Abstract

CONTEXT:

Inimitable among the trio of recommended immunizations administered to newborns at delivery centers of institutions is hepatitis B. While it is necessary for hepatitis B to be given within 24 hours of birth, the same cannot be said for Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) and zero-dose oral polio vaccine (OPV).

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the impact of rescheduling of BCG vaccination from the current twice weekly to daily to cover newborn vaccinations at the Government Medical College, Patiala, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Until 2015, the delivery of BCG vaccine was restricted to twice a week, but from the year 2015, the schedule was changed from twice weekly to daily. Records for the 2 years, 2014 and 2015, were obtained, i.e., before and after the change. Data on 7065 babies born from January 2014 to December 2015 were statistically analyzed for the coverage of birth dose of hepatitis B, BCG, and OPV using Microsoft Excel. Chi-square test was applied, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS:

Rescheduling of BCG dose, from twice weekly to daily, the coverage of BCG and OPV zero dose increased from 54% (in 2014) to 78% (in 2015), and a marked increase from 8.2% to 42.9% was noted for the birth dose of hepatitis B. By rescheduling BCG (twice weekly to daily), the vaccine wastage increased from 21.5% to 26.2%, the difference found to be statistically insignificant.

CONCLUSIONS:

Modification in the delivery of immunization service from twice a week to daily has had a good impact on the vaccination of newborns though the goal of achieving the ideal 100% coverage is yet to be reached. Apart from the immunization of newborns, improving parental awareness, better coordination between immunization staff and maternal health staff, improved communication, and clear delineation of responsibility and answerability in the immunization service delivery will have a good impact on the vaccination of newborns.

Key words: Bacillus Calmette–Guérin, hepatitis B birth dose, oral polio vaccine, timely vaccination, universal immunization program, vaccine wastage

Introduction

Childhood immunization has been shown to be among the most cost-effective interventions in health-care delivery.[1] Significant gains have been made through vaccinations, resulting in a reduction of both morbidity and mortality outcomes of infectious diseases. Over 2 million deaths are averted each year globally by immunization.[2]

Routine universal childhood immunization is given free of cost in India.[3] The timely administration of recommended vaccines poses a major challenge to achieving the core objective of vaccination programs, which is to prevent occurrence of diseases.[4] However, the coverage of vaccination remains uneven in the country as a result of operational challenges. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the administration of three vaccines, namely, oral polio vaccine (OPV), Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), and hepatitis B vaccine as early as possible after birth.[5]

OPV is given at birth to increase the level of poliovirus neutralizing antibodies and seroconversion rates resulting from subsequent doses of the polio vaccine as well as induce mucosal protection.[6] BCG has a positive role in the prevention of tubercular meningitis and miliary (disseminated) tuberculosis in infants and young children.[7]

Hepatitis B vaccine was introduced into the universal immunization program (UIP) of 2007-2008 in a phased manner across different states of the country.[8] The birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine is given as soon as possible after birth, preferably within 24 h, and is mandatory for all institutional deliveries. The reported coverage in Punjab is only 32.9% (CES 2009). Since maternal hepatitis B infection may be masked by errors in testing and reporting, the birth dose acts as a protective net.[9] The efficacy of postexposure prophylaxis declines with time after birth, so it is critically important to provide hepatitis B vaccine (single antigen) as near to birth as possible, to prevent the transmission of HBV infection from mother to child.[10] Some studies have shown that 70%–95% of infants born to hepatitis B surface antigen-positive mothers are protected with the timely birth dose, even in the absence of hepatitis B immune globulin.[11]

The WHO recommends that the number vaccinated within 24 h with hepatitis B birth dose out of the total newborns be used as a performance indicator for immunization programs. The early start of vaccination improves the completion of all other vaccines on time.[12]

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, has recommended that the “wastage rate of all vaccines should be no higher than 25% (wastage factor of 1.33).”[13] Higher vaccine wastage escalates the demand of vaccines with the avoidable rise in cost of procurement and supply of vaccines.[14] Sizable funds have been secured from the immunization budget for the purchase of vaccines, and so the assessment of vaccine wastage is vital for the forecasting of the “need estimation.” After reconstitution, freeze-dried BCG vaccine should be used within 4 h,[15] and any remaining dose in the opened vial should be discarded at the end of the session.[16]

The present study aimed to assess the impact of rescheduling of BCG vaccination from the current twice weekly to daily vaccinations of newborns at the tertiary care hospital (Rajindra Hospital) attached to Government Medical College, Patiala, Punjab, India.

