Abstract

We previously produced, in Escherichia coli, a human monoclonal antibody Fab fragment, CP33, specific for the galactose- and N-acetyl-d-galactosamine-inhibitable lectin of Entamoeba histolytica. To prepare antibodies with a higher affinity to the lectin, recombination PCR was used to exchange Ser91 and Arg96 in the third complementarity-determining region of the light chain with other amino acids. The screening of 200 clones of each exchange by an indirect fluorescent antibody test showed that 14 clones for Ser91 and nine clones for Arg96 reacted strongly with E. histolytica trophozoites. Sequence analyses revealed that the substituted amino acids at Ser91 were Ala in five clones, Gly in three clones, Pro in two clones, and Val in two clones, while the amino acid at position 96 was substituted with Leu in three clones. The remaining eight clones exhibited no amino acid change at position 91 or 96. These mutant Fab fragments were purified and subjected to a surface plasmon resonance assay to measure the affinity of these proteins to the cysteine-rich domain of lectin. Pro or Gly substitution for Ser91 caused an increased affinity of the Fab, but substitution with Ala or Val did not. The replacement of Arg96 with Leu did not affect affinity. These results demonstrate that modification of antibody genes by recombination PCR is a useful method for affinity maturation and that amino acid substitution at position 91 yields Fabs with increased affinity for the lectin.

Amebiasis caused by infection with the intestinal protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica is a notable parasitic disease in both developing and developed countries. It has been estimated that 50 million people develop amebic colitis and extraintestinal abscesses, resulting in up to 110,000 deaths annually (18). The development of immunoprophylaxis and accurate diagnostic tools is important for the control of amebiasis. The application of monoclonal antibodies is a promising avenue of research for improvement in diagnosis.

We recently produced several human monoclonal antibody Fab fragments specific for E. histolytica in Escherichia coli by use of combinatorial immunoglobulin gene libraries constructed from the peripheral lymphocytes of a patient with an amebic liver abscess and from an asymptomatic cyst passer (1, 14, 17). One of the Fab clones, CP33, derived from the asymptomatic cyst passer, recognized the cysteine-rich domain of the heavy subunit of the galactose- and N-acetyl-d-galactosamine-inhibitable (Gal/GalNAc) lectin (12) of E. histolytica (17). This clone exhibited neutralizing activities to amebic adherence and to erythrophagocytosis. Furthermore, we produced the Fab fragment fused with alkaline phosphatase for diagnostic purposes (16).

Recombinant antibody technology makes it possible to introduce site-directed or random mutations in the original antibody gene (3-5, 13, 19). Residues in the complementarity-determining region (CDR), especially in CDR3 of both the heavy and light chains of antibody, are considered responsible for high-energy interactions with antigen. Therefore, mutations at these residues will likely abolish antigen binding. However, an increased affinity may also occur by mutation if the native residue exhibits a negative effect on the interaction. In the Kabat numbering system, CDR3 of the light chain is the amino acid segment from position 89 to 97 (6, 20). The corresponding amino acid residues in CP33 were GlnGlnSerTyrSerThrProArgThr (17). When an additional 13 light chains which constitute antilectin Fabs with the heavy chain of CP33 were analyzed, high variability was observed at positions 91, 92, 94, and 96 (17). As a first step in the affinity maturation of human antibodies to E. histolytica, we attempted to modify Fab clone CP33 by single-amino-acid substitutions of Ser91 and Arg96 in the light chain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site-directed mutagenesis.

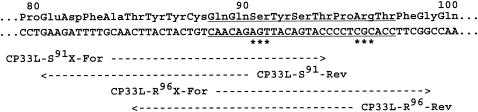

Site-directed mutagenesis in the light chain gene of CP33 (17) was performed by recombination PCR (7). The plasmid vector pFab1-His2, containing the light and the Fd region of the heavy chain genes, was amplified by using two sets of primers, CP33L-S91X-For (5′-CAACTTACTACTGTCAACAGNNNTACAGTAC-3′, where N is any nucleotide) and CP33L-S91-Rev (5′-CTGTTGACAGTAGTAAGTTGCAAAATCTTC-3′), and CP33L-R96X-For (5′-AACAGAGTTACAGTACCCCTNNNACCTTCGG-3′) and CP33L-R96-Rev (5′-AGGGGTACTGTAACTCTGTTGACAGTAGTAAG-3′). The positions of these primers in the light-chain gene of CP33 are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Positions of the four primers used in recombination PCR of the light-chain gene of CP33. The partial nucleotide sequence and the deduced amino acid sequence of the light-chain gene are shown. Numbers above the sequence indicate amino acid positions in the Kabat numbering system. CDR3 is underlined. The locations of the nucleotides where mutations were introduced are indicated by asterisks. Dashed lines and arrowheads indicate the corresponding sites and directions of the primers.

