Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Although acne vulgaris is common in adolescents, information on their understanding of acne is minimal.

OBJECTIVES:

To evaluate the perceptions and beliefs of Saudi youth on acne.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Three hundred twenty-nine male students (aged 13–22 years) from 6 secondary schools in the Eastern Saudi Arabia completed a self-reported questionnaire on knowledge, causation, exacerbating and relieving factors of acne. Data were analyzed by SPSS version 15.0. Results of subjects with acne, a family history of acne, and parents' educational levels were compared. Differences between the analyzed groups were assessed by a Chi-square test; p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS:

Over half (58.9%) of the participants considered acne a transient condition not requiring therapy. Only 13.1% knew that the proper treatment of acne could take a long time, even several years. Over half (52%) thought acne can be treated from the first or after few visits to the doctor. Popular sources of information were television/radio (47.7%), friends (45.6%), and the internet (38%). Only 23.4% indicated school as a source of knowledge. Reported causal factors included scratching (88.5%) and squeezing (82.1%) of pimples, poor hygiene (83.9%), poor dietary habits (71.5%), and stress (54.1%). Ameliorating factors included frequent washing of the face (52.9%), exercise (41.1%), sunbathing (24.1%), and drinking of mineral water (21%). The correlations of these facts are discussed.

CONCLUSION:

Results of this study point out that misconceptions of acne are widespread among Saudi youth. A health education program is needed to improve the understanding of the condition.

Key words: Acne, perceptions, Saudi, male, youth

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a common condition extremely prevalent among teenagers and young adults under the age of 24 years. Nearly 85% of adolescents in this age group experience some degree of acne.[1,2,3]

Acne lasts for several years and thus may significantly influence in many ways the lives of those affected. For many teens, the disease could create cosmetic, physical, and psychological scarring fueling anxiety, depression, and other emotional trauma that threaten their quality of life.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10] Therefore, early and effective treatment is needed to save these patients from all the possible complications. Successful treatment of acne is significantly affected by the level of knowledge of the patients.[11,12,13,14,15] The present study was conducted to evaluate the level of knowledge of acne and the factors which could impact the course of the disease in male Saudi youth.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted among young male students from six secondary schools in Eastern Saudi Arabia. A total of 329 male youths (aged 13–22 years) were included in this study. All participants completed a specially prepared questionnaire which included demographic data as well as questions on their knowledge about acne and the factors influencing the disease. The questionnaire was compiled in Arabic and structured with slight modifications from questions used in previous publications.[13,16,17] The questionnaire was distributed to the adolescents and collected by the teachers and the investigator after completion. The questionnaire was anonymous and participation was voluntary. A 100% response rate was obtained.

Data were analyzed using the (SPSS software version 15.0 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA, 2008). The perceptions of participants was compared by having acne, family history of acne, and mother's and father's education level. Differences between the analyzed groups were assessed by Chi-square test, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

