | 49.5622 | 61.4378 | 65.9747 | 75.2536 |

| EC 2.7.1.1 | evm.model.unitig_6.819 | hexokinase-1 | 19.7688 | 20.2945 | 25.5583 | 24.9562 | 25.509 |

| EC 2.7.1.2 | evm.model.unitig_4.1015 | glucokinase | 127.778 | 150.188 | 203.7 | 242.765 | 250.044 |

| EC 5.4.2.2 | evm.model.unitig_0.1273 | phosphoglucomutase | 92.2402 | 108.093 | 119.862 | 216.005 | 192.424 |

| EC 5.4.2.2 | evm.model.unitig_0.474 | phosphoglucomutase | 45.8516 | 54.1326 | 57.7454 | 77.0618 | 68.9388 |

| EC 5.3.1.9 | evm.model.unitig_6.538 | glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 185.76 | 83.2219 | 101.433 | 153.62 | 149.017 |

| EC 2.7.1.11 | evm.model.unitig_1.93 | phosphofructokinase | 332.854 | 231.523 | 273.895 | 381.057 | 321.602 |

| EC 3.1.3.11 | evm.model.1.362 | fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase | 185.489 | 126.953 | 103.246 | 196.543 | 215.136 |

| EC 4.1.2.13 | evm.model.unitig_0.1289 | fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 1415.9 | 608.32 | 742.795 | 1381.51 | 1233.53 |

| EC 4.1.2.13 | evm.model.unitig_5.221 | fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 4.14539 | 3.74066 | 2.58741 | 7.12841 | 6.59831 |

| EC 5.3.1.1 | evm.model.unitig_5.192 | triosephosphate isomerase | 781.339 | 500.828 | 658.134 | 1048.47 | 1070.47 |

| EC 5.3.1.1 | evm.model.unitig_0.1612 | triosephosphate isomerase | 99.5623 | 205.847 | 190.824 | 264.163 | 351.897 |

| EC 1.2.1.12 | evm.model.unitig_4.875 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 289.264 | 257.795 | 158.841 | 222.297 | 289.137 |

| EC 1.2.1.12 | evm.model.unitig_6.799 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 2149.06 | 1463.62 | 1729.79 | 2551.67 | 2242.18 |

| EC 2.7.2.3 | evm.model.unitig_1.643 | phosphoglycerate kinase | 1092.79 | 558.191 | 673.403 | 922.674 | 866.895 |

| EC 5.4.2.1 | evm.model.unitig_6.503 | phosphoglycerate mutase | 95.5362 | 36.1718 | 64.161 | 84.4621 | 65.0384 |

| EC 5.4.2.1 | evm.model.unitig_6.710 | phosphoglycerate mutase | 769.017 | 423.86 | 524.205 | 666.103 | 634.037 |

| EC 4.2.1.11 | evm.model.unitig_6.540 | enolase | 60.0857 | 45.7904 | 43.6861 | 57.3401 | 76.4556 |

| EC 4.2.1.11 | evm.model.unitig_1.422 | enolase | 1916.1 | 1019.34 | 1313.81 | 1840.59 | 1892.42 |

| EC 2.7.1.40 | evm.model.unitig_0.620 | pyruvate kinase | 1765.16 | 838.18 | 840.933 | 959.252 | 922.378 |

| tricarboxylic acid cycle | |||||||

| EC 2.3.1.12 | evm.model.unitig_0.153* | dihydrolipoyllysine-residue acetyltransferase | 496.018 | 402.791 | 346.071 | 317.373 | 227.624 |

| EC 1.2.4.1 | evm.model.unitig_0.667* | pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit alpha | 297.87 | 261.578 | 236.515 | 237.141 | 162.256 |

| EC 1.2.4.1 | evm.model.unitig_2.1112* | pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta | 219.671 | 169.985 | 139.605 | 155.358 | 124.71 |

| EC 1.2.4.1 | evm.model.unitig_3.851 | pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit alpha | 13.0844 | 9.68933 | 14.6326 | 11.1757 | 15.6863 |

| EC 1.8.1.4 | evm.model.unitig_0.477* | dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase | 137.583 | 104.234 | 95.4635 | 111.925 | 88.9546 |

| EC 2.3.3.1 | evm.model.unitig_4.422* | citrate synthase | 887.236 | 277.72 | 153.559 | 146.579 | 146.101 |

| EC 2.3.3.1 | evm.model.unitig_5.597* | citrate synthase | 1783.01 | 918.481 | 542.466 | 513.1 | 486.779 |

| EC 2.3.3.1 | evm.model.unitig_1.1397 | citrate synthase | 166.357 | 13.8929 | 5.34897 | 9.72465 | 6.61541 |

| EC 2.3.3.1 | evm.model.unitig_5.827 | citrate synthase | 55.1809 | 8.74314 | 38.5607 | 12.3544 | 26.6205 |

| EC 2.3.3.1 | evm.model.unitig_2.384 | citrate synthase | 2.52289 | 3.07562 | 36.8849 | 10.2526 | 29.7107 |

| EC 2.3.3.8 | evm.model.unitig_3.1144 | ATP-citrate synthase subunit 2 | 17.2562 | 71.315 | 67.7677 | 118.432 | 94.7237 |

| EC 2.3.3.8 | evm.model.unitig_3.1145 | ATP-citrate synthase subunit 1 | 28.8278 | 94.1346 | 80.0228 | 159.645 | 118.98 |

| EC 4.1.3.6 | evm.model.unitig_2.489* | citrate lyase beta subunit | 36.8118 | 26.2511 | 17.9149 | 15.3349 | 14.9401 |

| EC 4.2.1.3 | evm.model.unitig_1.1226* | aconitate hydratase | 896.845 | 720.406 | 447.551 | 601.52 | 551.053 |

| EC 4.2.1.3 | evm.model.unitig_5.803* | aconitate hydratase | 69.8504 | 41.158 | 39.9385 | 40.9545 | 29.8112 |

