Abstract

The Arabidopsis tandem-pore K+ (TPK) channels displaying four transmembrane domains and two pore regions share structural homologies with their animal counterparts of the KCNK family. In contrast to the Shaker-like Arabidopsis channels (six transmembrane domains/one pore region), the functional properties and the biological role of plant TPK channels have not been elucidated yet. Here, we show that AtTPK4 (KCO4) localizes to the plasma membrane and is predominantly expressed in pollen. AtTPK4 (KCO4) resembles the electrical properties of a voltage-independent K+ channel after expression in Xenopus oocytes and yeast. Hyperpolarizing as well as depolarizing membrane voltages elicited instantaneous K+ currents, which were blocked by extracellular calcium and cytoplasmic protons. Functional complementation assays using a K+ transport-deficient yeast confirmed the biophysical and pharmacological properties of the AtTPK4 channel. The features of AtTPK4 point toward a role in potassium homeostasis and membrane voltage control of the growing pollen tube. Thus, AtTPK4 represents a member of plant tandem-pore-K+ channels, resembling the characteristics of its animal counterparts as well as plant-specific features with respect to modulation of channel activity by acidosis and calcium.

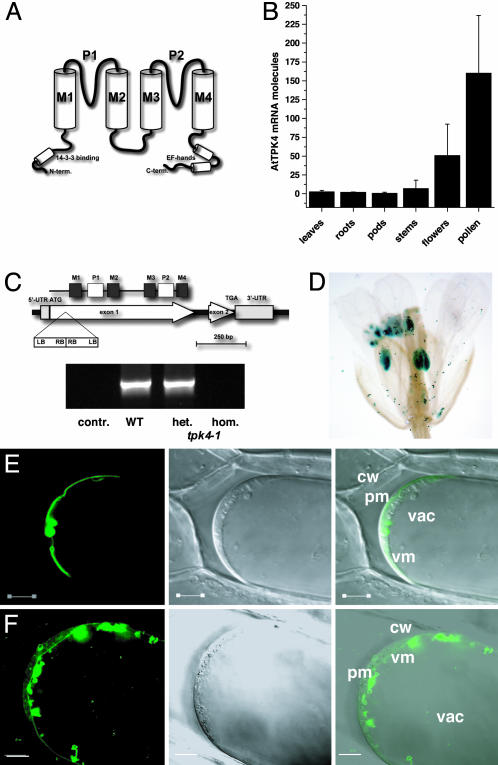

The Arabidopsis genome encodes five K+ channels, which can be assigned to a structurally uniform family exhibiting four transmembrane domains and two pore regions in tandem (Fig. 1 A and C). Based on sequence homology, these Arabidopsis tandem-pore K+ (TPK) channels, as well as the Kir-like K+ channel (KCO3), were initially combined in a single protein family of AtKCO1-like plant potassium channels (KCOs; ref. 1). In contrast to the well characterized Shaker-like Arabidopsis channels, the functional properties and the biological role of the TPK channels remain elusive. The functional analysis of the AtTPK4 (KCO4) protein presented here, however, indicates that plant tandem-pore K+ channels cannot uniformly be classified as outward rectifiers (1, 2). We therefore suggest renaming the KCO family to TPK family. Among the TPK channels, AtTPK1 (KCO1), AtTPK2 (KCO2), and AtTPK3 (KCO6) are characterized by the presence of one or two EF hands localized in the C-terminal domains of the respective channel proteins (Fig. 1 A and Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These domains are thought to be involved in Ca2+ regulation of the AtTPK1 channel (3), a feature that distinguishes them from their animal relatives of the KCNK family (4, 5). In contrast, AtTPK4 (KCO4) lacks EF hands, and the AtTPK5 (KCO5) sequence exhibits only weak similarity to the EF-consensus motif, suggesting that direct regulation of these channels by cytoplasmic Ca2+ is rather unlikely.

Fig. 1.