Materials and Methods

Approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee was obtained, and a planned prospective study spanning two calendar years (2014 and 2015) was conducted at the immunization clinic of Rajindra Hospital. BCG was being administered on 2 days a week till 2014 while all other UIP vaccines were given on all working days. This practice was allowed to continue throughout 2014, i.e., during the first half of 2-year study period. A change was brought in so that starting from January 2015 all vaccines were given on all working days. Records for both years, i.e., before and after the intervention were obtained for analysis. Information on the number of births and use of BCG vaccine (OPV and hepatitis B-under open vial policy) for the same periods was also collected in order to study both utilization and wastage of vaccines.

Data pertaining to 7065 newborns from January 2014 to December 2015 were statistically analyzed for the coverage of birth dose of hepatitis B, BCG, and OPV using Microsoft Excel. Chi-square test was applied, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

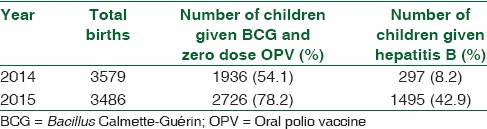

A total of 3579 live births were reported in the year 2014 (1st year of study period) at the institution. Of these, 1936 (54.1%) newborns received BCG and OPV zero dose during the sessions conducted on Wednesdays and Saturdays whereas only 297 (8.2%) newborn received hepatitis B vaccine birth dose, despite the daily availability of the vaccine at the immunization clinic.

Provision of BCG dosage on all working days, from the year 2015, increased the rate of vaccination delivery for BCG and OPV and rather markedly for hepatitis B birth dose as multiple visits were avoided, and all the three vaccines for which the newborn was eligible were provided simultaneously. Out of 3486 live births in the same year, 2726 (78.2%) newborns received BCG and OPV zero dose, and the birth dosage delivery of hepatitis B rose to a staggering level of 1495 (42.9%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

The number of children who received Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, oral polio vaccine zero dose, and hepatitis B birth dose during the study period

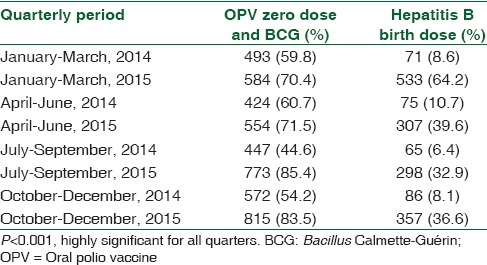

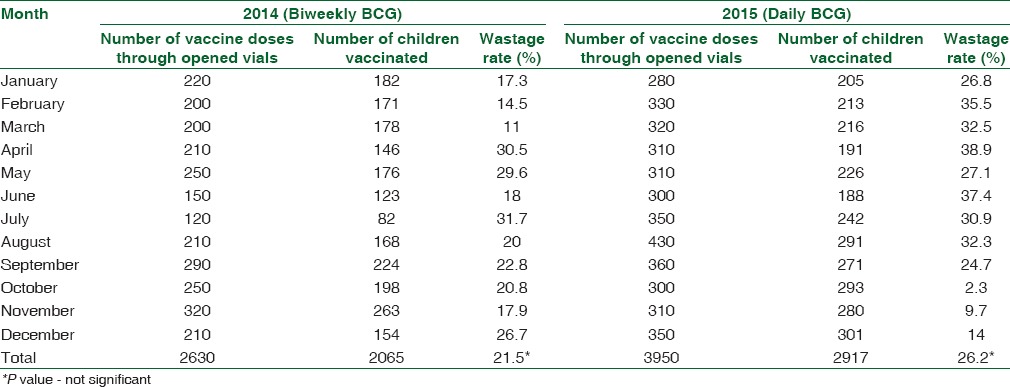

Table 2 depicts the comparison of the delivery rate of all the three vaccines in each quarter of the study period, and the result was statistically significant with a P < 0.001. The data concerning the number of BCG vaccine doses (given to babies up to age of one year) through opened vials, the number of children vaccinated, and the wastage rate are provided in Table 3. While vaccine wastage rate for the year 2014 was 21.5%, it had increased to 26.2% in the year 2015 when the BCG sessions were conducted daily. This difference in wastage rate, however, was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Comparison of quarterly data of vaccine dosage delivery during the study period

Table 3.