| EC 4.2.1.3 | evm.model.unitig_0.1022 | aconitase | 0.05719 | 0 | 0.219753 | 0.054301 | 0 |

| EC 4.2.1.3 | evm.model.unitig_6.517 | aconitate hydratase | 3.2308 | 1.44962 | 1.23429 | 2.01631 | 1.53043 |

| EC 1.1.1.41 | evm.model.unitig_1.461* | isocitrate dehydrogenase (NAD+) subunit 1 | 651.892 | 397.868 | 316.08 | 238.206 | 261.487 |

| EC 1.1.1.41 | evm.model.unitig_1.881* | isocitrate dehydrogenase (NAD+) subunit 2 | 117.139 | 91.5155 | 77.0455 | 74.0661 | 66.8811 |

| EC 1.1.1.42 | evm.model.unitig_0.935 | isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP+) | 379.561 | 55.4311 | 53.793 | 43.56 | 36.8787 |

| EC 1.2.4.2 | evm.model.1.395* | 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 | 123.4 | 101.134 | 68.2161 | 101.575 | 82.1217 |

| EC 1.2.4.2 | evm.model.unitig_1.1359* | 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase | 0.175744 | 0 | 0.082844 | 0 | 0.146153 |

| EC 2.3.1.61 | evm.model.unitig_3.373* | dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyltransferase | 906.116 | 585.033 | 461.624 | 440.09 | 430.991 |

| EC 1.8.1.4 | evm.model.unitig_0.477* | dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase | 137.583 | 104.234 | 95.4635 | 111.925 | 88.9546 |

| EC 6.2.1.4 | evm.model.unitig_1.691* | Succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit alpha | 10.1584 | 8.35142 | 10.9483 | 6.28717 | 6.26733 |

| EC 6.2.1.4 | evm.model.unitig_6.212* | succinyl-CoA ligase (GDP-forming) subunit alpha | 167.72 | 151.294 | 152.653 | 134.668 | 143.569 |

| EC 6.2.1.5 | evm.model.unitig_5.547* | succinyl-CoA ligase (GDP-forming) subunit beta | 187.764 | 164.558 | 147.869 | 139.546 | 136.451 |

| EC 1.3.5.1 | evm.model.unitig_0.1278* | succinate dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein subunit | 24.5134 | 26.5336 | 25.821 | 34.938 | 34.3454 |

| EC 1.3.5.1 | evm.model.unitig_5.222* | succinate dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein subunit | 106.025 | 80.5352 | 64.0832 | 82.0902 | 49.7971 |

| EC 1.3.5.1 | evm.model.unitig_0.912* | succinate dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein subunit | 300.998 | 183.431 | 129.831 | 141.769 | 117.838 |

| EC 4.2.1.2 | evm.model.unitig_4.976* | fumarate hydratase | 216.899 | 165.403 | 133.22 | 129.303 | 125.578 |

| malate supplementary pathway | |||||||

| EC 1.1.1.37 | evm.model.unitig_0.152* | malate dehydrogenase | 382.681 | 178.625 | 166.671 | 194.694 | 144.212 |

| EC 1.1.1.37 | evm.model.unitig_4.581 | malate dehydrogenase | 1180.59 | 937.119 | 1049.38 | 1328.52 | 1438 |

| EC 1.1.1.37 | evm.model.unitig_3.674 | malate dehydrogenase | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EC 1.1.1.37 | evm.model.unitig_0.1439 | malate dehydrogenase | 0 | 0.733162 | 0.69599 | 1.80872 | 1.30924 |

| EC 6.4.1.1 | evm.model.1.596 | pyruvate carboxylase | 1072.72 | 247.724 | 344.37 | 407.141 | 385.564 |

| EC 6.4.1.1 | evm.model.unitig_4.358* | pyruvate carboxylase | 3.10673 | 2.89939 | 1.60237 | 1.91294 | 1.46637 |

| Alternative aeration | |||||||

| EC 1.6.5.9 | evm.model.unitig_1.793 | alternative NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase | 22.4626 | 16.162 | 23.7158 | 14.4778 | 12.7033 |

| evm.model.unitig_3.600 | alternative oxidase | 0 | 0.287791 | 0 | 0.27723 | 0.237374 | |

| evm.model.unitig_3.832 | alternative oxidase | 29.5249 | 76.824 | 27.4381 | 99.4477 | 54.1134 | |

| Glyoxylate cycle | |||||||

| EC 2.3.3.9 | evm.model.unitig_4.427 | malate synthase, glyoxysomal | 144.411 | 152.274 | 43.8047 | 93.8427 | 68.3562 |

| EC 4.1.3.1 | evm.model.unitig_2.434 | isocitrate lyase | 1912.74 | 277.935 | 41.5601 | 47.8565 | 114.906 |

| EC 4.1.3.1 | evm.model.unitig_4.958* | isocitrate lyase | 450.798 | 136.445 | 121.203 | 118.647 | 160.556 |

| GABA shunt pathway | |||||||

| EC 2.6.1.19 | evm.model.unitig_6.167* | 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase | 44.1905 | 92.7175 | 120.197 | 163.909 | 105.917 |

| EC 1.2.1.16 | evm.model.1.554 | succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (NADP+) | 32.9799 | 39.6433 | 41.2847 | 62.5501 | 43.2657 |

| EC 1.2.1.16 | evm.model.unitig_2.1270 | Succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (NAD(P)+) | 18.7586 | 31.3531 | 37.5994 | 46.1063 | 23.1694 |

| EC 1.2.1.16 | evm.model.unitig_4.289 | aldehyde dehydrogenase family protein | 38.071 | 48.0361 | 28.8966 | 40.7511 | 50.4369 |

| EC 1.2.1.16 | evm.model.unitig_5.338 | succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (NADP) | 19.1193 | 9.30071 | 18.9276 | 47.9931 | 107.202 |

| EC 1.2.1.16 | evm.model.unitig_5.445 | Succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (NAD(P)+) | 4.14887 | 7.1628 | 15.265 | 16.603 | 9.76361 |