Expression and localization of AtTPK4. (A) Proposed topology of the tandem-pore K+ channels. According to the ARAMEMNON database (25), four transmembranes (M1-M4) and two pore regions (P1 and P2) are predicted for Arabidopsis TPKs. (B) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR on cDNA, derived from tissues indicated, revealed pronounced mRNA abundance of AtTPK4 transcripts in Arabidopsis flowers. Among the flower organs tested (not shown), pollen exhibited highest AtTPK4 expression. Data represent mean values of n ≥ 3 ± SD. (C) Identification of a T-DNA insertion mutant for AtTPK4. Schematic view of the T-DNA insertion in tpk4-1 (SALK 000212) and RT-PCR data obtained on pollen mRNA by using AtTPK4 full-length primers. contr., without reverse transcriptase; het., heterozygous plant; hom., homozygous plant. (D) Promoter-GUS staining of transgenic T2 plants revealed AtTPK4 expression in pollen. (E and F) Transient expression of AtTPK4::mgfp4 (E) and AtTPK1::mgfp4 (F) fusion proteins in onion epidermal cells. Cells were plasmolyzed with 0.5 M KNO3 and investigated. Laser-scanning image of GFP fluorescence (Left), transmitted light (Center), and overlay of both images (Right). Cw, cell wall; pm, plasma membrane; vm, vacuolar membrane; vac, vacuole. (Scale bars: 10 μm.)

We here show that the Arabidopsis TPK4 channel, besides its structural homologies (Fig. 1 A), shares functional properties with members of the animal potassium channels of the KCNK family (5). AtTPK4 expression was observed predominantly in pollen, and electrophysiological recordings on growing pollen tubes of WT and tpk4-1 mutant plants identified AtTPK4 as a contributor to the K+ conductance of the pollen tube plasma membrane.

Methods

Plant and Growth Conditions. Arabidopsis thaliana cv. Col-0 WT and transgenic plants were grown in half-concentrated Murashige and Skoog medium or in soil (for details and the generation of an AtTPK4-GUS fusion construct and the identification of an AtTPK4 mutant, see Supporting Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

RT-PCR Experiments. RT-PCR was performed on mRNA isolated from various Arabidopsis tissues essentially as described in ref. 6 (for details, see Supporting Methods).

Functional Analysis in Xenopus Oocytes. AtTPK4 cRNA was prepared by using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE RNA Transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Oocyte preparation and cRNA injection have been described elsewhere (7) (for details, see Supporting Methods).

Yeast-Based Growth Assay and Electrophysiology. For functional expression in the K+ transport-deficient yeast mutant PLY246, AtTPK4 was cloned into the pFL61 Escherichia coli-yeast shuttle vector. The basic procedures for transforming and growing of yeast cells, as well as for yeast protoplast isolation for patch-clamp analyses, were as described in ref. 8 (for details, see Supporting Methods).

Pollen Electrophysiology. Electrophysiological recordings were performed on pollen tubes of A. thaliana cv. Col-O and a tpk4-1 T-DNA [portion of the Ti (tumor-inducing) plasmid that is transferred to plant cells] insertion line. Pollen from mature flowers were directly dipped onto agar plates containing pollen germination medium as described in ref. 9 complemented with 1 mM KCl (for details, see Supporting Methods).

Localization Studies. To localize AtTPK4 and AtTPK1, the respective cDNAs were cloned into pPILY (10), and stop codons were mutated by site-directed mutagenesis. The mgfp4 coding cDNA was inserted 3′ and in frame with the channel cDNAs to gain plasmids 2x35S:AtTPK4::mgfp4 and 2x35S:AtTPK1::mgfp4, respectively. Plasmids carrying either construct were transiently expressed in onion epidermis cells by using a helium-driven particle inflow gun.

Results

Members of the Arabidopsis TPK family (AtTPK1 to -5) share a common topology and exhibit a predicted 14-3-3 binding motif at their amino terminus, together with a putative Ca2+-binding domain at their carboxyl terminus (Fig. 1 A). AtTPK4 represents a structurally unique member within this family because it lacks both regulatory sites (see Fig. 7). To gain insights into the biological function of AtTPK4, we localized and functionally expressed this Arabidopsis channel and characterized a corresponding knockout mutant.

AtTPK4 Is Expressed in Pollen and Localizes to the Plasma Membrane. A combination of RT-PCR and RACE techniques were used to amplify the predicted AtTPK4 cDNA from flowers. By using quantitative real-time RT-PCR, very low transcript numbers (close to the resolution limit of this method) were detected in leaves, roots, pods, and stems (Fig. 1B). Flowers in general, and pollen in particular, however, represented the sites of highest AtTPK4 mRNA abundance. In addition, pollen express the Shaker-like inward rectifiers AKT1 and AKT6 (11), as well as the so far uncharacterized AKT5 channel. Both Arabidopsis K+-efflux channels, the root stelar outward rectifier stelar K+ outward rectifier (SKOR) (12) and the guard cell outward rectifier guard cell outward rectifying K+ channel (GORK) (13), were found to be expressed in pollen, too (data not shown). In addition to AtTPK4, all other members of the TPK family are expressed in flowers (data not shown). To study the cellular specificity of AtTPK4 promoter activity throughout plant development, a 5′ upstream sequence of the AtTPK4 gene was translationally fused to the E. coli β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene and transferred to the nuclear genome of A. thaliana. Transgenic plants harboring the fusion construct AtTPK4:GUS exhibited GUS activity in root tips (5 of 20 lines), hypocotyls (2 of 20 lines), and pollen grains (all lines; Fig. 1D and see Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