To obtain high fidelity amplification, Pyrobest DNA polymerase (Takara, Otsu, Japan) was used. Twenty-five cycles of PCR were performed as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 15 s (135 s in cycle 1), annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and polymerization at 72°C for 360 s. The PCR products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and by use of a Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The DNA fragments were introduced into E. coli JM109 cells.

Expression of Fabs and screening.

Bacterial expression of Fabs was performed essentially as previously described (14). Each clone was cultured in 2 ml of super broth (30 g of tryptone, 20 g of yeast extract, 10 g of morpholinepropanesulfonic acid per liter [pH 7]) containing ampicillin until an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4 to 0.6 was achieved. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to the bacterial cultures to a final concentration of 0.1 mM, and the cells were then cultured for a further 12 h at 30°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in 150 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and then ruptured by sonication. After centrifugation of the lysates at 18,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was screened by an indirect fluorescent antibody test.

Indirect fluorescent antibody test.

Trophozoites of E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS were cultured axenically in BI-S-33 medium (2) supplemented with 10% adult bovine serum at 37°C. Trophozoites of Entamoeba dispar SAW1734RclAR were cultured monoxenically with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in BCSI-S medium at 37°C (9). These trophozoites at the logarithmic phase of growth were used in the following experiments. The indirect fluorescent antibody test was performed with formalin-fixed trophozoites as described previously (15). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat immunoglobulin G to human immunoglobulin G Fab (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Aurora, Ohio) was used as the secondary antibody.

For confocal laser scanning microscopy, E. histolytica trophozoites were transferred onto glass coverslips in a culture dish containing medium and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After removal of the medium, the coverslips were incubated in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. The trophozoites were washed with PBS and then permeabilized by treatment with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature. The trophozoites were again washed with PBS and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Purified Fab was added, and the coverslips were incubated for 12 h at 4°C. The coverslips were washed with PBS and then incubated with the secondary antibody for 5 h at 4°C. The coverslips were again washed with PBS and then stained with 2.5 μg of propidium iodide per ml for 10 min at room temperature. We used an LM410 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss Vision GmbH, Hallbergmoos, Germany) to observe the samples.

DNA sequencing.

Plasmid DNA was isolated from the indirect fluorescent antibody-positive clones. Light-chain genes in the expression vector were subcloned into sequencing vector. Sequencing in both directions was performed with a BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with M13 primers. The reactions were run on an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Purification of Fabs.

Selected positive clones were cultured in 400 ml of medium. The cells were disrupted and the supernatant was prepared as described above. Purification of Fabs in the supernatant was achieved by affinity chromatography with His•Bind resin (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Purified Fabs were solubilized with an equal volume of sample buffer (10) containing 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM N-α-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone, and 4 μM leupeptin for 5 min at 95°C and then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions.

Determination of affinity constants.

The affinity constants of Fabs were assessed by surface plasmon resonance with the BIAcore 3000 instrument (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden), according to the general procedure outlined by the manufacturer (8). The cysteine-rich domain of the Gal/GalNAc lectin heavy subunit, rLecA (11), kindly provided by W. A. Petri, Jr., University of Virginia, was immobilized onto a CM5 chip (Biacore) surface at a low density by amine coupling chemistry. Association and dissociation constants were determined by using the software of the manufacturers, BIAevaluation 3.1.

RESULTS

Amino acid modifications at positions 91 and 96.

Transformation of E. coli with two kinds of PCR products yielded more than 104 colonies. Of these, 200 clones of each exchange were randomly selected and then cultured for the expression of Fabs. When E. coli extracts from those clones with a randomly mutated amino acid at position 91 were screened to detect Fab fragments reactive with formalin-fixed E. histolytica trophozoites, 37 positive samples were obtained. In the second screening, 10-fold-diluted samples of the E. coli extracts were also examined by indirect fluorescent antibody test. Fourteen samples were found to be strongly reactive with the E. histolytica trophozoites, which was comparable to the reactivity of the original clone CP33. Sequencing of the light-chain genes revealed that Ser91 of the light chain had been replaced by Ala in five clones, Gly in three clones, Pro in two clones, and Val in two clones. The remaining two clones showed no substitution at this amino acid, although the nucleotide sequences were changed. Interestingly, these four residues are grouped into the amino acids with nonpolar side chains. On the other hand, when the mutations were introduced at Arg96, nine clones were shown to be reactive with the E. histolytica trophozoites as strongly as the original clone CP33. Among these nine clones, three exhibited a replacement of Arg96 with Leu, while the other six showed no replacement.