| EC 1.2.1.16 | evm.model.unitig_6.87 | Glutarate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 18.0798 | 36.4844 | 40.734 | 41.9151 | 61.8611 |

| EC 4.1.1.15 | evm.model.unitig_0.1336 | glutamate decarboxylase | 19.2535 | 8.99677 | 7.21094 | 3.60937 | 5.17597 |

| EC 4.1.1.15 | evm.model.unitig_1.1110 | glutamate decarboxylase 1 | 2129.58 | 2923.29 | 3713.03 | 3881.53 | 4501.63 |

| EC 4.1.1.15 | evm.model.unitig_4.236* | glutamate decarboxylase 1 | 2.6946 | 2.51931 | 2.15859 | 5.39455 | 3.62821 |

| EC 1.4.1.4 | evm.model.1.692 | NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | 81.1597 | 58.0026 | 33.3913 | 23.0803 | 29.9846 |

| EC 1.4.1.4 | evm.model.unitig_0.768 | aminating glutamate dehydrogenases | 86.8852 | 147.377 | 105.387 | 250.044 | 189.577 |

*Above the gene ID means the enzyme was located in mitochondrion.

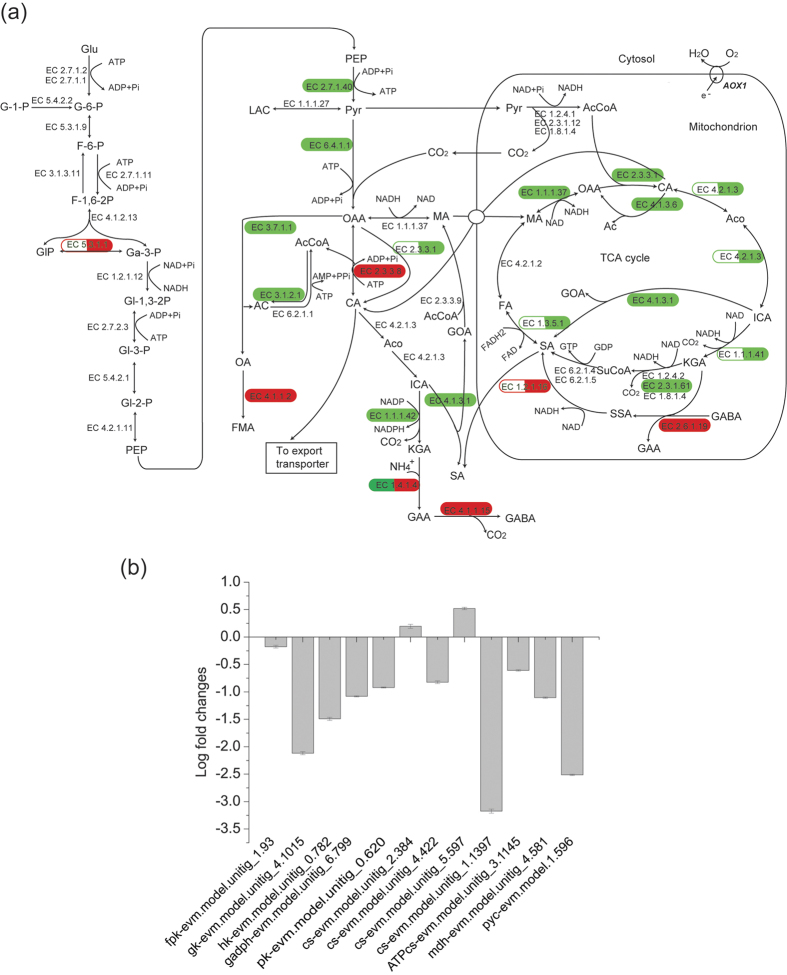

Figure 5. Transcription level regulation of genes in central metabolism.

(a) Transcription level regulation of genes in glycolysis and TCA cycle of H915-1 during citrate production. Red ellipse means up-regulated genes. Green ellipse means down-regulated genes. Half blank ellipse means that expression levels of some isoenzymes were not changed, while the other isoenzymes were affected. Abbreviations: GABA, 4-aminobutanoate; AC, acetate; AcA, acetaldehyde; AcCoA, acetyl-CoA; Aco, cis-aconitate; AOX1, alternative oxidase; CA, citrate; F-1,6–2P, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; ETH, ethonal; F-6-P, fructose 6-phosphate; FA, fumarate; FMA, formate; G-6-P, Glucose 6-phosphate; Ga-3-P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; GAA, glutamate; Glu, glucose; GI-1,3–2P, 3-phospho-D-glyceroyl phosphate; GI-2-P, 2-phospho-D-glycerate; GI-3-P, 3-phospho-D-glycerate; GIP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; GOA, glyoxylate; ICA, isocitrate; KGA, 2-oxoglutarate; MA, malate; OA, oxalate; OAA, oxaloacetate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; Pyr, pyruvate; SA, succinate; SSA, succinate semialdehyde; SuCoA, succinyl-CoA. (b) qPCR of gene expression fold changes of A1 at 60 h compared to H915-1 at 48 h. Error bars represent three technical replicates.

A triosephosphate isomerase was up-regulated 2-fold during citrate production. Because 1 mol d-fructose 1,6-bisphosphate decomposed into 1 mol dihydroxyacetone phosphate and 1 mol d-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, only d-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate remained as the substrate for the next enzyme in glycolysis. The triosephosphate isomerase must be up-regulated to form additional d-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate.

Phosphofructokinase (PFK1) was another key regulator in glycolysis. The expression level of PFK1 changed only slightly. PFK1 was inactivated by high concentrations of citrate, ATP, and manganese; however, the inhibition can be antagonized by NH4+ ions and fructose-2,6-bisphosphate42.

After glucose is catabolized to pyruvate, a part of the pyruvate is transported into the mitochondria to form acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which was the substrate of citrate synthase. There are 2 mitochondrial citrate synthases, all of which were down-regulated. The convesion rate of citrate did not seem to be a rate-limiting step for citrate production, and flux in citrate synthesis stage might even be reduced compared to that at 6 h.