When AtTPK4 was transiently expressed, as a translational fusion with the GFP in onion epidermal cells, 24 h after ballistic bombardment AtTPK4::GFP was localized to the plasma membrane, as well as in compartments of the secretory pathway (Fig. 1E). In contrast to AtTPK4, AtTPK1 was localized at the vacuolar membrane (Fig. 1F; cf. refs. 14 and 15).

AtTPK4 Mutants Exhibit Altered Electrical Plasma Membrane Properties. To elucidate the physiological role of AtTPK4, we isolated a homozygous T-DNA insertion line (SALK 000212; tpk4-1). In tpk4-1 mutants, the T-DNA insertion site was verified by sequencing to be 72 bp downstream of the ATG start codon (Fig. 1C). Remarkably, the T-DNA was inserted twice with left-border sequences oriented toward the AtTPK4 gene. As a result of the insertion, AtTPK4 transcripts were not detectable in tpk4-1 homozygous plants, indicating a knockout situation (Fig. 1C). According to the expression of AtTPK4 in pollen, and possibly hypocotyls and root tips, tpk4-1 plants were analyzed for phenotypic changes in a number of growth assays. No impairment of pollen germination rate and growth, as well as hypocotyl or root growth, was detectable in knockout plants (data not shown).

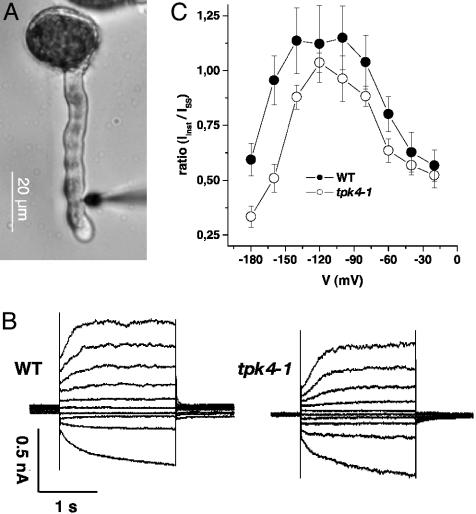

Using the double-barreled impalement technique, we characterized the electrophysiological properties of WT and mutant pollen tubes in more detail (Fig. 2). When impaling intact pollen tubes derived from WT plants, we found the electrical properties of the pollen tube plasma membrane to be dominated by three major conductances. At depolarizing membrane voltages, slowly activating, voltage-dependent, outward-rectifying currents were activated, whereas hyperpolarizing voltage pulses elicited time- and voltage-dependent inward currents. In addition, an instantaneously activating, voltage-independent conductance superimposed the two rectifiers (Fig. 2B Left). This instantaneous current, however, was significantly reduced in pollen tubes of the tpk4-1 mutant (Fig. 2B Right). Thus, the ratio of the instantaneous and time-dependent currents between -180 to -20 mV was lower in tpk4-1 than in WT plants (Fig. 2C). This finding indicates that AtTPK4 contributes to the voltage-independent background currents of the pollen tube plasma membrane (cf. ref. 16).

Fig. 2.

Pollen tube membrane voltage recordings. (A) Pollen tubes growing on agar plates were impaled with double-barreled electrodes at or below the emerging tip. (B) Voltage-clamp recordings from pollen tubes of WT plants (Left) and the tpk4-1 mutant (Right). The plasma membrane was clamped from a holding voltage of -100 mV stepwise to test voltages ranging from -180 to 0 mV. (C) Relative contribution of instantaneous currents (Iinst, sampled 30-50 ms after start of the test voltage) to the steady state currents (ISS). Data points represent mean ± SE, n ≥ 7.