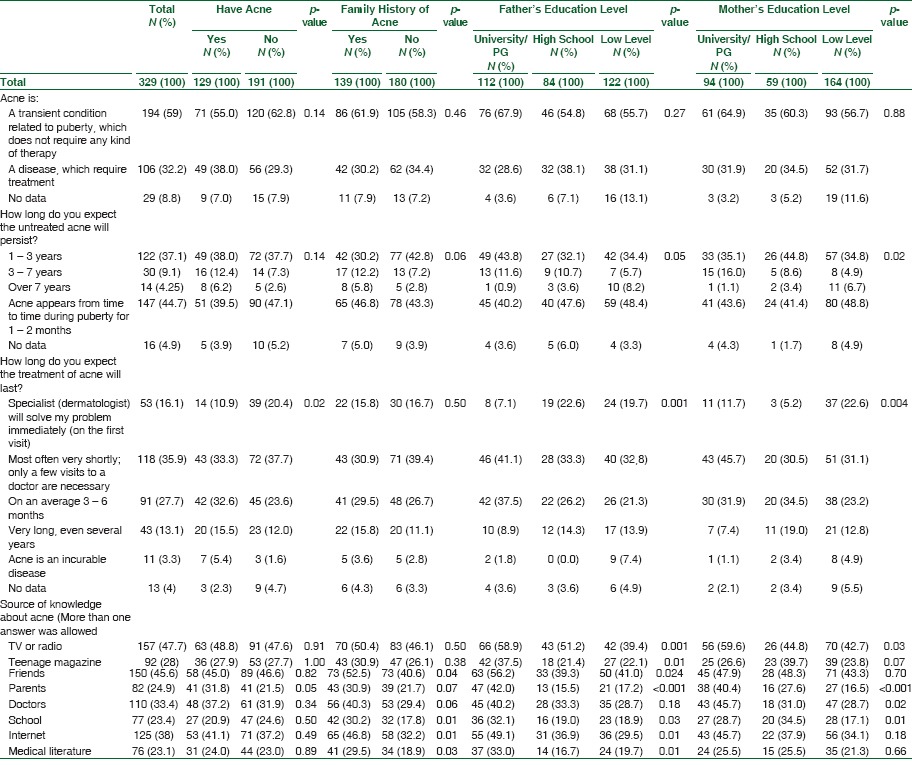

One hundred and twenty-nine (39.2%) of the subjects self-reported acne vulgaris. In 139 (42.3%) of the study population, there was a family history of acne. Over half of the participants (58.9%) considered acne a transient condition that did not require treatment. There were no significant differences in the frequency of this belief between respondents with and without self-reported acne. The same results were seen in participants with and without a family history of acne and regardless of the parents' educational level (P > 0.05) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Knowledge about Acne Vulgaris among Saudi Male Youths by have acne, family history of acne, and father and mother education

In addition, 44.7% students believed that acne appears from time to time during puberty for only 1 or 2 months. About 37% hundred and twenty-two (37.1%) thought that untreated acne lasted only 1–3 years. There were no statistically significant differences observed by having acne and a family history of acne [Table 1].

Regarding the duration of treatment, over half (52%) of the subjects believed that the treatment was short-term and needed only one or a few visits to the doctor. Only 13.1% knew that the proper treatment of acne could take a very long time, even several years. Moreover, the belief that acne was transient and could be treated on the first visit to the doctor was more frequently observed in those without acne than those with the disease (58.1% vs. 44.2%; P < 0.05). The family history of acne did not significantly influence this aspect of knowledge.

The sources of knowledge about acne were television/radio (47.7%), followed by friends (45.6%), internet (38%), doctor (33.4%), and magazines for teenagers (28%); 23.4% reported that school was the source of information on acne. Having acne did not significantly influence the sources of information about the condition [Table 1]. However, subjects without a family history of acne more frequently obtained information on the condition from friends (52.5% vs. 40.6%; P < 0.05), school (30.2% vs. 17.8%; P < 0.05), the internet (46.8% vs. 32.2%; P < 0.05), and medical literature (29.5% vs. 18.9%; P < 0.05).