The reactions that followed citrate synthase in the TCA cycle were all down-regulated at the transcription level. Among 4 predicted aconitases, 2 mitochondrial enzymes were highly transcribed and their expression levels decreased. Of the 3 isocitrate dehydrogenases in A. niger H915-1, the cytosolic NADP+-dependent form and 1 mitochondrial NAD+-dependent form were down-regulated.

2-Oxoglutarate (KGA) dehydrogenase was repressed at both the transcriptional level and the post-translation level6, and the GABA shunt pathway was up-regulated for succinate acid supplementation. KGA and GABA were catalyzed to produce succinate semialdehyde, which was further transformed to succinate. This situation is identical to that observed in A. niger CBS 513.88, which depends completely on the alternative respiration pathway because the succinate-CoA ligase complex is absent during fermentation according to transcription data4. This pathway is also important for KGA production in Yarrowia lipolytica43.

The intermediate glutamate enhances acid tolerance by consuming intracellular protons via amino acid decarboxylation, which helps increase intracellular pH44,45. The pathway is also involved in the release of NH4+ ions into the cytosol, which antagonizes citrate inhibition of phosphofructokinase6.

The oxaloacetate was formed either from TCA cycle or rTCA cycle. The former way lose two moles of carbon dioxide, while the latter way associated with fixing CO2 to pyruvate by pyruvate carboxylase to form oxaloacetic acid (OAA), which is subsequently reduced to malate by malate dehydrogenase and enters the mitochondria via a malate-citrate antiporter. Subsequently, malate participates in the TCA cycle and forms citrate. A. niger H915-1 contained 2 genes for pyruvate carboxylase, and only the cytosolic gene was observed to be transcribed. This gene was down-regulated dramatically to one-third the level observed at 6 h compared with citrate-synthesis-stage. For the 3 cytosolic malate dehydrogenases, only one was dramatically transcribed during fermentation, and malate dehydrogenase located in the mitochondrion was down-regulated.

Most of the genes in central metabolism were reported to be down regulated during citrate fermentation compared to cell-growing-phase, and the explanation for this situation was that as the broth pH decreased to extreme low level, the basic cell metabolism was down regulated for response of low pH. Though the expression was down-regulated, the expression level of FPKM was still high for citrate formation. The noticeable high metabolism during cell-growing-phase was reasonable because the cell weight was increased dramatically during the first 12 h (Fig. 2). As the major genes of central metabolism were identified, the genes expression level of strain A1 at 60 h was analyzed by qPCR compared to H915-1 at 48 h (Fig. 5b) and most of the genes were depressed in A1, indicating the higher genes expression level was responsible for higher citrate production.

Up-regulation of ATP-citrate lyases coordinate with the alternative respiratory pathway for energy balance

During citrate fermentation, energy balance was important because the conversion of citrate from glucose generated 1 mol ATP and 3 molecules of NADH, which was redundant and needed to be consumed46. The alternative pathway took charge of oxidizing excess NADH without forming ATP and the alternative oxidase was the core enzyme in the pathway47. In this study, the expression of alternative oxidase was mostly up-regulated at citrate-synthesis-phase compared to cell-growing-phase, confirming the importance of the pathway for citrate fermentation8. Nevertheless, the expression levels of alternative oxidase were low compared to other major genes of central metabolism, indicating that the other pathway for ATP consumption may be needed to help balance the energy. Notably, 2 cytosolic ATP-citrate lyases were up-regulated, which took part in a futile cycle. The mitochondrial citrate was transported to the cytoplasm, most of which was transported outside the cell and a small amount was catalyzed to generate OAA by ATP-citrate lyase with ATP consumption. Subsequently, OAA was transformed to malate and resupplied for mitochondrial citrate formation. This cycle consumed 1 mol ATP and the up-regulation of 2 cytosolic ATP-citrate lyases indicated that the pathway may help releaseing the pressure of the alternative respiration pathway for the recycling of NADH.

Regulation of heteroacid formation genes

A. niger strives to produce - at a given pH - the organic acid that most efficiently acidifies the medium. A. niger can produce several organic acids, including gluconate, oxalate, lactate, malate, succinate, and citrate48. Gluconate and oxalate are the main heteroacids that affect citrate production under certain conditions49. The secretion of heteroacid acids helps to decrease medium pH to below 3.0, which is crucial for citrate production6,48, and after citrate formation was triggered, the major role for acidification the medium was played by citrate. The expression profiles of genes involved in the formation of the primary heteroacids are shown in Supplementary Table S9.

The oxaloacetate acetylhydrolase (evm.model.unitig_6.59) catalyzed the degradation of oxaloacetate to form oxalate and acetate. The oah gene was highly expressed at 6 h of fermentation, which was in agreement with the report by Ruijter et al. (1999) that oxalate is the preferred acid in a strain capable of producing organic acids, and in Andersen’s stoichiometric model of A. niger metabolism, that the simulations predicted oxalate as the only produced organic acid throughout the pH range from 1.5 to 6.548.

Subsequently, the expression of oah gene was depressed and oxalate decarboxylase (evm.model.1.1180) was expressed at a constitutively high level during the citrate production period, thereby guaranteeing the elimination of oxalate after citrate begun to form and citrate became the major acid in the medium, and the situation also agreed with the Andersen’s stoichiometric model that citrate is the optimal acid for medium acidification when oxalate cannot be produced when pH ranged from 1.5 to 2.548. The reason of the trait remains obscure, but it may be an evolutionary strategy and one of the hypotheses suggests that low pH helps degrade plant cell walls, facilitating saprotrophic living of fungus, that it inhibits the growth of competing organisms, and that the acids chelate trace metals, making them available to the fungus50.