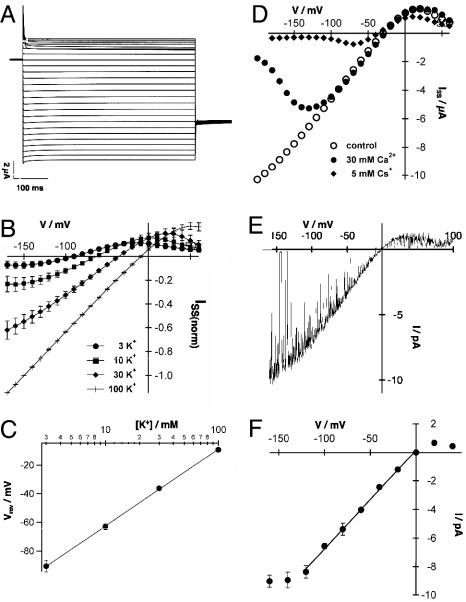

AtTPK4 Is a K+-Selective “Open Rectifier.” To gain insights into the biophysical properties of AtTPK4, this two-pore channel was functionally expressed in Xenopus oocytes and analyzed by using the two-electrode voltage-clamp technique. After pulses to hyperpolarizing and depolarizing voltages, instantaneous, K+-selective currents were recorded (Fig. 3 A, B, D, and E). The current-voltage (I-V) curve showed a strong asymmetry under nearly symmetrical K+ concentrations (100 mM K+ outside), with ohmic behavior at voltages negative to the potassium reversal voltage (EK) (Fig. 3 B, D, and E). Positive to EK, saturation followed by a negative slope conductance was observed. The oocyte plasma membrane showed nearly Nernstian voltage shifts upon changes in external K+ concentrations (Fig. 3 B and C), with a shift of 62.5 ± 2.2 mV per 10-fold change in external K+ concentration (Fig. 3C). In accordance with the properties of a K+-selective channel, the relative permeability of AtTPK4 for monovalent cations was  (mean ± SE, n = 3). AtTPK4-mediated inward currents were almost completely blocked by 5 mM external Cs+, whereas a voltage-dependent block of the inward currents at high external Ca2+ (30 mM) became evident at voltages more negative than -100 mV (Fig. 3D). In cell-attached as well as inside-out patches from AtTPK4-expressing oocytes, single 68- to 70-pS channels could be resolved (cf. Figs. 3E and 5C). The open channel I-V curve of a single AtTPK4 channel showed an asymmetrical shape very similar to that of the whole-cell I-V curve, indicating that the weak inward rectification results from a fast open channel block (Fig. 3E), rather than from a lower open probability (Po) at positive voltages. Single-channel properties in response to voltage steps and ramps were in agreement with the macroscopic AtTPK4 currents (compare Fig. 3 B with E and F).

(mean ± SE, n = 3). AtTPK4-mediated inward currents were almost completely blocked by 5 mM external Cs+, whereas a voltage-dependent block of the inward currents at high external Ca2+ (30 mM) became evident at voltages more negative than -100 mV (Fig. 3D). In cell-attached as well as inside-out patches from AtTPK4-expressing oocytes, single 68- to 70-pS channels could be resolved (cf. Figs. 3E and 5C). The open channel I-V curve of a single AtTPK4 channel showed an asymmetrical shape very similar to that of the whole-cell I-V curve, indicating that the weak inward rectification results from a fast open channel block (Fig. 3E), rather than from a lower open probability (Po) at positive voltages. Single-channel properties in response to voltage steps and ramps were in agreement with the macroscopic AtTPK4 currents (compare Fig. 3 B with E and F).

Fig. 3.

Biophysical properties of AtTPK4 in Xenopus oocytes. (A) Whole-cell currents of AtTPK4-expressing oocytes in response to 10-mV voltage steps from +60 to -200 mV perfused with the standard solution containing 30 mM KCl, 70 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Mes/Tris (pH 5.6). (B) I-V relationship of AtTPK4-mediated steady-state currents at varying external K+ concentrations. External solutions were composed of the indicated K+ concentrations, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Mes/Tris (pH 5.6). NaCl was used to maintain the ionic strength. Currents were normalized to -150 mV in the 100-mM KCl solution. Data points represent mean ± SD, n = 4. Note the deviation from linearity at positive membrane voltages. (C) K+ selectivity of AtTPK4-mediated currents was obtained from the reversal voltages in B, and a slope of 62.5 ± 2.2 mV for a 10-fold change in external K+ concentration was calculated. (D) Voltage-dependent block of AtTPK4 currents by Cs+ and Ca2+ as indicated. The solutions were composed of 30 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Tris/Mes (pH 7.5). (E) I-V relation of single channels during a 1,000-ms voltage ramp from +100 to -160 mV, starting from a holding voltage of 0 mV. Recordings were performed in the cell-attached mode of the patch-clamp technique in the presence of 100 mM KCl and 10 mM Mes/Tris (pH 5.6) in the pipette and bath solution. (F) I-V plot of single channel recordings of AtTPK4. Slope conductances were determined between -120 and 0 mV to be 68.7 ± 4 pS (mean ± SD, n = 4). Solutions and configuration were as in E.