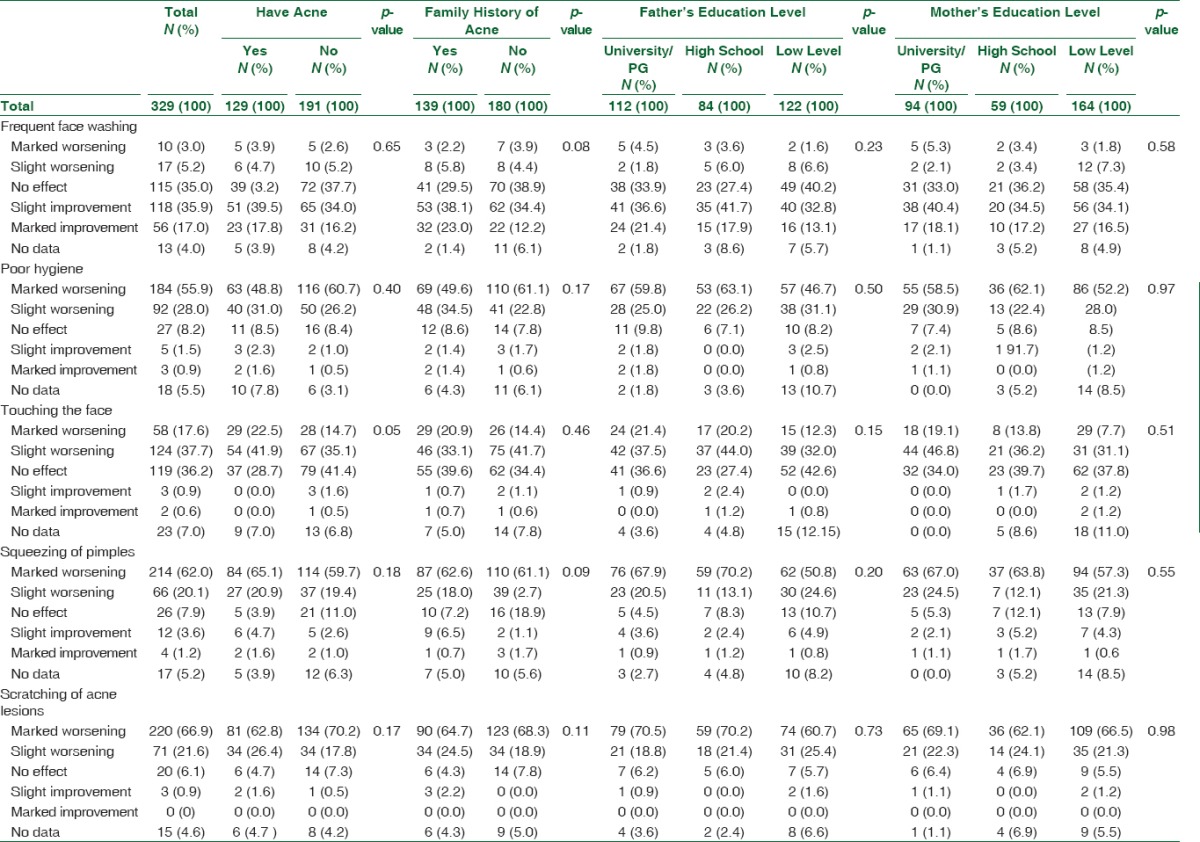

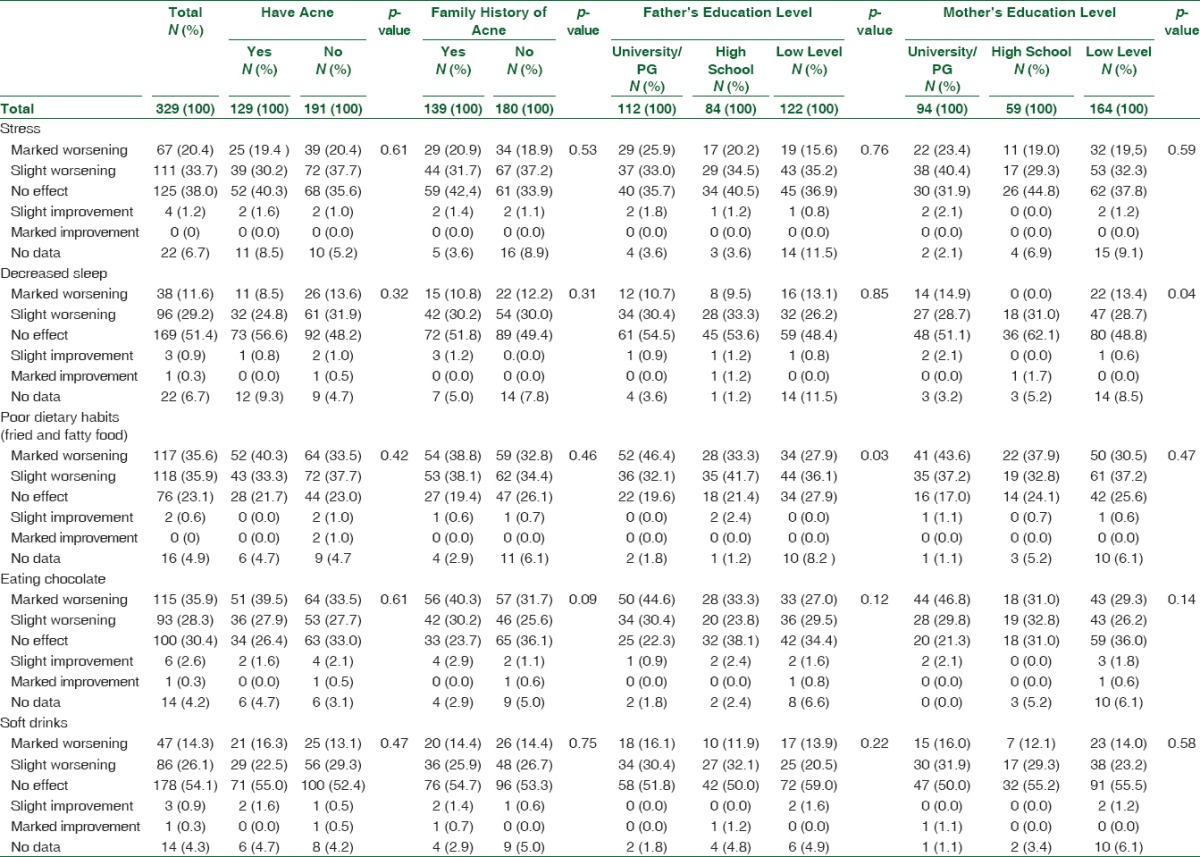

Regarding knowledge of factors influencing acne, the most frequently reported exacerbating factors in a descending order included scratching (88.5%) and squeezing of pimples (82.1%), poor hygiene (83.9%), poor dietary habits (71.5%), chocolate (64.2%), touching of face (55.3%), and stress (54.1%). Other factors considered by subjects as responsible for exacerbating acne included not having enough sleep (40.8%) and drinking soft drinks (40.4%) [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Knowledge about the influence of hygiene and skin care on acne lesions among Saudi Male Youths by have acne, family history of acne, and father and mother education

Table 3.

Knowledge about the influence of diet, stress, and sleep on acne lesions among Saudi Male Youths by have acne, family history of acne, and father and mother education