Reactivity of the modified Fabs.

We selected one clone from each group with the same mutation at Fab. These clones were cultured on a large scale to obtain Fab fragments to be purified by affinity chromatography for the His tag. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the purified proteins demonstrated two bands with apparent molecular masses of 24 and 25 kDa under reduced conditions (data not shown). These purified Fabs were confirmed to be reactive with E. histolytica trophozoites by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Localization of bright fluorescence on the surface of the trophozoites was demonstrated by immunostaining with the modified antibody clones as well as with the unmodified antibody CP33 (data not shown). The specificity of the modified Fabs was also examined by indirect fluorescent antibody test. The Fabs were not reactive with E. dispar, indicating that amino acid modifications did not affect the specificity of these Fabs.

Affinity comparison of the modified Fabs.

The affinity of the purified Fabs to the antigen was assessed by surface plasmon resonance. As shown in Table 1, the association and dissociation constant values of clone 1 without the amino acid substitution were comparable to the values of CP33 reported in a previous paper (17). The affinity of the Fabs with Ser91Pro (clone 2) and Ser91Gly (clone 4) was found to be approximately 4.8- and 1.7-fold higher, respectively, than that of the original Fab. However, the mutants with Ser91Ala (clone 3) and Ser91Val (clone 5) exhibited dissociation constants comparable to those for clone 1 or CP33. On the other hand, the affinity of the Fab with Arg96Leu (clone 6) was comparable to that of CP33.

TABLE 1.

Association and dissociation constants of the binding of modified human Fab fragments to the cysteine-rich domain of the Gal/GalNAc lectin heavy subunit of E. histolytica, measured by surface plasmon resonance

| Fab | Amino acid change in light chain

|

Ka (1/M) | Increase compared to CP33 (fold) | Kd (M) | Decrease compared to CP33 (fold) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ser91 | Arg96 | |||||

| Clone 1 | Ser (AGC) | 5.53 × 107 | 0.8 | 1.81 × 10−8 | 0.8 | |

| Clone 2 | Pro (CCA) | 3.49 × 108 | 4.9 | 2.87 × 10−9 | 4.8 | |

| Clone 3 | Ala (GCG) | 6.38 × 107 | 0.9 | 1.57 × 10−8 | 0.9 | |

| Clone 4 | Gly (GGC) | 1.21 × 108 | 1.7 | 8.24 × 10−9 | 1.7 | |

| Clone 5 | Val (GTC) | 7.64 × 107 | 1.1 | 1.88 × 10−8 | 0.7 | |

| Clone 6 | Leu (CTG) | 4.95 × 107 | 0.7 | 2.02 × 10−8 | 0.7 | |

| CP33a | 7.19 × 107 | 1.0 | 1.39 × 10−8 | 1.0 | ||

These values are from a previous study (17).

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that a single-amino-acid replacement of Ser91 in CDR3 of the light chain could improve the affinity of CP33. A number of possible explanations for this observation occurred to us. First, the contribution of the Ser91 residue to the interaction between antigen and antibody was considered. Ser is a polar amino acid and therefore may contribute to binding affinity by forming a hydrogen bond to the amino acid of the lectin. However, this possibility is unlikely because hydrophobic amino acids such as Ala and Val are not able to form a hydrogen bond, but the substitution of Ser with Ala or Val appeared to have a lesser effect on the binding affinity of the antibody.

Second, it was considered that Ser91 might inhibit affinity through steric hindrance. The substitution of Ser with Pro leads to residue bending, which results in the conformational change which allowed the redistribution of the neighboring amino acids favoring the antigen-antibody interaction. The increased affinity of the antibody by the replacement of Ser with Gly supports the second consideration because Gly is the smallest amino acid and therefore is capable of reducing the steric hindrance caused by the Ser residue. Furthermore, this notion is consistent with the finding that the Ala and Val substitutions exhibited no effect on binding affinity because the sizes of Ala and Val residues are comparable to that of Ser. It is known that the effect of a mutation is not restricted to contact residues (19). Although the residue at position 91 may not react directly with antigenic molecules, it can affect the binding of residue 93 (5). Therefore, the second possibility seems more likely to be the explanation, although we cannot exclude other possibilities.

In contrast, improvement of affinity was not achieved by the single-amino-acid modification at Arg96. Since the amino acid change from Arg to Leu is thought to be drastic, it is reasonable to expect a distinct change in binding affinity. However, this was not the case. At present, the reason is not clear. As the nucleotide sequence has not been analyzed in all clones, there is the possibility that substitutions to amino acids translated from only one genetic code were not included in the mutagenesis of this study. However, since 200 clones were examined, the probability that the Met and Trp substitutions were not included is theoretically less than 0.2%. Therefore, it appears that Arg may be the best residue in this position on the light chain.