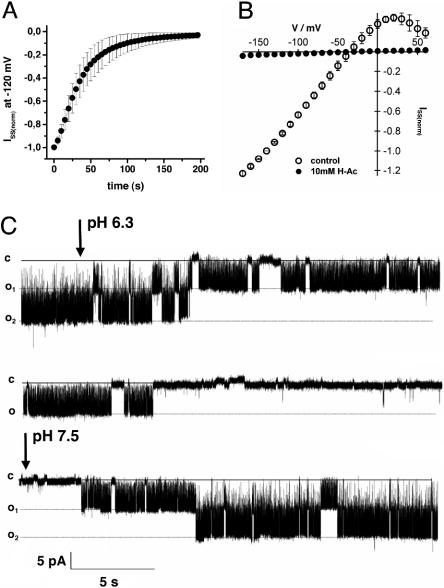

Fig. 5.

Acidosis-mediated inhibition of AtTPK4 currents. (A) Time-dependent inhibition of AtTPK4-mediated whole-cell currents in oocytes after cytoplasmic acidification by bath perfusion with 10 mM sodium acetate. Shown are normalized steady-state currents at -120 mV. The bath solution was composed of 30 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM sodiumacetate, and 10 mM Mes/Tris (pH 5.6). (B) The I-V analysis of AtTPK4-mediated steady-state currents in response to bath perfusion with sodium acetate reveals the acidosis-mediated inhibition of AtTPK4 currents. Data points represent mean ± SD, n = 3. Steady-state currents were normalized to -140 mV in the absence of sodium-acetate. Control solution was 30 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Mes/Tris (pH 5.6). (C) Single-channel recordings in the inside-out configuration at -100 mV at pH 7.5 and pH 6.3 show the reduction in channel open probability (Po). Bath perfusion with the solution at pH 6.3 starts after the first arrow. Recovery in the bath solution at pH 7.5 is shown after the second arrow. Bath solution was composed of 100 mM KCl and 10 mM Tris/Mes (pH 7.5) or 10 mM Mes/Tris (pH 6.3). The pipette solution contained 100 mM KCl and 10 mM Tris/Mes (pH 7.5).

AtTPK4 Complements Growth of a Yeast Mutant. To further elucidate the physiological role of AtTPK4, we expressed this channel in a K+ transport-deficient mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (17). In accordance with a plasma membrane-localized K+ channel, growth assays under K+-limiting conditions demonstrated the capability of AtTPK4 to complement growth of the yeast mutant (Fig. 4A). After yeast growth at different external calcium concentrations, we found AtTPK4-mediated growth rescue at 100 μM potassium when calcium concentration was low (200 μM). At 5 mM calcium in the medium, yeast growth was inhibited already at 10 times higher potassium supply (1 mM) (Fig. 4A). Patch-clamp analyses of AtTPK4-expressing yeast cells (Fig. 4 B and C) confirmed the electrophysiological properties of this K+ channel recognized in Xenopus oocytes. Single-channel recordings on AtTPK4-expressing yeast allowed us to deduce a slope conductance of 77 pS (195/150 mM KCl; Fig. 4C and Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The time-averaged I-V relationship exhibited the typical features of an open rectifier (Fig. 4B). These data clearly demonstrate that, in both eukaryotic expression systems, Xenopus oocytes and yeast cells, the AtTPK4 channel is translocated to the plasma membrane. It should be noted that AtTPK1 failed to restore growth of the K+ transport-deficient yeast mutant (Fig. 4A). AtTPK1 translationally fused to GFP associated with the vacuolar membrane of yeast cells only (data not shown), consistent with its targeting in plant cells (14, 15).

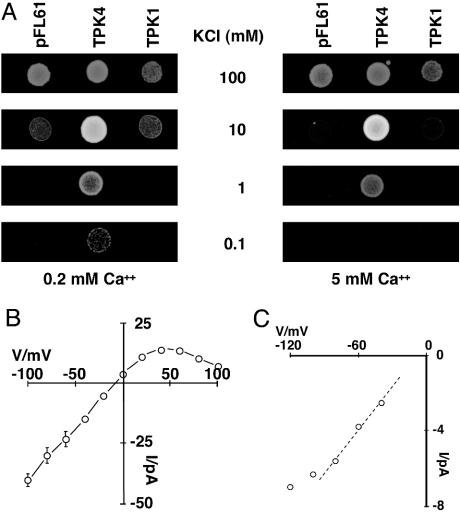

Fig. 4.