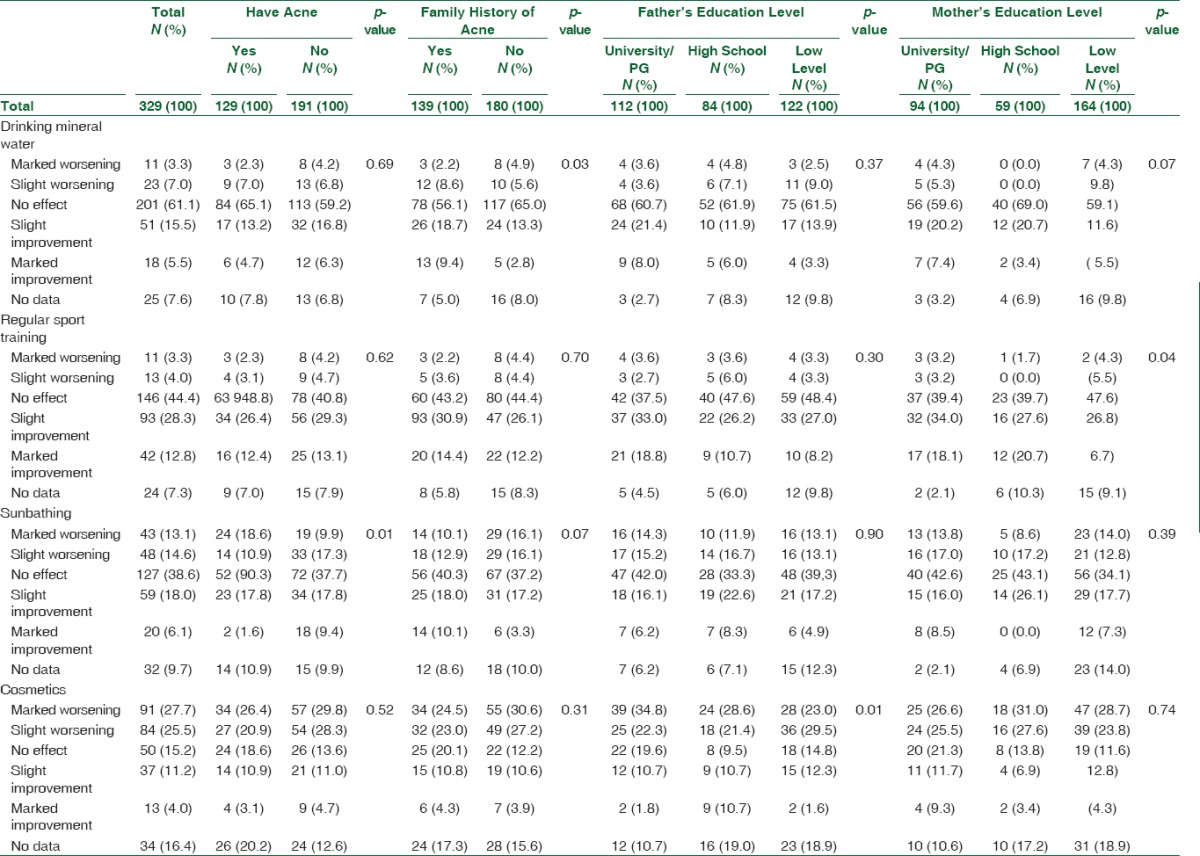

Ameliorating factors included frequent face washing (52.9%), regular exercise (41.1%), sunbathing (24.1%), and drinking mineral water (21%) [Tables 2 and 4]. A comparison of the participants with and without acne showed that those without acne indicated that sunbathing more frequently may slightly or markedly improve acne lesions (19.4% vs. 26.2%; P = 0.01). In addition, participants with a positive history of acne compared to those with no family history of acne more frequently indicated that drinking mineral water improved the course of acne (28.1 vs. 16.1%; P = 0.03). Participants with no family history of acne more frequently believed that drinking mineral water had no effect on acne (65% vs. 56.1%; P = 0.03) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Knowledge about the influence of drinking water, exercise, sunbathing, and cosmetics on acne lesions among Saudi Male Youths by have acne, family history of acne, and father and mother education

Participants with fathers with higher education (university) more than those whose fathers had a little education (78.5% vs. 54%; P = 0.03) indicated that poor dietary habits markedly or slightly worsened acne [Table 3]. In addition, participants whose fathers had a higher level of education more frequently than those whose fathers had little education thought that cosmetics could worsen acne (57.1% vs. 52.5%; P = 0.01).

On the other hand, participants whose mothers had high school education or above more than those with less education thought that decreased sleep worsened acne (74.6% vs. 42.1%; P = 0.04) [Table 3]. In addition, respondents whose mothers had higher education indicated more frequently than those whose mothers were less educated that regular sports improved acne (52.1% vs. 48.3% vs. 33.5%; P = 0.04) [Table 4].

Discussion

Acne is an extremely common condition in adolescence, yet the literature that addresses knowledge of the condition in this age group is quite limited.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]

Misinformation and misconceptions about the disease prevail among the youth, the largest population affected by acne. The results of the current study are in agreement with those of previously published data that conclude that the knowledge level about acne is quite low, inadequate, and at times, erroneous. These perceptions regarding the disease are shared by pupils with and without acne in the population under study and even by patients, the general population, and health personnel in other populations of both the West and the East.[12,13,14,16,17,18,22,24]

When asked about the source of information on acne, the teenagers most commonly indicated the mass media (television, radio, internet, teenage magazines) and then friends, doctors, and parents. Other studies have also reported the mass media as a popular source of information for teenagers.[10,13,25] Similarly, Al Robaee reported that the most common source of information for university students in Central Saudi Arabia was the newspapers (35.6%) and television (26.3%). Other sources included physicians (12.3%) and schools (12.1%). Unexpectedly, in an age when peer influence is supposedly quite high, the role of friends as the source of information was minimal and accounted for only 8.1%. Parents did not contribute to education in this group.[26] In contrast to the reports of the current study and Al Robaee's, a report from the Asir region of Saudi Arabia indicated that doctors were the most common source of information to patients.[21] Similarly, Al-Hoqail's report pointed out that misconceptions and misguided ideas of Saudi students in the Riyadh region were widespread; however, it did not mention the sources of information of the studied groups.[20] In Turkey, students' sources of information on acne were doctors (35%), the internet (28.3%), friends (19.1%), and pharmacists (14%).[27] However, the majority of Lithuanian school children got their information on acne from their parents (76.3%), magazines (35.5%), and friends (29.3%).[28] In the current study, only 23.4% indicated school as a source of information. Therefore, directed education on acne should use the mass media for the effective delivery of information on acne to adolescents. However, since schools are responsible for the education of adolescents, the acquisition of their knowledge and insight into the acne should be scrutinized and the level of their awareness raised through educational programs given in schools.

About one-third of the participants stated that they got their information on acne from doctors, many of whom were family physicians or general practitioners. This is similar to the study of European youth with acne in which 27% reportedly got their information on the condition from either general practitioners or dermatologists and less often from the internet or family members.[29] This observation was also documented in a previous study by Brajac et al.[16] that stated that many family physicians were themselves misinformed about acne, which often led to the inadequate treatment of patients. They suggested that there should be programs to inform family physicians since they are the main providers of care for patients' acne vulgaris in many communities and countries.