To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the modification of antibody genes by recombination PCR. Single-amino-acid substitution by this method demonstrated the feasibility of improving the affinity of the original human Fab. Further studies on modification of other residues in CDR3, including residues that contact the antigen, will contribute to improve the affinity of the human antibody and thereby improve its utility for diagnosis and immunoprophylaxis.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. A. Petri, Jr., for generously supplying the recombinant lectin.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science and grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. X.-J.C. is a recipient of the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science Postdoctoral Fellowship for Foreign Researchers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheng, X. J., S. Ihara, M. Takekoshi, and H. Tachibana. 2000. Entamoeba histolytica: bacterial expression of a human monoclonal antibody which inhibits in vitro adherence of trophozoites. Exp. Parasitol. 96:52-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamond, L. S., D. R. Harlow, and C. C. Cunnick. 1978. A new medium for the axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica and other Entamoeba. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 72:431-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong, L., S. Chen, U. Bartsch, and M. Schachner. 2003. Generation of affinity matured scFv antibodies against mouse neural cell adhesion molecule L1 by phage display. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301:60-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujii, I. 2004. Antibody affinity maturation by random mutagenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 248:345-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall, B. L., H. Zaghouani, C. Daian, and C. A. Bona. 1992. A single amino acid mutation in CDR3 of the 3-14-9 L chain abolished expression of the IDA 10-defined idiotope and antigen binding. J. Immunol. 149:1605-1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson, G., and T. T. Wu. 2004. The Kabat database and a bioinformatics example. Methods Mol. Biol. 248:11-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones, D. H., and S. C. Winistorfer. 1997. Recombination and site-directed mutagenesis using recombination PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 67:131-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson, R., and A. Larsson. 2004. Affinity measurement using surface plasmon resonance. Methods Mol. Biol. 248:389-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi, S., E. Imai, H. Tachibana, T. Fujiwara, and T. Takeuchi. 1998. Entamoeba dispar: cultivation with sterilized Crithidia fasciculata. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 45:3S-8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann, B. J., C. Y. Chung, J. M. Dodson, L. S. Ashley, L. L. Braga, and T. L. Snodgrass. 1993. Neutralizing monoclonal antibody epitopes of the Entamoeba histolytica galactose adhesin map to the cysteine-rich extracellular domain of the 170-kilodalton subunit. Infect. Immun. 61:1772-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petri, W. A., Jr., R. Haque, and B. J. Mann. 2002. The bittersweet interface of parasite and host: lectin-carbohydrate interactions during human invasion by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:39-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharon, J. 1990. Structural correlates of high antibody affinity: three engineered amino acid substitutions can increase the affinity of an anti-p-azophenylarsonate antibody 200-fold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4814-4817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tachibana, H., X. J. Cheng, K. Watanabe, M. Takekoshi, F. Maeda, S. Aotsuka, Y. Kaneda, T. Takeuchi, and S. Ihara. 1999. Preparation of recombinant human monoclonal antibody Fab fragments specific for Entamoeba histolytica. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6:383-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tachibana, H., S. Kobayashi, Y. Kato, K. Nagakura, Y. Kaneda, and T. Takeuchi. 1990. Identification of a pathogenic isolate-specific 30,000-Mr antigen of Entamoeba histolytica by using a monoclonal antibody. Infect. Immun. 58:955-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tachibana, H., M. Takekoshi, X. J. Cheng, Y. Nakata, T. Takeuchi, and S. Ihara. 2004. Bacterial expression of a human monoclonal antibody-alkaline phosphatase conjugate specific for Entamoeba histolytica. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 11:216-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tachibana, H., K. Watanabe, X. J. Cheng, H. Tsukamoto, Y. Kaneda, T. Takeuchi, S. Ihara, and W. A. Petri, Jr. 2003. VH3 gene usage in neutralizing human antibodies specific for the Entamoeba histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin heavy subunit. Infect. Immun. 71:4313-4319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh, J. A. 1986. Problems in recognition and diagnosis of amebiasis: estimation of the global magnitude of morbidity and mortality. Rev. Infect. Dis. 8:228-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winkler, K., A. Kramer, G. Kuttner, M. Seifert, C. Scholz, H. Wessner, J. Schneider-Mergener, and W. Hohne. 2000. Changing the antigen binding specificity by single point mutations of an anti-p24 (HIV-1) antibody. J. Immunol. 165:4505-4514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu, T. T., and E. A. Kabat. 1970. An analysis of the sequences of the variable regions of Bence Jones proteins and myeloma light chains and their implications for antibody complementarity. J. Exp. Med. 132:211-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]