Functional analysis of AtTPK4 in yeast. (A) AtTPK4 complements the potassium-dependent growth defect of the Δtrk1trk2tok1 triple deletion mutant (17). Yeast triple deletions transformed with the empty pFL61 plasmid or with the pFL61 plasmid carrying either the AtTPK4 or the AtTPK1 gene, respectively. Although all strains grew perfectly well in 100 mM KCl at low (0.2 mM, Left) and high (5 mM, Right)Ca2+, mutants harboring the empty plasmid or expressing the vacuolar channel AtTPK1 did not grow at lower KCl concentrations. In contrast, AtTPK4-expressing mutants were able to restore yeast growth even at submillimolar K+ concentrations when calcium was low (0.2 mM), whereas, in the presence of high calcium (5 mM), AtTPK4-expressing yeast mutants exhibited a K+- and Ca2+-dependent growth phenotype. (B) Time-averaged electrical currents recorded from the plasmalemma of AtTPK4-expressing yeast cells. Current recordings were performed in the outside-out configuration, and the mean currents of 2.5-s traces, corrected for a 200-pS leak, are plotted vs. the applied membrane voltage. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3; see Fig. 9). (C) From the I-V plot, a maximum open channel conductance of 77 pS could be determined between -40 mV and -80 mV (dotted linear regression line). Solutions in B and C were as indicated in Methods.

AtTPK4 Is Sensitive to Acidosis. Modulation of animal TPK channels has been shown to be mediated by various stimuli, such as mechanical stress and temperature, or protons (5, 18). In contrast to plant Shaker-like channels and members of the animal tandem-pore K+ channels of the tandem-pore acid-sensing K+ channel (TASK) family (5). Arabidopsis AtTPK4 was not sensitive to changes in extracellular pH. Cytoplasmic acidosis in AtTPK4-expressing oocytes in response to acetate treatment, however, suppressed AtTPK4-mediated whole-cell currents completely (Fig. 5 A and B), a behavior that distinguishes the Arabidopsis channel from, e.g., TWIK-related K+ channel (TREK)-1, an acid-activated K+ channel (19). The mechanism of acid-mediated current reduction was analyzed during pH changes from pH 7.5 to 6.3 at the cytoplasmic side of an inside-out patch (Fig. 5C). Although the open-channel current amplitudes did not change during bath perfusion with buffers of different pH, cytosolic acidification drastically reduced the open probability of AtTPK4. Thus, the reversible modulation of channel activity by cytoplasmic protons points to an intrinsic pH sensor in the AtTPK4 channel, a feature reminiscent of the human two-pore channels two P domain weak inwardly rectifying K+ channel (TWIK)-1 and TWIK-2 (20, 21) and of the yeast two-pore channel two P domain outwardly rectifying K+ channel (TOK) 1 (22).

To test the mechano-sensitivity of the AtTPK4 channel, we coexpressed AtTPK4 with the Samanea aquaporin SSAQP2 (23) and applied osmotic stress. Unlike TWIK-related K+ channel (TREK)-1 (19), AtTPK4 was only moderately sensitive to membrane stretch (oocyte swelling). Hypoosmotic steps from 400 to 70 mosmol increased AtTPK4-mediated whole-cell inward currents in Xenopus oocytes up to 30% in a reversible manner (data not shown). Like TREK-1, AtTPK4 was heat-activated (Fig. 6), and, from an Arrhenius-plot of the maximal chord conductance, a Q10 of 3.6 for temperatures >20°C and a Q10 of 1.7 for temperatures <20°C could be determined (see Fig. 10, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These data implicate future studies toward the mechano- and temperature dependence of WT and mutant pollen tube growth.

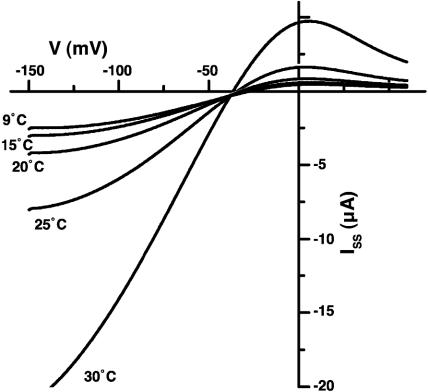

Fig. 6.