In this study, about 52% of the participants believed that acne was short-lived and could be cured quickly or only after a few visits to the doctor in contrast to the 20% reported by Reich et al.[13] Su et al. reported that 10% of Singaporean youths thought acne would disappear in adulthood and another 3.7% thought the condition was incurable.[30] Other authors similarly demonstrated that many of their participants believed that treatment would significantly improve their acne within 4–6 weeks.[12,16,22,23,31]

The previous studies carried out on Saudi students are in agreement with the results of the current study. Al-Hoqail[20] reported that 62% of the youths believed acne was not a serious problem while 56.7% considered the condition both a cosmetic and a health problem. Al-Robaee[26] reported that 85.4% thought acne was an acute treatable disease that required short-term treatment in 74% of cases, while 13.2% thought it was a serious disease. On the other hand, Al Mashat et al. reported that in their study population, 63.3% thought acne was a curable disease while 53.8% thought it was a serious problem.[32] Darwish and Al-Rubaya reported that 47% of their respondents believed acne needed long-term treatment by doctors with a guaranteed outcome in 87.2%.[33]

Contrary to other investigators who did not find any statistically significant difference between participants with and without acne regarding the treatment of acne,[13,18] in this study, the false belief that acne was transient and could be treated after the first visit or after a few visits to the doctor was more frequently observed in those without acne than those with acne. This misconception could lead to premature discontinuation of the treatment and poor compliance. Therefore, patients should be educated and informed that long-term treatment is needed for efficient control of the condition.

Even though genetics, hormones, and infection have been proven to play a role in the pathogenesis of acne, there is very little evidence on whether such factors as dietary restriction, facial hygiene, and sunlight exposure, positively or negatively influenced acne and its management. Although still unproven and controversial,[2,34] the perception that diet is a cause or aggravating factor of acne is a strongly held belief among adolescents and participants with acne worldwide.[9,10,13,14,18,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,28,30,35,36,37,38]

The number of studies that have examined the role of diet in acne over the past four decades is still quite small; however, there is growing evidence to suggest a possible relationship.[39,40] More research is now focused on the role of dietary glycemic load suggesting that high glycemic load diets, the consumption of milk, saturated fat, and trans fat may influence or aggravate acne.[41,42,43]

More than 71.5% of all respondents of this study cited diet as the most frequent aggravating factor of acne, a figure higher than that reported by other studies.[12,18,22,25,36] In comparison to the previous studies conducted on Saudi youths, the author's figure is akin to that of Al-Hoqail[20] who also found diet (72.1%) the most frequently named cause or aggravating factor of acne by Saudi youth in the Central region, and that of Tallab[21] among students in Asir region. Similarly, Darwish and Al-Rubaya reported food as either a cause or an aggravating factor in the majority of their study group in Eastern Saudi Arabia, with chocolate, fatty food, and snacks accounting for 79.4%, 53.9%, and 53.9%, respectively.[33] However, Al Robaee's study reported that only 19.4% of Saudi youths in Central Riyadh mentioned the role of diet in acne.[26] Al Mashat et al., on the other hand, indicated that in the study population in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 28.4% cited diet as a cause and 34.1% as an aggravating factor.[32] The higher percentages found in the majority of Saudi male youth in this study could be explained by the proliferation of fast food chains in Saudi Arabia over the past decade and a half, with more and more teens changing to a more Westernized diet. Among the notoriously reported exacerbating dietary factors reported, fatty foods (71.5%) were believed to be the most common followed by chocolates (64.2%) and the consumption of carbonated soft drinks (40.4%), which is in agreement with the findings from other studies.[9,13,22,25,35]

Poor hygiene was thought to be a cause or an aggravating factor of acne by the majority (83.9%) of respondents in this study. The misconception that acne is associated with poor hygiene and insufficient cleansing of the face appears to be common in Saudi,[20,21,26,32] Asian,[30,38] European youths,[28,29,44] and worldwide. Smithard et al.[18] reported that <1/3 of participants with acne actually sought medical advice and that the majority of the teenagers washed their faces more frequently in an attempt to control their acne. In a beauty conscious society which puts pressure on vulnerable adolescents, there seems to be an unrealistic urge to have flawless skin, especially in those who suffer from acne driving them to use over-the-counter products, cleansers, nonmedical and facial treatments from beauty salons without medical advice, or quite in advance of consulting a physician or dermatologist.[27,28,29,30,44]

In a recent study evaluating the perceptions of 786 Italian patients on the role of cleansers in acne, Veraldi et al. found that 70% of the patients used a specific anti-acne cleanser in the treatment of their condition either alone or as an adjuvant, and 66% of the respondents believed that the cleanser had a therapeutic role.[44] Similarly, Lithuanian school children pointed out poor hygiene (69%) as the main causal or exacerbating factor of acne.[28] Karciauskiene et al. found that the majority of these youths (84.9%) with acne had been using cosmetic remedies to control their acne thinking that their acne was caused by unhygienic practices. Only 7% of the pupils received treatment from a dermatologist.[28]

There is still no convincing evidence to show the positive effect of exposure to sunlight on acne. The results of studies from Poland and Saudi Arabia cite a positive effect[13,45] while others from Nigeria, Greece, Singapore, Jordan, and Thailand cite a causal or exacerbation effect.[9,10,30,35,38] About a quarter (24.1%) of the Saudi youth cited a positive effect; 27.7% cited a worsening effect and over a third (38.6%) believed sunlight had no effect on acne.