At the same time of oxalic acid formation, the same amount of acetate was produced in cytosol by oxaloacetate hydrolase. In addition, high expression level of acetyl-CoA hydrolase (evm.model.unitig_6.429) at 6 h further increased the acetate synthesis in A. niger. Nevertheless, acetate accumulation did not occur in the medium, suggesting the catabolic rate of acetate was sufficient to prevent its formation as Ruijter et al. (1999) reported. The result was also in agreement with the simulations predict by Andersen et al. (2009) that it is more energetically efficient to re-metabolize acetate than to use it for acidification of the medium. However, in the later fermentation phase, the expression levels of both oxaloacetate acetylhydrolase and acetyl-CoA hydrolase were dramatically down-regulated, indicating the decrease of acetate pathway and a main metabolite flux into the TCA cycle for citrate production.

A. niger H915-1 had only 1 glucose oxidase (evm.model.unitig_0.36), which was an extracellular enzyme and catalyzed the formation of gluconic acid from glucose in broth. The enzyme was only expressed during the early stage of fermentation but silent later. This result was in agreement with the report that gluconic acid is an early product during citrate fermentation51. In addition, the enzyme was inactivated at pH values below 3.5, and this further guaranteed the elimination of gluconic acid formation when producing citrate6.

Regulation of transporters

Elucidating the transport of both sugars and citrate is crucial to understanding citrate overproduction by A. niger. However, disagreement exists about the mechanisms underlying both the uptake of glucose and the secretion of citrate ions. Overall, 46 transporters were expressed differently at the transcriptional level during citrate production (Table 3).

Table 3. Transporters regulated on transcriptional level during citrate fermentation.

| Gene ID | Gene function | FPKM-6h | FPKM-12h | FPKM-24h | FPKM-36h | FPKM-48h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| evm.model.unitig_3.636 | ABC transporter C family member | 13.1977 | 35.3317 | 58.9041 | 46.401 | 37.9172 |

| evm.model.unitig_3.637 | Canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter 1 | 28.5373 | 87.9929 | 149.208 | 97.0309 | 73.4379 |

| evm.model.unitig_3.640 | Canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter 1 | 20.4793 | 107.35 | 223.035 | 296.068 | 305.751 |

| evm.model.unitig_0.1084 | Canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter 2 | 8.0014 | 40.5062 | 79.4721 | 84.8434 | 60.4354 |

| evm.model.unitig_5.1021 | Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit alpha-1 | 63.2289 | 130.481 | 286.188 | 272.621 | 353.328 |

| evm.model.1.100 | succinate/fumarate transporter | 60.1747 | 7.32488 | 4.93716 | 3.10826 | 7.87887 |

| evm.model.1.1208 | Uncharacterized transporter | 20.1262 | 657.514 | 638.877 | 605.893 | 604.348 |

| evm.model.1.31 | Probable metabolite transport protein | 19.7919 | 47.7725 | 103.538 | 138.268 | 150.005 |

| evm.model.1.352 | plasma membrane fusion protein prm1 | 4.66831 | 21.8264 | 107.014 | 162.537 | 109.181 |

| evm.model.1.69 | amino acid transporter | 26.4711 | 6.00714 | 4.01169 | 3.26287 | 4.30079 |

| evm.model.1.857 | Uncharacterized MFS-type transporter | 262.407 | 35.7379 | 29.1139 | 28.839 | 18.9121 |

| evm.model.unitig_0.1595 | Uncharacterized transporter | 7.69787 | 24.2853 | 42.5223 | 80.5382 | 81.6519 |

| evm.model.unitig_0.437 | quinate permease | 2.52556 | 23.0903 | 55.1789 | 28.4854 | 22.4314 |

| evm.model.unitig_1.1394 | MFS multidrug transporter | 1144.22 | 178.003 | 114.492 | 36.4788 | 28.1839 |

| evm.model.unitig_1.578 | Mitochondrial 2-oxodicarboxylate carrier 2 | 826.306 | 390.695 | 405.997 | 283.533 | 284.765 |

| evm.model.unitig_2.1188 | amino-acid permease inda1 | 157.845 | 440.541 | 549.456 | 578.762 | 548.658 |

| evm.model.unitig_2.1237 | MFS transporter | 16.3143 | 61.9491 | 77.3993 | 77.3265 | 65.6228 |

| evm.model.unitig_2.1258 | Glutathione transporter 1 | 53.949 | 4.04985 | 2.2213 | 1.01079 | 0.489433 |

| evm.model.unitig_2.1390 | vacuolar calcium ion transporter | 252.61 | 622.261 | 657.009 | 600.778 | 603.315 |

| evm.model.unitig_2.1392 | vacuolar calcium ion transporter | 32.1809 | 68.8772 | 91.3865 | 94.9701 | 77.2152 |

| evm.model.unitig_2.45 | MFS transporter | 38.4455 | 12.7329 | 3.27757 | 1.25471 | 0.357967 |

| evm.model.unitig_2.532 | calcium transporter | 53.9308 | 119.391 | 153.595 | 189.557 | 130.659 |

| evm.model.unitig_2.827 | urea active transporter 1 | 15.9503 | 43.262 | 77.2426 | 53.5096 | 52.18 |

| evm.model.unitig_2.971 | corA family metal ion transporter | 7.22867 | 189.826 | 347.136 | 300.912 | 301.19 |

| evm.model.unitig_3.1075 | galactose-proton symport | 687.339 | 254.727 | 116.009 | 82.0497 | 93.8167 |

| evm.model.unitig_3.1191 | quinate permease | 0 | 25.5055 | 36.3913 | 25.114 | 34.4627 |

| evm.model.unitig_3.62 | ABC transporter | 39.1748 | 78.3932 | 116.238 | 125.325 | 118.615 |

| evm.model.unitig_3.635 | Oligopeptide transporter | 14.6011 | 104.855 | 128.548 | 199.55 | 116.732 |

| evm.model.unitig_4.1038 | Uncharacterized permease | 63.5294 | 161.174 | 243.495 | 213.192 | 141.02 |

| evm.model.unitig_4.1122 | Zinc-regulated transporter 1 | 26.221 | 868.686 | 1163.35 | 831.676 | 662.476 |

| evm.model.unitig_4.29 | MFS multidrug transporter | 28.1368 | 65.3458 | 79.5197 | 108.998 | 84.1431 |