AtTPK4 activation by heat. Whole-cell currents of AtTPK4-expressing oocytes recorded at different temperatures. The I-V curves were obtained by a -150-mV voltage pulse for 100 ms followed by a 700-ms voltage ramp from -150 to +60 mV.

Discussion

The fast, polar growth of pollen tubes is accomplished by continuous trafficking and fusion of membrane vesicles to the growing tip. Growth rates strongly depend on the steepness of a calcium gradient originating at the pollen tube tip. Tube growth occurs in a pulsatile manner, reflected by oscillatory concentration changes in Ca2+, Cl-, K+, and protons (24). In line with previous patch-clamp recordings on pollen protoplasts, our impalement studies revealed inward and outward K+ fluxes to be dominated by time- and voltage-dependent, slowly activating currents, probably mediated by SPIK (11) and guard cell outward rectifying K+ channel (GORK)/stelar K+ outward rectifier (SKOR), respectively. The latter two channels may serve as components of an osmotic valve, allowing fine tuning of turgor to prevent rupture of the fragile pollen tube tip. Disruption of SPIK resulted in the loss of a time-dependent, inward-rectifying K+ conductance in the plasma membrane of spik-1 pollen tubes (11). Spik-1 pollen still germinate and exhibit tube growth, although largely reduced when compared with WT. The residual K+-dependent germination and pollen development in the spik-1 mutant is very likely accomplished by instantaneously activating K+-permeable background channels (11, 16). These channels contributed to the inward K+ current of this cell type by at least 30%, and the electrophysiological properties of this weakly rectifying K+ channel were reminiscent of those of AtTPK4 reported here. In addition, an AtTPK4-related, spontaneously activating K+-channel with a single channel conductance of ≈70 pS has just been characterized in lily pollen (16). Consistent with these observations, we found highest expression levels of the plasma membrane-localized channel AtTPK4 in transgenic plants expressing an AtTPK4 promoter GUS fusion, as well as by quantitative RT-PCR in protoplasts derived from Arabidopsis pollen. In the tpk4-1 mutant, this instantaneous current was significantly reduced, although not absent completely. This result indicates that additional conductances contribute to the ionic fluxes at the pollen tube plasma membrane (16).

Here, we have shown that Arabidopsis pollen express a spontaneously activating, background K+ conductance encoded by the AtTPK4 gene in addition to voltage-dependent K+ efflux and uptake channels. Like its animal relatives of the KCNK family (5), AtTPK4 is a plasma membrane-localized, instantaneously activating, K+-selective channel when expressed in both Xenopus oocytes and yeast. AtTPK4 is sensitive to extracellular Ca2+ but is insensitive toward changes in extracellular pH. In contrast, AtTPK4 is efficiently blocked by cytosolic acidification.

Pollen tube growth and guidance along the transmitting tract toward the ovary represent Ca2+- and pH-regulated processes. Thereby, the extracellular calcium concentration controls the growth direction whereas oscillating cytoplasmic calcium, the calcium gradient, and proton concentrations feed back on the growth rate. The pollen K+ uptake channel AKT6 (SPIK1) is sensitive to external pH changes, but insensitive toward extracellular Ca2+ (11). AtTPK4, however, is modulated by external Ca2+ and cytoplasmic protons. Due to its weak voltage dependence, AtTPK4 is active at membrane voltages positive to -100 mV, a voltage range where SPIK1 is closed, and thus capable of stabilizing the membrane voltage over a broad voltage range. The immediate closure of AtTPK4 channels upon cytoplasmic acidosis in distinct regions (tip vs. clearing zone) of the growing pollen tubes would diminish the background K+ conductance and in turn increase the susceptibility of the plasma membrane toward depolarization, resulting from activation of calcium channels. Thus, the complementary voltage-, pH-, and Ca2+-dependent properties of the two K+-channels may account for the K+-dependent pollen physiology. AtTPK4 represents a plant tandem-pore plasma membrane K+ channel, and our findings strongly suggest that this open rectifier provides for a background K+ conductance observed in pollen protoplasts. On the basis of multiple K+ channel mutants, future studies should allow us to dissect the potassium fluxes at the molecular level and to elucidate their role during pollen tube growth and/or guidance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The mechanical part and the Peltier device for the temperature measurements were built by G. Gaggero, D. Magliozzi, and E. Gaggero (with the valuable advice of F. Conti). We gratefully acknowledge the help of P. Ache and S. Michel for the LightCycler experiments and the assistance of H. Merkel in confocal microscopy. We thank C. Koncz (Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research, Cologne, Germany) for generous supply of the pPILY plasmid. The help of E. Jeworutzki during pH measurements is gratefully acknowledged. We thank the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory and the Syngenta Arabidopsis Insertion Library for providing the sequence-indexed Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SPP1108 (to A.B., K.C., and R.H.). A.C. was funded by a guest-scientist stipend of the Sonderforschungsbereich 487, Würzburg and by a research fellowship of the Von Humboldt Foundation.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: I-V, current-voltage; TPK, tandem-pore K+; GUS, β-glucuronidase; T-DNA, portion of the Ti (tumor-inducing) plasmid that is transferred to plant cells; SPIK, Shaker-like pollen inwardly rectifying K+ channel.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AY258073).