In the present study, 54% of the respondents believed that stress played a role in aggravating acne, compared to the higher figures ranging from 67% to 76% reported by Rasmussen and Smith, Al-Hoqail, and Green and Sinclair.[12,20,36] Lower percentages have been reported by several other authors.[9,10,13,21,35]

Other factors thought to be responsible for exacerbating acne in this study group included the squeezing and scratching of the pimple, cosmetics, and decreased sleep. These perceptions were no different from the ones reported by other authors.[9,10,13,22,35] The opinions and perceptions of Asian youth were incredibly similar to those of the Saudi youth, particularly with respect to the perceptions on aggravating factors of acne. More than half believed that inadequate sleep, stress, sweat/exercise/hot weather, sun exposure, cosmetics, and oily foods aggravated their acne.[38] This can be explained by the similarity in cultural, environmental conditions and dietary habits.

Limitations of the study are the missing data analysis and some incorrectly answered questions. The number of published randomized controlled trials serving as a scientific base is quite limited. Nevertheless, despite the smallness of the sample size of most studies in the literature and the fact that they are often uncontrolled or unblended, reports on adolescents' perceptions and knowledge on acne are important in providing some insight into how dermatologists or other care providers can improve patient education and management. Educating teenagers on factors that either negatively or positively affect the course of acne is essential. The evidence base for recommendations is still inadequate, so more research is needed.

Conclusion

The data from this study of Saudi youths support the findings of other studies that indicate that adolescents' general knowledge about acne is meager and often erroneous. Educational programs should be directed at this age group in schools and the mass media. Young people should be made aware that acne is a disease that can be managed and controlled effectively. Better knowledge and awareness as to which factors positively or negatively influence acne will improve compliance to the treatment regimen and efficacy of results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Khulood Al-Nutaifi and Dr. Fahad Al-Ajmi who assisted in the distribution of the questionnaires.