| evm.model.unitig_4.558 | sugar transporter | 60.7082 | 28.922 | 24.2149 | 12.3733 | 23.8319 |

| evm.model.unitig_4.58 | zinc-regulated transporter 1 | 27.4409 | 86.7798 | 89.9594 | 104.495 | 106.612 |

| evm.model.unitig_4.660 | MFS allantoate transporter | 9.26185 | 27.5775 | 126.026 | 91.9883 | 92.9983 |

| evm.model.unitig_4.694 | Transport protein particle 20 kDa subunit | 71.691 | 35.4592 | 31.7326 | 35.1786 | 31.681 |

| evm.model.unitig_4.966 | copper transporter family protein | 89.4315 | 386.8 | 247.155 | 674.724 | 409.464 |

| evm.model.unitig_5.1028 | Oligopeptide transporter | 427.735 | 1076.43 | 1775.18 | 1632.03 | 1598.71 |

| evm.model.unitig_6.240 | corA family metal ion transporter | 89.6403 | 201.674 | 232.638 | 230.226 | 243.676 |

| evm.model.unitig_6.447 | monocarboxylate transporter | 50.1323 | 135.575 | 189.269 | 239.416 | 254.186 |

| evm.model.unitig_6.486 | low affinity iron transporter | 3.69287 | 73.9308 | 190.217 | 325.134 | 557.337 |

| evm.model.unitig_6.549 | Purine-cytosine permease fcyB | 59.0138 | 194.498 | 328.304 | 284.184 | 176.873 |

| evm.model.unitig_6.821 | MFS toxin efflux pump | 49.4076 | 103.654 | 164.539 | 173.255 | 159.919 |

| evm.model.unitig_6.853 | Choline transport protein | 3.65766 | 51.889 | 48.6358 | 93.561 | 47.9792 |

| evm.model.unitig_6.875 | MFS transporter | 2.1797 | 23.2597 | 24.884 | 45.0643 | 33.2642 |

| evm.model.unitig_3.110 | Hexose transporter | 5.8594 | 29.5108 | 54.735 | 74.547 | 275.829 |

| evm.model.unitig_3.919 | OPT oligopeptide transporter family | 3.40145 | 42.7754 | 192.636 | 367.982 | 323.622 |

Both simple diffusion and sugar transporters were found responding for glucose uptake during citrate producing52,53,54. In this study, 28 sugar transporters were expressed, among which a low-affinity glucose transporter (evm.model.unitig_0.1567) was constitutively expressed during fermentation at high level, and 5 high-affinity glucose transporters were expressed constitutively at low level, and a hexose transporter was up-regulated. The result supported the suggestion that a low-affinity glucose transporter has a major function in glucose catabolism among all sugar transporters55. Nevertheless, the low-affinity glucose transporter was formed when grown on a high (15% w/v) glucose concentration in previous report55, but in this work, the transporter could be constitutively expressed during citrate fermentation even at 48 h when the glucose concentration decreased to 8%. Furthermore, the roles of high-affinity glucose transporters could be confirmed as glucose can be consumed entirely in late stage6.

The mechanism for citrate transportation through the plasma membrane requires further study. Because a dramatic pH gradient exists between the plasma and the extracellular medium, citrate is produced mainly as citrate2− in the cytosol (with a pH between 6.0 and 7.0) and as an undissociated form of acid in medium (with a pH below 2.0)56. Citrate2− can be secreted from A. niger into broth, and the hyphae can take up citrate at the end of citrate fermentation, which indicates that both of the 2 forms of citrate can cross the cell wall. Nevertheless, no citrate transporter has yet been identified. In this study, 35 transporters were identified as being up-regulated during citrate fermentation, among which 3 organic anion transporters, a low-affinity iron transporter, and a monocarboxylate transporter were found. In addition, the transcription levels of 11 uncharacterized transporters increased. These transporters constituted candidate citrate transporters.

Regulation of genes involving cell wall components

The main cell wall of A. niger contains β-1, 3-glucan, chitin, β-1, 6-glucan, α-1, 3-glucan, galactosaminogalactan, and galactomannan57. We found that expression levels of several genes involved in cell wall integrity were up-regulated during citrate production (Supplementary Table S10). Chitin synthase C was highly up-regulated. Pst1 was previously identified as a cell surface glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein important for cell wall integrity58,59 and the expression of PST1 increased during fermentation, helping maintain cell wall strength for resistance to the low pH of the medium. The α-1,3-glucan usually exists on the cell wall of conidia and glues melanin to the conidial surface60, and it also plays an essential role in the aggregation of conidia61,62. The expression of alpha-1, 3-glucan synthase ags1 was up-regulated during citrate fermentation, which indicated that it might also play a role in the aggregation of hypha. In addition, UDP-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase and N-acetylglucosaminidase were both up-regulated, which indicated the synthesis of various types of glycoproteins and N-glycans63. Furthermore, 3 endoglucanases were down-regulated to reduce cell wall degradation.

Elimination of oxalate formation and increased citrate production through deletion of oah in A. niger

A. niger H915-1 expressed oah dramatically and resulted in oxalate synthesis early in the fermentation process. The role of oxalate on citrate production still needed to be confirmed. The production of oxalate may facilitated the acidification of medium and guarantee a low pH for citrate fermentation. However, the synthesis of oxalate may drain metabolites used for cell growth and influence subsequent citrate fermentation. As a result, the oah gene was knocked out to examine its role in citrate fermentation.

We obtained an oah gene deletion strain (Fig. 6a and b) and found that when the length of the flanking DNA reached 2.3 kb, the homologous recombination rate was 65%. During citrate fermentation in A. niger H915-1, oxalate was synthesized earlier than citrate and then eliminated later in the fermentation phase. When oah was deleted, the strain no longer synthesized oxalate (Fig. 6c). The pH during fermentation between H915-1 and H915 (Δoah::hph) was not different, indicating that though oxalate production had impact on pH decrease, it was not the decisive factor due to diverse organic acids synthesized by A. niger. In addition, the deletion of oah in H915-1 did not influence the biomass either, suggesting the extremely high expression of oah drained little flux from cell growth, which was the same with the phenomenon of oah-deleting A. niger strain for enzyme production64. Finally, the influence of citrate production through the deletion of oah was not significant. Though the citrate yield was up-regulated by 1.7% (Supplementary Table S11), the difference was not statistical significant by t-test.