References

- 1.Czempinski, K., Zimmermann, S., Ehrhardt, T. & Mueller-Roeber, B. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 2565-2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czempinski, K., Zimmermann, S., Ehrhardt, T. & Mueller-Roeber, B. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 6896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Very, A. A. & Sentenac, H. (2002) Trends Plant Sci. 7, 168-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derst, C. & Karschin, A. (1998) J. Exp. Biol. 201, 2791-2799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein, S. A., Bockenhauer, D., O'Kelly, I. & Zilberberg, N. (2001) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 175-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szyroki, A., Ivashikina, N., Dietrich, P., Roelfsema, M. R., Ache, P., Reintanz, B., Deeken, R., Godde, M., Felle, H., Steinmeyer, R., et al. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 2917-2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker, D., Dreyer, I., Hoth, S., Reid, J. D., Busch, H., Lehnen, M., Palme, K. & Hedrich, R. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 8123-8128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertl, A., Bihler, H., Kettner, C. & Slayman, C. L. (1998) Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 436, 999-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreiber, D. N. & Dresselhaus, T. (2003) Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 21, 319. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrando, A., Farras, R., Jasik, J., Schell, J. & Koncz, C. (2000) Plant J. 22, 553-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouline, K., Very, A. A., Gaymard, F., Boucherez, J., Pilot, G., Devic, M., Bouchez, D., Thibaud, J. B. & Sentenac, H. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 339-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaymard, F., Pilot, G., Lacombe, B., Bouchez, D., Bruneau, D., Boucherez, J., Michaux-Ferriere, N., Thibaud, J. B. & Sentenac, H. (1998) Cell 94, 647-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ache, P., Becker, D., Ivashikina, N., Dietrich, P., Roelfsema, M. R. & Hedrich, R. (2000) FEBS Lett. 486, 93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czempinski, K., Frachisse, J. M., Maurel, C., Barbier-Brygoo, H. & Mueller-Roeber, B. (2002) Plant J. 29, 809-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenknecht, G., Spoormaker, P., Steinmeyer, R., Brueggeman, L., Ache, P., Dutta, R., Reintanz, B., Godde, M., Hedrich, R. & Palme, K. (2002) FEBS Lett. 511, 28-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutta, R. & Robinson, K. R. (2004) Plant Physiol. 135, 1398-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertl, A., Ramos, J., Ludwig, J., Lichtenberg-Frate, H., Reid, J., Bihler, H., Calero, F., Martinez, P. & Ljungdahl, P. O. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 47, 767-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel, A. J. & Honore, E. (2001) Trends Neurosci. 24, 339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maingret, F., Patel, A. J., Lesage, F., Lazdunski, M. & Honore, E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26691-26696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chavez, R. A., Gray, A. T., Zhao, B. B., Kindler, C. H., Mazurek, M. J., Mehta, Y., Forsayeth, J. R. & Yost, C. S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 7887-7892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesage, F., Guillemare, E., Fink, M., Duprat, F., Lazdunski, M., Romey, G. & Barhanin, J. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 1004-1011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertl, A., Bihler, H., Reid, J. D., Kettner, C. & Slayman, C. L. (1998) J. Membr. Biol. 162, 67-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moshelion, M., Becker, D., Biela, A., Uehlein, N., Hedrich, R., Otto, B., Levi, H., Moran, N. & Kaldenhoff, R. (2002) Plant Cell 14, 727-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feijo, J. A., Sainhas, J., Holdaway-Clarke, T., Cordeiro, M. S., Kunkel, J. G. & Hepler, P. K. (2001) Bioessays 23, 86-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwacke, R., Schneider, A., van der, G. E., Fischer, K., Catoni, E., Desimone, M., Frommer, W. B., Fluegge, U. I. & Kunze, R. (2003) Plant Physiol. 131, 16-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.