Wastage rate for Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine during the study period

Discussion

The fourth of the Millennium Development Goals focused on reducing child mortality. This is achievable, and India is on the road to achieving those goals with respect to improved health services for maternal and child health. With the rising trend of institutional deliveries across the country, the concerted effort for improving vaccination of newborns not only ensured the timely protection against diseases but also facilitated the early registration of health records, follow-up for routine immunization, and appropriate care during infancy and childhood.

It was evident in the current study that when the provision of immunization services for BCG were rescheduled from twice weekly to daily, the coverage of BCG and OPV zero dose increased from 54% to 78%. The surprising associated positive result was the early acceptance and sharp increase of hepatitis B birth dose delivery from 8.2% to 42.9%.

Instead of sending staff from the immunization clinic into wards for bedside immunization, parents/attendants brought the newborns to the clinic for immunization. Awareness of the importance of immunization of less well-known diseases such as hepatitis B compared to more notorious diseases such as tuberculosis may be a factor responsible in the disparity. Hepatitis B vaccination has a hidden disadvantage in that it is time bound (within 24 h of birth) whereas BCG can be administered within the first 15 days as per National Immunization Schedule. Vaccination is done during OPD periods (8.00 am to 2.00 pm). The chances of missing hepatitis B vaccine are much greater than BCG. BCG has been in the immunization schedule for many decades whereas hepatitis B was introduced into the schedule only a few years ago though it is free of cost.

The observations of the present study are in consonance with those of Gupta et al. who reported that provision of daily immunization is a better method of vaccine delivery in that it leads to a marked increase in attendance at the immunization clinic. They reported a progressive improvement over a 3-year period, 32%, 116%, and 156% from the base level.[17]

Taneja et al. studied the implementation of the newborn vaccination program in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand and observed that vaccination was conducted only during the clinic hours and not round the clock, which compromised the vaccination of newborns delivered during the nonclinic hours. In their study, ensuring that the JSY incentives (cash maternity benefit scheme for institutional deliveries in India) were released only after newborn vaccination was an important contributory factor toward increased vaccine coverage.[5] A similar observation was made in a study done in five Papua New Guinea Hospitals which reported that adequate access to appropriately stored vaccine in maternity units can improve coverage of hepatitis B birth dose.[18] A study in the Philippines reported that providing training for health workers was associated with increased coverage of hepatitis B.[19]

In the present study, it was observed that although the increase in the number of children who received timely hepatitis B birth dose was substantial, the proportion of children who received hepatitis B birth dose was still significantly lower than those who received BCG and OPV zero dose after birth. Although a decline was observed from the first quarter till the end of the year, this may have been seasonal as January–March is the most convenient for parents.

The present study observations can be extrapolated to other sites and contexts since first, there was no specific local cause in this context, and second, the increase was not marginal but notable, from 8% to 42%. Third, the chances of the use of services increased when they are available on a daily basis.

Kuruvilla and Bridgitte observed that the proportion of children who had received hepatitis B/BCG by 0 day was around 3%–11%, and BCG attained 81.3%–86.1% level by 14 days, whereas hepatitis B (50.6%–55%) continued to remain low compared to BCG.[20]

In revising the schedule from twice weekly to daily, vaccine wastage becomes an important economic aspect of immunization. Vaccine wastage can be expected in all programs, but there should be an acceptable limit to wastage.[21]

According to the WHO, projected vaccine wastage rate for lyophilized vaccines is expected to be 50% for 10–20 dose vials.[22] Higher wastage rates are acceptable in order to increase vaccine coverage in a setting where vaccine coverage is low.[14]

In a study done in a tertiary care center of Nagpur, India, BCG wastage rate was found to be much lower (22%) than the limits set by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, and WHO. They explained that the vaccine wastage may have been low because the hospital was a tertiary care center with daily vaccination sessions.[23]

In our study, BCG wastage increased from 21.5% to 26.2% with the rescheduling (twice weekly to daily), but still it was much lower than the projected data by Mehta et al. (45%),[16] Mukherjee et al. (49.3%),[24] Chinnakali et al. (70.9%),[21] and Gupta et al. (77.9%).[14]

It was observed in the current study that there was no difference in the number of target population as the total number of live births during the two study years was approximately equal. This proves that the majority of the newborns missed the vaccination at the institutions after delivery during the initial biweekly immunization times.

It is worth noting that there is no increase in cost in utilizing these daily services instead of twice a week as the staff is in full-time employment and so is available every day. BCG vaccine wastage before and after the intervention was analyzed statistically and was not found significant. Staff efficiency, operational logistics, and vaccine availability remain unaffected irrespective of twice weekly or daily regimen.