References

- 1.Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galobardes B, Davey Smith G, Jefferys M, McCarron P. Glasgow Alumni Cohort. Has acne increased? Prevalence of acne history among university students between 1948 and 1968. The Glasgow Alumni Cohort Study. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:824–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergfeld WF. The evaluation and management of acne: Economic considerations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(5 Pt 3):S52–6. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bez Y, Yesilova Y, Ari M, Kaya MC, Alpak G, Bulut M. Predictive value of obsessive compulsive symptoms involving the skin on quality of life in patients with acne vulgaris. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:679–83. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timms RM. Moderate acne as a potential barrier to social relationships: Myth or reality? Psychol Health Med. 2013;18:310–20. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.726363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Evaluation of cutaneous body image dissatisfaction in the dermatology patient. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magin P. Appearance-related bullying and skin disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritvo E, Del Rosso JQ, Stillman MA, La Riche C. Psychosocial judgements and perceptions of adolescents with acne vulgaris: A blinded, controlled comparison of adult and peer evaluations. Biopsychosoc Med. 2011;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yahya H. Acne vulgaris in Nigerian adolescents – Prevalence, severity, beliefs, perceptions, and practices. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:498–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Ifandi A, Efstathiou G, Georgala S, Chalkias J, et al. Coping with acne: Beliefs and perceptions in a sample of secondary school Greek pupils. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:806–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsambas AD. Why and when the treatment of acne fails. What to do. Dermatology. 1998;196:158–61. doi: 10.1159/000017851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasmussen JE, Smith SB. Patient concepts and misconceptions about acne. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:570–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reich A, Jasiuk B, Samotij D, Tracinska A, Trybucka K, Szepietowski JC. Acne vulgaris: What teenagers think about it. Dermatol Nurs. 2007;19:49–54, 64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poli F, Auffret N, Beylot C, Chivot M, Faure M, Moyse D, et al. Acne as seen by adolescents: Results of questionnaire study in 852 French individuals. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:531–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan HH, Tan AW, Barkham T, Yan XY, Zhu M. Community-based study of acne vulgaris in adolescents in Singapore. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:547–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brajac I, Bilic-Zulle L, Tkalcic M, Loncarek K, Gruber F. Acne vulgaris: Myths and misconceptions among patients and family physicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;54:21–5. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00168-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimball A, Choi J. An assessement of acne myth belief in college students. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smithard A, Glazebrook C, Williams HC. Acne prevalence, knowledge about acne and psychological morbidity in mid-adolescence: A community-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:274–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lello J, Pearl A, Arroll B, Yallop J, Birchall NM. Prevalence of acne vulgaris in Auckland senior high school students. N Z Med J. 1995;108:287–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Hoqail IA. Knowledge, beliefs and perception of youth toward acne vulgaris. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:765–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tallab TM. Beliefs, perceptions and psychological impact of acne vulgaris among patients in the Assir region of Saudi Arabia. West Afr J Med. 2004;23:85–7. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v23i1.28092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uslu G, Sendur N, Uslu M, Savk E, Karaman G, Eskin M. Acne: Prevalence, perceptions and effects on psychological health among adolescents in Aydin, Turkey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:462–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan JK, Vasey K, Fung KY. Beliefs and perceptions of patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:439–45. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.111340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearl A, Arroll B, Lello J, Birchall NM. The impact of acne: A study of adolescents' attitudes, perception and knowledge. N Z Med J. 1998;111:269–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali G, Mehtab K, Sheikh ZA, Ali HG, Abdel Kader S, Mansoor H, et al. Beliefs and perceptions of acne among a sample of students from Sindh Medical College, Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al Robaee AA. Prevalence, knowledge, beliefs and psychosocial impact of acne in University students in Central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:1958–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gokdemir G, Fisek N, Köslü A, Kutlubay Z. Beliefs, perceptions and sociological impact of patients with acne vulgaris in the Turkish population. J Dermatol. 2011;38:504–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karciauskiene J, Valiukeviciene S, Stang A, Gollnick H. Beliefs, perceptions, and treatment modalities of acne among schoolchildren in Lithuania: A cross-sectional study. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:e70–8. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delarue A, Zkik A, Berdeaux G. Characteristics of acne vulgaris in European adolescents and patients perceptions. Value Health. 2015;18:A425. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su P, Chen Wee Aw D, Lee SH, Han Sim Toh MP. Beliefs, perceptions and psychosocial impact of acne amongst Singaporean students in tertiary institutions. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:227–33. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McEvoy B, Nydegger R, Williams G. Factors related to patient compliance in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:274–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al Mashat S, Al Sharif N, Zimmo S. Acne awareness and perception among population in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. JSSDDS. 2013;17:47–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darwish MA, Al-Rubaya AA. Knowledge, beliefs, and psychosocial effect of acne vulgaris among Saudi acne patients. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:929340. doi: 10.1155/2013/929340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thiboutot DM, Strauss JS. Diet and acne revisited. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1591–2. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.12.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Akawi Z, Abdel-Latif Nemr N, Abdul-Razzak K, Al-Aboosi M. Factors believed by Jordanian acne patients to affect their acne condition. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12:840–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green J, Sinclair RD. Perceptions of acne vulgaris in final year medical student written examination answers. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:98–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, Hill K, Eaton SB, Brand-Miller J. Acne vulgaris: A disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1584–90. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.12.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suthipinittharm P, Noppakun N, Kulthanan K, Jiamton S, Rajatanavin N, Aunhachoke K, et al. Opinions and perceptions on acne: A community-based questionnaire study in Thai students. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96:952–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K. Acne: The role of medical nutrition therapy. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:416–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Danby FW, Frazier AL, Willett WC, Holmes MD. High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ismail NH, Manaf ZA, Azizan NZ. High glycemic load diet, milk and ice cream consumption are related to acne vulgaris in Malaysian young adults: A case control study. BMC Dermatol. 2012;12:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-12-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K. Relationships of self-reported dietary factors and perceived acne severity in a cohort of New York young adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:384–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, Danby FW, Rockett HH, Colditz GA, et al. Milk consumption and acne in teenaged boys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:787–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veraldi S, Barbareschi M, Micali G, Skroza N, Guanziroli E, Schianchi R, et al. Role of cleansers in the management of acne: Results of an Italian survey in 786 patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:439–42. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1133880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Ameer AM, Al-Akloby OM. Demographic features and seasonal variations in patients with acne vulgaris in Saudi Arabia: A hospital-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:870–1. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]