Figure 6. Deletion of oah in A. niger resulted in oxalate eliminated and slightly increased citrate production yield.

(a) A graphical representation showing gene deletion of oah in A. niger and primers used for validation of recombinated genome. (b) PCR products of the sequences down-stream of oah using primers P3 and P4 (upper) and oah gene using primers P1 and P2 (below). Lane 1–20, A. niger transformants; Lane CK, wild type of H915-1; Lane M, DNA ladder. (c) Citrate and oxalate production of H915-1 and H915 (Δoah::hph).

Conclusion

The genome of industrial citrate-producing A. niger strain H915-1 was sequenced and compared with genomes of 2 strains that produce citrate at lower levels. SNP analysis revealed differences at 57 sites and 35 SVs in various genes in the A. niger H915-1 genome. These genes were involved in the TCA cycle, GABA shunt pathway, and other pathways. Transcriptome analysis of A. niger H915-1 during citrate fermentation showed that among the genes expressed during the cell growth stage (6 h), 479 genes were expressed differently at all 4 time-points of the citrate production stage (12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h). The data showed the expression profile of the major genes in the involved pathways. The up-regulation of ATP-citrate synthase may coordinate with the alternative respiratory pathway for energy balance. Furthermore, 35 transporters were up-regulated, which identified previously unknown candidate citrate transporters. In addition, to solve the problems of abundantly expressed oah and oxalate formation during the early phase of fermentation, we knocked out oah in A. niger H915-1, which neither affected citrate production nor influenced acidification of medium. The results of this study revealed the mechanism of citrate production in A. niger and contribute to future rational metabolic design.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yin, X. et al. Comparative genomics and transcriptome analysis of Aspergillus niger and metabolic engineering for citrate production. Sci. Rep. 7, 41040; doi: 10.1038/srep41040 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by 111 Project (111-2-06) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Footnotes

Author Contributions X.Y. designed and performed the experiments. J.L., H.S., L.L., G.D. and J.C. conceived the project, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