There is low to very low awareness among the parents about the relatively newer vaccines resulting in a complete disregard of the availability of the plentiful supply of free vaccine and an efficient immunization staff. The restricted hours of opening of the clinic and festive days and Sundays led to a reduced utilization of available facilities. An attempt to improve the parental awareness of the effective prevention of these preventable diseases may make the situation more encouraging. Furthermore, bedside immunization is likely to yield better results. Neonatal care should be linked to early newborn immunizations.

Obstacles such as improper logistic planning, lack of coordination between immunization staff and maternal health staff, poor communication, and the lack of a clear definition of areas of responsibility are important for achieving effective vaccination and reaching the goals set and even beyond.

Conclusions

The study conclude that the modification in the immunization service delivery made a good impact on newborn vaccination though the goal of the ideal 100% coverage is still beyond reach. The improvement of parental awareness, bedside immunizations of newborns, coordination between immunization staff and maternal health staff, better communication, and clear definition of responsibility in the immunization service delivery will help achieve the goals of vaccinating newborns.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine preventable deaths and the Global Immunization Vision and Strategy, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:511–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ophori EA, Tula MY, Azih AV, Okojie R, Ikpo PE. Current trends of immunization in Nigeria: Prospect and challenges. Trop Med Health. 2014;42:67–75. doi: 10.2149/tmh.2013-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathew JL. Evidence-based options to improve routine immunization. Vaccine. 2009;95:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lahariya C. A brief history of vaccines & vaccination in India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:491–511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taneja G, Mentey VK, Jain M, Sagar KS, Tripathi B, Favin M, et al. Institutionalizing early vaccination of newborns delivered at government health facilities: Experiences from India. Int J Med Res Rev. 2015;3:521–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souter J. Vaccines given at birth. Prof Nurs Today. 2011;16:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trunz BB, Fine P, Dye C. Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: A meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness. Lancet. 2006;367:1173–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Universal Immunization Program – Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 19]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/1892s/5628564789562315.pdf .

- 9.Geeta MG, Riyaz A. Prevention of mother to child transmission of hepatitis B infection. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:189–92. doi: 10.1007/s13312-013-0062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navabakhsh B, Mehrabi N, Estakhri A, Mohamadnejad M, Poustchi H. Hepatitis B virus infection during pregnancy: Transmission and prevention. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2011;3:92–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morantz CA. Practice guidelines: ACIP updates recommendations for prevention of hepatitisatitis B virus transmission. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:1839–47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. Hepatitisatitis B. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 19]. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/HepatitisatitisB/en/

- 13.Immunization Handbook for Medical Officers. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2008. Department of Health and Family Welfare; pp. 31–2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta V, Mohapatra D, Kumar V. Assessment of vaccine wastage in a tertiary care centre of district Rohtak, Haryana. Natl J Community Med. 2015;6:292–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lala MK, Lala KR. Thermostability of vaccines. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40:311–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta S, Umrigar P, Patel P, Bansal RK. Evaluation of vaccine wastage in Surat. Natl J Community Med. 2013;4:15–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta A, Holla RG, Gupta R, Devgan A. Daily immunization services: A moral duty, not an empty slogan. Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68:399–402. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downing SG, Lagani W, Guy R, Hellard M. Barriers to the delivery of the hepatitis B birth dose: A study of five Papua New Guinean hospitals in 2007. P N G Med J. 2008;51:47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobel HL, Mantaring JB, 3rd, Cuevas F, Ducusin JV, Thorley M, Hennessey KA, et al. Implementing a national policy for hepatitis B birth dose vaccination in Philippines: Lessons for improved delivery. Vaccine. 2011;29:941–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuruvilla TA, Bridgitte A. Timing of zero dose of OPV, first dose of hepatitis B and BCG vaccines. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:1013–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinnakali P, Kulkarni V, Kalaiselvi S, Nongkynrih B. Vaccine wastage assessment in a primary care setting in urban India. J Pediatr Sci. 2012;4:e119. [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO. Projected Vaccine Wastage. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 19]. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/immunization.delivery/systems...projected_wastage/en/index.html .

- 23.Parmar DR, PatiL SW, Golawar SH. Assessment of vaccine wastage in tertiary care centre of district Nagpur, Maharashtra. Indian J Appl Res. 2016;6:133–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukherjee A, Ahiuwalia TP, Gaur LN, Mittal R, Kambo L, Saxena NC, et al. Assessment of vaccine wastage during a pulse polio immunization programme in India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2004;22:13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]