References

- Andersen M. R. et al. Comparative genomics of citric-acid-producing Aspergillus niger ATCC 1015 versus enzyme-producing CBS 513.88. Genome Research 21, 885–897 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X. et al. Metabolic engineering in the biotechnological production of organic acids in the tricarboxylic acid cycle of microorganisms: Advances and prospects. Biotechnol Adv 33, 830–841 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S. E. Aspergillus niger genomics: past, present and into the future. Medical mycology 44 Suppl 1, S17–21 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen M. R., Nielsen M. L. & Nielsen J. Metabolic model integration of the bibliome, genome, metabolome and reactome of Aspergillus niger. Mol Syst Biol 4 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaffa L. & Kubicek C. P. Aspergillus niger citric acid accumulation: do we understand this well working black box? Appl Microbiol Biot 61, 189–196 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagianni M. Advances in citric acid fermentation by Aspergillus niger: biochemical aspects, membrane transport and modeling. Biotechnology advances 25, 244–263 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Lu X., Rinas U. & Zeng A. P. Metabolic peculiarities of Aspergillus niger disclosed by comparative metabolic genomics. Genome Biol 8, R182 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirimura K., Ogawa S., Hattori T. & Kino K. Expression analysis of alternative oxidase gene (aox1) with enhanced green fluorescent protein as marker in citric acid-producing Aspergillus niger. J Biosci Bioeng 102, 210–214 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. et al. Linkage of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunctions to spontaneous culture degeneration in Aspergillus nidulans. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 13, 449–461 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shats V., Filov V. A. & Maksimova O. V. On the determination of sugar in biological fluids using dinitrosalicylic acid. Lab Delo 11, 663–665 (1966). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. R. et al. Aggressive assembly of pyrosequencing reads with mates. Bioinformatics 24, 2818–2824 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin C. S. et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nature methods 10, 563–569 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaisson M. J. & Tesler G. Mapping single molecule sequencing reads using basic local alignment with successive refinement (BLASR): application and theory. Bmc Bioinformatics 13, 238 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer D. D., Delcher A. L., Salzberg S. L. & Pop M. Minimus: a fast, lightweight genome assembler. Bmc Bioinformatics 8, 64 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M., Schoffmann O., Morgenstern B. & Waack S. Gene prediction in eukaryotes with a generalized hidden Markov model that uses hints from external sources. Bmc Bioinformatics 7, 62 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. Bmc Bioinformatics 5, 59 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besemer J. & Borodovsky M. GeneMark: web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic Acids Res 33, W451–454 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E., Clamp M. & Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Research 14, 988–995 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol 9, R7 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe T. M. & Eddy S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 25, 955–964 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagesen K. et al. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 35, 3100–3108 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J. et al. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res 110, 462–467 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Stoeckert C. J. Jr. & Roos D. S. Ortho MCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Research 13, 2178–2189 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6, 80–92 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Pachter L. & Salzberg S. L. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25, 1105–1111 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology 28, 511–U174 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. et al. Construction of a foodgrade xylanase engineering strain of Aspergillus niger. Journal of Northeast Agricultural University 44, 7–13 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Blumhoff M., Steiger M. G., Marx H., Mattanovich D. & Sauer M. Six novel constitutive promoters for metabolic engineering of Aspergillus niger. Appl Microbiol Biot 97, 259–267 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijgsheld P. et al. Development in Aspergillus. Stud Mycol 74, 1–29 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au K. F., Underwood J. G., Lee L. & Wong W. H. Improving PacBio Long Read Accuracy by Short Read Alignment. Plos One 7 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarini M. et al. An evaluation of the PacBio RS platform for sequencing and de novo assembly of a chloroplast genome. Bmc Genomics 14 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski M., Barciszewska M. Z., Erdmann V. A. & Barciszewski J. 5S Ribosomal RNA Database. Nucleic Acids Res 30, 176–178 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm L. H. et al. Kinetic studies on the aggregation of Aspergillus niger conidia. Biotechnol Bioeng 87, 213–218 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P. J., Grimm L. H., Wulkow M., Hempel D. C. & Krull R. Population balance modeling of the conidial aggregation of Aspergillus niger. Biotechnol Bioeng 99, 341–350 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynesen J. & Nielsen J. Surface hydrophobicity of Aspergillus nidulans conidiospores and its role in pellet formation. Biotechnology progress 19, 1049–1052 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veluw G. J. et al. Heterogeneity in liquid shaken cultures of Aspergillus niger inoculated with melanised conidia or conidia of pigmentation mutants. Studies in mycology 74, 47–57 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartnicki-Garcia S. Cell wall chemistry, morphogenesis, and taxonomy of fungi. Annu Rev Microbiol 22, 87–108 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D. J., Kjellbom P. & Lamb C. J. Elicitor- and wound-induced oxidative cross-linking of a proline-rich plant cell wall protein: a novel, rapid defense response. Cell 70, 21–30 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka J. & Hazen K. C. Cell wall protein mannosylation determines Candida albicans cell surface hydrophobicity. Microbiology 143, 3015–3021 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumberger N., Ringli C. & Keller B. The chimeric leucine-rich repeat/extensin cell wall protein LRX1 is required for root hair morphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev 15, 1128–1139 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbock F., Choojun S., Held I., Roehr M. & Kubicek C. P. Characterization and regulatory properties of a single hexokinase from the citric acid accumulating fungus Aspergillus niger. Biochim Biophys Acta 1200, 215–223 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek-Pranz E. M., Mozelt M., Rohr M. & Kubicek C. P. Changes in the concentration of fructose 2,6-bisphosphate in Aspergillus niger during stimulation of acidogenesis by elevated sucrose concentration. Biochim Biophys Acta 1033, 250–255 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilchenko A., Lysyanskaya V. Y., Finogenova T. & Morgunov I. Characteristic properties of metabolism of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica during the synthesis of α-ketoglutaric acid from ethanol. Microbiology 79, 450–455 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Richard H. & Foster J. W. Escherichia coli glutamate- and arginine-dependent acid resistance systems increase internal pH and reverse transmembrane potential. J Bacteriol 186, 6032–6041 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter P. D., Ryan S., Gahan C. G. & Hill C. Presence of GadD1 glutamate decarboxylase in selected Listeria monocytogenes strains is associated with an ability to grow at low pH. Appl Environ Microbiol 71, 2832–2839 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirimura K. et al. Contribution of cyanide-insensitive respiratory pathway, catalyzed by the alternative oxidase, to citric acid production in Aspergillus niger. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 64, 2034–2039 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B. A. et al. A broad distribution of the alternative oxidase in microsporidian parasites. Plos Pathog 6, e1000761 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen M. R., Lehmann L. & Nielsen J. Systemic analysis of the response of Aspergillus niger to ambient pH. Genome Biol 10 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruijter G. J., van de Vondervoort P. J. & Visser J. Oxalic acid production by Aspergillus niger: an oxalate-non-producing mutant produces citric acid at pH 5 and in the presence of manganese. Microbiology 145 (Pt 9), 2569–2576 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen H., Hjort C. & Nielsen J. Cloning and characterization of oah, the gene encoding oxaloacetate hydrolase in Aspergillus niger. Molecular and General Genetics MGG 263, 281–286 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S., Fontanille P., Pandey A. & Larroche C. Gluconic acid: Properties, applications and microbial production. Food Technol Biotech 44, 185–195 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Torres N. V. Modeling approach to control of carbohydrate metabolism during citric acid accumulation by Aspergillus niger: 2. Sensitivity analysis. Biotechnol Bioeng 44, 112–118 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres N. V. Modeling approach to control of carbohydrate-metabolism during citric acid accumulation by Aspergillus niger:1. Model definition and stability of the steady state. Biotechnol Bioeng 44, 104–111 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagianni M. & Mattey M. Modeling the mechanisms of glucose transport through the cell membrane of Aspergillus niger in submerged citric acid fermentation processes. Biochem Eng J 20, 7–12 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Torres N., Riol-Cimas J., Wolschek M. & Kubicek C. Glucose transport by Aspergillus niger: the low-affinity carrier is only formed during growth on high glucose concentrations. Appl Microbiol Biot 44, 790–794 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Kontopidis G., Mattey M. & Kristiansen B. Citrate transport during the citric-acid fermentation by Aspergillus niger. Biotechnol Lett 17, 1101–1106 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Pel H. J. et al. Genome sequencing and analysis of the versatile cell factory Aspergillus niger CBS 513.88. Nature biotechnology 25, 221–231 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo M. et al. PST1 and ECM33 encode two yeast cell surface GPI proteins important for cell wall integrity. Microbiology 150, 4157–4170 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Bona A. et al. Candida albicans cell shaving uncovers new proteins involved in cell wall integrity, yeast to hypha transition, stress response and host-pathogen interaction. J Proteomics 127, 340–351 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latge J. P. Tasting the fungal cell wall. Cell Microbiol 12, 863–872 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorais F. et al. Cell wall glucan synthases and GTPases in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Med Mycol 48, 35–47 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine T. et al. Cell wall alpha1-3 glucans induce the aggregation of germinating conidia of Aspergillus fumigatus. Fungal Genet Biol 47, 707–712 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Tsuji Y., Matsushita S., Kumagai H. & Tochikura T. Purification and Properties of beta-N-Acetylhexosaminidase from Mucor fragilis Grown in Bovine Blood. Appl Environ Microbiol 51, 1019–1023 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen H., Christensen B., Hjort C. & Nielsen J. Construction and characterization of an oxalic acid nonproducing strain of Aspergillus niger. Metab Eng 2, 34–41 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.